Abstract

Aim: This study examines the changes in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptom frequency among patients with GERD throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: A structured questionnaire was distributed among 198 GERD patients. The questionnaire consisted of a demographic characteristic assessment, the GerdQ questionnaire, and a reflux symptom index (RSI) questionnaire. Result & conclusion: A statistically significant increase in GerdQ score was identified among participants during the COVID-19 pandemic (t = 7.055, df = 209, p < 0.001), who had experienced an increase in the frequency of positive predictors of GERD and a decrease in the frequency of negative predictors of GERD. The COVID-19 pandemic and its related lockdown countermeasures may have led to exacerbating and worsening GERD symptoms.

Plain Language Summary

There is a lack of decisive research into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdown countermeasures on patients with GERD. We investigated the changes in symptomatic frequency among GERD patients in Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic in a cross-sectional study involving 198 GERD patients. A statistically significant number of participants experienced an increase in the frequency of positive predictors of GERD, and a decrease in the frequency of negative predictors of GERD. In addition, the impacts of GERD itself were also found to have increased during the pandemic, with patients struggling to sleep or attain additional medication to treat their condition.

The virus underlying COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, has caused over 98 million confirmed cases and 2.2 million deaths since January 2020. SARS-CoV-2 induces a severe acute respiratory syndrome by entering the cells of an infected individual mainly via the ACE2 cell receptors [Citation1–4].

Previous studies have shown that the oral and nasal mucosa, the nasopharynx, the esophagus, the lung, the small intestine, the colon, the kidney, the spleen, the liver, and the brain all contain ACE2 [Citation3,Citation4]. In addition, it has been observed that ACE2 expression is around 100-fold greater in the digestive system than in the respiratory system [Citation5]. Since there are a number of ACE2-expressing organs in the digestive tract, it stands to reason that SARS-CoV-2 [Citation6] may potentially infect these organs and influence gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidity in some way. Although fever, cough, and dyspnea are the most common symptoms associated with COVID-19 [Citation7], patients with a clinically significant subgroup of COVID-19 also report GI problems, which are commonly accompanied by increased liver enzymes [Citation8]. COVID-19 has been observed to manifest first as GI symptoms in some patients [Citation9]. These results imply that the virus may affect the digestive tract, which may account for the wide variety of GI symptoms seen in COVID-19.

“Comorbidity” refers to any long-term health condition that coexists in an individual with a specific condition of interest; the importance of comorbidity in modifying severity and outcomes in COVID-19 was recognized in the earliest scientific reports [Citation10]. Diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and a history of ischemic heart disease were often reported as co-morbidities among the COVID-19 patients [Citation11]. One such group of comorbidity are those who have diseases and symptoms related to the GI tract, which have been found to increase with the COVID-19 pandemic by a number of epidemiological studies [Citation12–14].

Of the various types of GI disorders, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is considered to be among the most common, caused by a backflow of stomach contents and inducing symptoms and complications in that region that may include regurgitation and heartburn [Citation15–17]. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a variant of GERD, wherein this backflow of stomach contents reaches the laryngopharynx [Citation18]. The distinction between LPR and GERD has become increasingly more defined over the last 25 years, with patients with LPR presenting unique symptoms, reflux patterns, and responses to treatment than their counterparts with GERD [Citation18].

Increased risk for GERD has been associated with lifestyle variables such as being overweight, low level of physical activity, dietary habit, smoking, alcohol intake and sleeping posture [Citation19]. Increased intake of fatty meals and certain beverages, such as tea, coffee, and fizzy drinks, are dietary contributors [Citation20]. Quality of life, job performance, and sleep are all negatively impacted by GERD [Citation21,Citation22]. In addition, research shows that it has serious economic consequences [Citation23].

Though further research is needed, observational links have already been drawn between GERD and COVID-19. Both diseases share similar major risk factors, such as obesity and smoking [Citation24], and develop similar symptoms among patients [Citation25]. A genetic correlation has also been found between patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and their susceptibility to GERD, as shown by Mendelian randomization findings that have suggested a causal link between the two diseases [Citation26]. The prevalence of GERD increased from 24.8% before the pandemic to 34.2% during the pandemic, according to research conducted in Saudi Arabia [Citation27]. There was an increase in the severity of GERD symptoms during the epidemic as well as increase the frequency of administration of GORD medications [Citation27].

