Abstract

Major depression is highly prevalent, and is associated with high societal costs and individual suffering. Evidence-based psychological treatments obtain good results, but access to these treatments is limited. One way to solve this problem is to provide internet-based psychological treatments, for example, with therapist support via email. During the last decade, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) has been tested in a series of controlled trials. However, the ICBT interventions are delivered with different levels of contact with a clinician, ranging from nonexisting to a thorough pretreatment assessment in addition to continuous support during treatment. In this review, the authors have found an evidence for a strong correlation between the degree of support and outcome. The authors have also reviewed how treatment content in ICBT varies among treatments, and how various therapist factors may influence outcome. Future possible applications of ICBT for depression and future research needs are also discussed.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 2 August 2012; Expiration date: 2 August 2013

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Describe the overall effect of ICBT for depression

• Describe the importance of guidance to outcomes of ICBT

• Describe the effect of treatment content and other variables on outcomes of ICBT

Financial & competing interests disclosure

PUBLISHER

Elisa Manzotti

Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK.

Disclosure: Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Laurie Barclay

Freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC.

Disclosure: Laurie Barclay, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS AND CREDENTIALS

Robert Johansson, MSc

Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden.

Disclosure: Robert Johansson, MSc, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Gerhard Andersson, PhD

Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden; Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry Section, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

Disclosure: Gerhard Andersson, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: This paper was sponsored in part by the Swedish research council and Linköping University (Professor contract).

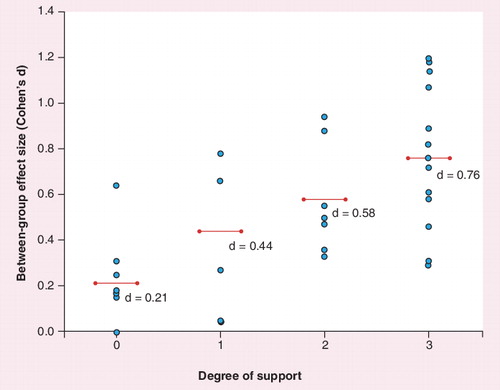

The degrees of support are defined as follows: 0, no therapist contact either before nor during treatment; 1, contact before treatment only; 2, contact during treatment only; and 3, contact both before and during treatment. The large dots represent effect sizes (Cohen’s d) between internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy conditions and controls. The horizontal lines between the smaller dots lines represent the average effect size per category of degree of support.

Major depression is a worldwide health problem, which lowers the quality of life for the individual and generates huge costs for society Citation[1,2]. In a 2003 survey, approximately half of the 12-month cases in the USA were receiving treatment for depression, and only 18–25% were adequately treated Citation[3]. Several forms of psychotherapy have been found to be effective in the treatment of depression Citation[4], and treatments that are structured follow a treatment manual and are time limited and in general equally effective in the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression. Such treatments include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral activation, interpersonal psychotherapy, short-term psychodynamic therapy and problem-solving therapy. These structured psychological treatments seem to work better than unstructured, nondirective therapeutic approaches Citation[5]. CBT has a strong empirical base for depression Citation[4], with the largest number of controlled trials among different psychotherapies. In short, CBT is an umbrella term for various treatments using cognitive and behavioral techniques.

CBT has been found to be transferable to the internet format, especially in the form of guided self-help Citation[6]. Guided self-help is a format of treatment delivery that presents structured self-help materials (e.g., via the internet) together with therapist contact (e.g., by email). The role of the therapist is to provide support, encouragement and occasionally direct therapeutic activities Citation[6].

In 2006, a summary of current research on internet-based CBT (ICBT) for depression was published Citation[7]. The field was quite new then, but the results were regarded as promising. By then, only five controlled ICBT studies existed that had targeted depression. Hence, no firm conclusions could be drawn regarding the overall efficacy and whether therapist support was crucial. Since then, the field has evolved very rapidly and the need for an update of the previous review is evident. The aim of this review is to provide an updated summary of research on ICBT for depression. The authors have focused on four main issues in this paper: the overall effect of ICBT for depression, the role of support in ICBT, how treatment content varies in ICBT and the role of the therapist. The authors conclude by discussing future research needs and further topics concerning ICBT for depression.

