Abstract

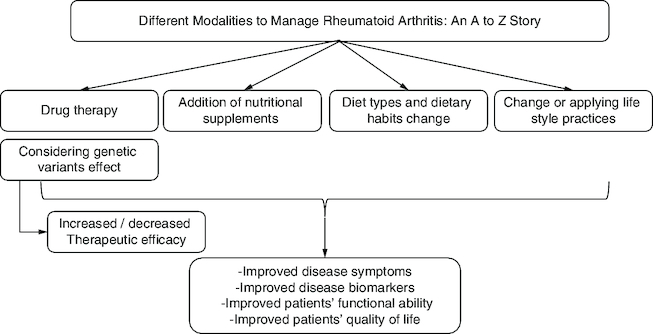

Aim: To investigate different approaches to RA treatment that might lead to greater efficacy and better safety profiles. Methods: The Search strategy was based on medical subject headings, and screening and selection were based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Results & discussion: Early therapy is critical for disease control and loss of bodily function. The most promising outcomes came from the development of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Different foods have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities that protect against the development of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Some dietary patterns and supplements have been shown to have potential protective benefits against RA. Conclusion: Improvement in the quality of life of RA patients requires a tailored management approach based on the current patient medical data.

Plain language summary

Rheumatoid arthritis is a complex disease with an unclear origin that affects the joints. In this systematic review, we aimed to investigate different effective ways of treating rheumatoid arthritis. Study results indicate that rheumatoid arthritis treatment requires coordination between different healthcare teams. As much as we can, when we start disease treatment early, this will lead to a better disease cure. Different drugs showed promising results in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, but the most promising treatment results came from a group of medicinal agents called ‘disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs’. Different foods have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect and help in protection against rheumatoid arthritis, but others, such as red meat and salt, have the opposite effect. Some dietary patterns and supplements, such as the Mediterranean Diet, vitamin D and probiotics, have been shown to have potential protective benefits against rheumatoid arthritis. Improvement in the quality of patient life requires an individualized management roadmap based on current patient medical data.

Graphical abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) care necessitates a multidisciplinary approach due to its complexity.

Early therapy is critical for disease control, prevention of joint degradation, and loss of bodily function.

Changes in gut flora and body composition are two indirect ways through which nutrition impacts the onset and course of RA.

Mediterranean Diet (MD), vitamin D, and probiotics have been shown to have potential protective benefits against RA.

Excessive red meat intake and a high total protein supply have been linked to an increased risk of inflammatory polyarthritis.

Different molecules and minerals may contribute positively to relieving RA symptoms, preventing disease progression, and enhancing the quality of life of patients.

Lifestyle choices such as sedentary behavior, poor or unhealthy diet, smoking, and alcohol consumption are all factors associated with an increased risk of acquiring comorbidities with RA.

Genetic screening in healthcare settings is important to provide patients with the most suitable therapeutic choice with minimal side effects and maximum clinical efficacy.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disorder that causes inflammatory arthritis as well as extra-articular manifestations and mostly affects synovial joints. It often begins in small peripheral joints, and it is commonly symmetric. If left untreated, it continues to affect proximal joints. Over time, joint inflammation causes cartilage and bone degradation, resulting in joint degeneration. Early RA is described as having symptoms for less than six months, while established RA is defined as having symptoms for more than 6 months [Citation1]. Most clinical signs of RA show that the wrists, metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints and metatarsophalangeal joints in the foot are always painful and swollen [Citation2].

The cause of RA is still unclear. It is hypothesized to be caused by the interplay of a patient's genetics and environment. Rheumatoid disease has a heritability of 40–65% for seropositive rheumatoid arthritis [Citation3,Citation4] and 20% for seronegative rheumatoid arthritis [Citation5]. Genetic studies showed that HLA-DRB1 alleles (HLA-DRB1*04, *01, and *10) have been linked to an increased chance of developing rheumatoid arthritis [Citation6].

Cigarette smoking is the most significant environmental risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis. There is an association between genes and smoking that raises the incidence of RA in ACPA (anti-citrullinated protein antibody)-positive persons. On the other hand, the diversity of the gut microbiome changes in RA patients (dysbiosis) shows a lower gut microbiome diversity compared with healthy individuals. Collinsella has been linked to increased RA disease severity by altering the gut mucosal permeability [Citation7].

RA generally appears between the ages of 35 and 60, with periods of remission and aggravation. It can also affect young children before the age of 16, which is known as juvenile RA (JRA), which is identical to RA except that no rheumatoid factor is present [Citation8]. JRA is divided into five subtypes which are oligoarticular, polyarticular arthritis, systemic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. The previous subtypes are seronegative except for polyarticular arthritis which may be seropositive like adults or seronegative [Citation9]. The prevalence of RA in the West is estimated to be 1–2%, with a global incidence of 1% [Citation8].

The interplay of genetic and environmental variables might cause RA in the potential trigger sites (lung, oral and gut), which is defined by the initiation of self-protein citrullination and the development of autoantibodies against citrullinated peptides [Citation10].

In observational studies, diagnosed RA patients showed a poor nutritional status [Citation11], with lower carbohydrate energy intake, higher saturated fat consumption [Citation12], and lower micronutrient intake [Citation11] compared with unaffected controls. This may contribute to the higher risk of cardiovascular diseases seen in RA patients [Citation13].

Adequate antioxidant tissue concentrations may provide an essential defense against the increased oxidative stress in RA patients. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the benefits of vitamins C and E and selenium for the treatment of RA. In general, vitamin E (α-tocopherol) insufficiency and low tissue vitamin E levels boost inflammatory response components while suppressing immune response components [Citation14].

