Abstract

A woman’s age at menarche (first menstrual period) and her age at menopause are the alpha and omega of her reproductive years. The timing of these milestones is critical for a woman’s health trajectory over her lifespan, as they are indicators of ovarian function and aging. Both early and late timing of either event are associated with risk for adverse health and psychosocial outcomes. Thus, the search for a relationship between age at menarche and menopause has consequences for chronic disease prevention and implications for public health. This article is a review of evidence from the fields of developmental biology, epidemiology, nutrition, demography, sociology, and psychology that examine the menarche–menopause connection. Trends in ages at menarche and menopause worldwide and in subpopulations are presented; however, challenges exist in constructing trends. Among 36 studies that examine the association between the two sentinel events, ten reported a significant direct association, two an inverse association, and the remainder had null findings. Multiple factors, including hormonal and environmental exposures, socioeconomic status, and stress throughout the life course are hypothesized to influence the tempo of growth, including body size and height, development, menarche, menopause, and the aging process in women. The complexity of these factors and the pathways related to their effects on each sentinel event complicate evaluation of the relationship between menarche and menopause. Limitations of past investigations are discussed, including lack of comparability of socioeconomic status indicators and biomarker use across studies, while minority group differences have received scant attention. Suggestions for future directions are proposed. As research across endocrinology, epidemiology, and the social sciences becomes more integrated, the confluence of perspectives will yield a richer understanding of the influences on the tempo of a woman’s reproductive life cycle as well as accelerate progress toward more sophisticated preventive strategies for chronic disease.

Introduction

In 2010, 62 million women of childbearing age (ie, 15–44 years) were reported in the United States.Citation1 An estimated 6000 American women aged 40 to 59 years reach menopause daily with a minimum of another 20 years of life expectancy.Citation2 The age at menopause marks the final step in ovarian aging, while the age at menarche indicates the onset of the female reproductive cycle; however, the life course of oocytes begins in utero.Citation3 The interval between the age at menarche and age at menopause is the length of a woman’s reproductive years and this is associated with risk for chronic disease and life expectancy as well as having implications for population structure and dynamics. Understanding whether there is a relationship between age at menarche and age at menopause, the magnitude and direction of this relationship, and the factors influencing the relationship might lead to preventive strategies for chronic disease and improvement in quality of life.

Menarche is the event signaling the onset of the female reproductive cycle. Mounting evidence has established the significance of menarche as both a footprint for chronic disease risk and compass for health and developmental trajectory. Adverse effects from an earlier age at menarche include risk for premature death, breast, and endometrial cancers ().Citation4–Citation7 The risk for these cancers is partially a function of the number of ovulatory cycles, the length of each cycle, and person-years of menstrual cycles that contribute to the cumulative exposure of breast cells to endogenous steroid hormones like estrogens over the life course.Citation7 Earlier age at menarche is associated with risk for depression, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and metabolic syndrome (including overweight/obesity), insulin resistance, and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Poorer school performance and health risk behaviors such as early age of smoking initiation, early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy have been linked with earlier menarche.Citation6,Citation8–Citation15 A recent meta-analysis indicated a small increased risk for endometriosis with early menarche.Citation16 Within the context of the family, early age at menarche is associated with familial conflict, alterations in family structure, stressful home circumstances, and paternal absence in childhood.Citation17–Citation20 Experiencing abuse in early life may have consequences for the timing of menarche. Sexual abuse has a consistent, but physical abuse has an inconsistent, association with early menarche.Citation21–Citation30 In contrast, late age at menarche is associated with depression and lower bone mineral density (BMD).Citation12,Citation31–Citation33 Exposure to war or postwar conditions has been associated with late menarche.Citation34,Citation35 Socioeconomic factors and psychosocial stressors have been linked to timing of menarche, but the nature of these associations differs.Citation14,Citation18,Citation19,Citation36,Citation37 Poverty in early childhood is related to a decline in the age at menarche among non-Hispanic white (NHW), but not non-Hispanic black (NHB), girls.Citation36,Citation38 The reasons for an earlier age at menarche in NHB versus NHW girls are the subject of intense investigation into the complex interplay between obesity, biological-genetic, and epigenetic plus endocrine processes and cumulative exposures to disadvantageous environments.Citation38

Table 1 Behavioral and health risks attributed to early or late timing of reproductive events

“Menopause” is the permanent cessation of ovulation and menses – that is, the final menstrual period confirmed by the subsequent 12 consecutive months without a menstrual period.Citation39,Citation40 It signifies the loss of reproductive capacity and the exact age of menopause is a marker for aging and health. Early age at menopause is associated with increased risk for CVD and coronary disease, lower BMD, and osteoporosis.Citation41–Citation43 In a meta-analysis of menopause and CVD, early menopause (ie, at younger than 50 years) was associated with a 25% increased risk of CVD after adjustment for smoking in eleven studies and for age at menarche in two of a total of twelve studies.Citation43 Yet, the timing of menarche is essential because a woman who experiences early menarche is at higher risk for early initiation of smoking, which is in turn a risk factor for early menopause. For women with this chronological profile, smoking would be on the causal pathway between menarche, menopause, and CVD whereas women without this profile would not have smoking classified as an intermediate variable. This thus illustrates how the chronology of events determines the treatment of covariates in models. Early menopause plus a short number of reproductive years (ie, the interval between the two events) are associated with risk for low BMD.Citation41,Citation44 Cigarette smoking is related to early menopause, shorter reproductive years, and low BMD, yet few studies have addressed these covariates in the same models. Late age at “natural” menopause (ie, self-reported absence of menses for 12 consecutive months not due to radiation, hysterectomy, or drug use) is associated with risk for breast and endometrial cancers but a greater life expectancy and reduced all-cause mortality.Citation7,Citation45 The inverse association between age at menopause and all-cause mortality confers only a 1.6% reduction in risk per 3-year increase in age at menopause after adjustment for age at menarche, body mass index (BMI), and parity.Citation4 In addition to health effects from the age at each sentinel event, the interval between the two events – the number of reproductive years – has implications for health; notably, a short interval due to late menarche and early menopause is associated with risks for CVD, metabolic disorders, low BMD, and fractures, while a long interval due to an early menarche and late menopause is related to risk for hormonal cancers ().Citation46,Citation47

Table 2 Duration of reproductive years associated with health risks

Menopause occurs naturally in most women; however, it may result from a bilateral oophorectomy, referred to as “surgical menopause,” or be chemically induced by cancer treatment. Under either condition, the age at induced menopause has implications for risk of chronic disease (other than the cancer associated with chemical treatments), aging, and quality of life. Hormone therapy can also alter the course of and disease risk associated with age at menopause. Further, women who undergo natural menopause within a period that closely matches the tendency of their age cohort may misreport their age at menopause (ie, introduce recall bias), which may lead to error in the generation of the “true” statistical presence of this event.Citation48 Thus, it is challenging to identify trends in and the percentage of women who experience natural menopause in a modern population.

An understanding of the relationship between the ages at menarche and menopause may lead to an exploration of underlying mechanisms related to follicular atresia, fertility, and disease across the life course. Yet, the area under the curve for all girls who experience menarche for the first time in a year does not predict which of them will experience ovulatory cycles and be fertile or which women will experience a natural, chemical, or surgical menopause from among all women of reproductive age.

This paper is written from the perspective of our two fields – life-course epidemiology and demography. The objectives of this article are to (1) describe follicular development and aging and trends in the age at menarche and menopause; (2) review the state of the science of the association between the two sentinel events, the factors linking ages at menarche, and menopause; and (3) offer recommendations for future research.

What do we know?

