Abstract

In the new millennium, there has been a huge surge in the numbers of procedures performed under sedation in pediatric patients outside the operating room. Traditionally, these were performed by anesthesiologists. Increasingly, other specialists, such as emergency room physicians, pediatricians and radiologists, are involved in the management of procedural sedations under elective or emergency situations. Professional organizations such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and other organizations are working continuously to make procedural sedation for children safe, economical and tailored to the needs of the child and the diagnostic/therapeutic procedure being performed. Multi-institutional databases have been set up to investigate the complications related to procedural sedation and lessons are being learned from the analysis of these data. This article reviews these data and describes strategies to prevent and manage common adverse events following procedural sedation in children outside the operating room.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s) ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test and/or complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: May 4, 2011; Expiration date: May 4, 2012

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

• Describe general principles of pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room

• Describe common adverse events during pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room and their management

• Describe strategies to prevent adverse events and improve safety during pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti,Editorial Director, Future Science Group, London, UK

Disclosure:Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Laurie Barclay,Freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC

Disclosure:Laurie Barclay, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS

Ramesh Ramaiah, MD, FCARCSI, FRCA,Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington, WA, USA

Disclosure:Ramesh Ramaiah, MD, FCARCSI, FRCA, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Sanjay Bhananker, MD, FRCA,Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington, WA, USA

Disclosure:Sanjay Bhananker, MD, FRCA, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

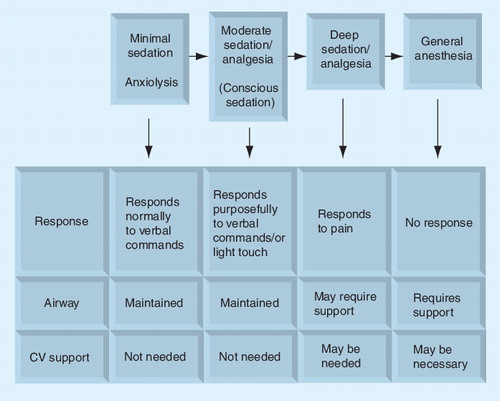

CV: Cardiovascular.

The number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures performed under sedation in pediatric patients outside the operating room setting has increased substantially over the past decade Citation[1,2]. Consequently, both anesthesiologists and nonanesthesiologists are striving to provide safe and effective sedation and analgesia to these children. The primary aim of procedural sedation is to provide anxiolysis, analgesia and control of movement during painful or unpleasant procedures. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has mandated that anesthesiologists be responsible for developing institutional guidelines for pediatric sedation practice Citation[3]. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published guidelines for sedation administered by nonanesthesiologists that have been endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Citation[1,3–5]. The pharmacological agents used, depth of sedation provided, monitoring modalities used and degree of training of sedation providers varies greatly from one institute to another. As a result, sedation of pediatric patients outside the operating room setting is not well standardized across institutions. This article addresses strategies to prevent and manage common adverse events during pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room.

Incidence & nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation & analgesia

One of the most important aspects of pediatric sedation and analgesia is to optimize patient safety by minimizing complications. Adverse events during sedation in children can occur owing to a variety of reasons, such as drug overdose, inadequate monitoring, drug errors, inadequate skills of the personnel administering drugs and premature discharge Citation[6]. In total, 80% of the complications during sedation and analgesia are secondary to adverse airway/respiratory events Citation[7,8]. The majority of these complications can be managed with simple maneuvers, such as providing supplemental oxygen, opening the airway, suctioning and using bag–mask–valve ventilation. Occasionally, a more advanced airway management, such as endotracheal intubation or use of a laryngeal mask airway, is required for ventilatory assistance.

One study reviewed contributing factors associated with adverse events during pediatric sedation using event information from the US FDA adverse event self-reporting system – the US Pharmacopoeia Report of Adverse Events – and results of a survey of more than 1000 pediatric specialists Citation[7]. Of the 118 case reports, 95 incidents from both hospitals and nonhospital settings were reviewed. Outcomes included death (n = 51), neurological injury (n = 9), prolonged hospital stay (n = 21) and no harm (n = 14). The majority (80%) of adverse events were airway/respiratory in origin in both the hospital and nonhospital settings. Other causes of adverse events included drug interaction/overdose, inadequate monitoring, inadequate initial health evaluation, lack of independent observer and inadequate management of resuscitation. There was no relationship between negative outcome and the route of drug administration. Surprisingly, large percentages of patients in this study were not monitored by pulse oximetry, despite its wide availability in both hospital and nonhospital settings; the use of pulse oximetry was associated with a better outcome.

