Abstract

Around 40–60% of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder do not show adequate response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Augmentation strategies are recommended in people who show partial response to SSRI treatment or poor response to multiple SSRIs. In this article, the authors review the evidence for augmentation strategies. The available evidence is predominantly based on small-scale, randomized controlled trials, open-label trials and case series. Antipsychotic augmentation, especially risperidone, haloperidol, aripiprazole and cognitive-behavior therapy have shown the best evidence. Ondansetron, memantine, riluzole, clomipramine, mirtazapine and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area show some preliminary evidence. Ablative neurosurgery or deep brain stimulation may be tried in carefully selected treatment refractory patients.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at www.medscape.org/journal/www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 31 January 2013; Expiration date: 31 January 2014

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Describe use of antipsychotics as augmentation strategies in patients with OCD, based on a review

• Describe use of other pharmacotherapy as augmentation strategies in patients with OCD, based on a review

• Describe use of nonpharmacological therapies as augmentation strategies in patients with OCD, based on a review

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti

Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK

Disclosure: Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Laurie Barclay, MD, Freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC.

Disclosure: Laurie Barclay, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relatinoships.

Disclosure:

AUTHORS AND CREDENTIALS

Shyam Sundar Arumugham, MD, DNB, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS),Bangalore, India

Disclosure: Shyam Sundar Arumugham, MD, DNB, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Janardhan YC Reddy, DMM, MD, Professor of Psychiatry

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Clinic, Department of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, India

Disclosure: Janardhan YC Reddy, DMM, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

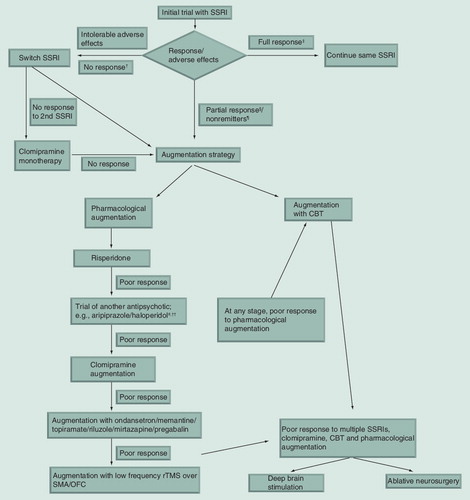

†Less than 25% reduction in the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) total score and Clinical Global Impression (CGI)-I of 4 suggests nonresponse to treatment

‡35% reduction in the Y-BOCS score or CGI-I of 1 or 2 suggest full response to treatment.

§Partial response defined as 25–35% reduction in Y-BOCS score despite adequate treatment duration with SSRI.

¶Have not achieved remission of symptoms (<16 on Y-BOCS) despite adequate treatment with SSRI.

#Haloperidol may be especially useful in patients with comorbid tic disorder.

††Olanzapine and quetiapine augmentation are options before proceeding to clomipramine augmentation.

CBT: Cognitive-behavior therapy; OFC: Orbitofrontal cortex; rTMS: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SMA: Supplementary motor area; SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common psychiatric illness with a lifetime prevalence of 2–2.5% Citation[1]. It affects individuals in the most productive period of life. It usually has an onset in childhood or early adulthood Citation[2], and more commonly runs an unremitting course persisting into adulthood Citation[3]. Disability and quality-of-life impairment in people suffering from OCD have been comparable with that of serious mental illness like schizophrenia Citation[4]. Despite this, it is a highly under-recognized condition and conservative estimates suggest that more than half of patients do not receive any treatment Citation[5]. Even among those receiving treatment, a large proportion receive inadequate or improper treatment Citation[6].

Prior to the 1960s, OCD was considered an untreatable condition. The demonstration that an antidepressant with a more selective serotonergic action, namely clomipramine, was more effective in controlling the symptoms revolutionized the treatment of OCD. Since then, the efficacy of clomipramine in the treatment of OCD has been demonstrated in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) Citation[7]. Due to the adverse effects commonly observed in people treated with clomipramine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have taken over clomipramine as the first-line agents in the treatment of OCD. Several RCTs have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of OCD Citation[8], albeit at a higher than usual antidepressant dosage and a longer time (8–12 weeks) for improvement Citation[9].

It has been observed that all SSRIs are equally efficacious in OCD Citation[8], and the choice of SSRI is usually made based on other factors like adverse effect profile, comorbidity, and so on. People who do not respond to one SSRI may respond to a second one Citation[9]. Clomipramine is generally recommended when treatment with at least two SSRIs have failed Citation[9]. The other effective treatment is cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) Citation[10], which along with SSRIs are considered to be first-line treatments for OCD Citation[11]. But considering the time constraints and requirement of highly skilled professionals, this effective treatment may not be easily accessible to everyone. Hence, SSRIs are often the first-line treatments for OCD.

Nearly 40–60% of patients treated with SSRIs do not respond to treatment or only respond partially Citation[12]. It is generally recommended that augmentation with other treatments, either medications or CBT, is suitable for people with partial response, while switching over to a different SSRI is recommended for people who do not respond.

What is augmentation?

Augmentation refers to the process of adding medications with a different mechanism of action to the primary drug to boost its therapeutic efficacy. Evidence from basic science research suggests that multiple neurotransmitters may be relevant in the pathophysiology of OCD. Hence using a combination of medications with different mechanisms of action has a theoretical rationale. In this article, the authors review efficacy and tolerability of different augmentation strategies in the treatment of OCD.

The treatment literature in OCD is marred by varied definitions of treatment response outcome, making it hard to interpret the findings of published studies. The terms like ‘response’, ‘remission’, ‘treatment resistance’ and ‘treatment refractory’ may not convey the same meaning in different studies. Nevertheless, most of the studies either use the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Citation[13], either alone or along with the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale. The term ‘treatment-resistant’ is sometimes used to describe patients who do not respond satisfactorily to any first-line therapy, and the term ‘treatment-refractory’ is used to describe patients who do not respond satisfactorily to all available therapeutic alternatives Citation[14,15]. Some authors have tried to differentiate ‘drug resistance’ from ‘treatment resistance’; the former referring to patients who have not responded to SSRIs and the latter to both SSRIs and behavior therapy Citation[16]. There is no clear consensus on the definition of treatment refractory OCD. For example, Denys et al., for their study on deep brain stimulation, defined treatment refractory OCD as nonresponse or insufficient response to at least two treatments with SSRIs at maximum dosage for at least 12 weeks, plus one treatment with clomipramine at maximum dosage for at least 12 weeks, plus at least one augmentation trial with an atypical antipsychotic for 8 weeks in combination with a SSRI, plus at least one CBT trial for a minimum of 16 sessions Citation[17]. In another study that examined the efficacy of bilateral capsulotomy, patients were considered refractory to treatment if medications, psychotherapy or CBT administered for more than 5 years did not result in clinical improvement or led to worsening Citation[18]. This study included patients who were refractory to medications alone.

