Pollen counts courtesy of the National Pollen and Aerobiology Research Unit.

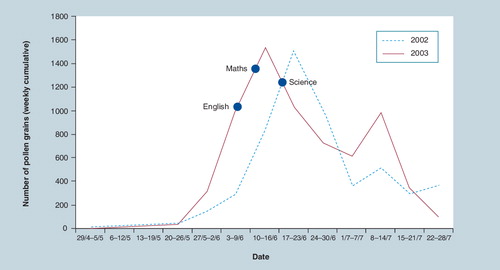

Crucial examinations take place during adolescence in most societies, which can have a major impact on an individual’s career trajectory. Examination boards have recognized that some health problems can impact on a student’s ability to perform in examinations and in response have introduced measures to take account of this – for example, offering extra examination time for students with dyslexia. However, this is not yet generally the case in relation to students with hayfever (also known as seasonal or intermittent allergic rhinitis). This is concerning since, in the UK, critical examinations for children 15–18 years of age take place over a 6-week period during May and June when grass pollen counts are typically at their highest (see ) Citation[1]. Also of relevance is that tree pollens tend to peak from late February to the middle of May when students are likely to be revising for their examinations. Hayfever thus has the potential to disrupt students both when revising for and sitting examinations, which has led some quarters to call for the timing of examinations to be changed. In this article, we review the evidence of the disease burden associated with hayfever and summarize recent evidence that suggests that poorly controlled hayfever can adversely impact on examination performance, drawing on these data to reflect on the question of whether students with hayfever are indeed unfairly disadvantaged by being forced to prepare for and sit examinations during the peak of the pollen season.

Defining & categorizing allergic rhinitis

Rhinitis refers to inflammation of the nasal lining and tends to manifest with symptoms of sneezing, rhinorrhoea, nasal itch and nasal blockage/congestion; conjunctival symptoms are often present, particularly if the underlying etiology is allergic in origin Citation[2]. Allergic rhinitis refers to IgE-mediated disease in which exposure to aeroallergens in previously sensitized people results in mast cell degranulation and the release of inflammatory mediators. These allergic triggers can be seasonal, including tree, grass and weed pollens and mold spores, or perennial, this latter category including house dust mite and animal dander. The seasonal variety is more commonly known as hayfever.

The Allergic Rhinitis in Asthma classification scheme, which is based on a combination of the frequency and severity of symptoms, was introduced in 2001 and reinforced in 2008; this subdivides allergic rhinitis into intermittent or persistent disease forms Citation[3,4]. In the UK, intermittent rhinitis is virtually synonymous with the seasonal category or hayfever, although this overlap is far less clear in equatorial regions Citation[5].

High prevalence & disease burden of allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis is a global health problem affecting males and females of all ages from all ethnic groups and socioeconomic backgrounds. In the UK, allergic diseases currently have a lifetime prevalence of approximately 30% in the general population Citation[6,7], although this proportion is projected to increase. Rhinitis is one of the most common allergic problems in young people Citation[8], affecting 40% of 13–14-year olds Citation[9]; it is closely followed by asthma, which affects approximately 30% of young people Citation[9].

There are many national and international studies describing the prevalence of allergic rhinitis and its risk factors Citation[3], many of these based on the International Study on Asthma and Allergy in Childhood Citation[9], which aimed to describe the prevalence and severity of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in children examined at different centers and to make comparisons within and between countries over time. Phase III of the study was planned to assess time trends over a period of at least 5 years in the prevalence of symptoms by repeating the initial Phase I cross-sectional survey. Most centers showed a change in the prevalence of symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis for the age groups 6–7 and 13–14 years of age (80 and 70%, respectively). In both age groups the prevalence was found to have increased more often than it decreased Citation[10]. Combined data from all centers showed that the proportion of children with symptoms of more than one of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema rose slightly from Phase I to Phase III.

Rhinitis and asthma frequently coexist, with population surveys estimating that up to 40% of all allergic rhinitis patients have asthma and that up to 80% of people with asthma have rhinitis Citation[11–13]. Other common comorbidities include allergic conjunctivitis, allergic sinusitis and eczema.