New treatment techniques are now accessible as a result of significant breakthroughs in the pharmaceutical sector [Citation15]. Early diagnosis and appropriate nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment of RA, together with frequent monitoring of therapeutic efficacy and safety, are required for the most successful therapeutic strategy.

Treatment of RA aims to minimize joint inflammation and discomfort, improve joint function, and avoid joint deterioration and deformity. Treatment approaches include a mix of medications, weight-bearing exercise and patient education. Treatments are often tailored to the needs of the patient. It covers things like illness progression, the joints affected, age, general health, profession, compliance and disease education [Citation16].

The objective of this systematic review is to present a collective summary of different pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches for the management of RA based on comprehensive methodology as well as undertake a comparative evidence-based approach for different therapeutic and non-therapeutic modalities in order to provide a solution for the best therapeutic management for obtaining the best clinical outcome, increasing the quality of life of patients and minimizing potential side effects

Methods

In the present review, the following sources were included: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled non-randomized clinical trials (CCTs), retrospective and prospective comparative cohort studies, case control or nested case-control studies, reviews and systematic reviews. On the other hand, case reports and case series were excluded from the study sample.

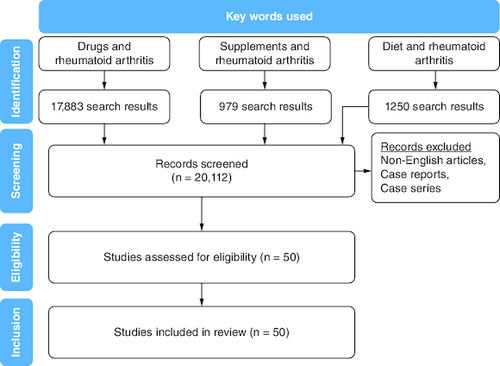

A search strategy was constructed using medical subject headings (MeSH). The MeSH terms of supplements, nutrition, therapy, drugs, management, genetics and rheumatoid arthritis were used to systemically search PubMed and MEDLINE databases. Only studies in the English language with a study population of 18 years and older were included. All relevant publications up to 2022 were included. No limits regarding study design or date were set for the search. Duplicate studies were removed from our study pool (). All included studies were scanned against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our inclusion criteria () primarily focused on published literature that assessed the effect of supplements, nutrition, drugs and genetic factors on RA management.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for search strategy.

The studies underwent review by two independent authors. In case there was a lack of agreement, a third author was sought for consultation, and the discrepancies were resolved through a collaborative discussion to achieve consensus.

All studies included underwent comprehensive data extraction. The extracted data encompassed various aspects, such as evaluation method, study duration, population included, interventions and outcomes related to the effect on rheumatoid arthritis risk and health-related quality of life.

Results & discussion

Different treatment modalities of rheumatoid arthritis

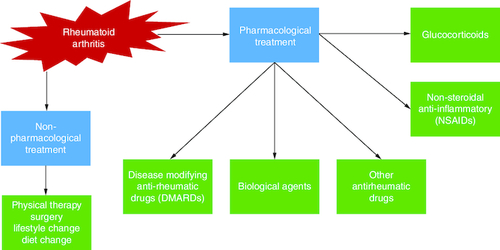

Because RA is an inflammatory disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and glucocorticoids have typically been used as first-line treatments. They work quickly to alleviate RA pain and joint swelling.

Methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine and, more recently, leflunomide are examples of disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs). These slower-acting drugs, unlike NSAIDs, not only relieve symptoms but also decrease clinical and radiographic deterioration. Because their onset period spans from several weeks to months, more rapid-acting drugs, such as NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, are frequently used as ‘bridge’ treatments when starting DMARD therapy ().

Figure 2. A diagram presenting the various treatment modalities for rheumatoid arthritis.

The therapy options for RA are classified into two categories: non-pharmacological treatment and pharmacological treatment. Physical therapy, patient counseling on lifestyle variables, and surgical procedures to remove or replace the affected joint and bone regions are examples of non-pharmacological therapies. Pharmacological therapy includes NSAIDs, which are often used solely for symptomatic therapy or until a RA diagnosis is established since these therapies relieve pain and stiffness but have little effect on disease progression.

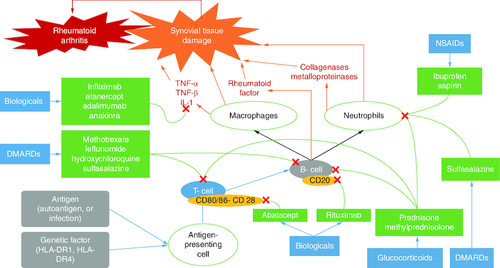

Biological-response modifiers, the most recent class of RA medicines, have been on the market for over 10 years. Examples include infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, anakinra, abatacept and rituximab, which have been developed to target the inflammatory mediators of tissue destruction in RA (). Many additional therapeutic compounds are in various stages of clinical development and may be available in the next few years [Citation2].

Table 2. Mechanisms of different categories of pharmacological therapeutics for the management of rheumatoid arthritis.

Lung exposure to noxious substances, infectious agents including Porphyromonas gingivalis and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), gut microbiota, and dietary variables may cause ACPA citrullination and maturation. Citrullination is mediated by the calcium-dependent enzyme peptidyl-arginine-deiminase (PAD), which results in a post-translational alteration of a positively charged arginine to a polar but neutral citrulline [Citation10].