Ovarian development in utero and the maintenance of primordial oocytes throughout childhood are essential for ovulation and reproduction. During fetal development, there are 6–7 million primordial follicles, most of which undergo apoptosis (cell death) that peaks in the midtrimester of pregnancy before the female baby is delivered.Citation49 After birth, follicles must remain in the primordial state for several years with support from the surrounding environment. Many do not become or remain arrested but initiate growth or undergo apoptosis in prepubertal life, so fewer survive until menarche. Importantly, the surviving oocytes constitute a nonrenewable pool that partially determines the reproductive capacity of the woman.Citation49,Citation50 With increasing reproductive years, decreasing numbers of follicles coincide with diminished oocyte quality and dictate gradual changes in menstrual cycle regularity and monthly fecundity (number of children born per woman). The rate of oocyte decline accelerates from approximately 38 years onward and the rate of follicle loss increases as women age. The estimated numbers of oocytes are: 1–2 million at birth, 300,000–400,000 by menarche, ≥400 during reproductive years that reach the ovulatory stage, and <1000 at menopause.Citation50,Citation51 The factors influencing selective survival of oocytes over the life course are unclear and are hypothesized to include: genetic variants in, for example, Bcl-2 and Bax; epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation and histone modifications; accumulated damage to oocytes over the life course from smoking and other exogenous factors; parity; chronic inflammatory states like obesity; and age-related changes in the quality of the granulosa cells surrounding the follicles and in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis.Citation49,Citation52,Citation53 In summary, the rate of follicular atresia over the life course differs by developmental stage, but the factors influencing follicular cell death or, conversely, evolutionary conservation of follicles require further exploration.

Menarche is the event that signifies the onset of oocyte functioning, and its variability in timing is evident from the range in age at menarche across and within populations.Citation54,Citation55 It is now known that the menstrual cycle is under genetic and epigenetic regulation in tandem with the HPA axis.Citation52,Citation53 Meta-analyses of large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified about 50 candidate genes for the trait, some of which differ by ethnicity. Most GWAS, however, are based on research in NHW.Citation56,Citation57 With each menstrual cycle, the endometrium undergoes cyclic changes in morphology and function involving growth, differentiation, and regression.Citation58 Communication between the HPA and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axes, the cyclic epigenetic alterations and expression of genes, and biosystemic conditions such as obesity and metabolic disease determine female fecundity, influence ovarian aging, and have implications for long-term survival.Citation53,Citation59 Maternal age at menarche and daughters’ age at menarche are positively correlated, but the magnitude of the correlation has decreased over time.Citation60,Citation61 The decline in the mother–daughter correlation points to the growing importance of environmental factors or gene– environment interactions.Citation62,Citation63 Ethnic-group variation in the declining age at menarche is another marker for the potential effect of environmental influences.Citation64,Citation65 Thus, a myriad set of factors including genes, epigenetic alterations, and endogenous and exogenous environmental exposures interact cumulatively over the life course and have implications for trends in the age at menarche.

Menopause is the final step in the process of ovarian aging. Biomarkers of ovarian aging include age-related levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), anti-Müllerian hormone, and inhibins A and B. Cycle irregularity is an indicator of the menopausal transition, as illustrated by frequency of lengthened cycles or missed periods, while the perimenopause includes the year following the final menstrual bleed.Citation51 The menopausal transition occurs on average at 46 years with a range from 34–54 years, while the average age of menopause is 51 years with a range from 40–60 years.Citation51 The large variation in menopausal age represents the variability in ovarian aging.Citation51 Yet, underlying causes of subfertility do not predispose a woman to an earlier age at menopause.Citation66 Thus, the life course of follicles begins in utero, with unknown survival mechanisms to menarche, followed by repetitive cyclic follicle recruitment, single dominant follicle selection, ovulation, the formation of a corpus luteum, leading either to fertilization and implantation or regression, endometrial shedding, and menses, and ends with age-related increase in follicular atresia until menopause.

Maternal age at menopause and daughters’ age at menopause are correlated, but the magnitude is not as high as the correlation for menarche. Secular trends in use of hormonal preparations for menopausal symptoms that delay or limit the ability to detect the age at menopause might reduce the true correlation. Other covariates that might affect the relationship include: the obesity epidemic and cohort-specific exposures to cigarette smoking by the woman and in her environment. Estimates of the heritability factor range from 44%–72% for menarche and 44%–63% for menopause.Citation67–Citation70 Recent GWAS of age at menarche and at natural menopause have been conducted primarily in NHW women, with a replication of the NHW loci in Hispanic women; several genes are associated with the length of reproductive years.Citation71,Citation72 All results so far explain a small proportion of the variation in the age at menarche and at menopause. Future explorations may require large sample sizes to examine gene–environment interactions such as the interaction between alcohol, smoking, parity, and length of breast-feeding with variants of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene on the timing of menarche and menopause.Citation73

Trends in age at menarche

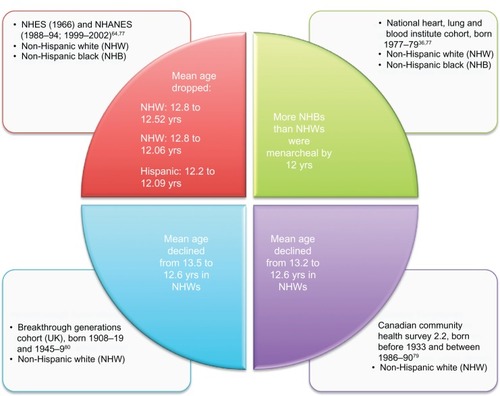

For decades, the average age at menarche has declined in populations across Europe, North America, and other economically wealthy regions, but recent evidence indicates the trend has begun to stabilize for certain, not all, ethnic groups.Citation74 The research has largely been conducted among NHW girls, with more recent data from Hispanic and NHB populations.Citation64,Citation65,Citation75,Citation76 Most trends are based on cross-sectional surveys in the USA, Canada, and Britain. Based on data from the US National Health Interview Survey of 1966 and National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys of 1988–1994 and 1999–2002, the mean age at menarche declined from 12.80 to 12.57 to 12.52 and from 12.90 to 12.09 to 12.06 years in NHWs and NHBs, respectively (). These trends for NHWs and NHBs reflect a decline followed by a leveling off of the average age at menarche. In contrast, the average age at menarche in Hispanics declined from 12.20 to 12.09 years from 1988–1994 to 1999–2002.Citation64,Citation77 The New York Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP) of girls born in 1959–1966 did not detect a difference in the ethnic group-specific mean age at menarche, whereas, a more recent National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute cohort study of girls born 1977–1979 reported more NHB girls had reached menarche by age 12 than NHW.Citation36,Citation37 A higher BMI was consistently associated with earlier age at menarche in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys of 1988–1994 to 1999–2002 across ethnicities.Citation77,Citation78 Analysis of data from a largely NHW Canadian population indicated the mean age of menarche declined from 13.2 years for those born before 1933 to 12.6 years for those born 1986–1990.Citation79 In the same survey, a 1-year increase in age at menarche was associated with a decrease in mean BMI of approximately 0.5 kg/m2. The average age at menarche in a large British cohort declined from 13.5 years among NHW women born 1908–1919 to 12.6 years among women born 1945–1949.Citation80

Trends in age at menopause

Beginning with the work of Sanes in 1918, researchers have reported trends in the age at menopause at international, national, and local levels but consistently dwell on caveats that limit the ability to detect a trend.Citation81–Citation83 For example, the World Health Organization reported an average age at menopause in the 1990s of 51 years in industrialized countries.Citation39 Based on interviews from 1979–1988 in eleven countries, the median age of 2949 of 18,997 women who experienced natural menopause ranged from 49 to 51 years, with a lower limit of 40 years. Of note, participants were hospitalized for non-gynecologic or non-obstetric reasons and were controls compared with cases in a study of female cancers.Citation55 Study of a 1946 British birth cohort revealed that the cohort had a mean age of 50.5 years and a median of 50 years and 11 months but only 695 of 2547 women experienced natural menopause according to the data analysis.Citation84,Citation85 Among 444 American women born 1908–1922 who reported menstrual histories from the 1930s to the 1970s, the median age at menopause was 50.5 years, with 75% reaching menopause by 52.4 years and 95% by 54.7 years.Citation86