Despite the large body of research already existing on the negative impacts of lockdown countermeasures to COVID-19 on the health of patients suffering from chronic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, and a range of mental health issues and disorders as well [Citation28,Citation29]. To our knowledge, only a few of the previous studies [Citation26,Citation27] exist that seek to address the same impacts on patients suffering from GERD. This study therefore aims to rectify this absence of literature by taking the following steps: 1) assessing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdown countermeasures on patients suffering from GERD; and 2) determining the prevalence of LPR among patients diagnosed with GERD, taking the country of Jordan as a geographic basis for this study. If a link were to exist between GERD and COVID-19, we might expect to find a correlated increase or decrease in GERD symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is therefore hoped that this study might provide a complementary perspective on what links these diseases, if indeed such a link exists and may be identified.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was undertaken with structured questionnaires distributed among known cases of GERD patients who attend the upper GI clinic at Prince Hamza Hospital. From January through May of 2021, data was gathered during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country of Jordan. A second, more intense wave of COVID-19 transmission, prompted by the quickly dispersing UK strain, started around the middle of January, and peaked around the middle of March of the same year [Citation30].

All patients with confirmed GERD who attend the upper GI clinic at Prince Hamza Hospital for follow-up and medication were approached. Each patient's medical history is reviewed before to enrollment to confirm the diagnosis of GERD, which is often achieved by a combination of clinical symptoms, responsiveness to acid suppression, and objective testing using upper endoscopy and esophageal pH monitoring.

In this study, we included adults aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with GORD. Patients with previous GI surgery or malignancy, mental illness, who did not give their consent and were less than 18 years old, were excluded. Pregnant females were also excluded. Patients who had been previously infected with SARS-coV- virus in the past 2 months were excluded from this study as this study explored the impact of the pandemic and its lockdown countermeasures on patients suffering from GERD. All eligible patients who signed a permission form were interviewed, their hospital stays were monitored, and their data was included in the study.

Potential participants met with a research assistant and were given information related to the research. They were assured that the data they provided would remain strictly confidential and would only be shared among study conductors and that no personal information would be required of them. Potentially all patients from the population of the regional clinic who visited the clinic while the research was being conducted were contacted (there were a total of 238), and we were able to enroll 83.5% of all the eligible patients. 198 patients answered the questionnaire, all of whom were adults who had been diagnosed with GERD in the past and who took regular dosages of proton pump inhibitors to ameliorate the symptoms of their condition.

Data collection methods

An online self-administered questionnaire used by this study for data collection was distributed via WhatsApp among participants and validated in a pilot study of 21 participants (the responses of which have been excluded from subsequent analysis). The questionnaire consisted of three parts:

The first section of the questionnaire acted as a preliminary means of assessing demographic characteristic of the participants and asked questions pertaining to each participant's age, gender, marital status, tobacco and alcohol use, as well as their height (in meters) and weight (in kilograms) with which to determine their BMI (kg/m).

The second section of the questionnaire pertaining to GerdQ scores () requested that participants score the occurrence of their symptoms over a week as well as detail any medications they had taken within this period. A four-point graded Likert scale (0–3) was used to score the frequency of four specific positive predictors, those being heartburn, regurgitation, sleep disturbance owing to reflux symptoms, and the frequency of over the counter (OTC) medication usage to counteract reflux symptoms. A 4-point graded reversed Likert scale (3–0) was also used to score the frequency of two specific negative predictors, epigastric pain and nausea. Numerical responses to these answers allowed for a total GerdQ score ranging from 0 to 18. Qualifiers pertaining to sleep disturbance and OTC medication usage were also used to assess the impact of GERD on each participant, providing a separate ‘impact score’ ranging from 0 to 6. The GerdQ questionnaire was found to have a sensitivity of 65% and a specificity of 71% for the accurate diagnosis of GERD [Citation31]. Participants must provide two answers to each question within its second section pertaining to GerdQ scores; the first to reflect their status prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the second to reflect their status in the present and moment of their response.

Table 1. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire (GerdQ).

