Abstract

The incidence of hypertension in the pediatric population has been increasing secondary to lifestyle changes in children and adolescents. Recent studies have enhanced our understanding of the treatment of pediatric hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have traditionally been the most commonly used class of medication in children with hypertension. This is partly due to the important role of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system pathway in the mediation of pediatric hypertension. Angiotensin receptor blockers provide a reasonable alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. The need for better tolerated antihypertensives had led to development of many new antihypertensives. Valsartan is a relatively novel angiotensin receptor blocker that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of pediatric hypertension. Two recent trials have demonstrated the efficacy of valsartan monotherapy in the pediatric population aged 1–16 years. Once-daily oral preparations of valsartan achieve adequate blood pressure control in the pediatric population. Lack of generic formulations is an important disadvantage. Plasma levels are predictable and clearance is primarily by the liver. Valsartan should be prescribed cautiously for sexually active adolescent females due to concern about angiotensin receptor blocker fetopathy. Otherwise, the drug has infrequent side effects. In summary, valsartan is a new and useful alternative to conventional antihypertensive therapy in pediatric population.

Introduction

Drug therapy in children has traditionally been based on expert opinion, unlike drug therapy in adults. There is a relative lack of data on efficacy as well as safety for most drugs in children due to lack of initiative in enrollment of pediatric populations in many drug trials. Most treatment recommendations in children are extrapolations of data from adult populations. However, following the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997, there has been an exponential increase in data on the safety and efficacy of drug use for pediatric diseases.Citation1 Indeed, these changes have enhanced our understanding of treatment of hypertension in the pediatric population. Many antihypertensive agents have been studied in pediatric populations in recent years and Valsartan is one of these. Valsartan is an angiotensin receptor blocker that was initially approved for treatment of hypertension in adults. It subsequently found uses in several other areas of pharmacotherapeutics in both adult and pediatric populations.Citation2 It is a relatively novel orally formulated angiotensin receptor blocker that has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the pediatric population over the age of six years. It has also been used in Europe for treating pediatric hypertension. Herein, we attempt to review the current role of valsartan in pediatric diseases, with special attention to pediatric hypertension.

Hypertension in children

Guidelines recommend the recording of blood pressure in all otherwise healthy children over the age of three years during routine health visits.Citation3 An average of three blood pressure readings should be used to diagnose hypertension. The diagnosis of hypertension in children is made based on detection of systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ the 95th percentile for gender, age, and height plus 5 mmHg.Citation4 Systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ the 90th percentile or a blood pressure reading more than 120/80 mmHg is deemed as prehypertension. These percentiles are based on data from population-based studies and incorporate the results from the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999–2000 in the US. It is uncertain if the effects of racial differences in blood pressure affect the diagnosis of hypertension in the pediatric population. Interestingly, blood pressure in the more recent NHANES 1999–2000 survey was higher than average blood pressures in similar age groups in 1988–1994.Citation5 This reflects the increasing incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence in developed countries.Citation6 Recent estimates report the incidence of hypertension in US children to be 3.2%, highlighting the magnitude of the problem.Citation7 Furthermore, the presence of elevated blood pressure in childhood and adolescence may predict development of hypertension in adulthood.Citation8

Treatment of primary hypertension in children and adolescents without symptoms or target organ damage is directed towards lifestyle modification and weight loss.Citation4 Pharmacotherapy is indicated for treatment of symptomatic hypertension, secondary hypertension, or hypertension with target organ damage in children. In addition, diabetic children with HTN, and those who do not respond to nonpharmacological measures should be treated with pharmacotherapy.Citation4 Data on the efficacy and safety of these antihypertensives is rather limited in the pediatric population compared with the adult population. Hence, the guidelines do not support the use of one particular class of antihypertensives or agent over others, and leave the decision to the preference of the treating physician.Citation4 However, patients with certain clinical conditions, such as diabetes, may warrant consideration of special classes of antihypertensives, such as angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension. Certain forms of pediatric hypertension are dependent on the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway and may be best treated with drugs acting on this pathway. Finally, the choice of antihypertensives is often directed by the adverse effect profile of a particular class of medication. Currently, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers appear to be the most commonly used classes of antihypertensives in adults due primarily to the relatively infrequent side effects of these agents.Citation9

