Abstract

Community services comprise an important part of a country’s HIV response. English language cost and cost–effectiveness studies of HIV community services published between 1986 and 2011 were reviewed but only 74 suitable studies were identified, 66% of which were performed in five countries. Mean study scores by continent varied from 42 to 69% of the maximum score, reflecting variation in topics covered and the quality of coverage: 38% of studies covered key and 11% other vulnerable populations – a country’s response is most effective and efficient if these populations are identified given they are key to a successful response. Unit costs were estimated using different costing methods and outcomes. Community services will need to routinely collect and analyze information on their use, cost, outcome and impact using standardized costing methods and outcomes. Cost estimates need to be disaggregated into relevant cost items and stratified by severity and existing comorbidities. Expenditure tracking and costing of services are complementary aspects of the health sector ‘resource cycle’ that feed into a country’s investment framework and the development and implementation of national strategic plans.

Data taken from Citation[101].

![Figure 1. Annual international and domestic HIV expenditure 2002–2011.Data taken from Citation[101].](/cms/asset/94317d5c-8238-440f-8c83-b585b248e668/ierp_a_11215641_f0001_b.jpg)

The number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) was 34 million at the end of 2011 and is set to increase Citation[101]. This is due to increased survival of PLHIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART), while the number of people newly infected continue to exceed those put on ART Citation[101]. At the end of 2011, 8 million PLHIV in resource limited countries were on ART Citation[102], most of whom now attain near-normal life expectancies Citation[1,2]. While costs for prevention and treatment services in resource-limited countries have decreased over time, largely due to reductions in drug costs Citation[3], the increasing number of PLHIV requiring HIV treatment and care services will increase population costs Citation[4]. Prevention services in many countries will also need to be scaled up, including biomedical, behavioral and structural interventions Citation[5], all of which are likely to increase costs in the short term.

Increased life expectancy due to long-term ART will also increase the number of ‘older’ PLHIV aged 50 years or older. Older PLHIV are at an increased risk of developing other non-HIV diseases Citation[6–8], especially cardiovascular disease, non-AIDS related cancers, neurological complications, liver and renal problems, bone abnormalities and ‘frailty’ Citation[9,10]. In addition to providing HIV-specific services for PLHIV, their HIV management will need to be integrated with antenatal, pediatric and other specialist services including general geriatric services Citation[11].

While the international component of global HIV funding has plateaued since 2008, overall annual global funding has, however, continued to rise due to increased financial contributions by some middle-income countries. They are funding their own HIV response within the spirit of the African Union’s Roadmap on Shared Responsibility and Global Solidarity Citation[103]. For countries to be able to provide optimal services or programs within tightening budgets, policy-makers need strategic information to ensure that their response is as effective, efficient, equitable and as acceptable as possible Citation[12,13]. This requires robust and contemporary information on the use, cost, outcome and impact of prevention, treatment and care services. Information on the cost of programs or services and their efficiency constitute important aspects of such strategic information Citation[12,13].

Reviews of facility-based costs studies and cost–effectiveness studies, however, indicated profound limitations of published cost information Citation[3,14,15]. Problems identified included lack of standardized methods used for costing services, affecting the robustness of the analyses and the results obtained, raising serious questions on the quality of many of the reported findings. Publishing costing studies enables methods and results to be reviewed by stakeholders within a country or region in which they were performed Citation[3]. In addition, publication allows the robustness of the studies to be reviewed and these processes can facilitate the implementation of standardized costing methods in countries.

While in many countries, statutory prevention, treatment and care services are provided through health facilities – including primary care clinics, secondary, tertiary or quaternary hospitals – community involvement has and continues to play an important part in the HIV response of many countries Citation[16]. This can involve both statutory and informal community-based services, including outreach, community mobilization and community-based treatment and care services Citation[16]. It has been argued that involving communities directly with healthcare and other social and economic issues is an important aspect of improving conditions in these communities Citation[17]. ‘Community’ is this context is defined as groups that have a shared cultural identity, where members belong to a group that shares common characteristics or interests, or a shared geographic place, where members live or work in a physical location or an administrative entity Citation[16]. Recognizing that community services are an integral part of any national HIV response, strategic information on the performance of these services or programs are required by policy-makers. To evaluate the extent that such information is available, a review of the quantity and quality of published studies on the cost or cost–effectiveness of community services or programs was performed. Cost–effectiveness studies were also included in order to assess the cost and outcome data used in these analyses.

Methods

Methods used for this review were similar to those used in previous reviews of published facility-based costing studies Citation[3,14] and cost–effectiveness studies Citation[15]. Articles published between 1986 and 2011 on the costs of community-based services associated with HIV interventions were identified by searching the following electronic databases: Medline, Embase, CABI Global Health database, POPLINE, Cochrane library and the WHO regional databases (Africa, eastern Mediterranean, Latin America and the Caribbean, Pan American Health Organization Library and Institutional Memory database, south-east Asia, western Pacific, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences). Searches were limited to articles published in English with references from primary articles and reviews added where relevant. The search strategy combined the keywords ‘HIV’ or ‘AIDS’ and ‘cost’ or ‘cost analysis’ or ‘healthcare cost’ and ‘community’ or ‘voluntary care’ or ‘home-based care’. Multiple keyword sets were used to broaden the search and increase sensitivity and more than 3000 articles were identified.

Abstracts of these articles were reviewed to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. Studies were included if they reported on HIV preventive or therapeutic interventions at the community level, were published in a peer-reviewed journal and provided cost data either as a cost per service or outcome or cost per patient-period. Community-level services included outreach services, primary or community or mobile clinics, home visits and home-based care. Modeling studies were also included if the sources of utilization and cost data were reported in the article. Articles that considered the cost of treating AIDS-related illnesses or other opportunistic infections were excluded. Articles that assessed general community-based services without specific costs attributed to HIV interventions were also excluded. Subsequently, the full text articles were screened for further eligibility criteria for inclusion in this analysis.