In an effort to clear this confusion, expert consensus-based outcome criteria have been proposed by Pallanti et al. Citation[12]. They defined various stages of treatment response from Stage I to VII. Stage I, termed as recovery, includes those who score <8 on Y-BOCS after treatment. Remission (Stage II) is defined as <16 score on Y-BOCS. A 35% reduction in the Y-BOCS score or CGI-I of 1 or 2 suggest full response to treatment (Stage III), while a Y-BOCS reduction of 25–35% suggests partial response (Stage IV). Less than 25% reduction in the Y-BOCS total score and a CGI-I of 4 suggests nonresponse to treatment (Stage V), while relapse (Stage VI) is defined as CGI-I 6 or 25% increase in Y-BOCS from remission score. Refractory (Stage VII) patients include those who show no change or worsening with all available therapies. Pallanti et al. Citation[12] also suggest levels of nonresponse to treatment, based on the number and types of treatment, which range from level 1 (SSRI or CBT) to level 10 (which include all available treatments including neurosurgery). These are not widely used in the treatment literature.

Augmentation strategies may be useful in three groups of patients. The first group includes those who respond partially to SSRI treatment. The authors define this group as patients who show 25–35% reduction in Y-BOCS score after adequate treatment with an SSRI. The second group includes those who have shown response to medications (greater than 35% reduction on the Y-BOCS), but have not achieved remission of symptoms (i.e., <16 on Y-BOCS). The third group includes those who do not respond to at least adequate trials of two SSRIs. For the third group, clomipramine may be considered before augmentation as there is some evidence that clomipramine may be superior to SSRIs in treatment of OCD Citation[7].

With this background, the authors review the literature on the efficacy of augmentation strategies in OCD and provide a recommendation for the use of augmenting strategies based on the available literature.

Method

A MEDLINE literature search using PUBMED was conducted for all studies up to August 2012 using the search strategy (OCD) AND (augmentation) OR (adjunctive) OR (refractory) OR (resistant). The individual treatments obtained using this strategy were used as key words along with the keyword ‘obsessive–compulsive disorder’ (e.g., ‘cognitive behavior therapy’ AND ‘obsessive–compulsive disorder’, ‘risperidone’ AND ‘OCD’, and so on). In addition, the reference sections of major articles and reviews (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) were also screened. The authors included all types of studies including case series, open-label studies, controlled studies and systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Augmentation strategies in OCD

Antipsychotic medications

Antipsychotics were one of the first medications to be tried for treatment of OCD. The earlier use of antipsychotics as monotherapy for obsessive-compulsive symptoms was prompted by the effectiveness of these agents in Tourette’s syndrome, which has phenomenological similarities with OCD. There are very few if any well designed studies on antipsychotic monotherapy for OCD. Clozapine monotherapy was found to be ineffective in an open-label trial in treatment refractory OCD patients Citation[19]. An open-label study on aripiprazole has shown some positive response Citation[20]. However, these studies are too preliminary for clinical application. By far, the majority of antipsychotic studies in OCD have been as an augmentation strategy for SSRIs. Thirteen double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials and three active comparator studies have been published to date on the efficacy of augmentation with antipsychotics in treatment-resistant OCD. Most of the RCTs have been conducted with atypical antipsychotics. All these studies have a modest sample size (10–20 patients in each arm) and are heterogeneous in methodology, including the dosage, inclusion criteria and outcome measurements. Hence the results of these studies should be interpreted with caution.

Efficacy of antipsychotic augmentation

A recent meta-analysis of 12 placebo-controlled trials (excluding the Sayyah et al. Citation[21] study on aripiprazole) Citation[22] homogenized the outcome criteria from all the studies using the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Citation[13] scores and analyzed the outcome both as a continuous variable (Y-BOCS changes using standardized mean differences with the associated 95% CI) and as a categorical variable (responders defined as ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS score). On both analyses, antipsychotic drugs as a group showed significant improvement compared with placebo. 28% of the patients on antipsychotics were classified as responders compared with 13% in the placebo, with a relative risk of 2.10 (N = 12; n = 394; 95% CI: 1.16–3.80). The number needed to treat (NNT) was 5.9, which is reasonably good considering the prevalence of the problem and the paucity of treatment options. Earlier meta-analyses have also reported significant benefits with antipsychotic augmentation Citation[23–26], some reporting a better NNT of 4.5 Citation[23,25]. Methodological variations could have contributed to these minor differences. These meta-analyses also ruled out the evidence for publication bias Citation[23,25]. The only other study which has not been included in the meta-analyses Citation[21] showed a positive response to aripiprazole. Hence, there is adequate evidence for the use of antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI-resistant OCD.

Predictors of treatment response to antipsychotics

Comorbidity with tic disorder

One of the commonly cited predictors for treatment response to antipsychotics is the presence of a comorbid tic disorder. Earlier studies with typical antipsychotics Citation[27,28] revealed a better response to antipsychotic augmentation in people with comorbid tics. However, later studies of atypical antipsychotics like risperidone Citation[29], olanzapine Citation[30] and quetiapine Citation[31] failed to reveal such an association. The meta-analysis by Bloch et al. Citation[23] favored the association. The NNT increased from 5.9 in people without tic disorder to 2.3 in those with tic disorders. But the meta-analysis by Skapinakis et al. Citation[24] failed to find an association between comorbid tic disorder and treatment response. However, a later subgroup analysis revealed that in people with comorbid tic disorder, a higher dosage of antipsychotics lead to a better response. Hence, it appears that in people with comorbid tic disorders, an antipsychotic at a higher dosage (resulting in greater D2 receptor blockade) may lead to a better response.

Comorbid schizotypal personality disorder

Not many studies have addressed this issue, perhaps due to the relative rarity of patients with schizotypal disorder. Open-label trials Citation[28,32] have supported the notion that OCD patients with comorbid schizotypal personality disorder have greater improvement with antipsychotics. However, an RCT with risperidone Citation[29] did not support this conclusion.

Neuroimaging predictors

Using functional neuroimaging by FDG-PET, Buchsbaum et al. evaluated predictors of response to risperidone augmentation in SSRI nonresponders Citation[33]. They found that patients with low relative metabolic rates in the striatum and high relative metabolic rates in the anterior cingulate gyrus showed a better response to risperidone augmentation. Lower metabolic activity in the right caudate has also been found to be associated with poor response to SSRIs Citation[34]. Fineberg et al. Citation[35] suggest that this may be a probable radiological endophenotype of SSRI-resistant antipsychotic responsive OCD. However, this finding has not yet been replicated.

Other clinical variables

Carey et al. Citation[36] evaluated the predictors of response for quetiapine augmentation using logistic regression analysis. In this study, fewer previously failed SSRI trials, higher overall baseline scores for obsessions and compulsions, as well as counting/ordering and arranging compulsions, were associated with better response to quetiapine.

Duration of SSRI trial

Meta-analyses Citation[22,25] show that in studies with a duration of SSRI trial less than 10–12 weeks before augmentation, there were no significant differences between an antipsychotic drug and placebo. This could be due to the continued improvement with SSRI in the placebo group leading to lack of significant difference between the groups. These results are at odds with a recent placebo-controlled trial Citation[37], which showed that addition of quetiapine to citalopram, even in drug-naive or drug-free patients, lead to better improvement rates.

Choice of antipsychotics

Risperidone

Risperidone Citation[22–24,26] is the only antipsychotic that is consistently effective as an augmentation strategy when compared with placebo. Three placebo-controlled RCTs Citation[29,38,39], one placebo-controlled crossover trial with haloperidol Citation[40] and multiple open-label trials (e.g., Citation[41,42]) have shown positive response to risperidone. There is no negative trial with risperidone.