The overall effect of ICBT for depression

Initially, the authors provide a summary of a selection of previous reviews. In a meta-analysis from 2009, the overall effect of internet-based and computerized treatments for depression was investigated Citation[8], but not restricted only to ICBT even if the majority of studies can be categorized as ICBT. The authors included 15 comparisons and found that the overall effect size (Cohen’s d) was d = 0.41 (95% CI: 0.29–0.54). Importantly, this effect size was significantly moderated by a difference between guided (d = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.45–0.77) and unguided (d = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.14–0.35) treatments. This result was mirrored by a meta-analysis on self-guided psychological treatments (not necessarily internet based or computer based) Citation[9], which found an overall effect size of d = 0.28 (95% CI: 0.14–0.42). Another meta-analysis, which focused on ICBT for both depression and anxiety disorders, found an overall effect size (Hedges’s g) of g = 0.78 for the depression studies Citation[10]. These average effect sizes indicate that guided ICBT for depression may be on a par with face-to-face treatment. This claim was also supported by a meta-analysis on ICBT and guided self-help treatments for depression and anxiety disorders Citation[11]. In this analysis, 21 randomized controlled trials were included, in which participants were randomized to either guided self-help or face-to-face treatment. The overall between-group effect size was d = -0.03, indicating no difference between internet-based and face-to-face treatments in general. In summary, there is mounting support for a difference between guided and unguided ICBT, but no evidence for a difference between guided ICBT and face-to-face therapy.

The present review

The authors were able to include data from a total of 25 controlled trials. In eight of these trials, more than one treatment was compared with a control condition, resulting in a total of 33 comparisons with a control (such as waiting list or care as usual). The studies included were located via Medline, reference lists and a search for ongoing studies conducted by active researchers in the field. An overview of the located studies is given in . As seen in the table, effect sizes range between 0.10 and 1.20. As the aim of this report was not to conduct a formal meta-analysis, the mean effect size is not reported. While three studies formally contained other treatments than CBT (problem-solving therapy Citation[12,13] and psychoeduction Citation[14]), they were regarded as relevant for the review.

How important is guidance in guided ICBT?

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, there is evidence that guided ICBT is more effective than unguided, but the question is debated as unguided treatments cost less and can reach more people, whereas guided treatments appear to be more effective but have a narrower target group. There are also some inconsistencies on how guidance has been defined. Traditionally, guidance or support is provided during treatment. It is, however, unknown how contact before or after treatment affects the outcome Citation[15]. In this review, the included published studies were categorized according to the type of support provided. By support, the authors mean contact with a human and not an automated system that may handle screening, measures and automated reminders. The degree of support was designed as 0 when there was no human contact before, during or after the treatment period. Category 1 was assigned when there was contact only before the treatment. Category 2 was coded when there was contact mainly during the treatment. Finally, the degree of support was defined as 3 when there was a contact with the research staff or clinicians before, during and after the treatment period.

As indicated in , the between-group effect sizes vary depending on the degree of support. The average effect sizes for the respective categories were d = 0.21, 0.44, 0.58 and 0.76. A Spearman correlation of ρ = 0.64 (p < 0.01) was obtained between degree of support and effect size, indicating that more support yields larger effects. In , all 33 comparisons to a control condition are illustrated. However, as two effect sizes overlap in the figure, only 31 comparisons are visible.

This opens up more fine-grained differences between ICBT treatments for speculation. For example, two recent studies on unguided treatments showed medium-to-large effects when including a contact by telephone before treatment Citation[16,17]. In one case, these telephone contacts were a structured diagnostic interview and in the other an eligibility screening, but in both studies it was provided by trained staff. However, this is in contrast to two previous studies on unguided treatment, where face-to-face contact was provided before treatment. These studies had low Citation[18] or close to nonexisting effects compared with a control condition Citation[19].

indicates that a pretreatment contact could enhance guided treatments, which do not have a telephone or face-to-face contact before treatment. This pretreatment contact is often in the form of a structured diagnostic interview Citation[20,21], and probably results in more reliable diagnostic categories for inclusion in a trial. However, no trial exists in which this condition is directly manipulated. Future studies could use meta-analytical tools to explore how pretreatment contact including structured diagnostic procedures moderates treatment outcome.

