Abstract

Binge eating disorder (BED) represents one of the most problematic clinical conditions among youths. Research has shown that the developmental stage of adolescence is a critical stage for the onset of eating disorders (EDs), with a peak prevalence of BED at the age of 16–17 years. Several studies among adults with BED have underlined that it is associated with a broad spectrum of negative consequences, including higher concern about shape and weight, difficulties in social functioning, and emotional-behavioral problems. This review aimed to examine studies focused on the prevalence of BED in the adolescent population, its impact in terms of physical, social, and psychological outcomes, and possible strategies of psychological intervention. The review of international literature was made on paper material and electronic databases ProQuest, PsycArticles, and PsycInfo, and the Scopus index were used to verify the scientific relevance of the papers. Epidemiological research that examined the prevalence of BED in adolescent samples in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition showed a prevalence ranging from 1% to 4%. More recently, only a few studies have investigated the prevalence of BED, in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria, reporting a prevalence of ~1%–5%. Studies that focused on the possible impact that BED may have on physical, psychological, and social functioning showed that adolescents with BED have an increased risk of developing various adverse consequences, including obesity, social problems, substance use, suicidality, and other psychological difficulties, especially in the internalizing area. Despite the evidence, to date, reviews on possible and effective psychological treatment for BED among young population are rare and focused primarily on adolescent females.

Introduction

Binge eating disorder (BED) is an empirically validated eating disorder (ED),Citation1–Citation3 introduced in May 2013 in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).Citation4 BED is characterized by recurrent episodes of unusually large amount of food intake without compensatory behaviors, and it is associated with subjective experience of feeling of loss of control (LOC) and marked distress.Citation5–Citation8 Originally, BED was introduced in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR),Citation9 as a subcategory of Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS). Criteria required binge eating episodes at least twice per week for 6 months, but the new DSM-5 changed this threshold to at least once a week for 3 months.Citation10 Generally, binge eating episodes are preceded by intense feeling of craving,Citation11 and several researchers have suggested that binge eating may serve as a maladaptive strategy for coping with negative mood states.Citation12–Citation16

BED is the most prevalent form of ED and one of the primary chronic illnesses among adolescents.Citation17 Adolescence is a transitional developmental stage characterized by rapid and deep physical, psychological, and neural development changes, and it represents a critical period for the onset of EDs, including BED.Citation18–Citation21 During this period, youths experience fast neurobiological and body modifications, which may be accompanied by increased concern and attention for body size and shape,Citation22–Citation24 as the awareness of societal pressures for thinness and relationships with peers becomes increasingly important, leading to a higher concern about peer acceptance.Citation25–Citation27 For these reasons, although EDs can affect individuals of all ages, adolescence represents a peak lifetime period of increased vulnerability for the onset of EDs.Citation28,Citation29 In particular, an increased prevalence of ED symptoms among youths aged 14–16 years has been evidenced,Citation30 with two peaks of onset of BED, the first immediately after puberty, at a mean age of 14 years,Citation31 and the second in late adolescence (19–24 years), between 18 and 20 years.Citation32

In the general population, international research has reported that 26% of female and 13% of male adolescents have experienced an episode of binge eating at least once in the last 12 monthsCitation33 and that subclinical symptoms of BED can be associated with a higher risk of developing BEDCitation34 and/or other adverse outcomes, including lower self-esteem and higher body dissatisfaction.Citation35

It is noteworthy that binge eating episodes in adolescence could be difficult to differentiate from nonclinical behaviors, as youths could indulge in large food consumption due the developmentally specific growth spurts.Citation36 Consequently, it has been suggested that the criterion of LOC eating is the most salient marker of BED in this developmental phase, especially for early adolescents.Citation37 Furthermore, adolescents may also show less frequent episodes of binge eating than it is necessary to pose a diagnosis of BED according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.Citation18,Citation38,Citation39 For these reasons, it is important for clinicians to consider subthreshold binge eating disorder (SBED) in adolescents.Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation40

It has also been evidenced that female adolescents frequently report less overeating than male adolescents,Citation41 but more severe indicators of loss of control,Citation10,Citation42 and distress during binge eating episodes.Citation10,Citation41 Moreover, several studies among adults with BED have shown that this ED is associated with various adverse consequences, including higher distress and concern about shape and weight,Citation43 social impairment,Citation8,Citation44 and both clinical and subclinical forms of psychological difficulties, especially anxiety and depressive symptoms.Citation7

Based on these theoretical and empirical premises, the aim of this narrative review was to examine the current knowledgeCitation45 of the prevalence of BED in adolescent population, outcomes associated in terms of physical, social, and psychological consequences, and possible psychological strategies of intervention.

Research methods

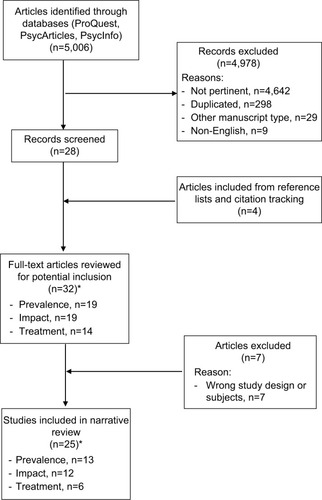

The methodological approach adopted in this paper consists of a narrative review,Citation45,Citation46 an interpretive-qualitative form of research that, when include some features of a systemic methodology,Citation47 can allow synthesizing the findings of literature about a specific theme and improve our knowledge on the topic.Citation48 Specifically, our methodological research () was inspired by the four steps provided by Egger et alCitation49 as follows: 1) formation of a working group, composed of three operators expert in BEDs; one of them has acted as a methodological operator and the other two as clinical operators; 2) formulation of the review questions on the basis of the state of the art of BED in adolescent population (in terms of its prevalence, impact, and possible psychological treatment strategies), as made in the abstract; 3) identification of relevant studies: the review of international literature was performed through an extensive search on paper materials in university libraries and through electronic databases such as ProQuest, PsycArticles, and PsycInfo and indexing papers published from January 2007 to June 2017, together with the use of Scopus index to verify the scientific relevance of papers. First, in order to examine the prevalence rates of binge eating in adolescent population, we were specifically interested in articles that reported the prevalence of both BED and SBED, in accordance with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria, and assessed diagnoses with self-report questionnaires and/or interview instruments. Despite self-report measurements have methodological limitations compared with interview-based assessments, we also included studies using report data to classify diagnoses, because epidemiological research of BED in adolescence is still scarce, and these studies may provide important preliminary data for future studies. This research was performed by using relevant combined keywords such as “binge eating disorder,” “BED,” “subthreshold BED,” “adolescent,” “youth,” “prevalence,” and “epidemiology.”