All articles that met the inclusion criteria were analyzed using an analytic framework and scored based on a set of 25 criteria with a maximum possible score of 85. The criteria included in this analysis were adapted from an analytic framework developed to review the costs of facility-based care for HIV published between 1998 and 2008 Citation[3]. These criteria were modified to reflect additional information related to the type and setting of community-based service reported, type of cost and utilization data and degree of detail of costs reported for each study.

Two reviewers (O Fasawe and P Ongpin) examined and scored the full-text articles using the analytic framework . Where the scores varied by more than five points, the article was re-examined by a third reviewer (EJ Beck) and following a discussion between all three reviewers, a consensus score was adopted. The score for each of the reviewed studies is cited in the reference list Citation[18–91].

Information was extracted from studies and classified by type of community-based service provided, by country, region, year of publication and Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) country classification. Costs and efficiency data were reported only for HIV-related programs. All costs were inflated to the 2010 equivalent using country-specific inflation rates available from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund databases Citation[104,105]. The costs were then converted from local currency values to the US dollar value using 2010 purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted exchange rates, where available Citation[104,105]. Costs per outcome or per patient-period were reported and where costs were reported per day or per month, these were adjusted to determine the cost per patient-year for ease of comparison. Summary tables of the nine types of community services identified were produced by country and OECD regions . Averages across the costs estimates provided by the studies were not produced given the great diversity between services studies, in terms of cost items included, costing methods used and outcomes analyzed. Instead, summary ranges are presented of published unit costs of services or outcomes.

Results

Number of studies & country

Seventy four published studies performed in 23 countries were identified that complied with the study’s selection criteria and were published between 1 January 1986 and 31 December 2011: 33 (45%) were performed in sub-Saharan Africa, 25 (34%) in North America and the Caribbean, nine (12%) in Asia, while of the remaining seven studies, four were performed in Europe, two in Peru, South America and one in Australia . Nine (27%) of the sub-Saharan African studies were performed in South Africa, six (18%) in Uganda and five (15%) in Zambia: the remaining 13 studies were performed in eight countries. Of the 25 studies performed in North America, 23 were performed in the USA, six out of the nine Asian studies were performed in India and three of the four European studies were performed in England.

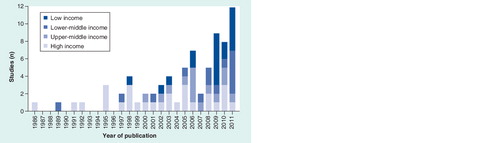

When analyzed by OECD country classification, the high-income countries (HICs) generated 28 (38%) studies, upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) 14 (19%), 13 (18%) in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and 19 (26%) in low-income countries (LICs) . During the study period, the number of cost studies published annually did increase significantly ; Spearman R72: 0.996; p < 0.01). While studies from HICs were published during most years, since 2002 the number of studies published from LICs increased considerably. Of the HICs studies, 23 (82%) were performed in the USA, nine (64%) studies performed in UMICs were performed in South Africa, while in the LMICs, six (46%) studies were performed in India and five (42%) in Zambia. Of the studies performed in LICs, six (26%) were performed in Uganda and three (16%) each in Kenya and Tanzania. Overall, 49 (66%) studies were performed in five countries: USA, South Africa, India, Uganda and Zambia, of which Uganda was the only LIC.

Of the 74 studies, 46 (62%) were cost studies and 28 (38%) were cost–effectiveness studies that had a cost component to them. The cost studies were relatively evenly distributed across all OECD category countries, with 13 (28%) studies performed in HICs and 11 (24%) in each of the other OECD country categories. A disparity was observed among the cost–effectiveness studies with 15 (54%) performed in HICs, eight (29%) in LICs and three (11%) and two (7%) in UMICs and LMICs, respectively.

Quality of studies: study scores

Based on the analytic framework , each study was scored. Individual study scores were aggregated and mean scores and ranges were produced by continent and OECD country categories . Mean scores by continent varied from 36 to 59, or 42–69% of the maximum score. The North American and Caribbean studies displayed the widest range, from 15 to 50, or 17–59% of the maximum score. In terms of OECD country categories, raw scores varied from 38 to 46, or 45–54% of the maximum score. The HICs had the greatest range, with scores varying between 14 and 61, or 17–72% of the maximum score.

Information covered by studies

Eighty percent of studies were performed at the subnational level . Many studies presented data on different combinations of services: 64% were outreach programs, 31% community clinic services, 20% home-based care and 15% of services involved community health workers. The healthcare system was the focus of analysis in 46% of studies, 45% costed specific programs, while 9% of studies had a societal focus. While 50% of the studies could be identified as publicly funded services, this was unclear for the remainder. Sixty five percent of studies targeted the general population, 38% key populations – men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSWs) and injecting drug users (IDUs) – and 11% other vulnerable populations including youth, women and prisoners. Fifty two percent of studies were set in an urban setting, 22% covered rural services, while for 26% of studies the geographical setting was either not mentioned or unclear. Ninety two percent used original service utilization data: 77% collected data longitudinally, 14% used cross-sectional data and one study used ‘expert opinion’. Utilization data were collected on more that 100 persons in 82% of the studies, with duration of follow-up more than 12 months in 41%; 27% of studies followed users of services between 6 and 12 months, whereas 19% of studies had periods of follow-up of 6 months or less.

Data collection methods varied, with a substantial number of studies using more than one method to collect their data. Fifty one percent of studies relied on obtaining data retrospectively from registries or databases, with a further 31% having monitored use of services prospectively. Data obtained directly from users of services included both client interviews performed in 20% of studies and the completion of questionnaires or diaries.

In terms of cost data, 49% claimed to have performed a costing exercise: among 41% the costing exercise involved multiple sites whereas for 8% this was performed in a single site. Cost components were not broken down in 15% of studies: staff costs were identified in 78%, overheads in 64%, capital costs in 55% and costs for tests and consumables like condoms in 47% of studies. Transportation costs were included in 39% of studies and drug costs in 28%. Out-of-pocket expenses were only included in 9% of the studies.

Of those studies that performed a costing exercise and identified their data source, 31% indicated that they used utilization and cost data from the same site whereas 14% used data that came from different sites. Eighty percent of studies did not disaggregate cost estimates by patient characteristics; only 7% of studies disaggregated costs by demographic characteristics of service users, 8% disaggregated costs by risk factors or severity of HIV infection, respectively, while in only 3% of studies costs were disaggregated by comorbid conditions or other measures of severity.