Allergic rhinitis causes a significant health burden to the individual, and the impairment of quality of life experienced by patients with rhinitis is at least as severe as that of patients with asthma Citation[4]. It is known to reduce quality of life, can impair sleep and leisure activities and can reduce academic performance Citation[14]. It can also cause bronchial hyperreactivity.

Most of the economic analyses performed to date are based on US data; in 2003, the estimated annual costs of allergic rhinitis ranged from US$2 to $5 billion Citation[15]. These estimates include indirect costs such as reduction in productivity, which are difficult to accurately estimate. In the UK, direct National Health Service costs for managing allergic problems were estimated at over £1 billion per annum Citation[7]. The costs to society resulting from allergic rhinitis are believed to be increasing Citation[16].

Evidence of a detrimental impact on education performance

Studies have shown that adults with allergic rhinitis experience a reduction in cognitive function and psychological wellbeing Citation[17], and that children with symptomatic allergic rhinitis had significant learning impairment (in a simulated educational setting) compared with asymptomatic controls Citation[18]. This detrimental impact has been shown to be compounded by the use of sedating antihistamines Citation[19]. A more recent study has shown that when compared with healthy controls, allergic rhinitis sufferers experience increased difficulty with tasks requiring sustained attention Citation[20].

A study carried out in 2007 attracted much media attention, resulting in headlines such as: “Hayfever drugs cost students an exam grade” Citation[21]. This large case–control study involving 1834 students investigated whether hayfever adversely impacts examination performance in UK teenagers. Walker et al. looked at the association between current symptomatic hayfever and rhinitis medication and the risk of unexpectedly dropping a grade in summer examinations when compared with the mock examinations Citation[21]. For clarity, the normal expectation is that most students will achieve at least the same grade as achieved in their mock examinations – which mainly take place in the winter months – and so a drop in grade would thus be unexpected. The study showed that those who had hayfever symptoms on any examination day were more likely to drop a grade between their mock and final examination for maths, english and science (odds ratio [OR]: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.13–1.81; p = 0.002). This risk increased if students were taking a sedative antihistamine at the time of their examinations (OR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.06–2.75; p = 0.03). Students with more severe hayfever, as measured by symptom scores on the day of the examination and a previous history of summer hayfever symptoms, were at an even greater risk of dropping a grade.

Although this case–control study in naturally occurring populations adds important evidence of the potential bias against students with hayfever, more studies are needed to confirm this finding. This is because case–control studies are a relatively weak design for establishing the causality of the relationships. Importantly, there is currently no evidence of reversibility, which is one of the criteria used to infer a causal relationship between hayfever and a detrimental impact on examination performance Citation[21].

Treatment options & service provision

Many allergic rhinitis sufferers have persistent symptoms that require pharmacotherapy. A recent systematic review of the randomized controlled trial literature of the effectiveness of commonly used pharmacological treatments in the management of people with hayfever recommended that nonsedating antihistamines and nasal corticosteroids should be first-line treatment options in those with mild-to-moderate disease Citation[22]. Many studies have examined the sedative properties of antihistamines Citation[23,24] and have shown significant sedative effects of first-generation antihistamines, but limited sedative effects of second-generation antihistamines. Despite current guidelines Citation[3], many children in the case–control study referred to previously were taking sedating antihistamines at the time of their examinations. Adherence issues are important as most treatments are given over long time periods and a failure to take treatments regularly may be central to why treatments often ‘fail’. Allergen immunotherapy is an effective treatment option in those with more severe disease Citation[25].

Treatments for hayfever aim to minimize or eliminate symptoms, optimize quality of life and reduce the risk of developing comorbidities. A report published in 2003, ‘Allergy – the unmet need’, commissioned by the Royal College of Physicians, clearly demonstrated current deficiencies in National Health Service allergy services in the UK in both primary and secondary care Citation[26,27]. More recently, considerable variation in the awareness and management of allergic rhinitis was revealed in a survey of general practitioners, despite the fact that their practices had a self-declared interest in the management of allergic and respiratory disorders Citation[28]. Under-diagnosis of allergic rhinitis remains a problem and the proportion of undiagnosed patients is as high as 60% Citation[29]. Part of the problem appears to lie in the fact that many patients do not consult their general practitioner about their allergic rhinitis symptoms, and seek over-the-counter pharmacotherapy, while many may not recognize their symptoms as allergic rhinitis at all.

