Abstract

Both the prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, Gardasil® and Cervarix®, are licensed for the prevention of cervical cancer in females, and Gardasil is also licensed for the prevention of genital warts and anal cancer in both males and females. This review focuses on the uptake of these vaccines in adolescent males and females in the USA and the barriers associated with vaccine initiation and completion. In the USA in 2009, approximately 44.3% of adolescent females aged 13–17 years had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, but only 26.7% had received all three doses. In general, the Northeast and Midwest regions of the USA have the highest rates of HPV vaccine initiation in adolescent females, while the Southeast has the lowest rates of vaccine initiation. Uptake of the first dose of the HPV vaccine in adolescent females did not vary by race/ethnicity; however, completion of all three doses is lower among African Americans (23.1%) and Latinos (23.4%) compared with Caucasians (29.3%). At present, vaccination rates among adolescent females are lower than expected, and thus vaccine models suggest that it is more cost-effective to vaccinate both adolescent males and females. Current guidelines for HPV vaccination in adolescent males is recommended only for “permissive use,” which leaves this population out of routine vaccination for HPV. The uptake of the vaccine is challenged by the high cost, feasibility, and logistics of three-dose deliveries. The biggest impact on acceptability of the vaccine is by adolescents, physicians, parents, and the community. Future efforts need to focus on HPV vaccine education among adolescents and decreasing the barriers associated with poor vaccine uptake and completion in adolescents before their sexual debut, but Papanicolau screening should remain routine among adults and those already infected until a therapeutic vaccine can be developed.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common causes of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in both men and women worldwide, including the USA.Citation1 Exposure to HPV is common among adolescents aged 13–19 years soon after initiation of intercourse.Citation2,Citation3 Studies from a cohort of 19-year-old college females have shown that the cumulative incidences of HPV infection after a 24-month period are similar between virgins who become sexually active and nonvirgins, at 38.8% and 38.9%, respectively.Citation3 In the USA, 24% of adolescents are sexually active by 15 years, 40% by 16 years, and 70% by 18 years.Citation4 Number of sexual partners is a major risk factor for HPV acquisition, with 5.7% and 20.2% of ninth and twelfth graders, respectively, have had more than four sexual partners.Citation5 Of the estimated 20 million persons infected with HPV in the USA, about half are aged 15–24 years; another 6.2 million new cases (4.6 million aged 15–24 years) are diagnosed annually.Citation6 The rate of subclinical HPV infection is much higher in adolescents (12%–56%)Citation7–Citation10 compared with older women (2%–7%),Citation6,Citation11 with cumulative prevalence rates as high as 82% in specific subpopulations.Citation12 While adolescents have a much lower incidence of cervical or other HPV-related cancers, they are still affected by HPV-related sequelae, like genital warts, which are estimated to effect 3% of sexually active adolescents.Citation13 The importance of the two prophylactic vaccines, currently approved and available, is paramount. However, barriers to uptake exist, and this review focuses on these issues, in the context of the USA.

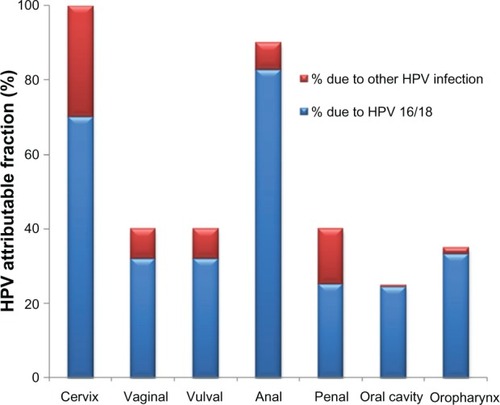

Long-term persistence of HPV is the key factor in the development of 5% of all human cancers.Citation14 Epidemiological and virological data demonstrate that oncogenic HPVs are the primary (and necessary) causal agents of cervical cancer.Citation15,Citation16 HPV-DNA is present in 99.7% of all cervical carcinomas, and HPV types 16, 18, 45, and 31 are the most predominant.Citation17–Citation19 Both of the currently available vaccines contain the two most common HPV types 16 and 18. HPV infection is associated with other cancers besides cervical cancer, as evidenced by the incidence and mortality rates shown in . HPV infection is attributable to 35% of oropharynx, 25% of oral cavity, 40% of penile, 90% of anal, 40% of vulval, 40% of vaginal, and 99.9% of cervical cancers, and oncogenic HPV types 16/18 are responsible for 89%, 98%, 63%, 92%, 80%, 80%, and 70% of all these cancers, respectively ().Citation20 However, there are other HPV types, some also considered oncogenic, not covered by the vaccines that also might contribute to these cancers. Likewise, infection with “benign” or low-risk HPVs that cause genital warts have a life-time acquisition risk of 10% in the USA and a worldwide prevalence of 0.6%–3.0%, which also presents major morbidity and economic cost.Citation21,Citation22

Figure 1 Major cancers attributable to HPV infection. Seven cancers are associated with HPV infection, total attributable risk to any HPV infection is shown with blue color referring to HPV types 16 and 18 and the remaining due to other HPV infection (in red).

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

Table 1 New cases of HPV-related major cancers in the USA and worldwideCitation42,Citation100,Citation101

Although HPV-related cancers generally occur in older women, and not in adolescents (), considering the HPV lifecycle and its attributable fraction to various cancers, any strategy to prevent HPV infection as early as possible seems a major public health priority. HPV-associated cancers and genital warts are potentially preventable by vaccination with the HPV vaccine, which has been shown to be efficacious, specifically against the most oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18. This review summarizes some of the current knowledge about the role and uptake of the HPV vaccine in adolescent health in the USA.

