Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a chronic, inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. The enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) JIA category describes a clinically heterogeneous group of children including some who have predominately enthesitis, enthesitis and arthritis, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthropathy. ERA accounts for 10%–20% of JIA. Common clinical manifestations of ERA include arthritis, enthesitis, and acute anterior uveitis. Axial disease is also common in children with established ERA. Treatment regimens for ERA, many of them based on adults with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, include the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and biologic agents either individually or in combination.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a chronic, inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. It is the most common pediatric rheumatic illness with an estimated annual incidence of approximately three to six cases per 100,000 children.Citation1 The term “JIA” describes a clinically heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by arthritis that begins before the age of 16 years, involves one or more joints, and lasts at least 6 weeks. Distinct clinical features characterize each of the JIA categories during the first 6 months of the disease. The enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) JIA category describes a clinically heterogeneous group of children including some who have predominately enthesitis, enthesitis and arthritis, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthropathy. ERA accounts for 10%–20% of JIACitation2–Citation4 and mostly occurs in late childhood or adolescence with a peak age of onset of 12 years.Citation5,Citation6 Males are affected more often than females, accounting for approximately 60% of cases.Citation6 Approximately 45% of children are HLA-B27 positive, and 20% have a family history of HLA-B27-associated disease, such as reactive arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or inflammatory bowel disease with sacroiliitis.Citation6 Antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor are characteristically negative.

Diagnosis of ERA

Clinical characteristics of ERA

ERA is defined by the International League Against Rheumatism as arthritis and enthesitis of at least 6 weeks’ duration in a child younger than 16 years, or arthritis or enthesitis plus two of the following: sacroiliac tenderness or inflammatory spinal pain, HLA-B27 positivity, onset of arthritis in a male older than 6 years, and family history of HLA-B27-associated disease.Citation7 Common clinical manifestations of ERA include arthritis, enthesitis, and acute anterior uveitis. In the first 6 months of disease, oligoarticular (in four or fewer joints) disease is most common. The most commonly affected joints at diagnosis are the sacroiliacs, knees, ankles, and hips.Citation6 The small joints of the feet and toes are also commonly involved.Citation8 Midfoot joint inflammation, or tarsitis, is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Axial disease is common in children with established ERA. By 2, 4, and 5 years after disease onset, as many as 15%, 53%, and 92%, respectively, of children with juvenile spondyloarthropathy (SpA), a condition that encompasses most children with ERA, develop symptomatic sacroiliitis.Citation9 Up to 35%–48% of children with ERA have clinical or radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis ().Citation6,Citation10–Citation12 Untreated sacroiliitis may progress to spondylitis, which is a condition characterized by radiographic findings of corner lesions (), erosions, syndesmophytes, diskitis, and ankylosis or fusion of the axial joints. Once sacroiliitis has developed and changes are visible on radiographs, treatment can be problematic. Sacroiliitis may not respond to medications commonly used as first-line agents for JIA, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and the disease may continue to progress along the axial skeleton. A subset of children with sacroiliitis will progress to spondylitis as adults, which is characterized by back pain, stiffness, and eventual fusion of the vertebra.

Figure 1 Radiographic findings of spinal and sacroiliac involvement. (A) Axial T2-weighted image of the sacroiliac joints demonstrate fluid within both sacroiliac joints with widening of the left sacroiliac joint. There is bone marrow edema within the sacral ala and adjacent iliac wings (arrows). (B) Sagittal T2-weighted image of the lumbar spine demonstrates triangular-shaped regions of edema along the corners of the vertebral bodies (arrows) consistent with magnetic resonance corner lesions. (C) Axial T1-weighted postcontrast image shows left hip synovitis (black arrow). There is enhancing edema within both greater trochanters and at the hip flexor entheses (white arrows) with mild surrounding soft tissue inflammatory changes. Courtesy of Dr Nancy Chauvin, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Enthesitis is a distinct pathologic feature of ERA as well as adult SpA, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Enthesitis is defined as inflammation of an enthesis, which is a site where a tendon, ligament, or joint capsule attaches to bone (). Enthesitis in ERA is often symmetric and largely affects the lower limbs.Citation12 In one series, children with ERA had at least one documented tender enthesis at 47% of visits and more than three tender entheses at 18% of visits.Citation6 The most commonly affected entheses were the patellar ligament insertion at the inferior pole of the patella, plantar fascial insertion at the calcaneus, and the Achilles tendon insertion at the calcaneus.Citation6 In another cross-sectional study that used whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to detect enthesitis, the hip extensor insertion at the greater trochanter was the most common site involved.Citation12 Late manifestations of enthesitis in adults include osteopenia, bone cortex irregularity, erosions, soft tissue calcifications, and new bone formation at the bone insertion sites.Citation13,Citation14 Enthesitis may not parallel the activity of, or respond as well to therapy as, the arthritis.Citation15

