Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) are life-limiting and progressive neuromuscular conditions with significant comorbidities, many of which manifest during adolescence. BMD is a milder presentation of the condition and much less prevalent than DMD, making it less represented in the literature, or more severely affected individuals with BMD may be subsumed into the DMD population using clinical cutoffs. Numerous consensus documents have been published on the clinical management of DMD, the most recent of which was released in 2010. The advent of these clinical management consensus papers, particularly respiratory care, has significantly increased the life span for these individuals, and the adolescent years are now a point of transition into adult lives, rather than a period of end of life. This review outlines the literature on DMD and BMD during adolescence, focusing on clinical presentation during adolescence, impact of living with a chronic illness on adolescents, and the effect that adolescents have on their chronic illness. In addition, we describe the role that palliative-care specialists could have in improving outcomes for these individuals. The increasing proportion of individuals with DMD and BMD living into adulthood underscores the need for more research into interventions and intracacies of adolescence that can improve the social aspects of their lives.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) are progressive neuromuscular disorders resulting from mutations in the DMD gene on the X chromosome. The gene controls production of the dystrophin protein; dystrophin provides structure to cells in skeletal and cardiac muscle.Citation1 Short isoforms of the protein are also produced in the brain, and are thought to contribute to neuronal structural stability.Citation1 Current prevalence estimates show 10.2–12.57 in every 100,000 young males worldwide for DMD.Citation2,Citation3 BMD has lower prevalence of 1.53–3.6 in every 100,000 males worldwide.Citation2,Citation3 DMD is typically considered the more severe phenotype and BMD the milder phenotype for childhood onset; however, individuals with DMD and BMD actually present with a wide range of clinical severity within and across the phenotypes.

Historically, individuals with DMD lost ambulation prior to 12 years of age and survived into their late teens. However, surgical, pharmacological, and noninvasive interventions aimed at preserving function have increased survival into the third decade and prolonged ambulation by 2–5 years.Citation4–Citation6 Individuals with BMD have a far more variable presentation, may continue to walk well into their fourth decade or later, and are not typically at higher risk for early mortality, unless they experience early cardiac failure.Citation7 Individuals with DMD and BMD experience proximal–distal skeletal muscle weakness, and death is typically due to either cardiac dysfunction or pulmonary complications as a result respiratory muscle weakness.Citation6 The majority of individuals with DMD and BMD will develop cardiomyopathy, but the onset is variable and studies to date have not determined a consistent marker that can accurately predict onset.Citation8 Prediction of poor pulmonary function is also variable and cannot be accurately predicted, even from sibling function with identical genetic mutations.Citation9 In addition to the decrease in function related to progressive muscle weakness, individuals with DMD and BMD experience a variety of comorbidities and complications from the aging process, treatment side effects, and disease progression.

This article presents a view of current literature across a wide range of topics relevant to adolescent health. While this is not a systematic review, we attempted to apply some rules to the search selection and inclusion of literature reviewed. Briefly, we included articles published within the last 15 years. Article preference was given to review articles that focused on adolescent participants or young adults (13 years and older) and their caregivers or that cited a mean age of at least 13 years when children were included. Searches were performed in PubMed using “Duchenne muscular dystrophy OR Becker muscular dystrophy” AND “adolescence OR adolescent” OR terms appropriate to each topical area of interest and restricting age to adolescents. Manual scans for relevant citations in articles reviewed were also assessed for inclusion. Adolescents with DMD and BMD and their families are faced with a vast array of issues to navigate and manage. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to present current literature on the numerous comorbidities and complications that present during adolescence in individuals with DMD and BMD.

Clinical presentation in adolescence

As more individuals survive into late adolescence and adulthood, it is increasingly important to focus on older individuals with DMD. Prolonged survival increases the need for focus on education, vocation, and adult health care. Adolescents and adults with DMD now have the opportunity to participate in meaningful work, careers, marriage, and independent life. Furthermore, the risk:benefit ratio for significant medical intervention side effects, such as short stature, pubertal delay, and weight gain, needs to be considered, as individuals with DMD live much longer lives. Individuals with BMD will also progressively lose function, but at a more gradual rate, and the fact that they are not at greater risk for mortality than the general population, with the exception of the clinical presentation of cardiomyopathy, is an even stronger argument that proper care, guidance, and self-management for these adolescents are critical for successful transition into adulthood.Citation10

Growth, nutrition, and exercise

The literature on growth delays in individuals with DMD demonstrates preexisting short stature in boys who have not used steroids, which is then exacerbated by steroid use.Citation11,Citation12 There is some evidence that mutations at the distal end of the DMD gene are associated with shorter stature.Citation13 On average, individuals with DMD are 4.3 cm shorter than typically developing children, and by the age of 18 years the majority fall below the fifth percentile on US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth curves.Citation12,Citation14 Weight-for-age DMD growth curves show a preponderance of children above the 90th percentile and below the tenth percentile, which are significantly higher and lower than the CDC growth percentiles, respectively.Citation14 One retrospective review documented more than half the individuals with DMD as overweight at 13 years and over half underweight by 18 years.Citation15 Obesity at 13 years predicted obesity at later ages, whereas normal weight predicted later underweight status, suggesting that maintaining mild obesity at earlier ages may be ideal.Citation15 This weight loss is likely related to progressive muscle weakness leading to dysphagia and mastication dysfunction, with mastication problems occurring even in childhood for individuals with DMD.Citation16–Citation19 Body mass index for age in boys not using steroids is on average 1 kg/m2 above the typical population.Citation14 Comparison of steroid-naïve and steroid-treated individuals with DMD shows significantly increased weight and body mass index and decreased height in steroid-treated boys.Citation11 Once individuals lose ambulation, it becomes difficult to measure height, and weight is only accurate when the wheelchair weight is well documented in the chart.Citation12 There is no information specific to BMD in growth data, despite the dysphagia also experienced by this population.Citation17