The third section of this questionnaire included the reflux symptom index () that was used in order to assess the presence and intensity of commonly reported LPR symptoms [Citation32]. This index allows participants to grade their experiences on a 0–5 scale, with 0 describing minimal or non-existent symptoms and 5 describing severe and pronounced symptoms. This index was used to gather a range of symptoms, with participants asked to respond to the following list of complaints: hoarseness or a problem with your voice; clearing your throat; excess throat mucus or postnasal drip; difficulty swallowing food, liquids, or pills; coughing after you ate or after lying down; breathing difficulties or choking episodes; a troublesome or annoying cough; sensations of something sticking in your throat or a lump in your throat; and heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up. Scores greater than 13 were considered clinically and statistically significant as indicators of LPR [Citation33]. This index scored highly in both test-retest reliability (rs = 0.921) and internal consistency reliability (α = 0.969) [Citation34].

Table 2. The reflux symptom index .

Statistical analysis

GraphPad InStat 6.0 was used to analyze the data collected in this study, with descriptive measures used for categorical data, including counts and proportions presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), and percentages. The bootstrapping method calculated 95% of Cls in Cramer's V statistics. A two-sided p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant, with chi-square used to assess the significance of variables pertaining to GERD. Paired t-tests were also employed to find the differences between any two variables on the same subject.

Results & findings

Patients characteristic

As is shown in , of the 198 participants who responded to this questionnaire, 58.1% were male and 41.9% were female. Participants fell most commonly into the age bracket of 38–48 years old at 34.3%, followed by 29.8% in the bracket of 28–38, 14.1% in the bracket of 18–28, 13.6% in the bracket of 48–58, and 8.1% in the bracket of 58 and above. Regarding marital status, 60.1% reported that they were married, with the remaining 39.9% reporting that they were single or divorced. Most patients were found to be overweight, as determined by a mean BMI of 27.0 ± 4.5, while 28 (14.1%) were found to have at least one identifiable comorbid condition, the most common of which being hypertension (8.1%), diabetic mellitus (7.1%), and cardiovascular disease (6.6%). Finally, thirty-six participants (18.2%) identified themselves as nonsmokers.

Table 3. Basic demographic and medical information of the patients included in this study.

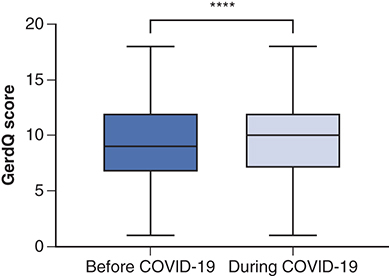

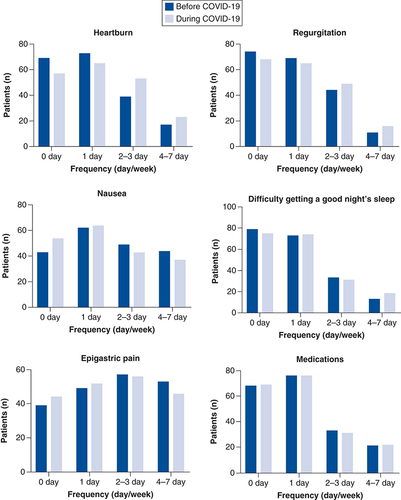

A statistically significant increase in GerdQ score was identified among participants during the period of the pandemic, as is demonstrated in (t = 7.055, df = 209, p < 0.001). demonstrates the increase in positive predictors of GERD that was identified in this study, including predictors such as heartburn and regurgitation, and the reduced frequency of counteractively negative GERD predictors. The aforementioned ‘impact score’ also demonstrated an increased impact of GERD symptoms during this period, such as through an increased reliance on medication by GERD patients and a difficulty for such patients to maintain a consistent and restful sleep cycle. As may be seen in , 8.6% of participants reported incidences of heartburn and 5.6% of regurgitation at a frequency of 4–seven-times per week prior to the pandemic. These results increased to 11.6 and 8.1%, respectively, when participants were asked to report on the frequency of these symptoms during the pandemic itself. In terms of negative predictors of GERD, 26.8% and 22.2% of participants reported incidences of epigastric pain and nausea at a frequency of 4–seven-times per week prior to the pandemic. This result decreased to 23.2% and 18.7% when participants were asked to report on the frequency of this negative predictor during the pandemic itself. Lastly, GERD patients also reported an increasingly poor quality of sleep during the pandemic, as well as an increase in the use of additional medication to combat their symptoms.