The effect of pretreatment contact in unguided and guided internet-based treatments is a topic for further research. An exploration of this issue will also open up questions concerning the nature of such contacts. For example, it is unclear whether contacts that focus on motivation to complete the treatment will be more effective than other contacts in the treatment of depression Citation[22]. In addition, reliable diagnostic procedures may also enhance overall treatment effects, for example, by ensuring that the patients included in the treatment present with problems, that the treatment is intended to treat.

The effect of a clear deadline is related to the effect of pretreatment contacts. This has not been tested explicitly in ICBT for depression, but there is some evidence from bibliotherapy on panic disorder. In a study, 40 patients diagnosed with panic disorder were randomized to self-help treatment with a clear deadline or to a waiting list Citation[15]. After 10 weeks, all patients completed a telephone interview, which had been scheduled when the treatment started. The treatment had an average effect size of d = 1.0, indicating that the treatment was highly effective and that a clear deadline scheduled in advance was enough to motivate the participants to complete the treatment on their own. How this could be generalized to ICBT for depression is a topic for future research.

In conclusion, there is now a strong support for the claim that guided internet-based psychological treatments are more effective than unguided treatments. The categorization of studies after degree of support indicates that the effect of guidance may be moderated by whether pretreatment contact is available. Further exploration of these moderators is a topic for future meta-analyses.

Does treatment content in ICBT matter?

With a few exceptions, all published studies considered in this review have been based on CBT. One Australian study Citation[14] included a psychoeducational intervention and two studies from The Netherlands tested the efficacy of an internet-based problem-solving therapy Citation[12,13]. Both these treatments seem to be comparable in efficacy to CBT Citation[13,14]. These results are mirrored by the fact that there are few indications of differences in efficacy between various face-to-face psychological treatments for depression Citation[4]. This also indicates that psychological treatments other than CBT may be possible to deliver via the internet. For example, the authors’ research group has recently completed a trial on internet-based psychodynamic treatment for depression where the between-group effect size, compared with an active control, was d = 1.11 (95% CI: 0.67–1.56). In this study, the active control condition consisted of psychoeducation and weekly support contacts online. These studies suggest that psychological treatments other than CBT can be delivered through the internet and open up a mixture of various treatment approaches, for example, by including treatment components from non-CBT treatments within a CBT framework. Deprexis, the treatment tested by Meyer et al. Citation[23] and Berger et al. Citation[16], is an example of such a blend as it includes positive psychology interventions, dreamwork and emotion-focused interventions above more traditional cognitive and behavioral techniques. Future studies evaluating such component-based treatments could include process measures to investigate the specific effects of various components.

As pointed out earlier, the amount of guidance varies between treatments (i.e., guided vs unguided treatments). Besides, the treatments investigated also vary in scope (e.g., if the treatment specifically targets depression or has a general scope to also target for example, comorbid anxiety disorders), which phase of depression treatment is in focus (e.g., treatment in the acute phase or relapse prevention after recovery), and if the treatment is given as a standalone treatment or is given as a complement to regular care.

Recently, there have been examples of treatments targeting a broader scope than depression. An Australian team has explored a transdiagnostic ICBT intervention in the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders Citation[24]. This treatment appears to be effective both in the treatment of depression and anxiety. A transdiagnostic treatment conceptualizes a psychological problem in general terms and provides general treatment ingredients, assumed to be able to target multiple conditions. The primary benefit of this kind of ‘one size fits all’ treatment is that it makes the procedure of treatment selection less demanding. This may, for example, be of benefit in treatment contexts where time and/or competence for thorough assessment is missing, for example, in primary care.

