Abstract

Aim: This study aimed to identify the perspective knowledge, attitudes, and barriers of community pharmacists in promoting breast cancer health. Methods: An internet-based self-administrated questionnaire was distributed using social media groups to the community pharmacists in Jordan. Results: A 76.7% of the pharmacists had insufficient knowledge score of breast cancer and 92.7% had positive attitude. Access to breast cancer educational materials was the major barrier to pharmacists. A significant association was found between pharmacists' knowledge and breast cancer educational materials being given to patients (p < 0.001). Conclusion: Despite the low breast cancer knowledge score and stated barriers that could prevent actualizing community pharmacists' role, they had positive attitude toward educating patients about breast cancer health.

Plain Language Summary

The aim of this study was to evaluate pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, and barriers about breast cancer health promotion among community pharmacists. An internet-based self-administrated questionnaire was distributed using social media groups to the community pharmacists in Jordan. 76.7% of the pharmacists had a poor knowledge score of breast cancer and 92.7% had a positive attitude. The major barrier to pharmacists was access to breast cancer educational materials. A strong association was found between pharmacists' knowledge and breast cancer educational materials being given to patients. Also, community pharmacists had a positive attitude toward educating patients about breast cancer health.

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide with more than 9.6 million deaths and 18.1 million new cases recorded in 2018. These figures are forecast to rise globally in an aging population in the coming two decades [Citation1]. Cancer is a malignant disease which originates from a single cell that undergoes a multistep mechanism called carcinogenesis. This is where a single cell starts to behave abnormally, multiplies uncontrollably and persistently, accumulates changes, forming masses of cancerous cells called tumour, and eventually, invading neighboring tissues [Citation2,Citation3]. Note that breast cancer is the most predominant cancer and the leading cause of death among women in developing countries [Citation4]. It has been estimated that 1 in every 200 women would develop breast cancer under the age of 40 years [Citation5]. In addition, the International Agency for Research on Cancer estimates that there were 19.3 million new cancer cases and 10.0 million cancer deaths in 2020 [Citation6]. In Jordan, the most common malignancy is breast cancer which is the third leading cause of cancer death after lung and colorectal cancers [Citation7,Citation8]. In addition, there is a significant increase in the number of new cases among younger women; who unfortunately present with more advance stage of breast cancer comparing to Western countries [Citation7]. Similarly, many patients turn up to medical centers for the first time having advanced stages of breast cancer, even they received initiatives to screen for breast cancer. Avoidance of breast cancer screening could be due many reasons as lack of awareness of the importance of screening and partly probably, embarrassment of the screening methods [Citation9]. This highlights the importance of increasing awareness of early screening for breast cancer among women and emphasizes on the chances of full recovery of early discovery of breast cancer which might improve survival rate [Citation10–13]. Early detection of breast cancer includes both breast self-examination and clinical breast examination, which was recommended internationally including guidelines of the those by the American Cancer Society [Citation14]. After detection of breast cancer, patients undertake long-term treatment modalities which require appropriate counseling and to adhering strictly to prescribed regimen; otherwise many of these treatment modalities are likely to fail [Citation15].

One of the most accessible and trusted healthcare providers are pharmacists, who provide direct patient care centered on patient needs [Citation16]. Pharmacists are expert in medications; providing patients with proper counseling and education on how to get the best benefit of their treatment modalities [Citation17]. Several researches reported that counseling patients of breast cancer about chemotherapy and its associated side effects reduced side effects and improved the quality of life [Citation18–20]. Moreover, counseling and educating patients of breast cancer about their medications led to decrease anxiety level and enhance the psychological outcomes in those patients in comparison to patients with inadequate counseling and education [Citation21].

Noteworthy, pharmacists should be aware about chemotherapy prescribing errors and its tragic consequences for the oncology patients which lead to treatment failure in cancer patients in different protocols. It was reported in a cross-sectional observational study performed on 500 cancer patients, to identify the incidence of prescribing medication errors (PME) involving chemotherapeutic agents. Findings showed that all the cases contained at least one error and the risk factors predicting the prescribing errors were the protocol type, the tumor type, the toxicity type of the antineoplastic regimen which should be prevented for improvement of treatment plan [Citation22]. In addition, pharmacists play a vital role in decreasing health literacy of community. A study was conducted in an emergency hospital on 1025 and 1024 patients to detect the rate and the severity of medication errors using direct observation before and after the implementation of educational tools. The findings of this study highlight the importance of pharmacist interventions in declining all types of medication errors and in significantly reducing the rate of medication errors in both pre-intervention and post-intervention phase. Noteworthy, clinical pharmacist interventions which improved the knowledge and awareness of nurses about medication errors in an emergency hospital environment were shown to be effective in reduction of the rate and severity of medication administration errors among nurses [Citation23].

Community pharmacies are easily accessible to patients due to their location which is widely distributed within the communities, in addition to the extended working h, and free counseling about medications being dispensed in the pharmacy [Citation24]. Therefore, community pharmacists can play an integral role in increasing the awareness of breast cancer especially in women who visit community pharmacies considerably [Citation25,Citation26]. Pharmacists have considerable knowledge of topics related to breast cancer and presumably can play an important role in supporting breast cancer health promotion among patients [Citation16,Citation27,Citation28]. Notably, many studies have been conducted to assess the pharmacists' understanding about breast cancer health promotion and found a significant gaps in their knowledge [Citation29–31].

A search of the literature revealed one study has been conducted in Jordan to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and barriers of community pharmacists toward breast cancer health promotion since 2015 [Citation32]. Up to my knowledge, no studies have been set out to explore further gaps, improvements, and subtle changes over time of the knowledge, attitudes, and barriers of community pharmacists concerning health promotion of breast cancer in in Jordan especially after COVID-19 pandemic, and their role in promoting the health of patients with breast cancer visiting the pharmacies. In addition, this study aimed at identifying predictors of the knowledge in association with community pharmacists' sociodemographic and practice variables of their knowledge and attitudes toward breast cancer health promotion.

