Abstract

Introduction

Compared to adults, adolescents and young adults have a higher incidence of HIV infection, yet lower rates of HIV testing. Few evidence-based interventions effectively diagnose new HIV infections among adolescents while successfully providing linkage to care.

Methods

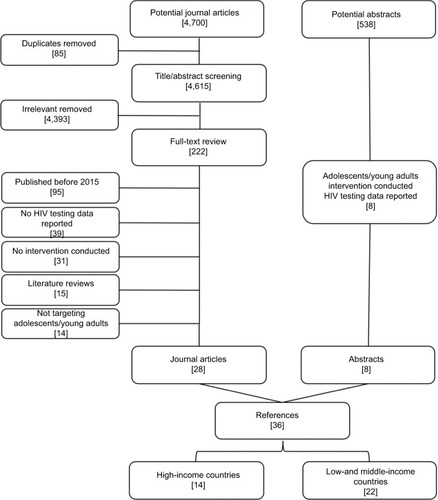

We conducted a systematic review of recent interventions to increase HIV testing among adolescents and young adults using data retrieved from PubMed and Google Scholar, and using abstracts presented at the International AIDS Society conferences and Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections published between January 1, 2015, and April 28, 2018.

Results

We identified 36 interventions (N=14 in high- income countries and N=22 in low- and middle-income countries) that were published in the literature (N=28) or presented at conferences (N=8). Interventions were categorized as behavioral/educational, alternate venue/self-testing, youth-friendly services, technology/mobile health, incentives, or peer-based/community-based interventions. The studies consisted of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective observational studies, and quasi-experimental/pre–post evaluations with variable sample sizes. Study designs, populations, and settings varied. All categories showed some degree of acceptability, yet not all interventions were effective in increasing HIV testing. Effectiveness was seen in more than one RCT involving technology/mobile health (2/3 RCTs) and alternative venue/self-testing (3/3 RCTs) interventions, and only in one RCT each for behavioral interventions, community interventions, and incentives. There were no effective RCTs for adolescent-friendly services. Data were limited on the number of new infections identified and on the methods to increase linkage to care after diagnosis.

Conclusion

Future studies should include combinations of proven methods for engaging adolescents in HIV testing, while ensuring effective methods of linkage to care.

Introduction

Worldwide in 2016, an estimated 2.1 million adolescents aged 10–19 years were living with HIV.Citation1 Globally, one-third of all new HIV infections occurs among adolescents.Citation2 Eighty percent of all adolescent HIV infections worldwide occur in sub-Saharan Africa where females are disproportionately affected compared to males.Citation1,Citation3 In sub-Saharan Africa, less than a third of all adolescents have ever tested for HIV and only 20% of adolescent girls who are living with HIV know their HIV status.Citation1,Citation3 There are limited evidence-based interventions targeting this population that effectively diagnose and link adolescents and young adults to care.

In the US, more than 61,000 adolescents are living with HIV.Citation4 In 2016, of all the new HIV diagnoses among adolescents in the US, 81% were attributed to male-to-male sexual contact.Citation4 Despite the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for one-time HIV testing for all individuals aged 13–64 and annual testing in high-risk groups, testing rates among adolescents and young adults remain low.Citation4,Citation5 Among high school aged men who have sex with men (MSM), only 21% ever had an HIV test.Citation4 Despite numerous interventions to increase HIV testing among high-risk adolescents and young adults, 44% of those living with HIV have not been tested and are unaware of their positive status.Citation4

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS has set the target of 90-90-90 by the year 2020, describing the percentage goals for HIV testing, antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, and viral suppression, respectively.Citation1 In addition, the WHO has recommended moving to a treatment for all strategy to increase the number of individuals living with HIV who receive ART regardless of CD4 cell count or clinical stage.Citation6 Worldwide, adolescents are falling well short of the targeted testing, ART initiation, and viral suppression goals. In the care continuum, estimates of viral suppression among all adolescents living with HIV are <10%.Citation7,Citation8 The largest drop off in the continuum of care for adolescents is in HIV testing and linkage to care where only 41% know their diagnosis.Citation4,Citation8 The ultimate goal of HIV testing is diagnosing new infections, linking individuals to care, and achieving viral suppression; yet there are significant gaps in evidence-based interventions to improve HIV testing and linkage to care for adolescents.

Adolescents face numerous barriers to HIV testing as indicated in . One of the most common psychological barriers to HIV testing among adolescents is lack of perceived risk.Citation9,Citation10 Other psychological barriers include fear of consequences of a positive test, worries about discrimination and rejection, stigma about HIV, sexual orientation, or gender identity.Citation9,Citation11–Citation17 In addition, there are structural barriers to HIV testing among adolescents including never being offered an HIV test, inconvenient hours, lack of insurance, and parental consent.Citation10,Citation16,Citation18–Citation21 Mistrust of the health care system and perception of poor attitudes of health care providers also hinder HIV testing for adolescents.Citation11 Social factors such as socioeconomic status, gender, and race can also impede HIV testing in adolescents. Interventions to improve HIV testing among adolescents should target these barriers to increase HIV testing and linkage to care.

Table 1 Barriers to HIV testing for adolescents

Improving HIV testing and linkage to care is now recognized as a global health priority, and as a result, several interventions have been developed specifically targeting HIV testing uptake among adolescents.Citation22 We conducted a systematic review of interventions published between 2015 and 2018 targeting HIV testing among adolescents to highlight the lack of evidence-based, successful interventions that find new HIV infections among adolescents and successfully link them to care.Citation23–Citation25

Methods

We performed a systematic review of HIV testing interventions targeting adolescents that were published between January 2015 and April 28, 2018. We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Citation26 We initially searched peer-reviewed journals written in English that were located in PubMed and Google Scholar and published after 2010. We then narrowed our results to those published on or after January 1, 2015. Our target population was adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years. However, we included studies that included individuals outside of this age range provided that the intervention was targeted toward adolescents and young adults. Keywords searched included HIV, testing, and at least one of the following age terms: adolescent, adolescence, teen, youth, or young adults.