In terms of data analysis, 92% of studies provided point estimates for utilization data, with only 23% including some measure of variability. Similarly, while 96% of studies provided point estimates for the cost data, only 58% presented indicators of variability around these point estimates. Seventy seven percent of studies estimated a cost per visit or other outcome, while 32% reported a cost per specific time period. Thirty eight percent of studies analyzed their data using bivariate analyses or univariate modeling, while 24% did not perform any additional statistical analyses. Thirty five percent tested or adjusted their analyses for skewness, while 11% of studies used multivariate analyses.

Unit costs for HIV community services

Most published studies estimated costs for generic testing and counseling (T&C) or voluntary counseling and testing services (VCT) . Twenty one studies were identified across all OECD countries and the unit costs for the various services varied within and across countries and OECD regions. This variation was partly a function of the different outcome measures identified, as many were associated with different unit costs estimates. The efficiency studies also used different outcome measures and produced different unit costs again making comparisons tenuous. Given these caveats, unit costs ranged between US$14 and 18,740 for HICs, US$33–250 for UMICs, US$17–3545 for LMICs and US$4–647 for LICs . The cost–effectiveness studies for different outcomes in UMICs ranged from US$103 to 4129, and from US$301 to 4265 in LICs .

Outreach and community mobilization services were the second most numerous services studied. The 19 studies identified covered all OECD regions and included a number of cost–effectiveness studies . Again, considerable variation in terms of the services investigated was observed and included treatment, care and prevention services, resulting in a range of different outcome measures and associated unit costs . Variations were again observed within and between countries and OECD regions. Noting the stated caveats, unit costs ranged between US$8 and 328 for HICs, between US$181 and 187 for UMICs, between US$30 and 1748 for LMICs and between US$5 and 250 for LICs . Cost–effectiveness studies of these services were performed in HICs and UMICs, with results that ranged from US$12,274 to 49,429,105 and US$520 to 32,057, respectively .

The third most common service studied was community-based provision of ART : 17 studies could be identified and included adherence management services for people living with HIV on ART and studies on the cost of providing ART; studies were performed in all OECD countries except LMICs and included two cost–effectiveness studies . With similar caveats as expressed above, unit costs ranged between US$1935 and 5039 for HICs, between US$20 and 2981 for UMICs and between US$90 and 17,575 for LICs . Cost–effectiveness studies were performed in HIC and LICs and results were US$14,802 and US$717–2000, respectively .

Fifteen studies covered the provision of home-based services. Services costed included home visits, home-based services with and without ART costs while two cost–effectiveness studies were identified . Unit costs for HICs ranged between US$212 and 28,884, for UMICs between US$8 and 1806, and for LICs the unit cost was US$17,575 . Cost–effectiveness analysis of some of these services was performed in HICs and LICs and results were US$14,802 and US$1294–2000, respectively . Five studies covered condom services and all performed in HICs and LICs ; units cost in HICs ranged between US$5 and 277, while the unit cost estimate for the LIC study was US$5. The cost–effectiveness studies performed on these services ranged from US$24,921 to 874,050 in HICs and US$1914 per outcome for LICs .

Of the studies that specifically studied key populations, seven focused on MSM ; HICs unit costs ranged between US$8 and 1500, an unit cost of US$199 was estimated for UMICs, while for LMICs unit costs ranged between US$85 and 182. Cost–effectiveness studies were performed in HICs with a range of US$2539–23,643 for different outcomes . An additional seven studies could be identified on services for FSWs, with unit costs in UMICs and LMICs with a range of US$150–257 and US$17–194, respectively . Cost–effectiveness studies performed in UMICs and LICs estimated a range of US$170–32,056 and US$117–756, respectively . Only four published studies that covered services for IDUs could be identified; all were performed in HICs with unit costs ranging between US$23 and 665 . Services for MSM and FSWs included outreach, VCT and treatment and care services. It was of interest to note that no studies of MSM could be identified from LICs, while the studies identified on FSWs came from UMICs and LMICs only. Of the studies that covered transgender persons, the study performed in the HIC generated a unit cost between US$650 and 10,846, and the one performed in the LMIC estimated a unit cost of US$235 .

Discussion

For the period 1986–2011, only 74 published studies on the cost and cost–effectiveness of community services could be identified from 23 countries or 12% of the 196 currently recognized nation states Citation[106]. While there has been a significant increase in published studies over this time period, the number of published studies remain very few compared with the need that country policy-makers have for this type of information, especially since in many countries community-based programs have been an important part of their HIV response Citation[16]. Forty nine (66%) published studies were performed in five countries: the USA, South Africa, Uganda, India and Zambia. While most of the costing studies were performed equally across OECD countries, the cost–effectiveness studies were predominantly performed in HICs, especially the USA.

Mean study scores by continent varied from 42 to 69% of the maximum score of 85, indicating that the quality of the studies varied considerably and many studies were not of a very high standard. Most studies were focused on urban settings, many of which were outreach services often involving the general population with few studies focusing on key or other vulnerable populations. Most of the data were collected retrospectively, half of the studies claimed to have performed a costing exercise but many did not break down costs into relevant components and few analyses were disaggregated by characteristics of those using the services.

Generic community services were the most commonly costed services while relatively few studies covered services for key or vulnerable populations including MSM, FSWs, IDUs and transgender persons. Knowing the key populations involved in a country’s epidemic and directly involving them in terms of the country’s response remains a primary principle for any successful HIV response Citation[101]. Programs for these marginalized populations should improve access to services, reduce existing stigma and discrimination and lead to better health outcomes. It was therefore surprising that so few published studies could be identified on programs and services that serve these key populations.