Methods

Design & data collection

To meet the study objectives a cross-sectional design was carried out. Data were collected between the period January–March 2022 using an internet-based self-administrated questionnaire which was created using Google Forms. The participants in our study were recruited through social media platforms. The questionnaire was distributed across several Facebook and WhatsApp groups of pharmacists among different areas in Jordan. These social media groups were created as a tool for general communication within the pharmacist's community. Informed consent was obtained from the participants as a pre-request to proceed in participation.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on 95% confidence level, and 5% confidence interval, and total pharmacists in Jordan is 20,000. The sample size calculation revealed the need for at least 378 pharmacists. However, for the purpose of enhancing the generalizability of the results, a minimum sample of 605 pharmacists was intended.

Study tool

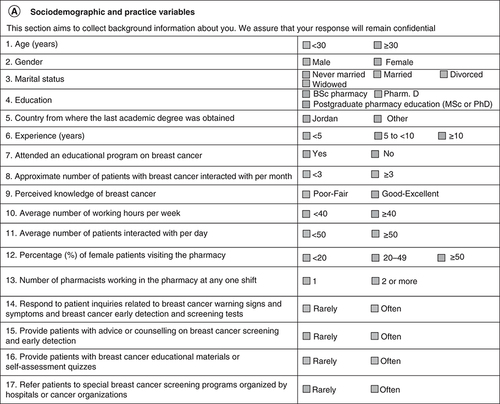

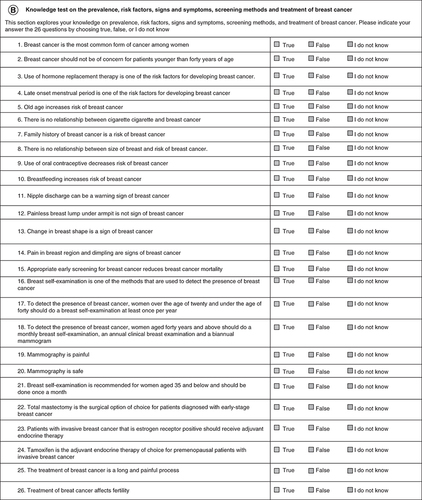

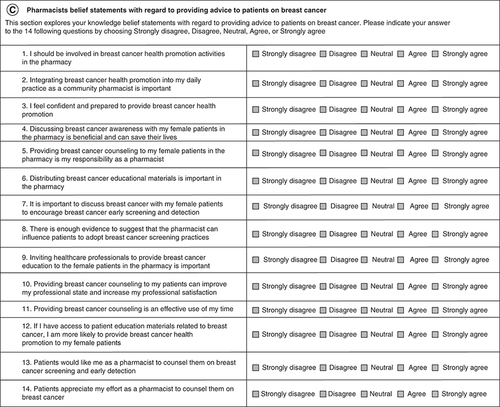

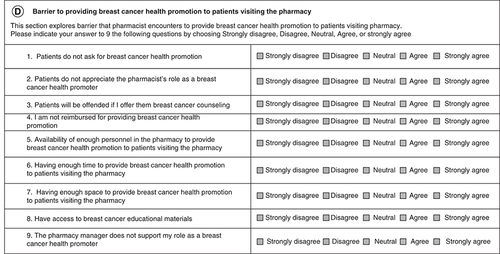

The questionnaire was created especially for the purpose of this study. Most of the questions related to the knowledge, attitudes, and barriers were selected from the literature [Citation32–34]. As was outlined in a previous study published in 2021 [Citation34], the questionnaire was divided in to 4 sections – the first section included the sociodemographic and practice variables of community pharmacists, the second section contained 26 items to test the knowledge of the community pharmacists about breast cancer prevalence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, screening methods, and treatment, the third section used 14 questions to study the attitudes and beliefs of the pharmacists and the final section included 9 questions related to the barriers faced by pharmacists in promoting breast cancer health to patients coming into their pharmacy. The detailed questionnaire can be seen in .

(A) Sociodemographic and practice variables. (B) Knowledge test on the prevalence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, screening methods and treatment of breast cancer. (C) Pharmacists belief statements with regard to providing advice to patients on breast cancer. (D) Barrier to providing breast cancer health promotion to patients visiting the pharmacy.

Face validity & pilot testing

Face validity was revised by a group of experts in the field and was constituted of two oncologists, two community pharmacists, and two clinical pharmacists. A scale of 1–5 (1 indicated not relevant and 5 indicated highly relevant) was used to rate each item in the questionnaire. Items included in the final questionnaire were rated as relevant and highly relevant by the reviewers. Conflicting ratings were resolved by discussion and consensus. To ensure comprehensibility and clarity of the questionnaire, pilot test was performed. 20 community pharmacists were asked to answer the questionnaire, then after a short period (one week), the same pharmacists were answered the questionnaire in a second round. In addition, the stability and reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed in another study [Citation31], where the stability of scores over a short period of time was accepted as Pearson's correlation coefficients: 90%, 95% CI: 0.91–0.99, p-value < 0.001. The questionnaire internally consistent was also accepted, Cronbach's alpha: 83.9%, 95% CI: 81.4–85.9%, p-value < 0.001.