The House of Lords Science and Technology Committee report on Allergy (2006–2007) recommended that the Department for Children, Families and Schools should review the clinical care that children receive at school, and should reassess the way they are supported through the examination season Citation[30]. However, it is important that primary healthcare professionals also have the necessary knowledge and skills to be able to manage patients with allergy symptoms effectively; there are now a number of pharmacological and educational interventions that have been shown to improve quality of life in allergic patients Citation[31,32], and further work on educational interventions in teenagers is underway Citation[33].

Should examination timetables be changed?

The current secondary school examination timetable combined with the application process for higher education is well established in the UK. Moving the examinations to the winter months may offset any potential disadvantage faced by adolescent hayfever sufferers, although this would have major knock-on implications for entry into higher education, which currently takes place after the summer break. There has been some discussion of post-qualification application to university Citation[34], where students would sit their advanced (‘A’) levels/higher grades and obtain their results prior to an application for higher education, which may add more weight to the argument for earlier examination timings. The degree of cooperation between the education establishments required to coordinate such a radical change may well be prohibitive and, given that safe, effective and inexpensive treatments are available, could be considered unnecessary. However, consideration of the evidence of the number of people affected by allergic rhinitis and its impact on their future should certainly be made in any future Department for Education and Skills curriculum reviews.

Conclusion

10 years ago, an editorial in Paediatric Allergy and Immunology posed the question of whether there was a case for unfair discrimination against hayfever sufferers sitting examinations in the summer Citation[35]. This question is still relevant as we know that uncontrolled allergic rhinitis can significantly reduce quality of life and interfere with attendance through school absences. There is also a small but consistent body of evidence pointing to the fact that examination preparation and performance may be adversely affected by allergic rhinitis, particularly if patients are taking sedative medications. However, we also now know that it should be possible to achieve good symptom control with relatively simple medication regimens in the vast majority of young people. Delivering optimal care (defined pragmatically as timely and accurate diagnosis of hayfever and related comorbidities, education and empowerment of patients towards effective self-management, and appropriate pharmacotherapy) must then represent the mainstay approach to tackling the disadvantage that many young people with hayfever currently experience. In those with resistant disease, there is also the need to consider hayfever as a mitigating factor, both in relation to examination preparation and when sitting examinations. In the longer term, we believe it would make sense to review the timing of examinations in any future major review of course and examination scheduling with a view to, if possible, moving these to the winter months.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Victoria Hammersley is funded by the Scottish Chief Scientist Office as part of a Research Training Fellowship and is currently undertaking a trial exploring the effect of healthcare professional education on quality of life of adolescents with hayfever. Samantha Walker is Director of Education & Research at an educational charity that focuses on the education of health professionals as a key factor in improving patient health and quality of life. Aziz Sheikh has undertaken advisory work for a range of companies that manufacture diagnostic tests and pharmaceutical treatments for the management of seasonal allergic rhinitis. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Emberlin J, Mullins J, Corden J et al. Regional variations in grass pollen seasons in the UK, long-term trends and forecast models. Clin. Exp. Allergy29(3), 347–356 (1999).

- Scadding GK. Allergic rhinitis in children. Paediatr. Child Health18(7), 323–328 (2008).

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008. Allergy63(Suppl. 86), 8–160 (2008).

- World Health Organization Initiative; Bousquet J, van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev NJ. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.108, S147–S334 (2001).

- Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy38(1), 19–42 (2008).

- Anandan C, Gupta R, Simpson C, Fischbacher C, Sheikh A. Epidemiology and disease burden from allergic disease in Scotland: analyses of national databases. J. R. Soc. Med.102, 431–442 (2009).

- Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Burden of allergic disease in the UK: secondary analyses of national databases. Clin. Exp. Allergy34(4), 520–526 (2004).

- Punekar Y, Sheikh A. Estabishing the incidence and prevalence of clinician-diagnosed allergic conditions in children and adolescents using routinely collected data from general practices. Clin. Exp. Allergy39, 1209–1216 (2009).

- International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet351, 1225–1232 (1998).

- Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet368(9537), 733–743 (2006).

- Casale TB, Dykewicz MS. Clinical implications of the allergic rhinitis–asthma link. Am. J. Med. Sci.327(3), 127–138 (2004).

- Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Liard R, Bousquet J, Neukirch F. Quality of life in allergic rhinitis and asthma. A population-based study of young adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.162(4), 1391–1396 (2000).

- Walker S, Sheikh A. Self reported rhinitis is a significant problem for patients with asthma. Primary Care Resp. J.14(2), 83–87 (2005).

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Dolovich J. Assessment of quality of life in adolescents with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Development and testing of a questionnaire for clinical trials. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.93, 413–423 (1994).

- Blaiss M. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: burden of disease. Allergy Asthma Proc.28, 393–397 (2007).

- Lancet T. Allergic rhinitis: common, costly, and neglected. Lancet371(9630), 2057–2057 (2008).

- Kremer B, den Hartog H, Jolles J. Relationship between allergic rhinitis, disturbed cognitive functions and psychological well-being. Clin. Exp. Allergy32, 1310–1315 (2002).

- Vuurman EF, van Veggel LM, Uiterwijk MM, Leutner D, O’Hanlon JF. Seasonal allergic rhinitis and antihistamine effects on children’s learning. Ann. Allergy71(2), 121–126 (1993).

- Vuurman E, van Veggel L, Sanders R, Muntjewerff N, O’Hanlon J. Effect of semprex-D and diphenhydramne on learning in young adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol.76, 247–252 (1996).

- Hartgerink-Lutgens I, Vermeeren A, Vuurman E, Kremer B. Disturbed cognitive functions after nasal provocation in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy39(4), 500–508 (2009).

- Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M, Cullinan P, Harris J, Sheikh A. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: case–control study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.120(2), 381–387 (2007).

- Sheikh A, Singh Panesar S, Dhami S. Seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin. Evid.14, 684–695 (2005).

- Mann R, Pearce G, Dunn N, Shakir S. Sedation with “non-sedating” antihistamines: four prescription-event monitoring studies in general practice. BMJ320, 1184–1186 (2000).

- Ramaekers J, Uiterwijk MM, O’Hanlon JF. Effects of loratadine and cetirizine on actual driving and psychometric test performance, and EEG during driving. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.42, 363–369 (1992).

- Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.1, CD001936 (2007).

- Levy ML, Price D, Zheng X, Simpson C, Hannaford P, Sheikh A. Inadequacies in UK primary care allergy services: national survey of current provisions and perceptions of need. Clin. Exp. Allergy34(4), 518–519 (2004).

- Hazeldine M, Worth A, Levy ML, Sheikh A. Follow-up survey of general practitioners’ perceptions of UK allergy services. Prim. Care Respir. J.19(1), 84–86 (2010).

- Ryan D, Grant-Casey J, Scadding GK, Pereira S, Pinnock H, Sheikh A. Management of allergic rhinitis in UK primary care: baseline audit. Prim. Care Respir. J.14, 204–209 (2005).

- Bauchau V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur. Respir. J.24(5), 758–764 (2004).

- House of Lords Science and Technology Committee: Allergy. Report No.1. 2006–2007. The Stationery Office Limited, London, UK (2007).

- Sheikh A, Panesar S, Salvilla S. Hayfever in adolescents and adults. Clin. Evidence11, 509 (2009).

- Sheikh A, Khan-Wasti S, Price D, Smeeth L, Fletcher M, Walker S. Standardized training for healthcare professionals and its impact on patients with perennial rhinitis: a multi-centre randomized controlled trial. Clin. Exp. Allergy37(1), 90–99 (2007).

- Hammersley V, Elton R, Walker S, Sheikh A. Protocol for the adolescent hayfever trial: cluster randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention for healthcare professionals for the management of school-age children with hayfever. Trials (2010) (In Press).

- Tomlinson M. 14–19 Curriculum and Qualifications Reform. Final Report of the Working Group on 14–19 Reform. Working Group on 14–19 Reform, London, UK (2004).

- Warner JO. Seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis and examinations: is this unfair discrimination? Pediatric Allergy Immunol.11(3), 129–130 (2000).