PAD can be released by granulocytes and macrophages in RA (). ACPA is caused by an aberrant antibody response to a variety of citrullinated proteins found throughout the body, including fibrin, fibronectin, EBNA1, type II collagen, and histones. Many citrullination neoantigens activate MHC class II-dependent T cells, assisting B cells in producing more ACPA [Citation10].

Treatment success and failure are crucial in management of any disease condition. The adverse events of medication and disease conditions play a major role in the success or failure of RA treatment. Because of the danger of acquiring major infections and malignancies, a significant number of RA patients have refractory disease and treatment interruptions. Although interleukins (IL-1, IL-17A), and p38 play important roles in RA pathogenesis, various drugs targeting these variables have not been licensed due to their limited effectiveness and severe side effects ( & ).

Table 3. Summarized data of different referenced studies showing different treatment modalities with treatment failure of rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 4. Summarized data from studies of treatment success of rheumatoid arthritis.

Leading factors for treatment failure of rheumatoid arthritis include the incidence of adverse effects that may lead to treatment discontinuation or noncompliance. Also, lack of treatment efficacy and prolonged disease conditions that were not treated previously can lead to treatment failure.

Treatment success is dependent on the proper selection of the appropriate therapeutic drug, an appropriate dose and dosing intervals. Additionally, compliance with a healthy lifestyle, dietary control and early disease diagnosis and treatment are necessary.

Figure 3. Triggering factors for rheumatoid arthritis.

The mechanism and procedure for triggering action by the different factors can be explained as follows: (A) The interplay of genes and environmental variables at the various trigger sites, such as lung, mouth, and gut, might induce RA. (B) This triggering action is defined by the beginning of self-protein citrullination and the development of autoantibodies against citrullinated peptides.

Data taken from [Citation10].

![Figure 3. Triggering factors for rheumatoid arthritis.The mechanism and procedure for triggering action by the different factors can be explained as follows: (A) The interplay of genes and environmental variables at the various trigger sites, such as lung, mouth, and gut, might induce RA. (B) This triggering action is defined by the beginning of self-protein citrullination and the development of autoantibodies against citrullinated peptides.Data taken from [Citation10].](/cms/asset/1592031e-247b-4129-8e94-11b8b35accdd/ifso_a_2341560_f0003_c.jpg)

The effect of different nutrients, food sources, & therapeutic agents on the clinical outcome of rheumatoid arthritis

Different studies were analyzed for evaluation of different therapeutic approaches on the clinical outcome. A common finding across all studies analyzed was that improvements in RA disease activity were most noticeable for the majority of disease components ().

Table 5. Summarized data for referenced studies investigating the effect of different nutrients, food sources and drugs on RA risk and clinical outcomes.

Dietary sources, which include a gluten-free diet, probiotics either as a supplement or from dietary sources, cranberry juice, ginger, and cinnamon, showed a significant clinical improvement in RA disease condition.

On the other hand, some studies that included vitamin D2, cod liver oil, alpha lipoic acid, and vitamin K1 supplementation reported no contribution of these nutrients to the improvement of RA disease activity or superior clinical outcomes.

The current therapeutic agents used () to treat RA include pain and inflammation management agents such as NSAIDs. The first-line therapy for all newly diagnosed cases of RA includes DMARDs, biological-response modifiers, and targeted agents. Furthermore, glucocorticoids and other antirheumatic therapeutic agents are also used for RA treatment.

Figure 4. Different pathways for the therapeutic agents used in relieving the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

The pathways are different and can be summarized as follows: (A) Control of the immune cells and inflammatory mediators leads to suppression of the inflammatory response and reduction of the activity of the disease (RA). (B) Different molecules contribute to blocking T- and B-cell-mediated responses, like glucocorticoids, DMARDs and biological agents. (C) Biological agents contribute to inflammatory mediator inhibition. (D) NSAIDs inhibit neutrophil aggregation.

Effect of dietary & lifestyle habits on rheumatoid arthritis

RA is associated with an increased risk of acquiring comorbidities, some of which are known to be associated with lifestyle choices such as sedentary behavior, poor or unhealthy diet, smoking, and alcohol consumption. According to several studies, individuals with RA do not engage in health-promoting physical activity. Obesity and diet are strongly related, and obesity is associated with disease severity and a greater number of comorbidities in RA patients [Citation65].

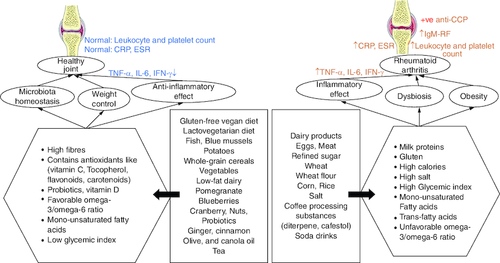

Based on the qualities of individual foods (), dietary habits may constitute both a disease risk and a preventive factor. Specific foods can indeed show pro-inflammatory effects (for example, salt, red meat and high caloric intake) or, in contrast, reduce inflammation (oils, fatty fish, fruit and others). Furthermore, diets represent a major factor influencing microbiota composition, which is involved in disease development. Moreover, changes in lifestyle () can help with RA management.

Figure 5. The indirect correlation between different dietary products and the progression of rheumatoid arthritis.

(A) The effect depends on how food affects inflammatory responses, normal microbiota, and weight control. (B) Usually, diet rich in fiber, vitamins, omega 3 and low-glycemic index foods contribute to protection from RA incidence. (C) Diets with high salt, high calories and a high glycemic index contribute to RA occurrence or incidence.