Data analysis & statistical method

Data collected were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25.0 (SPSS). Categorical and ordinal variables were shown as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Univariate statistical analysis was used to determine whether there was an association between the variables, the χ2 test for association was used. Phi (Φ) factor (or Cramer's V coefficient, when having more than two dichotomous variables) was used to evaluate the strength of association of a nominal-by-nominal relationship (and is a measure of effect size), where the value of 1 indicates a complete association, “0” indicating no association, small association 0.1, medium association 0.3 and large association 0.5. Phi (Φ) or Cramer's V coefficient was only illustrated when there is a statistical significance. Multivariable logistic regression (backward stepwise) model was used to eliminate independent predictors with non-statistically significant contributions (i.e., P more than 0.05). For evaluating the quality of the logistic regression results (i.e., model fit), the overall statistical significance tests for models were carried out. The Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients was used to measure how well the final model predicted categories compared with the baseline model and other previous models in the backward stepwise approach (i.e., p for the final model should be < 0.05). To understand how much variation in the dependent variable can be explained by the model; the Nagelkerke R Square (R2) was reported [Citation35,Citation36]. To assess the effectiveness of the predicted classification against the actual classification, percentage accuracy in classification, sensitivity and specificity were calculated and reported. To align with the standard recommendations for logistic model output quality, discriminative ability testing was carried out through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [Citation36,Citation37]. ROC results were used to evaluate the ability of the final models to identify the predicted readmission status compared with the observed actual readmission status. Area Under the Curve (AUC) represents the overall accuracy of logistic prediction models (sensitivity and specificity matrix), in which AUC = 1.00 means 100% accurate [Citation38,Citation39].

Method for scoring

Knowledge

Each question with a correct answer, a 1 point, and a wrong answer -0.5 point. Answer with did not know = 0.0 point. As the present study has 26 questions, the highest possible score = 26 points and the minimum possible score = -13 points. Participants were categorized into binary classification based on their score (<50%, or >50%).

Attitude & barrier

The following points were assigned to answer questions: strongly disagree (-2), disagree (-1), neutral (0), agree (1), strongly agree (2).

Attitude has 14 statements, accordingly, the highest possible score = 28 points, the minimum possible score = -28 points. Based on attitude total points the participants were categorized into negative, neutral and positive attitude groups, with a total point from -28 to -1, zero and from +1 to +28, respectively.

Perceived Barriers were 9 statements accordingly, the highest possible score = 18, the minimum possible score = -18. Based on Barriers total points the participants were categorized into negative, barrier dominant neutral, and not barrier dominant groups, with a total point from -18 to -1, 0, and from +1 to +18, respectively.

Results

Demographic information for the responders

A total of 605 pharmacists successfully participated in the present study (response rate: 90.3%). As expected, females (56.2%) pharmacists were more than males (43.8%). Pharmacists younger than 30 years (54%) were more than those older than 30 (46%). Most responders were having BSc Pharmacy (Almost 69%), almost one-quarter of pharmacists (24%) were PharmDs and less than 10% were postgraduates. Pharmacists with less than 5 years' experience were 42.1%, and those with more than 10 years' experience were 20%. More than half of pharmacists had attended educational programs (Almost 60%), perceived their knowledge about breast cancer as good–excellent (65.1%), worked more than 40 h per week (59.5%), worked in a pharmacy with 2 or more pharmacists (61.3%), answered with the often option for the following statements: response to breast cancer warning signs and symptoms and breast cancer early detection and screening tests (64.1%), provide patients with breast cancer educational materials or self-assessment quizzes (55%) and refer patients to special breast cancer screening programs organized by hospitals or cancer organizations (54.2%). All demographic variables are listed in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic and practice variables of the pharmacists who took part in the study (n = 605).

Scores & categories for knowledge, attitude & barrier

illustrates the scores and categories for knowledge, attitude and barrier. As seen in table, the majority of responders (76.7%) have a knowledge score less than 50% with mean 8.2 (2.9) out of 26. Positive attitude was noticed for almost 93% of responders with a mean 17.46 (5.9) out of 28. The percentage of responders who perceived barrier versus perceived no barriers were almost closed to each other (41.5% vs 48.1%).

Table 2. The groups and categories for knowledge, attitude and barrier points.

Results for knowledge

Despite that 65.1% claimed perceived good–excellent knowledge about breast cancer, only 23.1% (n: 141) had a knowledge score equal to or more than 50%. However, the vast majority of pharmacists correctly identified breast cancer as the most common cancer among females (87.4%). As seen in , there were obvious variances among each knowledge sector (prevalence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, screening methods and treatment). The best-reported knowledge domain was the sign and symptoms, where the majority of pharmacists had identified the correct signs and symptoms for 3 out of 4 statements in that domain; nipple discharge (75.9%), change in breast shape (84%), and pain in breast region and dimpling (77%). This was followed by correctly identifying risk factors such as using hormone replacement therapy (77%), being old age (81.7%), and having a family history (82.1%). It was noticed when the correct answer was (false) most pharmacists failed to identify it, for example only 7.9% identify the correct answer for the statement (to detect the presence of breast cancer, women aged 40 years and above should do a monthly breast self-examination, an annual clinical breast examination, and a biannual mammogram), only 12.6% identify the correct answer for (to detect the presence of breast cancer, women over the age of twenty and under the age of forty should do a breast self-examination at least once per year), and only 14.5% get the correct answer for statement (late-onset menstrual period is one of the risk factors for developing breast cancer).

Table 3. Responses of the community pharmacists on the 26-item knowledge test on the prevalence, risk factors, signs and symptoms, screening methods, and treatment of breast cancer.

Results for attitude

There was a common notice that a positive attitude is more than a negative. Across all questions, more than 70% of the pharmacists responded to each question with agreeing or strongly agreeing. This resulted in a positive attitude score for 92.7% of the participated pharmacists. Amazingly, the positive attitude of pharmacists was not associated with the level of knowledge, in which the attitude score demonstrated no association with the knowledge score (χ2 [3.8]; p = 0.15). As seen in , the vast majority (84.6%) of the pharmacists agreed that they should be involved in breast cancer health promotion activities in the pharmacy, 82.1% agreed that the distribution of breast cancer educational materials is important in the pharmacy, 81.7% agreed that discussing breast cancer awareness is beneficial and can save female's lives.