In addition, we searched for abstracts presented at the International AIDS Society Conference (IAS) and at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). We were able to search 2015–2018 CROI abstracts, but only 2015–2016 IAS abstracts were available online. Keywords searched included HIV and testing. Abstracts were then screened for at least one of the following age terms: adolescent, adolescence, teen, youth, or young adults.

Potential journal articles were uploaded into Covidence, a non-profit website working with the Cochrane database to improve systematic reviews. (www.covidence.org, Melbourne, Australia) Duplicates were removed. After initial screening of the title and abstract, two authors (BCZ and RJE) independently reviewed potential studies. Conflicts were resolved by reviewing the full text article and discussing inclusion/exclusion criteria. We excluded review articles, studies that did not include an intervention, that did not report primary data for HIV testing, or that were targeting children or adults outside our specified age range of 10–24 years. We then extracted data from the full text articles included in this review.

We used the PRISMA guidelines in assessing the strength of evidence and bias for clinical trials and evaluated random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, and outcome reporting.Citation27 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were considered less biased than pre–post evaluations, and prospective and retrospective observational studies. Interventions that were evaluated and published in peer reviewed journals were considered less biased than abstracts from conference proceedings that could only be judged by study design. Observational studies were evaluated for bias using the GRADE guidelines and included an assessment of eligibility, controls, loss to follow-up, and outcome consistency.Citation28

Results

Description of studies identified

Search results included 4,700 potential articles as indicated in the PRISMA flow-diagram in . We excluded 85 duplicates, as well as 4,393 studies that were not relevant to adolescent HIV testing interventions. We reviewed 222 studies for eligibility based on the above criteria and excluded 194 of them: 95 were published between 2010 and 2014; 39 did not report primary data for HIV testing; 31 did not include an intervention involving adolescent HIV testing; 15 were literature reviews; and 14 were not targeting adolescents. We included 28 articles in our final review. In addition, among the 546 IAS and 292 CROI abstracts, 7 and 1 met our inclusion criteria, respectively. None of these were subsequently published in the literature.

We identified a total of 36 studies for this analysis. We separated the studies into those conducted in high-income countries (a total of 14 studies) and those conducted in low- and middle-income countries (a total of 22 studies) and arranged them by the type of intervention as indicated in . All of the studies from high-income countries took place in the US (N=14)Citation16,Citation29–Citation41 and will be referred to as US from here forward. The low- and middle-income countries included South Africa (N=6),Citation42–Citation47 Kenya (N=4),Citation48–Citation51 Bangladesh (N=2),Citation52,Citation53 Zambia (N=2),Citation45,Citation54 Liberia (N=1),Citation55 Ethiopia (N=1),Citation56 Malawi (N=1),Citation57 Mozambique (N=1),Citation58 Myanmar (N=1),Citation59 Ghana (N=1),Citation60 Indonesia (N=1),Citation61 Zimbabwe (N=1),Citation62 Uganda (N=1),Citation48 and Haiti (N=1)Citation63 with two studies taking place in more than one country.Citation45,Citation48 The interventions were organized into six categories as defined in . The interventions to increase HIV testing among adolescents and young adults consisted of behavioral/educational interventions (N=4)Citation29,Citation30,Citation55,Citation56, alternate venue/self-testing (N=11),Citation31–Citation34,Citation42–Citation45,Citation50,Citation57,Citation58 youth-friendly services (N=2),Citation59,Citation60 technology/mobile health (N=9),Citation16,Citation35–Citation39,Citation49,Citation51,Citation61 incentives (N=3),Citation53,Citation54,Citation62 and peer/community-based interventions (N=7).Citation40,Citation41,Citation46–Citation48,Citation52,Citation63 The median sample size was 613 individuals (inter-quartile range=261–2,169). The types of studies included RCTs (N=13),Citation29,Citation31,Citation36,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation55,Citation60,Citation62 observational studies (N=15),Citation16,Citation32–Citation35,Citation41,Citation44,Citation58,Citation61 and quasi-experimental/pre–post evaluations (N=8).Citation30,Citation37,Citation40,Citation46,Citation52,Citation54,Citation56,Citation59

Table 2 Interventions to increase HIV testing among adolescents, published between January 1, 2015, and April 28, 2018

Table 3 Categories of HIV testing interventions

Among the studies in the US, three studies contained information on new HIV diagnoses (ranging from 0.6% to 11.3% with a median of 3.2%).Citation32,Citation34,Citation41 All contained information on linkage to care (ranging from 85% to 100%). In low- and middle-income countries, nine studies included information on new HIV infections (ranging from 0.6% to 9.4% with a median of 3.4%).Citation3,Citation43–Citation45,Citation48,Citation50,Citation53,Citation56,Citation57 Of these, three included information on the number linked to care (ranging from 50% to 100% with an absolute of 97% [94/97]).Citation53,Citation57,Citation63

Bias assessment

Of the 36 studies included in our review, 13 were RCTs and 23 were observational studies.Citation16,Citation30,Citation32–Citation35,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44,Citation46,Citation52,Citation54,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61 Three of the RCTsCitation39,Citation42,Citation62 and five of the observational studiesCitation43,Citation44,Citation52,Citation54,Citation61 were presented in abstracts; these studies were excluded from the risk of bias assessment due to insufficient information. Five of the remaining observational studies were pre–post evaluations of an intervention.

Of the remaining ten RCTs, both random sequence generation and allocation concealment were discernible for four studies from their study methods.Citation36,Citation51,Citation55,Citation60 Two studies reported random sequence generation only.Citation31,Citation38 Four RCTs did not report either random sequence generation or allocation concealment.Citation29,Citation45,Citation47,Citation49 Given the nature of the interventions, blinding of participants and personnel was rarely possible and was reported in only one RCT.Citation38 In that study, only participants were blinded to arm allocation and blinding of outcome assessors was not reported. All RCTs report HIV testing outcomes as predefined primary or secondary outcomes.

All of the remaining 17 observational studies reported eligibility criteria that were applied consistently for all participants. Only one observational study included a control group.Citation59 Four observational studies reported loss to followup data.Citation16,Citation30,Citation40,Citation56 Loss to follow-up rates ranged from 16% to 43%. Implementation challenges were noted for higher loss to follow-up rates.Citation40,Citation56

Interventions

Below we report summaries of the individual interventions designed to increase HIV testing among adolescents separated by intervention category (behavioral/educational, alternative venue/self-testing, technology/mobile health, incentives, youth-friendly services, or peer/community) and country category (high-income versus low- and middle-income countries). Within each intervention category, interventions are listed beginning with the least biased (ie, RCTs followed by pre–post evaluations and observational studies). Interventions published in only abstract form are reported last.