A recent study reported that 8.6% of children were agitated during procedural sedation Citation[9]. Among these agitated children, the majority had nonserious adverse events, such as failure to sedate adequately, waking up before the end of procedure and so on. However, serious adverse events, such as cardiovascular collapse needing resuscitation and allergic reactions, were rare.

Two large database studies have been published in the last 2 years, both of them from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium – a collaborative group of 37 institutions in North America who share information on pediatric sedation practice. The first study, published in 2006, evaluated the incidence and nature of adverse events among 30,000 sedation encounters in 26 institutions for procedures outside the operating room Citation[10]. All of the participating institutions had a dedicated sedation team including anesthesiologists, emergency medicine physicians, internists or hospitalists. They reported that there was no incidence of death, one cardiac arrest (directly associated with sedation care) and one aspiration episode. However, one in 400 procedures was associated with stridor, laryngospasm, wheezing or apnea that could progress to poor outcome if they were not managed appropriately. One in every 200 sedations required airway and ventilation interventions, such as bag–mask ventilation, oral airway placement or emergency intubation. The low incidence of serious adverse events in this study could be due to the fact that the institutions in this study outperform some of the pediatric sedation programs that operate without policy guidelines or stringent quality improvement processes.

A more recent publication by the same pediatric sedation research consortium describes the findings from 49,836 sedation encounters involving propofol as a sedative medication by the same array of specialists mentioned in the earlier study Citation[11,12]. They reported two cardiac arrests, four aspiration events and no deaths among this cohort. One in 65 of these sedation/anesthesia encounters was associated with stridor, laryngospasm, airway obstruction, wheezing or central apnea. The authors concluded that both studies do not simply reassure the providers that the sedation in children is low risk; rather it reflects the performance among highly selected and motivated sedation groups Citation[12].

The major goals of pediatric procedural sedation may vary with the specific procedure, but they generally encompass relief of anxiety, pain control and control of excessive movement. The failure rate to achieve these goals has been reported by various authors to be from as infrequent as 1–3% Citation[13,14], to as frequent as 10–20% Citation[6,15,16].

The concept of the continuum of the sedation spectrum

The first guidelines for pediatric sedation were published in 1985 in response to the reports of three deaths in a single dental office primarily involving dental sedation Citation[17,18]. The guidelines were written with the cooperation of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and the ASA. The main focus of these guidelines was to address the system issues, such as the need for informed consent and fasting before sedation, frequent measurement and documentation of vital signs, the availability of age-appropriate equipment, the use of physiologic monitoring, the need for basic life support skills and proper recovery and discharge procedures. These original guidelines defined three levels of depth of sedation: conscious sedation, deep sedation and general anesthesia. Conscious sedation was defined as a minimally depressed level of consciousness that retains the patient’s ability to maintain a patent airway independently and continuously, and respond appropriately to physical stimulation and/or verbal command, for example, ‘open your eyes’. The choice of this terminology led to confusion, as conscious sedation is rarely attained in children. In 1992, the AAP Committee on Drugs revised the 1985 guidelines Citation[19]. They stated that regardless of the intended level of sedation or route of administration, a patient could progress from one level of sedation to another and that the provider must have the skills and equipment necessary to safely manage patients who have progressed to a deeper level of sedation. Pulse oximetry was recommended for all patients undergoing sedation. This new guideline also discouraged the practice of parents administering sedation at home. An amendment to this guideline was published by the AAP Committee on Drugs in 2002 Citation[5]. It eliminated the use of the term conscious sedation. The current guidelines use the terminology of minimal sedation, moderate sedation, deep sedation and general anesthesia to describe the continuum of the sedation spectrum .