Quetiapine

It has been studied in five double-blind placebo-controlled trials Citation[31,37,43–45], one single-blind placebo-controlled trial Citation[46] and many open-label trials Citation[47,48]. Barring a few negative results Citation[31,48], most of the studies have shown a positive response to quetiapine. However, meta-analysis results have been unfavorable with only one Citation[26] out of four meta-analyses showing positive results with quetiapine.

Olanzapine

Despite positive results from open-label trials Citation[32,49], the two placebo-controlled RCTs have shown conflicting results Citation[30,50]. Meta-analyses of these two studies also failed to find a significant response. In an 8-week, single-blind, randomized trial comparing risperidone and olanzapine augmentation, both were equally efficacious Citation[51]. Nevertheless, more studies are needed before commenting on the clinical utility of olanzapine in OCD.

Aripiprazole

Data from multiple case series Citation[52,53] and two placebo-controlled RCTs Citation[21,54] have demonstrated the efficacy of aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant OCD.

Other antipsychotics

The efficacy of haloperidol as an augmenting agent in OCD has been demonstrated in a randomized placebo-controlled trial Citation[27] and in a brief placebo-controlled crossover trial with risperidone Citation[40]. The evidence for other antipsychotics, such as amisulpride Citation[55] and pimozide Citation[28], is in the form of case series.

To summarize, risperidone appears to be the drug of choice when an antipsychotic is considered for augmentation in OCD, followed by aripiprazole and haloperidol, while olanzapine and quetiapine need to be studied further. It is not clear whether this apparent difference in efficacy among antipsychotics is due to methodological variations in studies or due to a true difference. A head-to-head comparative trial between olanzapine and risperidone did not demonstrate any difference in the efficacy between the two agents Citation[51]. Hence, further studies are necessary to clarify this issue.

Dose of antipsychotics

Two meta-analyses Citation[22,24] demonstrated that medium to higher dosages of antipsychotics are more effective in treatment augmentation than lower doses, while low doses were not significantly more effective than placebo. Skapinakis Citation[24] classified the dosages based on the ability to block at least 60–65% of the dopamine D2 receptors, that is, dosages traditionally required for antipsychotic effect. This is equivalent to 2 mg of risperidone, 10 mg of olanzapine, 400 mg of quetiapine and 2 mg of haloperidol. Taking into consideration the findings of meta-analyses and the doses employed in individual studies , it appears that moderate doses may be more effective than very low doses. At the same time, it appears that standard antipsychotic dosages (e.g., 4–6 mg of risperidone, 15–20 mg of olanzapine, 600–800 mg of quetiapine and 10–20 mg of haloperidol) may not be employed for augmentation strategy.

Duration of antipsychotic treatment

Conflicting evidence exists on the minimum duration of antipsychotic treatment for treatment response. The meta-analysis by Skapinakis et al. Citation[24] suggested that studies with treatment duration of at least 8 weeks showed a statistically significant result, while this was not evident in the group of studies with lesser duration. Bloch et al. Citation[23] demonstrated in their analysis that treatment of more than 4 weeks may not confer an additional advantage. Individual studies tracking the improvement over time Citation[29,46] have found that the treatment response was apparent from 3 and 6 weeks onwards. Considering these findings, it would be advisable to continue antipsychotics for at least 6–8 weeks to assess their efficacy.

One retrospective chart review revealed that discontinuation of effective augmentation with antipsychotics leads to increased chance of relapse Citation[56]. Hence, it may be advisable to continue antipsychotics over a long-term period once they have shown improvement. Open-label trials of long-term use of antipsychotics in OCD have shown that they are generally well tolerated Citation[57], while they may be effective in the long term for at least a subset of patients Citation[58].

Tolerability of antipsychotic treatment

As expected, many trials reported adverse effects; restlessness with haloperidol and aripiprazole, weight gain with olanzapine, drowsiness, headache, dryness of the mouth and weight gain with quetiapine, sedation and dry mouth with risperidone. Meta-analysis revealed that discontinuation rates were not significantly different for the antipsychotic group compared with placebo, but stratification revealed that quetiapine had higher dropouts compared with placebo Citation[22]. The decreased tolerability of quetiapine, coupled with its doubtful efficacy precludes the use of this agent as a first-line augmentation strategy.

Mechanism of action

Atypical antipsychotics have a curious relationship with OC symptoms. While they are effective as an augmentation strategy in OCD, they have also been shown to induce de novo OC symptoms in people with psychosis Citation[59,60]. The action of atypical antipsychotic agents on both 5HT and dopamine D2 receptors have been used to explain this relationship Citation[59]. Atypical antipsychotics block 5HT receptors at low doses and the D2 blockade increases as the dose increases Citation[24]. 5HT blockade at low doses may precipitate OC symptoms and dopamine blockade at higher doses may explain their improvement of OC symptoms at higher doses. This is supported by the meta-analytic findings described above. Some clinical evidence also supports this dose–response relationship Citation[61]. But there is conflicting evidence that suggests that OC symptoms induced by clozapine can be decreased by dose reduction Citation[60]. Furthermore, in augmentation trials, usually, a lower dose of antipsychotic is used; for example, 1–2 mg of risperidone. On the other hand, OC symptoms manifest when antipsychotics are used in optimum doses in schizophrenia. Hence, the dose–response relationship is not clear. There is also a possibility that differential blockade and activation of 5HT2A and non-5HT2A receptors may play a role in their mediation of antiobsessional activity of SSRIs Citation[62]. Second generation antipsychotics, such as risperidone and olanzapine, and to an extent quetiapine, are potent antagonists of 5HT2A receptors, and also mirtazapine, which may have some antiobsessional property. There is also a suggestion that antiobsessional activity may be related to D2-blocking properties and this view is supported by the fact that risperidone and haloperidol are more effective than other antipsychotics.

Enhancing serotonergic neurotransmission

Consequent to the serotonin hypothesis, other drugs acting on the serotonin system have been tried as augmenting agents to boost the serotonergic action of SSRIs.

Ondansetron

Ondansetron is a serotonin antagonist for the 5HT3 receptor, used as an antiemetic agent. It has also been used as an anticraving agent for substance use disorders. Ondansetron was useful in a double-blinded RCT of ondansetron augmentation (4 mg/day) to low-dose fluoxetine (20 mg/day Citation[63]). Askari et al. Citation[64] conducted a two-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study on the efficacy of granisetron (1 mg twice daily), another 5HT3 antagonist, as an augmenting strategy and found it to be efficacious and well tolerated.

Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant with specific noradrenergic and serotonergic receptor antagonistic properties. It enhances serotonin neurotransmission indirectly. There is preliminary evidence of its use as an anti-obsessional agent as a monotherapy Citation[65]. Pallanti et al. Citation[66] tested the augmenting efficacy of mirtazapine (at 15–30 mg/day) for citalopram in a single-blind RCT. They found that mirtazapine was associated with earlier onset of response and reduced adverse effects. However, the final outcome did not differ between mirtazapine and placebo.

Clomipramine

Another interesting strategy is the addition of clomipramine as an augmenting strategy to SSRIs in treatment-resistant patients. It is commonly used with citalopram, perhaps because of the decreased pharmacokinetic interaction potential of citalopram. An open-label trial demonstrated a significant improvement with the combination of citalopram (40 mg/day) and clomipramine (150 mg/day) to citalopram alone Citation[67]. Another uncontrolled study demonstrated the augmentation efficacy of citalopram to clomipramine in 20 treatment-resistant patients Citation[68]. The benefit of clomipramine–fluoxetine combination has been demonstrated in two-case series and an RCT, in which this combination was superior to fluoxetine–quetiapine combination Citation[69]. Such combinations, when used, should be monitored for adverse effects, particularly cardiac events, EEG changes, myoclonus and seizures.