Nutrition interventions include supplements for bone health and proactive management of weight through counseling on nutritional status and current activity levels.Citation20 Swallowing dysfunction associated with the progression of skeletal muscle weakness is evident in both DMD and BMD.Citation18,Citation19 Gastrointestinal dysfunction is evident in individuals with DMD, and commonly reported issues include constipation and gastroesophageal reflux disease.Citation21,Citation22 Data on activity levels are scarce; however, stretching and aerobic exercise are clinically recommended, with the caveat of avoiding overexertion and overworking muscle groups.Citation21 Clinically, individuals are often encouraged to participate in low-gravity exercise, such as swimming, stretching, and yoga. A recent review of exercise in DMD human and murine research indicated a need for assessing the effects of exercise on skeletal, cardiac, and pulmonary function simultaneously and to determine whether exercise levels beneficial in mouse models are equally beneficial in humans.Citation23

Side effects of long-term corticosteroid use

The benefits of corticosteroid use are clearly demonstrated in the literature for preservation of function in individuals with DMD; however, there is risk of serious side effects.Citation24 The most common side effects are significant weight gain and behavioral changes, including hyperactivity and inattention, that present during initial treatment and are managed through dosing changes or even discontinued, as the two primary corticosteroids used are not universally available across insurance companies and across countries.Citation25 Some of the other longer-term side effects that are included in care considerations as recommendations for monitoring and intervention are growth retardation, delayed puberty, bone demineralization, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.Citation24

Neurocognitive issues

On average, individuals with DMD perform at 1 SD below the general population on full-scale IQ assessments, while individuals with BMD have average cognitive function.Citation26 Intellectual dysfunction is associated with particular genetic mutations affecting specific dystrophin-protein isoforms, leading to intellectual disability (IQ<70) in about a quarter of the DMD population (20%–27%).Citation27–Citation29 Both DMD and BMD have higher frequencies of learning disabilities and behavioral comorbidities than the general population.Citation26,Citation28 Individuals with DMD frequently have delayed diagnoses of cognitive and behavioral conditions, because focus is generally on medical treatment and intervention. Learning disabilities typically involve executive dysfunction (eg, inattention, disorganization) that is not disruptive in the classroom and compound the likelihood the learning disability will go undiagnosed.Citation30 Almost half the individuals with DMD and 32% of individuals with BMD have a learning disability.Citation26,Citation28 Behavioral conditions, including autism, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and anxiety have been documented as more prevalent than in the general population, with at least 20% of individuals presenting with at least two comorbid cognitive and behavioral conditions.Citation28,Citation29

Disease progression

Pathogenic changes in the cardiac muscle begin at an early age for DMD and BMD, but clinically significant dysfunction is typically seen during the second decade.Citation31 As stated previously, most individuals with DMD and BMD will eventually have dilated cardiomyopathy, but the age of onset and time to death are variable, and to date there have been no clear predictors of an individual’s cardiac prognosis. Studies have shown that the mean age of onset of cardiomyopathy is consistent across both BMD and DMD at ~14.5 years. Other reports indicate that ~85%–90% of DMD will have cardiomyopathy by age 18 years and individuals with BMD will present later with cardiomyopathy in either in the third or fourth decades.Citation7,Citation32 Those with severe cardiomyopathy in the DMD group will typically die from cardiac-related causes, but individuals with BMD are much more likely to qualify for cardiac transplantation.Citation7 Individuals with DMD are unable to qualify for transplant surgery, due to skeletal-muscle impairment, rejection, and low levels of pulmonary function.Citation33 A recent review of the literature indicates individuals with BMD who are eligible for cardiac transplant will tolerate the procedure on par with individuals with other forms of heart failure.Citation33

During adolescence, individuals with DMD will likely lose functional ambulation and become wheelchair-bound. Loss of ambulation and the onset of scoliosis are frequently associated, partly due to the loss of proximal-muscle strength.Citation34 Although the combination of skeletal-muscle weakness and limited mobility contributes to progressive spinal collapse, other factors may also contribute.Citation35 Constant management of wheelchair size, cushion support, and proper seating, especially during adolescence, is essential for preventing progression of scoliosis. When seating accommodation and support are no longer sufficient, surgical intervention may be necessary.Citation34,Citation35 Cheuk et al attempted to perform a Cochrane Database systematic review on scoliosis surgery outcomes, and were unable to provide an evidence-based conclusion due to a lack of randomized controlled trial data.Citation36 The authors found only case series studies in the literature. Individuals with BMD who lost ambulation did so after 16 years of age, and childhood-onset BMD was typically diagnosed as the result of mobility issues related to weakness or myalgia beginning in the second decade.Citation10