****p-value < 0.0001.

The x-axis represents the frequency of items in terms of days per week. The y-axis represents the number of patients reporting each item.

Table 4. Patient responses to GerdQ for each item in terms of the number and percentage of patients prior to COVID-19 and the changes that occurred to symptomatic frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prevalence of LPR

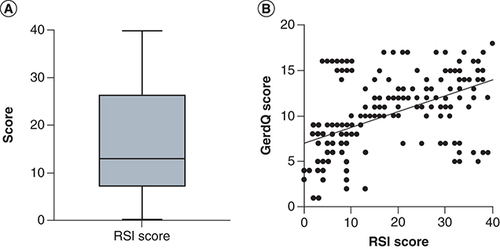

Of the 198 participants in this study, ninety-five provided responses amounting to an RSI score of more than thirteen, indicating the possible presence of LPR. RSI scores range from 0–40, with a mean score being found across all respondents of 17.1 ± 11.9 and a median score of 14.5 (A). A statistically significant positive correlation was identified between the RSI and GerdQ scores provided by participants (R = 0.49, 95% CI (0.38 to 0.59), p < 0.0001) ( B), with a mean GerdQ score of 7.8 ± 4 found among all participants with an RSI score below 13 compared with the mean GerdQ score of 11.7 ± 3.4 found among all participants with an RSI score of 13 or higher. No other social demographics or comorbid symptoms were found to be statistically significantly different between participants with an RSI score below 13 and participants with an RSI score of 13 or above ().

(A) RSI score among the participants, median = 7.0 with mean ± SD = 16.3 ± 11.4. (B) Correlation between the RSI and GerdQ scores among participants (R = 0.49, 95% CI (0.38 to 0.59), p < 0.0001).

RSI: Reflux symptom index; SD: Standard deviation.

Table 5. The difference between GERD patients who have RSI scores below 13 and those who have RSI scores greater than thirteen in terms of the GerdQ score, demographics and previous medical history.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic or the restrictive lockdown countermeasures during the pandemic on patients with GERD. This study has also sought to discuss the prevalence of LPR among the cohort of patients diagnosed with GERD in one of Jordanian hospitals. To arrive at a competent analysis of this topic, this study has gathered data from 198 residents of Jordan who have previously been diagnosed with GERD. Most of these participants had complaints about certain characteristic symptoms of GERD, including heartburn and regurgitation, which they claimed had increased in frequency throughout the length of the pandemic. Respondents also claimed that their sleep patterns had suffered because of COVID-19 and that they now relied more on other medications and increased the dose of their medications than they had prior to the lockdown. The findings of this study agree with those of Oliviero, Ruggiero, D'Antonio et al. [Citation35] and Lee, Huo, Huang [Citation36], which concluded that COVID-19 had exacerbated certain symptoms of GI in affected individuals, such as functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome.

This study has found that GERD symptoms became more frequent with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is consistent with a previous study published by Alhuzaim, Alotaibi [Citation27]. This increase in symptomatic frequency might possibly be attributed to the restricted living styles enforced by COVID-19 lockdown countermeasures and the induced behavioral shifts as a result, such as an increase in coffee ingestion and smoking, which have both been found to have occurred as a result of these measures [Citation37]. Further behavioral changes might also include increased eating and lying down or dietary changes such as consuming a larger lunch as opposed to the smaller lunches provided by offices or commercial cafes in the city [Citation38]. These dietary and behavioral changes may have had adverse effects on the reflux symptoms of GERD patients as a result [Citation39]. A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies by González-Monroy et al. [Citation40] described a certain change in the public's eating behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic toward snacking and a preference for sweets and ultra-processed food stuffs as opposed to fruits, vegetables and fresh food, with a decline in the general preference for healthy dietary behaviors in the process. The international consumption of alcohol has also been found to have increased over the course of the pandemic [Citation40], leading to this study's opinion that the general risk of reflux has increased as a predisposing factor for GERD.