HPV vaccine

On June 8, 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the three-dose quadrivalent (HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18) HPV vaccine, Gardasil® (Merck Sharp and Dohme, Whitehouse Station, NJ), also known as HPV4,Citation23 and on October 16, 2009, the FDA approved the three-dose bivalent (HPV types 16 and 18) vaccine, Cervarix® (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NJ), also known as HPV2.Citation24 Gardasil is currently approved in more than 123 countries and Cervarix in 66 countries.Citation25 Both vaccines are prophylactic and contain virus-like particles of HPV types that stimulate type-specific neutralizing antibodies. Both HPV vaccines have demonstrated better than 90% efficacy () in reducing the risk of precancerous lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and 3, CIN2 and CIN3, respectively) and adenocarcinoma in situ from the targeted HPV vaccine types for up to 5 years.Citation26–Citation28 Gardasil was also shown to be highly efficacious for preventing genital warts in males aged 16–26 years and was licensed by the FDA in 2009, and Gardasil was also licensed by the FDA in 2010 for the prevention of precancerous anal lesions and cancer in males and females aged 16–26 years.Citation29,Citation30 Additional vaccine characteristics and clinical trial data key for licensure by the FDA are described and compared briefly in .

Table 2 Comparison of two HPV vaccines with regard to efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity trial data key to FDA licensureCitation102,Citation103

Initially, vaccine-induced immune titers to the specific HPV types are much higher (10–104 times) than seen after natural infection. However, the minimum anti-HPV titer that confers protective efficacy has not been determined. Immunogenicity data based on geometric mean titers indicate a significantly higher antibody response in younger adolescents (9–15 years) compared with older women (16–26 years).Citation31,Citation32 Antibody levels to type-specific HPV generally peak at 1 month after the third dose, followed by a decline (of one log) until month 18 following vaccination, after which it stabilizes and remains as high as or higher still than that seen after natural infection, but little is known about the long-term duration of these antibody titers. Clinical trial populations have demonstrated sustained immunogenicity for up to 6.4 years following vaccination,Citation28 but an ideal prophylactic vaccine should provide protection for 10–15 years to protect 11–12-year-old adolescents during the period when they are most likely to be exposed and susceptible to HPV infection.Citation33 Additional data on duration of protection and outcomes will be available from ongoing prospective studies, such as the GARDASIL Vaccine Impact in Population Study (VIP), monitored through vaccine registries in women from Nordic countries.Citation34

Additionally, host genes are also important in determining how well people respond to vaccination, and variation in the genes encoding our immune system accounts for much of this vaccine response heterogeneity. Studies of heritability of the pattern of response to several vaccines (for hepatitis B, oral polio, tetanus, and diphtheria) have suggested that significant genetic contributionsCitation35–Citation37 and variation in response, including adverse effects to HPV vaccine, is no less likely to be heritable. To date, little or no research has been conducted on host genetic factors involved in failure or variability of the response to HPV vaccine, primarily because of high antibody titer response in the short duration of follow-up studies, and the long-term differential response and effects are yet to be determined.

Current recommendations for vaccination and screening

The 2011 recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedules were approved by the Advisory Committee of Immunization Practices (ACIP), American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Family Physicians, which are the primary US vaccination councils, and are summarized in . Both Gardasil and Cervarix are recommended for prevention of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions, and females aged 11–12 years are the targeted vaccination age group, but can be administered to females as young as 9 years. These guidelines were updated in 2009 to include permissive vaccination in males with Gardasil for genital warts.Citation38 Because screening before the age of 21 years was found to have little or no impact on the incidence of cervical cancer,Citation39 in June 2009, representatives from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and approximately 25 other organizations revised their guidelines to delay cervical cancer screening until age 21 years.Citation40

Table 3 US HPV vaccine licensure and recommended schedulesCitation23,Citation83,Citation102–Citation105

Cost-effectiveness of vaccine

Through Papanicolaou (Pap) test screening, the rates of cervical cancer have decreased by 70% over the past 50 years. However, the rates of cervical cancer are still high worldwide.Citation41,Citation42 Many of the women who are diagnosed with cervical cancer are either not being treated or are not routinely undergoing screening. The low sensitivity of the Pap test (60%–70%)Citation43 would result in high false-positive rates, so women would be receiving costly additional tests, compounded by the high emotional burden of dealing with these potential precancerous lesions.Citation44 Approximately 55 million Pap tests are performed each year in the USA on adult women, and, of these, about 3.5 million (6%) find abnormal results that require medical follow-up.Citation45 Total direct medical costs associated with cervical cancer prevention and treatments in the USA are estimated to be at least $4 billion per year.Citation46 While the Pap test has been an effective way to keep cervical cancer rates low in the USA, it is not cost-effective, so implementation of the HPV vaccine seems to be a viable alternative. The HPV vaccine could reduce the total direct and indirect costs by preventing primary infection and the development of precancerous lesions and cancers.Citation47 ArmstrongCitation47 and Techakehakij and FeldmanCitation48 recently summarized several models implemented to assess cost-effectiveness of the HPV vaccine. Assuming 90%–100% vaccine efficacy, at least 70% vaccine coverage, and either 10-year or lifetime protection,Citation47 these studies in general have shown a range of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for the HPV vaccine between $16,000 and $27,231 (median $25,400) per quality-adjusted life year gained from preventing HPV genotypes 16 and 18.Citation48 There seems to be consistent positive quality-adjusted life year findings across models, provided sufficient duration of protection, clearly suggesting that routine HPV vaccination of adolescents is cost-effective.