Table 1 Summary of methodology

Second, to explore the possible impact of BED on adolescents’ health and mental health, we searched for studies presenting physical, social, and psychological outcomes in female and male adolescents with BED and SBED, using the following combined search terms: “adolescence,” “binge eating,” “subthreshold BED,” “outcomes,” “long-term effects,” “impact,” “correlates,” and “consequences.”

Finally, to examine the research focused on possible psychological treatment strategies, we used the keyword search function by entering the following terms: “binge eating disorder,” “adolescence,” “youth,” “psychological treatment,” “psychotherapy,” and “intervention.”

Given that the criterion of LOC eating has been suggested to be a more appropriate indicator of binge eating in adolescence with respect to amount of food consumed,Citation37 we also included treatment studies specifically focused on the reduction of LOC.

We examined the title and screened abstracts of each identified article using these initial search strategies. Then, we also conducted a hand-search of the reference lists of published articles, and papers were inspected for their relevance in the review. On the basis of the evidence of two peaks of onset for BEDCitation31,Citation32 (the first in early adolescence and the second in late adolescence),Citation50 we included in this review only articles in which sample of adolescents was aged between 10 and 24 years. Furthermore, we selected only papers in which sample or subsample of adolescents was diagnosed with BED or SBED, in accordance with either DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria, or studies that examined binge eating symptoms and/or episodes without compensatory behaviors. Other inclusion criteria were that articles in English language and published in peer-reviewed journals. Thesis dissertations were excluded.

The final step is 4) the analysis and presentation of the outcomes; we identified a total of 25 articles, 00 for prevalence,Citation10,Citation18,Citation39,Citation40,Citation51–Citation53,Citation59–Citation62 11 for outcomes,Citation18,Citation39,Citation40,Citation59–Citation61,Citation64–Citation68 and 6 for psychological treatment.Citation79–Citation84 The data extrapolated from these revised studies were collocated in tables and carried out in the form of a narrative review. shows the summary of the methodology used in the review. The flow diagram of the narrative review is shown in .

Results

Prevalence of BED in adolescence

Given that BED has only recently been introduced into the psychiatric nomenclature, epidemiological research is very limited, especially for adolescent populations. We found 13 prevalence studies specifically focused on youths, which have used different types of measurements to assess diagnoses (). Five studiesCitation18,Citation40,Citation51–Citation53 have examined the prevalence of BED in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) and overall reported a rate of prevalence from 1% to 4%. For example, a study by Decaluwé and BraetCitation51 in a population of obese adolescents, using interview measurements, has reported a rate of ~2%. Two other studiesCitation52,Citation53 have examined the rate of BED in general adolescent population, but using self-report questionnaires, reporting a slightly lower prevalence of 1.2%, with a higher rate among female adolescents. These studiesCitation51,Citation52 have also underlined the presence of high percentage of youth who did not meet full-threshold criterion for an ED diagnoses, suggesting limitations of classification systems for epidemiological research among adolescent populations.

Table 2 Prevalence of binge eating disorder in adolescent samples

Finally, we considered two studiesCitation18,Citation40 that, using interview-based assessments, have provided the prevalence rates also for SBED, evidencing a higher prevalence of this form in this phase of development. One studyCitation40 was focused only on adolescent girls, finding a rate of 1% for BED and 4.6% for SBED. The second studyCitation18 had considered both sexes of adolescent population, reporting a prevalence of 1.6% for BED and 2.5% for SBED and evidencing higher rates among girls for SBED also.

Changes to diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 have allowed reducing the prevalence of EDNOS,Citation54 which were ~50% in clinical samplesCitation55,Citation56 and 70% in community samples.Citation57,Citation58 To date, the few studies that have examined the prevalence of BED in adolescent samples, in accordance with the recently proposed DSM-5 criteria, found the prevalence of approximately between 1% and 5%.Citation10,Citation31,Citation32,Citation39,Citation59–Citation62

In particular, we found three studiesCitation39,Citation59,Citation61 that have longitudinally examined the prevalence of BED in adolescent community samples and that suggested an increase of rate over time. For example, Field et alCitation61 found a BED prevalence of 2.5%, which tended to increase during the development, with a peak at 19–22 years of age.

Two other studiesCitation39,Citation59 have confirmed these findings also among male adolescent samples. Interesting, a study by Allen et alCitation59 has reported that BED prevalence increased over time among female adolescents, starting from 0.7% in 14-year-old subjects, reaching 1.4% when they were 17 years, and finally growing up to 4.1% when they were 20 years old. In male adolescents, BED prevalence was estimated to be absent (0%) at 14 years of age and 1.2% at 17 years and was decreased to 0.7% at 20 years, suggesting that adolescent girls have a higher risk of maintaining BED over the course of life. However, another studyCitation37 found that prevalence of BED generally increased over time among both female and male adolescents, peaked at ~3.3% at an age of 22 years for girls and 1.2% at 24 years for boys.

More recently, two cross-sectional studiesCitation31,Citation62 have reported lower rates of prevalence (~1.5%), but among samples of younger adolescents with respects to previous studies in which an increase of prevalence has been evidenced over time.

Finally, we considered three studiesCitation10,Citation32,Citation60 focused also on the prevalence of SBED. Interestingly, the study by Stice et alCitation32 has examined the prevalence of EDs in the same female adolescent samples of their previous study,Citation40 but considering the new DSM-5 criteria, finding an increased prevalence of BED of ~2%. Two other studiesCitation10,Citation60 have replicated similar results but considering also male adolescents. One studyCitation60 was consistent with the previous findings, underlining that female adolescents had a higher prevalence of BED and SBED with respect to their peer male adolescents. In contrast, another studyCitation10 has evidenced a higher rate of BED among female adolescents, but male adolescents reported higher rate of SBED.