While the majority of the studies broke down the costs into various cost items, often these were not comparable and consistent across the different studies. Different cadres of staff were often included and costs were not disaggregated. Similar interventions included different activities across the studies and shared resources among multiple interventions within the same program were not recognized and no studies explicitly dealt with shared resources. Of the studies identified, only two studies addressed the effect of scale Citation[32,66]. The Zambian study focused on scale in a particular geographic setting, whereas the Indian study investigated the variation in costs between inception of the program and 2 years of rapid scale-up. The latter demonstrated a reduction in costs when the program was scaled up but the full-extend of scaling up and the impact on costs were yet to be achieved Citation[32].

This review has a number of limitations. The number of different outcome measures identified for community services and their associated costs were even more numerous and divergent than those used for facility-based costing studies Citation[3,14]. Given the diversity of outcome measures and costing methods used, it was considered inappropriate to estimate average costs within and between countries. Ranges of unit cost estimates were cited but given the lack of standardized costing methods and outcomes used, many of them are not comparable and they have to be used with extreme caution. Furthermore, only studies published in English were included, and therefore any costing studies published in other languages will have been missed. The number of published studies is also likely to underestimate the actual number of costing studies performed, as many studies may be part of the unpublished ‘gray’ literature.

The importance of community services as part of a comprehensive country HIV response has been recognized for a long time Citation[16]. However, in some circumstances policy-makers have considered community services to provide a ‘cheaper option’ to facility-based services. This was highlighted during the 1980s and 1990s when the introduction of long-acting antipsychotic agents resulted in the closure of many long-term mental hospitals in the UK and USA. These closures released many inmates ‘back into the community’ with varying degrees of success. One review of the UK experience concluded that “Community care was consistently associated with greater patient satisfaction and quality of life across specialties. It was not a cheaper alternative to hospital care” Citation[92]. Conversely, the view that comprehensive community services are necessarily more expensive may not be true either: “Community-based models of care are not inherently more costly than institutions, once account is taken of individuals’ needs and the quality of care. New community-based care arrangements could be more expensive than long-stay hospital care but may still be seen as more cost effective because, when properly set up and managed, they deliver better outcomes” Citation[93].

This discussion reiterates the need for robust and contemporary information on the use, cost, outcome and impact of community HIV prevention and therapeutic services. Community-based organizations need to routinely record who uses their services, estimate the cost of the service, identify outcomes and assess its population-based impact. Such individual-level information has two primary functions: first, to ensure that all information relevant to the services provided are collected for each individual using those services so that longitudinal personal health information can be available over time as part of developing a longitudinal health record for that individual; second, individual-level health information is increasingly being used to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness, efficiency, equity and acceptability of service provision at facility, regional or national levels Citation[13]. Such data need to be collected and used while protecting the confidentiality and security of HIV and other personal identifiable health information Citation[107].

For this to be meaningful, both outcome measures and costing methods need to be standardized within and across countries. Standardizing costing methods both in terms of estimating relevant unit costs and estimating cost per outcome achieved or service provided per unit time can be achieved by the use of standardized tools; a manual and a workbook for costing HIV facilities and services were recently produced by UNAIDS to improve standardization for estimating unit costs in health facilities Citation[108,109] and some community-based organizations have started to adapt these for costing community services Citation[94]. In addition to standardizing costing methods, outcomes of community services should also be standardized, but this may be more difficult to achieve. Reaching agreement on standardizing costing methods and outcome measures will involve close collaboration between national and international professionals, professional bodies, policy–makers and other relevant stakeholders.

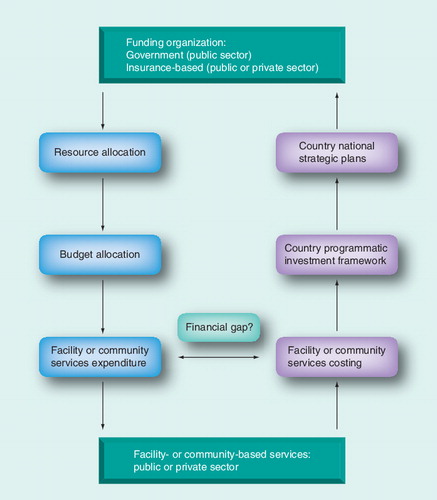

Once standardized data have been collected on the use of services, their unit costs and outcomes, these data can be used to produce robust and contemporary strategic information. Cost estimates of facility and community services need to be compared with expenditures to evaluate the existence of any financial gap between the actual cost of a service and the financial resources spent on providing that service. Estimating recurrent need of resources to provide services ought not to be solely based on expenditure-based assessments because expenditures may not necessarily equate with the actual cost of the service. The focus of many organizations is currently on tracking expenditures as the sole source for determining resource needs. Apart from potential financial gaps, such estimates are often performed on an episodic basis and if not done annually expenditures may underestimate the actual cost of providing services, especially if services are rapidly scaling up or changing.

Cost information assists country policy-makers to develop their investment framework Citation[95], which in turn will enable the production and implementation of more robust national strategic plans Citation[110]. These in turn should inform resource and budget allocations, resulting in expenditures in line with the cost of service provision.

The development of integrated strategic information systems based on individual-level information that monitor and evaluate the use cost, outcome and impact of services provided is one attempt to deal with these issues and collect robust and contemporary strategic information. Costing services need to be performed and interpreted in parallel with tracking resources, budgets and expenditures at the various levels of the healthcare system Citation[12] as they comprise part of the health sector’s ‘resource cycle’ .

Conclusion

As we move from an emergency to a sustained HIV response, organizations involved with providing community services will increasingly have to collect standardized information on the use, cost and outcome of the services in order to satisfy donor organizations, as many donors are increasingly focused on effective and efficient service provision. Given the need to link and integrate HIV and non-HIV services across all age groups, together with the increased global focus on developing NCD services Citation[111] and establishing universal health coverage in these countries Citation[96], many resource-limited countries need to scale up services and strengthen their healthcare system. For this to be sustainable in the long run, countries will need to draw up realistic and costed national strategic plans, track how resources are used, how expenditure compares with the actual cost of providing services and outcome(s) achieved, and adjust spending needs in light of this information Citation[12,13].