It is also apparent that weight plays a fundamental mechanical role in increasing reflux symptoms among patients diagnosed with GERD [Citation41]. Previous research has found a statistically significant increase in the weight of some people during the pandemic [Citation42], with a paper by Bakaloudi et al.[Citation43] demonstrating that lockdown measures have negatively impacted the body weights of individuals across the globe. Further studies by Chang et al. [Citation44] and Pellegrini et al. [Citation45] have found a similar inclination toward higher BMI and international body weights throughout the length of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It may be posited that the influential factors behind the increase in weight and BMI around the world have also played a part in the epidemic of GERD itself. Evidence has shown that more fat-rich and substantial diets may have a certain effect on the prevalence of GERD diagnoses within a general population [Citation46]. Furthermore, high calorific diets have been shown to also increase one's exposure to esophageal acid [Citation46,Citation47]. As such, we may assume that it is likely that the same dietary habits might promote the development of both diseases. In addition, one likely explanation is that the increased weight of an individual places more substantial pressure on the abdomen [Citation48] which, in turn, may increase the risk of unwanted muscular relaxation in the lower esophageal sphincter (this is the ring of muscle between the esophagus and the stomach, known as the ‘LES’).

Furthermore, many studies demonstrated the psychological effects of mandatory quarantines during past pandemics have on people. Quarantined patients in Toronto during the 2002–2004 SARS epidemic who responded to a web-based survey by Hawryluck, Gold, Robinson, Pogorski, Galea, Styra [Citation49] indicated a significant incidence of psychological distress. During the time of isolation, 7.6% of the 1656 patients who had encountered MERS patients reported experiencing anxiety, as reported by Jeong, Yim, Song et al. [Citation50]. Recent research based on an online survey by Mazza, Ricci, Biondi et al. [Citation51] on 2766 Italians during the COVID-19 epidemic found that the acquaintance of COVID-19 infection was linked to high levels of stress. Sensitivity to reflux might be brought on by stress [Citation52]. Anxiety, especially health-related anxiety, has been shown to lower a person's pain threshold, making them more sensitive to reflux episodes [Citation53]. Another way that stress contributes to reflux is by making individuals swallow more air than usual during the day [Citation54].

This study has found that ninety-five of its 198 participants (47.9%) demonstrated an RSI score exceeding thirteen, indicating the presence of LPR. If this statistic may be extrapolated to describe the GERD population of Jordan, whereby some 1-in-2 individuals affected by GERD may also be affected by LPR, this would suggest that LPR is common and prevalent in the region and that further studies are needed for more accurate statistics. Moreover, this would also have large-ranging ramifications for both the primary and secondary care resources of the country, such as in general physician and clinic visits, treatment costs, and investigation frequency. LPR-related symptoms, which may include hoarseness and foreign body sensations in the throat, may also create a heightened sense of anxiety among patients, who may fear they have an undetected malignancy. More often than not, said individuals will be eventually referred to an otolaryngologist for diagnosis and reassurance, which - if such referrals begin to exceed nominal levels - may begin to put unwanted pressure upon Jordanian's already strained medical budget and healthcare system, when in fact these patients may simply be treated with PPI and liquid alginates instead.

Limitation

While conducting this study, we remain aware that using an RSI >13 as a diagnostic evaluation of LPR is potentially problematic. RSI may induce a number of nonspecific symptoms, such as hoarseness, coughing, throat-clearing, and a build-up of sticky mucus, that may also be related to many other common inflammatory diseases of the upper aerodigestive tract, such as allergies, rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, and pharyngolaryngitis [Citation55–57]. Diagnosing for LPR in the absence of the gold standard of either pH manometry or the combination of laryngoscopy and detected LRP symptoms therefore relies on such simplified RSI scoring systems, which is considered one limitation of this study. This limitation, while it introduced a speculative element of subjectivism to the hypothetical diagnosis of the study's respondents, is nevertheless considered the best possible approach that is usually used to separate out diagnoses of LPR from general GERD [Citation58].