Impact of BED on physical, psychological, and social functioning

As seen in the above paragraph, epidemiological research has underlined that BED is common in adolescent population. Research that has focused on the possible consequences of BED on physical, psychological, and social functioning has evidenced that adolescents suffering from BED have an increased risk of developing a variety of adverse outcomes, which may persist into young adulthood.Citation63

Specifically, we reported data from 12 studies showing that BED in adolescence was predictive of a broad spectrum of negative outcomes, including obesity,Citation39,Citation60,Citation61,Citation64 social impairment,Citation18,Citation64,Citation65 other psychological difficulties, especially depressive symptoms,Citation39,Citation59–Citation61,Citation64,Citation67,Citation68 anxiety,Citation60,Citation68 and emotional distress,Citation32,Citation40,Citation68 substance use,Citation39,Citation60,Citation61 and propensity to suicide and deliberate self-harmCitation18,Citation32,Citation60,Citation66 ().

Table 3 Binge eating and physical, social, and psychological outcomes

Regarding the impact of BED on physical health, four prospective cohort studiesCitation39,Citation60,Citation61,Citation64 have underlined that BED was predictive of overweight and obesity, both in girls and boys.Citation39,Citation60,Citation64 In particular, in early adolescents with BED, it has been reported a body mass index (BMI) of ~23 kg/m2,Citation59 is indicative of a healthy weight. However, among this population, BMI tended to increase during later adolescence, with a mean score of 27 kg/m2 among youths with BEDCitation59 and of 26 kg/m2 for SBED,Citation32 representative of a overweight condition (25 < BMI < 29.9 kg/m2), up to a rate of 60% of obese (BMI >30 kg/m2),Citation31 suggesting that binge eating might represent a crucial risk factor for obesity. A study by Field et alCitation61 has shown that 35.1% of female adolescents became overweight and/or obese over the following years, with a significant higher incidence compared with their peers with other EDs. Three other longitudinal studiesCitation39,Citation60,Citation64 have reported similar findings for both female and male adolescents, evidencing that binge eating symptoms are predictive of negative physical consequences (such as obesity) among both sexes.

Furthermore, research has underlined that the impact of BED in adolescence reaches beyond physical adverse outcomes. In particular, we considered three studiesCitation18,Citation64,Citation65 that have suggested that the presence of BED was predictive of a broad spectrum of negative social/interpersonal and outcomes and lower quality of life, in both obese and general adolescent population. A study by Ranzenhofer et alCitation65 focused on an obese adolescent population has shown that binge eating youths reported severe impairments in the domains of health, mobility, and self-esteem compared with their peers without binge eating, even after controlling for body composition. At the same time, two studiesCitation18,Citation64 have replicated similar results also in population-based samples, evidencing that bingeing/overeating symptoms were significantly associated with both social impairment and family burden, in girls and boys. As regards possible different impact of BED and SBED on adolescents’ quality of life, one studyCitation64 has evidenced that 62.6% of adolescents with BED and 34.6% of adolescents with SBED reported impairment in the past year, especially in the domains of social life and household chore, respectively. About 9% of adolescents with BED had severe impairments, particularly in social life, while 2.8% of those with SBED reported severe school or work impairment. Although the research design did not allow causal links, it represented the first population-based study focused on the impact of both threshold and subthreshold of BED in a large population-based samples of female and male adolescents.

With specific regards to the effects on psychological health, we have identified eight studiesCitation18,Citation39,Citation40,Citation59–Citation61,Citation67,Citation68 that have underlined that BED in adolescence is associated with various adverse mental health outcomes, especially anxiety and depressive symptoms. Two studiesCitation61,Citation67 have focused on community sample groups of female adolescents, evidencing a strong association between BED and depressive symptoms. Moreover, in comparison with the other subtype of EDs, BED was the only one illness predictive of depressive symptoms.Citation61 A study by Skinner et alCitation67 has shown that prospective associations between binge eating and depressive symptomatology had similar strength in both directions, suggesting the presence of a bidirectional relationship between these two psychopathological difficulties.

More recently, three studiesCitation39,Citation59,Citation68 have confirmed these associations also for adolescent boys. One of themCitation39 has reported a higher power of prospective associations between BED and depressive symptoms among boys. Moreover, these studies have also evidenced an expanded range of adverse psychological health outcomes predicted by BED, including anxiety and stress symptoms, substance use, and a general low quality of life. However, associations with stress and anxiety symptoms had large effect size.Citation68

Given that prevalence studies have underlined that SBED is very frequent in adolescent population, we considered four studiesCitation18,Citation32,Citation40,Citation60 that have examined the impact of both BED and SBED on psychological well-being. Two longitudinal studiesCitation32,Citation40 on female adolescent community sample have reported that youths with both BED and SBED showed higher mental health difficulties, functional impairment, and emotional distress, than controls did, with no significant differences between the two forms of disease respect to these variables. Consistent with previous studies, a cross-sectional study by Swanson et alCitation18 on a community sample of adolescent girls and boys found significant associations between both BED and SBED with mood disorder, anxiety, alcohol, and drug use, in female and male adolescents (aged 13–18 years). In this study, adolescents with BED showed more difficulties in the area of anxiety, while those with SBED were associated with a higher risk for alcohol and drug use. Another studyCitation60 confirmed similar results even longitudinally, reporting that the main significant associations were between SBED and both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Finally, given that research has underlined clinically significant impairment of BED in adolescence, in terms of physical and mental health difficulties, we considered four studiesCitation18,Citation32,Citation60,Citation66 that have also examined its possible impact on suicidality (in terms of suicidal ideation, suicidal thoughts, and suicidal attempts) or self-injury. Two studiesCitation18,Citation32 found significant associations between BED and SBED and suicidality in female and male adolescents, with a higher effect size for BED. Another studyCitation60 has evidenced that SBED, but not BED, was prospectively significantly associated with deliberate self-harm. Finally, a recent study by Forrest et alCitation66 has reported that the majority of adolescents with BED reported that suicidal ideation followed BED onset, suggesting that binge eating might represent an important risk factor for suicidality in adolescent population.