Buspirone

Buspirone is a 5HT1A partial agonist used in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Buspirone augmentation of SSRIs has not been found to be useful Citation[70].

Benzodiazepines

Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine with putative serotonergic properties, has been found to be ineffective as an augmenting agent in an RCT Citation[71]. The use of clonazepam as a monotherapy has yielded conflicting results in two RCTs Citation[72,73].

β-blockers

Pindolol, a β-adrenergic blocker with putative antagonistic action at presynaptic 5HT1A receptor has shown efficacy (at a dose of 2.5 mg three-times daily) as an augmenting agent to paroxetine in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in OCD patients (n = 23) resistant to treatment with at least two SSRIs Citation[74], but not in another RCT Citation[75].

Trazodone

Trazodone has antagonist action at 5HT2/1C receptors, along with serotonin reuptake inhibiting action. It was not found to be effective as a monotherapy for OCD in a small placebo-controlled trial (n = 21) Citation[76].

Glutamatergic drugs

Several lines of evidence, including genetic studies, magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies, CSF analysis and animal studies, point to a glutamatergic dysfunction in OCD Citation[77]. Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the adult brain. It has two major types of receptors; ionotropic (including the AMPA, kainate and NMDA receptors) and metabotropic receptors. Currently available drugs in the market either act on ionotropic receptors (especially the NMDA receptors) or modulate glutamate neurotransmission through other mechanisms. These drugs, which are currently used in many CNS disorders like dementia, epilepsy, amyotropic lateral sclerosis, and so on, have also been tested for their efficacy in OCD.

Riluzole

Riluzole is a glutamate modulator used in the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It is hypothesized to modulate glutamate transmission by various mechanisms, including inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels in excitatory neurons and potentiation of the extrasynaptic reuptake of glutamate in glial cells Citation[77]. Riluzole is one of the earliest glutamate modulators tried in refractory OCD. In these trials, riluzole given at 50 mg twice daily was effective in at least 50% of the patients with refractory OCD Citation[78,79]. It was well tolerated, but the few cases of pancreatitis in children on riluzole raises concern about its use.

Memantine

Memantine is an NMDA antagonist used in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Its use in OCD has been demonstrated in open-label trials Citation[80,81]. A recent RCT found significant improvement in the memantine group compared with controls Citation[82]. It was tried at a dose of 10 mg twice daily and was generally well tolerated.

Anticonvulsants

Lamotrigine is an anticonvulsant that blocks sodium channels and consequently glutamate neurotransmission. In a recent placebo-controlled RCT of 40 patients with SSRI-resistant OCD, lamotrigine addition at 100 mg/day was associated with significant improvement Citation[83].

In a placebo-controlled randomized trial Citation[84], SSRI augmentation with topiramate (mean dosage: 180.15 mg/day) in treatment nonresponders resulted in a mean decrease of 32.0% in Y-BOCS score, compared with a 2.4% decrease for those receiving placebo. In another placebo-controlled RCT Citation[85], in 36 OCD patients, topiramate (mean dosage: 177.8 ± 134.2 mg/day) resulted in significant improvement in compulsions, but not in obsessions. In this study, topiramate was not well tolerated – 28% (5/18) of the subjects discontinued the drug for adverse effects and 39% (7/18) required a dose reduction.

Pregabalin is an antiepileptic that binds to the α2δ subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel in the CNS and decreases neurotransmission in excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate. Its efficacy as an augmenting agent (at 150–675 mg/day) has been explored in uncontrolled open-label trials Citation[86,87]. Gabapentin, with a similar mechanism of action as pregabalin, hastened the response to fluoxetine, but not the efficacy Citation[88].

Ketamine

Ketamine, an NMDA antagonist with demonstrated acute antidepressant effects, was not found to be useful in an open-label trial involving ten patients with treatment refractory OCD; there was a transient decrease in OCD symptoms, unlike depressive symptoms which had a more significant improvement Citation[89].

Glycine

In contrast to other glutamatergic drugs, glycine acts as a coagonist at the NMDA receptor site and hence increases glutamate transmission. In a double-blind RCT, patients on glycine at 60 mg/day showed nonsignificant improvement in OCD symptoms, but it was associated with poor tolerability due to unpleasant taste and nausea Citation[90].

Sarcosine

Sarcosine is a glycine transporter inhibitor and increases glycine action at the receptor Citation[91]. In an open-label trial, sarcosine reported significant improvement in OCD symptoms with acceptable tolerability.

Other drugs

Stimulants

Psychostimulants increase catecholamine neurotransmission. In a double-blind RCT of dextroamphetamine (30 mg/day) and caffeine (300 mg/day) in partial responders/nonresponders to SSRIs/serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n = 24), around 50% of the patients showed improvement within the first week of treatment, and the scores improved over the study period Citation[92]. The finding suggests that psychostimulant augmentation can cause a rapid improvement in OCD, but it needs replication before further use.

Mood stabilizers

Despite initial promise, later controlled trials failed to establish the efficacy of lithium as an augmenting agent Citation[93]. There is no evidence to support the use of other mood stabilizers such as valproate and carabamazepine.

Inositol

Inositol, an isomer of glucose and a precursor in the phosphatidylinositol cycle, was effective as a monotherapy (18 mg/day) in a small, double-blind crossover trial Citation[94], but its use as an augmenting agent is not supported by recent trials Citation[95].

Opioid system

The opioid system has been reported to be involved in the pathology of OCD. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial for 2 weeks demonstrated the efficacy of once-weekly morphine, an opioid agonist, as an augmenting agent Citation[96]. The opioid antagonist naltrexone, which has been used in many impulse control disorders, has not been found to be effective in OCD as an augmenting agent. Rather, it appears to increase dysphoria in people with OCD Citation[97].

Cognitive-behavior therapy

Behavior therapy (BT) in the form of exposure and response prevention (ERP) is a first-line intervention for OCD. Cognitive interventions, usually in combination with ERP are also used commonly. Many RCTs have failed to find an advantage of combining SSRIs and CBT ab initio over either treatment alone Citation[98]. However, recent multicenter RCTs have supported this approach in adults Citation[99] and children Citation[100].

There have been many uncontrolled trials that have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT in people with partial/poor response to one or more SSRIs Citation[101]. It has also been seen that this effect persisted up to 1 year post-treatment in well-characterized SSRI nonresponders Citation[102]. These encouraging results have been confirmed by RCTs. Tolin et al. Citation[103] conducted an RCT to study the effect of either self-directed or therapist-directed CBT in 41 patients who have responded inadequately to at least one SSRI. Both treatment arms showed improvement, but the therapist-directed treatment was superior. Simpson et al. compared ERP with stress management in an RCT in 108 patients with inadequate response to SSRIs, and found ERP to be superior, with a NNT of 2 Citation[104]. A total of 74% of patients on ERP were found to be responders, compared with 22% of those on stress management training. Furthermore, 33% of patients on ERP had minimal symptoms (≤12 Y-BOCS score) after treatment compared with 4% in the other group. CBT has also been found to be superior to medications alone in pediatric patients who have experienced partial response to a previous SSRI trial, as demonstrated in the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) RCT Citation[105]. In this study, the patients were randomized into three augmentation groups, namely medication management alone, medication management plus instruction in CBT or medication management plus CBT. The CBT group performed better than the other two groups with an NNT of 3. Treatment guidelines recommend addition of behavioral therapy/CBT to people who have not responded to SSRIs Citation[201]. Considering the available evidence and the demonstrated efficacy of both the treatments individually, this seems to be a rational recommendation.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

Despite initial encouraging results from uncontrolled studies, randomized controlled studies have shown that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) applied to the right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex does not decrease obsessive compulsive symptoms significantly compared with placebo Citation[106]. The efficacy of low frequency rTMS applied over supplementary motor area (SMA) has been demonstrated in an RCT Citation[107]. In another RCT involving sequential administration of low frequency rTMS over right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and bilateral SMA, there was no significant post-treatment difference between the active group and the sham treatment group Citation[108]. From the available evidence, there is no convincing evidence to support the use of rTMS in OCD Citation[109].