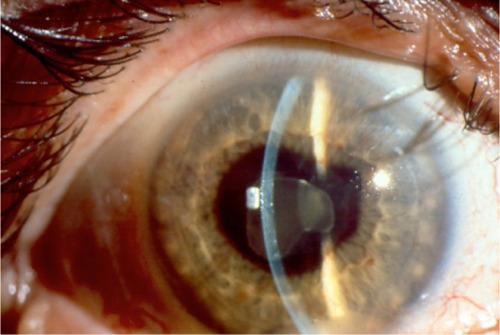

The uveitis associated with ERA is characterized by redness, pain, and photophobia (). It is typically unilateral and often recurrent. In one series, 10% of children developed acute uveitis in the first 6 months of disease.Citation6 Another series reported that 27% of children developed acute anterior uveitis over the course of disease.Citation16 Persistent anterior uveitis can lead to short and long-term complications including iris scarring, corneal calcium deposition, glaucoma, cataracts, macular edema, and visual loss.

Laboratory testing

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for ERA. The selection of specific laboratories should be guided by the history and physical examination. A complete blood count (CBC) with differential and inflammatory markers should be part of the initial evaluation of any child with joint swelling. HLA-B27 is strongly associated with transient reactive arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and ERA. Antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor are typically negative.

Methods to detect enthesitis

Enthesitis in children is typically diagnosed by clinical findings including localized pain, tenderness, and swelling. The findings at certain entheses, however, are nonspecific and can also be found in normal children,Citation17 along with overuse injuries, apophysitis, and fibromyalgia. Multiple instruments have been used in adults to assess the extent and severity of enthesitis in adults, including the Mander Index,Citation18 a modified Mander Index,Citation19 the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada Enthesitis Index,Citation20 the Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score,Citation20,Citation21 the Leeds Enthesitis Index,Citation22 and the Major Enthesitis Index.Citation23 The entheses examined with the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score, Leeds Enthesitis Index, and Major Enthesitis Index are listed in . A standardized enthesitis index for pediatric patients has not yet been developed. In practice, many pediatric rheumatologists examine the lower extremity entheses by applying pressure on each enthesis with the dominant thumb until the nailbed blanches.

Table 1 Entheses included in adult enthesitis indices

Imaging is not routinely used in children for detection of enthesitis. However, in adult SpA, ultrasonography with Doppler (USD) and MRI are helpful to distinguish inflammatory enthesitis from other noninflammatory conditions such as overuse injuries, apophysitis, and fibromyalgia.Citation24–Citation26 The positive and negative predictive values of physical examination for enthesitis at the Achilles tendon in adults, using USD as the gold standard, are 0.55 and 0.73, respectively.Citation24 USD and physical examination may be complimentary, as several studies have shown enthesitis by USD in clinically normal sites.Citation27–Citation29 The most common ultrasound abnor malities in adult entheses are enthesophytes, calcifications, tendon thickening, and hypoechogenicity.Citation27 Imaging with whole-body MRI in children with ERA has suggested that inflammatory enthesitis is overestimated in children by physical examination,Citation12 emphasizing that imaging may be an important tool for assessment of enthesitis and for monitoring treatment response.

Methods to detect sacroiliitis

International League Against Rheumatism criteria define sacroiliitis in children clinically as the presence of tenderness on direct compression over the sacroiliac joint.Citation7 Other physical examination findings that may indicate sacroiliitis are decreased lumbar flexion or a positive Patrick’s test (a maneuver that causes pain in the contralateral sacroiliac joint with downward pressure on the knee when it is flexed and the hip is externally rotated, flexed, and abducted). Inflammatory back pain, which is defined as lower back pain that starts insidiously, improves with exercise, and is associated with more than 30 minutes of morning stiffness or alternating buttock pain, may also herald sacroiliitis.Citation30,Citation31 In one retrospective study, eleven of 53 (21%) children with radiographic findings of sacroiliitis did not have any physical examination abnormalities or a history of inflammatory back pain.Citation32 The positive and negative predictive values of sacroiliac joint compression in the detection of sacroiliitis in children are unknown.