Timing of menopause among racial and/or ethnic groups has not been well documented. One of the largest sources is the Multiethnic Cohort Study of 95,000 women aged 45–74 years in 1993–1996, who are being followed to date.Citation87 Race/Ethnicity was strongly associated with age at natural menopause independent of smoking, age at menarche, parity, and BMI. Notably, compared to NHWs, natural menopause occurred earlier in both US- and non-US-born Latinas, later among Japanese-Americans, but did not differ among NHBs and NHWs. In an analysis of factors influencing entry into stages of the menopausal transition, NHB women entered the transition earlier than NHW women, but race was not associated with entry into late transition stages.Citation88 Also, women with higher estradiol levels entered the transition earlier than those with lower levels. This mimics the cyclic fluctuation of estradiol according to race, whereby NHBs have higher estradiol levels than NHWs.Citation88,Citation89

Trends in the age at menopause were reported in a pooled analysis of female controls aged ≥ 60 born 1910–1969 from three population-based case-control studies in the USA. The average age at natural menopause for those born 1910–1914 was 49.9 years. In subsequent 5-year birth cohorts (1915–1919, 1920–1924, 1925–1929, 1930–1934, and 1935–1939), the mean age at menopause was 49.1, 49.5, 50.1, and 50.5 years. A 17-month increase was observed in the mean age for those born 1915–1939 (mean 49.9 vs 50.5 years [P = 0.0001]) after adjustment for state of residence, smoking, education, parity, age at last birth, height, and BMI.Citation90 For women in this study born between 1911–1925, women in the 1911–1915 cohort had earlier ages at menopause than women born in later years within that time span (P = 0.002).Citation91 These women were participants in a breast cancer screening project, but the menopause study was restricted to women who never took oral contraceptives, were married, had at least one child, and were screened in 1984. The kappa for reliability for age at natural menopause was reported in two studies to be 0.82 and 0.88.Citation90,Citation91 In a 1989 cross-sectional study of Finnish women, the mean age of menopause was 51.7 years, while earlier Finnish data revealed means of 47.9 in 1897, 48.4 in 1915, 48.5 in 1921, and 49.8 in 1961. These data were not tested for significance in trend.Citation92 A highly significant positive trend in age at natural menopause was reported in Swedish women born 1908–1930 with interviews in 2000–2002.Citation93 Based on two prospective cohort studies in nine European countries, data were collected on age at menopause (ie, the date of the final menstruation); FSH, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol concentrations confirmed self-reported menopausal status in a sub-cohort. The age at natural menopause increased with increasing birth year, yet, there was significant heterogeneity across the countries, indicating country-specific factors influencing the differences in age at menopause.Citation94 Illustrative population-based studies that did not detect a trend in the age at menopause include Kaczmarek’s in Poland,Citation95 Burch and Gunz’s in New Zealand,Citation96 and Stadel and Weiss’ in the USA.Citation97

Establishing a trend in the age at menopause is challenging due to small sample sizes, a selective or nonrepresentative population sources, and inconsistent definitions for menopause across studies that range from self-definition to use of biomarkers plus reported absence of menses for 12 consecutive months. Interestingly, two studies that examined whether inclusion of women with surgical menopause altered the age-specific trend in menopause did not find any effect from their inclusion in the trend analysis.Citation98,Citation99 Other issues include: limited use of biomarkers such as FSH levels to confirm menopausal status and use of censored data when subsets of a cohort, but not all members, had experienced menopause. Data may be biased if recalled by elderly women or by women hospitalized under unfavorable circumstances. Moreover, the test of trend period ranged from a few years to over 100 years.Citation96

Association of age at menarche with age at menopause

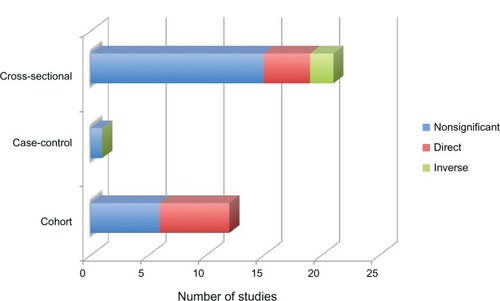

In a review of studies with a sample size of ≥100 participants, no consistent association between age at menarche and age at menopause was observed ( and ). Only 12 of 36 studies reported a significant association, with six of these cross-sectional surveys and six cohort studies.Citation87,Citation93–Citation95,Citation100–Citation107 All six cohort studies reported a direct association between the age at menarche and menopause.Citation87,Citation93,Citation94,Citation102,Citation103,Citation106 Of note, only two had prospectively collected data, although one of theseCitation103 analyzed age at regular, not first, menses.Citation93,Citation103 Of the other four cohort studies, three had censored data setsCitation87,Citation94,Citation102; and three analyzed baseline data.Citation87,Citation94,Citation106 Only those who would have experienced an early menopause, and therefore the direct correlation of early menarche and early menopause would more likely appear.Citation102 In a study of Chinese women born 1930–1960, the direct association appeared between late menarche (ie, mean age of menarche of 15.2 years, with 70% reaching menarche at ≥14 years) and late menopause (ie, mean age of 49.2 years). This Chinese cohort had unique environmental exposures and cultural practices that influenced their short number of reproductive years.Citation106 In contrast, another eight cohort studies had null findings but did not identify whether menarche and menopause occurred early or late.Citation88,Citation91,Citation115,Citation121,Citation122,Citation125–Citation127 Of the six cross-sectional studies, four reported direct associationsCitation95,Citation101,Citation104,Citation105 and two an inverse association.Citation100,Citation107 In contrast, 15 cross-sectional studies reported null findings.Citation48,Citation69,Citation109–Citation114,Citation116–Citation120,Citation123,Citation124 The majority of the studies enrolled NHW and/or Asian women. A more recent investigation extended the null findings in a population of NHB women in the USA after adjustment for parity, years of oral contraceptive use, and smoking status.Citation125 Sammel et al did not observe a relationship between age at menarche and age at entry into the menopausal transition in a population-based biracial cohort.Citation88 The primary interest in their study was in testing reproductive hormone levels as predictors of menopausal stage; to that end, age at menarche was grouped with other covariates in the models. Gold, in a review of evidence spanning several decades, sums it up adequately in stating that age at menarche is “fairly consistently” not associated with age at menopause, especially after adjustment for other reproductive variables.Citation45

Figure 2 Association between ages at menarche and menopause by numbers of studies, design, and significance.

Table 3 Association between the age at menarche and age at natural menopause

The search for the association between the ages at menarche and menopause is complex. It is important to recognize that the life course of primordial follicles begins in utero and these follicles must remain at rest within a nurturing environment from birth until menarche. Subsequent reproductive years require endogenous supportive mechanisms dependent on epigenetic, genetic, and environmental factors that may work in combination but are largely unknown. The timing and types of exposures that lead to iterations in age at menarche, menstrual cycle patterns, fecundity, ovarian aging, and age at menopause are not clearly delineated. Acute exposures, as experienced by the diethylstilbestrol (DES) cohort and the offspring of the Dutch famine of 1944, provide clues to windows of susceptibility in utero to ovarian function.Citation128–Citation130 Thus, the absence of an association may not reflect the underlying biological reality because follicular atresia in the face of an exogenous insult like DES may be an alternative to survival. Several phenomena might mask the association, including: surgical menopause that truncates the age at menopause for health reasons, like breast cancer, for which age at menarche is a recognized risk factor; use of hormonal preparations such as oral contraceptives to induce ovulation and regulate menstrual cycles; epidemics of obesity that are associated with a decline in the age at puberty, in fecundity, and menopause; exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors; and ethnic variation in pubertal development and in the cyclic fluctuation of hormones that arise from interactions between environmental, genetic, and epigenetic phenomena.Citation131,Citation132 All of these factors as well as unknown factors underlying the biological process of follicular atresia over the life course may hamper the detection of an association.