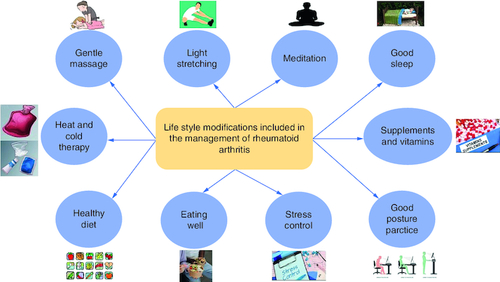

Figure 6. Several lifestyle practices that might be beneficial, when applied by the patients, in controlling and managing rheumatoid arthritis.

(A) The contributing factors for enhancing RA management include dietary habits like healthy food, eating well (eating sufficient quantities of food to provide the required daily caloric need), and supplements. (B) Taking care of physical wellbeing includes good posture practice, regular light exercise, massage, heat, and cold therapy. (C) Emotional, psychological, and mental wellbeing include stress control, meditation, and good and sufficient sleep.

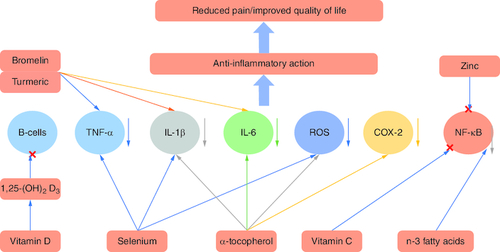

Different molecules and minerals may contribute positively to relieving RA symptoms, preventing disease progression, and enhancing the quality of life of patients. Some supplements suppress TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, such as selenium, α-tocopherol, bromelin and turmeric. Other molecules and minerals like vitamin C, n-3 fatty acids and zinc can contribute to the suppression of the NF-κB pathway. Vitamin D3 has been shown to mitigate B-cell function [Citation66]. Reactive oxygen species are neutralized by antioxidant supplements like vitamin C and α-tocopherol [Citation67]. The blockage of these pathways/inflammatory cytokines results in an anti-inflammatory effect and reduced joint pain ().

Figure 7. Effect of different molecules and minerals on rheumatoid arthritis.

(A) Nutrients affect cells and mediators of the immune-inflammatory ‘cascade’ leading to RA. (B) Once the mediators or cells are controlled, the inflammatory response will be mitigated, causing improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA.

Exercise (light stretching), gentle massage & posture

The pain and stiffness of RA patients may discourage exercise, leading to a sedentary lifestyle, which can exacerbate RA-related symptoms. Failure of proper joint function might weaken the surrounding muscles. Tendons and soft tissue can become inflamed, which can eventually lead to increased joint instability.

Exercise on a regular basis gets the blood flowing into the muscles and can increase the synovial fluid, which can contribute to prevention or reversal of inflammation and joint stiffness. Massage can enhance blood flow through the muscles surrounding the joints, which can reduce joint swelling and relieve pain.

Stress management, sleep wellness & meditation

Stress management can reduce pain and depression by promoting positive improvements in the areas of self-efficacy, coping strategies and overcoming helplessness regarding the control of RA [Citation68]. According to a clinical trial, sleep disruptions are common in RA patients and may increase symptom severity [Citation69]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis found that yoga may be effective for increased physical function, grip strength and reduced disease activity in RA patients [Citation70].

Heat & cold therapy

For individuals with RA, superficial heat and cold treatments are routinely employed [Citation71]. Both methods provide analgesic relief. Temperature changes can affect blood flow, inflammation and nerve sensation. Heat and cold significantly increase the pain threshold immediately after application. Massage can help RA patients reduce suffering and the need for analgesics.

Diet as a risk & protective factor for rheumatoid arthritis

Based on data that supports the unique qualities of different foods and their potential to increase or decrease inflammation, diet may be both a risk factor and a protective factor. Until now, research on this issue has produced contradictory results. Study designs and sample sizes have varied, which have also affected the interpretations.

Excessive red meat intake and a high total protein supply have been linked to an increased risk of inflammatory polyarthritis. Potential reasons for this link include increased inflammation caused by meat fats and nitrites, in addition to increased synovial involvement caused by an excessive oral iron load [Citation72].

High dietary sodium (salt) consumption, which is typical in Western countries, has been linked to an increased risk of RA [Citation73]. High salt levels may exacerbate the negative effects of other environmental variables, particularly smoking, by promoting SGK-1 expression, which leads to increased Th17 cell differentiation and autoimmune enhancement [Citation74].

Clinical research has found that individuals with inflammatory arthritis consume fewer fruits and less vitamin C than controls, and that olive oil consumers have a lower chance of developing RA [Citation75]. Fruits, vegetables, and olive oil may reduce the incidence of RA by supplying antioxidant elements, such as tocopherols found in olive oil, which serve as free radical scavengers [Citation76].

It was found that drinking sugar-sweetened soda on a daily basis increases the risk of RA. High-fructose-flavored soft drinks may help promote arthritis development in young adults by producing an excessive buildup of glycation products that enhance inflammation [Citation77].

Mikuls et al. observed a higher risk of seropositive rheumatoid in those who drank four or more cups of coffee per day, but people who drank more than three cups of tea per day had a lower risk [Citation78]. Furthermore, Heliövaara et al. reported a positive relationship between coffee intake and rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity [Citation79].

Diallyl sulphide, a garlic aroma component, has been shown to suppress mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in murine macrophage-like cells. It also reduced Porphyromonas gingivalis, lipopolysaccharide-stimulated cytokine expression, and NF-κB activation. Porphyromonas gingivalis is a periodontal infection that contributes to RA. Active components (like diallyl sulfide) in garlic reduced the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes in mice with UV-B-irradiated skin [Citation80].