Sacroiliitis is defined by more stringent criteria in adults than in children. In adult studies, the positive and negative predictive values of physical examination to detect sacroiliitis are poor.Citation33,Citation34 As such, the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group and Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria and Amor criteria for axial SpA in adults require the diagnosis of sacroiliitis to be made by imaging with radiographs or MRI. In adults, the gold standard for the early diagnosis of sacroiliitis is MRI with Short TI Inversion Recovery.Citation35–Citation37 Typical findings of sacroiliitis on MRI include bone marrow edema within the sacrum and/or adjacent ilium with or without capsulitis (inflammation of the joint capsule) or enthesitis.Citation35 USD has been proposed as an alternative and less expensive method to evaluate sacroiliitis in adults.Citation38–Citation40 USD is operator-dependent, however, and lacks sufficient resolution and penetration depth to adequately and reliably visualize the sacroiliac joints.Citation41 Whole-body MRI has also been proposed as an alternative method to evaluate the axial skeleton in adults with early disease.Citation42,Citation43 In adults with early inflammatory back pain, 24% and 22% had both lumbar and sacroiliac joint lesions or lumbar spinal lesions only, respectively, which were detectable by whole-body MRI.Citation44 In children, preliminary studies have shown that changes in lumbosacral spine are less frequent and occur later in the disease course than sacroiliitis.Citation45

Treatment of ERA

Treatment regimens for ERA, many of them based on adults with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, include monotherapy or combination therapy with NSAIDs, DMARDs, or biologic agents. NSAID monotherapy may be appropriate for children with low disease activity and without features of poor prognosis (). However, continuation of NSAID monotherapy for longer than 2 months for children with active arthritis is considered inappropriate.Citation46 Many rheumatologists prefer indomethacin for patients with prominent enthesitis, or other agents in the indolacetic acid group such as diclofenac, sulindac, or tolectin. Some of these agents are not Food and Drug Administration approved for children (see for medication specifics and Food and Drug Administration approval). NSAIDs can be safely used for months as long as laboratory studies are done routinely to monitor for hepatic and renal toxicity (CBC, creatinine, liver function tests [LFTs], and urinalysis several weeks after initiation and then every 6–12 months).

Table 2 American College of Rheumatology juvenile idiopathic arthritis treatment guideline features of poor prognosis and disease activity levelsCitation46

Table 3 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for enthesitis-related arthritis treatment

Methotrexate (MTX) is one of the most commonly used DMARDs in JIA. The efficacy and safety of MTX have been established in JIA.Citation47,Citation48 MTX is recommended as initial treatment for children with oligo- and polyarticular disease, depending upon disease activity and features of poor prognosis.Citation46 MTX is a folic acid analog, a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase, and modulates the effect of inflammatory cells and cytokines. The typical dose is 10–15 mg/m2 per week orally or subcutaneously.Citation49,Citation50 At doses greater than 10 mg/m2 per week, the bioavailability and side effect profile of subcutaneous MTX is better than oral.Citation51 MTX typically takes 6–8 weeks before clinical benefit is achieved. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, oral ulcerations, hepatotoxicity, and cytopenias. The recent American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommend checking CBC, LFTs, and creatinine prior to initiation, approximately 1 month after initiation, and then every 3–4 months thereafter if prior results are normal and the dose is stable.Citation46 Although MTX is effective for arthritis, its efficacy for enthesitis, sacroiliitis, and inhibition of structural damage has not been assessed in children with ERA.

Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is another frequently used DMARD in JIA. In one open-label multicenter study, children with HLA-B27-positive oligoarthritis responded well to 1 year of therapy.Citation52 In another 26-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of juvenile SpA, there was no significant difference between SSZ and placebo in active joint count, tender entheses count, pain visual analog scale, or spinal flexion. However, subjects who received SSZ had a significant improvement in the physician and patient assessments of overall improvement.Citation53 SSZ is an analog of 5-aminosalicylic acid linked to sulfapyridine; therefore, it has some inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. Like MTX, SSZ is recommended following a trial of NSAIDs for ERA patients with moderate or high disease activity.Citation46 A typical dose is 30–50 mg/kg per day orally. The dose is titrated over several weeks, and clinical improvement is expected 6–8 weeks after initiation. Side effects include gastrointestinal upset, cytopenias, hepatotoxicity, hypogammaglobulinemia, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. It is recommended to check CBC, LFTs, and creatinine prior to initiation, approximately 1 month after initiation, and then every 3–4 months thereafter if prior results are normal and the dose is stable.

