Abstract

Increasing numbers of adolescents are being diagnosed with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, the two main subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease. These young people face many short- and long-term challenges; one or more medical therapies may be required indefinitely; their disease may have great impact, in terms of their schooling and social activities. However, the management of adolescents with one of these incurable conditions needs to encompass more than just medical therapies. Growth, pubertal development, schooling, transition, adherence, and psychological well-being are all important aspects. A multidisciplinary team setting, catering to these components of care, is required to ensure optimal outcomes in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease.

Introduction

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) comprise two main subtypes: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).Citation1,Citation2 These incurable conditions lead to chronic inflammatory changes in the gastrointestinal tract that may manifest as pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and impaired linear growth. Although the exact pathogenesis of IBD is not yet elucidated, a number of recent advances have illustrated the importance of genetic elements, the intestinal microflora, and innate responses of the host.Citation2 While both CD and UC may present at any age, the peak age of onset is between 15–35 years of age; consequently, many individuals are diagnosed while adolescents.Citation3

The effects of IBD in adolescence extend far beyond the physical manifestations of the disease. Effective management of IBD in the adolescent demands an holistic model of care, with recognition of the many wider effects on the individual and their family.

Adolescence is a period of major physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. These include the establishment of identity, honing of cognitive abilities and social skills, shaping of belief systems, establishment of independence from parents, and development of adult relationships, including those of a romantic nature.Citation4 Along with these key challenges, adolescents with IBD are also faced with the challenge of navigating the transition from family-centered pediatric care to an adult-oriented model of health care. This review will summarize some key aspects of IBD in adolescents, and present key principles for management of IBD in this age group.

The inflammatory bowel diseases

Although CD and UC share common elements, they also have specific differentiating features. CD encompasses inflammatory changes in any section of the gut, from the mouth to the anus.Citation2 Perioral (eg, lip swelling) and perianal (eg, perianal fistula) manifestations may also occur. Endoscopically and histologically, the typical features of CD are aphthoid ulcers, deeper serpiginous ulceration, transmural inflammation, and patchy changes (skip lesions). The presence of non-caseating granulomata in the lamina propria is characteristic of CD, but these are not universally present. Although most adolescents with CD have purely inflammatory changes at diagnosis, many will subsequently progress to develop structuring or fistulizing disease over time.Citation5

On the other hand, UC is characterized by colonic inflammation, extending proximally from the rectum for a variable distance.Citation2 Endoscopic features include granularity, ulceration, and increased friability. Histologically, the inflammatory changes are superficial and continuous. A small number of individuals diagnosed with IBD, including adolescents, will have endoscopic and histologic findings at the time of diagnosis that do not differentiate between UC and CD: the term IBD-unclassified (IBDU) should be used for this situation.Citation6,Citation7 Generally, with the passage of time and the evolution of the pattern and features of inflammation, IBDU is able to be reclassified as CD or UC.Citation6,Citation7 One report indicated that IBDU is reclassified as UC more commonly.Citation8 Some adolescents may be classified as having indeterminate colitis. This term should be used when the distinction between UC and CD remains unclear, even after colectomy and histopathological examination of the resected colon.Citation6,Citation7

A number of large cohort studies illustrate that children and adolescents with CD and UC have more extensive disease at diagnosis (ie, involve more bowel length) and follow a more severe disease course over time, compared to adult cohorts.Citation9,Citation10 For instance, CD involves the upper gut (proximal to the terminal ileum) in more than 50% of children and adolescents, but is not noted commonly in adults.Citation9,Citation11 Furthermore, CD is more frequently panenteric in pediatric case series (43%) than in adults (3%).Citation9 Overall, more extensive disease is also seen in adolescent UC. Up to three-quarters of children and adolescents with UC have pancolitis, while few have isolated proctitis.Citation9 Furthermore, those who have proctitis or limited left-sided disease at diagnosis often have extension of disease in the subsequent 2 years. These features contrast greatly with the patterns seen in adults who are diagnosed with UC: many have left-sided disease or proctitis; early extension is less commonly seen.Citation9

The pathogenesis of IBD

Although our current understanding of the pathogenesis of CD and UC is incomplete, it is clear that genetics, the gut flora, and host responses are three key elements.Citation2 A large number of susceptibility genes are now recognized; many of these have important roles in elements of host defense, and some have a bias towards earlier onset of disease (including in adolescence).Citation12–Citation14 Although a number of microorganisms have been considered as putative causative agents for IBD, there are not yet data to implicate one individual organism, or group of organisms. Alterations in the diversity of the bacterial elements of the intestinal microbiota have been demonstrated with IBD.Citation15,Citation16

Epidemiology of IBD

Around one-quarter of individuals with IBD are diagnosed in the first 20 years of life.Citation17,Citation18 Of those diagnosed within these 2 decades, most are diagnosed in adolescence, with rates increasing from early in the second decade of life.Citation3 In addition, reports from different countries demonstrate increasing rates of IBD, especially in adolescence.Citation3,Citation19,Citation20 Studies conducted in Australia show that the incidences of both CDCitation21 and UCCitation22 have increased more than ten-fold in pediatric populations during recent decades. The reasons for the observed changes in incidence are unclear, but they may reflect changes in lifestyle, diet, urbanization, or other environmental changes.