This terminology is consistent with that used by the ASA and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. This amendment reaffirms the following principles for the sedation of pediatric patients:

• The patient must undergo a documented pre-sedation medical evaluation, including a focused airway exam;

• There should be an appropriate interval of fasting before sedation;

• Children should not receive sedative or anxiolytic medications without supervision from skilled medical personnel (i.e., medication should not be administered at home or by a technician without medical supervision);

• Sedative and anxiolytic medications should only be administered by, or in the presence of, individuals skilled in airway management and cardiopulmonary resuscitation;

• Age- and size-appropriate equipment and appropriate medications to sustain life should be checked before sedation, and be immediately available;

• All patients sedated for a procedure must be continuously monitored with pulse oximetry;

• An individual must be specifically assigned to monitor the patient’s cardiorespiratory status during and after the procedure; for deeply sedated patients, that individual should have no other responsibilities and should record vital signs at least every 5 min;

• Specific discharge criteria must be used. The guidelines for the monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation apply, regardless of the setting in which sedatives are administered or the specific training or profession of the practitioners involved. Children sedated using medication with a long half-life (e.g., chloral hydrate, pentobarbital and chlorpromazine) may require extended observation.

It is vital to remember that the patient may rapidly move from one level of sedation to another (e.g., a child can move from deep sedation to either moderate sedation or to a state of general anesthesia) and, hence, personnel should have the training, in addition to the equipment, to rescue the child from deeper levels of sedation at all times when procedural sedation is provided. There are some questions raised about the concept of the sedation continuum, as it relies on subjectivity in identifying and quantifying a patient’s response to verbal or tactile stimulation. This subjectivity may vary among observers and it is not logical to apply this to patients who may be unable to respond appropriately, for example, patients with hearing impairments, developmental delay, neurological compromise or at extremes of age. In the future, it may be possible to reformulate the sedation continuum by shifting away from subjective assessment to more objective vital signs monitoring, through focused research and the development of a multidisciplinary sedation community to help define the stages of sedation.

Following the implementation of the 2001 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations guidelines, the incidence of adverse events during procedural sedation has been markedly reduced Citation[20]. Adherence to AAP/ASA guidelines for pediatric procedural sedation may reduce the adverse events, and there is direct evidence that elements of the AAP/ASA structural model for procedural sedation could be adopted by nonanesthesiologists with an apparent risk reduction Citation[21].

Strategies to reduce the incidence of adverse events during procedural sedation

Preoperative health evaluation

Health evaluation before sedation should be performed by an appropriately licensed practitioner and reviewed by the sedation team at the time of treatment for possible interval changes. This provides an opportunity to identify specific risk factors, and may warrant additional consultation before sedation. Health evaluation will also screen out patients whose sedation will require more advanced airway or cardiovascular management skills or alteration in the doses or types of medications used for procedural sedation.

Preoperative evaluation should include:

• Obtaining age and weight;

• Obtaining health history, including allergies or adverse reactions, medication history, relevant diseases, physical abnormalities and neurological impairment that may increase the potential for airway obstruction (history of snoring or obstructive sleep apnea). The summary of previous relevant hospitalizations, including history of sedation or general anesthesia and any complications, should be obtained. Relevant family history, particularly that related to anesthesia, should also be included;

• Performing a review of systems with a special focus on abnormalities of cardiac, pulmonary, renal and hepatic function that might alter the child’s expected responses to sedation/analgesic medications;

• The recording and documenting of vital signs (for some children who are noncooperative, this may not be possible; however, this occurrence should be documented);

• A physical examination, including a focused evaluation of the airway (tonsillar hypertrophy, abnormal anatomy, e.g., mandibular hypoplasia) to determine whether there is increased risk of airway obstruction;

• Obtaining name, address and telephone number of the child’s medical guardian;

• A physical status evaluation (ASA classification) – patients who are ASA classes 1 and 2 are frequently considered appropriate candidates for minimal, moderate or deep sedation. Children of ASA classes 3 and 4, or those with special needs, require additional and individual considerations, particularly for moderate and deep sedation.

Pre-procedural fasting

The pre-procedural fasting guidelines, first published by the ASA in the 1980s, had the intention of reducing aspiration in anesthetized patients. These consensus-based guidelines were initially developed for patients who need general anesthesia, and have subsequently been extrapolated without adaptation to include all procedural sedation and analgesia Citation[22]. The literature suggests that the aspiration risk for procedural sedation and analgesia is lower than that of general anesthesia because the principal risk factors (airway manipulation, absence of protective airway reflexes and poor ASA physical status) are not present routinely in this setting Citation[23,24]. As a reflection of this evidence, some emergency physicians disregard preprocedural fasting guidelines. However, even though published studies suggest that strict adherence to the fasting guidelines is not necessary, their sample size and/or designs are insufficient to safely practice the liberalized preprocedural fasting guidelines and to justify changes in emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia policies.