In human intestinal epithelial cells, 6-Shogaol, a ginger component, inhibited the PI3K/Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways [Citation81]. Research showed that red ginger extract decreased paw edema in a rat adjuvant arthritis model [Citation82]. Clinical trials showed that ginger therapy dramatically reduced the expression of the T-bet gene in rheumatoid arthritis patients. T-bet is a transcription factor for T helper (Th1) cells that promotes their proliferation in autoimmune disorders [Citation83].

It is notable that nutrients, foods, and herbal supplements that contain a considerable quantity of fiber, antioxidants and anti-inflammatory mediators can contribute to the mitigation of RA incidence and/or signs and symptoms. On the other hand, a high-sugar diet or drink contributes to the promotion of inflammatory action and the incidence or exacerbation of RA.

Different diet types to manage RA

Various studies have explored the efficacy of additional therapeutic approaches for RA (), including fasting as a complementary treatment, the Mediterranean diet, the Cretan Mediterranean diet, vegetarian diet as anti-inflammatory diets, and the utilization of diverse specific foodstuffs in conjunction with standard drug therapy [Citation84].

Fasting, along with adherence to the Mediterranean diet and specifically the Cretan Mediterranean diet, as well as the adoption of anti-inflammatory diets, has demonstrated the potential to positively impact the therapeutic approach toward RA. This is evidenced by the notion that diet can serve as a supplementary component to the conventional drug therapy for the management of RA. Moreover, it has been documented that the implementation of anti-inflammatory diets led to a notable decrease in pain compared with regular diets [Citation85].

Table 6. Types of diets for management of RA and their impact on disease symptoms.

Genetic effects on rheumatoid arthritis treatment

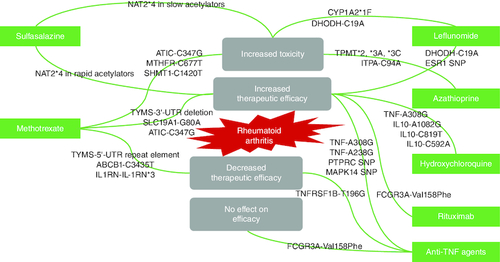

Genetic screening can be introduced in pharmaceutical care services to improve clinical outcomes and enhance the quality of life of RA patients. Certain polymorphic genes may affect, positively or negatively, the therapeutic response or metabolic fate of certain therapeutic molecules ().

The inclusion of pharmaceutical care services in the treatment regimen of RA patients can improve the diagnosis and prevention of drug-related issues. Furthermore, it demonstrated a substantial increase in patient adherence and sense of wellbeing [Citation86].

Regarding traditional DMARDs, several SNPs in genes encoding proteins involved in the nucleotide synthesis, drug transport, folate pathway, and cytokine production may be linked to altered efficacy or toxicity of methotrexate (MTX) [Citation87]. The C3435T SNP in the ABCB1 gene, which codes for the MDR1 efflux pump, is involved in drug transport and increases MTX efflux [Citation88]. ATIC and TYMS are two genes involved in nucleotide synthesis that have been linked to MTX activity. Mutations in these genes alter mRNA stability and enzyme activity, resulting in increased efficacy but high toxicity [Citation89]. Furthermore, an SNP in the IL1RN gene has been linked to reduced MTX effectiveness [Citation90].

From the previous data, it is clear that most of the DMARDs and biological agents are positively affected, regarding their clinical efficacy and toxicity, by different genetic polymorphisms. This underlines the importance of applying genetic screening in healthcare settings in order to provide patients with the most suitable therapeutic choice with minimal side effects and maximum clinical efficacy.

Figure 8. Diagram showing the effect of different genetic variants on rheumatoid arthritis therapeutic outcomes.

(A) The therapeutic outcome is affected by the existence of different genetic variants. (B) Therapeutic efficacy may increase or decrease, toxicity may occur, or no change in efficacy may be seen.

Active & controlled cases how to manage

Over the last few decades, RA care has evolved dramatically, resulting in improved treatment and quality of life for RA patients.

A study showed that in early active RA, the use of tripe therapy sulfasalazine [SSZ]/methotrexate [MTX]/hydroxychloroquine [HCQ] provided highly effective control of disease activity [Citation91]. Furthermore, a clinical study on recently detected RA indicated that the initial combination therapy, including MTX, SSZ and prednisone, or MTX and infliximab, resulted in quicker clinical improvement and slower development of joint damage than the initial monotherapy [Citation92].

Many individuals with controlled RA can retain therapeutic remission. Current therapeutic advice is that glucocorticoids should be discontinued first, followed by a reduction and discontinuation of biologics, and finally, in cases of sustained remission, conventional DMARDs such as methotrexate should be reduced and possibly discontinued. Low disease activity at onset, negative serological testing and a short disease duration after commencing DMARD treatment all contribute to the efficacy of reducing antirheumatic treatments [Citation93].

Study limitations

Gene therapy approaches are not included in the current review.