Exposures across the life course influencing menarche and menopause

Hormonal exposures

Over the life course, exposures to environmental and hormonal factors during the prenatal, postnatal, and adolescent periods have the potential to initiate, promote, and/or alter mammary and ovarian changes that may affect both age at menarche and natural menopause.Citation133–Citation136 The effects of in utero exposures to environmental endocrine disruptors in pregnancy and maternal factors during pregnancy have been reported in several studies.Citation137–Citation142 During the critical phases of fetal development, these exposures, as illustrated following, can affect the hormonal milieu, triggering changes in the programming of the HPA axis that could result in adverse birth outcomes and subsequent changes in reproductive development.Citation133,Citation135,Citation143,Citation144 For instance, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and low birth weight are associated with lower levels of leptin and adiponectin at birth.Citation145 These hormones play key roles in regulating reproductive functions throughout the life cycle. From childhood until the onset of pubertal development, levels of leptin gradually increase with a concurrent decrease in adiponectin.Citation146,Citation147 It is believed that leptin’s role in the initiation of reproductive development is permissive: a critical level of leptin may be needed to activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis and subsequently maintain reproductive function.Citation148 The regulating roles of leptin and adiponectin are somewhat complementary; however, faster weight gain in infancy as well as obesity and/or other metabolic disturbances during adolescence and adulthood can disrupt this regulation process.

Women exposed to DES in utero have a slightly increased risk of earlier age at menarche than those unexposed; a dose– response effect has been observed.Citation137 Similar findings have been reported for age at natural menopause: women exposed to DES were more likely to start menopause almost a year before the unexposed.Citation128,Citation138 These findings are consistent with early programming of biological factors controlling age at menarche and menopause.Citation149–Citation151

Weight gain in pregnancy, birth weight, and growth

During pregnancy, greater maternal weight gain, lack of physical activity, and gestational diabetes are associated with earlier menarche in girls who are the offspring of these pregnancies and limited studies have reported a slightly earlier menopause among women exposed to similar conditions in utero.Citation14,Citation138,Citation141,Citation142,Citation152 Birth weight, length at birth, and Ponderal Index (a measure of obesity in newborns) have been inconsistently associated with timing of menarche and menopause.Citation141,Citation153–Citation159 Several studies have reported an inverse relationship between birth weight and age at, or hormonal markers of, menarche, while others found little to no association.Citation141,Citation153–Citation156,Citation158,Citation159 Other findings suggest that low birth weight followed by accelerated growth has a greater impact on age at menarche than birth weight alone; however, the effects of the timing of postnatal growth on the relationship between birth weight and age at menarche are not consistent across studies.Citation137,Citation141,Citation159–Citation164 Ong et al have reported that accelerated growth during the first 2 years of life plays a crucial role in subsequent weight gain and pubertal development, while others suggest that weight gain or BMI above the fiftieth percentile at different stages in childhood, rather than infancy, has the greatest impact on age at menarche.Citation162,Citation164–Citation166 Most studies have reported little to no association between birth weight and age at menopause except for Tom et al, who found a U-shaped association, with women of low (<2 kg) or high (≥4 kg) birth weight experiencing an earlier natural menopause than those weighing 3.00–3.49 kg at birth.Citation136,Citation138,Citation157,Citation167 Findings for postnatal growth and age at menopause remain scarce; one study reported a slight inverse association with weight at 2 years,Citation168 while another reported an earlier menopause among women with low weight at 1 year.Citation136 The relationship between prenatal exposure, birth weight, and age at menarche is thought to be related to altered functioning of the HPA axis, while lower age at menopause may be due to reduction in the initial size of the follicular cohort or follicular atresia. Ibáñez et al reported that women who experienced growth restriction in utero or were born with an extremely low birth weight had a reduction in ovarian and uterine size in neonatal life and in adolescence, but no data have been reported for age at menopause.Citation169–Citation171

Few studies are adequately powered to assess the moderating effect of postnatal nutrition and subsequent growth on the relationship between birth weight and age at menarche or natural menopause.Citation158,Citation172 Nevertheless, the predictive adaptive response paradigm presents a framework that explains the interplay of a nutrient-restricted environment followed by a nutrient-rich environment.Citation173 This paradigm stipulates that a fetus is able to predict the quality of the postnatal environment based on the environment in utero. When the predicted and actual exposures do not match, the child will exhibit adverse phenotypes that may result in increased risk of subsequent disease. For instance, growth-restricted infants born into a nutrient-rich environment tend to experience a faster rate of growth during infancy.Citation165,Citation174,Citation175 Catch-up growth in early infancy is associated with increased risk of childhood obesity, which may be responsible for triggering early pubertal development and subsequent age at menarche.Citation176,Citation177

Breast-feeding

Findings suggest that the tempo of growth during infancy can potentially be mitigated by breast-feeding, which is thought to prevent or delay the tempo of growth during this period.Citation158,Citation162,Citation178–Citation180 Two recent studiesCitation141,Citation180 reported evidence suggesting a positive association between breast-feeding and age at menarche, while othersCitation158 have not. Al-Sahab et alCitation180 reported a 6% reduction in age at menarche for each additional month of exclusive breast-feeding in a Filipino population, while Morris et alCitation141 found a significant increase in age at menarche among British girls who were breast-fed compared with those who were formula-fed. Although a few studies have reported an earlier age at menopause among women who were ever breast-fed or breast-fed for >7 months, the long-term protective effect of breast-feeding remains largely unknown.Citation138,Citation157,Citation163 Methodological challenges from differential assessment of breast-feeding across studies, temporal ordering of the exposure–outcome relationship, and adjustment of time-varying covariates during the life course make it difficult to assess the long-term protection conferred by breast-feeding.Citation181

Body mass/obesity

A 2005–2006 World Health Organization cross-national health behavior survey across 29 countries had a standardized questionnaire administered to 15,783 15-year-old girls about age at menarche, weight, height, and socioeconomic status (SES), the latter of which used a validated summary index based on the number of cars and computers owned, family holidays per year, and whether one’s bedroom was shared.Citation182 Age at menarche was inversely associated with BMI and directly associated with individual-level family affluence after adjustment for a cluster sampling design and country prevalence of overweight. In the USA, however, the relationship between SES and overweight for girls is race specific: in NHWs there are similar SES gradients in overweight and age at menarche, but, in NHW girls, there is an inverse social gradient in overweight but no relationship between SES and menarche.Citation38 Across multiple studies, obesity or overweight is positively associated with age at menopause, with comparable cut-offs for BMI.Citation69,Citation84,Citation87,Citation93,Citation100,Citation122,Citation151,Citation183 These studies largely rely on BMI measurements proximal to the endpoint rather than on reported data. Two studies reported null findings: Sammel et alCitation88 found no association between BMI and entry into menopausal transition, while van Noord et alCitation91 reported no association with age at natural menopause.

Cigarette smoking and secondhand smoke exposure

Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke prenatally and during early childhood and timing of menarche are not consistently associated due to bias from maternal recall, the data source (ie, data abstracted from prenatal records compared with questionnaire-based information), and competing birth cohort exposures to environmental contaminants like DDT.Citation184–Citation186 For example, reports from the CPP study of women pregnant in 1959–1966 consistently demonstrate a direct association between exposure to tobacco smoke in utero and in childhood and later age at menarche.Citation184,Citation186 In contrast, women in the California Child Health and Development Study (CHDS) who smoked during pregnancy (1959–1966) had daughters at higher risk for early menarche.Citation185 All pregnant women in the CHDS were exposed to DDT but those exposed before 14 years of age were at higher risk for breast cancer and their daughters may be at potential risk for early menarche from environmental endocrine exposures. Note that the CPP data were abstracted from prenatal records or based on maternal recall whereas the CHDS imputed childhood smoke exposure of the daughter from maternal reporting of prenatal smoke exposure. In utero exposure to cigarette smoking was associated with early age at menopause only among female offspring who never smoked, while the inverse association between adult cigarette smoking and menopause has been consistently demonstrated.Citation88,Citation91,Citation98,Citation104,Citation187–Citation189

SES, menarche, and menopause

Socioeconomic development is consistently pointed to for its role in the decline in age of menarche over the twentieth century. It is noteworthy that the decline in age of menarche has paralleled long-term increases in adult height and childhood body size, but recent evidence indicates the uncoupling of the age at menarche and adult height as obesity has become an important determinant of menarche.Citation62,Citation190,Citation191 Together, these patterns of early life growth and development point to the increased control individuals gained over their bodies as well as over their environment through much of the twentieth century.Citation192

In modern populations, an individual’s control over her body and her environment is rooted in her access to resources that garner health advantage. Individuals’ access to these resources stems from their relations with each other and their position in a society’s economic and social structures, described here as “socioeconomic status.”Citation193 Traditional markers of SES include education, occupation, income and wealth, as well as markers that are sensitive to an individual’s resources that may differ over the life course (eg, the SES characteristics of one’s parents during childhood compared with one’s own SES as an adult).Citation194 Although the associations between SES and health outcomes are often remarkably stable over time and across societies, causal mechanisms can be highly variable, as stratification systems, public policies, available technologies and the like shape the specific pathways by which resources are translated into health advantages. Thus, although consistency might be expected in the associations between SES and the timing of menarche and menopause – say in the USA and European countries – it is difficult to infer this given societal differences in childhood health, obesity, smoking, and environmental exposures to contaminants related to menarche and/or menopause.