Current trends in use of antihypertensives in pediatric populations

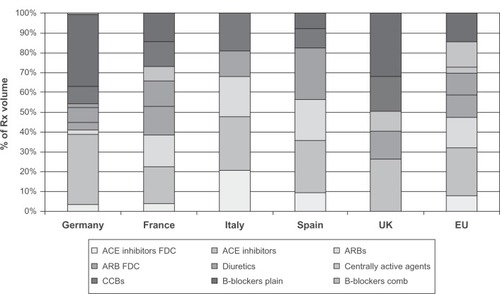

Currently, multiple antihypertensive agents are approved for use in children ().Citation10 A significant number of these medications have been approved since the passing of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act in the US in 1997 and other legislative changes and initiatives.Citation10 Nevertheless, market trends suggest disproportionately more use of certain agents in the pediatric population. Even amongst the commonly used classes of drugs, angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are more commonly prescribed classes compared with diuretics or beta-blockers in the pediatric population.Citation11 Angiotensin receptor blockers as monotherapy or as fixed-dose combinations contributed to 26.3% of pediatric hypertension prescriptions in EuropeCitation11 (). This trend indicates a significant physician and pediatrician preference for these agents independent of compelling indications. A low incidence of side effects with these medications may partly explain this preference.

Figure 1 Use of common antihypertensives in major european countries.

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; FDC, fixed-dose combination; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; Comb, combination; EU, European Union.

Table 1 Pediatric labeling of antihypertensive medications: effect of the FDAMA and successor legislation

Pathophysiology of pediatric hypertension and role of RAAS system

Changes in the RAAS system play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of pediatric hypertension. Renin released from the juxtaglomerular apparatus leads to conversion of angiotensinogen, a decapeptide, to a truncated form, ie, angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is then converted to angiotensin II by the angiotensin-converting enzyme. Angiotensin II binds to angiotensin II receptors to mediate its hypertensive effects. Mechanisms of the hypertensive effects include arteriolar constriction, sympathetic autonomic system activation, aldosterone-mediated sodium and water retention, and antidiuretic hormone-mediated water retention. Most of these antihypertensive effects are mediated through angiotensin II receptor type 1(AT1). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are two major classes of medication that act on the RAAS by causing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin receptor blockade, respectively. Angiotensin receptor blockers may differ in their degree of selectivity in binding to AT1 receptors compared with angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptors. AT2 receptors promote vasodilatation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation, and inhibit cell growth and hypertrophy. AT2 receptor blockade may theoretically negate some of the beneficial effects of AT1 receptor blockade.

RAAS activation might play an important role in obesity-related fluid retention and hypertension, as evidenced by increased levels of renin activity, angiotensin II, and aldosterone in obesity.Citation12 Common causes of secondary hypertension, such as renovascular hypertension and parenchymal renal disease, are mediated through the RAAS.Citation9 Activation of the RAAS also mediates a vicious circle of renal disease and hypertension in both children and adults. In children, intensive blood pressure control and downregulation of the RAAS using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors has been shown to delay progression of chronic kidney disease.Citation13 Young adults and children at risk of hypertension appear to develop changes in renal hemodynamics. Renin and aldosterone levels correlate with the degree of risk of subsequent development of hypertension.Citation14 This implies a major role of antihypertensive agents acting on these pathways in managing hypertension in children. Recent data support the possible use of plasma renin activity to identify patients with difficult to control hypertension and excessive RAAS activity. These patients may respond better to antihypertensives inhibiting the RAAS, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.Citation15

Current status of valsartan

Valsartan is a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor blocker approved by the FDA for treatment of hypertension in children.Citation16 Valsartan was initially approved in Europe for treatment of hypertension in adults, but was subsequently approved in the US for adult prescription and finally, in 2007, was approved for use in children aged 6–16 years. Valsartan has been evaluated either as monotherapy or as a fixed-dose combination with diuretics in more than 60 studies including at least 100,000 patients.Citation17 Being an angiotensin receptor blocker, it confers the benefit of a lower incidence of cough and angioedema compared with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.Citation17 Because of its action of RAAS inhibition, it is one of the antihypertensive agents of choice in patients with heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and/or chronic kidney disease.