Neurosurgery

Neurosurgical procedures include either ablative procedures or deep brain stimulation. With progressive improvements in precision and safety of neurosurgical techniques, they are currently being studied more as a treatment option in treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders Citation[110]. Patients are carefully selected for surgical interventions, but only when they prove to be refractory to traditional pharmacotherapy and CBT.

The common ablative procedures practiced include anterior cingulotomy, capsulotomy, subcaudate tractotomy and limbic leucotomy Citation[111]. There are no controlled or comparative studies on ablative surgeries for OCD. The use of γ-knife for surgery, especially for ventral capsulotomy (γ-ventral capsulotomy), has made surgery more precise and less invasive. The outcome is usually observed after 6 months to 2 years postsurgery. Review of the uncontrolled studies suggests that at least 50–60% of the patients show a response to surgery Citation[112]. A recent review Citation[113] suggests that capsulotomy may be a more effective procedure for OCD. There may be some rare serious adverse effects including intracerebral hemorrhage, infection, postoperative convulsions and so on which are more commonly seen with open surgeries. g-knife surgeries may lead to edema. Long lasting personality alterations and cognitive disturbances have been reported but are not frequent complications.

In deep brain stimulation, electrodes are inserted in specific regions in brain and electrical stimulation in these areas is provided through implanted neurostimulators. The mechanism of action of DBS is still not clear; it is hypothesized that it suppresses pathological network activity, while allowing normal information transmission to occur Citation[114] in the underlying brain region. The advantage with this procedure is that it is reversible and can be studied using placebo controls by sham stimulation. The disadvantage is that it is more expensive, needs battery change intermittently and is invasive compared with g-knife surgery. In OCD, electrodes are commonly implanted in the ventral capsule/ventral striatum, which includes the nucleus accumbens. The other brain regions, such as inferior thalamic peduncle and subthalamic nucleus, have also been tried. A few double-blind crossover studies have been conducted. A review of the 90 patients for whom DBS has been reported in the international literature showed that around 50% improvement occurs in OCD, depressive and anxiety symptoms Citation[115]. Adverse effects are rare and include surgical complications like intracranial hemorrhage, electrode breakage and so on, and stimulation-induced adverse effects like hypomania, agitation, anxiety and so on.

provides a summary of all RCTs of augmenting strategies other than antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of OCD.

Expert commentary

Due to limited efficacy of SSRIs, augmentation strategies have become a part of standard practice in treatment of OCD. There is little evidence at present to recommend the use of augmentation strategies ab initio. Strategies in patients who do not respond to an initial trial with an SSRI include switching to another SSRI, use of suprathreshold doses of SSRIs and use of augmenting drugs. Among these, there is satisfactory evidence for switching SSRIs and use of augmentation strategies. Augmentation is generally recommended for those who show partial response to treatment with a SSRI or those with poor response to multiple SSRIs. Switching to a different SSRI is recommended if there is no response to the initial trial with a SSRI. If response to two SSRIs is unsatisfactory, a trial with clomipramine is recommended Citation[9]. Augmentation strategies include pharmacological agents, psychotherapy and other somatic treatments. Antipsychotics are the most studied pharmacological augmenting agents. They are especially useful in people with comorbid tic disorder and perhaps schizotypal disorder. There seems to be variation in the efficacy between individual antipsychotics. Risperidone, aripiprazole and haloperidol have been found to be effective, while quetiapine and olanzapine have not been found to be effective consistently. Risperidone may currently be recommended as the antipsychotic of choice for augmentation in OCD, due to its consistent demonstration of efficacy. Aripiprazole and haloperidol are the next options. There is no evidence whether patients failing to respond to one antipsychotic may respond to another one. Antipsychotics should be used at moderate doses (e.g., 2 mg of risperidone) and may take 4–8 weeks for action.

After antipsychotics, other options are 5HT3 anatagonists, glutamatergic drugs and topiramate. However, more evidence is required to recommend their routine use as augmenting agents. Lamotrigine needs to be studied further, while ketamine has not been shown to be effective. There is preliminary evidence for drugs like pregabalin, mirtazapine, dextroamphetamine and morphine. The long-term safety and dependence potential of the dextroamphetamine and morphine preclude their regular use. Further studies on their efficacy and their long-term safety are warranted. Clomipramine augmentation may be a promising strategy, especially in people who do not tolerate high doses of a single drug, but this needs further study. Popular strategies, such as the addition of buspirone, lithium and clonazepam, have not withstood testing in well controlled trials. In essence, the best pharmacological augmenting agents are atypical antipsychotics, risperidone in particular.

CBT is one of the most effective treatments in OCD when used as a monotherapy. Its efficacy as an augmentation strategy has been demonstrated in partial responders Citation[104,105] and to an extent in nonresponders Citation[102]. Most guidelines recommend addition of CBT if response to SSRIs is not satisfactory. CBT should be tried early on instead of a series of pharmacological augmentation trials with questionable evidence.

At this point of time, rTMS cannot be recommended as a useful augmenting strategy. Neurosurgical interventions like DBS and ablative procedures should be employed judiciously in severely ill patients who are refractory to standard treatment options including intensive CBT. To conclude, among the pharmacological options, atypical antipsychotics have the best evidence as augmenting agents in OCD .

Five-year view

SSRIs and CBT have improved the outcome in people suffering from OCD. Despite this, a considerable proportion of patients do not show adequate response to treatment. Although antipsychotics have been found to be useful, they benefit only about a third of the patients. Also, the choice of antipsychotic drug, much like the choice of SSRI, remains somewhat unclear. It has to be established whether there is a real difference between the efficacies of various antipsychotics. Therefore, there is a need to compare the efficacy of different antipsychotics in head-to-head trials in OCD. The ceiling effect achieved by serotonin and dopamine-based therapies has shifted the focus toward other neurotransmitters. Glutamatergic system is an exciting frontier of approach at the moment. There have been some encouraging results from NMDA antagonists. We need larger controlled trials to verify their efficacy as augmenting agents. Drugs acting on other glutamate receptors, such as the metabotropic receptors, are currently being patented and tested Citation[116]. Augmentation with mirtazapine should be evaluated carefully in controlled trials. Agents targeting 5HT1D and 5HT2A/2C receptors, which are currently implicated in the pathogenesis of OCD, have to be studied Citation[117].