Research by life-course epidemiologists highlights the complex ways in which SES resources over the life course potentially influence the association between the timing of menarche and menopause.Citation163,Citation168,Citation195,Citation196 Although an exhaustive review of this general approach is beyond the scope of this paper, several key points are highly pertinent for understanding this association. First, SES early in life may set in motion a cascading set of events that ultimately link menarche with menopause. For example, childhood poverty may lower the age of menarche, which in turn increases the risk of early pregnancy, disrupts adult achievement, and eventually increases the risk of early menopause. Thus, understanding life-course pathways is likely to be fundamentally important in understanding the relationship between the timing of menarche and menopause. Second, menarche and menopause may be associated because SES is a common factor influencing both events. For example, SES disadvantages in childhood may lead to an earlier age at menarche and adult SES disadvantages may lead to an earlier age at menopause. Given the high correlation between early life SES and adult SES, correlated environments may thus make it appear that the timing of menarche is associated with the timing of menopause. Third, the timing of socioeconomic advantages and disadvantages in the life course may play a very important role in understanding the association between menarche and menopause. For example, a plausible hypothesis is that early life SES alters the timing of menarche, which then sets in motion the pace of a biological process that determines the timing of menopause. All of these issues highlight the critical importance of a fully fleshed conceptual model that articulates how exposures and pathways potentially connect the timing of menarche and menopause.

At the outset, it is important to note that few studies in the USA or Europe have explicitly examined how the timing of menarche and menopause are simultaneously associated with SES. Typically, studies examine one or the other endpoint of a woman’s reproductive stage as a consequence of SES, although a few studies examining menopause control for age of menarche when assessing earlier life influences.Citation4,Citation94,Citation128,Citation196

Recent research in the USA suggests that the age of menarche is postponed, on average, for persons who are socio economically advantaged, although these effects appear to be sensitive both to the measurement of SES and the consistency of effects across race/ethnic groups.Citation36,Citation37 Braithwaite et al, for example, reported for three geographically diverse clinic-based samples (the National Growth and Health Study) that NHW girls in families with low household income (measured at age 9) reported earlier ages of menarche, although the opposite association was reported for NHB girls.Citation36 No relationship was found between parental education and the timing of menarche, suggesting that the association is sensitive to the SES marker.Citation36 In 2010, James-Todd et al drew on the New York site of the CPP to assess how an SES index was associated with the timing of menarche.Citation37 In contrast to the study by Braithwaite et al, James-Todd et al measured SES at birth and again at age 7, allowing them to assess how changes in SES, as well as SES at different ages, were associated with menarche. Their results suggest that the SES at age 7 has a stronger effect on menarche than the SES at birth when adjusted for race/ethnicity, mother’s age at menarche, mother’s place of birth, and father’s absence from the home at birth. In addition, they reported that a decline in SES between birth and age 7 accelerated the onset of menses.

These studies, although offering some intriguing results, are beset with limitations that challenge our understanding of the association between SES and the timing of menarche. Neither study, for example, used a population-based, random sample that would yield a nationally representative sample. This sample-design problem is shared by other studies on this topic that are based on data from other countries.Citation163 Sample-design issues present a serious challenge to extrapolating to both the US population and to race/ethnic groups. In addition, it is evident that significant attention is needed in understanding how alternative metrics of SES are associated with menarche, how different measures might operate differentially across major demographic groups, and how SES at different points in a person’s life – as well as changes in SES – may alter the timing of menarche. A key point based on these studies is that it is unclear how SES is associated with menarche at the population level, which challenges our ability to assess how SES is related to the link between the timing of menarche and menopause.

Studies of the association between SES and the timing of menopause have generally found that menopausal age increases with SES.Citation91–Citation93,Citation95,Citation98,Citation99,Citation113,Citation197–Citation199 A number of studies examining the effects of adult SES on age of menopause have taken into account age of menarche.Citation92,Citation93,Citation197 These studies have typically reported that the association between age of menopause and adult SES is robust when controlling for age of menarche and confounders such as BMI. Associations between specific markers of SES and age of menopause appear to be sensitive to controls for other markers of SES as well as the population where the study was conducted. For example, Luoto et al observed in a representative sample of Finnish women aged 45–64 years that both education and adult occupational status were associated with a later age of menopause independent of each other.Citation92 Rödström et al observed a similar pattern in a prospective population study of Swedish women, although education’s net association with age of menopause was not significant when occupation was controlled.Citation93 It is unclear whether the variability in the effects of SES on age of menopause reflects differences in measurement approaches or differences in the health resources conferred by education and occupation across populations.

Life-course epidemiological studies have examined the associations between SES and menopause, although these studies typically have not controlled for the age of menarche.Citation188,Citation195,Citation196 The general theoretical motivation is that early life and later-life conditions may alter the structure and function of reproductive capacity that ultimately influences the age of menopause. Lawlor et al documented that women more advantaged socioeconomically in early and adult life experienced a later age of menopause.Citation196 Both early and late-life socioeconomic positions exerted independent effects, and socioeconomic resources combined throughout the life course in an additive fashion to influence the timing of menopause. The effects of early life conditions were somewhat attenuated by leg length, pointing to developmental growth as a possible mechanism linking early life with menopause. Adult BMI and smoking played an important role in explaining the association of adult SES with age of menopause.

Otero et al discovered similar relationships between early and late-life SES (measured by eleven and five indicators, respectively) and age at menopause in a prospective cohort study of Brazilian university employees. Women with a shorter trunk length or less schooling had small, but significant, risk of early menopause. However, statistical analyses did not control for early life SES on later-life socioeconomic variables, nor was an analytical construct created to represent the effect of additive socioeconomic factors on menopause outcome.Citation188

In contrast to Lawlor et al’s study, Hardy and Kuh did not find evidence that early and adult resources combined additively to influence menopause.Citation195 Instead, they showed that the effects of early life socioeconomic resources exerted the strongest influence on menopause relative to adult resources and that early life SES effects were robust to controls for later-life SES and behavioral risk factors associated with menopause (eg, BMI and smoking). This pattern is consistent with the idea that early life resources alter the rate of follicular atresia, although whether this occurs only in early life or across the entire life course is unclear.

The answer to this question is important for understanding the role that socioeconomic resources play in linking the age of menarche with the age of menopause. Moreover, because socioeconomic resources typically confer more proximate resources, risks, and rewards such as those concerning smoking, psychological stressors, growth, and BMI, SES may operate through a variety of pathways over the life course. As yet, these pathways remain largely ambiguous.

Psychosocial factors, menarche, and menopause

A number of researchers have posited that the timing of menarche and/or menopause is sensitive to psychological stress. In the case of menarche, psychological stress has been hypothesized to accelerate the onset of menarche as a reproductive “strategy.”Citation200–Citation202 High levels of risk or uncertainty in childhood are thought to accelerate reproductive development (ie, menarche) toward a first birth. With regard to menopause, childhood stress has been hypothesized to accelerate the age of menopause because of a higher rate of follicular atresia.Citation85,Citation195 It is unclear whether follicular atresia occurs relatively close to the time of childhood stress or whether childhood stress potentially alters later-life stress responses that may then influence atresia. Another possible pathway between stress experienced in adulthood and follicular atresia is the modulation of the rate of cellular aging by stressors.Citation203 It should be noted that considerable ambiguity surrounds the specific biological mechanisms involved in the associations between childhood and adult psychological stress and the timing of menopause.