The primary cause of pulmonary function decline in DMD is respiratory insufficiency related to respiratory-muscle failure, and is typically diagnosed in adolescence.Citation24 Monitoring pulmonary function is performed through spirometry, which becomes increasingly more challenging as function declines.Citation37 The pattern of decline begins with volume decline, followed by weak cough, hypoventilation requiring partial and then full-time ventilation assistance, and possibly tracheostomy if noninvasive techniques fail or other support and illness factors predict the need.Citation21,Citation38 The monitoring of and intervention in pulmonary dysfunction in DMD since 2004 through illness prevention, flu shots, and device prescription has decreased the proportion of respiratory causes of death in these individuals.Citation38,Citation39

Chronic illness effects on adolescence

Burden of care

The financial costs of health care for individuals with DMD and BMD increase with the age of the individual. As described in the previous section, numerous disease-progression factors and comorbidities begin to present with adolescence. Related treatments, interventions, and equipment are costly, especially when multiple comorbidities are considered. Recent studies demonstrate between a sixfold and tenfold increase in costs over the general population and up to a 16-fold increase between early and late stages, which can be attributed to medical and rehabilitation-technology requirements, increased frequency of visits with specialists, medications, and the need for more skilled caregiving in the home and during hospitalizations.Citation40,Citation41 Most importantly, the indirect costs associated with chronic illness and informal provision of care are the largest burden on individuals and their families, but concentrate in early and late stages of the condition and less so during the intermediate stages during adolescence.Citation40–Citation42 One study on caregivers of adolescents with DMD reported decreased health-related quality of life (QOL) and high rates of anxiety and depression in caregivers, which was predicated on their perception of their child’s overall health levels and whether they considered their child to be happy, which decreased with progression across disease stages.Citation43 The psychological burden on parents is understandably higher for individuals with DMD than BMD, predominantly in feelings of loss and inadequacy of bearing the burden for the family.Citation44

Quality of life

Most studies reporting QOL use scales that take into account physical disability, which significantly skews the overall QOL to be reported lower than those without a disability in scales that consolidate physical and psychosocial domains. The perceived psychosocial QOL for both parents and their affected adolescents with DMD or BMD, excluding physical QOL, does not differ from the general population, with males with DMD reporting even higher QOL than the general population in some studies.Citation42,Citation45–Citation47 While the initial loss of ambulation significantly detracts from QOL, QOL appears to improve again with age, which has been termed the “well-being paradox”.Citation48,Citation49 The same pattern has been found in parents of individuals with DMD, who feel better equipped to manage their child’s condition once ambulation ceases and they concentrate their hopes on the progression of their child as an individual, rather than the progression of the condition.Citation50 Furthermore, equipment typically prescribed due to functional deterioration is seen as a positive improvement, because it reduces other impediments to QOL, such as illness, hospitalizations, or limited access to care locations.Citation51 Parent reports of QOL indicate perceived impaired QOL for their child across all domains. However, it has been shown that parental perceptions report much higher levels of impairment in QOL than direct reports by their children.Citation49,Citation52,Citation53 There have been no QOL studies related to BMD.

Pain

Pain and pain management have received limited research for individuals with DMD and BMD and are infrequently addressed; however, prevalence studies available indicate that pain is pervasive in this population, especially beginning in adolescence. Recent pain studies have reported ~66% of the DMD and BMD population reporting any pain in adolescence, despite low uptake of pain-management services.Citation54–Citation56 Interestingly, activity causes pain in ambulatory individuals, whereas pressure from being sedentary or requiring transfer was the reported cause of pain in nonambulatory individuals, but the frequency of pain symptoms did not differ between the two groups.Citation55 Pain management is discussed in the care considerations of DMD as part of the palliative-care purview, but does not have any specifics associated with pain management, unless it is associated with another comorbid condition, such as bone demineralization or vertebral fractures.Citation21,Citation24

Adolescent effects on chronic illness

Psychosocial adjustment

The literature on depression and anxiety in DMD is mixed. Some data report that individuals with DMD are at no greater risk for adjustment concerns than individuals with other types of chronic illness, who have been reported to improve in their ability to adjust with age.Citation57,Citation58 This finding is likely associated with the well-being paradox previously described: the longer the period from initial diagnosis and initial loss of ambulation, the lower the impact illness has on their psychosocial well-being.Citation48,Citation49,Citation57 Other data have shown an increased prevalence of depression (29%) and anxiety (27%) in adolescents and adults with DMD.Citation28,Citation59 Interviews with adults in advanced stages of DMD indicated that while overall their depression and anxiety was low, they did experience heightened anxiety during critical disease-progression milestones, including full-time wheelchair use and the initiation of mechanical ventilation, which may be one possible explanation for the variable findings on depression and anxiety in the literature.Citation60 Hamdani et al also reported on the importance of maintaining positivity and being happy for interviewed individuals with DMD.Citation61 Lastly, Snow et al reported that some tools used to examine psychosocial adjustment in previous literature may have overreported when individuals were affected by a progressive and chronic illness.Citation29 There have been no studies assessing psychosocial adjustment in adolescents with BMD.