Recently, members of the World Bank reviewed the HIV response in a South American country and concluded that “The available data suggests that the HIV/AIDS response is succeeding in keeping the prevalence low and the epidemic concentrated” however, “The complexity of the system and the lack of budgetary and expenditure information have impeded the evaluation of the budgetary efficiency of the HIV/AIDS response” Citation[97]. For countries to move successfully from an emergency HIV response to a sustained response, good financial and economic information is essential strategic information Citation[12,13].

Expert commentary

As funding for HIV services continues to get tighter, partly related to the global economic downturn and other competing health priorities, policy-makers and other stakeholders need to know how effective their HIV programs and services are, their costs and efficiencies, who is using the services and the acceptability to both users and providers of the programs or services. Apart from estimating the cost of providing services, costing exercises also enable policy-makers and other stakeholders to ascertain the existence of ‘funding gaps’ when expenditures can be compared with the actual cost of services provision. Cost and expenditure information need to be used by policy-makers and other stakeholders in conjunction with each other in order to be able to prioritize and invest in specific programs or services. Decisions on where to invest need to be based on the investment framework relevant to that country. The country’s investment framework should then feed into the development of costed national strategic plans for the country, implementation of which should direct resource allocation, budget allocation and actual expenditure. In order to be able to know your epidemic and know your response, robust and contemporary information is required on the use, cost, outcome and impact of programs or services complemented by accurate expenditure data. Standardized resource tracking mechanisms – national health accounts in conjunction with national AIDS spending assessments – will need to be used in conjunction with standardized outcomes and costing methods to monitor and evaluate facility- and community-based HIV programs or services in order for countries to successfully move from an emergency to a sustained HIV response.

Five-year view

Many MICs and LICs need to deal with other health problems in addition to their HIV epidemic, including the increasing burden of people living with noncommunicable diseases. In order to effectively deal with existing and emerging health problems many MICs and LICs will need to develop, expand and integrate their health sector. For many of these countries, a sustainable country response will also need to include developments in other relevant country institutions, including educational, labor and employment sectors, as well as effective governance structures, all of which have economic implications. Sustainable long-term resources will be required to maintain current programs and continue to scale-up services and these should come from national and international sources. International sources should at the very least continue to maintain current levels of funding while national governments also need to raise additional funds from domestic sources to ensure that the implementation of these development programs are as effective and efficient as possible.

Table 1. Community services scoring sheet.

Table 2. Type of community services identified and reviewed.

Table 3. Number of community services studies performed by continent and by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification, mean raw score across studies, range and percentage of maximum score.

Table 4. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of voluntary testing and counseling services by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Table 5. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of outreach and community mobilization services by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Table 6. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of community-based provision of antiretroviral therapy services by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Table 7. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of home-based services by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Table 8. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of provision of condoms by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Table 9. Unit costs and cost–effectiveness of community services for men who have sex with men, female sex workers, injecting drug users and transgender people by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development country classification (2010 purchasing power parity in US$).

Key issues

• Community services play an important role in the HIV response of many countries, involving statutory and informal community-based services, including outreach, community mobilization and community-based treatment and care services. Involving communities directly with healthcare and other social and economic issues is an important aspect of improving conditions in these communities.

• Antiretroviral therapy has increased the number and life expectancy of people living with HIV including older people living with HIV, resulting in an increased need for therapeutic and prevention services that will need linking and integrating with HIV services with other specialist and geriatric services.

• Between 1986 and 2011, only 74 English language studies were published on the cost or cost–effectiveness of community studies from 23 countries, of which 46 (66%) were performed in five countries. Published costing studies enable methods and results to be reviewed by stakeholders within a country or region, allows their robustness to be scrutinized and can facilitate the implementation of standardized costing methods in countries.

• Given that many of these countries need to scale up prevention and therapeutic services, very few countries seem to conduct such studies compared with the need that country policy-makers and other stakeholders have for this type of information.

• Based on the scoring framework devised for community services, mean study scores by continent varied from 42 to 69% of the maximum score of 85, indicating that the quality of studies reviewed varied considerably and many studies were not of a high standard.

• Many of the unit costs presented were estimated based on different costing methods, while great variation was also noted in the outcomes assessed. In order for countries to be able to move from an emergency to a sustained HIV response, those who provide community services will need to routinely collect robust and contemporary information on the use, cost, outcome and impact of their service using standardized outcomes and costing methods.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the comments and suggestions from a variety of colleagues on this paper, in particular Claudia Maier and Marjorie Opuni.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J et al. Life expectancy of persons receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a cohort analysis from Uganda. Ann. Intern. Med. 155(4), 209–216 (2011).

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life-expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 372, 293–299 (2008).

- Beck EJ, Harling G, Gerbase S, DeLay P. The cost of treatment and care for people living with HIV infection: implications of published studies, 1999–2008. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 5(3), 215–224 (2010).

- Mandalia S, Mandalia R, Lo G et al.; NPMS-HHC Steering Group. Rising population cost for treating people living with HIV in the UK, 1997–2013. PLoS ONE 5(12), e15677 (2010).

- Hankins CA, Dybul MR. The promise of pre-exposure prophylaxis with antiretroviral drugs to prevent HIV transmission: a review. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 8(1), 50–58 (2013).

- Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W et al.; INSIGHT SMART Study Group. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 5(10), e203 (2008).

- Tien PC, Choi AI, Zolopa AR et al. Inflammation and mortality in HIV-infected adults: analysis of the FRAM study cohort. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 55(3), 316–322 (2010).

- Eastburn A, Scherzer R, Zolopa AR et al. Association of low level viremia with inflammation and mortality in HIV-infected adults. PLoS ONE 6(11), e26320 (2011).

- Desai S, Landay A. Early immune senescence in HIV disease. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 7(1), 4–10 (2010).

- Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 141–155 (2011).

- Justice AC. HIV and aging: time for a new paradigm. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 7(2), 69–76 (2010).

- Beck EJ, Avila C, Gerbase S, Harling G, De Lay P. Counting the cost of not costing HIV health facilities accurately: pay now, or pay more later. Pharmacoeconomics 30(10), 887–902 (2012).

- Beck EJ, Santas XM, Delay PR. Why and how to monitor the cost and evaluate the cost–effectiveness of HIV services in countries. AIDS 22(Suppl. 1), S75–S85 (2008).