Preparation & setup for sedation & analgesia

Adequate preparation, including selection of equipment, medication and monitors, is critical for the safe conduct of procedural sedation in children. A commonly used acronym that is useful in planning and preparation for a procedure is SOAPME .

Personnel & training

The provider responsible for sedation in pediatric patients must be familiar with monitoring, as per the AAP guidelines, and competent to manage the complications. The sedation may exceed the intended level, and the provider should be sufficiently skilled to rescue the child from a deeper level of sedation. The provider must be trained in and capable of providing bag–valve–mask ventilation and advanced airway skills if required, to keep the child oxygenated. At least one individual must be present who is trained in advanced pediatric life support. The human simulators offer an extremely promising technology in the promotion of safe administration of pediatric procedural sedation. This technology will train the sedation providers to recognize the critical airway emergencies and initiate resuscitation. The study, carried out to measure the system safety and errors supports, the feasibility of using available human simulation Citation[25].

Vascular access

Children receiving deep sedation should have an intravenous access placed at the start of the procedure. An intraosseous needle should be available in the event of failure to place an intravenous line, or if the intravenous line becomes nonfunctional in an emergency situation. If the child is receiving sedative agents other than via the intravenous route, for example, intranasal, oral or rectal, the need for intravenous access is debatable. Most authors recommend the placement of intravenous access for administration of emergency medications, including reversal agents, during procedural sedation.

During the procedure

Prior to administration of sedative medication, a baseline determination of vital signs should be documented. The selection of medication with appropriate concentration and labeling is essential in order to prevent medication errors Citation[7]. Medications with minimal effect on respiration are associated with fewer respiratory adverse events Citation[26], and titration of medication dose guided by bispectral index (BIS) may be useful in preventing oversedation Citation[27]. Commonly used pharmacological agents used for sedation in children and their adverse events are listed in . The provider should document the name, route, site and time of administration of all medications, along with their doses. Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation, heart rate and respiratory rate using capnography and intermittent measurement of blood pressure should be documented. The new-generation pulse oximeters are less susceptible to motion artifacts. The oximeters that change the tone with changes in hemoglobin saturation provide immediate aural warning to everyone within hearing distance. The oximeter probe must be properly positioned; clip-on devices can be easily displaced and could result in a false reading. Capnography is valuable in monitoring respiration, especially in children sedated in less accessible locations, such as during MRI, CT scan or in darkened rooms. Nasal cannulae that allow simultaneous delivery of oxygen and measurement of expired carbon dioxide are very useful in making the diagnosis of airway obstruction or apnea during sedation. In a recent randomized controlled trial, investigators have examined the use of capnography monitor during emergency department sedation using propofol and opioids in adults Citation[28]. They conclude that the addition of a capnography to standard monitoring reduces hypoxic events, and also provides early warning for the development of hypoxemia. Capnography has been demonstrated to improve patient safety during procedural sedation by reducing the apnea/hypoxia events Citation[29]. Any restraining devices should be checked to prevent airway obstruction or restriction of chest movement.

Adverse events & their management

Oxygenation & ventilation

Some of the potentially life-threatening adverse events associated with oxygenation and ventilation include oxygen desaturation, central apnea, airway obstruction (partial or complete), laryngospasm and clinically apparent pulmonary aspiration. The management of respiratory/airway adverse events includes one or more of the following interventions Citation[30]:

• Supplemental or increased inspired oxygen delivery;

• Vigorous tactile stimulation;

• Careful titration of reversal agents; nalaxone and flumezenil if respiratory depression is noted and positive pressure ventilation;

• Airway intervention, including shoulder roll, chin lift, jaw thrust and neck extension;

• Oral and pharyngeal suctioning;

• Placement of an oral or nasal airway;