Behavioral/educational interventions (N=4)

There were two interventions from the US that provided a combination of educational material and behavioral interventions targeting adolescents interacting with the criminal justice systemCitation29,Citation30 with one RCT.Citation29 Letourneau et al randomized 105 adolescents attending juvenile drug court to receive standard care compared to risk reduction therapy.Citation29 The intervention involved adolescent-parent dyads in 24 weekly, 60–90 minute sessions involving cognitive behavior therapy and behavior management training with contingency-contracting with a point earning system. At the end of the study, there was no difference in HIV testing in the intervention group (25%) compared to those in standard care (14%) (95% CI 0.49–9.36). This RCT did not report random sequence generation, allocation concealment, or blinding.

In an uncontrolled observational study, Donenberg et al enrolled 54 adolescents aged 13–17 years who had been arrested into the program Preventing HIV/AIDS among Teens (PHAT life), which used group format role plays, videos, and games as an HIV prevention program.Citation30 There was no change in HIV testing among females, while there was a significant increase in testing from 19% at baseline to 41% (P=0.004) at the end of the intervention for males. Both programs were labor intensive, required multiple visits over time and did not significantly increase HIV testing for the defined populations at the end of the program nor did they report the number of new HIV infections diagnosed.

In low- and middle-income countries, two studies provided educational materials and behavioral interventionsCitation55,Citation56 with one RCT.Citation55 In Liberia, 1,052 out-of-school adolescents and young adults aged 15–35 years were randomized to receive standard care versus HealthyActions, a 6-day intensive group learning on sexual and reproductive health.Citation55 At the completion of the study, participants in the control group (42%) were less likely to undergo HIV testing (OR 0.45; 95% CI 0.38–0.53; P<0.001) than the intervention group (88%). This RCT included both random sequence generation and allocation concealment but was not blinded.

A separate non-controlled observational study in Ethiopia enrolled 730 adolescents aged 15–18 years in a 3-month client-centered, counselor-delivered psychosocial intervention that involved individual, group, and creative arts therapy counseling sessions.Citation56 At the end of the study, both females (AOR 1.8; 95% CI 1.13–2.97) and males (AOR 7.3; 95% CI 2.6–20.7) were more likely to have received an HIV test compared to before enrollment. The authors did not report on the number who tested positive or linkage to care. Both of these interventions were labor and training intensive and required multiple visits over time.

Alternate venues/self-testing (N=11)

In the US, there were four studies involving alternative venue testing strategies for adolescentsCitation31–Citation34 with only one RCT.Citation31 Merchant et al randomized 425 MSM aged 18–24 to perform an oral rapid self-test, self-mail in blood test, or testing at a local medical facility.Citation31 Of those enrolled, only 54% completed their assigned test. Oral self-testing (62%) and facility-based testing (56%) were superior (P<0.01 each) to mail in blood testing (40%). This RCT reported random sequence generation but did not report allocation concealment or blinding nor did they report the number of HIV diagnoses or linkage to care.

The alternative strategies investigated by the non-RCT studies included testing on campus at historically black colleges and universities,Citation32 opt-out testing at family planning clinics,Citation33 and targeted testing tailored to sexual minority men.Citation34 All of these strategies reported increased HIV testing among adolescents. An observational study evaluating the provision of HIV testing on campus among 2,385 students attending historically black colleges and universities over a 2-year period detected new HIV infections in 0.6% of those tested.Citation32 The investigators were able to link 100% (N=15) of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV to care. A separate observational study of 3,301 sexual minority men of color aged 13–24 found that targeted testing detected the highest number of new HIV infections (6.3%) compared to universal testing (0.1%) and combination of universal and targeted testing (5.6%).Citation34 This study was not controlled or blinded, and did not report on loss to follow-up. A retrospective analysis evaluated the historical effect of opt-out testing compared to opt-in testing among 34,299 individuals aged 13–23 years attending family planning clinics.Citation33 They found a 50% increase in HIV testing during the opt-out period with 0.3% new HIV diagnoses.

In low- and middle-income countries, there were seven studies evaluating alternative HIV testing strategiesCitation42–Citation45,Citation50,Citation57,Citation58 with two RCTs.Citation42,Citation45 A community RCT in Zambia and South Africa involving 15,456 adolescents aged 15–19 years found that door-to-door testing had high uptake (81%) with 1.6% of those tested newly diagnosed with HIV.Citation45 This RCT did not include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, or blinding. In South Africa, an RCT involving 284 females aged 18–24 years showed that home-based self-testing had higher uptake (97%) than referrals to local clinic (48%) (RR 2.00, 95% CI 1.66–2.40).Citation42 This study was reported in abstract form.

There were five non-RCT studies that evaluated alternative venue HIV testing among adolescents.Citation43,Citation44,Citation50,Citation57,Citation58 In an observational study of 496 individuals aged 16–20 years from Mozambique, uptake of oral self-testing was 60% with 1.7% newly diagnosed with HIV.Citation58 A prospective, observational study of 165 adolescents aged 15–24 years in Malawi evaluated untested adolescents with known HIV-infected adult family members by use of household testing and found 9.7% new HIV infections with 77% successfully linking to care.Citation57 A prospective, observational study offering HIV testing to 1,490 symptomatic youth aged 18–29 years presenting to pharmacies in Kenya found low uptake for testing (24%); however, of those tested, 4% were newly diagnosed with HIV.Citation50 A prospective, observational analysis of 4,800 adolescents in South Africa aged 10–19 years evaluated three testing strategies: index client trailing, door-to-door testing, and campaign testing at events.Citation43 In this study, 4,756 (99.1%) agreed to HIV testing. Diagnosing new HIV infections was highest with testing campaigns (9.4%), followed by index client trailing (6.0%) and door-to-door testing (5.9%; P=0.019). Another South African observational study that evaluated 1,285 youth aged 12–24 years utilizing mobile HIV testing trucks specifically targeting adolescents found a high uptake of first-time HIV testers (45.6%) and found 2.7% of individuals testing to be newly diagnosed with HIV.Citation44