- Beck EJ, Miners AH, Tolley K. The cost of HIV treatment and care. A global review. Pharmacoeconomics 19(1), 13–39 (2001).

- Harling G, Wood R, Beck EJ. Efficiency of Intervention in HIV Infection, 1994–2004. Dis. Manage. Health Outcomes 13, 371–394 (2005).

- Rodriguez-García R, Bonnell R, Wilson D, Njie ND. Investing in Communities Achieves Results: Findings From an Evaluation of Community Responses to HIV and AIDS. Human Development Network, The World Bank, DC, USA (2012).

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum, NY, USA (2007).

- Aldridge RW, Iglesias D, Cáceres CF, Miranda JJ. Determining a cost effective intervention response to HIV/AIDS in Peru. BMC Public Health 9, 352 (2009).

- Ama NO and Seloilwe ES. Estimating the cost of care giving on caregivers for people living with HIV and AIDS in Botswana: a cross-sectional study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 13, 13 (2010).

- Anderson KH, Mitchell JM. Expenditures on services for persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome under a Medicaid home and community-based waiver program. Are selection effects important? Med. Care 35(5), 425–439 (1997).

- Arno PS. The nonprofit sector’s response to the AIDS epidemic: community-based services in San Francisco. Am. J. Public Health 76(11), 1325–1330 (1986).

- Babigumira JB, Sethi AK, Smyth KA, Singer ME. Cost–effectiveness of facility-based care, home-based care and mobile clinics for provision of antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Pharmacoeconomics 27(11), 963–973 (2009).

- Baigis J, Francis ME, Hoffman M. Cost–effectiveness analysis of recruitment strategies in a community-based intervention study of HIV-infected persons. AIDS Care 15(5), 717–728 (2003).

- Beck EJ, Mandalia S, Griffith R et al. Use and cost of hospital and community service provision for children with HIV infection at an English HIV referral centre. Pharmacoeconomics 17(1), 53–69 (2000).

- Bedimo AL, Pinkerton SD, Cohen DA, Gray B, Farley TA. Condom distribution: a cost–utility analysis. Int. J. STD AIDS 13(6), 384–392 (2002).

- Bekker LG, Orrell C, Reader L et al. Antiretroviral therapy in a community clinic – early lessons from a pilot project. S Afr. Med. J. 93(6), 458–462 (2003).

- Bemelmans M, van den Akker T, Ford N et al. Providing universal access to antiretroviral therapy in Thyolo, Malawi through task shifting and decentralization of HIV/AIDS care. Trop. Med. Int. Health 15(12), 1413–1420 (2010).

- Bertrand JT, Njeuhmeli E, Forsythe S, Mattison SK, Mahler H, Hankins CA. Voluntary medical male circumcision: a qualitative study exploring the challenges of costing demand creation in eastern and southern Africa. PLoS ONE 6(11), e27562 (2011).

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL et al. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 113(Suppl. 1), 42–57 (1998).

- Burke HM, Pedersen KF, Williamson NE. An assessment of cost, quality and outcomes for five HIV prevention youth peer education programs in Zambia. Health Educ. Res. 27(2), 359–369 (2012).

- Cerda R, Muñoz M, Zeladita J et al. Health care utilization and costs of a support program for patients living with the human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis in Peru. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 15(3), 363–368 (2011).

- Chandrashekar S, Guinness L, Kumaranayake L et al. The effects of scale on the costs of targeted HIV prevention interventions among female and male sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgenders in India. Sex. Transm. Infect. 86(Suppl. 1), i89–i94 (2010).

- Chandrashekar S, Vassall A, Reddy B, Shetty G, Vickerman P, Alary M. The costs of HIV prevention for different target populations in Mumbai, Thane and Bangalore. BMC Public Health 11(Suppl. 6), S7 (2011).

- Chela CM, Campbell ID, Siankanga Z. Clinical care as part of integrated AIDS management in a Zambian rural community. AIDS Care 1(3), 319–325 (1989).

- Cherin DA, Huba GJ, Brief DE, Melchior LA. Evaluation of the transprofessional model of home health care for HIV/AIDS. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 17(1), 55–72 (1998).

- Cohen DA, Wu SY, Farley TA. Comparing the cost–effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 37(3), 1404–1414 (2004).

- Dandona L, Kumar SP, Ramesh Y et al. Changing cost of HIV interventions in the context of scaling-up in India. AIDS 22(Suppl. 1), S43–S49 (2008).

- Dandona L, Sisodia P, Kumar SG et al. HIV prevention programmes for female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: outputs, cost and efficiency. BMC Public Health 5, 98 (2005).

- Denison JA, Tsui S, Bratt J, Torpey K, Weaver MA, Kabaso M. Do peer educators make a difference? An evaluation of a youth-led HIV prevention model in Zambian Schools. Health Educ. Res. 27(2), 237–247 (2012).

- Fung IC, Guinness L, Vickerman P et al. Modelling the impact and cost–effectiveness of the HIV intervention programme amongst commercial sex workers in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. BMC Public Health 7, 195 (2007).

- Gilson L, Mkanje R, Grosskurth H et al. Cost–effectiveness of improved treatment services for sexually transmitted diseases in preventing HIV-1 infection in Mwanza region, Tanzania. Lancet 350(9094), 1805–1809 (1997).

- Golden MR, Gift TL, Brewer DD et al. Peer referral for HIV case-finding among men who have sex with men. AIDS 20(15), 1961–1968 (2006).

- Gorsky RD, MacGowan RJ, Swanson NM, DelGado BP. Prevention of HIV infection in drug abusers: a cost analysis. Prev. Med. 24(1), 3–8 (1995).

- Grabbe KL, Menzies N, Taegtmeyer M et al. Increasing access to HIV counseling and testing through mobile services in Kenya: strategies, utilization, and cost–effectiveness. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 54(3), 317–323 (2010).

- Haile B. Affordability of home-based care for HIV/AIDS. S. Afr. Med. J. 90(7), 690–691 (2000).

- Hansen K, Woelk G, Jackson H et al. The cost of home-based care for HIV/AIDS patients in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 10(6), 751–759 (1998).