Abnormalities in neurotrophic factors, especially a decrease in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, have been demonstrated in people with OCD Citation[118]. Subcutaneous infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor has shown antidepressant-like response in preclinical studies Citation[119]. It may be a long way before such applications are tried in clinical populations.

Novel psychotherapies such as metacognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy need further study. The authors now have few studies that have examined the role of CBT in partial responders to SSRIs. Importantly, the role of CBT in SSRI nonresponsive patients needs to be examined in well-designed controlled studies. In addition, relative merits of augmentation of SSRIs with CBT and atypical antipsychotics need to be determined, since it is unclear as to what is the next best option after an initial poor response to SSRIs. The efficacy of rTMS in SMA and OFPFC has to be replicated. The brain regions implicated in OCD lie deep in the brain (e.g., anterior cingulated cortex, orbitofrontal cortex). Hence the newly invented deep coils (e.g., H-coils), which have a penetration of around 5–6 cm, have to be tested in OCD. DBS and ablative surgery have to be studied more extensively, particularly for their long-term safety and benefits.

Table 1. Randomized placebo-controlled trials of antipsychotic augmentation in treatment nonresponders/partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Table 2. Randomized controlled trials of antipsychotic augmentation with active comparators.

Table 3. Randomized controlled trials on the augmentation efficacy of other interventions in obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Key issues

• Augmentation strategies should be used in people who show partial response or poor response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

• Antipsychotic augmentation and cognitive-behavior therapy augmentation have the best evidence for efficacy.

• Among antipsychotics, risperidone has the best evidence followed by aripiprazole and haloperidol. When used, antipsychotics should be used in their minimum antipsychotic doses.

• Cognitive-behavior therapy should be tried early on in the course of illness instead of a series of pharmacological augmentation trials with questionable evidence.

• Clomipramine augmentation may be tried, especially in people not tolerating higher doses of other SSRIs.

• 5HT3 antagonists like ondansetron are promising in their efficacy as well as in decreasing gastrointestinal side effects of SSRIs.

• Glutamatergic antagonists have a sound theoretical rationale, but need to be tested rigorously.

• Traditionally recommended augmenting agents like lithium, buspirone and clonazepam are not effective. Clonazepam may help in the reduction of anxiety.

• Other strategies such as mirtazapine/pregabalin/stimulants augmentation may be tried when patients fail with the above mentioned agents.

• Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area and orbitofrontal cortex show some evidence, but it needs replication.

• Ablative neurosurgery or deep brain stimulation may be tried in carefully selected treatment refractory patients.

References

- Torres AR, Lima MC. Epidemiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 27(3), 237–242 (2005).

- McGuire JF, Lewin AB, Horng B, Murphy TK, Storch EA. The nature, assessment, and treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Postgrad. Med. 124(1), 152–165 (2012).

- Micali N, Heyman I, Perez M et al. Long-term outcomes of obsessive–compulsive disorder: follow-up of 142 children and adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 197(2), 128–134 (2010).

- Gururaj GP, Math SB, Reddy JY, Chandrashekar CR. Family burden, quality of life and disability in obsessive compulsive disorder: an Indian perspective. J. Postgrad. Med. 54(2), 91–97 (2008).

- Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull. World Health Organ. 82(11), 858–866 (2004).

- Blanco C, Olfson M, Stein DJ, Simpson HB, Gameroff MJ, Narrow WH. Treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder by U.S. psychiatrists. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67(6), 946–951 (2006).

- Ackerman DL, Greenland S. Multivariate meta-analysis of controlled drug studies for obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 22(3), 309–317 (2002).

- Soomro GM, Altman D, Rajagopal S, Oakley-Browne M. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD001765 (2008).

- Math SB, Janardhan Reddy YC. Issues in the pharmacological treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 61(7), 1188–1197 (2007).

- Rosa-Alcázar AI, Sánchez-Meca J, Gómez-Conesa A, Marín-Martínez F. Psychological treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28(8), 1310–1325 (2008).

- Kripke C. Low glycemic diets for obesity treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 77(11), 1534 (2008).

- Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C et al.; International Treatment Refractory OCD Consortium. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 5(2), 181–191 (2002).

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA et al. The Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 46(11), 1006–1011 (1989).

- Ferrão YA, Shavitt RG, Bedin NR et al. Clinical features associated to refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 94(1–3), 199–209 (2006).

- Jenike MA, Rauch SL. Managing the patient with treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: current strategies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 55, 11–17 (1994).

- Mishra B, Sahoo S, Mishra B. Management of treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: an update on therapeutic strategies. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 10(3), 145 (2007).

- Denys D, Mantione M, Figee M et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67(10), 1061–1068 (2010).

- Liu K, Zhang H, Liu C et al. Stereotactic treatment of refractory obsessive compulsive disorder by bilateral capsulotomy with 3 years follow-up. J. Clin. Neurosci. 15(6), 622–629 (2008).

- McDougle CJ, Barr LC, Goodman WK et al. Lack of efficacy of clozapine monotherapy in refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 152(12), 1812–1814 (1995).

- Connor KM, Payne VM, Gadde KM, Zhang W, Davidson JR. The use of aripiprazole in obsessive–compulsive disorder: preliminary observations in 8 patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66(1), 49–51 (2005).

- Sayyah M, Sayyah M, Boostani H, Ghaffari SM, Hoseini A. Effects of aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder (a double blind clinical trial). Depress. Anxiety 29(10), 850–854 (2012).

- Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1–18 (2012).

- Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Kelmendi B, Coric V, Bracken MB, Leckman JF. A systematic review: antipsychotic augmentation with treatment refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 11(7), 622–632 (2006).

- Skapinakis P, Papatheodorou T, Mavreas V. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonergic antidepressants in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 17(2), 79–93 (2007).

- Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S. Efficacy of antipsychotic augmentation therapy in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr. 79(8), 453–466 (2011).

- Komossa K, Depping AM, Meyer M, Kissling W, Leucht S. Second-generation antipsychotics for obsessive compulsive disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, CD008141 (2010).

- McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF, Lee NC, Heninger GR, Price LH. Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51(4), 302–308 (1994).

- McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Price LH et al. Neuroleptic addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 147(5), 652–654 (1990).

- McDougle CJ, Epperson CN, Pelton GH, Wasylink S, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57(8), 794–801 (2000).

- Shapira NA, Ward HE, Mandoki M et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine addition in fluoxetine-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 55(5), 553–555 (2004).

- Carey PD, Vythilingum B, Seedat S, Muller JE, van Ameringen M, Stein DJ. Quetiapine augmentation of SRIs in treatment refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study [ISRCTN83050762]. BMC Psychiatry 5, 5 (2005).

- Bogetto F, Bellino S, Vaschetto P, Ziero S. Olanzapine augmentation of fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD): a 12-week open trial. Psychiatry Res. 96(2), 91–98 (2000).

- Buchsbaum MS, Hollander E, Pallanti S et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of risperidone augmentation in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory patients. Neuropsychobiology 53(3), 157–168 (2006).

- Saxena S, Brody AL, Ho ML, Zohrabi N, Maidment KM, Baxter LR Jr. Differential brain metabolic predictors of response to paroxetine in obsessive–compulsive disorder versus major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 160(3), 522–532 (2003).

- Fineberg NA, Gale TM, Sivakumaran T. A review of antipsychotics in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 20(1), 97–103 (2006).