Technology/mobile health (N=9)

In the US, there were six technology or mobile health interventionsCitation16,Citation35–Citation39 with three RCTs.Citation36,Citation38,Citation39 Ybarra et al randomized 302 MSM aged 14–18 years to receive a self-esteem control versus Guy2Guy program that involved daily text messaging for 5 weeks providing HIV information, motivation and behavioral skills, the importance of HIV testing, and healthy relationships. Individuals randomized to the intervention were more likely to undergo HIV testing (OR 3.42; 95% CI 1.65–7.09; P=0.001).Citation38 This RCT included random sequence generation but did not report allocation concealment or blinding. Washington et al randomized 142 black MSM aged 18–30 years old to watch five 60-second videos per week that included vignettes from black MSM characters and to participate in reflections using a group chat feature compared to a control group that received standard information via text messaging. Individuals in the intervention group were more likely to undergo HIV testing compared to the control group (OR 7.0; 95% CI 1.72–28.33; P=0.0006).Citation39 This RCT was reported in abstract form. Bauermeister et al randomized 130 MSM aged 15–24 years to use of an online HIV site testing locator or Get Connected!, a tailored online HIV/sexually transmitted infection intervention with a website, where the logo and online materials were designed with input from a youth advisory board.Citation36 When randomized to the intervention or use of an online testing site locator, there was no statistical difference in HIV testing rates in those receiving the full intervention (32%) compared to those receiving the testing locator only (29%, P>0.05 exact not reported). This RCT reported both random sequence generation and allocation concealment. None of these studies reported on the number of new HIV diagnoses or linkage to care.

Among the non-randomized studies in the US evaluating technology, Dowshen et al reported an observational pre/post evaluation of the IknowUshould2 campaign which used traditional media (print/radio) and technology-based media such as websites, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube to promote HIV testing among 1,500 adolescents who interacted with the campaign.Citation37 Over the 9 months of the program, there was a significant increase in visits to a family planning clinic for HIV testing (5.4%–19%; P<0.01). This study did not control for temporal differences or other possible confounding factors. Solorio et al reported an observational evaluation of 50 Latino MSM using the Tu Amigo Pepe intervention, a 16-week campaign in the US that included Spanish-language radio announcements, a website, social media outreach, text message reminders, and a toll-free hotline.Citation16 The intervention did not significantly increase HIV testing (90%) from baseline (82%) (OR 2.0; 95% CI 0.8–5.4; P=0.16). Neither study reported the number of new HIV infections or linkage to care. Aronson et al conducted a tablet-based intervention for 100 young adults aged 18–24 presenting an emergency department who had declined HIV testing.Citation35 After the intervention, 30% of youth tested and 70% agreed to participate in a 12-week program of weekly text messages.

In low- and middle-income countries, there were three interventions using technology or mobile healthCitation49,Citation51,Citation61 including two RCTs.Citation49,Citation51 In Kenya, a randomized text messaging trial involving 600 women aged 18–24 found that women in the intervention group were more likely (67%) to receive HIV testing within 6 months compared to control (51%) (HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.28–1.92).Citation49 This RCT did not include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, or blinding nor did they report the number of new HIV diagnoses. Another RCT in Kenya randomized 410 individuals aged 18–19 years who were evaluated for acute HIV infection to receive appointment reminders via text message compared to enhanced reminders including dated appointment cards, text message reminders, and phone call reminders to increase repeat HIV testing.Citation51 Repeat HIV testing was 41% in the standard group and 59% in the enhanced group (RR 1.4; 95% CI 1.2–1.7). This RCT reported both random sequence generation and allocation concealment but did not report the number of new HIV diagnoses.

In a retrospective observational study from Indonesia, a combination intervention that included key-population-friendly services and outreach with an online communication forum found a 66% increase in HIV testing compared to baseline and a 67% increase in those receiving ART compared to baseline.Citation61

Incentives (N=3)

Three studies involved interventions that provided incentives to adolescents for undergoing HIV testing, all of which were conducted in low- and middle-income countries: Bangladesh,Citation53 Zambia,Citation54 and ZimbabweCitation62 with only one RCT.Citation62 Dakshina et al randomized 2,796 individuals aged 8–17 years in Zimbabwe into three arms: standard of care (no incentive) versus a prize draw (6% chance of getting $10, 7% chance of getting $5, and 90% of getting $0) versus a guaranteed monetary incentive of $2.Citation62 Overall 35.7% of individuals were tested: 15% in the standard of care; 37% in prize draw; 48% in monetary incentive. The investigators identified 11 new HIV infections: 4 (0.3%) in the monetary incentive arm, 7 (0.8%) in the prize-draw arm, and 0 in the standard of care arm. This RCT was reported in abstract form; therefore, a full bias assessment could not be conducted.

An observational pre/post evaluation in Zambia evaluated 1,813 orphans and vulnerable children aged 11–17 years who participated in the STEPS program (Sustainability through Economic Strengthening, Prevention and Support).Citation54 Individuals enrolled in the program were more likely to have had an HIV test after the program (28%) compared to prior to the intervention (21%). The authors did not report the number of infections identified or linkage to care. An observational study in Bangladesh evaluated 239 MSM and transgender individuals aged 15–24 years in using a voucher system to access HIV testing.Citation53 Of the vouchers distributed, 160 (76%) were returned for testing and 1 (0.6%) individual was found to be HIV infected and subsequently linked to care.