The origin of psychological stress in childhood can be conceptualized within the framework of parental socio-emotional involvement with children. Draper and Harpending, for example, argued that girls born into matrifocal households are more interested in and engage in sex at younger ages and are less interested in finding a male who will invest in her and her offspring compared with girls reared in homes with the father present.Citation200 From an evolutionary perspective, girls reared under these conditions are responding to a stressful environment by engaging in behaviors and developing reproductively at a faster rate to maximize reproductive success.Citation200

Belsky et al expanded on this idea, arguing that girls raised in households with marital conflict, absent fathers, and economic insecurity face stressors that undercut strong attachments with their parents and accelerate reproductive strategies and development.Citation201 In contrast, childrearing strategies and patterns that enhance enduring attachment between parents and children provide the context for girls to mature later, engage in sex at later ages, and seek a partner for long-term investments.Citation201 Empirical research generally supports the idea that household stressors such as paternal absence are associated with earlier menarche.Citation17,Citation204–Citation209 Most of these studies were based on small and/or purposive samples. The exception is Belsky et al’s analysis of National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Study of Early Child and Youth Development, which showed that having an insecure attachment during infancy almost doubled a girl’s odds of completing puberty before 13.5 years, net of factors such as maternal age of menarche.Citation207 In another study of a population-based cohort of Mexican-origin residents in Houston Texas, paternal absence was associated with earlier menarche after adjustment for SES, maternal age at menarche, and the girl’s BMI.Citation208 The drawbacks of existing studies are inadequate characterization of the family and household (eg, no distinction between father absence and presence of stepfather) and the aforementioned lack of power due to small sample size.Citation209,Citation210

Research on the age of first sexual intercourse and teenage pregnancy in children raised with or without the biological father provides support for these socio-emotional attachment theories: an earlier age at first sexual intercourse and increased rates of teenage pregnancy are observed in children from households lacking the biological father.Citation211,Citation212 However, age at menarche was not assessed as either a covariate or an outcome in these studies, which limits the applicability of the evidence from behavioral research to the search for biological pathways between father absence and early menarche. Of note, one investigation found that gene–environment interactions complicated the association between father absence and earlier instance of first sexual intercourse; yet, age at menarche was not included in analyses.Citation210 Furthermore, it is unclear whether factors unrelated to socio-emotional attachment influence the association between father absence and early menarche. Learned behavior from a parent who models sexual attitudes and activity may facilitate earlier involvement in sexual activity for girls and this could coincide with an underlying genetic factor that conveys heritability of age at menarche and predisposes to earlier age of sexual intercourse.Citation60,Citation210,Citation213,Citation214 Lastly, the endocrinological profile associated with early pubertal development in girls may interact with the neurological and physical changes of adolescence to affect behavior or sensitivity to the environment, leading to the observed association between early menarche and early initiation of sexual behavior.Citation15,Citation20,Citation215,Citation216 The methodological limitations cited curtail the ability to draw robust conclusions about the effect of socio-emotional attachment on girls’ tempo of development, though the trend is promising for future investigations.

Although the influence of psychological stress on the timing of menopause is thought to work through cellular aging, few studies have examined this issue and most of the evidence is indirect. For example, Epel et al examined how cellular aging – indexed by oxidative stress, telomerase activity, and telomere length – was associated with perceived stress and chronic stress among healthy premenopausal women.Citation203 The highest levels of perceived and chronic stress, determined by a questionnaire and subjects’ caregiver status, respectively, were associated with shortened telomeres and higher oxidative stress. This study is unique in its assessment of these associations in vivo. Evidence from other studies that used either telomere length or telomerase activity as a marker of chronic disease risk supports a link between stress related to obesity and/or SES.Citation217,Citation218 A recent study provides additional support for the effect of adult stress on ovarian reserve, and therefore timing of menopause. Antral follicle count, a marker of ovarian reserve that normally decreases with age, was accelerated in women who scored lower on the positive affect subscale of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, indicating low positive emotion. Lack of positive emotion is observed frequently in depression and is directly related to poor disease prognosis and risk of all-cause mortality.Citation219 Taken together, an association between depression and ovarian aging presents the potential for psychological stress to play a role in the timing of menopause.Citation219,Citation220 Work on this topic is still in its infancy. Translation of the research from clinically depressed populations described here to women categorized by Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale scores is one challenging aspect of this work.Citation221 Furthermore, age at menarche is inconsistently evaluated as a confounding factor in studies of psychological stress exposures that may hasten menopausal onset.Citation219,Citation220

Life-course studies support the idea that psychological stress has important consequences for menopause. Divorce disrupts family life and structure and is viewed as a strong risk factor for stress in children of the divorcing parties.Citation222 Indeed, children of divorced parents have impaired psychological, social, and academic functioning compared with their peers in intact families.Citation223 Divorce had an even stronger association with longevity prediction than childhood socioeconomic position in one study.Citation224 Women from a 1946 British birth cohort study whose parents divorced during the girls’ early childhood (eg, when they were <5 years old) had earlier menopause than those from intact families.Citation195 However, caution must be taken not to overlook the effect on children’s stress level of marital conflict between parties that remain married. Divorce, if it results in a more positive atmosphere and reduces children’s exposure to marital conflict, may be less harmful to children’s health than a fractious marriage.Citation225–Citation227 Investigation into putative biological and social pathways that underlie the association between divorce-related stress and menopause in particular, and childhood stress and health outcomes in general, is warranted.

Future directions

A paradox appears in the observation of no relationship between age at menarche and menopause in the presence of associations of SES, BMI, and race/ethnicity with each event. SES and BMI are dynamic characteristics of the life course but little has been done to create comparability in assessment and depiction of their trajectory across studies. Race/Ethnicity is a multi-pronged marker of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental forces that appear to potentially modulate SES and BMI effects. Thoughtful examination of exposures are essential to an understanding of potential critical periods or windows of susceptibility as one size will not necessarily fit all. Attention has been directed to genetic variants associated with menarche, as reflected in over 40 papers on the subject since 2003. Likewise, a similar pattern appears in GWAS in menopause and in genes in common to menarche and menopause. Yet, the time trend in age at menarche demonstrates dramatic variation by ethnicity over brief periods, with SES, breast-feeding, and obesity as potential explanations for the disparities.

While methodological limitations to research will forever plague the field, relatively recent developments in endocrinology and population science may lead the way. Biro et al’s landmark research in pathways to puberty underscores the assessment of age at entry into pubarche and thelarche as being independent of each other and in tandem with diverse hormonal constellations in girls who enter one stage earlier than the other.Citation228–Citation230 At the other end of the spectrum, the workshop on stages of menopausal transition concomitant with an evaluation of hormonal biomarkers of each stage has the potential to direct research to earlier ages in women before cessation of menses.Citation231,Citation232 Indeed, it appears that women with regular menstrual cycles already experience hormone changes that lead to menopause. Thus, the events of menarche and menopause are no longer the pinnacles and we must turn to landmarks currently less distinct that require research to identify sensitive biomarkers to multiple pathways to ovarian aging.