Conclusion

The balance between ideality and reality in pharmacological therapeutic management, dietary intake and lifestyle behaviors such as physical activity, smoking and alcohol use have an impact on the quality of life of patients with established RA. When addressing the management of RA patients, healthcare professionals may need to provide a tailored regimen/counseling for each patient depending on the patient's health state, disease progression, and current diet and lifestyle to achieve the required improvement in quality of life. Fasting as a complementary treatment along with a Mediterranean diet, vegetarian diet, and vegan diet showed promising results in relieving RA symptoms. Moreover, data revealed that diet with low glycemic index, diet reach in fibers, antioxidants and anti-inflammatory mediators beside therapeutic treatment contribute in enhancing RA treatment outcomes. Supplements such as selenium, α-tocopherol, bromelin, turmeric, vitamin C, n-3 fatty acids, and zinc may contribute positively in reliving RA symptoms and enhancing quality of life in RA management. For future perspective, the integration of genetic and epigenetic data, along with the implementation of machine learning algorithms, holds the potential for truly personalized treatments. With the ongoing advancements in genetic and cell-based therapies, the long-awaited cure for rheumatoid arthritis may finally be attainable. Furthermore, the utilization of continuous treatment adaptations, with a focus on managing comorbidities and addressing lifestyle requirements, could also be made possible. These progressive developments in the field of medicine could significantly enhance the quality of life for individuals suffering from RA.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design: N Ali Sabri; writing – original draft preparation: MA Raslan, SA Raslan, E Mansour Shehata, A Saad Mahmoud, KJ Alzahrani, FM Alzahrani, IF Halawani; writing – review and editing: V Azevedo, K Lundstrom, D Barh; Supervision and project administration: NA Sabri, D Barh.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- Bullock J, Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: a brief overview of the treatment. Med. Princ. Pract. 27(6), 501–507 (2018).

- Gaffo A, Saag KG, Curtis JR. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 63(24), 2451–2465 (2006).

- Kłodziński Ł, Wisłowska M. Comorbidities in rheumatic arthritis. Reumatologia 56(4), 228–233 (2018).

- Dedmon LE. The genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 59(10), 2661–2670 (2020).

- Frisell T, Holmqvist M, Källberg H, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L, Askling J. Familial risks and heritability of rheumatoid arthritis: role of rheumatoid factor/anti-citrullinated protein antibody status, number and type of affected relatives, sex and age. Arthritis Rheum. 65(11), 2773–2782 (2013).

- Chauhan K, Jandu JS, Brent LH, Al-Dhahir MA. Rheumatoid Arthritis. [Updated 2022 Nov 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, FL, USA (2022). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441999/

- Derksen VFAM, Huizinga TWJ, van der Woude D. The role of autoantibodies in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Semin. Immunopathol. 39(4), 437–446 (2017).

- Bullock J, Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: a brief overview of the treatment. Med. Princ. Pract. 27(6), 501–507 (2018).

- Şen V, Ece A, Uluca Ü et al. Evaluation of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in southeastern Turkey: a single center experience. Hippokratia 19(1), 63–68 (2015).

- Guo Q, Wang Y, Xu D, Nossent J, Pavlos NJ, Xu J. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res. 6, 15 (2018).

- Hejazi J, Mohtadinia J, Kolahi S, Bakhtiyari M, Delpisheh A. Nutritional status of Iranian women with rheumatoid arthritis: an assessment of dietary intake and disease activity. Wom. Health 7(5), 599–605 (2011).

- Turesson Wadell A, Bärebring L, Hulander E, Gjertsson I, Lindqvist HM, Winkvist A. Inadequate dietary nutrient intake in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Southwestern Sweden: a cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 9, 915064 (2022).

- Skiba MB, Hopkins LL, Hopkins AL, Billheimer D, Funk JL. Nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplement use in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Nutr. 150(9), 2451–2459 (2020).

- Darlington LG, Stone TW. Antioxidants and fatty acids in the amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis and related disorders. Br. J. Nutr. 85, 251–269 (2001).

- Radu AF, Bungau SG. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Cells 10(11), 2857 (2021).

- Staheli LT. Lower extremity management. In: Arthrogryposis: A Text Atlas. Hall JG, Jaffe KM, Paholke DO ( Eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 55–73 (1998).

- Benjamin O, Goyal A, Lappin SL. Disease - Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARD) [Updated 2023 Jul 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island FL, UK (2023). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507863/

- Elkayam O, Yaron I, Shirazi I, Judovitch R, Caspi D, Yaron M. Active leflunomide metabolite inhibits interleukin 1beta, tumour necrosis factor alpha, nitric oxide, and metalloproteinase-3 production in activated human synovial tissue cultures. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62(5), 440–443 (2003).

- Diaz-Ruiz A, Vergara P, Perez-Severiano F et al. Cyclosporin-A inhibits constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity and neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expressions after spinal cord injury in rats. Neurochem. Res. 30(2), 245–251 (2005).

- Mittal N, Mittal R, Sharma A, Jose V, Wanchu A, Singh S. Treatment failure with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Singapore Med. J. 53(8), 532–536 (2012).

- Fatani AZ, Bugshan NA, AlSayyad HM et al. Causes of the failure of biological therapy at a tertiary center: a cross-sectional retrospective study. Cureus 13(9), e18253 (2021).

- Kim M, Choe YH, Lee SI. Lessons from the success and failure of targeted drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: perspectives for effective basic and translational research. Immune Netw. 22(1), e8 (2022).

- Fleischmann R, Schiff M, van der Heijde D et al. Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthr. Rheumatol. 69, 506–517 (2017).

- He J, Wang Y, Feng M et al. Dietary intake and risk of rheumatoid arthritis – a cross section multicenter study. Clin. Rheum. 35, 2901–2908 (2016).

- Benito-Garcia E, Feskanich D, Hu FB, Mandl LA, Karlson EW. Protein, iron, and meat consumption and risk for rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 9, R16 (2007).

- Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Mellbye O, Haugen M et al. Changes in laboratory variables in rheumatoid arthritis patients during a trial of fasting and one-year vegetarian diet. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 24(2), 85–93 (1995).

- Podas T, Nightingale JM, Oldham R, Roy S, Sheehan NJ, Mayberry JF. Is rheumatoid arthritis a disease that starts in the intestine? A pilot study comparing an elemental diet with oral prednisolone. Postgrad. Med. J. 83(976), 128–131 (2007).