Pharmacokinetics

Valsartan is a tetrazole derivative containing acid, giving it a pKa of 4.73 and making it a compound soluble in the neutral pH range. Thus, at physiological pH, the drug exists mainly in the ionized form and is highly soluble. It is less soluble at gastric pH, thus slowing the dissolution of oral valsartan preparations in the stomach.Citation18 Studies in adults reveal that the oral bioavailability of valsartan is in the range of 23%–39%.Citation18 The absorption process consists of an initial rapid absorption phase followed by a second slow absorption phase.Citation18 In children, plasma levels peak at two hours after oral administration and subsequently reduce in a biexponential manner.Citation19 The plasma half-life is about four hours in children under six years of age.Citation19 In children aged 6–12 years, the plasma half-life is about five hours.Citation19 In contrast with losartan, which requires oxidative transformation to the active compound, valsartan is minimally metabolized.Citation20 Overall, less than 20% of the drug is metabolized (in the liver), thus having limited drug-drug interactions.Citation17 About 7.3%–12.6% of the oral dose is excreted unchanged in the urine.Citation18 Thus, most of the drug is excreted unchanged through bile in feces. No significant dosage adjustment is needed in mild to moderate kidney or liver disease. Clearance is not significantly affected by age after correcting for fat free body mass.Citation19,Citation21 The rate of clearance is 0.076–0.098 L/hour/kg in children aged 1–16 years.Citation19 The liver is responsible for most of the plasma clearance, but the clearance is slow at 2 L/hour.Citation18 The drug is minimally bound to adipose tissue in the body.Citation18 Valsartan is more than 90% protein-bound, which is likely to be responsible for its slow clearance from plasma.

Antihypertensive efficacy

Valsartan has been studied in a variety of clinical settings of hypertensive populations. It has been specifically evaluated in pediatric populations aged 1–5 years and 6–16 years.Citation22,Citation23 In adults, valsartan has been compared with more traditional antihypertensives, such as beta-blockers, other angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and has been found to be similarly efficacious.Citation17 Valsartan has been proven effective in treating hypertension as both monotherapy as well as in combination therapy in adults.Citation17 It has been studied in adults in fixed-dose combination with hydrochlorothiazide, with amlodipine, and with aliskiren.Citation17 The valsartan-hydrochlorothiazide combination has been shown to have a faster time to peak action compared with valsartan monotherapy.Citation24 With valsartan monotherapy, the usual time to maximal antihypertensive effect is about two weeks.Citation23 Although valsartan is available as a fixed-dose combination with hydrochlorothiazide and with amlodipine, the efficacy of fixed dose combinations has not been tested in children. However, because the targets to treat for hypertension are more ambiguous in children, use of fixed-dose combinations may not be unreasonable in certain clinical situations.