In summary, to understand the constellation of factors related to ages at menarche and menopause, an approach is needed that is generated by birth cohort-dependent life-course pathways related to SES and other environmental exposures interacting with a woman’s physiology.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- US Census Bureau2010 census of population and housing [collection of documents]Washington DCUS Census Bureau2012 Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/Accessed July 19, 2012

- SchmidtPThe 2012 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause SocietyMenopause201219325727122367731

- SkinnerMKRegulation of primordial follicle assembly and developmentHum Reprod Update200511546147116006439

- JacobsenBKHeuchIKvaleGAge at natural menopause and all-cause mortality: a 37-year follow-up of 19,731 Norwegian womenAm J Epidemiol20031571092392912746245

- HamiltonASMackTMPuberty and genetic susceptibility to breast cancer in a case-control study in twinsN Engl J Med2003348232313232212788995

- GolubMSCollmanGWFosterPMPublic health implications of altered puberty timingPediatrics2008121Suppl 3S218S23018245514

- ParkinDM15. Cancers attributable to reproductive factors in the UK in 2010Br J Cancer2011105Suppl 2S73S7622158326

- SticeEPresnellKBearmanSKRelation of early menarche to depression, eating disorders, substance abuse, and comorbid psychopathology among adolescent girlsDev Psychol200137560861911552757

- RemsbergKEDemerathEWSchubertCMChumleaWCSunSSSiervogelRMEarly menarche and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescent girls: the Fels Longitudinal StudyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059052718272415728207

- FrontiniMGSrinivasanSRBerensonGSLongitudinal changes in risk variables underlying metabolic Syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood in female subjects with a history of early menarche: the Bogalusa Heart StudyInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200327111398140414574352

- JohanssonTRitzénEMVery long-term follow-up of girls with early and late menarcheEndocr Dev2005812613615722621

- GraberJASeeleyJRBrooks-GunnJLewinsohnPMIs pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthoodJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443671872615167088

- IbáñezLPotauNde ZegherFRecognition of a new association: reduced fetal growth, precocious pubarche, hyperinsulinism and ovarian dysfunctionAnn Endocrinol (Paris)2000612141142

- Boynton-JarrettRRich-EdwardsJFredmanLGestational weight gain and daughter’s age at menarcheJ Womens Health (Larchmt)20112081193120021711153

- MendleJTurkheimerEEmeryREDetrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girlsDev Rev200727215117120740062

- NnoahamKEWebsterPKumbangJKennedySHZondervanKTIs early age at menarche a risk factor for endometriosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studiesFertil Steril2012983702712. e622728052

- MoffittTECaspiABelskyJSilvaPAChildhood experience and the onset of menarche: a test of a sociobiological modelChild Dev199263147581551329

- BogaertAFAge at puberty and father absence in a national probability sampleJ Adolesc200528454154616022888

- EllisBJEssexMJFamily environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: a longitudinal test of a life history modelChild Dev20077861799181717988322

- EllisBJTiming of pubertal maturation in girls: an integrated life history approachPsychol Bull2004130692095815535743

- Herman-GiddensMESandlerADFriedmanNESexual precocity in girls. An association with sexual abuse?Am J Dis Child198814244314333348186

- RomansSEMartinJMGendallKHerbisonGPAge of menarche: the role of some psychosocial factorsPsychol Med200333593393912877408

- WiseLAPalmerJRRothmanEFRosenbergLChildhood abuse and early menarche: findings from the Black Women’s Health StudyAm J Public Health200999Suppl 2S460S46619443822

- ZabinLSEmersonMRRowlandDLChildhood sexual abuse and early menarche: the direction of their relationship and its implicationsJ Adolesc Health200536539340015837343

- BrownJCohenPChenHSmailesEJohnsonJGSexual trajectories of abused and neglected youthsJ Dev Behav Pediatr2004252778215083128

- FosterHHaganJBrooks-GunnJGrowing up fast: stress exposure and subjective “weathering” in emerging adulthoodJ Health Soc Behav200849216217718649500

- TurnerPKRuntzMGGalambosNLSexual abuse, pubertal timing, and subjective age in adolescent girls: A research noteJ Reprod Infant Psycol1999172111118

- MendleJLeveLDVan RyzinMNatsuakiMNGeXAssociations Between Early Life Stress, Child Maltreatment, and Pubertal Development Among Girls in Foster CareJ Res Adolesc201121487188022337616

- Boynton-JarrettRWrightRJPutnamFWChildhood abuse and age at menarcheJ Adolesc Health2012 In press. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1054139X12002273

- Boynton-JarrettRHarvilleEWA prospective study of childhood social hardships and age at menarcheAnn Epidemiol2012221073173722959664

- EastellRRole of oestrogen in the regulation of bone turnover at the menarcheJ Endocrinol2005185222323415845915

- FoxKMMagazinerJSherwinRReproductive correlates of bone mass in elderly women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupJ Bone Miner Res1993889019088213252

- TuppurainenMKrögerHSaarikoskiSHonkanenRAlhavaEThe effect of gynecological risk factors on lumbar and femoral bone mineral density in peri- and postmenopausal womenMaturitas19952121371457752951

- PrebegZBralicIChanges in menarcheal age in girls exposed to war conditionsAm J Hum Biol200012450350811534042

- TahirovićHFMenarchal age and the stress of war: an example from BosniaEur J Pediatr1998157129789809877035

- BraithwaiteDMooreDHLustigRHSocioeconomic status in relation to early menarche among black and white girlsCancer Cause Control2009205713720

- James-ToddTTehranifarPRich-EdwardsJTitievskyLTerryMBThe impact of socioeconomic status across early life on age at menarche among a racially diverse population of girlsAnn Epidemiol2010201183684220933190

- ReaganPBSalsberryPJFangMZGardnerWPPajerKAfrican-American/white differences in the age of menarche: accounting for the differenceSoc Sci Med20127571263127022726619

- World Health Organization (WHO)Research on the Menopause in the 1990s: Report of WHO Scientific GroupGenevaWHO1996

- HarlowBLSignorelloLBFactors associated with early menopauseMaturitas20003513910802394

- Kritz-SilversteinDBarrett-ConnorEEarly menopause, number of reproductive years, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal womenAm J Public Health19938379839888328621

- ParazziniFBidoliEFranceschiSMenopause, menstrual and reproductive history, and bone density in northern ItalyJ Epidemiol Community Health19965055195238944857

- AtsmaFBartelinkMLGrobbeeDEvan der SchouwYTPostmenopausal status and early menopause as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysisMenopause200613226527916645540

- Osei-HyiamanDSatoshiTUejiMHidetoTKanoKTiming of menopause, reproductive years, and bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study of postmenopausal Japanese womenAm J Epidemiol199814811105510619850127

- GoldEBThe timing of the age at which natural menopause occursObstet Gynecol Clin North Am201138342544021961711

- Fernández-AlonsoAMCuadrosJLChedrauiPMendozaMCuadrosAMPérez-LópezFRObesity is related to increased menopausal symptoms among Spanish womenMenopause Int201016310511020956684

- LejskováMAlušíkSSuchánekMZecováSPithaJMenopause: clustering of metabolic syndrome components and population changes in insulin resistanceClimacteric2011141839120443721

- McKinlaySJefferysMThompsonBAn investigation of the age at menopauseJ Biosoc Sci19724021611735030375

- HartshorneGMLyrakouSHamodaHOlotoEGhafariFOogenesis and cell death in human prenatal ovaries: what are the criteria for oocyte selection?Mol Hum Reprod2009151280581919584195

- SarrajMADrummondAEMammalian foetal ovarian development: consequences for health and diseaseReproduction2012143215116322106406

- BroekmansFJSoulesMRFauserBCOvarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequencesEndocr Rev200930546549319589949

- MunroSKFarquharCMMitchellMDPonnampalamAPEpigenetic regulation of endometrium during the menstrual cycleMol Hum Reprod201016529731020139117

- PurcellSHMoleyKHThe impact of obesity on egg qualityJ Assist Reprod Gen2011286517524

- Herman-GiddensMERecent data on pubertal milestones in United States children: the secular trend toward earlier developmentInt J Androl2006291241246 discussion 286–29016466545

- MorabiaACostanzaMCInternational variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid ContraceptivesAm J Epidemiol199814812119512059867266

- PerryJRStolkLFranceschiniNMeta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies two loci influencing age at menarcheNat Genet200941664865019448620

- DvornykVWaqar ulHGenetics of age at menarche: a systematic reviewHum Reprod Update201218219821022258758

- YamagataYAsadaHTamuraIDNA methyltransferase expression in the human endometrium: down-regulation by progesterone and estrogenHum Reprod20092451126113219202141

- KuningasMAltmäeSUitterlindenAGHofmanAvan DuijnCMTiemeierHThe relationship between fertility and lifespan in humansAge (Dordr)201133461562221222045

- GraberJABrooks-GunnJWarrenMPThe antecedents of menarcheal age: heredity, family environment, and stressful life eventsChild Dev19956623463597750370

- ErsoyBBalkanCGunayTEgemenAThe factors affecting the relation between the menarcheal age of mother and daughterChild Care Health Dev200531330330815840150

- OngKKAhmedMLDungerDBLessons from large population studies on timing and tempo of puberty (secular trends and relation to body size): the European trendMol Cell Endocrinol2006254255812