In Sweden, there are recent examples of individually tailored ICBT treatments for depression and anxiety disorders Citation[25,26]. Instead of providing the same material to all participants, a treatment package is tailored from a pool of different treatment modules. For example, a patient with a diagnosis of depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) may receive a treatment based on behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring and interventions targeting worry (e.g., worry time and exposure to worry). Recent results exist proving the efficacy compared with control for mixed anxiety Citation[25,27] and in the treatment of depression with a high amount of comorbid anxiety Citation[26]. The study by Johansson et al. included a comparison between tailored and nontailored treatment for depression and provided data that indicate that tailored treatment is superior to nontailored treatment for patients with more severe forms of depression Citation[26]. This study is one of the few that provides some indications of differential efficacy between active treatments.

Instead of providing ICBT as a standalone treatment, there are examples of studies investigating the efficacy of ICBT added to care as usual (CAU). One example is a large primary care study from the UK where real-time online CBT was added to CAU Citation[28]. The CBT plus CAU intervention outperformed CAU alone, measured by the amount of patients who recovered from depression. This study is an example of how ICBT can enhance regular treatment in terms of efficacy. In another study, adding ICBT to CAU did not improve the outcome Citation[19]. However, despite similar delivery context and study design, there are important differences between the therapist-supported intervention in the study by Kessler et al. Citation[28] and the nonguided intervention in the study by de Graaf et al. Citation[19].

The majority of ICBT treatments for depression have been conducted on depression in the acute phase. One exception is that the treatment developed by Holländare et al., where people suffering from partially remitted depression after previous treatment were randomized to ICBT or to a control condition Citation[29]. Significantly, fewer participants receiving ICBT experienced relapse compared with those in the control group (10.5 compared with 37.8%), which is in line with previous face-to-face studies Citation[30].

Recently, there have been examples on how ICBT has been adapted for depression in specific populations. A study from The Netherlands tested ICBT for depression in a population with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic patients with depressive symptoms Citation[31]. The ICBT intervention had a small to medium effect on depressive symptoms, which was the primary outcome. Another recent attempt to reach out to specific populations is the study by Smith et al., in which an internet-based psychoeducational intervention was tested for patients with bipolar disorder Citation[32]. In the study, there were no significant differences on any of the outcome measures between the intervention and the control group. However, there was a difference in a subscale measuring psychological quality of life. Despite few differences between treatment and control, this study represents a proof-of-concept that it is possible to deliver an ICBT intervention to patients with bipolar disorder. Finally, there is an Australian study on a culturally attuned ICBT intervention for depressed Chinese Australians Citation[33]. The program was translated to Mandarin/Cantonese and had the content culturally adapted, in terms of text and exercises. On average, the between-group effect for the ICBT intervention compared with control was medium-to-large.

In summary, as the field of ICBT treatments for depression expands rapidly, examples of other treatment approaches than CBT have begun to emerge. With the exception of study by Johansson et al., no study exists where differences in efficacy between ICBT treatments are observed Citation[26]. Differences in working mechanisms and efficacy are topics for future research. As depression continues to be a worldwide health problem, ICBT has proven to be a way to reach out to new populations.

Is it important who the therapist is & what the therapist does?

Despite many new studies on ICBT for depression, including meta-analyses proving the importance of guidance, little is known about the role of therapist factors in internet-based treatments. Two Swedish studies exist that have specifically investigated the therapist effect in ICBT for depression and anxiety disorders, respectively Citation[34,35]. In these studies, the patients’ measurements were modeled to be clustered within a specific therapist. Using these two-level models, the therapist effects were measured by the intraclass correlation, which is a measure of the variability due to the clustering. Small intraclass correlations are found on some measures, indicating nonexisting or small therapist effects in ICBT Citation[34,35].

Another way of studying therapist effects in ICBT is to search for specific therapist behaviors in text conversations. This was done in a recent study on ICBT for GAD Citation[36]. Results showed that therapist behavior, such as deadline flexibility, was negatively correlated to change scores on the main outcome measure. Further results showed that behaviors, such as task reinforcement, task prompting and making empathic utterances, were all correlated with module completion Citation[36]. This study opens the way for microanalyses of therapist behavior in ICBT, which may enhance ICBT for depression and other conditions.