Men also have HPV-related diseases and can transmit the virus to both men and women through sexual activity. HPV infection rates have been reported to be similar between males and females.Citation29 Several studies have reported that the probability of new genital HPV infection among sexually active males within a 12-month period ranges from 0.29–0.39 per 1000 person-months, similar to those in females.Citation49–Citation51 Dunne et al indicated that the prevalence and incidence of HPV are generally similar but vary based on the populations and methodology used to detect infection.Citation52 Given that males can be carriers of HPV, vaccinating them would not only prevent infection in them individually but would increase “herd immunity.” Herd immunity can be achieved only by acceptance and involvement of both genders rather than narrowly targeted populations.Citation53 However, vaccination of males has produced mixed cost-effectiveness results.Citation47 Several studies reported a gain in incremental cost-effectiveness ratios,Citation54,Citation55 while others reported no gain in cost-effectiveness.Citation56 Brisson et al reported male vaccination to be cost-effective when the vaccination rates of young women are low (below 50%), but not when they are high (above 70%).Citation57 Currently, vaccination rates among young women are lower than the expected 70%, based on assumptions in the cost-effectiveness model.Citation47 Therefore, it seems more cost-effective to vaccinate both young males and females under the assumptions made. However, due to the uncertainty in these cost-effective models for males, the ACIP recommended permissive use of the HPV vaccine in males.Citation38 Likewise, the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination in adult women is also uncertain.

Uptake

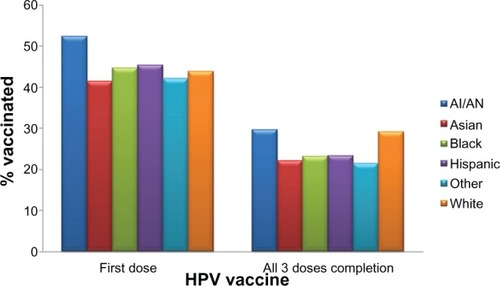

Since 2006, when the Gardasil vaccine was licensed in the USA, approximately 33 million doses have been distributed in the USA.Citation58 In 2009, 17.1% of women aged 19–26 years in the USA had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, an increase of over 10.5% in 2008.Citation59 In adolescent females aged 13–17 years, approximately 44.3% had received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, and 26.7% had received all three doses of the vaccine in the USA in 2009.Citation60 For the first dose of HPV vaccine in adolescents, race/ethnicity seems to make no difference in coverage (). However, compared with those living at or above the poverty level, HPV vaccine initiation is higher among those living below the poverty level (42.5% versus 51.9%).Citation60 Coverage with three doses in adolescents was lower among African Americans (23.1%) and Latinos (23.4%) compared with Caucasians (29.3%), as shown in .Citation60

Figure 2 HPV vaccine coverage (in percent) for 13–17-year-old adolescents by race/ethnicity for at least one dose and for complete three doses. The percent coverage is based on data on either Gardasil® or Cervarix® vaccine among 9621 females. Persons who identified as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders and persons of multiple races were categorized as other.

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; AI, American Indian; AN, Alaskan Natives.

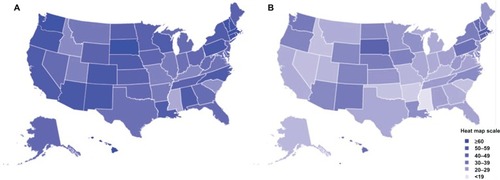

As seen in and , HPV vaccine uptake in adolescent females differs geographically.Citation60 In general, the Northeast and Midwest regions have the highest rates of HPV vaccination initiation () in the USA, while the Southeast has the lowest rates of vaccine initiation. HPV vaccine completion rates (three doses) are significantly lower for the majority of states, except in South Dakota and several Northeastern states (). Of note, it is interesting that states such as Alabama, Louisiana, and California have a high initiation of HPV vaccine compared with other states but have very low vaccine completion ( and ). States with the highest rates of cervical cancer mortality include Mississippi, Arkansas, West Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, and Alabama, which are predominantly in the South/Southeast, and states with the lowest rates of cervical cancer mortality include Massachusetts, Connecticut, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Rhode island, which are in the Northeast and Midwest.Citation61,Citation62 In general, the states with the highest rates of cervical cancer mortality seem to have the lowest vaccine coverage, while the states with the lowest rates of cervical cancer mortality have the highest vaccine coverage.

Figure 3 HPV vaccination uptake in 13–17-year-old adolescents by state in the USA. Estimated percent coverage for (A) first dose of the HPV vaccine and (B) all three doses of the HPV vaccine.

Abbreviation: HPV, human papilloma virus.

Post-licensure HPV male vaccination rates have not been published, because the vaccine licensure and recommendations were not extended to males until 2009. Vaccination of males is important, both because rates of HPV vaccination in females is currently lower than anticipated, and for the reasons discussed above, for achieving herd immunity. Vaccinating only females leaves men who have sex with men (MSM) an extremely at-risk group for HPV-associated malignancies, unprotected. MSM and men who have sex with men and women are more likely to be infected with genital, anal, or oral HPV than men who have sex only with women.Citation51,Citation63,Citation64 The rates of anal cancer in high-risk groups such as MSM are comparable with cervical cancer rates prior to routine screening, and these rates are even higher among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive MSMs.Citation65,Citation66 Additionally, the prevalence of vaccine type HPV infection is high among MSM and men who have sex with men and women; thus, vaccinating this population is very logical. Kim reported that HPV vaccination of MSM may be cost-effective to prevent anal cancer and genital warts, with about $37,830 per quality-adjusted life year gained under the best case scenario.Citation67 Additional convincing cost-effectiveness data, preferably above the minimum benchmark of $50,000, would be required for the ACIP to recommend routine vaccination in this group. Further, targeting this population before sexual onset is difficult due to social stigmatization and unknown sexual orientation, specifically at an early age.