Transition

A review of publications assessing the effects of life-limiting conditions in adolescents and young adults identified a complex transition picture wherein adolescents were dealing with concurrent transitions (eg, transition to adulthood and medical transitions in their health).Citation62 Adolescents with DMD deal with issues with regard to personal developmental transition in conjunction with disease progression and functional deterioration, as well as transition from pediatric to adult care.Citation62 A review of adolescent medical transition best-practice documents showed that while medical transition is aimed at achieving appropriate autonomy and development according to a normal developmental trajectory, for individuals with DMD, transition is more an approximation of adult roles and being “as independent as possible” for individuals with progressive conditions.Citation61 Examples include living an autonomous life, but still living with family to provide the physical assistance needed or working toward employment as an end point in and of itself.Citation61

Several qualitative studies conducted with adolescents and young adults with DMD have demonstrated a critical and unique relationship between affected individuals and their parents or caregivers. As described previously, as individuals with DMD and BMD age, the degree of physical impairment and their dependence increases. Despite this, adolescents and young adults feel independent and autonomous in their lives and their ability to self-advocate and manage their condition in cooperation with their caregivers.Citation63,Citation64 Parents transition from being the primary provider and decision-maker to releasing decision-making and autonomy to their sons, while retaining a position as a knowledgeable consultant in their son’s care.Citation65

Abbott and Carpenter conducted an extensive study on transition and DMD, and demonstrated a difficulty for families with discussing transition, as it deals with the future and with it a reminder of the progressive nature of DMD and BMD.Citation66 Most individuals in the study were essentially socially isolated and without meaningful activity upon completion of education and training, and few families recalled having meetings specific to transition. The authors postulated that medical advances in prolonging life in DMD have not been matched in planning for adulthood, transitioning, and maintaining social lives. While adolescent transition is increasingly being addressed in other medical conditions, it is clear that individuals with DMD are not receiving the same support as individuals with other complex medical conditions. There have been no studies assessing transition in adolescents with BMD.

Transition becomes even more difficult, given the known genetic inheritance of the condition. Mothers often feel guilty for transferring the affected X chromosome and feel responsible for their child’s progressive medical condition. This guilt complicates parental involvement in adolescent-transition processes. Parents may also be unwilling to have discussions regarding long-term outcome, particularly if there is a family history of DMD and loss of older male relatives. However, Fujino et al found that many individuals with DMD were cognizant of their declining muscle strength before they learned they had DMD.Citation60 Individuals with DMD are thus at a deficit during adolescence, because they recognize their declining physical function in a time of independence and autonomy, but lack the knowledge they need to manage their condition. They have little-to-no knowledge about their condition compared with families of children with other types of genetic conditions, and gaining knowledge at this later age can have implications for self-identity development.Citation67

Social challenges

One study reported that young men with DMD did not see their lived experiences as any different from their nondisabled peers. While they acknowledged their physical challenges, they maintained age-appropriate goals, desires, and anticipated trajectories as their peers, specifically “school → college [or vocational education] → work”.Citation68 Most individuals with DMD describe a connection with friends, their parents, and some of their providers, which provides them with comfort.Citation69 The topic of intimate relationships is, however, a significant problem across studies of individuals with DMD. As individuals with DMD live longer, the need for intimate relationships increases, and the lack thereof is more of a concern. Studies with adolescents with DMD have demonstrated discomfort in these individuals when the topic of intimate relationships was raised.Citation68 Other studies have reported the desire for intimate relationships or social interactions with peers that are perceived to be unattainable.Citation69–Citation71 Quantitative studies demonstrate sexual life, employability, and meaningfulness of life as the biggest detractors to QOL, and qualitative self-indicated detractors included intimate relationships, going out, and social relationships.Citation72 There have been no studies assessing social challenges in adolescents with BMD.

Current perspectives on adolescence in DMD and BMD

The role of pediatric palliative care

Palliative care is often used as a synonym for hospice care. The tenets of medical practice in the two services are similar, focusing on communication between patient and provider regarding options for maximizing QOL and the management and relief of discomfort. The crucial difference between hospice care and palliative care is that with the latter, the patient is not necessarily in the end-of-life stages of the disease (ie, death within 6 months). One critical aspect of palliative care involves advanced-care planning and directives; however, research has shown that fewer than 25% of individuals with DMD or their families have any directive documents in place.Citation56,Citation73 Carter et al proposed palliative care as a mechanism for patient empowerment regarding choices in future care through education on disease progression, processes, and intervention options.Citation74 Engaging palliative care during adolescence could ease the transition process by providing families the support systems they need to accept and acknowledge death and allow them instead to focus on affirmation of life through patient education and informed decision-making about future life and medical choices prior to their need.Citation74 In such conditions as DMD, palliative care should be considered complementary to functional preservation interventions.Citation75 Palliative care may be the critical piece of the puzzle to address and manage the issues addressed in this review to ensure the best possible QOL and informed choice, despite the unpredictability of the disease course.Citation75