Three Australian studies on ICBT, for depression, social anxiety disorder and GAD, compared treatment outcome when the therapist was either a psychologist or a computer technician Citation[37–39]. While each study only had one therapist and one technician, the data give no support for differences in treatment outcome between therapists in ICBT.

One factor that is known to vary between therapists is therapeutic alliance. A recent study explored alliance in ICBT and face-to-face therapy for depression Citation[40]. While alliance was present and comparable in the two groups, it could not predict treatment outcome in any of the two treatment groups. This is mirrored in the study by Knaevelsrud and Maercker, in which therapeutic alliance was found important in ICBT for post-traumatic stress disorder Citation[41]. However, while the authors found high patient ratings of alliance, associations with treatment outcome were modest. This finding mirrors unpublished data from the authors’ research group on alliance in ICBT. Although high alliance ratings have been found in the trials, we cannot predict treatment outcome using alliance ratings.

In summary, little is known about the role of therapist factors in ICBT. The Australian studies indicate that it is possible to specify the therapist behavior as certain ‘roles’, which even nonclinical staff can adhere to. Studies on therapeutic microprocesses may reveal effective and ineffective therapist behavior, and the importance of adequate self-help texts should also be investigated Citation[42].

Expert commentary & five-year view

Major depression is a worldwide health problem for which cost-effective interventions are needed. Recent reviews conclude that internet-based psychological treatments are important treatment alternatives that can be as effective as face-to-face CBT. This review has explored how contact before and after treatment may moderate treatment outcomes in both unguided and guided ICBT. Future controlled trials and meta-analytic reviews should investigate the specific effect of this kind of support. As ICBT begins to reach out to healthcare providers, for example, primary care, where time may be very limited, more detailed knowledge about the role of therapist contact is needed. For example, an unguided self-help program with a thorough assessment and clear deadline may be easier to implement in primary care than a treatment that requires continuous therapist support. As pretreatment interviews often involve diagnostic procedures, the time invested could also prevent prescribing ICBT to patients who drop out immediately or receive a treatment that does not suit their problem profile.

Future research should explore how to make guided and unguided ICBT even more effective. It is reasonable to believe that ICBT could be enhanced if integrated with day-to-day technology, such as modern mobile telephones (smartphones). For example, a technique such as activity scheduling seems optimal for using a smartphone with automatic reminders. ICBT may be further enhanced by integrating more recently developed technology from computer science, such as the field of artificial intelligence. This kind of technology could be used for automatic feedback, intelligent adaption and tailoring of treatment material, among other things. Using modern technology, it is not unreasonable to believe that unguided ICBT could be as effective as guided ICBT. Moreover, not all patients require much support, and the dissemination of ICBT would be helped by systems that could identify when human support is needed to prevent treatment failure.

Table 1. Overview of controlled trials of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression.

Key issues

• Internet-based psychological treatments are effective and provide an important treatment alternative to face-to-face psychological treatments and medication.

• Guided internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) treatments are more effective than unguided ICBT.

• Contact before and/or after the treatment may potentially enhance both guided and unguided ICBT.

• Unified and tailored ICBT approaches provide a promising treatment development that may broaden the scope of ICBT.

• Little is known about the therapist factor in ICBT. There are some indications that nonclinicians may be able to provide ICBT.

• Modern technology, such as smartphones and artificial intelligence, may potentially enhance ICBT.

References

- Ebmeier KP, Donaghey C, Steele JD. Recent developments and current controversies in depression. Lancet 367(9505), 153–167 (2006).

- Smit F, Cuijpers P, Oostenbrink J, Batelaan N, de Graaf R, Beekman A. Costs of nine common mental disorders: implications for curative and preventive psychiatry. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 9(4), 193–200 (2006).

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al.; National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289(23), 3095–3105 (2003).

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, van Oppen P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76(6), 909–922 (2008).

- Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD, van Oppen P, Barth J, Andersson G. The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32(4), 280–291 (2012).

- Andersson G. Using the Internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 47(3), 175–180 (2009).

- Andersson G. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral self help for depression. Expert Rev. Neurother. 6(11), 1637–1642 (2006).

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 38(4), 196–205 (2009).

- Cuijpers P, Donker T, Johansson R, Mohr DC, van Straten A, Andersson G. Self-guided psychological treatment for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 6(6), e21274 (2011).

- Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 5(10), e13196 (2010).

- Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, Li J, Andersson G. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol. Med. 40(12), 1943–1957 (2010).

- van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N. Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 10(1), e7 (2008).

- Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, Riper H, Cuijpers P. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 10(4), e44 (2008).

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 328(7434), 265 (2004).

- Nordin S, Carlbring P, Cuijpers P, Andersson G. Expanding the limits of bibliotherapy for panic disorder: randomized trial of self-help without support but with a clear deadline. Behav. Ther. 41(3), 267–276 (2010).

- Berger T, Hämmerli K, Gubser N, Andersson G, Caspar F. Internet-based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 40(4), 251–266 (2011).

- Farrer L, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A. Internet-based CBT for depression with and without telephone tracking in a national helpline: randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 6(11), e28099 (2011).

- Spek V, Nyklícek I, Smits N et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression in people over 50 years old: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychol. Med. 37(12), 1797–1806 (2007).

- de Graaf LE, Gerhards SA, Arntz A et al. Clinical effectiveness of online computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy without support for depression in primary care: randomised trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 195(1), 73–80 (2009).

- Perini S, Titov N, Andrews G. Clinician-assisted internet-based treatment is effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 43(6), 571–578 (2009).

- Vernmark K, Lenndin J, Bjärehed J et al. Internet administered guided self-help versus individualized e-mail therapy: a randomized trial of two versions of CBT for major depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 48(5), 368–376 (2010).

- Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, Robinson E, Peters L, Spence J. Randomized controlled trial of Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for social phobia with and without motivational enhancement strategies. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 44(10), 938–945 (2010).

- Meyer B, Berger T, Caspar F, Beevers CG, Andersson G, Weiss M. Effectiveness of a novel integrative online treatment for depression (Deprexis): randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 11(2), e15 (2009).

- Titov N, Dear BF, Schwencke G et al. Transdiagnostic internet treatment for anxiety and depression: a randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 49(8), 441–452 (2011).

- Carlbring P, Maurin L, Törngren C et al. Individually-tailored, Internet-based treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 49(1), 18–24 (2011).

- Johansson R, Sjöberg E, Sjögren M et al. Tailored vs. standardized internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression and comorbid symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 7(5), e36905 (2012).

- Silfvernagel K, Carlbring P, Kabo J et al. Individually tailored internet-based treatment of young adults and adults with panic symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 14(3):e65. (2012).

- Kessler D, Lewis G, Kaur S et al. Therapist-delivered internet psychotherapy for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374(9690), 628–634 (2009).

- Holländare F, Johnsson S, Randestad M et al. Randomized trial of internet-based relapse prevention for partially remitted depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 124(4), 285–294 (2011).

- Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Dunn TW, Jarrett RB. Reducing relapse and recurrence in unipolar depression: a comparative meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effects. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75(3), 475–488 (2007).

- van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Snoek FJ. Web-based depression treatment for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 34(2), 320–325 (2011).

- Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Poole R et al. Beating Bipolar: exploratory trial of a novel Internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 13(5–6), 571–577 (2011).

- Choi I, Zou J, Titov N et al. Culturally attuned Internet treatment for depression amongst Chinese Australians: a randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 136(3), 459–468 (2012).

- Almlöv J, Carlbring P, Berger T, Cuijpers P, Andersson G. Therapist factors in internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for major depressive disorder. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 38(4), 247–254 (2009).

- Almlöv J, Carlbring P, Källqvist K, Paxling B, Cuijpers P, Andersson G. Therapist effects in guided internet-delivered CBT for anxiety disorders. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 39(3), 311–322 (2011).