Table 4. Responses of the pharmacists on the belief statements with regard to providing advice to patients on breast cancer.

The weakest attitude was noted in response to the statement “I feel confident and prepared to provide breast cancer health promotion”. However, even for this question particularly, the specific attitude for answering the question was not associated with the score of participant knowledge (χ2(4) = 2.9; p = 0.57).

Results for barriers

Unlike attitude, pharmacists perceived barriers in various ways. The agreement on barriers was ranged from 19.2% to 56.7%. As seen in , the strongest barrier as perceived by pharmacists was having access to breast cancer educational materials (agreed by 56.7%), followed by having enough time to provide breast cancer health promotion to patients visiting the pharmacy and having enough space to provide breast cancer health promotion to patients visiting the pharmacy (agreed by 51.4% and 51.2%, respectively). Amazingly, only 19.2% agreed that patients do not appreciate the pharmacist's role as a breast cancer health promoter, which means that patients' appreciation is not a barrier. In a similar context, pharmacists' reimbursement and patients' offense were not perceived as barriers, i.e., only 23% and 23.5% of pharmacists consider reimbursement and offended patients as barriers.

Table 5. Barrier to providing breast cancer health promotion to patients visiting the pharmacy.

A sum-up of barrier score revealed that 48.1% (i.e., barrier score was negative) of pharmacists do not have a strong barrier to delivering breast cancer care, while 41.5% (i.e., barrier score was positive) of pharmacists claim barrier that prevents them to deliver the service. 10.4% would have a balance status (i.e., barrier score was zero). Contingency table analysis showed that pharmacists with a knowledge score of more than 50% perceived higher levels of total barrier score compared with pharmacists who had a knowledge score of less than 50% (55.3% vs 37.3%, p < 0.001). The more knowledge the more realization of the barriers. Analysis showed also that perceived barriers had no association with attitude (p = 0.6), despite perceived barriers most pharmacists (92.7%) have a positive attitude toward delivering services. Attitudes did not impact the perceived barriers.

Univariate analysis for association with Knowledge score

shows that most demographic factors have a statistically significant association with the knowledge score. Accordingly, strength of association was used to get a better understanding of the association, and more impactful a stepwise backward multivariable logistic regression was carried out. The strongest and statistically significant association was noticed between knowledge score and the number of pharmacists in the pharmacy, i.e., having 1 pharmacist scored a higher percentage of knowledge score (>50%) compared with pharmacy who had 2 or more pharmacists (41.5% vs 11.69%; p < 0.0001; Phi: 0.34). Most variables at the univariate level of analysis demonstrated a statistically significant association, so multivariable analysis was carried out for better interpretation. Amazingly, the perceived knowledge filled by pharmacists -i.e., self-evaluation was not associated with the knowledge score (p = 0.17), and the educational level was not associated with the knowledge score (p = 0.066).

Table 6. Associations between sociodemographic and practice variables of the pharmacists and scoring 50?% or more in the knowledge test.

Multivariate analysis for association with knowledge score

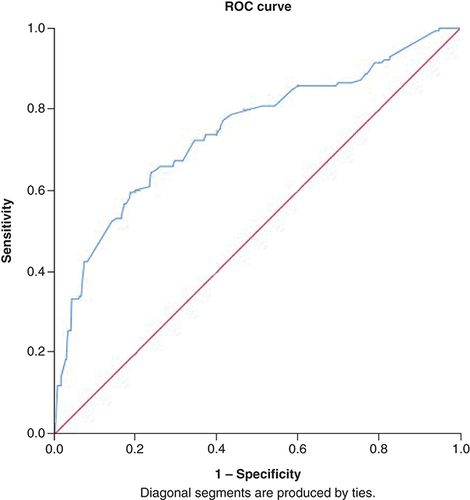

Binomial logistic regression (backward stepwise) was used to eliminate independent predictors with a non-statistically significant contribution. The best fit binomial logistic regression (backward stepwise) was a 10 steps model. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 (13) = 300.5, p < 0.0005. The model explained 52.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in knowledge score and correctly classified 80.0% of cases. Sensitivity was 35.7%, and specificity was 94.4%. The area under the ROC curve demonstrated acceptable discrimination of 74.5% (95% CI: 0.69 to 0.79, p < 0.0005), see .

ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

Only variables in were the statistically significant variables to predict the knowledge score. The following variables were considered for the first step entry: variable(s) entered on step 1: age (years), gender, marital status, education, country from where your last academic degree was obtained, experience (years), attended an educational program on breast cancer, approximate number of patients with breast cancer interacted with per month, perceived knowledge of breast cancer, average number of working h per week, average number of patients interacted with per day, percentage (%) of female patients visiting the pharmacy, number of pharmacists working in the pharmacy at any one shift [Citation34]. In addition to the answer the following statements (rarely or often): Respond to patient inquiries related to breast cancer warning signs and symptoms and breast cancer early detection and screening tests, provide patients with advice or counseling on breast cancer screening and early detection, provide patients with breast cancer educational materials or self-assessment quizzes, refer patients to special breast cancer screening programs organized by hospitals or cancer organizations. As seen in , the odds of having knowledge score >50% is 3.8 (p > 0.0001) times greater for a single pharmacist working in the pharmacy at any one shift opposed to more than two pharmacies. (OR: 3.812; 95% CI: 2.35–6.19).

Table 7. Multivariate regression analysis of the association between sociodemographic and practice variables with scoring 50?% or more in the knowledge test.