• If laryngospasm is noted, initial treatment includes continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with 100% oxygen and airway manipulation (jaw thrust and chin lift) Citation[31]. If the initial interventions were unsuccessful, increase the depth of anesthesia with additional doses of sedative agents, and if necessary, administer small doses of succinylcholine to relax the vocal cords. Tracheal intubation should be considered if the laryngospasm remains refractory. Another technique that has been demonstrated to be effective in relieving laryngospasm is the application of bilateral digital pressure behind the ear lobes for a few seconds Citation[32];

• Placement of a laryngeal mask airway or endotracheal tube if other airway management is unsuccessful;

• If the patient has pulmonary aspiration, the child’s head should be placed on a lower level, and rapid suction of the airway and placement of an endotracheal tube should be carried out. Before the first ventilation, if the saturation is adequate, endotracheal suction should be performed to remove the stomach contents from the trachea and lower airway;

• Chest rigidity has been noted following the use of fentanyl. The management of chest rigidity includes positive pressure ventilation, and the use of muscle relaxants if the rigidity continues.

Cardiovascular adverse events

Bradycardia is defined as the pulse rate decreasing 2 standard deviations below normal for that age, and hypotension is defined as systolic blood pressure less than the fifth percentile for that age, as described by the American Heart Association (AHA) in the Pediatric Advanced Life Support provider manual. The management of adverse cardiovascular events includes maintaining oxygenation of the lungs and one or more of the following interventions: administration of intravenous fluids; chest compressions; and administration of medications, including atropine and epinephrine.

Excitatory movements, such as myoclonus, muscle rigidity & generalized motor seizures

These adverse events may interfere with the planned procedure, and need additional medication to control movements. Paradoxic response to sedation, including restlessness or agitation, may result in delay or discontinuation of the procedure. Unpleasant emergent reactions, including crying, agitation, delirium, nightmares and hallucinations, may be observed during recovery. Children with emergence reactions may be treated with administration of titrating doses of midazolam or diazepam.

Other rare complications during sedation and analgesia are permanent neurological injury and death. Proper selection of medication and equipment, monitoring and adequate training may prevent these adverse events.

After the procedure

The child who has received sedation and analgesia must be observed in a suitably equipped recovery location, which is equipped with suction apparatus, has the capacity to provide more than 90% oxygen and positive pressure ventilation (pediatric circuit or Ambu bag). The patient’s vital signs should be recorded at specific intervals. If the child is not fully alert, one must continue to monitor oxygen saturation and heart rate until appropriate discharge criteria are met. Patients who have received medication with a long half-life (e.g., chloral hydrate) or reversal agents, such as flumazenil or naloxone, will require a longer period of observation, since the half-life of these reversal agents is short. Appropriate instructions to families should be given, along with details of whom to contact should there be any complications or queries.

Expert commentary

Sedation and analgesia in children for procedures outside the operating room is rapidly expanding, and is being driven to be more cost effective and efficient. Highly motivated and organized sedation/anesthesia services are likely to reduce serious adverse outcomes, but minor adverse events are actually common. The majority of the adverse events associated with pediatric sedation and analgesia are respiratory/airway related, which can be managed with simple maneuvers. Implementing the pediatric sedation guidelines of the AAP and ASA could lead to a reduction in the incidence of adverse events related to sedation, and hence a reduction in morbidity and mortality. There should be a real collaboration between the anesthesiology department and other concerned departments to enhance the safe and effective management of pediatric sedation and analgesia outside the operating room.

Five-year view

With the increasing frequency of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in children, the demand for sedation and analgesia for children outside the operating room setting is exceeding the capacity of anesthesia services. The number of children requiring sedation outside the operating room may approach the number of children requiring anesthesia in the operating room in 5 years time, and as a result, more nonanesthesiologists could be asked to provide procedural sedation outside the operating room. Hospitals are likely to set up multidisciplinary pediatric sedation teams that will not only administer procedural sedation, but will also be responsible for training and credentialing for all nonanesthesiologists in procedural sedation. The anesthesiology department should collaborate with other providers and establish structured training involving human simulation with emphasis on critical events. There is a need for pharmacological agents with minimal respiratory and cardiovascular depression, and newer drugs such as the α-2 agonist dexmedetomidine offer significant advantages and a huge potential for widespread use. Utilization of brain function monitors, such as the BIS, and respiratory monitors, such as end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, will be routinely used to provide safe and effective sedation. Results from the pediatric sedation research consortium and other studies could help us to identify strategies to prevent and manage adverse events during procedural sedation in children.