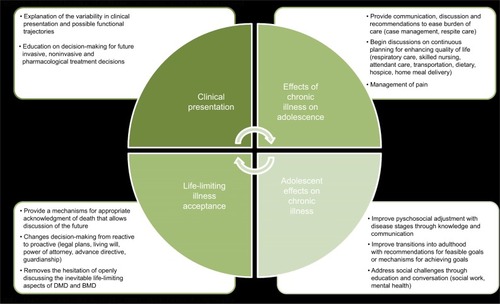

The stated role of pediatric palliative care in life-limiting conditions that present early in life initially involves the management of care and assistance with informed decision-making. Individuals with DMD and BMD initially see a minimum of four medical specialists (neuromuscular, cardiac, respiratory and physical therapy), and this number increases with age as the condition progresses. Often, families are dealing with unpredictable rates of progression and focusing on day-to-day decisions, as opposed to considering decisions holistically and with the future in mind, especially when there are no curative options available.Citation76 The inclusion of palliative-care services into pediatric practice and formal collaboration is infrequent.Citation76 Ironically, the reasons providers state for not bringing end-of-life care into the management of their patient are two central areas in which early palliative-care involvement could have the most impact: uncertain prognosis and inability to acknowledge the condition is incurable.Citation77 Furthermore, physicians who consistently deal with preservation and extension of life may have difficulty discussing topics that are not curative in nature, such as advance directives and other documents dealing with death and the end of life.Citation78 Palliative-care professionals all indicate the need for palliative-care involvement in DMD and BMD from the point of diagnosis onward, as these professionals provide care coordination, education to allow for proactive and anticipatory decision-making about available interventions, and presenting a mechanism for a healthy approach to coming to terms with the possibility of death.Citation75,Citation76,Citation79,Citation80 Clinically, these professionals provide pain and fatigue management, and are equipped to deal with situational mental health needs related to changes in disease trajectory, stages, and end-of-life care. Proactive management of clinical decision-making and the ability to cope with death will provide families with the capacity to manage and execute a social transition plan and expectations for the future, despite the uncertainty of the prognosis.Citation66,Citation76 demonstrates the roles palliative-care professionals can play during adolescence across the topical areas described in this review. More research is needed about incorporating palliative care into the pediatric management of DMD and BMD and its effects on how these individuals manage their transition through adolescence.

Future research needs based on the HEADSS framework

The HEADSS (a mnemonic for home, education/employment, activities, drug use and abuse, sexual behavior, and suicidality and depression) framework is based on a structured interview for adolescents that was developed in 1972.Citation81,Citation82 Many specialists have adopted HEADSS as a framework for conducting their clinical assessment as a form of review of systems for adolescent-medicine visits.Citation83 We summarize the knowledge and gaps in research using the HEADSS domains of home, education and employment, activities, drugs, suicide and depression, and sexuality. summarizes what was reported in the literature reviewed in this article.

Table 1 Summary of research knowledge on adolescent-medicine clinical evaluation areas using the HEADSS framework for DMD and BMD

Home

Research to date has demonstrated good, collaborative relationships between individuals with DMD and BMD and their caregivers.Citation63–Citation65 Caregivers are able to transition decision-making autonomy to their children during adolescence and beyond, and the reported QOL of caregivers for individuals with DMD increases during this time after the event of loss of ambulation of their child. Caregivers report feeling more capable of managing their child’s condition at this stage, and instead focus on rearing their adolescent sons into men.Citation50,Citation84 Caregivers, primarily mothers, continue to report feelings of guilt and inadequacy in caring for a child with DMD and transferring the affected X chromosome to their child.Citation63,Citation69 Transition data demonstrate a delay in discussing the life-limiting nature of the condition with the child, and families hesitate to plan proactively for transition and medical management, avoiding any conversations that may broach subjects related to the variable nature of the condition or death.Citation70,Citation83

Education and employment

Given the proportion of individuals with DMD who will present with an intellectual disability and the fact that all individuals with DMD perform on average at 1 SD below the general population, most individuals with DMD should have an individualized education program to provide them the supports they need to complete secondary school successfully.Citation26–Citation29 All individuals with DMD and BMD are at high risk of learning disabilities involving executive function and other behavioral conditions that can interfere with the learning environment, and should be assessed upon entering school.Citation28–Citation30 Adolescents with DMD and BMD have the same goals as their typically developing peers.Citation68–Citation72 While transition is complex for this group, the fact that families do not recall any meetings specific to transition and actual supports to enact any transition plans are sorely lacking leaves many of these individuals socially isolated and without any meaningful activities to engage in as adults.Citation62,Citation66 Significant efforts need to be made to actualize the transition process, rather than simply making a plan.

Activities

The purpose of addressing activities with adolescents is to gain understanding for their peer group, self-identity, and determine whether social isolation is occurring.Citation81 Engaging in extracurricular activities provides adolescents with structured and supervised time to increase their social relationships with peers who have similar interests. Some of the literature reviewed describes the social relationships of individuals with DMD, but does not address social engagement or participation directly. Several articles report experiences of social isolation for individuals with DMD. More research on early engagement in activities and groups that can continue despite the decline in function during later ages should be undertaken.

Drugs

Hallmarks of adolescence include exploration and risky behavior. The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs 2015 data release reported 15- to 16-year-olds found cigarettes (61%) and alcohol (78%) to be accessible.Citation86 On average, 23% (9%–46%) of responders across the countries reported smoking cigarettes and 47% (14%–72%) report using alcohol by the age of 13 years or younger.Citation86 These topics were not addressed with individuals with DMD or BMD.