Psychological treatment strategies

Despite the high prevalence of BED in adolescent populations and the severe physical, social, and psychological associated outcomes, systematic studies on possible and effective psychological treatment for BED among young population are scarce.

Several psychological intervention options have been studied for the treatment of BED in adulthood,Citation69 such as 1) cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),Citation70–Citation72 which concentrates on changing dysfunctional patterns of eating-related thinking and behaviors; 2) behavioral weight loss treatment,Citation73 which are specifically focused on physical activity and modifying diet to reduce overweight and obesity; 3) interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT),Citation69,Citation75 a short-term psychotherapy focused on reducing interpersonal difficulties associated with the onset and/or maintenance of BED; and 4) dialectical behavior therapy (DBT),Citation76,Citation77 which is directly focused on emotional dysregulation and difficulties in coping with one’s own emotions, by promoting the capacity to recognizing, tolerating, and regulating their emotions and mood states.Citation78 Notwithstanding research has demonstrated their efficacy in reducing binge eating in the short and long term, to date, very few studies have examined the possible effectiveness of these psychological interventions also in adolescents with BED. In particular, we found only six studiesCitation79–Citation84 that have developmentally adapted these treatments to adolescent girls and in small samples. Two of themCitation79,Citation80 have examined the effectiveness of CBT, twoCitation81,Citation82 are focused on IPT and the other twoCitation83,Citation84 have used DBT (). We found that no study has focused on psychological intervention on male adolescents.

Table 4 Psychological treatment studies for adolescents with BED

With regard to CBT studies, DeBar et alCitation79 have used an adolescent adaptation of CBT in a sample of female adolescents with BED (52%), recurrent binge eating episodes (32%), or bulimia spectrum disorders (16%). Subjects in CBT group were compared with a usual-delayed treatment (TAU-DT) control group (N=13), in which adolescents received CBT 6 months later. All participants were assessed at baseline and at 3- and 6-month follow-up sessions. Female adolescents in CBT group showed significantly higher abstinence of binge eating episodes at 3- and 6-month follow-up than their peers of TAU-DT group, with a robust effect size. At follow-up, totality of participants of CBT was abstinent. Moreover, the intervention also produced significant improvements in other shape-, weight-, and eating-related concerns, although with a smaller effect size. Finally, girls in the CBT group showed a significant lower depressive symptoms at both the follow-up sessions. However, subjects of TAU-DT group, who were additionally followed up at 9 and 13 months, reported similar outcomes. Although this study provided a preliminary evidence of the efficacy of CBT in reducing binge eating symptoms and their secondary outcomes among adolescent population, homogeneity and small size of sample did not permit generalizability of these findings. Another study by Jones et alCitation80 has investigated the use of an Internet-facilitated CBT-self-help intervention along 16 weeks, compared to a 9-month-wait-list control (WLC) group, for weight maintenance and the reduction of binge eating episodes. In particular, the treatment program was composed by an integrated intervention in which behavioral weight loss (BWL) was combined with CBT. This choice was due to the evidence that in adolescence the specific increased focus on body weight, control of eating behaviors, and dietary that characterizes traditional weight loss programsCitation73 could produce the paradoxical effect of increasing the risk and/or severity of ED symptomatology.Citation85 Moreover, despite traditional BWL programs being found to be effective in the treatment of BED in adults,Citation74 they are specifically focused on the objective overeating episodes, neglecting the aspects of loss of control which are particularly central in BED in adolescence.Citation37 Subjects in CBT group showed significantly lower BMI and BMI z scores at follow-up assessment, a greater decrease in both objective and subjective binge episodes at both posttreatment and follow-up assessments, and a significant reduction of weight- and shape-related concerns than control did, supporting the effectiveness of this intervention also in female adolescents with BED.

Regarding IPT that has been suggested to be an important strategy to reduce binge eating and associated interpersonal problems,Citation69 we found only two studiesCitation81,Citation82 that evaluated its effectiveness in adolescents with BED. A pilot study by Tanofsky-Kraff et alCitation81 focused on IPT in a sample of female adolescents who were at-risk for excessive weight gain, with and without LOC eating, and reported a significant reduction in LOC episodes at 6-month follow-up and in BMI over 1 year, compared with girls randomly assigned to a standard-of-care health education (HE) program group. However, as in most pilot studies, the absence of statistical power did not allow generalizable conclusions on the reported effectiveness. Consequently, more recently, the same authorsCitation82 conducted an adequately powered clinical trial to verify the effectiveness of an adapted IPT group of girls compared to an HE control group. Adolescents of both the groups reported significant reduction of dimensions of BMI (expected BMI gain, BMI z score, and BMI percentile), anxiety and depressive symptomatology, and LOC episodes over 1-year follow-up, with no differences between groups. However, girls in IPT group have shown a significant decrease of binge eating episodes at 12-month follow-up.

Finally, we reported two studiesCitation83,Citation84 specifically interested in examining the effectiveness of DBT in reducing binge eating symptoms. One of them, Safer et al’s study,Citation83 was a case report of a 16-year-old girl, who has shown a significant reduction of binge eating episodes after treatment, and abstinence from binging at 3-month follow-up. Despite potential limitations of case–control studies, we considered this study because it provided a preliminary support for the utility of the adolescent modified version of DBT in reducing binge eating episodes. Finally, Mazzeo et alCitation84 examined the effectiveness of DBT in adolescent girls, compared to a BWL treatment control group, reporting a significant reduction in eating-related concern, shape-related concern, restraint, global disordered eating attitudes, and negative effect in both the groups.

Summary

What is the prevalence of BED in adolescence?

BED has only recently been introduced into the psychiatric nomenclature, and consequently, epidemiological research of this ED in adolescence is in the early stages. Prevalence rate for BED was reported in 13 studies, five of themCitation18,Citation40,Citation51–Citation53 using DSM-IV criteria and eight of themCitation10,Citation31,Citation32,Citation39,Citation59–Citation62 using the DSM-5 criteria. Altogether, our review of the literature on the prevalence of BED has shown that this disorder is very common in adolescence phase, with a rate approximately ranging from 1% to 5%. Moreover, one studyCitation18 has also examined the incidence of BED in female adolescent populations, reporting a rate of 343 per 100,000 persons.