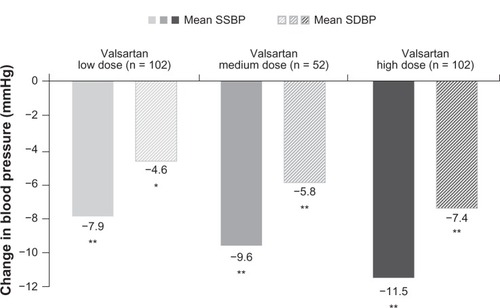

Valsartan as monotherapy has been shown to produce a consistent dose-dependent reduction in both systolic and diastolic blood pressures.Citation23 In the study by Wells et al in children aged 6–16 years, there was an increasing benefit of higher doses of valsartan when separated into low, medium, and high dosesCitation23(). Dose separation was based on body weight, with children weighing less than 35 kg receiving 10 mg, 40 mg, and 80 mg of valsartan as a low, medium, and high dose, respectively. Children weighing over 35 kg received 20 mg, 80 mg, and 160 mg of valsartan as a low, medium and high dose, respectively.Citation23 This represented a dose range of 0.4–2.7 mg/kg. The benefit in reduction of blood pressure was observed irrespective of race (black or nonblack), age (6–11 years or 12–16 years), gender, or weight (<35 kg or ≥35 kg).Citation23 An oral dose of 320 mg, which is the maximum recommended valsartan dose in adults, was not tried in this study. However, the blood pressure reduction was comparable with the blood pressure reduction achieved by losartan in children aged 6–16 years.Citation23,Citation26 In a similar study by Flynn et al, valsartan was found to reduce both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in low-dose, medium-dose, and high-dose groups in children aged 1–5 years.Citation22 The results were consistent across gender, weight, and race, regardless of prior other antihypertensive use. Interestingly, the antihypertensive response in this age group was not found to be dose-related, and was similar to that observed in adults.Citation25 Effects of valsartan 80–160 mg are comparable with those of losartan 50–100 mg.Citation23

Figure 2 Dose-dependent reduction in mean sitting systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure in children aged 6–16 years.

Abbreviations: SSBP, sitting systolic blood pressure; SDBP, sitting diastolic blood pressure.

Other cardiovascular benefits, such as in heart failure, post-myocardial infarction states, and stroke protection in hypertensive adults, have not been tested in pediatric populations. Indeed, the close association of these conditions with atherosclerotic vascular disease makes them rather uncommon entities in the pediatric population. Angiotensin receptor blockers, when added to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in proteinuric children, provide incremental benefit in term of reducing proteinuria, independent of their blood pressure-lowering effect.Citation27 Furthermore, they have been found to reduce left ventricular hypertrophy in a pediatric population with hypertension and renal disease.Citation27

Palatability and dosing

Palatability is an important consideration while prescribing medications to children. Meier et al compared the palatability of various angiotensin receptor blocker tablets in children aged 4–11 years.Citation28 Pulverized tablets of valsartan were reported to be inferior in taste when compared with similar preparations of candesartan and telmisartan. Valsartan can also be dispensed in a suspension form prepared from its tablets.Citation22 There has been no comparison of valsartan suspension with other angiotensin receptor blocker suspensions regarding palatability.

The two landmark studies of valsartan in pediatric populations tested doses of 10–160 mg.Citation22,Citation23 These doses equated to doses of 0.1–4.6 mg/kg (mean doses 0.4–2.7 mg/kg) in children aged 6–16 years.Citation23 A valsartan dose < 0.4 mg/kg is unlikely to be significantly effective.Citation22 The recommended dosage of valsartan for treating hypertension in the pediatric population is 1.3–2.7 mg/kg, with a starting dose of 1.3 mg/kg.Citation16 This amounts to a starting dose of 40 mg in children below 35 kg and 20 mg for children below 15 kg. Doses > 160 mg (4.7 mg/kg) have not been tested in children and may not be recommended. Valsartan has a half-life of about seven hours, which is shorter than the half-life for other newer angiotensin receptor blockers, such as olmesartan and telmisartan. A clinically significant difference in duration of action is noted only when compared with telmisartan. Nevertheless, in adult studies, valsartan prescribed as a once-daily dose has been shown to provide a sustained effect in reducing diastolic as well as systolic blood pressure upon ambulatory blood pressure monitoring both during the daytime and during the night-time.Citation29 Comparison of daytime and night-time dosing has shown no difference in sustainability or degree of blood pressure reduction.Citation30 Thus, valsartan may be taken at any time of the day for treatment of hypertension. Data from heart failure trials in adults support twice-daily dosing.