Uptake and recommendations in special populations

HIV population

In 2004 in the USA, there were 4883 HIV diagnoses in the age group 13–24 years, which represents 13% of the total new cases of HIV infection.Citation68 HPV-associated cancers occur frequently in HIV patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).Citation69 Thus, in 1993, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) added cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining condition.Citation70 In the AIDS Malignancy Consortium Protocol 052,Citation71 no adverse events, including in CD4 count and HIV RNA levels, were attributable to quadrivalent HPV vaccination among the 109 HIV-positive men who received at least one dose of vaccine. Seroconversion was observed (98%–100%) for all four types. Results for trials in children aged 7–12 years have shown similar results.Citation72 However, results from efficacy trials are not yet available to make any recommendations.

Pregnant women

In the USA, approximately 900,000 teenagers become pregnant each year.Citation73 While the HPV vaccine did not appear to affect pregnancy outcomes in Phase III clinical trials negatively, the HPV vaccine has not been approved for pregnant women.Citation74 Additional trials and observations are being conducted to make the recommendations.

Organ transplant patients

Each year in the USA, there are about 2591 transplant candidates younger than 18 years, and about 1892 undergo transplantation.Citation75 Women undergoing organ and bone marrow transplantation tend to be at increased risk for HPV-related genital and oral disease, including cancer.Citation76–Citation78 It seems these patients are also very vulnerable to HPV and infection outcomes. Vaccine trials are underway to assess HPV vaccine efficacy and adverse effects in this vulnerable population, but to date no specific recommendations have been made.

Survivors of childhood cancer

Women surviving childhood cancer are at increased risk of second malignancies. Nevertheless, the relationship between childhood cancer and HPV-related cancer is not known and has not been consistently observed. While the median age for cervical cancer is 47–48 years, most of the female survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort are currently too young to assess for HPV-related complications. However, females receiving specific types of cancer therapy during childhood tend to be vulnerable to HPV-related diseases.Citation79 Ongoing studies are examining vaccination in the childhood cancer survivor population. However, the Children’s Oncology Group’s Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer (version 3.0) recommend HPV vaccination for all eligible females surviving childhood cancer.

Barriers and challenges to vaccination

Current recommendations for the HPV vaccine require a three-dose series, and it is evident from the National Immunization Survey-Teen conducted by the CDC in 2009 that adolescents are not receiving all three doses (44.3% had one dose and 26.7% had all three doses).Citation60 In a large study of 3297 females, Widdice et al reported low overall completion rates, ie, 21.4% in 9–10-year-olds, 19.6% in 11–12-year-olds, 29.6% in 13–18-year-olds, and 30.4% in 9–26-year-olds.Citation80 Currently, race does not seem to make a difference as to whether one receives the first dose of the HPV vaccine. However, African American women tend to have lower rates of three-dose completion than Caucasian females aged 9–26 years.Citation80,Citation81 If racial disparities do exist in vaccine completion rates, this could intensify existing disparities in cervical cancer. One study suggested that vaccine completion in adolescent females also depended on the reasons for clinical visits; higher vaccine completion was observed among those who had a vaccine-only visit versus a nonsick or sick visit.Citation82 This indicates that providing vaccine-specific visits to the clinic along with reminders could increase the uptake.

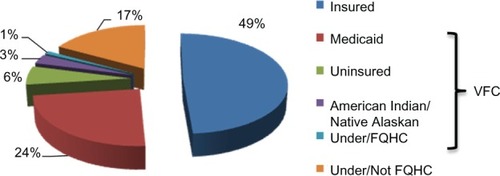

One of the issues regarding adherence to the vaccine schedule, or even starting the HPV vaccine process, is the cost of the vaccine. The cost for a single dose of the HPV vaccine is approximately $130.Citation83 Most health insurance plans cover recommended vaccines such as HPV for the recommended age group. However, the cost is high if it is not covered, especially if it comes as an unexpected medical bill. In the National Immunization Survey-Teen, the majority of adolescents (49%) had insurance, 34% were covered under Vaccines for Children, and 17% were either underinsured or not qualified for Federally Qualified Health Centers ().Citation60 Vaccines for Children is a federally funded program that helps eligible children (those on Medicaid, uninsured, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or underinsured) receive necessary vaccines.Citation84 Adolescent females with private insurance were more likely to complete the HPV vaccine series than those with Medicaid.Citation82 As of January 2011, adolescent males were also eligible for the Vaccines for Children to assist with permissive use of HPV vaccine, as recommended by the ACIP.Citation85 Prior to government assistance, it is possible that vaccination rates in males remained low, and now through Vaccines for Children, vaccination rates in males are expected to increase. However, vaccination rates for males are unlikely to be as high as for females because the vaccine is still recommended only for “permissive use” in males. Even with such encouraging programs to help cover the costs of HPV vaccine, several issues need to be carefully monitored and considered to encourage uptake of the vaccine in adolescent males and females.