Indeed, subjectivism is one of the more fundamental issues pervading this study, as it relies solely upon data gathered from the opinions and memories of its questioned individuals. Without a secondary analytical perspective gathered from a more specific investigative method, such as flexible endoscopy or ambulatory 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring, the accuracy of this study's results may also be called into question. However, as more specific investigative approaches are highly costly and invasive, they may also be considered unsuitable foruse in such a study. A third limitation of this study may be found in the size of its sample group, which may be considered relatively small. This might limit the study's generalizable capabilities to be extracted to a more international conclusion on the epidemic's impacts on GERD, such that larger studies investigating multiple treatment centers are advised to improve the validity of this study's findings on a larger scale. Finally, as this study retrieved data through a survey questionnaire, individual response and recall bias may also have played a role in the accuracy of its findings, which cannot be managed or controlled by the study's researchers. Despite these caveats, this research is one of the few to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the prevalence of GORD-19 symptoms.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study found an increase in symptomatic frequency among GERD patients, which seems to correlate with the development of the COVID-19 pandemic and its related social and legislative countermeasures, as well as the behavioral shifts that have come because of these measures as well. To further understand the pandemic's impact on GERD, we need a bigger multiregional sample. The findings of this work need to be evaluated and confirmed by future studies. This research might help gastroenterologists and other doctors to identify areas that could help in reducing the severity of GORD among population in future pandemic or other lockdown measures. Since this study identified a significant frequency of LPR among individuals diagnosed with GERD Further research is recommended to validate these results and to appropriately extrapolate them onto a broader national scale.

Previous studies have investigated the links between COVID-19 and the exacerbation of certain comorbid conditions. However, there remains a lack of decisive research into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdown countermeasures on patients suffering from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

This study therefore looks to examine the changes in symptomatic frequency among patients of GERD throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in the country of Jordan, as well as to evaluate the prevalence of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) among GERD patients in the region.

A statistically significant number of participants had experienced an increase in the frequency of positive predictors of GERD and a decrease in the frequency of negative predictors of GERD.

The impacts of GERD itself were also found to have increased during the pandemic, with patients struggling to sleep or attain additional medication for GORD.

This study concludes that the COVID-19 pandemic and its related lockdown countermeasures may have led to a change in GERD patient lifestyle, exacerbation and worsening of their symptoms as a result. Further research is needed on this subject to arrive at a more definitive result.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: H Al-momani and S Mahmoud; Methodology: D Al Balawi, M Almasri, H AlGhawrie, L Ibraheem, L Adli and H Al-momani; Software: H Al-momani; Formal analysis: H Al-momani; Investigation: H Al-momani; Writing – original draft preparation: H Al-momani; Supervision: H Al-momani; Project Administration: H Al-momani.

Ethical conduct of research

Ethical approval was provided by The Hashemite University and Prince Hamza Hospital's Ethics Service Committee for this study (reference no. 5/3/2020/2021). Participants were made aware of the study's objectives, and their consent was provided in writing. They were also informed that the information they provided would remain confidential, that their identity would not be demanded or revealed by the study; and that no personal information would be demanded or revealed either. The questionnaire provided was reviewed by relevant experts prior to its administration, and the data collected by participant's response to this questionnaire has been solely used for the purpose of this research study.

Acknowledgments

The researchers thank the participants for sharing their experience and time, without which this research would not have been possible.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Posadas-SánchezR , FragosoJM , Sánchez-MuñozFet al.Association of the transmembrane serine protease-2 (TMPRSS2) polymorphisms with COVID-19. Viruses14(9), 1976 (2022).

- MirT , AlmasT , KaurJet al.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): multisystem review of pathophysiology. Annals of Medicine and Surgery69, 102745 (2021).

- LiW , MooreMJ , VasilievaNet al.Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature426(6965), 450–454 (2003).

- HoffmannM , Kleine-WeberH , KrügerN , MüllerM , DrostenC , PöhlmannS. The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. BioRxiv1–23https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929042 (2020).

- ZhangH , KangZ , GongHet al.The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: a bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes. BioRxiv1–26https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.30.927806 (2020).

- HammingI , TimensW , BulthuisM , LelyA , NavisGJ , van GoorH. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland203(2), 631–637 (2004).