Suicide and depression

Studies on depression in DMD have demonstrated reports of depression and QOL on par with the general population.Citation42,Citation45–Citation49 There have been some studies to indicate some increased reporting of depression and anxiety, but these may be attributable to the use of inappropriate scales or directly attributable to a situational change, such as the loss of ambulation when these emotions are natural and understandable.Citation28,Citation29,Citation57–Citation60 There are no data on suicide in DMD or BMD. While mood disorders have been well studied in DMD, there are no data on depression for those with BMD not contending with an early death, but rather a life-long decline in function.

Sexuality

The topic of sexuality has not been addressed relating to sexual activity, risky sexual behavior, or sexual maturity for individuals with DMD. Articles reporting on sexuality in DMD rather described what these individuals imagined sexuality might be like. Intimate relationships appear to be viewed as unattainable for adolescents and young adults with DMD, despite their desire and longing for that type of relationship.Citation68–Citation72 Given the fact that these individuals are living into their fourth decades, extensive research needs to be performed to determine how to alter the mind set that living with a severe disability somehow precludes them from having an intimate relationship and determining a means to increasing their participation in adolescent activities, such as dating. Individuals with BMD who have more severe manifestations of their condition need to be studied regarding their experiences with sexuality as well.

Conclusion

Many topics critical to the adolescent experience have not been addressed in the literature for DMD and BMD. This may be attributable to the relatively recent increase in life span for individuals with DMD changing the adolescent experience from one representing the end of life to one more in keeping with typically developing peers. BMD is infrequently studied, as the prevalence of BMD is far lower than DMD. Literature studying DMD excludes BMD, as the milder and more variable course confounds the DMD data; however, in issues related to adolescent health, the reporting of relevant issues combining DMD and BMD into more of a severity spectrum should be considered. There are risk factors for adolescents that have more of an effect on less severely affected individuals and others that are worse for those with rapid functional decline. Additionally, research addressing the role palliative care can play in improving outcomes during adolescence and beyond is lacking. Regardless, the concept of adolescence and neuromuscular conditions needs to be addressed, given the increasing proportion of adolescents with DMD and BMD who will live well into adulthood and deserve to live as typical a social life as possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank F John Meaney, PhD and Sydney Rice, MD for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- US National Library of MedicineGenetics Home Reference: DMD gene2017 Available from: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/DMDAccessed June 1, 2017

- RomittiPAZhuYPuzhankaraSPrevalence of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies in the United StatesPediatrics2015135351352125687144

- MahJKKorngutLDykemanJDayLPringsheimTJetteNA systematic review and meta-analysis on the epidemiology of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophyNeuromuscul Disord201424648249124780148

- MoxleyRTPandyaSCiafaloniEFoxDJCampbellKChange in natural history of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with long-term corticosteroid treatment: implications for managementJ Child Neurol20102591116112920581335

- EagleMBaudouinSVChandlerCGiddingsDRBullockRBushbyKSurvival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: improvements in life expectancy since 1967 and the impact of home nocturnal ventilationNeuromuscul Disord2002121092692912467747

- PassamanoLTagliaAPalladinoAImprovement of survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: retrospective analysis of 835 patientsActa Myol201231212112523097603

- ConnuckDMSleeperLAColanSDCharacteristics and outcomes of cardiomyopathy in children with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy: a comparative study from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy RegistryAm Heart J20081556998100518513510

- AshwathMLJacobsIBCroweCAAshwathRCSuperDMBahlerRCLeft ventricular dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and genotypeAm J Cardiol2014114228428910.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.03824878125

- BirnkrantDJAraratEMhannaMJCardiac phenotype determines survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophyPediatr Pulmonol2016511707626097149

- FlaniganKMDuchenne and Becker muscular dystrophiesNeurol Clin201432367168825037084

- LambMMWestNAOuyangLCorticosteroid treatment and growth patterns in ambulatory males with Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Pediatr2016173207213.e327039228

- WoodCLStraubVGuglieriMBushbyKCheethamTShort stature and pubertal delay in Duchenne muscular dystrophyArch Dis Child2016101110110626141541

- SarrazinEvon der HagenMScharaUvon AuKKaindlAMGrowth and psychomotor development of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophyEur J Paediatr Neurol2014181384424100172

- WestNAYangMLWeitzenkampDAPatterns of growth in ambulatory males with Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Pediatr2013163617591763.e124103921

- MartigneLSalleronJMayerMNatural evolution of weight status in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a retrospective auditBr J Nutr2011105101486149121272404

- van BruggenHWvan de Engel-HoekLSteenksMHPredictive factors for masticatory performance in Duchenne muscular dystrophyNeuromuscul Disord201424868469224969130

- van den Engel-HoekLde GrootIJSieLTDystrophic changes in masticatory muscles related chewing problems and malocclusions in Duchenne muscular dystrophyNeuromuscul Disord201626635436027132120

- YamadaYKawakamiMWadaAOtsukaTMuraokaKLiuMA comparison of swallowing dysfunction in Becker muscular dystrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophyDisabil Rehabil Epub2017313