Although most studies have been conducted with the samples of teenage girls, nine studiesCitation10,Citation18,Citation31,Citation39,Citation51–Citation53,Citation59,Citation60 have focused on both the sexes, reporting significant sex-related differences. In particular, girls showed a higher risk for BED than boys (1%–4%; 0%–1.2%, respectively).Citation31,Citation39,Citation52,Citation53,Citation57 However, this sex-related difference was less pronounced in other EDs.Citation86 For this reason, BED represents the most common ED among male adolescent population.Citation87 Moreover, longitudinal studies that we reviewed have evidenced that the prevalence of BED tended to increase over time, with a peak at 19–22 years of age for female adolescentsCitation39,Citation61 and at 24 years for male adolescents.Citation39

Interestingly, it has been evidenced that in adolescents, BED frequently manifests in attenuated, subclinical forms.Citation18,Citation38,Citation39 Indeed, studies with subthreshold adolescentsCitation10,Citation18,Citation32,Citation40,Citation60 found a twofold BED prevalence. Moreover, the prevalence in male adolescents was lower than that in female adolescents also with respect to SBED diagnoses, with 0.3%–4.6% in girls and 0%–2.3% in boys.Citation10,Citation18,Citation60

However, the validity of some of the reviewed studies can be questioned, because the prevalence rate and the definition itself of binge eating may differ depending on the assessment measurements used by researchers. In particular, studies that have used self-report assessmentsCitation52,Citation53,Citation59,Citation61 tended to report higher prevalence than interview-based studies.Citation10,Citation18,Citation31,Citation32,Citation39,Citation40,Citation62 This may depend on the fact that interviews may allow clarifying the subjective experience of “lack of control overeating” and objectively measure the “large food consumption,” which represent two key criteria for the clinical diagnosis of BED. Other specific problems are the general tendency of individuals suffering from BED to hide their illness, the limited awareness of the clinical relevance of their disordered eating, and, consequently, the difficulty to seek for professional help.Citation18,Citation88 For these reasons, future studies on large sample of adolescents from the general population are needed.

What are the physical, social, and psychological outcomes of BED in adolescence?

Research in the last decade has documented the clinical significance of BED in terms of adverse physical, social, and psychological health problems commonly associated with this condition. In particular, with regard to physical outcomes, several studies have reported that BED and SBED, in both female and male adolescents, were predictive of high rates of overweight and obesity.Citation39,Citation60,Citation61,Citation64 This finding supports the view of clinical significance of binge eating, given the important consequences on health associated with obesity in adolescent and adult populations. Indeed, international research has evidenced that obesity is associated with an increased risk to develop severe medical conditions, such as type II diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, and a higher risk for morbidity and mortality.Citation89

However, many studies have underlined that the impact of BED leads to an increased risk of developing a variety of adverse social and emotional-behavioral outcomes, in both obese and population-based adolescent samples.Citation18,Citation65 In particular, the cross-sectional and prospective studies that we considered here have evidenced that both BED and SBED significantly affect health-related quality of life, with marked impairment especially in social and family relationships, and are also associated with negative self-esteem.Citation64,Citation65 More specifically, adolescents with BED tended to show more difficulties in social/interpersonal functioning and work/school achievements, while SBED was strongly associated especially with lower quality of general daily living and family burden.Citation18,Citation39,Citation40,Citation59–Citation61,Citation67,Citation68 Although these consequences of binge eating may be similar for both female and male adolescents, female adolescents reported the highest levels of impairment.Citation18,Citation64,Citation65

Moreover, the studies we reviewed have also evidenced a growing interest in examining possible associations of BED with psychiatric comorbidities. These studies have evidenced that BED in adolescence is a strong predictor of a large spectrum of mental health difficulties. Most of them showed prospective associations with internalizing problems, especially depressive (reported by ~45% of subjects with BED), anxiety, and distress symptoms (as displayed by about one third of adolescents with BED),Citation18,Citation59–Citation61,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67 and suggesting a higher impact on male adolescents.Citation39 Substance use also seems to affect one fourth of subjects with BED.Citation18,Citation39,Citation60

Finally, a few studies have also examined the possible impact of BED on suicidality.Citation18,Citation32,Citation60,Citation66 To date, research in this field is scarce, but some studies suggested that adolescents with either BED or SBED, as well as other EDs,Citation90 had a higher risk of suicidal ideation and attempts than non-eating-disordered youths. In particular, suicidal ideation is found in ~30% adolescents with BED and 20% with SBED, and the frequency of suicidal attempts was 15.1% and 5.3%, respectively.Citation18,Citation32,Citation66 The presence of several self-harm behaviors among BED adolescents has also been evidenced.Citation60 Moreover, although BED is found to co-occur with several mental disorders that are known to increase mortality risks,Citation91,Citation92 to our knowledge no study has so far been published to systematically examine the effects of BED on mortality.

What is the effectiveness of existing psychological interventions for BED in the adolescent population?

To date, evidence for effective treatments for adolescents with BED is growing but yet scarce and inconsistent. This may be due to the fact that BED has only recently been included as a diagnostic category in DSM-5, and, consequently, attention of clinicians on specific intervention in this area is at its dawn.

However, as our review has shown, in the last decade, researchers and clinicians have developmentally adapted some of the intervention approaches that proved effective for the treatment of BED in adult samples.Citation67–Citation73 In particular, we have identified some small trials of CBT,Citation79,Citation80 IPT,Citation81,Citation82 and DBTCitation83,Citation84 involving adolescents and young adults with BED.