Table 1. SOAPME check list.

Table 2. Pharmacological agents used for sedation and their adverse events.

Key issues

• The demand for procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room has been increasing in the last decade.

• The primary objectives of procedural sedation and analgesia are to allay anxiety, achieve immobilization of the child and obtain cooperation, reduce pain and discomfort, and induce sedation and amnesia.

• The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has mandated that anesthesiologists are responsible for developing institutional guidelines for pediatric sedation.

• The medication used, level of sedation provided, monitoring used and degree of training of sedation providers varies across the institutions.

• The majority of adverse events during sedation and analgesia are related to airway or respiratory events, which can be managed with simple maneuvers such as supplemental oxygen, opening the airway or assisted ventilation using bag–mask.

• Simulator training offers promising technology in the promotion of safe administration of pediatric procedural sedation.

• Preprocedural health evaluation before sedation should be performed by an appropriately licensed practitioner.

• Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation and heart rate, capnography and intermittent measurement of blood pressure should be documented.

• Adequate preparation, including selection of equipment, medication and monitors, is critical for the safe conduct of procedural sedation in children.

• After the child has received sedation and analgesia he/she must be observed in a suitably equipped recovery location.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Krauss B. Sedation and analgesia for procedures in children. N. Engl. J. Med.342(13), 938–945 (2000).

- Krauss B, Green SM. Procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Lancet367(9512), 766–780 (2006).

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. JCAHO, Oakland, IL, USA (2000).

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology96(4), 1004–1017 (2002).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Drugs. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: addendum. Pediatrics110(4), 836–838 (2002).

- Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Tait AR. Adverse events and risk factors associated with the sedation of children by nonanesthesiologists. Anesth. Analg.85(6), 1207–1213 (1997).

- Cote CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: analysis of medications used for sedation. Pediatrics106(4), 633–644 (2000).

- Cote CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: a critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics105(4 Pt 1), 805–814 (2000).

- Lightdale JR, Valim C, Mahoney LB, Wong S, Dinardo J, Goldmann DA. Agitation during procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila)49(1), 35–42 (2009).

- Cravero JP, Blike GT, Beach M et al. Incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics118(3), 1087–1096 (2006).

- Cravero JP, Beach ML, Blike GT, Gallagher SM, Hertzog JH. The incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia with propofol for procedures outside the operating room: a report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Anesth. Analg.108(3), 795–804 (2009).

- Cravero JP. Risk and safety of pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol.22(4), 509–513 (2009).

- Green SM, Rothrock SG, Lynch EL et al. Intramuscular ketamine for pediatric sedation in the emergency department: safety profile in 1,022 cases. Ann. Emerg. Med.31(6), 688–697 (1998).

- Slonim AD, Ognibene FP. Sedation for pediatric procedures, using ketamine and midazolam, in a primarily adult intensive care unit: a retrospective evaluation. Crit. Care Med.26(11), 1900–1904 (1998).

- McCarver-May DG, Kang J, Aouthmany M et al. Comparison of chloral hydrate and midazolam for sedation of neonates for neuroimaging studies. J. Pediatr.128(4), 573–576 (1996).

- Merola C, Albarracin C, Lebowitz P, Bienkowski RS, Barst SM. An audit of adverse events in children sedated with chloral hydrate or propofol during imaging studies. Pediatr. Anaesth.5(6), 375–378 (1995).

- Guidelines for the elective use of conscious sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia in pediatric patients. Committee on Drugs. Section on anesthesiology. Pediatrics76(2), 317–321 (1985).

- Goodson JM, Moore PA. Life-threatening reactions after pedodontic sedation: an assessment of narcotic, local anesthetic, and antiemetic drug interaction. J. Am. Dent. Assoc.107(2), 239–245 (1983).

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs: Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pediatrics89(6 Pt 1), 1110–1115 (1992).

- Pitetti R, Davis PJ, Redlinger R, White J, Wiener E, Calhoun KH. Effect on hospital-wide sedation practices after implementation of the 2001 JCAHO procedural sedation and analgesia guidelines. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med.160(2), 211–216 (2006).