- Paxling B, Lundgren S, Norman A et al. Therapist behaviours in internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy – analyses of e-mail correspondence in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. doi:10.1017/S1352465812000240 (2012) (Epub ahead of print).

- Titov N, Andrews G, Davies M, McIntyre K, Robinson E, Solley K. Internet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS ONE 5(6), e10939 (2010).

- Robinson E, Titov N, Andrews G, Mcintyre K, Schwencke G, Solley K. Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS ONE 5(6), e10942 (2010).

- Titov N, Andrews G, Schwencke G, Solley K, Johnston L, Robinson E. An RCT comparing two types of support on severity of symptoms for people completing internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for social phobia. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry 43(10), 920–926 (2009).

- Preschl B, Maercker A, Wagner B. The working alliance in a randomized controlled trial comparing online with face-to-face cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. BMC Psychiatry 11, 189 (2011).

- Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 7, 13 (2007).

- Richardson R, Richards DA, Barkham M. Self-help books for people with depression: the role of the therapeutic relationship. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 38(1), 67–81 (2010).

- Andersson G, Bergström J, Holländare F, Carlbring P, Kaldo V, Ekselius L. Internet-based self-help for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 187, 456–461 (2005).

- Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O’Kearney R. The YouthMood Project: a cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 77(6), 1021–1032 (2009).

- Clarke G, Reid E, Eubanks D et al. Overcoming depression on the Internet (ODIN): a randomized controlled trial of an Internet depression skills intervention program. J. Med. Internet Res. 4(3), E14 (2002).

- Clarke G, Eubanks D, Reid E et al. Overcoming Depression on the Internet (ODIN) (2): a randomized trial of a self-help depression skills program with reminders. J. Med. Internet Res. 7(2), e16 (2005).

- Clarke G, Kelleher C, Hornbrook M, Debar L, Dickerson J, Gullion C. Randomized effectiveness trial of an Internet, pure self-help, cognitive behavioral intervention for depressive symptoms in young adults. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 38(4), 222–234 (2009).

- O’Kearney R, Gibson M, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Effects of a cognitive-behavioural internet program on depression, vulnerability to depression and stigma in adolescent males: a school-based controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 35(1), 43–54 (2006).

- O’Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K. A controlled trial of a school-based internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress. Anxiety 26(1), 65–72 (2009).

- Ruwaard J, Schrieken B, Schrijver M et al. Standardized web-based cognitive behavioural therapy of mild to moderate depression: a randomized controlled trial with a long-term follow-up. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 38(4), 206–221 (2009).

Internet-based psychological treatments for depression

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 70% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. Based on the review by Drs. Johansson and Andersson, which of the following statements about the overall effect of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) for depression is most likely correct?

□ A ICBT is significantly less effective for depression than face-to-face treatments

□ B ICBT is as effective as face-to-face treatments for anxiety

□ C For depression, ICBT provides an important treatment alternative to face-to-face psychological treatments and medication

□ D Most internet-based therapy involves problem-solving therapy

2. Your patient is a 48-year-old woman with depression. Based on the review by Drs. Johansson and Andersson, which of the following statements about the importance of guidance to outcomes of ICBT is most likely correct?

□ A Guided and unguided ICBT treatments are about equally effective

□ B Contact before and/or after ICBT does not affect the efficacy of guided or unguided ICBT

□ C Degree of human support was significantly correlated with effect size

□ D The specific focus of the human contact does not appear to affect ICBT efficacy

3. Based on the review by Drs. Johansson and Andersson, which of the following statements about the effect of treatment content and other variables on outcomes of ICBT for the patient described in question 2 would most likely be correct?

□ A Studies have shown that efficacy of ICBT is best when it is performed by a therapist

□ B Smartphones, artificial intelligence, and other modern technology methods may potentially enhance ICBT

□ C Therapeutic alliance is a significant, dramatic predictor of treatment outcome in ICBT

□ D All studies have shown that tailored ICBT is superior to non-tailored ICBT regardless of depression severity