Youth-friendly services (N=2)

There were two interventions involving the use of youth-friendly services to improve HIV testing among adolescents, both in low- and middle-income countries: MyanmarCitation59 and GhanaCitation60 with one RCT.Citation60 A community randomized trial in Ghana evaluated 2,664 adolescents aged 15–17 years who participated in youth-friendly health services, school-based curriculum, outreach, and community mobilization with health-worker training in youth-friendly service compared to control with community mobilization and youth-friendly services only.Citation60 Compared to the control, adolescents receiving the full curriculum had a 9.7% increase in HIV testing, which was not statistically significant (OR 1.16; 95% CI 0.85–1.58). This RCT reported both random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

A non-randomized, controlled study in Myanmar evaluated 613 MSM aged 15–24 years who participated in the Link Up intervention compared to control townships.Citation59 The intervention consisted of community and clinic-based youth-friendly services and included peer education, outreach, and a youth-/MSM-friendly clinic. HIV testing increased from 45% to 57% in the intervention group and was unchanged at 29% in the control group (OR 1.45; 95% CI 0.66–3.17). Neither study reported on the number of new HIV diagnoses during the intervention nor did they discuss linkage to care.

Peer/community interventions (N=7)

In the US, there were two non-randomized, non-controlled studies that evaluated community interventions to increase HIV testing among adolescents. Mpowerment, a community-level mobilization intervention targeting MSM of color aged 18–29 years, found increased testing from 54% at baseline to 70% at 6 months (P<0.001), but it did not report the number of newly diagnosed or linked to care.Citation40 Metropolitan Atlanta Community Adolescent Rapid Testing Initiative (MACARTI) combined non-traditional venue HIV testing, motivational interviewing, and case management targeting youth and identified 11.3% of testers with new HIV infections, 96% linked to care compared to 57% under standard of care (P<0.001).Citation41

In low- and middle-income countries, five studies assessed community- or peer-focused interventionsCitation46–Citation48,Citation52,Citation63 with one RCT.Citation47 A community randomized trial in South Africa evaluated the Grassroot Soccer program that included trained coaches, educational/vocational training, and use of rapid HIV diagnostics. Among the 142 males, the program did not increase HIV testing (29%) compared with delayed enrollment into the program (24%).Citation47 This RCT did not report random sequence generation, allocation concealment, or blinding.

In a separate observational study of the Grassroot Soccer intervention among 1,953 females, 69% of participants tested for HIV; however, there was no comparison or control group.Citation46 Neither study reported on the number of new HIV diagnoses or linkage to care. In Bangladesh, an observational study of the Link Up peer outreach program targeted HIV testing among 1,005 young adult female sex workers working in brothels, but it did not find a significant difference in HIV testing in brothels that had the intervention compared to those that did not participate in the intervention.Citation52 In Haiti, an observational evaluation of a community-based adolescent HIV testing campaign tested 3,348 individuals, of whom 98% offered testing.Citation63 They diagnosed 89 (2.7%) new HIV infections, all of which were linked to the clinic the same day. In Uganda and Kenya, an observational study of a combination approach of community-based testing followed by home-based HIV testing for community members not participating in the campaign tested 86,421 (88%) of adolescents.Citation48 The authors reported that 1,843 (2.1%) individuals were newly diagnosed with HIV; however, they did not report on linkage to care.

Discussion

In this systematic review of HIV testing interventions among adolescents in high- versus low-/middle-income settings, we found 36 studies including 13 RCTs; yet only six studies discussed linkage to care. The primary purpose of screening for any disease is early diagnosis, so that diagnosed individuals can be promptly treated; this is true for HIV testing. Therefore, it is important that interventions to increase HIV testing not only address barriers to HIV testing but also include methods to effectively link newly diagnosed individuals to care.

Interventions that use technology and mobile health can address psychological barriers such as perceived risk, stigma, disclosure, and fear of rejection to increase HIV testing in adolescents. In the US, there were two RCTs and one pre–post evaluation that evaluated interventions using mobile health and technology to target key populations that significantly increased HIV testing among adolescents.Citation37–Citation39,Citation64 In low- and middle-income countries, two RCTs and one retrospective observational study found that text messaging interventions targeting high-risk key populations significantly increased HIV testing among adolescents.Citation49,Citation51,Citation61 In most settings, adolescents and young adults found text messaging and mobile health technology interventions acceptable and feasible.Citation35–Citation39,Citation65–Citation68 However, these interventions did not address structural barriers to HIV testing and none of the nine studies reported the numbers of new HIV diagnoses or linkage to care. Linking newly HIV diagnosed individuals is critical to improving the continuum of care among adolescents living with HIV.Citation7,Citation8

Non-traditional HIV testing venues and oral self-testing can overcome structural barriers such as inconvenience, insurance, and parental consent to improve HIV testing among adolescents.Citation69 In the US, one RCT and three observational studies found high levels of acceptability, but they offered limited data on linkage to care, which is particularly important for alternative venue testing.Citation31–Citation34,Citation69 Oral self-testing was an acceptable HIV testing method among adolescents and could be a method employed to expand HIV testing programs; however, there are limited data on linkage to care after self-testing among adolescents.Citation31,Citation58 Within traditional health care venues, opt-out testing appears to improve HIV testing among adolescents compared to opt-in testing and may increase HIV testing over provider-initiated counseling and testing in high-prevalence areas.Citation33,Citation70,Citation71 In low- and middle-income countries, door-to-door and mobile HIV testing was found to be feasible, acceptable, and led to large numbers of adolescents obtaining HIV testing; however, data on linkage to care is absent in those studies.Citation43–Citation45 In Malawi, door-to-door contact tracing of children born to HIV-infected mothers was a high yield method for detecting perinatal HIV in children and younger adolescents and could be expanded to other high HIV prevalence countries.Citation57 Providing flexible, alternative strategies outside of traditional health care settings appears to be an acceptable, feasible, and effective method of increasing HIV testing among adolescents in the US and low- and middle-income countries. In low-and middle-income countries, alternative testing sites such as home self-testing, in-home door-to-door testing, testing campaigns, and pharmacy-based testing appear to be acceptable and feasible alternatives for HIV testing among adolescents; however, little is known about linkage to care after new HIV diagnosis in alternative venues. Of the eleven interventions involving alternative venue HIV testing, only two evaluated linkage to care, limiting the generalizability of these approaches.Citation32,Citation57

Community testing events and mobilization have the potential to overcome structural and psychosocial barriers by easing access, making testing normative, and providing social support; therefore, they have the ability to test large numbers of individuals and can be used to target high-risk, key populations.Citation40,Citation41,Citation46,Citation48,Citation52,Citation57,Citation63 The only RCT in this category did not find efficacy in increasing HIV testing.Citation47 However, six observational studies reported high levels of HIV testing in community interventions. In addition, two interventions reported successful linkage to care after HIV testing, making this an important component for future HIV testing modalities for adolescents.Citation41,Citation57,Citation63