Biologic agents currently approved for the treatment of the nonsystemic forms of JIA are abatacept and the antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents etanercept and adalimumab. Anti-TNF agents have established efficacy in adults for arthritis, enthesitis, and spinal disease. Analyses from an observational pediatric registry demonstrated that anti-TNF agents were effective and safe in patients with ERA who were previously unresponsive to one or more DMARDs.Citation54 However, sustained remission on medication was difficult, and no one achieved remission off medication.Citation54 In another retrospective case series of ten juvenile SpA patients, anti-TNF therapy was effective for both enthesitis and synovitis.Citation55 The typical dose for etanercept is 0.8 mg/kg subcutaneously per week (maximum 50 mg). The typical adalimumab dose is 20 mg or 40 mg subcutaneously every other week for weight less than or greater than 30 kg, respectively. Testing for latent tuberculosis must be performed prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy and yearly thereafter. Side effects of anti-TNFs include risk of infection, cytopenias, hypersensitivity reaction, psoriasis, demyelination, and malignancy.

Anti-TNF agents are effective in adults with early axial inflammation that is detectable by MRI but not by radiographs.Citation56 Once sacroiliitis has developed and damage is detectable on radiographs, DMARDs and anti-TNF agents may help symptomatically, but they do not inhibit progression of axial structural damage.Citation57–Citation60

Prognosis

Observational studies suggest that ongoing disease activity in ERA for more than 5 years predicts disability.Citation61 Tarsitis, HLA-B27 positivity, hip arthritis within the first 6 months, and disease onset after age 8 years are associated with disease progression.Citation32,Citation62 In comparison with other JIA categories, ERA is associated with worse function, quality of life, and pain,Citation63 as well as a smaller likelihood of attaining inactive disease 1 year after treatment initiation.Citation64 Disease remission occurs in less than 20% of children with ERA 5 years after diagnosis.Citation61

As our understanding of the pathophysiology of ERA, enthesitis, and sacroiliitis improves and with the advent of additional biologic therapies, the prognosis of children and adolescents with ERA will likely improve.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr David Sherry for his critical review of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KarvonenMViik-KajanderMMoltchanovaELibmanILaPorteRTuomilehtoJIncidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project GroupDiabetes Care200023101516152611023146

- Solau-GervaisERobinCGambertCPrevalence and distribution of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a region of Western FranceJoint Bone Spine2010771474920034832

- OenKTuckerLHuberAMPredictors of early inactive disease in a juvenile idiopathic arthritis cohort: results of a Canadian multicenter, prospective inception cohort studyArthritis Rheum20096181077108619644903

- YilmazMKendirliSGAltintasDUKarakocGBInalAKilicMJuvenile idiopathic arthritis profile in Turkish childrenPediatr Int200850215415818353049

- SaurenmannRKRoseJBTyrrellPEpidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a multiethnic cohort: ethnicity as a risk factorArthritis Rheum20075661974198417530723

- WeissPFKlinkAJBehrensEMEnthesitis in an inception cohort of enthesitis-related arthritisArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)2011639130721618453

- PettyRESouthwoodTRMannersPInternational League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001J Rheumatol200431239039214760812

- CassidyJTPettyRLaxerRMLindsleyCTextbook of pediatric rheumatology6th edPhiladelphia, PAElvesier2011

- Burgos-VargasRClarkPAxial involvement in the seronegative enthesopathy and arthropathy syndrome and its progression to ankylosing spondylitisJ Rheumatol19891621921972526221

- FlatoBHoffmann-VoldAMReiffAForreOLienGVinjeOLong-term outcome and prognostic factors in enthesitis-related arthritis: a case-control studyArthritis Rheum200654113573358217075863

- WeissPFKlinkAJBehrensEMPrevalence of enthesitis in pediatric patients with Enthesitis-Related ArthritisArthritis Rheum20106210S98S99

- RachlisABabynPLobo-MuellerEWhole body magnetic resonance imaging in juvenile spondyloarthritis: will it provide vital information compared to clinical exam alone?Arthritis Rheum20116310S292

- ResnickDNiwayamaGEntheses and enthesopathy. Anatomical, pathological, and radiological correlationRadiology19831461196849029

- ResnickDFeingoldMLCurdJNiwayamaGGoergenTGCalcaneal abnormalities in articular disorders. Rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and Reiter syndromeRadiology19771252355366910045