- ToussaintMDavidsonZBouvoieVEvenepoelNHaanJSoudonPDysphagia in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: practical recommendations to guide managementDisabil Rehabil201638202052206226728920

- DavidsonZERoddenGMázalaDAPractical nutrition guidelines for individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophyChildersMKRegenerative Medicine for Degenerative Muscle DiseasesHeidelbergSpringer2016225279

- BushbyKFinkelRBirnkrantDJDiagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary careLancet Neurol20109217718919945914

- Lo CascioCMGoetzeOLatshangTDBluemelSFrauenfelderTBlochKEGastrointestinal dysfunction in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophyPLoS One20161110e016377927736891

- HyzewiczJRueggUTTakedaSComparison of experimental protocols of physical exercise for mdx mice and Duchenne muscular dystrophy patientsJ Neuromuscul Dis20152432534227858750

- BushbyKFinkelRBirnkrantDJDiagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial managementLancet Neurol201091779319945913

- BalabanBMatthewsDJClaytonGHCarryTCorticosteroid treatment and functional improvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophyAm J Phys Med Rehabil2005841184385016244521

- YoungHKBartonBAWaisbrenSCognitive and psychological profile of males with Becker muscular dystrophyJ Child Neurol200823215516218056690

- RicottiVMandyWPScotoMNeurodevelopmental, emotional, and behavioural problems in Duchenne muscular dystrophy in relation to underlying dystrophin gene mutationsDev Med Child Neurol2016581778426365034

- BanihaniRSmileSYoonGCognitive and Neurobehavioral profile in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Child Neurol201530111472148225660133

- SnowWMAndersonJEJakobsonLSNeuropsychological and neurobehavioral functioning in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a reviewNeurosci Biobehav Rev201337574375223545331

- AstreaGBattiniRLenziSLearning disabilities in neuromuscular disorders: a springboard for adult lifeActa Myol2016352909528344438

- NigroGComiLIPolitanoLBainRJThe incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophyInt J Cardiol19902632712772312196

- PalladinoAD’AmbrosioPPapaAAManagement of cardiac involvement in muscular dystrophies: paediatric versus adult formsActa Myol201635312813428484313

- PapaAAD’AmbrosioPPetilloRPalladinoAPolitanoLHeart transplantation in patients with dystrophinopathic cardiomyopathy: review of the literature and personal seriesIntractable Rare Dis Res2017629510128580208

- GargSManagement of scoliosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy: a literature reviewJ Pediatr Rehabil Med201691232926966797

- ArcherJEGardnerACRoperHPChikermaneAATatmanAJDuchenne muscular dystrophy: the management of scoliosisJ Spine Surg20162318519427757431

- CheukDWongVWraigeEBaxterPColeASurgery for scoliosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophyCochrane Database Syst Rev201510CD00537526423318

- MayerOHFinkelRSRummeyCCharacterization of pulmonary function in Duchenne muscular dystrophyPediatr Pulmonol201550548749425755201

- BirnkrantDJBushbyKMAminRSThe respiratory management of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a DMD Care Considerations Working Group specialty articlePediatr Pulmonol201045873974820597083

- FinderJDBirnkrantDCarlJRespiratory care of the patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: ATS consensus statementAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170445646515302625

- RyderSLeadleyRMArmstrongNThe burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an evidence reviewOrphanet J Rare Dis20171217928446219

- ThayerSBellCMcDonaldCMThe direct cost of managing a rare disease: assessing medical and pharmacy costs associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the United StatesJ Manag Care Spec Pharm201723663364128530521

- CavazzaMKodraYArmeniPSocial/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in EuropeEur J Health Econ201617Suppl 1192927038625

- LandfeldtELindgrenPBellCFQuantifying the burden of caregiving in Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Neurol2016263590691526964543

- MaglianoLD’AngeloMGVitaGPsychological and practical difficulties among parents and healthy siblings of children with Duchenne vs. Becker muscular dystrophy: an Italian comparative studyActa Myol201433313614325873782

- LandfeldtELindgrenPBellCFHealth-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multinational, cross-sectional studyDev Med Child Neurol201658550851526483095

- TravlosVPatmanSWilsonASimcockGDownsJQuality of life and psychosocial well-being in youth with neuromuscular disorders who are wheelchair users: a systematic reviewArch Phys Med Rehabil201798510041017.e127840132

- VuillerotCHodgkinsonIBisseryASelf-perception of quality of life by adolescents with neuromuscular diseasesJ Adolesc Heal20104617076

- OttoCSteffensenBFHøjbergALPredictors of health-related quality of life in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy from six European countriesJ Neurol2017264470972328175989

- UzarkKKingECripeLHealth-related quality of life in children and adolescents with Duchenne muscular dystrophyPediatrics20121306e1559e156623129083

- SamsonATomiakEDimilloJThe lived experience of hope among parents of a child with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: perceiving the human being beyond the illnessChronic Illn20095210311419474233

- MoranFCSpittleAJDelanyCLifestyle implications of home mechanical insufflation-exsufflation for children with neuromuscular disease and their familiesRespir Care201560796797425516994

- BrayPBundyACRyanMMNorthKNBurnsJHealth status of boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a parent’s perspectiveJ Paediatr Child Health201147855756221392149