In accordance with the NICE guidelines,Citation93 CBT is recommended to be the standard treatment for adult subjects suffering from BED, and our review has confirmed its effectiveness in reducing binge eating symptoms and the severity of risk factors also among adolescent population.Citation79 Moreover, it has also been evidenced that Internet-based CBT interventionsCitation80 can provide a valid support, especially in the early phase of the syndrome. Furthermore, online interventions have been shown to have many advantages for their accessibility, due to the reduced cost and time required, and they may also facilitate adolescent help-seeking. Also the few studies that have used adolescent-adapted IPTCitation81,Citation82 and DBTCitation83,Citation84 have reported findings that seem promising in reducing both binge eating problems and co-occurring mental health symptoms. Interestingly, some interventions have also favored weight loss or a weight maintenance. Given that adult population with BED has been evidenced that overweight typically followed the onset of binge BED,Citation94 previous findings underlined that an early identification and intervention on binge eating in adolescence may reduce the risk of excessive weight gain and, thus, help to prevent adult obesity.

Notwithstanding the studies we reviewed have evidenced some positive preliminary results in reducing binge eating episodes and associated psychopathological symptoms, all of them had small sample size and relatively short follow-up intervals, precluding definitive conclusions about their effectiveness and appropriateness, and suggesting the necessity of implementing long-term longitudinal studies to verify the persistence of clinical benefits over time. Furthermore, additional research comparing these different methodological interventions is needed.

Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet been conducted to confirm the effectiveness of psychological treatment in male adolescents with BED.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that epidemiological studies have suggested that only a small percentage of adolescents with BED (specifically, 11.9%) tended to seek clinical help.Citation18 Moreover, the high rate of adolescents who do not meet full-threshold criteria, although they are affected by various severe physical and psychological negative consequences, makes it even harder to identify them, suggesting the importance of implementing primary prevention programs aimed at increasing awareness, reducing stigma, and promoting acceptance of intervention.

Conclusion

International research has underlined that adolescence is characterized by a high risk for the onset of BED, which represents the most common ED subtype among youths, posing severe risks to their physical and mental health. Several studies have evidenced the complex etiopathogenesis of BED, which seems to result from dynamic and reciprocal relationships between different type of variables, including biological (in particular, familial genetic predisposition and epigenetic processes),Citation95,Citation96 psychological (such as personality traits of perfectionism and impulsivity, negative effect or depressive symptoms, weight and eating concerns, and body dissatisfaction),Citation98–Citation100 and environmental risk factors, in terms of parental influences on childhood eating behavior,Citation95 parental psychopathology and psychopathological risk,Citation101 early adverse experiences, and the presence of traumatic experiences in the parents.Citation102 Among individual risk factor, it has also been reported that dietary restraint, a general rigid eating habits and maladaptive weight control behaviors represent significant risk factor for the onset of BED.Citation103 Moreover, many studies have reported the predictive role played by peer influences and perception of a lack of peer support,Citation104,Citation105 as well as by cultural influences (especially social pressure for thinness and the resulting body dissatisfaction)Citation97,Citation106 on the onset of BED. Overall, these findings suggest the importance of implementing longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials to increase our knowledge of long-term outcomes of BED and support the planning of evidence-based prevention programs and treatment strategies targeted on the risk factors for the onset and maintenance of BED. Given the high prevalence of adolescents who reported SBED, early detection is needed in order to prevent the evolution and worsening of eating symptoms. Moreover, although it has been underlined that a high prevalence of BED may also be found in male adolescent population, there is a dearth of studies that have specifically focused on the possible effectiveness of intervention programs in boys with BED. Thus, future studies including both female and male adolescents with BED are needed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Striegel-MooreRHFrankoDLShould binge eating disorder be included in the DSM-V? A critical review of the state of the evidenceAnnu Rev Clin Psychol2008430532418370619

- EddyKTCrosbyRDKeelPKEmpirical identification and validation of eating disorder phenotypes in a multisite clinical sampleJ Nerv Ment Dis20091971414919155809

- GriloCMIvezajVWhiteMAEvaluation of the DSM-5 severity indicator for binge eating disorder in a clinical sampleBehav Res Ther20157111011426114779

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

- HilbertAPikeKMWilfleyDEFairburnCGDohmFAStriegel-MooreRHClarifying boundaries of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity: a latent structure analysisBehav Res Ther201149320221121292241

- SyskoRRobertoCABarnesRDGriloCMAttiaEWalshBTTest–retest reliability of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnostic criteriaPsychiatry Res2012196230230822401974

- KesslerRCBerglundPAChiuWTThe prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health SurveysBiol Psychiatry201373990491423290497

- KesslerRCShahlyVHudsonJIA comparative analysis of role attainment and impairment in binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: results from the WHO World Mental Health SurveysEpidemiol Psychiatr Sci2014231274124054053

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000

- Lee-WinnAEReinblattSPMojtabaiRMendelsonTGender and racial/ethnic differences in binge eating symptoms in a nationally representative sample of adolescents in the United StatesEat Behav201622273327085166

- SchagKSchönleberJTeufelMZipfelSGielKEFood-related impulsivity in obesity and Binge Eating Disorder – a systematic reviewObes Rev201314647749523331770

- BarryDTGriloCMMashebRMGender differences in patients with binge eating disorderInt J Eat Disord2002311637011835299

- MashebRMGriloCMEmotional overeating and its associations with eating disorder psychopathology among overweight patients with binge eating disorderInt J Eat Disord200639214114616231349

- SteinRIKenardyJWisemanCVDounchisJZArnowBAWilfleyDEWhat’s driving the binge in binge eating disorder? A prospective examination of precursors and consequencesInt J Eat Disord200740319520317103418

- GonzalezAKohnMClarkeSEating disorders in adolescentsAust Fam Physician200736861417676184

- ÁghTKovácsGPawaskarMSupinaDInotaiAVokóZEpidemiology, health-related quality of life and economic burden of binge eating disorder: a systematic literature reviewEat Weight Disord201520111225571885

- NichollsDBarrettEEating disorders in children and adolescentsBJPsych Adv2015213206216

- SwansonSACrowSJLe GrangeDSwendsenJMerikangasKRPrevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplementArch Gen Psychiatry201168771472321383252

- PacielloMFidaRTramontanoCColeECernigliaLMoral dilemma in adolescence: the role of values, prosocial moral reasoning and moral disengagement in helping decision makingEur J Dev Psychol2013102190205

- AndersonNKNicolayOFEating disorders in children and adolescentsSemin Orthod2016223234237

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGTambelliRDo parental traumatic experiences have a role in the psychological functioning of early adolescents with binge eating disorder?Eat Weight Disord201621463564427438789