- Alipour B, Homayouni-Rad A, Vaghef-Mehrabany E et al. Effects of Lactobacillus casei supplementation on disease activity and inflammatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 17(5), 519–527 (2014).

- Zamani B, Golkar HR, Farshbaf S et al. Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic supplementation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 19(9), 869–879 (2016).

- Karatay S, Erdem T, Yildirim K et al. The effect of individualized diet challenges consisting of allergenic foods on TNF-α and IL-1β levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 43(11), 1429–1433 (2004).

- Mandel DR, Eichas K, Holmes J. Bacillus coagulans: a viable adjunct therapy for relieving symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis according to a randomized, controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 10(1), 1 (2010).

- Vadell AKE, Bärebring L, Hulander E, Gjertsson I, Lindqvist HM, Winkvist A. Anti-inflammatory diet in rheumatoid arthritis (ADIRA)-a randomized, controlled crossover trial indicating effects on disease activity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 111(6), 1203–1213 (2020).

- Thimóteo NSB, Iryioda TMV, Alfieri DF et al. Cranberry juice decreases disease activity in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 60, 112–117 (2019).

- Lindqvist HM, Gjertsson I, Eneljung T, Winkvist A. Influence of blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) intake on disease activity in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the MIRA randomized cross-over dietary intervention. Nutrients 10(4), 481 (2018).

- Aryaeian N, Shahram F, Mahmoudi M et al. The effect of ginger supplementation on some immunity and inflammation intermediate genes expression in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Gene 698, 179–185 (2019).

- Shishehbor F, Rezaeyan Safar M, Rajaei E, Haghighizadeh MH. Cinnamon consumption improves clinical symptoms and inflammatory markers in women with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 3, 1–6 (2018).

- Hamidi Z, Aryaeian N, Abolghasemi J et al. The effect of saffron supplement on clinical outcomes and metabolic profiles in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 34(7), 1650–1658 (2020).

- Sköldstam L, Hagfors L, Johansson G. An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62(3), 208–214 (2003).

- Mirtaheri E, Gargari BP, Kolahi S et al. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers and matrix metalloproteinase-3 in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 34(4), 310–317 (2015).

- Dawczynski C, Dittrich M, Neumann T et al. Docosahexaenoic acid in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized cross-over study with microalgae vs. sunflower oil. Clin. Nutr. 37(2), 494–504 (2018).

- Buondonno I, Rovera G, Sassi F et al. Vitamin D and immunomodulation in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. PLOS ONE 12(6), e0178463 (2017).

- Hansen KE, Bartels CM, Gangnon RE, Jones AN, Gogineni J. An evaluation of high-dose vitamin D for rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 20(2), 112–114 (2014).

- Rastmanesh R, Abargouei AS, Shadman Z, Ebrahimi AA, Weber CE. A pilot study of potassium supplementation in the treatment of hypokalemic patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J. Pain 9(8), 722–731 (2008).

- Nachvak SM, Alipour B, Mahdavi AM et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on matrix metalloproteinases and DAS-28 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 38(12), 3367–3374 (2019).

- Khojah HM, Ahmed S, Abdel-Rahman MS, Elhakeim EH. Resveratrol as an effective adjuvant therapy in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical study. Clin. Rheumatol. 37(8), 2035–2042 (2018).

- Galarraga B, Ho M, Youssef HM et al. Cod liver oil (n-3 fatty acids) as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug sparing agent in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 47(5), 665–669 (2008).

- Shishavan NG, Gargari BP, Jafarabadi MA, Kolahi S, Haggifar S, Noroozi S. Vitamin K1 supplementation did not alter inflammatory markers and clinical status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 88(5–6), 251–257 (2018).

- Javadi F, Ahmadzadeh A, Eghtesadi S et al. The effect of quercetin on inflammatory factors and clinical symptoms in women with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 36(1), 9–15 (2017).

- Zamani B, Farshbaf S, Golkar HR, Bahmani F, Asemi Z. Synbiotic supplementation and the effects on clinical and metabolic responses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 117(8), 1095–1102 (2017).

- Pineda Mde L, Thompson SF, Summers K, de Leon F, Pope J, Reid G. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot study of probiotics in active rheumatoid arthritis. Med. Sci. Monit. 17(6), CR347–354 (2011).

- Moosavian SP, Paknahad Z, Habibagahi Z. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, evaluating the garlic supplement effects on some serum biomarkers of oxidative stress, and quality of life in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 74(7), e13498 (2020).

- Amalraj A, Varma K, Jacob J et al. A novel highly bioavailable curcumin formulation improves symptoms and diagnostic indicators in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-dose, three-arm, and parallel-group study. J. Med. Food 20(10), 1022–1030 (2017).

- Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy study group. infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-tumor necrosis factor trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy study group. N. Engl. J. Med. 343(22), 1594–1602 (2000).

- St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS et al. Active-controlled study of patients receiving infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of Early Onset Study Group. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 50(11), 3432–3443 (2004).

- Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 48(1), 35–45 (2003).

- Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT et al. Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum. 50(5), 1400–1411 (2004).

- Cohen S, Hurd E, Cush J et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in combination with methotrexate: results of a twenty-four-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 46(3), 614–624 (2002).

- Kremer JM, Westhovens R, Leon M et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N. Engl. J. Med. 349(20), 1907–1915 (2003).

- Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 350(25), 2572–2581 (2004).

- Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 130(6), 478–486 (1999).

- Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Miyasaka N et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 50(6), 1761–1769 (2004).