Pharmacists who often provide patients with breast cancer educational materials or self-assessment quizzes would be 2.3 (p < 0.001) times more likely to have >50% knowledge score compared with those who rarely provide such service (OR: 2.295; 95% CI: 1.41–3.75). Amazingly, with reference to analysis, pharmacists claimed attended an educational program on breast cancer or providing patients with advice or counseling on breast cancer screening and early detection were less likely to get >50% knowledge score, as ORs were 0.604 (95% CI: 0.397–0.920) and 0.305 (95% CI: 0.182–0.511); respectively.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among females worldwide [Citation40]. It represents the warning to females' health in Jordan [Citation7]. Self-examination and early screening for breast cancer diagnosis is significant to reduce morbidity and enhances the survival [Citation41]. Nevertheless, numerous studies from developing countries as well as from Jordan have revealed the low level of awareness regarding breast cancer and its screening performance [Citation42–44]. This highlights the need to broad the engagement of healthcare providers in promoting the awareness of breast cancer and its screening among public. The earlier detection of the cancer allows for the better and more effective management, unlike the disease diagnosis in advanced stages [Citation45]. Community pharmacists are accessible healthcare providers who spend long h daily in direct contact with population and are recently progressively involved in variety of healthcare protective services [Citation46,Citation47]. Accordingly, they have ideal position to be integrated in promoting breast cancer health and awareness among women in community [Citation32]. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and barriers of pharmacists in Jordan toward breast cancer health promotion. In addition, to highlight the gaps in some areas related to community pharmacists' awareness and perception in regard to breast cancer.

The questionnaire in this study was revalidated using Cronbach's alpha that showed an excellent reliability before it was distributed [Citation48]. The sampling strategy is tried to include representative participants of community pharmacists in Jordan with both genders, various ages, education levels attained, and years of experience. As well, the questionnaire asked about participants perceived knowledge about breast cancer and asked about their practice toward patient-focused breast cancer awareness and counselling of early detection. This sample diversity might add validity and rigor to the obtained results in the study.

The key findings of this study indicate that the majority of participants lack sufficient knowledge about breast cancer as 76.9% participants had knowledge score less than 50. These results are consistent with data obtained in previous study in Jordan [Citation32]. In contrast, the overall knowledge score was higher among community pharmacists in Qatar (50%) [Citation49] and Palestine (63%) [Citation50]. However, the vast majority of pharmacists correctly identified breast cancer as the most common cancer among females (87.4%). This finding matches those observed in earlier study that was conducted before 7 years in Jordan [Citation51]. Most of community pharmacists in this study lack sufficient breast cancer particularly risk factors. They have shown lack of sufficient knowledge about breast cancer risk factors, in which they have a higher emphasis on genetic are hereditable causes [Citation52]. While less than 50% of participants recognized the modifiable risk factors as cigarette smoking [Citation53] and oral contraceptives [Citation54] as potential risks and contribute to inferior prognosis. These results are in agreement with those obtained by previous research [Citation55]. Moreover, community pharmacists were knowledgeable of the benefits of early screening in reducing breast cancer prognosis. However, knowledge gaps were recognized with mammography procedure, specifically, the female's age needs to conduct breast self-examination and mammography as this has been reported previously [Citation49]. Although continuous efforts executed to increase public females' awareness regarding breast cancer, the screening level stays low [Citation56]. Previous studies reported that healthcare providers orientation and attitude are pivotal factors to increase public awareness for early breast cancer screening programs [Citation57,Citation58]. This proves the need to involve healthcare providers in increasing patient breast cancer awareness for self-examination and encourage screening [Citation55,Citation59]. It is worthy to mention that patients' decision/choice in self-care is also a contributing factor to improve health outcomes [Citation60]. Thus, it is crucial to improve community pharmacists' knowledge with regard to breast cancer screening recommendations by increasing the continuous educational programs organised by professional associations and encourage them to attend these activities [Citation27]. In addition, previous studies have reported the orientation and attitude of healthcare providers have a great influence on women's awareness for early detection of the disease by screening methods [Citation61]. Meanwhile, adoption of the oncology courses in pharmacy curriculum of undergraduate students would improve the roles for graduated pharmacists in raising the awareness and engagement in the screening programs [Citation62,Citation63]. Knowledge gaps regarding breast cancer treatment modalities were indicated in this study (less than 50% of pharmacists identified the adverse effects of breast cancer) and as similar gaps was reported in previous studies in Qatar [Citation49] and Palestine [Citation50].

The overall knowledge score was significantly associated with participant's gender, age, years of experience, and the place from where the academic degree was gained, which was consistent with previous study [Citation50]. The most interesting finding was pharmacists who often provided patients with breast cancer educational materials or self-assessment quizzes were more likely to have >50% knowledge score compared with those who rarely provide such service. Because, presence of educational materials in community pharmacies is beneficial to increase public awareness about breast cancer and support the pharmacist's role in breast cancer heath care promotion [Citation28,Citation55]. However, the contributions of pharmacist to promote public health issues are not widely reported, which may be partially due to some of their services goes unnoticed [Citation64]. Furthermore, pharmacists spend much time to fulfill their responsibilities during working h such as dispensing, supplying, and management activities, and have no enough time for delivering professional pharmacy services [Citation65]. More important, community pharmacists encounter numerous management challenges that would distract them from providing additional professional services [Citation66].

In this study, community pharmacists showed positive attitude to be involved in breast cancer health promotion activities and to provide breast cancer educational materials in pharmacies [Citation67]. While the key barrier that limits them to contribute in breast cancer education is lacks to get access to breast cancer educational materials as previously reported by community pharmacists in Qatar [Citation49]. Therefore, cancer organizations should be encouraged to provide community pharmacies with printed educational materials pertained to breast cancer for public distribution [Citation7,Citation68]. This study indicated that pharmacists' knowledge of breast cancer and its screening methods are positively associated with the involving attitude in breast cancer promotion among pharmacists [Citation69]. In this part, it is responsibility of pharmacists to take a pivotal role in breast cancer health education in community [Citation31], as they have the potential to promote public health issues [Citation64].