- PatelPWheatcroftRParkRJSteinAThe children of mothers with eating disordersClin Child Fam Psychol Rev2002511911993543

- WuMLuLHLowesADevelopment of superficial white matter and its structural interplay with cortical gray matter in children and adolescentsHum Brain Mapp20143562806281624038932

- BraySKrongoldMCooperCLebelCSynergistic effects of age on patterns of white and gray matter volume across childhood and adolescenceeNeuro201524315

- GondoliDMCorningAFSalafiaEHBBucchianeriMMFitzsimmonsEEHeterosocial involvement, peer pressure for thinness, and body dissatisfaction among young adolescent girlsBody Image20118214314821354882

- RajagopalanJShejwalBInfluence of sociocultural pressures on body image dissatisfactionPsychol Stud2014594357364

- CernigliaLCiminoSBallarottoGMotor vehicle accidents and adolescents: an empirical study on their emotional and behavioural profiles, defense strategies and parental supportTransp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav2015352836

- Shapiro-WeissGShapiro-WeissJRecent advances in child psychiatry: eating disorders common in high school studentsPsychiatric Guide2001813

- PoppeISimonsAGlazemakersIVan WestDEarly-onset eating disorders: a review of the literatureTijdschr Psychiatr2015571180581426552927

- PretiAde GirolamoGVilagutGThe epidemiology of eating disorders in six European countries: results of the ESEMeD-WMH projectJ Psychiatr Res200943141125113219427647

- SminkFRvan HoekenDOldehinkelAJHoekHWPrevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescentsInt J Eat Disord201447661061924903034

- SticeEMartiCNRohdePPrevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young womenJ Abnorm Psychol2013122244545723148784

- CrollJNeumark-SztainerDStoryMIrelandMPrevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicityJ Adolesc Health200231216617512127387

- Tanofsky-KraffMShomakerLBOlsenCA prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol2011120110821114355

- GoldschmidtABWallMMLothKABucchianeriMMNeumark-SztainerDThe course of binge eating from adolescence to young adulthoodHealth Psychol201433545746023977873

- Herpertz-DahlmannBAdolescent eating disorders: update on definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidityChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am201524117719625455581

- Tanofsky-KraffMMarcusMDYanovskiSZYanovskiJALoss of control eating disorder in children age 12 years and younger: proposed research criteriaEat Behav20089336036518549996

- SwansonSAAloisioKMHortonNJAssessing eating disorder symptoms in adolescence: is there a role for multiple informants?Int J Eat Disord201447547548224436213

- SonnevilleKRHortonNJMicaliNLongitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter?JAMA Pediatr2013167214915523229786

- SticeEMartiCNShawHJaconisMAn 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescentsJ Abnorm Psychol2009118358759719685955

- LewinsohnPMSeeleyJRMoerkKCStriegel-MooreRHGender differences in eating disorder symptoms in young adultsInt J Eat Disord200232442644012386907

- Striegel-MooreRHRosselliFPerrinNGender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptomsInt J Eat Disord200942547147419107833

- WilfleyDEWilsonGTAgrasWSThe clinical significance of binge eating disorderInt J Eat Disord200334196106

- WhismanMADementyevaABaucomDHBulikCMMarital functioning and binge eating disorder in married womenInt J Eat Disord201245338538921560137

- GreenBNJohnsonCDAdamsAWriting narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the tradeJ Chiropr Med2006510117

- PanLPreparing Literature Reviews: Qualitative and Quantitative approaches3rd edGlendale, CAPyrczak Publishing2008

- FerrariRWriting narrative style literature reviewsMedical Writing2015244230235

- GrantMJBoothAA typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologiesHealth Info Libr J2009269110819490148

- EggerMSmithGDAltmanDGSystematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-Analysis in ContextLondon, UKBMJ Publishing Group2001

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent PsychiatryFacts for FamiliesWashington, DCAmerican Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry2011

- DecaluwéVBraetCPrevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatmentInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200327340440912629570

- KjelsåsEBjørnstrømCGötestamKGPrevalence of eating disorders in female and male adolescents 14–15 years)Eat Behav200451132515000950

- AckardDMFulkersonJANeumark-SztainerDPrevalence and utility of DSM-IV eating disorder diagnostic criteria among youthInt J Eat Disord200740540941717506079

- WalshBTReport of the DSM-5 Eating Disorders Work GroupWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development2009

- FairburnCGBeglinSJAssessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire?Int J Eat Disord1994163633707866415

- TurnerHBryant-WaughREating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS): profiles of clients presenting at a community eating disorder serviceEur Eat Disord Rev2004121826

- MachadoPPPGoncalvesSHoekHWDSM-5 reduces the proportion of EDNOS cases: evidence from community samplesInt J Eat Disord201346606522815201

- WadeTDBerginJLTiggemannMBulikCMFairburnCGPrevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohortAust N Z J Psychiatry20064012112816476129

- AllenKLByrneSMOddyWHCrosbyRDDSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 eating disorders in adolescents: prevalence, stability, and psychosocial correlates in a population-based sample of male and female adolescentsJ Abnorm Psychol2013122372024016012

- MicaliNSolmiFHortonNJAdolescent eating disorders predict psychiatric, high-risk behaviors and weight outcomes in young adulthoodJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201554865265926210334

- FieldAESonnevilleKRMicaliNProspective association of common eating disorders and adverse outcomesPediatrics20121302e289e29522802602

- CrowSJSwansonSAle GrangeDFeigEHMerikangasKRSuicidal behavior in adolescents and adults with bulimia nervosaCompr Psychiatry20145571534153925070478

- TablerJUtzRLThe influence of adolescent eating disorders or disordered eating behaviors on socioeconomic achievement in early adulthoodInt J Eat Disord201548662263225808740

- MicaliNPloubidisGDe StavolaBSimonoffETreasureJFrequency and patterns of eating disorder symptoms in early adolescenceJ Adolesc Health201454557458124360247

- RanzenhoferLMColumboKMTanofsky-KraffMBinge eating and weight-related quality of life in obese adolescentsNutrients20124316718022666544