- Harling G, Bekker LG, Wood R. Cost of a dedicated ART clinic. S. Afr. Med. J. 97(8), 593–596 (2007).

- Hausler HP, Sinanovic E, Kumaranayake L et al. Costs of measures to control tuberculosis/HIV in public primary care facilities in Cape Town, South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 84(7), 528–536 (2006).

- Hurley SF, Kaldor JM, Carlin JB et al. The usage and costs of health services for HIV infection in Australia. AIDS 9(7), 777–785 (1995).

- Hutchinson AB, Patel P, Sansom SL et al. Cost–effectiveness of pooled nucleic acid amplification testing for acute HIV infection after third-generation HIV antibody screening and rapid testing in the United States: a comparison of three public health settings. PLoS Med. 7(9), e1000342 (2010).

- Hutton G, Wyss K, N’Diékhor Y. Prioritization of prevention activities to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS in resource constrained settings: a cost–effectiveness analysis from Chad, Central Africa. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 18(2), 117–136 (2003).

- Kahn JG, Marseille E, Moore D et al. CD4 cell count and viral load monitoring in patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: cost–effectiveness study. BMJ 343, d68884 (2011).

- Kahn JG, Harris B, Mermin JH et al. Cost of community integrated prevention campaign for malaria, HIV, and diarrhea in rural Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 346 (2011).

- Kahn JG, Kegeles SM, Hays R, Beltzer N. Cost–effectiveness of the Mpowerment Project, a community-level intervention for young gay men. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 27(5), 482–491 (2001).

- Kasymova N, Johns B, Sharipova B. The costs of a sexually transmitted infection outreach and treatment programme targeting most at risk youth in Tajikistan. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 7, 19 (2009).

- Kipp W, Konde-Lule J, Rubaale T, Okech-Ojony J, Alibhai A, Saunders DL. Comparing antiretroviral treatment outcomes between a prospective community-based and hospital-based cohort of HIV patients in rural Uganda. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 11(Suppl. 2), S12 (2011).

- Kouri YH, Shepard DS, Borras F, Sotomayor J, Gellert GA. Improving the cost–effectiveness of AIDS health care in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Lancet 337(8754), 1397–1399 (1991).

- Kupek E, Dooley M, Whitaker L, Petrou S, Renton A. Demograghic and socio-economic determinants of community and hospital services costs for people with HIV/AIDS in London. Soc. Sci. Med. 48(10), 1433–1440 (1999).

- Marseille EA, Kevany S, Ahmed I et al. Case management to improve adherence for HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia: a micro-costing study. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 9, 18 (2011).

- Marseille E, Kahn JG, Pitter C et al. The cost–effectiveness of home-based provision of antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 7(4), 229–243 (2009).

- Johnson-Masotti AP, Pinkerton SD, Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Wagstaff DA. Cost–effectiveness of a community-level HIV risk reduction intervention for women living in low-income housing developments. J. Prim. Prev. 26(4), 345–362 (2005).

- McCabe CJ, Goldie SJ, Fisman DN. The cost–effectiveness of directly observed highly-active antiretroviral therapy in the third trimester in HIV-infected pregnant women. PLoS ONE 5(4), e10154 (2010).

- McConnel CE, Stanley N, du Plessis JA et al. The cost of a rapid-test VCT clinic in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 95(12), 968–971 (2005).

- Menzies N, Abang B, Wanyenze R et al. The costs and effectiveness of four HIV counseling and testing strategies in Uganda. AIDS 23(3), 395–401 (2009).

- Negin J, Wariero J, Mutuo P, Jan S, Pronyk P. Feasibility, acceptability and cost of home-based HIV testing in rural Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health 14(8), 849–855 (2009).

- Nsutebu EF, Walley JD, Mataka E, Simon CF. Scaling-up HIV/AIDS and TB home-based care: lessons from Zambia. Health Policy Plan. 16(3), 240–247 (2001).

- Petrou S, Dooley M, Whitaker L et al. Cost and utilisation of community services for people with HIV infection in London. Health Trends 27(2), 62–68 (1995).

- Pinkerton SD, Holtgrave DR, DiFranceisco WJ, Stevenson LY, Kelly JA. Cost–effectiveness of a community-level HIV risk reduction intervention. Am. J. Public Health 88(8), 1239–1242 (1998).

- Pinkerton SD, Bogart LM, Howerton D, Snyder S, Becker K, Asch SM. Cost of OraQuick oral fluid rapid HIV testing at 35 community clinics and community-based organizations in the USA. AIDS Care 21(9), 1157–1162 (2009).

- Kumar SG, Dandona R, Schneider JA, Ramesh YK, Dandona L. Outputs and cost of HIV prevention programmes for truck drivers in Andhra Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 9, 82 (2009).

- Renaud A, Basenya O, de Borman N, Greindl I, Meyer-Rath G. The cost–effectiveness of integrated care for people living with HIV including antiretroviral treatment in a primary health care centre in Bujumbura, Burundi. AIDS Care 21(11), 1388–1394 (2009).

- Richter A, Loomis B. Health and economic impacts of an HIV intervention in out of treatment substance abusers: evidence from a dynamic model. Health Care Manag. Sci. 8(1), 67–79 (2005).

- Rosen S, Ketlhapile M. Cost of using a patient tracer to reduce loss to follow-up and ascertain patient status in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 15(Suppl. 1), 98–104 (2010).

- Rosen S, Long L, Sanne I. The outcomes and outpatient costs of different models of antiretroviral treatment delivery in South Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 13(8), 1005–1015 (2008).

- Sansom SL, Anthony MN, Garland WH et al. The costs of HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence programs and impact on health care utilization. AIDS Patient Care STDS 22(2), 131–138 (2008).

- Shrestha RK, Sansom SL, Kimbrough L et al. Cost–effectiveness of using social networks to identify undiagnosed HIV infection among minority populations. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 16(5), 457–464 (2010).

- Shrestha RK, Clark HA, Sansom SL et al. Cost–effectiveness of finding new HIV diagnoses using rapid HIV testing in community-based organizations. Public Health Rep. 123(Suppl. 3), 94–100 (2008).