Jordan is considered a medium-income country with a population of young structure [Citation70], and most of the patient are presented with progressive stages of breast cancer and more aggressive tumors type [Citation71]. Accordingly, breast cancer adds more burden on the country's healthcare system. Therefore, much works and efforts should be focused on improving the access, awareness, and participation role of pharmacist in early detection to down-stage of breast cancer cases [Citation7]. Jordan is considered the training center for healthcare professions in the region [Citation70]. Nevertheless, much efforts are needed to improve breast cancer health promotion at both public and private levels and leaving pharmacy role with an incredible opportunity to extend. Accordingly, government and pharmacy governing bodies should work together to widen the scope of pharmacy practice and to extend the role of community pharmacists [Citation72]. Additionally; pharmacists need to take responsibility for advocating the pharmacy as a profession and support the patient advocacy through build interactions and partnerships with patients for follow-up care [Citation72]. Importantly, improving communication and social skills of community pharmacists with patients and other healthcare provider. This can be attained via universities which could offer a training course for students who are willing to work in community pharmacies. This would allow future students to achieve the practice of the profession in the community pharmacy in more efficient and appropriate way [Citation63].

Limitation of the study

The detailed information about breast cancer-specific education topics and training methods for the pharmacists was not obtained, as well as the patients and decision makers' opinions were not collected in this study. Therefore, further studies about breast cancer-specific education topics and on opinions of breast cancer patients and decision makers in health authorities in Jordan are recommended to mitigate existing misinterpretations and bridge knowledge gaps altogether.

Conclusion

The present study indicates significant implications for pharmacist's knowledge toward key issues of breast cancer health promotion in Jordan. The findings show that most pharmacists in Jordan are lack sufficient knowledge about breast cancer and lack the access to educational materials about breast cancer health promotion. Importantly, it highlights the positive preparedness of pharmacists in Jordan to educating themselves about breast cancer and support incorporation of the educational program in the curriculum of university pharmacy school.

Up to my knowledge, no studies have been set out to explore further gaps, improvements, and subtle changes over time of community pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, and barriers toward health promotion of breast cancer in Jordan especially after COVID-19 pandemic, and their role in promoting the health of patients with breast cancer visiting the pharmacies.

Recommendation

Future research are encouraged in Jordan to assess the views and knowledge of patients and different healthcare providers about breast cancer promotion. This has the potential to alleviate existing misunderstandings about promotion of breast cancer health key issues and bridge knowledge gaps from different healthcare providers and patients altogether.

The objective of this study was to assess pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, and barriers toward breast cancer health promotion among community pharmacists.

An internet-based self-administrated questionnaire was rolled out using social media groups to the community pharmacists in Jordan.

A 76.7% of the pharmacists had insufficient knowledge score of breast cancer and 92.7% had positive attitude. Access to breast cancer educational materials was the major barrier to pharmacists. A significant association was found between pharmacists' knowledge and breast cancer educational materials being given to patients (p < 0.001).

This research detects some predictors for breast cancer knowledge amid contributed pharmacists.

This study identifies the significance to initiate educational courses and to improve the access to educational material for community pharmacists about breast cancer health to increase public awareness to health services provided by pharmacists.

Despite the low breast cancer knowledge score and stated barriers that could prevent actualizing community pharmacists' role, they had positive attitude toward educating patients about breast cancer health.

The outcomes of this research support the essential for conducting further studies on identifying the approaches to integrating community pharmacists in the team of healthcare provider for breast cancer patients, overcoming all stated barriers, and to evaluate the knowledge and views of different healthcare providers and patients about breast cancer promotion are encouraged to improve the positive promotion and awareness of healthcare of breast cancer.

Author contributions

M Oqal designed the study, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. M Odeh performed statistical analysis, interpreted the data and wrote the results. R Abudalu wrote the discussion. A Alqudah wrote the methods. A Al-Roaa Alnajjar interpreted the raw data and helped in collecting the data from respondents. YB Younes, M Al-Shawabkeh and L Taha helped in collecting the data from respondents. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board at the Hashemite University in Jordan (no.: 4/5/2021/2022).).

Data sharing

The link for the questionnaire: https://www.dropbox.com/s/24h3uj2hb3m1ocx/Assessing%20Knowledge%20Questionnaire.doc?dl=0

Acknowledgments

The authors of the study would like to thank all the participants for their support.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was financially supported by The Hashemite University. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- BrayF , FerlayJ , SoerjomataramI , SiegelRL , TorreLA , JemalA. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.68(6), 394–424 (2018).

- AlexandrovLB. Understanding the origins of human cancer. Science (New York, N.Y.)350(6265), 1175 (2015).

- BertramJS. The molecular biology of cancer. Mol. Aspects Med.21(6), 167–223 (2000).

- SopikV. International variation in breast cancer incidence and mortality in young women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.186(2), 497–507 (2021).

- JonesAL. Fertility and pregnancy after breast cancer. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland)15(Suppl. 2), S41–S46 (2006).

- SungH , FerlayJ , SiegelRLet al.Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(3), 209–249 (2021).

- Abdel-RazeqH , MansourA , JaddanD. Breast Cancer Care in Jordan. JCO Glob. Oncol.6, 260–268 (2020).

- Ministry of Health. Information and research report (2014). www.moh.gov.jo/Echobusv3.0/SystemAssets/2d0cc71d-d935-4d6f-a72c-73d60cd0a16c.pdf

- FanL , Strasser-WeipplK , LiJJet al.Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol.15(7), e279–e289 (2014).

- DinegdeNG , DemieTG , DiribaAB. Knowledge and Practice of Breast Self-Examination Among Young Women in Tertiary Education in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Breast Cancer (Dove Medical Press)12, 201–210 (2020).