- DiaoK , HanP , PangT , LiY , YangZ. HRCT imaging features in representative imported cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Precision Clinical Medicine3(1), 9–13 (2020).

- WangM , ZhouY , ZongZet al.A precision medicine approach to managing 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Precision Clinical Medicine3(1), 14–21 (2020).

- SongY , LiuP , ShiXet al.SARS-CoV-2 induced diarrhoea as onset symptom in patient with COVID-19. Gut69(6), 1143–1144 (2020).

- SanyaoluA , OkorieC , MarinkovicAet al.Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN comprehensive Clinical Medicine2, 1069–1076 (2020).

- UmakanthanS , SenthilS , JohnSet al.The effect of statins on clinical outcome among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a multi-centric cohort study. Frontiers in Pharmacology13, 742273 (2022).

- ZaidanM , Al-HawashS , FarsakhNA-FA , KhairallahK. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) among medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study. JAP Academy Journal1(1), 1–10 (2023).

- CharpiatB , BleyzacN , TodM. Proton pump inhibitors are risk factors for viral infections: even for COVID-19?Clinical Drug Investigation40, 897–899 (2020).

- LeiH-Y , DingY-H , NieKet al.Potential effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy133, 111064 (2021).

- BredenoordAJ. Mechanisms of reflux perception in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology107(1), 8–15 (2012).

- MousaH , HassanM. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Pediatric Clinics64(3), 487–505 (2017).

- KolligsF , KurzC. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease. In: Gastroenterology For General Surgeons.Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 133–142 (2019).

- CampagnoloAM , PristonJ , ThoenRH , MedeirosT , AssunçãoAR. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: diagnosis, treatment, and latest research. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology18, 184–191 (2014).

- ArgyrouA , LegakiE , KoutserimpasCet al.Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease and analysis of genetic contributors. World journal of Clinical Cases6(8), 176 (2018).

- ZhangM , HouZ-K , HuangZ-B , ChenX-L , LiuF-B. Dietary and lifestyle factors related to gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management17, 305–323 (2021).

- KimuraY , KamiyaT , SenooKet al.Persistent reflux symptoms cause anxiety, depression, and mental health and sleep disorders in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition59(1), 71–77 (2016).

- LeeS-W , ChangC-S. Impact of overlapping functional gastrointestinal disorders on the quality of life in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility27(2), 176 (2021).

- AlqallafS , ZaidA , ShamtootA , AlhamaliA , AlzakiH. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. Japanese J Gastroenterol Res2(9), 1091 (2022).

- MonteiroAC , SuriR , EmeruwaIOet al.Obesity and smoking as risk factors for invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID-19: a retrospective, observational cohort study. PLOS ONE15(12), e0238552 (2020).

- GrantMC , GeogheganL , ArbynMet al.The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLOS ONE15(6), e0234765 (2020).

- OngJ-S , GharahkhaniP , VaughanTL , WhitemanD , KendallBJ , MacGregorS. Assessing the genetic relationship between gastro-esophageal reflux disease and risk of COVID-19 infection. Hum. Mol. Genet.31(3), 471–480 (2022).

- AlhuzaimWM , AlotaibiAT , AlruwaybiahHAet al.The prevalence and risk factors of GERD in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the impact of Covid-19 pandemic. International Research Journal of Public and Environmental Health8(5), 284–292 (2021).

- SaqibMAN , SiddiquiS , QasimMet al.Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on patients with chronic diseases. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews14(6), 1621–1623 (2020).

- TadicM , CuspidiC , ManciaG , Dell'OroR , GrassiG. COVID-19, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases: should we change the therapy?Pharmacol. Res.158, 104906 (2020).

- ArwaQ , Al-OmariM , AbbasMM , MahmoudG. Two years of COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: a focus on epidemiology and vaccination. Journal of Global Health12, 03063 (2022).

- ZhouLY , WangY , LuJJet al.Accuracy of diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease by GerdQ, esophageal impedance monitoring and histology. Journal of Digestive Diseases15(5), 230–238 (2014).

- BelafskyPC , PostmaGN , KoufmanJA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). Journal of Voice16(2), 274–277 (2002).