- NebenzahlIIRonARostokerNNebenzahl, Ron, and Rostoker replyPhys Rev Lett19896225301210040154

- AnsellBJuvenile spondylitis and related disordersAnkylosing SpondylitisMollJEdinburgh, UKChurchill Livingstone1980

- SherryDDSappLREnthesalgia in childhood: site-specific tenderness in healthy subjects and in patients with seronegative enthesopathic arthropathyJ Rheumatol20033061335134012784411

- ManderMSimpsonJMMcLellanAWalkerDGoodacreJADickWCStudies with an enthesis index as a method of clinical assessment in ankylosing spondylitisAnn Rheum Dis19874631972023107483

- GormanJDSackKEDavisJCJrTreatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alphaN Engl J Med2002346181349135611986408

- MaksymowychWPMallonCMorrowSDevelopment and validation of the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis IndexAnn Rheum Dis200968694895318524792

- Heuft-DorenboschLSpoorenbergAvan TubergenAAssessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitisAnn Rheum Dis200362212713212525381

- GladmanDDInmanRDCookRJInternational spondyloarthritis interobserver reliability exercise – the INSPIRE study: II. Assessment of peripheral joints, enthesitis, and dactylitisJ Rheumatol20073481740174517659754

- BraunJBrandtJListingJTreatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trialLancet200235993131187119311955536

- D’AgostinoMASaid-NahalRHacquard-BouderCBrasseurJLDougadosMBrebanMAssessment of peripheral enthesitis in the spondylarthropathies by ultrasonography combined with power Doppler: a cross-sectional studyArthritis Rheum200348252353312571863

- SprottHJeschonneckMGrohmannGHeinGMicrocirculatory changes over the tender points in fibromyalgia patients after acupuncture therapy (measured with laser-Doppler flowmetry)Wien Klin Wochenschr20001121358058610944816

- D’AgostinoMABrebanMBrasseurJLCanaleMMagaroMUltrasonographic (US) assessment of spondyloarthropathy (SpA) enthesitis, displays vascularization change specific of inflammatory process abstractArthritis Rheum200144Suppl 9S95

- SpadaroAIagnoccoAPerrottaFMModestiMScarnoAValesiniGClinical and ultrasonography assessment of peripheral enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitisRheumatology201150112080208621875877

- Jousse-JoulinSBretonSCangemiCUltrasonography for detecting enthesitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritisArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163684985521312344

- KirisAKayaAOzgocmenSKocakocEAssessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis by power Doppler ultrasonographySkeletal Radiol200635752252816470394

- RudwaleitMvan der HeijdeDLandeweRThe development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selectionAnn Rheum Dis200968677778319297344

- RudwaleitMMetterAListingJSieperJBraunJInflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis: a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteriaArthritis Rheum200654256957816447233

- StollMLBhoreRDempsey-RobertsonMPunaroMSpondyloarthritis in a pediatric population: risk factors for sacroiliitisJ Rheumatol201037112402240820682668

- SpadaroAIagnoccoABaccanoGCeccarelliFSabatiniEValesiniGSonographic-detected joint effusion compared with physical examination in the assessment of sacroiliac joints in spondyloarthritisAnn Rheum Dis200968101559156318957488

- WilliamsonLDockertyJLDalbethNMcNallyEOstlereSWordsworthBPClinical assessment of sacroiliitis and HLA-B27 are poor predictors of sacroiliitis diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging in psoriatic arthritisRheumatology (Oxford)2004431858813130147

- SieperJRudwaleitMBaraliakosXThe Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritisAnn Rheum Dis200968Suppl 2ii14419433414

- TuiteMJSacroiliac joint imagingSemin Musculoskelet Radiol2008121728218382946

- PuhakkaKBJurikAGEgundNImaging of sacroiliitis in early seronegative spondylarthropathy. Assessment of abnormalities by MR in comparison with radiography and CTActa Radiol200344221822912694111

- UnluEPamukONCakirNColor and duplex Doppler sonography to detect sacroiliitis and spinal inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Can this method reveal response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy?J Rheumatol200734111011617216679

- ArslanHSakaryaMEAdakBUnalOSayarliogluMDuplex and color Doppler sonographic findings in active sacroiliitisAJR1999173367768010470902

- KlauserAHalpernEJFrauscherFInflammatory low back pain: high negative predictive value of contrast-enhanced color Doppler ultrasound in the detection of inflamed sacroiliac jointsArthritis Rheum200553344044415934066