- BrentnallAR , WarrenR , HarknessEFet al.Mammographic density change in a cohort of premenopausal women receiving tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention over 5 years. Breast cancer research: BCR22(1), 101 (2020).

- GabrielsonM , AzamS , HardellEet al.Hormonal determinants of mammographic density and density change. Breast Cancer Research: BCR22(1), 95 (2020).

- GuX , WangB , ZhuHet al.Age-associated genes in human mammary gland drive human breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Research: BCR22(1), 64 (2020).

- SmithRA , AndrewsKS , BrooksDet al.Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin.69(3), 184–210 (2019).

- CalipGS , XingS , JunDH , LeeWJ , HoskinsKF , KoNY. Polypharmacy and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice13(5), e451–e462 (2017).

- KoskanAM , DominickLN , HelitzerDL. Rural Caregivers' Willingness for Community Pharmacists to Administer the HPV Vaccine to Their Age-Eligible Children. Journal of Cancer Education: the Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education36(1), 189–198 (2021).

- LewYL , IsmailF , AbdulAziz SA , MohamedShah N. Information Received and Usefulness of the Sources of Information to Cancer Patients at a Tertiary Care Centre in Malaysia. Journal of Cancer Education: the Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education36(2), 350–358 (2021).

- TanakaK , HoriA , TachiTet al.Impact of pharmacist counseling on reducing instances of adverse events that can affect the quality of life of chemotherapy outpatients with breast Cancer. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Care and Sciences4, 9 (2018).

- SchulzM , Klopp-SchulzeL , KeilhackS , MeyerS , BotermannL , KloftC. Adherence to tamoxifen in breast cancer patients: what role does the pharmacist play in German primary care?Canadian Pharmacists Journal: CPJ; Revue des pharmaciens du Canada: RPC152(1), 28–34 (2019).

- HumphriesB , CollinsS , GuillaumieLet al.Women's Beliefs on Early Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Theory-Based Qualitative Study to Guide the Development of Community Pharmacist Interventions. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland)6(2), (2018).

- PeriasamyU , MohdSidik S , RampalL , FadhilahSI , Akhtari-ZavareM , MahmudR. Effect of chemotherapy counseling by pharmacists on quality of life and psychological outcomes of oncology patients in Malaysia: a randomized control trial. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes15(1), 104 (2017).

- BarakatH , SabriN , SaadA. Prediction of chemotherapy prescribing errors for oncology patients. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research7(8), 3274 (2016).

- MostafaLS , SabriNA , El-AnwarAM , ShaheenSMJJoPH. Evaluation of pharmacist-led educational interventions to reduce medication errors in emergency hospitals: a new insight into patient care. J. Public Health (Oxf)42(1), 169–174 (2020).

- LuisettoM , CariniF , BolognaG , Nili-AhmadabadiB. Pharmacist Cognitive Service and Pharmaceutical Care: Today and Tomorrow Outlook. Pharmaceutical and Biosciences Journal3(6), 67–72 (2015).

- PruittL , MumuniT , RaikhelEet al.Social barriers to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in patients presenting at a teaching hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. Global Public Health10(3), 331–344 (2015).

- GilesJT , KennedyDT , DunnEC , WallaceWL , MeadowsSL , CafieroAC. Results of a community pharmacy-based breast cancer risk-assessment and education program. Pharmacotherapy21(2), 243–253 (2001).

- BeshirSA , HanipahMA. Knowledge, perception, practice and barriers of breast cancer health promotion activities among community pharmacists in two Districts of Selangor state, Malaysia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP13(9), 4427–4430 (2012).

- ObeidatNA , HawariFI , AmarinR , AltamimiBA , GhonimatIM. Educational Needs of Oncology Practitioners in a Regional Cancer Center in the Middle East-Improving the Content of Smoking Cessation Training Programs. Journal of Cancer Education: the Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education32(4), 714–720 (2017).

- MensahKB , BangaleeV , OosthuizenF. Assessing Knowledge of Community Pharmacists on Cancer: A Pilot Study in Ghana. Frontiers in Public Health7, 13 (2019).

- ElHajj MS , HamidY. Breast cancer health promotion in Qatar: a survey of community pharmacists' interests and needs. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy33(1), 70–79 (2011).

- ShawahnaR , AwawdehH. Pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers toward breast cancer health promotion: a cross-sectional study in the Palestinian territories. BMC Health Services Research21(1), 429 (2021).

- AyoubN , NuseirK , OthmanA , AlkishikS. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers towards breast cancer health education among community pharmacists. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research7(3), 189–198 (2016).

- ShawahnaR , AwawdehH. Pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers toward breast cancer health promotion: a cross-sectional study in the Palestinian territories. BMC Health Services Research21(1), 429 (2021).

- AyoubN , Al-TaaniG , AlmomaniBet al.Knowledge and Practice of Breast Cancer Screening Methods among Female Community Pharmacists in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Breast Cancer2021, 1–13 (2021).

- AltmanDG. statistical in medical research. DouglasG., Altman. Practical statistics for medical research.Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, NY USA (1990).

- RoystonP , MoonsKG , AltmanDG , VergouweY. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)338, b604 (2009).

- AltmanDG , VergouweY , RoystonP , MoonsKG. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)338, b605 (2009).

- KumarR , IndrayanA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for medical researchers. Indian Pediatr.48(4), 277–287 (2011).

- DeLongER , DeLongDM , Clarke-PearsonDL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics44(3), 837–845 (1988).

- BrayF , FerlayJ , SoerjomataramI , SiegelRL , TorreLA , JemalA. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.68(6), 394–424 (2018).

- ElmoreJG. Screening for Breast Cancer. JAMA293(10), 1245 (2005).