- MouritsenAAksglaedeLSørensenKHypothesis: exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals may interfere with timing of pubertyInt J Androl201033234635920487042

- EulingSYHerman-GiddensMELeePAExamination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findingsPediatrics2008121Suppl 3S172S19118245511

- WuTMendolaPBuckGMEthnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994Pediatrics2002110475275712359790

- de BoerEJden TonkelaarIBurgerCWvan LeeuwenFEOMEGA-project groupAre cause of subfertility and in vitro fertilization treatment risk factors for an earlier start of menopause?Menopause200512557858816145312

- van den BergSMBoomsmaDIThe familial clustering of age at menarche in extended twin familiesBehav Genet200737566166717541737

- TowneBCzerwinskiSADemerathEWBlangeroJRocheAFSiervogelRMHeritability of age at menarche in girls from the Fels Longitudinal StudyAm J Phys Anthropol2005128121021915779076

- SniederHMacGregorAJSpectorTDGenes control the cessation of a woman’s reproductive life: a twin study of hysterectomy and age at menopauseJ Clin Endocrinol Metab1998836187518809626112

- van AsseltKMKokHSPearsonPLHeritability of menopausal age in mothers and daughtersFertil Steril20048251348135115533358

- HeCMurabitoJMGenome-wide association studies of age at menarche and age at natural menopauseMol Cell Endocrinol Epub5142012

- ChenCTFernández-RhodesLBrzyskiRGReplication of loci influencing ages at menarche and menopause in Hispanic women: the Women’s Health Initiative SHARe StudyHum Mol Genet20122161419143222131368

- LiuPLuYReckerRRDengHWDvornykVAssociation analyses suggest multiple interaction effects of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms on timing of menarche and natural menopause in white womenMenopause201017118519019593234

- ParentASTeilmannGJuulASkakkebaekNEToppariJBourguignonJPThe timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity: variations around the world, secular trends, and changes after migrationEndocr Rev200324566869314570750

- ChumleaWCSchubertCMRocheAFAge at menarche and racial comparisons in US girlsPediatrics2003111111011312509562

- Herman-GiddensMESloraEJWassermanRCSecondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings networkPediatrics19979945055129093289

- AndersonSEMustAInterpreting the continued decline in the average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 10 years apartJ Pediatr2005147675376016356426

- HimesJHParkKStyneDMenarche and assessment of body mass index in adolescent girlsJ Pediatr2009155339339719559445

- HarrisMAPriorJCKoehoornMAge at menarche in the Canadian population: secular trends and relationship to adulthood BMIJ Adolesc Health200843654855419027642

- MorrisDHJonesMESchoemakerMJAshworthASwerdlowAJSecular trends in age at menarche in women in the UK born 1908–1993: results from the Breakthrough Generations StudyPaediatr Perinat Epidemiol201125439440021649682

- NorrisCThe menopause. An analysis of two hundred casesAm J Obstet191979767781

- FlintMPSecular trends in menopause ageJ Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol199718265729219101

- SanesKThe age of menopause: a statistical studyTrans Sect Obstet Gynecol Abdom Surg Am Med Assoc1918258284

- HardyRMishraGDKuhDBody mass index trajectories and age at menopause in a British birth cohortMaturitas200859430431418406083

- MishraGHardyRKuhDAre the effects of risk factors for timing of menopause modified by age? Results from a British birth cohort studyMenopause200714471772417279060

- WeinsteinMGorrindoTRileyATiming of menopause and patterns of menstrual bleedingAm J Epidemiol2003158878279114561668

- HendersonKDBernsteinLHendersonBKolonelLPikeMCPredictors of the timing of natural menopause in the Multiethnic Cohort StudyAm J Epidemiol2008167111287129418359953

- SammelMDFreemanEWLiuZLinHGuoWFactors that influence entry into stages of the menopausal transitionMenopause20091661218122719512950

- MarshEEShawNDKlingmanKMEstrogen levels are higher across the menstrual cycle in African-American women compared with Caucasian womenJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201196103199320621849524

- NicholsHBTrentham-DietzAHamptonJMFrom menarche to menopause: trends among US Women born from 1912 to 1969Am J Epidemiol2006164101003101116928728

- van NoordPADubasJSDorlandMBoersmaHte VeldeEAge at natural menopause in a population-based screening cohort: the role of menarche, fecundity, and lifestyle factorsFertil Steril1997681951029207591

- LuotoRKaprioJUutelaAAge at natural menopause and sociodemographic status in FinlandAm J Epidemiol1994139164768296776

- RödströmKBengtssonCMilsomILissnerLSundhVBjoürkelundCEvidence for a secular trend in menopausal age: a population study of women in GothenburgMenopause200310653854314627863

- DratvaJGómez RealFSchindlerCIs age at menopause increasing across Europe? Results on age at menopause and determinants from two population-based studiesMenopause200916238539419034049

- KaczmarekMThe timing of natural menopause in Poland and associated factorsMaturitas200757213915317307314

- BurchPRGunzFWThe distribution of the menopausal age in New Zealand. An exploratory studyN Z Med J1967664136105226434

- StadelBVWeissNCharacteristics of menopausal women: a survey of King and Pierce counties in Washington, 1973–2974Am J Epidemiol197510232092161163526

- BrambillaDJMcKinlaySMA prospective study of factors affecting age at menopauseJ Clin Epidemiol19894211103110392809660

- ShinbergDSAn event history analysis of age at last menstrual period: correlates of natural and surgical menopause among midlife Wisconsin womenSoc Sci Med19984610138113969665569

- van KeepPABrandPCLehertPFactors affecting the age at menopauseJ Biosoc Sci Suppl197963755293326

- CramerDWXuHHarlowBLDoes “incessant” ovulation increase risk for early menopause?Am J Obstet Gynecol19951722 Pt 15685737856687

- HardyRKuhDReproductive characteristics and the age at inception of the perimenopause in a British National CohortAm J Epidemiol1999149761262010192308

- NagataCTakatsukaNKawakamiNShimizuHAssociation of diet with the onset of menopause in Japanese womenAm J Epidemiol2000152986386711085398

- OzdemirOCölMThe age at menopause and associated factors at the health center area in Ankara, TurkeyMaturitas200449321121915488349

- ParazziniFDeterminants of age at menopause in women attending menopause clinics in ItalyMaturitas200756328028717069999

- DorjgochooTKallianpurAGaoYTDietary and lifestyle predictors of age at natural menopause and reproductive span in the Shanghai Women’s Health StudyMenopause200815592493318600186

- BouletMJOddensBJLehertPVemerHMVisserAClimacteric and menopause in seven south-east Asian countriesMaturitas19941931571767799822

- BenjaminFThe age of the menarche and of the menopause in white South African women and certain factors influencing these timesS Afr Med J19603431632013798899

- JaszmannLVan LithNDZaatJCThe age of menopause in The Netherlands. The statistical analysis of a surveyInt J Fertil19691421061175786396

- MagurskýVMeskoMSokolíkLAge at the menopause and onset of the climacteric in women of Martin District, Czechoslovkia. Statistical survey and some biological and social correlationsInt J Fertil197520117234380

- BrandPCLehertPHA new way of looking at environmental variables that may affect the age at menopauseMaturitas197812121132755957

- NeriABiderDLidorYOvadiaJMenopausal age in various ethnic groups in IsraelMaturitas1982443413487169966

- StanfordJLHartgePBrintonLAHooverRNBrookmeyerRFactors influencing the age at natural menopauseJ Chronic Dis1987401199510023654908

- OkonofuaFELawalABamgboseJKFeatures of menopause and menopausal age in Nigerian womenInt J Gynaecol Obstet19903143413451969819

- WhelanEASandlerDPMcConnaugheyDRWeinbergCRMenstrual and reproductive characteristics and age at natural menopauseAm J Epidemiol199013146256322316494

- ParazziniFNegriELa VecchiaCReproductive and general lifestyle determinants of age at menopauseMaturitas19921521411491470046

- ChompootweepSTankeyoonMYamaratKPoomsuwanPDusitsinNThe menopausal age and climacteric complaints in Thai women in BangkokMaturitas199317163718412845