Figure 4 Financial sources among adolescents receiving HPV vaccine. Vaccine is mostly covered by individual insurance, Vaccine for Children (VFC) program (those on Medicaid, uninsured, American Indian or Alaskan Native or underinsured), and Federally Qualified Health Centers.

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

Parents

Parent’s perception of the HPV vaccine plays a vital role regarding adherence to and administration of the vaccine. Parents have been found to be influenced by: denial of risk, believing that their child is not currently at risk for HPV because she/he is not sexually active and want to wait until they become sexually active;Citation45 concerns about vaccine safety, feeling the vaccine is “too new” because the HPV vaccine was approved by the FDA less than 10 years ago, and some did not feel they knew enough about the long-term side effects;Citation86 riskier adolescent behaviors, feeling that an STI vaccine could promote sexual promiscuity because the adolescent would feel less at-risk;Citation87,Citation88 reluctance regarding STI immunization and a sexuality discussion with the child, having a difficult time discussing sex with their child, and early childhood vaccination would bring up sex for discussion;Citation89 belief that the child receives too many vaccines, with anxiety about vaccine side effects and the health of their children as a result;Citation88 and concern that health insurance will not cover the vaccine and they will be left with the “unnecessary” bill.Citation86 The majority of the concerns parents have can be avoided with proper education regarding the HPV vaccine. Knowledge of the benefits of the HPV vaccine could help enlighten parents and assist them in making an informed decision. Parent sociodemographic variables, such as ethnicity and religion, are also strongly associated with acceptance of the HPV vaccine.Citation90 HPV awareness is lower among ethnic minority women than among Caucasian women and lower among non-Christian than Christian mothers.Citation90 In a multinational review of parental attitudes about HPV vaccination, there was little difference between parental attitudes about vaccinating their daughters (70%) versus their sons (65%).Citation20,Citation91 The main reason parents refused to vaccinate their sons was that they did not believe their child would benefit directly from the HPV vaccine.Citation20

Health care providers

Physicians’ and health care providers’ recommendations for the HPV vaccine are likely to influence parents’ and adolescents’ decisions regarding vaccination. A physician’s attitude toward vaccination has been shown to be influenced by professional characteristics, office procedures, and vaccine cost and reimbursement.Citation45 Physicians and parents prefer the vaccination of older adolescent males and females,Citation20,Citation86,Citation92 leaving out the most vulnerable and recommended younger adolescents. This is likely due to the HPV vaccine being a STI vaccine, because parents and physicians possibly feel older adolescents have a greater need for the vaccine. When it comes to choosing a vaccine for males, physicians in general prefer a vaccine that protects against both genital warts and cervical cancer as opposed to a vaccine that is known to protect only against cervical cancer.Citation20

Vaccinees

HPV vaccine acceptance is also dependent on adolescents’ opinions of the vaccine. Adolescents’ knowledge of HPV appears to be influenced by physicians and health educators, peer groups, and media.Citation45 Adolescents’ acceptance of STI vaccines is generally high and has been found to be influenced positively by perception of vaccine characteristics, health benefits, provider recommendations, increased perceived susceptibility to STIs, and perceived benefit of immunization. On the other hand, adolescents’ negative reactions are due mostly to vaccine causing infection, low perception of risk, and fear of needles.Citation45 Adolescents’ acceptance of the vaccine is high, but the actual rates of initiation and completion of the HPV vaccine are low. In a study of college-aged males, 34% would accept a vaccine that protected against cervical cancer alone, while 78% would accept a vaccine that protected against both cervical cancer and genital warts.Citation93 Again, there is greater acceptance of male vaccination when there is a direct benefit to the person being vaccinated.

Safety

The safety of both HPV vaccines is continually monitored by the CDC and the FDA via three reporting systems that can track adverse events known to be associated with vaccines as well as detect rare adverse events that may not have been identified by the relevant clinical trials. Safety information based on clinical trials for both vaccines is listed in . Post-licensing safety information from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System reported that, as of February 14, 2011, there have been a total of 18,354 adverse events following Gardasil vaccination and 26 adverse event reports following Cervarix vaccination in the USA.Citation58 Since the FDA licensure of Gardasil for males in 2009, there have been 205 Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System reports, of which 15 were serious adverse events.Citation58 The vast majority of these reports in females were considered nonserious (92% for Gardasil and 96% for Cervarix), defined by the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System as adverse events other than hospitalization, death, permanent disability, or life-threatening illness.Citation58

School

Successful vaccine programs require vaccination for school entry, ensuring that all students are protected before entering school. However, HPV vaccine will not be required for middle-school entry in any state anytime in the near future.Citation94 The state mandates for HPV vaccine are discussed among legislators each year and have failed to pass thus far. For example, Texas governor, Rick Perry, issued an executive order in early February 2007 requiring HPV vaccine for girls upon entry into middle school.Citation94 However, controversial political agendas overruled, overshadowing the public health benefit. In New Hampshire and South Dakota, while the vaccine was not mandated, the governors provide the vaccine at no cost to girls under 18 years.Citation94 Likewise, Washington’s legislature approved spending $10 million to vaccinate 94,000 girls voluntarily in the next 2 years.Citation94 As indicated in and , the uptake of the HPV vaccine is more evident in such states where cost is subsidized or minimized by the government. While mandatory vaccination for children in each state allows parents to opt out of vaccine requirements due to medical, moral, or religious opposition,Citation95 only 11% of Caucasian parents supported HPV vaccine mandates compared with 78% of African-American parents and 90% of Latino parents.Citation96