- SturrockRDClinical utility of ultrasonography in spondyloarthropathiesCurr Rheumatol Rep200911531732019772825

- WeberUHodlerJJurikAGAssessment of active spinal inflammatory changes in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: validation of whole body MRI against conventional MRIAnn Rheum Dis201069464865319416801

- BennettANMarzo-OrtegaHRehmanAEmeryPMcGonagleDThe evidence for whole-spine MRI in the assessment of axial spondyloarthropathyRheumatology201049342643220064871

- Marzo-OrtegaHMcGonagleDO’ConnorPBaseline and 1-year magnetic resonance imaging of the sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine in very early inflammatory back pain. Relationship between symptoms, HLA-B27 and disease extent and persistenceAnn Rheum Dis200968111721172719019894

- BrophySMackayKAl-SaidiATaylorGCalinAThe natural history of ankylosing spondylitis as defined by radiological progressionJ Rheumatol20022961236124312064842

- BeukelmanTPatkarNMSaagKG2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic featuresArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163446548221452260

- WooPSouthwoodTRPrieurAMRandomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of low-dose oral methotrexate in children with extended oligoarticular or systemic arthritisArthritis Rheum20004381849185710943876

- GianniniEHBrewerEJKuzminaNMethotrexate in resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Results of the USA-USSR double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group and The Cooperative Children’s Study GroupN Engl J Med199232616104310491549149

- WallaceCAGianniniEHSpaldingSJChildhood Arthritis Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA)Trial of early aggressive therapy in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritisArthritis Rheum20111219 [Epub ahead of print]

- TynjalaPVahasaloPTarkiainenMAggressive combination drug therapy in very early polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ACUTE-JIA): a multicentre randomised open-label clinical trialAnn Rheum Dis20117091605161221623000

- TukovaJChladekJNemcovaDChladkovaJDolezalovaPMethotrexate bioavailability after oral and subcutaneous dministration in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritisClin Exp Rheumatol20092761047105320149329

- AnsellBHallMLoftusJA multicenter pilot study of sulphasalazine in juvenile chronic arthritisClin Exp Rheumatol199192011676352

- Burgos-VargasRVazquez-MelladoJPacheco-TenaCHernandez-GardunoAGoycochea-RoblesMVA 26 week randomised, double blind, placebo controlled exploratory study of sulfasalazine in juvenile onset spondyloarthropathiesAnn Rheum Dis2002611094194212228171

- OttenMHPrinceFHTwiltMTumor necrosis factor-blocking agents for children with enthesitis-related arthritis – data from the dutch arthritis and biologicals in children register, 1999–2010J Rheumatol201138102258226321844151

- TseSMBurgos-VargasRLaxerRMAnti-tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade in the treatment of juvenile spondylarthropathyArthritis Rheum20055272103210815986366

- HaibelHRudwaleitMListingJEfficacy of adalimumab in the treatment of axial spondylarthritis without radiographically defined sacroiliitis: results of a twelve-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial followed by an open-label extension up to week fifty-twoArthritis Rheum20085871981199118576337

- HaibelHBrandtHCSongIHNo efficacy of subcutaneous methotrexate in active ankylosing spondylitis: a 16-week open-label trialAnn Rheum Dis200766341942116901959

- van der HeijdeDLandeweRBaraliakosXRadiographic findings following two years of infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitisArthritis Rheum200858103063307018821688

- van der HeijdeDSalonenDWeissmanBNAssessment of radiographic progression in the spines of patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab for up to 2 yearsArthritis Res Ther2009114R12719703304

- van der HeijdeDLandeweREinsteinSRadiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanerceptArthritis Rheum20085851324133118438853

- FlatoBAaslandAVinjeOForreOOutcome and predictive factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile spondyloarthropathyJ Rheumatol19982523663759489836

- FlatoBSmerdelAJohnstonVThe influence of patient characteristics, disease variables, and HLA alleles on the development of radiographically evident sacroiliitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritisArthritis Rheum200246498699411953976

- WeissPFBeukelmanPSchanbergTKimuraLEColbertYInvestigatorsRAEnthesitis is a significant predictor of decreased quality of life, function, and arthritis-specific pain across juvenile arthritis (JIA) categories: preliminary analyses from the CARRAnet RegistryArthritis Rheum20116210S105

- DonnithorneKJCronRQBeukelmanTAttainment of inactive disease status following initiation of TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: enthesitis-related arthritis predicts persistent active diseaseJ Rheumatol201138122675268122089470