- SchindlerA , MozzanicaF , GinocchioD , PeriA , BotteroA , OttavianiF. Reliability and clinical validity of the Italian Reflux Symptom Index. Journal of Voice24(3), 354–358 (2010).

- LechienJR , BobinF , MulsVet al.Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom score. The Laryngoscope130(3), E98–E107 (2020).

- OlivieroG , RuggieroL , D'AntonioEet al.Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on symptoms in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders: relationship with anxiety and perceived stress. Neurogastroenterology & Motility33(5), e14092 (2021).

- LeeI-C , HuoT-I , HuangY-H. Gastrointestinal and liver manifestations in patients with COVID-19. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association83(6), 521–523 (2020).

- ĐogašZ , LušićKalcina L , PavlinacDodig Iet al.The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and mood in Croatian general population: a cross-sectional study. Croatian Medical Journal61(4), 309–318 (2020).

- MunH , SoES. Changes in physical activity, healthy diet, and sleeping time during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Nutrients14(5), 960 (2022).

- FuchsKH , BabicB , BreithauptWet al.EAES recommendations for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg. Endosc.28, 1753–1773 (2014).

- González-MonroyC , Gómez-GómezI , Olarte-SánchezCM , MotricoE. Eating behaviour changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health18(21), 11130 (2021).

- FestiD , ScaioliE , BaldiFet al.Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology15(14), 1690–1701 (2009).

- YangJ , HuJ , ZhuC. Obesity aggravates COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol.93(1), 257–261 (2021).

- BakaloudiDR , BarazzoniR , BischoffSC , BredaJ , WickramasingheK , ChourdakisM. Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on body weight: a combined systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition41(12), 3046–3054 (2021).

- ChangT-H , ChenY-C , ChenW-Yet al.Weight gain associated with COVID-19 lockdown in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients13(10), 3668 (2021).

- PellegriniM , PonzoV , RosatoRet al.Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients12(7), 2016 (2020).

- AyaziS , HagenJA , ChanLSet al.Obesity and gastroesophageal reflux: quantifying the association between body mass index, esophageal acid exposure, and lower esophageal sphincter status in a large series of patients with reflux symptoms. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery13, 1440–1447 (2009).

- FoxM , BarrC , NolanS , LomerM , AnggiansahA , WongT. The effects of dietary fat and calorie density on esophageal acid exposure and reflux symptoms. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology5(4), 439–444 (2007).

- EmerenzianiS , RescioMP , GuarinoMPL , CicalaM. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease and obesity, where is the link?World Journal of Gastroenterology19(39), 6536–6539 (2013).

- HawryluckL , GoldWL , RobinsonS , PogorskiS , GaleaS , StyraR. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis.10(7), 1206 (2004).

- JeongH , YimHW , SongY-Jet al.Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and Health38, e2016048 (2016).

- MazzaC , RicciE , BiondiSet al.A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health17(9), 3165 (2020).

- KondoT , MiwaH. The role of esophageal hypersensitivity in functional heartburn. J. Clin. Gastroenterol.51(7), 571–578 (2017).

- ThibodeauMA , WelchPG , KatzJ , AsmundsonGJ. Pain-related anxiety influences pain perception differently in men and women: a quantitative sensory test across thermal pain modalities. PAIN®154(3), 419–426 (2013).

- ConchilloJM , SelimahM , BredenoordA , SamsomM , SmoutA. Air swallowing, belching, acid and non-acid reflux in patients with functional dyspepsia. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics25(8), 965–971 (2007).

- ErenE , ArslanoğluS , AktaşAet al.Factors confusing the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux: the role of allergic rhinitis and inter-rater variability of laryngeal findings. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology271(4), 743–747 (2014).

- BrownHJ , KuharHN , PlittMA , HusainI , BatraPS , TajudeenBA. The impact of laryngopharyngeal reflux on patient-reported measures of chronic rhinosinusitis. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology129(9), 886–893 (2020).

- LechienJR , AkstLM , HamdanALet al.Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease: state of the art review. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery160(5), 762–782 (2019).

- WanY , YanY , MaFet al.LPR: how different diagnostic tools shape the outcomes of treatment. Journal of Voice28(3), 362–368 (2014).