- ForrestLNZuromskiKLDoddDRSmithARSuicidality in adolescents and adults with binge-eating disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication and adolescent supplementInt J Eat Disord2017501404927436659

- SkinnerHHHainesJAustinSBFieldAEA prospective study of overeating, binge eating, and depressive symptoms among adolescent and young adult womenJ Adolesc Health201250547848322525111

- AllenKLByrneSMOddyWHCrosbyRDEarly onset binge eating and purging eating disorders: course and outcome in a population-based study of adolescentsJ Abnorm Child Psychol20134171083109623605960

- WilsonGTWilfleyDEAgrasWSPsychological treatments of binge eating disorderArch Gen Psychiatry20106719410120048227

- GriloCMMashebRMWilsonGTEfficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparisonBiol Psychiatry200557330130915691532

- WilsonGTFairburnCCAgrasWSWalshBTKraemerHCognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: time course and mechanisms of changeJ Consult Clin Psychol200270226727411952185

- AgrasWSFitzsimmons-CraftEEWilfleyDEEvolution of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disordersBehav Res Ther201788263628110674

- GriloCMMashebRMWilsonGTGueorguievaRWhiteMACognitive–behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol201179567568521859185

- MunschSMeyerAHBiedertEEfficacy and predictors of long-term treatment success for cognitive-behavioral treatment and behavioral weight-loss-treatment in overweight individuals with binge eating disorderBehav Res Ther2012501277578523099111

- RiegerEVan BurenDJBishopMAn eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): causal pathways and treatment implicationsClin Psychol Rev201030440041020227151

- SaferDLTelchCFChenEYDialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating and BulimiaNew YorkGuilford Press2009

- KleinASSkinnerJBHawleyKMTargeting binge eating through components of dialectical behavior therapy: preliminary outcomes for individually supported diary card self-monitoring versus group-based DBTPsychotherapy201350454355224295464

- WiserSTelchCFDialectical behavior therapy for binge-eating disorderJ Clin Psychol199955675576810445865

- DeBarLLWilsonGTYarboroughBJCognitive behavioral treatment for recurrent binge eating in adolescent girls: a pilot trialCogn Behav Pract201320214716123645978

- JonesMLuceKHOsborneMIRandomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescentsPediatrics2008121345346218310192

- Tanofsky-KraffMWilfleyDEYoungJFA pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesityInt J Eat Disord201043870170619882739

- Tanofsky-KraffMShomakerLBWilfleyDETargeted prevention of excess weight gain and eating disorders in high-risk adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trialAm J Clin Nutr201410041010101825240070

- SaferDLCouturierJLLockJDialectical behavior therapy modified for adolescent binge eating disorder: a case reportCogn Behav Pract2007142157167

- MazzeoSELydeckerJHarneyMDevelopment and preliminary effectiveness of an innovative treatment for binge eating in racially diverse adolescent girlsEat Behav20162219920527299699

- CooperZFairburnCGA new cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of obesityBehav Res Ther200139549951111341247

- NaglMJacobiCPaulMPrevalence, incidence, and natural course of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among adolescents and young adultsEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201625890391826754944

- SminkFRVan HoekenDHoekHWEpidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality ratesCurr Psychiatry Rep201214440641422644309

- Herpertz-DahlmannBAdolescent eating disorders: update on definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidityChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am201524117719625455581

- ReillyJJMethvenEMcDowellZCHealth consequences of obesityArch Dis Child200388974875212937090

- KostroKLermanJBAttiaEThe current status of suicide and self-injury in eating disorders: a narrative reviewJ Eat Disord2014211926034603

- ChesneyEGoodwinGMFazelSRisks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-reviewWorld Psychiatry201413215316024890068

- CoughlanHTiedtLClarkeMPrevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders, deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation in early adolescence: an Irish population-based studyJ Adolesc20143711924331299

- IGuidelinesCEEating Disorder: Recognition and Treatment, Version 1 Commissioned by theNational Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceLondon, UK; 2016

- MussellMPMitchellJEWellerCLRaymondNCCrowSJCrosbyRDOnset of binge eating, dieting, obesity, and mood disorders among subjects seeking treatment for binge eating disorderInt J Eat Disord19951743954017620480

- CrowSJPetersonCBSwansonSAIncreased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disordersAm J Psychiatry2009166121342134619833789

- CampbellLCMillJUherRSchmidtUEating disorders, gene-environment interactions and epigeneticsNeurosci Biobehav Rev201135378479320888360

- SticeEGauJMRohdePShawHRisk factors that predict future onset of each DSM–5 eating disorder: predictive specificity in high-risk adolescent femalesJ Abnorm Psychol20171261385127709979

- LavenderJMUtzingerLMCaoLReciprocal associations between negative affect, binge eating, and purging in the natural environment in women with bulimia nervosaJ Abnorm Psychol2016125338138626692122

- TambelliRCernigliaLCiminoSAn exploratory study on the influence of psychopathological risk and impulsivity on BMI and perceived quality of life in obese patientsNutrients201795E43128445437

- BallarottoGPorrecaAErriuMDoes alexithymia have a mediating effect between impulsivity and emotional-behavioural functioning in adolescents with binge eating disorder?Clin Neuropsychiatry2017144247256

- TafàMCiminoSBallarottoGBracagliaFBottoneCCernigliaLFemale adolescents with eating disorders, parental psychopathological risk and family functioningJ Child Fam Stud20172612839

- CernigliaCCiminoSBallarottoGTambelliRDo parental traumatic experiences have a role in the psychological functioning of early adolescents with binge eating disorder?Eat Weight Disord201621463564427438789

- HudsonJILalondeJKBerryJMBinge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individualsArch Gen Psychiatry200663331331916520437

- SalvySJDe La HayeKBowkerJCHermansRCInfluence of peers and friends on children’s and adolescents’ eating and activity behaviorsPhysiol Behav2012106336937822480733

- SticeEPresnellKSpanglerDRisk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2-year prospective investigationHealth Psychol200221213113811950103

- TinSPHoSYMakKHWanKLLamTHLifestyle and socioeconomic correlates of breakfast skipping in Hong KongPrev Med2011523–425025321215276