Conclusion

Although Gardasil and Cervarix are effective against selected HPV infections and associated cervical precancers, there are several challenges to the delivery and uptake of the vaccine. Both vaccines are prophylactic and do not eliminate existing infections, so regular Pap screening is still necessary for the care and treatment of those already infected. Also the vaccines do not cover all HPV types, and currently, cross-strain protection against other oncogenic strains has not been shown. Total longevity of protection against HPV from the vaccine is not known. However, to date, immunogenicity has been sustained for up to 6.4 years. This follow-up time is not adequate to assess the effect on cancer because it takes 20–25 years to develop the disease. In addition, uptake of the vaccines is challenged by the high cost, feasibility, and logistics of three dose deliveries. The biggest impact on acceptability of the vaccine comes from adolescents, physicians, parents, and the community. Disparity in HPV vaccine uptake also exists by geographical area, income status, risk of cervical cancer, and HPV-related malignancies, gender, and race, as evident from the national study in the USA. Until these shortcomings are addressed and everyone from parents and physicians to community leaders are involved in the program, vaccine uptake efforts cannot be fully successful, especially in adolescents. New methods and technology that might involve adolescents regularly, including social networking websites, text-messaging, e-mails and other Web-based tools should be considered and utilized to educate and increase the uptake of HPV vaccine. HPV uptake and availability globally are beyond the scope of this review, but the challenges and issues should be carefully compared with those observed in the USA to assess and implement optimal uptake among the most vulnerable individuals around the world.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BoschFXManosMMMunozNPrevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study GroupJ Natl Cancer Inst199587117968027791229

- MarcellAAdolescenceKliegmanRMBehrmanREJensonHBStantonBFNelson Textbook of Pediatrics18th edPhiladelphia, PASaunders Elsevier2007

- WinerRLLeeSKHughesJPGenital human papillomavirus infection: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university studentsAm J Epidemiol2003157321822612543621

- AbmaJCMartinezGMMosherWDDawsonBSTeenagers in the United States: sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2002. National Center for Health StatisticsVital Health Stat20042324148

- EatonDKKannLKinchenSYouth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2005Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ20065551108

- WeinstockHBermanSCatesWJrSexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000Perspect Sex Reprod Health200436161014982671

- BartholomewDAHuman papillomavirus infection in adolescents: a rational approachAdolesc Med Clin200415356959515625994

- FisherMRosenfeldWDBurkRDCervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in suburban adolescents and young adultsJ Pediatr199111958218251658285

- MoscickiABPalefskyJGonzalesJSchoolnikGKHuman papillomavirus infection in sexually active adolescent females: prevalence and risk factorsPediatr Res19902855075132175024

- FerreccioCPradoRBLuzoroAVPopulation-based prevalence and age distribution of human papillomavirus among women in Santiago, ChileCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200413122271227615598792

- ShermanMESchiffmanMCoxJTEffects of age and human papilloma viral load on colposcopy triage: data from the randomized Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance/Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion Triage Study (ALTS)J Natl Cancer Inst200294210210711792748

- BrownDRShewMLQadadriBA longitudinal study of genital human papillomavirus infection in a cohort of closely followed adolescent womenJ Infect Dis2005191218219215609227

- MoscickiABGenital HPV infections in children and adolescentsObstet Gynecol Clin North Am19962336756978869952

- StanleyMHPV – immune response to infection and vaccinationInfect Agent Cancer201051920961432

- WalboomersJMJacobsMVManosMMHuman papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwideJ Pathol19991891121910451482

- SchiffmanMHCastlePEpidemiologic studies of a necessary causal risk factor: human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasiaJ Natl Cancer Inst2003956E212644550

- BoschFXLorinczAMunozNMeijerCJShahKVThe causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancerJ Clin Pathol200255424426511919208

- BoschFXEpidemiology of human papillomavirus infections: new options for cervical cancer preventionSalud Publica Mex200345SupplS326S339 Spanish14746025

- BoschFXde SanjoseSHuman papillomavirus in cervical cancerCurr Oncol Rep20024217518311822990

- LiddonNHoodJWynnBAMarkowitzLEAcceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine for males: a review of the literatureJ Adolesc Health201046211312320113917

- KjaerSKTranTNSparenPThe burden of genital warts: A study of nearly 70,000 women from the general female population in the 4 Nordic countriesJ Infect Dis2007196101447145418008222

- PallecarosAVonauBHuman papilloma virus vaccine – more than a vaccineCurr Opin Obstet Gynecol200719654154618007131

- US Food and Drug AdministrationApproval letter: human papillomavirus quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, 18) vaccine, recombinant682006 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBlood-Vaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm111283.htmAccessed May 28, 2011

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA approves new vaccine for prevention of cervical cancer10162009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm187048.htmAccessed February 16, 2011

- US Prescribing Information for GARDASIL® updated; Indication not granted for use in adult women462011 Available from: http://www.merck.com/newsroom/news-release-archive/vaccine-news/2011_0406.htmlAccessed May 28, 2011

- GarlandSMHernandez-AvilaMWheelerCMQuadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseasesN Engl J Med2007356191928194317494926

- PaavonenJNaudPSalmeronJEfficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young womenLancet2009374968630131419586656

- RomanowskiBde BorbaPCNaudPSSustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial up to 6.4 yearsLancet200937497061975198519962185

- GiulianoARPalefskyJMGoldstoneSEfficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in malesN Engl J Med2011364540141121288094

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA approves new indication for gardasil to prevent genital warts in men and boys10162009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm187003.htmAccessed May 28, 2011

- VillaLLAultKAGiulianoARImmunologic responses following administration of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus Types 6, 11, 16, and 18Vaccine20062427–285571558316753240