Adverse effects and tolerance

Angiotensin receptor blockers are the preferred agents for hypertension in terms of side effect profile and tolerance, and are considered even better than angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in this regard. Studies in pediatric populations have revealed that headache might be the most common side effect. In the study by Wells et al, headache was observed in more than 5% of patients, regardless of their blood pressure.Citation23 Another common adverse effect is dose-related dizziness, and this may be caused by excessive hypotension. Another predictable class effect of the angiotensin receptor blockers is hyperkalemia. Serious hyperkalemia has been reported,Citation23 and serum potassium levels should be monitored, especially in children with renal disease and in patients who are concomitantly taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or potassium-sparing diuretics and angiotensin receptor blockers. Hyperkalemia is less common with a fixed-dose valsartan-hydrochlorothiazide combination compared with valsartan alone.Citation22 Cough and angioedema are relatively rare compared with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. In children aged 1–5 years, no significant difference was noted in the overall frequency of adverse effects between valsartan and placebo.Citation22 Adverse effects observed in this study that were deemed possibly valsartan-related included pruritus and rash, hypertriglyceridemia, headache, hepatitis, hyperkalemia, worsening renal function, and thrombocytopenia. Discontinuation of drugs due to adverse effects was rare in both the above trials.Citation22,Citation23

The effects of valsartan on growth and development during infancy and early childhood have been evaluated by Flynn et al.Citation22 Valsartan was found to have no effect on body mass index and height when corrected for age, and did not impact the expected increase in head circumference of children. Expected progress occurred in neurological development parameters such as fine motor skills, gross motor skills, and various parameters of language and social development. Adolescent females prescribed valsartan should be counseled regarding effective contraception, because there is a reasonable risk of fetal developmental defects during pregnancy. In children with clinical suspicion of hypertension secondary to renal artery stenosis, caution should be exercised due to concern about worsening renal function. In summary, apart from certain expected adverse effects that are class effects from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, valsartan has demonstrated reasonable short-term safety in the pediatric population. Nonetheless, these data are based on limited experience with valsartan, and long-term safety data are rather limited.

Conclusion

Valsartan is a novel angiotensin receptor blocker that may have a plausible role in the pediatric population. With the increasing incidence of obesity and changes in lifestyle in developed and developing countries, the incidence of hypertension is bound to increase. Adolescent hypertension is suggested to be the precursor of adult hypertension, and trends in blood pressure during adolescence predict development of adult hypertension.Citation31 Hypertension in children and especially adolescents is expected to increase to epidemic proportions. The need for newer, better tolerated antihypertensive treatment has led to the development of many new antihypertensive agents. Valsartan is one such agent, belonging to a class of angiotensin receptor blockers that is orally formulated and may be a reasonable choice for treating hypertension in children. The efficacy of valsartan has been demonstrated in the pediatric population aged 1–16 years. In addition to treatment of hypertension, valsartan may have a role to play in pediatric heart failure and kidney disease. Based on data in adults, it may be considered as one of the preferred agents in hypertensive children with diabetes or proteinuria. Its efficacy is comparable with that of other angiotensin receptor blockers approved for use in the pediatric population. Once-daily dosing tends to provide a sustained blood pressure-lowering effect over 24 hours. The recommended starting dose is 40 mg, which may be incrementally increased up to 160 mg daily. Common side effects include headache and dizziness, and the latter may be dose-dependent. Limited data suggest that serious adverse effects requiring discontinuation of the drug are infrequent. Palatability is intermediate compared with other angiotensin receptor blockers. It does not appear to affect growth or development in children. Sexually active adolescent females should be counseled regarding effective contraceptive measures while taking valsartan. In summary, valsartan offers another option in the ever-increasing array of antihypertensive therapies in children, and may have a role in treating pediatric hypertension and many other pediatric diseases.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FlynnJTSuccesses and shortcomings of the FDA Modernization ActAm J Hypertens20031688989114553972

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals CorporationDiovan® prescribing informationEast Hanover, NJNovartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation112007

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on Hypertension Control in Children and AdolescentsUpdate on the 1987 task force report on high blood pressure in children and adolescents: A working group report from the National High Blood Pressure Education ProgramPediatrics1996986496588885941

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and AdolescentsThe fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescentsPediatrics2004114Suppl 212215231900

- MunterPHeJCutlerJAWildmanRPWheltonPKTrends in blood pressure among children and adolescentsJAMA20042912107211315126439

- HajjarIKotchenTTrends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000JAMA200329019920612851274

- HansenMLGunnPWKaelberDCUnderdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescentsJAMA200729887487917712071