- DavisSEHynanLSLimbersCAThe PedsQL in pediatric patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: feasibility, reliability, and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Neuromuscular Module and Generic Core scalesJ Clin Neuromuscul Dis20101139710920215981

- HuntACarterBAbbottJParkerASpintySdeGoedeCPain experience, expression and coping in boys and young men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a pilot study using mixed methodsEur J Paediatr Neurol201620463063827053141

- LagerCKroksmarkAKPain in adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophyEur J Paediatr Neurol201519553754625978940

- AriasRAndrewsJPandyaSPalliative care services in families of males with Duchenne muscular dystrophyMuscle Nerve20114419310121674523

- HendriksenJGPoyskyJTSchransDGSchoutenEGAldenkampAPVlesJSPsychosocial adjustment in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: psychometric properties and clinical utility of a parent-report questionnaireJ Pediatr Psychol2009341697818650207

- ElsenbruchSSchmidJLutzSGeersBScharaUSelf-reported quality of life and depressive symptoms in children, adolescents, and adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cross-sectional survey studyNeuropediatrics201344525726423794445

- LatimerRStreetNConwayKCSecondary conditions among males with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophyJ Child Neurol201732766367028393671

- FujinoHIwataYSaitoTMatsumuraTFujimuraHImuraOThe experiences of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in facing and learning about their clinical conditionsInt J Qual Stud Health Well-being2016113204527712620

- HamdaniYMistryBGibsonBETransitioning to adulthood with a progressive condition: best practice assumptions and individual experiences of young men with Duchenne muscular dystrophyDisabil Rehabil201537131144115125190331

- JohnstonBJindal-SnapeDPringleJLife transitions of adolescents and young adults with life-limiting conditionsInt J Palliat Nurs2016221260861727992275

- SkyrmeSLiving with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: relational autonomy and decision-makingChild Soc2016303220229

- DreyerPSSteffensenBFPedersenBDLiving with severe physical impairment, Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy and home mechanical ventilationInt J Qual Stud Health Well-being2010535388

- YamaguchiMSuzukiMBecoming a back-up carer: parenting sons with Duchenne muscular dystrophy transitioning into adulthoodNeuromuscul Disord2015251859325435264

- AbbottDCarpenterJ“Wasting precious time”: young men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy negotiate the transition to adulthoodDisabil Soc201429811921205

- PlumridgeGMetcalfeACoadJGillPFamily communication about genetic risk information: particular issues for Duchenne muscular dystrophyAm J Med Genet A2010152512251232

- GibsonBEMistryBSmithBBecoming men: gender, disability, and transitioning to adulthoodHealth (London)20141819511423456143

- PehlerSRCraft-RosenbergMLonging: the lived experience of spirituality in adolescents with Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Pediatr Nurs200924648149419931146

- GibsonBEYoungNLUpshurREMcKeeverPMen on the margin: a Bourdieusian examination of living into adulthood with muscular dystrophySoc Sci Med200765350551717482331

- RahbekJWergeBMadsenAMarquardtJSteffensenBFJeppesenJAdult life with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: observations among an emerging and unforeseen patient populationPediatr Rehabil200581172815799132

- PangalilaRFvan den BosGABartelsBQuality of life of adult men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the Netherlands: implications for careJ Rehabil Med201547216116625502505

- AbbottDPrescottHForbesKFraserJMajumdarAMen with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and end of life planningNeuromuscul Disord2017271384427816330

- CarterGTJoyceNCAbreschALSmithAEVandeKeiftGKUsing palliative care in progressive neuromuscular disease to maximize quality of lifePhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am201223490390923137745

- CohnRDBest practice in Duchenne dystrophyNeuromuscul Disord201020429220371092

- RushtonCHIntegrating palliative care in life-limiting pediatric neuromuscular conditions: the case of SMA-type 1 and Duchene muscular dystrophyJ Palliat Care Med201321103

- DaviesBSehringSAPartridgeJCBarriers to palliative care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providersPediatrics2008121228228818245419

- ParkerDMaddocksISternLMThe role of palliative care in advanced muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophyJ Paediatr Child Health199935324525010404443

- WangCHBonnemannCGRutkowskiAConsensus statement on standard of care for congenital muscular dystrophiesJ Child Neurol201025121559158121078917

- HiscockAKuhnIBarclaySAdvance care discussions with young people affected by life-limiting neuromuscular diseases: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesisNeuromuscul Disord201727211511927916344

- CohenEMackenzieRGYatesGLHEADSS, a psychosocial risk assessment instrument: implications for designing effective intervention programs for runaway youthJ Adolesc Health19911275395441772892

- BermanHSTalking HEADS: interviewing adolescentsHMO Pract198711311

- KatzenellenbogenRHEADSS: the “review of systems” for adolescentsAMA J Ethics200573197201

- LandfeldtELindgrenPBellCFHealth-related quality of life in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multinational, cross-sectional studyDev Med Child Neurol201658550851526483095

- MaglianoLPatalanoMSagliocchiA“I have got something positive out of this situation”: psychological benefits of caregiving in relatives of young people with muscular dystrophyJ Neurol2014261118819524202786

- European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other DrugsESPAD Report 2015: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other DrugsLisbonEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction2015