- BlockSLNolanTSattlerCComparison of the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in male and female adolescents and young adult womenPediatrics200611852135214517079588

- KoutskyLEpidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infectionAm J Med19971025A389217656

- Clinicaltrials.govUS NLoM. Identifier NCT01077856, Vaccine Impact in Population Study (VIP)2006 Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01077856Accessed May 30, 2011

- LeeYCNewportMJGoetghebuerTInfluence of genetic and environmental factors on the immunogenicity of Hib vaccine in Gambian twinsVaccine200624255335534016701924

- NewportMJGoetghebuerTWeissHAGenetic regulation of immune responses to vaccines in early lifeGenes Immun20045212212914737096

- NewportMJGoetghebuerTMarchantAHunting for immune response regulatory genes: vaccination studies in infant twinsExpert Rev Vaccines20054573974616221074

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2010592063063220508594

- Barnholtz-SloanJPatelNRollisonDIncidence trends of invasive cervical cancer in the United States by combined race and ethnicityCancer Causes Control20092071129113819253025

- Committee on Adolescent Health CareACOG Committee Opinion No. 436: evaluation and management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology in adolescentsObstet Gynecol200911361422142519461460

- SafaeianMSolomonDCastlePECervical cancer prevention – cervical screening: science in evolutionObstet Gynecol Clin North Am200734473976018061867

- United States Cancer StatisticsDepartment of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta (GA), and National Cancer Institute: U S Cancer Statistics Working GroupUnited States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report2010 Available from: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/Accessed June 21, 2011

- NandaKMcCroryDCMyersERAccuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: a systematic reviewAnn Intern Med20001321081081910819705

- AdamsMJasaniBFianderAHuman papilloma virus (HPV) prophylactic vaccination: challenges for public health and implications for screeningVaccine200725163007301317292517

- GambleHLKloskyJLParraGRRandolphMEFactors influencing familial decision-making regarding human papillomavirus vaccinationJ Pediatr Psychol201035770471519966315

- InsingaRPDasbachEJElbashaEHAssessing the annual economic burden of preventing and treating anogenital human papillomavirus-related disease in the USA: analytic framework and review of the literaturePharmacoeconomics200523111107112216277547

- ArmstrongEPProphylaxis of cervical cancer and related cervical disease: a review of the cost-effectiveness of vaccination against oncogenic HPV typesJ Manag Care Pharm201016321723020331326

- TechakehakijWFeldmanRDCost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination compared with Pap smear screening on a national scale: a literature reviewVaccine200826496258626518835313

- PartridgeJMHughesJPFengQGenital human papillomavirus infection in men: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of university studentsJ Infect Dis200719681128113617955430

- GiulianoARLuBNielsonCMAge-specific prevalence, incidence, and duration of human papillomavirus infections in a cohort of 290 US menJ Infect Dis2008198682783518657037

- GiulianoARLeeJHFulpWIncidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort studyLancet2011377976993294021367446

- DunneEFNielsonCMStoneKMMarkowitzLEGiulianoARPrevalence of HPV infection among men: a systematic review of the literatureJ Infect Dis200619481044105716991079

- HullSCCaplanALThe case for vaccinating boys against human papillomavirusPublic Health Genomics2009125–636236719684448

- TairaAVNeukermansCPSandersGDEvaluating human papillomavirus vaccination programsEmerg Infect Dis200410111915192315550200

- ElbashaEHDasbachEJInsingaRPModel for assessing human papillomavirus vaccination strategiesEmerg Infect Dis2007131284117370513

- KimJJGoldieSJCost effectiveness analysis of including boys in a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in the United StatesBMJ2009339b388419815582

- BrissonMVan de VeldeNBoilyMCEconomic evaluation of human papillomavirus vaccination in developed countriesPublic Health Genomics2009125–634335119684446

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionReports of health concerns following HPV vaccination2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/vaccines/hpv/gardasil.htmlAccessed May 19, 2011

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2009 Adult vaccination coverage, NHIS2009 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nhis/2009-nhis.htmAccessed June 21, 2011

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years – United States, 2009MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201059321018102320724968

- BachPBGardasil: From bench, to bedside, to blunderLancet2010375971996396420304226

- American Cancer SocietyCancer Facts and Figures 2010Atlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society2010

- D’SouzaGAgrawalYHalpernJBodisonSGillisonMLOral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infectionJ Infect Dis200919991263126919320589

- LuBViscidiRPLeeJHHuman papillomavirus (HPV) 6, 11, 16, and 18 seroprevalence is associated with sexual practice and age: results from the Multinational HPV Infection in Men study (HIM study)Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev2011205990100221378268

- PalefskyJMHuman papillomavirus-related disease in men: not just a women’s issueJ Adolesc Health2010464 SupplS12S1920307839

- ChiaoEYGiordanoTPPalefskyJMTyringSEl SeragHScreening HIV-infected individuals for anal cancer precursor lesions: a systematic reviewClin Infect Dis200643222323316779751

- KimJJTargeted human papillomavirus vaccination of men who have sex with men in the USA: A cost-effectiveness modelling analysisLancet Infect Dis2010101284585221051295

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionHIV/AIDS among youth2008 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/youth.htmAccessed May 7, 2011

- FrischMBiggarRJGoedertJJHuman papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndromeJ Natl Cancer Inst200092181500151010995805

- [No authors listed]1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adultsMMWR Recomm Rep199241RR-17119