- Abu-HelalahMA , AlshraidehHA , Al-SerhanA-AA , KawaleetM , NesheiwatAI. Knowledge, barriers and attitudes towards breast cancer mammography screening in Jordan. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention16(9), 3981–3990 (2015).

- AhmedBaA. Awareness and practice of breast cancer and breast-self examination among university students in Yemen. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP11(1), 101–105 (2010).

- Al-HussamiM , ZeilaniR , AlKhawaldehOA , AbushaikaL. Jordanian Women's Personal Practices Regarding Prevention and Early Detection of Breast Cancer. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge25(3), 189–194 (2014).

- WangL. Early Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Sensors17(7), 1572 (2017).

- CalisKA , HutchisonLC , ElliottMEet al.Healthy People 2010: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action for America's pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy24(9), 1241–1294 (2004).

- HassaliM , AwaisuA , ShafieA , SaeedM. Professional training and roles of community pharmacists in Malaysia: views from general medical practitioners. Malaysian Family Physician: the Official Journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia4(2-3), 71 (2009).

- TavakolM , DennickR. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. International Journal of Medical Education2, 53 (2011).

- ElHajj MS , HamidY. Breast cancer health promotion in Qatar: a survey of community pharmacists' interests and needs. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy33(1), 70–79 (2011).

- ShawahnaR , AwawdehH. Pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers toward breast cancer health promotion: a cross-sectional study in the Palestinian territories. BMC Health Services Research21(1), 1–14 (2021).

- AyoubNM , NuseirKQ , OthmanAK , AbuAlkishik S. Knowledge, attitudes and barriers towards breast cancer health education among community pharmacists. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research7(3), 189–198 (2016).

- ShiovitzS , KordeLA. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann. Oncol.26(7), 1291–1299 (2015).

- JonesME , SchoemakerMJ , WrightLB , AshworthA , SwerdlowAJ. Smoking and risk of breast cancer in the Generations Study cohort. Breast Cancer Research19(1), 1–14 (2017).

- BardaweelSK , AkourAA , Al-MuhaissenS , AlSalamatHA , AmmarK. Oral contraceptive and breast cancer: do benefits outweigh the risks? A case-control study from Jordan. BMC Women's Health19(1), 1–7 (2019).

- MensahKB , MensahABB , BangaleeV , OosthuizenF. Awareness is the first step: what Ghanaian community pharmacists know about cancer. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice27(6), 1333–1342 (2020).

- Al-NajarMS , NsairatA , NababtehBet al.Awareness About Breast Cancer Among Adult Women in Jordan. SAGE Open11(4), 21582440211058716 (2021).

- IbrahimNA , OdusanyaOO. Knowledge of risk factors, beliefs and practices of female healthcare professionals towards breast cancer in a tertiary institution in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Cancer9(1), 1–8 (2009).

- GhanemS , GlaouiM , ElkhoyaaliS , MesmoudiM , BoutayebS , ErrihaniH. Knowledge of risk factors, beliefs and practices of female healthcare professionals towards breast cancer, Morocco. Pan African Medical Journal10, 21 (2011).

- GilesJT , KennedyDT , DunnEC , WallaceWL , MeadowsSL , CafieroAC. Results of a community pharmacy-based breast cancer risk-assessment and education program. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy21(2), 243–253 (2001).

- RajiahK , SivarasaS , MaharajanMK. Impact of Pharmacists' Interventions and Patients' Decision on Health Outcomes in Terms of Medication Adherence and Quality Use of Medicines among Patients Attending Community Pharmacies: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health18(9), (2021).

- AkhigbeAO , OmuemuVO. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian urban city. BMC Cancer9(1), 1–9 (2009).

- AlsarairehA , DarawadMW. Impact of a Breast Cancer Educational Program on Female University Students' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices. J. Cancer Educ.34(2), 315–322 (2019).

- SvensbergK. Facilitators and Barriers to Pharmacists' Patient Communication: The Pharmacist Profession, the Regulatory Framework, and the Pharmacy Undergraduate Education. (2017).

- MohiuddinAK. The Excellence of Pharmacy Practice. Innovations in Pharmacy11(1), (2020).

- KariaA , NormanR , RobinsonSet al.Pharmacist's time spent: Space for Pharmacy-based Interventions and Consultation TimE (SPICE)-an observational time and motion study. BMJ Open12(3), e055597 (2022).

- KhoBP , HassaliMA , LimCJ , SaleemF. Challenges in the management of community pharmacies in Malaysia. Pharmacy Practice15(2), 933 (2017).

- BeshirSA , HanipahMA. Knowledge, perception, practice and barriers of breast cancer health promotion activities among community pharmacists in two Districts of Selangor state, Malaysia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention13(9), 4427–4430 (2012).

- BasuP , ZhangL , HariprasadR , CarvalhoAL , BarchukA. A pragmatic approach to tackle the rising burden of breast cancer through prevention & early detection in countries ‘in transition’. The Indian Journal of Medical Research152(4), 343–355 (2020).

- UygunA , CaliskanND , TezcanS. Community Pharmacists' Knowledge on Cancer and Screening Methods. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 10781552211073822 (2022).

- BashetiIA , MhaidatNM , AlqudahR , NassarR , OthmanB , MukattashTL. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Jordan. Pharmacy Practice18(4), 2184 (2020).

- ArqoubK , AlNsour M , Al-NemryO , Al-HajawiB. Epidemiology of breast cancer in women in Jordan: patient characteristics and survival analysis. East Mediterr. Health J.16, 1032–1038 (2010).

- BoechlerL , DespinsR , HolmesJet al.Advocacy in pharmacy: changing “what is” into “what should be”. Canadian Pharmacists Journal: CPJ : Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada : RPC148(3), 138–141 (2015).