Other HIV testing interventions had mixed results and lower quality evidence for increasing HIV testing among adolescents. Interventions that involved behavioral change or education in the US were labor and resource intensive and showed variable results.Citation29,Citation30 These interventions appeared to be more effective in low- and middle-income countries compared to the US; however, none of these studies discussed the number of newly diagnosed HIV infections nor the number linked to care. Offering incentives for HIV testing among adolescents can address motivation for HIV testing but does not overcome many structural or psychosocial barriers to HIV testing, and sustainability may be challenging.Citation53,Citation54,Citation62 In addition, there is limited data on the effectiveness of incentives on linkage to care after HIV testing. The specific use of youth-friendly testing facilities can address some structural and psychosocial barriers to HIV testing; however, these interventions did not have statistically superior effects compared to traditional testing sites.Citation59,Citation60

Though critical to informing the implementation and scale-up of effective interventions, none of the studies reported resource utilization or costs related to HIV testing or the intervention. With resource utilization and cost data, health policy models can project the long-term impact of interventions beyond the time-horizon of traditional studies. This type of analysis is particularly important when considering testing interventions among youth, in whom the effects of HIV infection and treatment may not manifest for years or decades.Citation5 Few studies have reported on the cost-effectiveness of adolescent-specific prevention or testing interventions.Citation72–Citation76 Such information is invaluable for policymakers to understand optimally deploying combinations of universal and targeted testing in specific settings and warrants more study moving forward.Citation77

Current studies are exploring alternative methods and venues to improve HIV testing and linkage to care among high-risk adolescents.Citation78 Mpower is an ongoing community-level intervention in the targeting young MSM using peer educators to engage high-risk youth to increase HIV testing.Citation79 Other investigators are exploring the use of oral, self-testing with video counseling for transgender youth in the US.Citation80 In Kenya, a large-scale study is evaluating alternative testing venues (community versus home) and testing modalities such as oral self-testing, home testing, mobile testing, or facility-based testing.Citation81 Results of these studies may add valuable information for the development of multicomponent interventions to increase HIV testing among adolescents.

Future research should also focus on expanding the geographic reach of interventions for HIV testing among adolescents and young adults. In particular, this review did not identify any recently published interventions to increase HIV testing in Latin America or in high-income countries other than the US. Although the majority of HIV infections among adolescents occur in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV affects adolescents globally. It is important that effective interventions are identified that address culture-specific barriers and target local at-risk populations.Citation3

Conclusion

To diagnose more HIV infections among adolescents, it is important to target high-risk populations, minimize barriers to HIV testing, and make testing easier and more widely available. One intervention is unlikely to address all of the barriers to HIV testing among adolescents and would be unlikely to succeed across all settings. Therefore, future interventions should utilize multiple components and expand on the successful use of mobile health technology, alternate venue testing, and community mobilization while stressing the importance of linkage to care. High-quality RCTs are needed to identify optimal combinations of interventions that increase HIV testing among adolescents while focusing on diagnosing new HIV infections and providing linkage to care.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

BCZ received funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (No. K23MH114771) for his role as principal investigator. JEH received funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (No. K24MH114732) for her role as principal investigator. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDSAmbitious treatment targets: writing the final chapter of the AIDS epidemicUNAIDS Geneva2015

- United Nations Children’s FundTowards an AIDS-free Generation Children and AIDSNew York, NYUNICEF2013

- IdelePGillespieAPorthTEpidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: current status, inequities, and data gapsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201466Suppl 2S14415324918590

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)HIV and Youth2018 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and AdolescentsGuidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIVServices Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services2018

- World Health OrganizationGuideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIVGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2015

- ZanoniBCArcharyMBuchanSKatzITHabererJESystematic review and meta-analysis of the adolescent and young adult HIV continuum of care in South Africa: the cresting waveBMJ Global Health201613e000004

- ZanoniBCMayerKHThe adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparitiesAIDS Patient Care STDS201428312813524601734

- de WitJBAdamPCTo test or not to test: psychosocial barriers to HIV testing in high-income countriesHIV Med20089Suppl 2202218557865

- PeraltaLDeedsBGHipszerSGhalibKBarriers and facilitators to adolescent HIV testingAIDS Patient Care STDS200721640040817594249

- Sam-AguduNAFolayanMOEzeanolueEESeeking wider access to HIV testing for adolescents in sub-Saharan AfricaPediatr Res201679683884526882367

- LiHWeiCTuckerJBarriers and facilitators of linkage to HIV care among HIV-infected young Chinese men who have sex with men: a qualitative studyBMC Health Serv Res201717121428302106

- LogieCHNewmanPAWeaverJRoungkraphonSTepjanSHIV-Related stigma and HIV prevention uptake among young men who have sex with men and transgender women in ThailandAIDS Patient Care STDS20163029210026788978

- MwangiRWNgurePThigaMNgureJFactors influencing the utilization of Voluntary Counselling and Testing services among university students in KenyaGlob J Health Sci201464849324999153

- PharrJRLoughNLEzeanolueEEBarriers to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men (MSM): experiences from Clark County, NevadaGlob J Health Sci201587917

- SolorioRNorton-ShelpukPForehandMTu Amigo Pepe: evaluation of a multi-media marketing campaign that targets young latino immigrant MSM with HIV testing messagesAIDS Behav20162091973198826850101

- StraussMRhodesBGeorgeGA qualitative analysis of the barriers and facilitators of HIV counselling and testing perceived by adolescents in South AfricaBMC Health Serv Res20151525026123133

- CataniaJADolciniMMHarperGWBridging barriers to clinic-based HIV testing with new technology: translating self-implemented testing for African American youthTransl Behav Med20155437238326622910

- DollMFortenberryJDRoselandDMcauliffKWilsonCMBoyerCBLinking HIV-negative youth to prevention services in 12 U.S. cities: barriers and facilitators to implementing the HIV prevention continuumJ Adolesc Health201862442443329224988