- Trnavský K, Gatterová J, Lindusková M, Pelisková Z. Combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 52(5), 292–296 (1993).

- Volker D, Fitzgerald P, Major G, Garg M. Efficacy of fish oil concentrate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheum. 27, 2343–2346 (2000).

- Gharib M, Elbaz W, Darweesh E, Sabri NA, Shaweeki MA. Efficacy and Safety of Metformin Use in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized Controlled Study. Front Pharmacol 12, 726490 (2021).

- Malm K, Bremander A, Arvidsson B, Andersson ML, Bergman S, Larsson I. The influence of lifestyle habits on quality of life in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis—A constant balancing between ideality and reality. Int. J. Qualitat. Studies Health Well-being. 11, 1 (2016).

- Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J. Investig. Med. 59(6), 881–886 (2011).

- Liu Z, Ren Z, Zhang J et al. Role of ROS and Nutritional Antioxidants in Human Diseases. Front Physiol. 9, 477 (2018).

- Rhee SH, Parker JC, Smarr KL et al. Stress management in rheumatoid arthritis: what is the underlying mechanism? Arthritis Care Res. 13(6), 435–442 (2000).

- Abbasi M, Yazdi Z, Rezaie N. Sleep disturbances in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Niger J. Med. 22(3), 181–186 (2013).

- Ye X, Chen Z, Shen Z, Chen G, Xu X. Yoga for treating rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 7, 586665 (2020).

- Welch V, Brosseau L, Casimiro L et al. Thermotherapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(2), CD002826 (2002).

- Gioia C, Lucchino B, Tarsitano MG, Iannuccelli C, Di Franco M. Dietary habits and nutrition in rheumatoid arthritis: can diet influence disease development and clinical manifestations? Nutrients 12(5), 1456 (2020).

- Salgado E, Bes-Rastrollo M, de Irala J, Carmona L, Gomez-Reino JJ. High sodium intake is associated with self-reported rheumatoid arthritis: a cross sectional and case control analysis within the SUN cohort. Medicine 94(37), e0924 (2015).

- Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T et al. Induction of pathogenic T H 17 cells by inducible salt-sensing kinase SGK1. Nature 496, 513–517 (2013).

- Serra-Majem L, De la Cruz JN, Ribas L, Tur JA. Olive oil and the Mediterranean diet: beyond the rhetoric. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57, S2–S7 (2003).

- Bustamante MF, Agustín-Perez M, Cedola F et al. Design of an anti-inflammatory diet (ITIS diet) for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 17, 100524 (2020).

- DeChristopher LR, Uribarri J, Tucker KL. Intake of high-fructose corn syrup sweetened soft drinks, fruit drinks and apple juice is associated with prevalent arthritis in US adults, aged 20–30 years. Nutr. Diabetes 6, e199 (2016).

- Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Criswell LA et al. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 83–91 (2002).

- Heliövaara M, Aho K, Knekt P, Impivaara O, Reunanen A, Aromaa A. Coffee consumption, rheumatoid factor, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, 631–635 (2000).

- Letarouilly JG, Sanchez P, Nguyen Y et al. Efficacy of spice supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Nutrients 12(12), 3800 (2020).

- Luettig J, Rosenthal R, Lee I-FM, Krug SM, Schulzke JD. The ginger component 6-shogaol prevents TNF-α-induced barrier loss via inhibition of PI3K/Akt and NF-κB signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 60, 2576–2586 (2016).

- Shimoda H, Shan SJ, Tanaka J et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of red ginger (Zingiber officinale var. Rubra) extract and suppression of nitric oxide production by its constituents. J. Med. Food. 13, 156–162 (2010).

- Sharma JN, Srivastava KC, Gan EK. Suppressive effects of eugenol and ginger oil on arthritic rats. Pharmacology 49, 314–318 (1994).

- Athanassiou P, Athanassiou L, Kostoglou-Athanassiou I. Nutritional Pearls: Diet and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 31, 319–324 (2020).

- Gunes-Bayir A, Mendes B, Dadak A. The integral role of diets including natural products to manage rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review. Curr. Iss. Mol. Biol. 45(7), 5373–5388 (2023).

- Elmenshawy HO, Farouk HM, Sabri NA, Ahmed MA. The impact of pharmaceutical care services on patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled study. Arch. Pharmaceut. Sci. Ain Shams Univ. 6(1), 141–155 (2022).

- Kurkó J, Besenyei T, Laki J, Glant TT, Mikecz K, Szekanecz Z. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis - a comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 45(2), 170–179 (2013).

- Pawlik A, Wrzesniewska J, Fiedorowicz-Fabrycy I, Gawronska-Szklarz B. The MDR1 3435 polymorphism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 42(9), 496–503 (2004).

- Davila L, Ranganathan P. Pharmacogenetics: implications for therapy in rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7(9), 537–550 (2011).

- Tolusso B, Pietrapertosa D, Morelli A et al. IL-1B and IL-1RN gene polymorphisms in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship with protein plasma levels and response to therapy. Pharmacogenomics 7(5), 683–695 (2006).

- Saunders SA, Capell HA, Stirling A et al. Triple therapy in early active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, single-blind, controlled trial comparing step-up and parallel treatment strategies. Arthritis Rheum. 58(5), 1310–1317 (2008).

- Allaart CF, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA. Treatment of recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from the BeSt study. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 80, 25–33 (2007).

- Krüger K, Edelmann E. Therapieabbau bei stabil eingestellter rheumatoider Arthritis. Stand des Wissens [Treatment reduction in well-controlled rheumatoid arthritis. State of knowledge]. Z Rheumatol. 74(5), 414–420 (2015).