- Hoffman GM, Nowakowski R, Troshynski TJ, Berens RJ, Weisman SJ. Risk reduction in pediatric procedural sedation by application of an American Academy of Pediatrics/American Society of Anesthesiologists process model. Pediatrics109(2), 236–243 (2002).

- Green SM. Fasting is a consideration – not a necessity – for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia. Ann. Emerg. Med.42(5), 647–650 (2003).

- Green SM, Krauss B. Pulmonary aspiration risk during emergency department procedural sedation – an examination of the role of fasting and sedation depth. Acad. Emerg. Med.9(1), 35–42 (2002).

- Roback MG, Bajaj L, Wathen JE, Bothner J. Preprocedural fasting and adverse events in procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department: are they related? Ann. Emerg. Med.44(5), 454–459 (2004).

- Blike GT, Christoffersen K, Cravero JP, Andeweg SK, Jensen J. A method for measuring system safety and latent errors associated with pediatric procedural sedation. Anesth Analg101(1), 48–58, table of contents (2005).

- Roback MG, Wathen JE, Bajaj L, Bothner JP. Adverse events associated with procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department: a comparison of common parenteral drugs. Acad. Emerg. Med.12(6), 508–513 (2005).

- Powers KS, Nazarian EB, Tapyrik SA et al. Bispectral index as a guide for titration of propofol during procedural sedation among children. Pediatrics115(6), 1666–1674 (2005).

- Deitch K, Miner J, Chudnofsky CR, Dominici P, Latta D. Does end tidal CO2 monitoring during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia with propofol decrease the incidence of hypoxic events? A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Emerg. Med.55(3), 258–264 (2010).

- Qadeer MA, Vargo JJ, Dumot JA et al. Capnographic monitoring of respiratory activity improves safety of sedation for endoscopic cholangiopancreatography and ultrasonography. Gastroenterologies136(5), 1568–1576; quiz 1819–1820 (2009).

- Bhatt M, Kennedy RM, Osmond MH et al. Consensus-based recommendations for standardizing terminology and reporting adverse events for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Ann. Emerg. Med.53(4), 426–435 (2009).

- Burgoyne LL, Anghelescu DL. Intervention steps for treating laryngospasm in pediatric patients. Pediatr. Anaesth.18(4), 297–302 (2008).

- Soares RR, Heyden EG. Treatment of laryngeal spasm in pediatric anesthesia by retro auricular digital pressure. Case report. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol.58(6), 631–636 (2008).

Pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room: anticipating, avoiding and managing complications

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to http://www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit is acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US and want to obtain an AMA PRA CME credit, please complete the questions online, print the certificate and present it to your national medical association.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. Based on the above review by Drs. Ramaiah and Bhananker, which of the following statements about general principles of pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room is correct?

□ A Relief of anxiety is not a primary goal of procedural sedation in the pediatric population

□ B Institutional guidelines for pediatric sedation practice should be developed by pediatricians

□ C Sedation of pediatric patients outside the operating room setting is well standardized across institutions

□ D To describe the continuum of the sedation spectrum, current guidelines use the terminology of minimal, moderate, and deep sedation and general anesthesia

2. Your patient is a 6-year-old boy undergoing closed reduction of a simple fracture of the distal forearm. Based on the above review, which of the following statements concerning adverse events associated with procedural sedation outside the operating room is most likely correct?

□ A Most adverse events during sedation and analgesia are related to cardiovascular events

□ B Causes of adverse events include drug overdose, inadequate monitoring, drug errors, inadequate skills of the staff administering drugs, and premature discharge

□ C Most respiratory adverse events require endotracheal intubation

□ D The route of drug administration is an important predictor of negative outcome

3. Based on the above review, which of the following statements would most likely apply to strategies to prevent adverse events and improve safety during sedation for the fracture reduction of the patient described in question 2?

□ A Preprocedural health evaluation before sedation may be performed by an emergency department clerk

□ B A technician may administer anxiolytic medications without medical supervision

□ C Pulse oximetry and cardiorespiratory monitoring are not required

□ D Age- and size-appropriate equipment and appropriate medications to sustain life should be checked before sedation and should be immediately available