- BeckettLARosnerBRocheAFSerial changes in blood pressure from adolescence into adulthoodAm J Epidemiol1992135116611771632426

- RobinsonRFNahataMCBatiskyDLPharmacologic treatment of chronic pediatric hypertensionPaediatr Drugs20057274015777109

- KaveyREDanielsSRFlynnJTManagement of high blood pressure in children and adolescentsCardiol Clin20102859760720937444

- BalkrishnanRPhatakHGleimGKarveSAssessment of the use of angiotensin receptor blockers in major European markets among paediatric population for treating essential hypertensionJ Hum Hypertens20092342042519052566

- KotsisVStabouliSPapakatsikaSRizosZParatiGMechanisms of obesity-induced hypertensionHypertens Res2010333893

- WühlETrivelliAPiccaSStrict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in childrenN Engl J Med20093611639165019846849

- van HooftIMGrobbeeDEDerkxFHde LeeuwPWSchalekampMAHofmanARenal hemodynamics and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in normotensive subjects with hypertensive and normotensive parentsN Engl J Med1991324130513112017226

- EganBMBasileJNRehmanSUPlasma renin test-guided drug treatment algorithm for correcting patients with treated but uncontrolled hypertension: A randomized controlled trialAm J Hypertens20092279280119373213

- Diovan® (valsartan) tabletsPrescribing informationEast Hanover, NJNovartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation2008 Available from: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/products/name/diovan.jspAccessed February 16, 2011

- BlackHRBaileyJZappeDSamuelRValsartan: More than a decade of experienceDrugs2009692393241419911855

- FleschGMullerPLloydPAbsolute bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in manEur J Clin Pharmacol1997521151209174680

- BlumerJBatiskyDLWellsTShiVSolar-YohaySSunkaraGPharmacokinetics of valsartan in pediatric and adolescent subjects with hypertensionJ Clin Pharmacol20094923524119179299

- WaldmeierFMuellerPHFleschGPharmacokinetics, disposition and biotransformation of valsartan (CGP 48933) in healthy male volunteers after a single oral dose of 80 mg 14C-radiolabelled preparationXenobiotica19972759719041679

- HabtemariamBSallasWSunkaraGKernSJarugulaVPillaiGPopulation pharmacokinetics of valsartan in pediatricsDrug Metab Pharmacokinet20092414515219430170

- FlynnJTMeyersKENetoJPPediatric Valsartan Study GroupEfficacy and safety of the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan in children with hypertension aged 1 to 5 yearsHypertension20085222222818591457

- WellsTBlumerJMeyersKEThe Valsartan Pediatric Hypertension Study GroupYears with hypertension. Effectiveness and safety of valsartan in children aged 6 to 16J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)20111335736521545397

- JamersonKAZappeDHCollinsLThe time to blood pressure (BP) control by initiating antihypertensive therapy with a higher dose of valsartan (160 mg) or valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide compared to low-dose valsartan (80 mg) in the treatment of hypertension: The VELOCITY studyJ Clin Hypertens200795 Suppl AA166

- PoolJLGlazerRChiangYTGatlinMDose-response efficacy of valsartan, a new angiotensin II receptor blockerJ Hum Hypertens19991327528110333347

- ShahinfarSCanoFSofferBAA double-blind, dose-response study of losartan in hypertensive childrenAm J Hypertens2005182 Pt 118319015752945

- LubranoRSosciaFElliMRenal and cardiovascular effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus angiotensin II receptor antagonist therapy in children with proteinuriaPediatrics2006118e833e83816923922

- MeierCMSimonettiGDGhigliaSPalatability of angiotensin II antagonists among nephropathic childrenBr J Clin Pharmacol20076362863117302913

- DestroMScabrosettiRVanasiaAComparative efficacy of valsartan and olmesartan in mild-to-moderate hypertension: Results of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoringAdv Ther200522324315943220

- HermidaRCCalvoCAyalaDEAdministration time-dependent effects of valsartan on ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive subjectsHypertension20034228329012874091

- TiroshAAfekARudichAProgression of normotensive adolescents to hypertensive adults: A study of 26,980 teenagersHypertension20105620320920547973