- HydenCAllegranteJPCohallATHIV testing sites’ communication about adolescent confidentiality: potential barriers and facilitators to testingHealth Promot Pract201415217318023966274

- JenningsLMathaiMLinnemayrSEconomic context and HIV vulnerability in adolescents and young adults living in urban slums in Kenya: a qualitative analysis based on scarcity theoryAIDS Behav20172192784279828078495

- WongVJMurrayKRPhelpsBRVermundSHMccarraherDRAdolescents, young people, and the 90-90-90 goals: a call to improve HIV testing and linkage to treatmentAIDS201731Suppl 3S191S428665876

- ArnoldEARebchookGMKegelesSM‘Triply cursed’: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay menCult Health Sex201416671072224784224

- GaoTYHoweCJZulloARMarshallBDLRisk factors for self-report of not receiving an HIV test among adolescents in NYC with a history of sexual intercourse, 2013 YRBSVulnerable Child Youth Stud201712427729129057006

- HelleringerSUnderstanding the adolescent gap in HIV testing among clients of antenatal care services in West and Central African CountriesAIDS Behav20172192760277327734167

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGGroup PPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med200967e100009719621072

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationPLoS Med200967e100010019621070

- GuyattGHOxmanADVistGGRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias)J Clin Epidemiol201164440741521247734

- LetourneauEJMccartMRSheidowAJMauroPMFirst evaluation of a contingency management intervention addressing adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors: risk reduction therapy for adolescentsJ Subst Abuse Treat201772566527629581

- DonenbergGREmersonEMackesy-AmitiMEUdellWHIV-risk reduction with juvenile offenders on probationJ Child Fam Stud20152461672168426097376

- MerchantRCClarkMALiuTComparison of home-based oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing versus mail-in blood sample collection or medical/community HIV testing by young adult black, Hispanic, and white MSM: results from a randomized trialAIDS Behav201822133734628540562

- HollidayRCZellnerTFrancisCBraithwaiteRLMcgregorBBonhommeJCampus and community HIV and addiction prevention (CCHAP): an HIV testing and prevention model to reach young African American adultsJ Health Care Poor Underserved2017282S698028458265

- BuziRSMadanayFLSmithPBIntegrating routine HIV testing into family planning clinics that treat adolescents and young adultsPublic Health Rep2016131Suppl 113013826862238

- MillerRLBoyerCBChiaramonteDEvaluating testing strategies for identifying youths with HIV infection and linking youths to biomedical and other prevention servicesJAMA Pediatr2017171653253728418524

- AronsonIDClelandCMPerlmanDCMobile screening to identify and follow-up with high risk, HIV negative youthJ Mob Technol Med20165191827110294

- BauermeisterJAPingelESJadwin-CakmakLAcceptability and preliminary efficacy of a tailored online HIV/STI testing intervention for young men who have sex with men: the Get Connected! programAIDS Behav201519101860187425638038

- DowshenNLeeSMatty LehmanBCastilloMMollenCIknowUshould2: Feasibility of a Youth-Driven Social Media Campaign to Promote STI and HIV Testing Among Adolescents in PhiladelphiaAIDS Behav201519Suppl 210611125563502

- YbarraMLPrescottTLPhillipsGL2ndBullSSParsonsJTMustanskiBPilot RCT Results of an mHealth HIV Prevention Program for Sexual Minority Male AdolescentsPediatrics20171401

- WashingtonTAApplewhiteSUsing social media as a platform to direct young Black men who have sex with men to an intervention to increase HIV testingAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- ShelleyGWilliamsWUhlGAn Evaluation of Mpowerment on Individual-Level HIV Risk Behavior, Testing, and Psychosocial Factors Among Young MSM of Color: The Monitoring and Evaluation of MP (MEM) ProjectAIDS Educ Prev2017291243728195781

- Camacho-GonzalezAFGillespieSEThomas-SeatonLThe Metropolitan Atlanta community adolescent rapid testing initiative study: closing the gaps in HIV care among youth in Atlanta, Georgia, USAAIDS201731Suppl 3S267S7528665885

- PettiforAKahnKKimaruLMayakayakaZHIV Self-testing Increases Testing in Young South African Women: Results of an RCTConference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI)2018Boston, MA

- FattiGManjeziNShaikhNMothibiEOyebanjiOGrimwoodAAn innovative combination strategy to enhance HIV testing amongst adolescents in South AfricaAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- Rousseau-JemwaESmithPZakariyaDBekkerLGCommunity-based HIV testing for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: results from a mobile clinic initiativeAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- ShanaubeKSchaapAHPTN 071 (PopART) Study TeamCommunity intervention improves knowledge of HIV status of adolescents in Zambia: findings from HPTN 071-PopART for youth studyAIDS201731Suppl 3S221S3228665880

- HershowRGannettKMerrillJUsing soccer to build confidence and increase HCT uptake among adolescent girls: A mixed-methods study of an HIV prevention programme in South AfricaSport Soc20151881009102226997967

- Rotheram-BorusMJTomlinsonMDurkinABairdKDecellesJSwendemanDFeasibility of Using Soccer and Job Training to Prevent Drug Abuse and HIVAIDS Behav20162091841185026837624

- KadedeKRuelTSEARCH teamIncreased adolescent HIV testing with a hybrid mobile strategy in Uganda and KenyaAIDS2016301422212226

- NjugunaNNgureKMugoNThe Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention and Reproductive Health Text Messages on Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing Among Young Women in Rural Kenya: A Pilot StudySex Transm Dis201643635335927200519

- MugoPMPrinsHAWahomeEWEngaging young adult clients of community pharmacies for HIV screening in Coastal Kenya: a cross-sectional studySex Transm Infect201591425725925487430

- MugoPMWahomeEWGichuruENEffect of Text Message, Phone Call, and In-Person Appointment Reminders on Uptake of Repeat HIV Testing among Outpatients Screened for Acute HIV Infection in Kenya: A Randomized Controlled TrialPLoS One2016114e015361227077745