- Carey PD, Lochner C, Kidd M, Van Ameringen M, Stein DJ, Denys D. Quetiapine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: is response to treatment predictable? Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27(6), 321–325 (2012).

- Vulink NC, Denys D, Fluitman SB, Meinardi JC, Westenberg HG. Quetiapine augments the effect of citalopram in non-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 76 patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70(7), 1001–1008 (2009).

- Hollander E, Baldini Rossi N, Sood E, Pallanti S. Risperidone augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 6(4), 397–401 (2003).

- Erzegovesi S, Guglielmo E, Siliprandi F, Bellodi L. Low-dose risperidone augmentation of fluvoxamine treatment in obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15(1), 69–74 (2005).

- Li X, May RS, Tolbert LC, Jackson WT, Flournoy JM, Baxter LR. Risperidone and haloperidol augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: a crossover study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66(6), 736–743 (2005).

- Saxena S, Wang D, Bystritsky A, Baxter LR Jr. Risperidone augmentation of SRI treatment for refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 57(7), 303–306 (1996).

- Stein DJ, Bouwer C, Hawkridge S, Emsley RA. Risperidone augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive–compulsive and related disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 58(3), 119–122 (1997).

- Denys D, de Geus F, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine addition in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder refractory to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65(8), 1040–1048 (2004).

- Fineberg NA, Sivakumaran T, Roberts A, Gale T. Adding quetiapine to SRI in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled treatment study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 20(4), 223–226 (2005).

- Kordon A, Wahl K, Koch N et al. Quetiapine addition to serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients with severe obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 28(5), 550–554 (2008).

- Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Gecici O. Quetiapine augmentation in patients with treatment resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a single-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 17(3), 115–119 (2002).

- Denys D, van Megen H, Westenberg H. Quetiapine addition to serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment in patients with treatment-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open-label study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 63(8), 700–703 (2002).

- Mohr N, Vythilingum B, Emsley RA, Stein DJ. Quetiapine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 17(1), 37–40 (2002).

- Koran LM, Ringold AL, Elliott MA. Olanzapine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61(7), 514–517 (2000).

- Bystritsky A, Ackerman DL, Rosen RM et al. Augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder using adjunctive olanzapine: a placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65(4), 565–568 (2004).

- Maina G, Pessina E, Albert U, Bogetto F. 8-week, single-blind, randomized trial comparing risperidone versus olanzapine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18(5), 364–372 (2008).

- Matsunaga H, Hayashida K, Maebayashi K, Mito H, Kiriike N. A case series of aripiprazole augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-refractory obsessive compulsive disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 15(4), 263–269 (2011).

- Higuma H, Kanehisa M, Maruyama Y et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in 13 patients with refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: a case series. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 13(1), 14–21 (2012).

- Muscatello MR, Bruno A, Pandolfo G et al. Effect of aripiprazole augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors or clomipramine in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 31(2), 174–179 (2011).

- Metin O, Yazici K, Tot S, Yazici AE. Amisulpiride augmentation in treatment resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open trial. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 18(6), 463–467 (2003).

- Maina G, Albert U, Ziero S, Bogetto F. Antipsychotic augmentation for treatment resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: what if antipsychotic is discontinued? Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 18(1), 23–28 (2003).

- Marazziti D, Pfanner C, Dell’Osso B et al. Augmentation strategy with olanzapine in resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: an Italian long-term open-label study. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 19(4), 392–394 (2005).

- Matsunaga H, Nagata T, Hayashida K, Ohya K, Kiriike N, Stein DJ. A long-term trial of the effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotic agents in augmenting SSRI-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70(6), 863–868 (2009).

- Lykouras L, Alevizos B, Michalopoulou P, Rabavilas A. Obsessive–compulsive symptoms induced by atypical antipsychotics. A review of the reported cases. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 27(3), 333–346 (2003).

- Schirmbeck F, Zink M. Clozapine-induced obsessive–compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: a critical review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 10(1), 88–95 (2012).

- Ramasubbu R, Ravindran A, Lapierre Y. Serotonin and dopamine antagonism in obsessive–compulsive disorder: effect of atypical antipsychotic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry 33(6), 236–238 (2000).

- Marek GJ, Carpenter LL, McDougle CJ, Price LH. Synergistic action of 5-HT2A antagonists and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(2), 402–412 (2003).

- Soltani F, Sayyah M, Feizy F, Malayeri A, Siahpoosh A, Motlagh I. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of ondansetron for patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 25(6), 509–513 (2010).

- Askari N, Moin M, Sanati M et al. Granisetron adjunct to fluvoxamine for moderate to severe obsessive–compulsive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs 26(10), 883–892 (2012).

- Koran LM, Gamel NN, Choung HW, Smith EH, Aboujaoude EN. Mirtazapine for obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open trial followed by double-blind discontinuation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66(4), 515–520 (2005).

- Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Bruscoli M. Response acceleration with mirtazapine augmentation of citalopram in obsessive–compulsive disorder patients without comorbid depression: a pilot study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65(10), 1394–1399 (2004).

- Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Paiva RS, Koran LM. Citalopram for treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 14(2), 101–106 (1999).

- Marazziti D, Golia F, Consoli G et al. Effectiveness of long-term augmentation with citalopram to clomipramine in treatment-resistant OCD patients. CNS Spectr. 13(11), 971–976 (2008).

- Diniz JB, Shavitt RG, Pereira CA et al. Quetiapine versus clomipramine in the augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a randomized, open-label trial. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 24(3), 297–307 (2010).

- Grady TA, Pigott TA, L’Heureux F, Hill JL, Bernstein SE, Murphy DL. Double-blind study of adjuvant buspirone for fluoxetine-treated patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 150(5), 819–821 (1993).

- Crockett BA, Churchill E, Davidson JR. A double-blind combination study of clonazepam with sertraline in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 16(3), 127–132 (2004).

- Hewlett WA, Vinogradov S, Agras WS. Clomipramine, clonazepam, and clonidine treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 12(6), 420–430 (1992).

- Hollander E, Kaplan A, Stahl SM. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of clonazepam in obsessive–compulsive disorder. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 4(1), 30–34 (2003).

- Dannon PN, Sasson Y, Hirschmann S, Iancu I, Grunhaus LJ, Zohar J. Pindolol augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10(3), 165–169 (2000).

- Mundo E, Guglielmo E, Bellodi L. Effect of adjuvant pindolol on the antiobsessional response to fluvoxamine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 13(5), 219–224 (1998).

- Pigott TA, L’Heureux F, Rubenstein CS, Bernstein SE, Hill JL, Murphy DL. A double-blind, placebo controlled study of trazodone in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 12(3), 156–162 (1992).

- Pittenger C, Bloch MH, Williams K. Glutamate abnormalities in obsessive compulsive disorder: neurobiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 132(3), 314–332 (2011).

- Grant P, Lougee L, Hirschtritt M, Swedo SE. An open-label trial of riluzole, a glutamate antagonist, in children with treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 17(6), 761–767 (2007).

- Coric V, Taskiran S, Pittenger C et al. Riluzole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open-label trial. Biol. Psychiatry 58(5), 424–428 (2005).

- Aboujaoude E, Barry JJ, Gamel N. Memantine augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open-label trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 29(1), 51–55 (2009).

- Stewart SE, Jenike EA, Hezel DM et al. A single-blinded case–control study of memantine in severe obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 30(1), 34–39 (2010).