- WilkinTLeeJYLensingSYSafety and immunogenicity of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in HIV-1-infected menJ Infect Dis201020281246125320812850

- LevinMJMoscickiABSongLYSafety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine in HIV-infected children 7 to 12 years oldJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201055219720420574412

- KleinJDAdolescent pregnancy: Current trends and issuesPediatrics2005116128128615995071

- GarlandSMAultKAGallSAPregnancy and infant outcomes in the clinical trials of a human papillomavirus type 6/11/16/18 vaccine: a combined analysis of five randomized controlled trialsObstet Gynecol200911461179118819935017

- SweetSCWongHHWebberSAPediatric transplantation in the United States,1995–2004Am J Transplant200665 Pt 21132115216613592

- MaloufMAHopkinsPMSingletonLSexual health issues after lung transplantation: Importance of cervical screeningJ Heart Lung Transplant200423789489715261186

- RoseBWilkinsDLiWHuman papillomavirus in the oral cavity of patients with and without renal transplantationTransplantation200682457057316926603

- SeshadriLGeorgeSSVasudevanBKrishnaSCervical intraepithelial neoplasia and human papilloma virus infection in renal transplant recipientsIndian J Cancer2001382–4929512593446

- KloskyJLGambleHLSpuntSLHuman papillomavirus vaccination in survivors of childhood cancerCancer2009115245627563619813272

- WiddiceLEBernsteinDILeonardACMarsoloKAKahnJAAdherence to the HPV vaccine dosing intervals and factors associated with completion of 3 dosesPediatrics20111271778421149425

- StokleySUpdate: HPV Vaccination Coverage Among US Adolescent FemalesPresented at the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices MeetingAtlanta, GAOctober 2010 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-oct10/08-03-hpv-Female.pdfAccessed June 21, 2011

- NeubrandTPBreitkopfCRRuppRBreitkopfDRosenthalSLFactors associated with completion of the human papillomavirus vaccine seriesClin Pediatr2009489966969

- American Cancer SocietyHow much does the HPV vaccine cost? Is it covered by health insurance plans?2011 Available from: http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CancerCauses/OtherCarcinogens/InfectiousAgents/HPV/HumanPapillomaVirusandHPVVaccinesFAQ/hpv-faq-vaccine-costAccessed February 8, 2011

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionVaccines for children program2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/default.htmAccessed May 3, 2011

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionFDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)2010 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5920a5.htm?s_cid=mm5920a5_eAccessed May 2, 2011

- DaleyMFCraneLAMarkowitzLEHuman papillomavirus vaccination practices: A survey of US physicians 18 months after licensurePediatrics2010126342543320679306

- DaleyMFLiddonNCraneLAA national survey of pediatrician knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus vaccinationPediatrics200611862280228917142510

- KahnJAZimetGDBernsteinDIPediatricians’ intention to administer human papillomavirus vaccine: The role of practice characteristics, knowledge, and attitudesJ Adolesc Health200537650251016310128

- KahnJARosenthalSLTissotAMFactors influencing pediatricians’ intention to recommend human papillomavirus vaccinesAmbul Pediatr20077536737317870645

- MarlowLAWardleJForsterASWallerJEthnic differences in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccine acceptabilityJ Epidemiol Community Health200963121010101519762455

- ZimetGDRosenthalSLHPV vaccine and males: Issues and challengesGynecol Oncol20101172 SupplS26S3120129653

- DempseyAFAbrahamLMDaltonVRuffinMUnderstanding the reasons why mothers do or do not have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against human papillomavirusAnn Epidemiol200919853153819394865

- JonesMCookRIntent to receive an HPV vaccine among university men and women and implications for vaccine administrationJ Am Coll Health2008571233218682342

- National Conference of State LegislaturesHPV Vaccine: State Legislation 2009–2010 Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/IssuesResearch/Health/HPVVaccineStateLegislation/tabid/14381/Default.aspxAccessed May 2, 2011

- OmerSBPanWKHalseyNANonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements: secular trends and association of state policies with pertussis incidenceJAMA2006296141757176317032989

- PerkinsRBPierre-JosephNMarquezCIlokaSClarkJAParents’ opinions of mandatory human papillomavirus vaccination: does ethnicity matter?Womens Health Issues201020642042621051001

- ParkinDMBrayFChapter 2: the burden of HPV-related cancersVaccine200624 Suppl 3S11S25

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2009 NIS-Teen Vaccination Coverage Table Data2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nisteen/data/tables_2009.htmAccessed June 21, 2011

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescent aged 13–17 years – United States, 2008MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep20095836997100119763075

- American Cancer SocietyGlobal Cancer Facts and Figures 2008Atlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society2011

- World Health OrganizationHuman papillomavirus and related cancers in World WHO/ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer (HPV Information Centre)2010 Available from: http://www.who.int/hpvcentre/en/Accessed June 21, 2011

- US Food and Drug AdministrationProduct approval prescribing information [Package insert]Gardasil [human papillomavirus quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine, recombinant]Whitehouse Station, NJMerck and Co, Inc2009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm1123.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- US Food and Drug AdministrationProduct approval prescribing information [package insert]Cervarix [human papillomavirus bivalent (types 16 and 18) vaccine, recombinant]GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals2009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/biologics-bloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm186957.htmAccessed May 19, 2011

- Advisory Committee of Immunization PracticesNational Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunizationMMWR Recomm Rep2011602164

- US Food and Drug AdministrationApproval letter: human papillomavirus bivalent (types 16,18) vaccine, recombinant10162009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm186959.htmAccessed May 8, 2011