- HossainSSultanaNHossainTZiemanBRoySPilgrimNDoes peer outreach increase HIV testing self-efficacy and uptake? Evaluation of the Link Up program in Bangladesh brothelsAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- OyewaleTOAhmedSAhmedFThe use of vouchers in HIV prevention, referral treatment, and care for young MSM and young transgender people in Dhaka, Bangladesh: experience from ‘HIM’ initiativeCurr Opin HIV AIDS201611Suppl 1S37S4526945145

- ChapmanJNgungaMChariyevaZSimbayaJKamwangaJKairaWImproved HIV testing uptake, food security and reduced violence among orphans and vulnerable children in Zambia: the impact of using baseline data to define program scopeIAS 2015 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention2015Vancouver, Canadad

- FirestoneRMoorsmithRJamesSIntensive Group Learning and On-Site Services to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Young Adults in Liberia: A Randomized Evaluation of HealthyActionsGlob Health Sci Pract20164343545127688717

- JaniNVuLKayLHabtamuKKalibalaSReducing HIV-related risk and mental health problems through a client-centred psychosocial intervention for vulnerable adolescents in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaJ Int AIDS Soc2016195 Suppl 42083227443267

- AhmedSSabelliRASimonKIndex case finding facilitates identification and linkage to care of children and young persons living with HIV/AIDS in MalawiTrop Med Int Health20172281021102928544728

- HectorJDaviesMADekker-BoersemaJAcceptability and performance of a directly assisted oral HIV self-testing intervention in adolescents in rural MozambiquePLoS One2018134e019539129621308

- AungPPRyanCBajracharyaAEffectiveness of an Integrated Community- and Clinic-Based Intervention on HIV Testing, HIV Knowledge, and Sexual Risk Behavior of Young Men Who Have Sex With Men in MyanmarJ Adolesc Health2017602S2S45S53

- AninanyaGADebpuurCYAwineTWilliamsJEHodgsonAHowardNEffects of an adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention on health service usage by young people in northern Ghana: a community-randomised trialPLoS One2015104e012526725928562

- NevendorffLMukaromahYNurhalinahAPerdanaSWidodoWTasyaIAReaching unreachable population: multi-collaboration framework to improve young key population access towards HIV-related services in demonstration site of Bandung, IndonesiaAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- DakshinaSBandasonTDauyaEKranzerKMchughGMunyatiSThe impact of incentives on uptake of HIV testing among adolescents in a high HIV prevalence settingAIDS 2016 21st International AIDS Conference2016Durban, South Africa

- ReifLKRiveraVLouisBCommunity-Based HIV and Health Testing for High-Risk Adolescents and YouthAIDS Patient Care STDS201630837137827509237

- TsoLSTangWLiHYanHYTuckerJDSocial media interventions to prevent HIV: A review of interventions and methodological considerationsCurr Opin Psychol2016961026516632

- GarettRSmithJYoungSDA Review of Social Media Technologies Across the Global HIV Care ContinuumCurr Opin Psychol20169566626925455

- BelzerMEKolmodin MacDonellKAdolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of a Cell Phone Support Intervention for Youth Living with HIV with Nonadherence to Antiretroviral TherapyAIDS Patient Care STDS201529633834525928772

- CooperVClatworthyJWhethamJConsortiumEmHealth Interventions To Support Self-Management In HIV: A Systematic ReviewOpen AIDS J20171111913229290888

- Hightow-WeidmanLBMuessigKEBauermeisterJZhangCLegrandSYouth, Technology, and HIV: Recent Advances and Future DirectionsCurr HIV/AIDS Rep201512450051526385582

- MaranoMRSteinRWilliamsWOHIV testing in nonhealthcare facilities among adolescent MSMAIDS201731Suppl 3S261S26528665884

- GovindasamyDFerrandRAWilmoreSMUptake and yield of HIV testing and counselling among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic reviewJ Int AIDS Soc2015182018226471265

- MinniearTDGilmoreBArnoldSRFlynnPMKnappKMGaurAHImplementation of and barriers to routine HIV screening for adolescentsPediatrics200912441076108419752084

- PinkertonSDHoltgraveDRJemmottJBEconomic evaluation of HIV risk reduction intervention in African-American male adolescentsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200025216417211103047

- TaoGRemafediGEconomic evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention for gay and bisexual male adolescentsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol199817183909436764

- NeilanAMDunvilleROcfemiaMCBThe Optimal Age for Screening Adolescents and Young Adults Without Identified Risk Factors for HIVJ Adolesc Health2018621222829273141

- KahnJGKegelesSMHaysRBeltzerNCost-effectiveness of the Mpowerment Project, a community-level intervention for young gay menJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200127548249111511826

- NeilanABFreedbergAJHosekKALandovitzSGWilsonRJWalenskyCMCiaranelloAL RPCost-effecteness of repeat screening in high-risk youthConference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections2018Boston, MAMarch

- AgwuALQuinnTCFinding Youths at Risk for HIV Infection: Targeted Testing, Universal Testing, or Both?JAMA Pediatr2017171651751828418510

- TrialsAC2018 Available from: https://atnweb.org/atnweb/studies

- FenklEAJonesSGOvesJCPanther Mpower: A Campus-Based HIV Intervention for Young Minority Men who Have Sex with MenJ Health Care Poor Underserved2017282S91528458260

- StephensonRMethenyNSharmaASullivanSRileyEProviding Home-Based HIV Testing and Counseling for Transgender Youth (Project Moxie): Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled TrialJMIR Res Protoc2017611e23729183868

- InwaniIChhunNAgotKHigh-Yield HIV Testing, Facilitated Linkage to Care, and Prevention for Female Youth in Kenya (GIRLS Study): Implementation Science Protocol for a Priority PopulationJMIR Res Protoc2017612e179

- FryeVWiltonLAll About Me Study Team“Just Because It’s Out There, People Aren’t Going to Use It.” HIV Self-Testing Among Young, Black MSM, and Transgender WomenAIDS Patient Care STDS2015291161762426376029

- FisherCBFriedALMacapagalKMustanskiBPatient-Provider Communication Barriers and Facilitators to HIV and STI Preventive Services for Adolescent MSMAIDS Behav2018

- BhoobunSJettyAKoromaMAFacilitators and barriers related to voluntary counseling and testing for HIV among young adults in Bo, Sierra LeoneJ Community Health201439351452024203408