- Ghaleiha A, Entezari N, Modabbernia A et al. Memantine add-on in moderate to severe obsessive–compulsive disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Psychiatr. Res. (2012).

- Bruno A, Micò U, Pandolfo G et al. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 26(11), 1456–1462 (2012).

- Mowla A, Khajeian AM, Sahraian A, Chohedri AH, Kashkoli F. Topiramate augmentation in resistant OCD: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. (2010) (Epub ahead of print).

- Berlin HA, Koran LM, Jenike MA et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72(5), 716–721 (2011).

- Oulis P, Mourikis I, Konstantakopoulos G. Pregabalin augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 26(4), 221–224 (2011).

- Di Nicola M, Tedeschi D, Martinotti G et al. Pregabalin augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder: a 16-week case series. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 31(5), 675–677 (2011).

- Onder E, Tural U, Gökbakan M. Does gabapentin lead to early symptom improvement in obsessive–compulsive disorder? Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 258(6), 319–323 (2008).

- Bloch MH, Wasylink S, Landeros-Weisenberger A et al. Effects of ketamine in treatment-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 72(11), 964–970 (2012).

- Greenberg WM, Benedict MM, Doerfer J et al. Adjunctive glycine in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder in adults. J. Psychiatr. Res. 43(6), 664–670 (2009).

- Wu PL, Tang HS, Lane HY, Tsai CA, Tsai GE. Sarcosine therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: a prospective, open-label study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 31(3), 369–374 (2011).

- Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, Gamel NN. Double-blind study of dextroamphetamine versus caffeine augmentation for treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70(11), 1530–1535 (2009).

- McDougle CJ, Price LH, Goodman WK, Charney DS, Heninger GR. A controlled trial of lithium augmentation in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive–compulsive disorder: lack of efficacy. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 11(3), 175–184 (1991).

- Fux M, Levine J, Aviv A, Belmaker RH. Inositol treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 153(9), 1219–1221 (1996).

- Fux M, Benjamin J, Belmaker RH. Inositol versus placebo augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a double-blind cross-over study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2(3), 193–195 (1999).

- Koran LM, Aboujaoude E, Bullock KD, Franz B, Gamel N, Elliott M. Double-blind treatment with oral morphine in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66(3), 353–359 (2005).

- Amiaz R, Fostick L, Gershon A, Zohar J. Naltrexone augmentation in OCD: a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18(6), 455–461 (2008).

- Albert U, Barbaro F, Aguglia A, Maina G, Bogetto F. Combined treatments in obsessive–compulsive disorder: current knowledge and future prospects. Riv. Psichiatr. 47(4), 255–268 (2012).

- Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 162(1), 151–161 (2005).

- The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: the pediatric OCD treatment study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292(16), 1969–1976 (2004).

- Tundo A, Salvati L, Busto G, Di Spigno D, Falcini R. Addition of cognitive-behavioral therapy for nonresponders to medication for obsessive–compulsive disorder: a naturalistic study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68(10), 1552–1556 (2007).

- Anand N, Sudhir PM, Math SB, Thennarasu K, Janardhan Reddy YC. Cognitive behavior therapy in medication non-responders with obsessive–compulsive disorder: a prospective 1-year follow-up study. J. Anxiety Disord. 25(7), 939–945 (2011).

- Tolin DF, Hannan S, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Worhunsky P, Brady RE. A randomized controlled trial of self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder patients with prior medication trials. Behav. Ther. 38(2), 179–191 (2007).

- Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 165(5), 621–630 (2008).

- Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 306(11), 1224–1232 (2011).

- Blom RM, Figee M, Vulink N, Denys D. Update on repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder: different targets. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 13(4), 289–294 (2011).

- Mantovani A, Simpson HB, Fallon BA, Rossi S, Lisanby SH. Randomized sham-controlled trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 13(2), 217–227 (2010).

- Kang JI, Kim CH, Namkoong K, Lee CI, Kim SJ. A randomized controlled study of sequentially applied repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70(12), 1645–1651 (2009).

- Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, Sommer IE. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71(7), 873–884 (2010).

- Greenberg BD, Price LH, Rauch SL et al. Neurosurgery for intractable obsessive–compulsive disorder and depression: critical issues. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 14(2), 199–212 (2003).

- Lopes AC, Mathis ME, Canteras MM, Salvajoli JV, Del Porto JA, Miguel EC. Update on neurosurgical treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 26(1), 62–66 (2004).

- Greenberg BD, Rauch SL, Haber SN. Invasive circuitry-based neurotherapeutics: stereotactic ablation and deep brain stimulation for OCD. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(1), 317–336 (2010).

- Leiphart JW, Valone FH 3rd. Stereotactic lesions for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. J. Neurosurg. 113(6), 1204–1211 (2010).

- Bourne SK, Eckhardt CA, Sheth SA, Eskandar EN. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation for obsessive compulsive disorder: effects upon cells and circuits. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 6, 29 (2012).

- Blomstedt P, Sjöberg RL, Hansson M, Bodlund O, Hariz MI. Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. World Neurosurg. (2012).

- Bhattacharyya S, Chakraborty K. Glutamatergic dysfunction – newer targets for anti-obsessional drugs. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2(1), 47–55 (2007).

- Goddard AW, Shekhar A, Whiteman AF, McDougle CJ. Serotoninergic mechanisms in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Drug Discov. Today 13(7–8), 325–332 (2008).

- Fontenelle LF, Guimarães Barbosa I, Victor Luna J, Pessoa Rocha N, Silva Miranda A, Lucio Teixeira A. Neurotrophic factors in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 199(3), 195–200 (2012).

- Schmidt HD, Duman RS. Peripheral BDNF produces antidepressant-like effects in cellular and behavioral models. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(12), 2378–2391 (2010).

Website

- NICE. CG31 Obsessive–compulsive disorder: NICE guideline [Internet]. http://publications.nice.org.uk/obsessive–compulsive-disorder-cg31

Augmentation strategies in obsessive–compulsive disorder

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 70% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association's Physician's Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. Your patient is an 11-year-old boy with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) treated with multiple selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), but with poor response. Based on the review by Drs. Sundar and Reddy, which of the following statements about use of antipsychotics as augmentation strategies is most likely correct?

□ A There is little evidence to support antipsychotic augmentation

□ B Haloperidol is the antipsychotic with the best evidence supporting its use in augmentation

□ C Higher doses of antipsychotics are more effective as augmentation in OCD

□ D There is evidence to support the use of risperidone and aripiprazole

2. Based on the review by Drs. Sundar and Reddy, which of the following statements about use of other pharmacotherapy as augmentation strategies for the patient described in question 1 is most likely correct?

□ A Lithium, buspirone, clonazepam, and other traditionally recommended augmenting agents have been proven effective

□ B Clomipramine augmentation may be useful in patients not tolerating higher doses of other SSRIs

□ C Several large, randomized controlled trials have proven the efficacy of glutamatergic antagonists

□ D There is no evidence supporting the use of ondansetron, memantine, or riluzole

3. Based on the review by Drs. Sundar and Reddy, which of the following statements about use of nonpharmacological therapies as augmentation strategies in patients with OCD would most likely be correct?

□ A Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) should be used only as a last resort

□ B Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation should be used over temporal regions

□ C There is no role for ablative neurosurgery

□ D Deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be tried in carefully selected treatment-refractory patients