- Shrestha RK, Sansom SL, Schulden JD et al. Costs and effectiveness of finding new HIV diagnoses by using rapid testing in transgender communities. AIDS Educ. Prev. 23(3 Suppl), 49–57 (2011).

- Siregar AY, Komarudin D, Wisaksana R, van Crevel R, Baltussen R. Costs and outcomes of VCT delivery models in the context of scaling up services in Indonesia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 16(2), 193–199 (2011).

- Stevinson K, Martin EG, Marcella S, Paul SM. Cost–effectiveness analysis of the New Jersey rapid testing algorithm for HIV testing in publicly funded testing sites. J. Clin. Virol. 52(Suppl. 1), S29–S33 (2011).

- Sweat M, Kerrigan D, Moreno L et al. Cost–effectiveness of environmental-structural communication interventions for HIV prevention in the female sex industry in the Dominican Republic. J. Health Commun. 11(Suppl. 2), 123–142 (2006).

- Terris-Prestholt F, Kumaranayake L, Foster S et al. The role of community acceptance over time for costs of HIV and STI prevention interventions: analysis of the Masaka Intervention Trial, Uganda, 1996–1999. Sex Transm. Dis. 33(10 Suppl), S111–S116 (2006).

- Terris-Prestholt F, Kumaranayake L, Ginwalla R et al. Integrating tuberculosis and HIV services for people living with HIV: costs of the Zambian ProTEST initiative. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 6, 2 (2008).

- Thielman NM, Chu HY, Ostermann J et al. Cost–effectiveness of free HIV voluntary counseling and testing through a community-based AIDS service organization in northern Tanzania. Am. J. Public Health 96(1), 114–119 (2006).

- Tramarin A, Milocchi F, Tolley K et al. An economic evaluation of home-care assistance for AIDS patients: a pilot study in a town in northern Italy. AIDS 6(11), 1377–1383 (1992).

- Uys L, Hensher M. The cost of home-based terminal care for people with AIDS in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 92(8), 624–628 (2002).

- Vickerman P, Terris-Prestholt F, Delany S, Kumaranayake L, Rees H, Watts C. Are targeted HIV prevention activities cost-effective in high prevalence settings? Results from a sexually transmitted infection treatment project for sex workers in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sex. Transm. Dis. 33(10 Suppl), S122–S132 (2006).

- Wilson AR, Kahn JG. Preventing HIV in injection drug users: choosing the best mix of interventions for the population. J. Urban Health 80(3), 465–481 (2003).

- Wilson LS, Moskowitz JT, Acree M et al. The economic burden of home care for children with HIV and other chronic illnesses. Am. J. Public Health 95(8), 1445–1452 (2005).

- Meng X, Anderson AF, Hou X et al. A pilot project for the effective delivery of HAART in rural China. AIDS Patient Care STDS 20(3), 213–219 (2006).

- Zergaw A, Damen HM, Ahmed A. Cost–effectiveness analysis of health care intervention in Meskanena Mareko Wereda, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 16(3), 267–276 (2002).

- Killaspy H. From the asylum to community care: learning from experience. Br. Med. Bull. 79–80, 245–258 (2006).

- Knapp M, Beecham J, McDaid D, Matosevic T, Smith M. The economic consequences of deinstitutionalisation of mental health services: lessons from a systematic review of European experience. Health Soc. Care Community 19(2), 113–125 (2011).

- International Alliance HIV/AIDS. Costing Community Mobilisation Within the HIV and AIDS Response: Piloting a Method to Understand the Costs of Community Mobilization Within the Proposed UNAIDS Investment Framework. International Alliance HIV/AIDS, Brighton, UK (2012).

- Schwartländer B, Stover J, Hallett T et al.; Investment Framework Study Group. Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet 377(9782), 2031–2041 (2011).

- Rodin J, de Ferranti D. Universal health coverage: the third global health transition? Lancet 380(9845), 861–862 (2012).

- Antonio Moreno A, Álvarez-Rosete A, Nuñez RL et al. Evidence-Based Implementation Efficiency Analysis of the HIV/AIDS National Response in Colombia. Policy Research Working Paper 6182. Human Development Network, Health, Nutrition and Population Unit, The World Bank, DC, USA (2012).

Websites

- UNAIDS. Global Report, UNAIDS report on the global epidemic (2012). www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_with_annexes_en.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- WHO. The strategic use of antiretrovirals to help end the HIV epidemic (2012). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75184/1/9789241503921_eng.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- African Union. Roadmap on shared responsibility and global solidarity for AIDS, TB and malaria response in Africa. www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/Shared_Res_Roadmap_Rev_F%5b1%5d.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- World Bank. World development indicators and global development finance. http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=12&id=4&CNO=2 (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database. www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/01/weodata/weoselser.aspx?c=614%2c666%2c638%2c668%2c616%2c674%2c748%2c676%2c618%2c678%2c622%2c684%2c624%2c688%2c626%2c728%2c628%2c692%2c632%2c694%2c636%2c714%2c634%2c716%2c662%2c722%2c718%2c724%2c199%2c734%2c738%2c742%2c746%2c754%2c698&t=35 (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- Rosenberg M. The number of countries in the world, About.com geography. http://geography.about.com/cs/countries/a/numbercountries.htm (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- UNAIDS/PEPFAR. Interim guidelines on protecting the confidentiality and security of HIV information: proceedings from a workshop, 15–17 May 2006, Geneva, Switzerland. http://data.unaids.org/pub/manual/2007/confidentiality_security_interim_guidelines_15may2007_en.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- UNAIDS. Manual for costing HIV facilities and services. www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/20110523_manual_costing_HIV_facilities_en.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- UNAIDS. Workbook for the collection of cost information on HIV facilities and services. www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2011/20110523_workbook_cost_info_en.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- UNAIDS and ADB. Costing guidelines for HIV/AIDS intervention strategies, ADB – UNAIDS study series: tool I, Geneva, February 2004. http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc997-costing-guidelines_en.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)

- United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. http://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/UN%20Political%20Declaration%20on%20NCDs.pdf (Accessed 27 January 2013)