Presentation patterns of IBD in adolescents

Although adolescents with IBD may present with a wide range of symptoms, particular features unique to this age group are poor linear growth and delayed pubertal development. The classical presentation of CD in children and adolescence comprises pain, diarrhea, and weight loss, while UC presents most commonly with bloody diarrhea.Citation1,Citation23 Adolescents may also present with a range of atypical symptoms. These may include other gastrointestinal complaints, such as lip swelling and oral ulceration.Citation2,Citation23 Extra-intestinal manifestations (EIM) of IBD can also be present at diagnosis.Citation24,Citation25 EIMs include axial or peripheral arthritis, skin rashes (eg, erythema nodosum), and eye diseases (eg, uveitis). The presence of less classical symptoms may delay recognition and diagnosis, while also increasing morbidity and distress, and compromising growth further.

The psychosocial impact of IBD in adolescents

Numerous factors may impact on the psychological well-being of young people with IBD. These include unpredictable, unpleasant, and embarrassing symptoms; complex, demanding treatment regimens; treatment-related side effects; the ever-looming threat of exacerbations of the disease; and the requirement for “mutilating” surgical procedures.Citation4,Citation26–Citation28 In particular, “ostomy” surgery is associated with issues of body image, feelings of body intrusion, additional challenges in gaining independence, and secrecy issues relating to the stoma.Citation29 Adolescents with IBD frequently describe themes of discomfort and vulnerability, viewing themselves as different, and loss of control over their lives and futures.Citation30

A number of studies have suggested that young people with IBD experience a significantly higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, compared with healthy controls.Citation31–Citation35 Adolescents with IBD demonstrate higher levels of internalizing disorders (anxiety and depression).Citation33–Citation36 The rate of depression may be as high as 25%; it is often under-recognized both by parents and health care professionals. The rate of depression in young people with IBD is at least equal to that seen in adolescents with other chronic diseases, including diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and non-organic abdominal pain.Citation31,Citation37–Citation39 There is also a high prevalence of externalization (behavioral disorders), particularly in adolescent boys with IBD.Citation33,Citation35 These problems are characterized by increased aggression, communication difficulties, and withdrawal behavior.

These psychosocial challenges may have wide-ranging implications for the life of the adolescent with IBD. There is a higher reported rate of school absenteeism, less ability and inclination to socialize with peers, and lower levels of self-confidence in flirtation and establishing romantic relationships.Citation40 Engstrom et alCitation35 reported lower levels of self-esteem in adolescents with IBD, although other studies have failed to demonstrate any difference from healthy controls.Citation32 There is a tendency for young people with IBD to demonstrate higher levels of avoidance behavior.Citation28 The development of peer relationships and autonomy also may be compromised,Citation41 along with greater tendency developed towards seeking emotional support from family members, rather than peers.Citation42 This may lead to delays in emotional maturation and establishment of autonomy from parents and the social circle of the immediate family.

Quality of life in adolescents with IBD

The World Health Organization defines health-related quality of life (QOL) (HRQOL) as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”.Citation43 There are increasing data that indicate the considerable impact of the psychosocial challenges imposed by a diagnosis of IBD on the QOL of young people with IBD.

Adler et alCitation44 reported lower QOL in college students with IBD, and poorer adjustment to college life, compared with healthy peers. Adolescents with IBD appear to have greater impairments of QOL than younger children.Citation45 There are gender differences in reported effects on QOL. Adolescent males are more focused on the effects of IBD on strength, and growth delay, whereas adolescent females appear to be more concerned by the effects on weight, self-image, and relationships.Citation30,Citation41,Citation46 In one study, adolescent males were reported to experience adverse effects on emotional and physical well-being, as well as on family functioning.Citation47 By contrast, adolescent females in this study experienced only negative impact on family functioning.Citation47 The effects on HRQOL in adolescent males may be attributed to greater levels of anxiety and depression. These internalizing symptoms, which may be related to the unpredictable nature of IBD, have been shown to have strong correlation with HRQOL.Citation33 Higher levels of externalizing symptoms are also associated with reduced QOL.Citation48

A number of studies have demonstrated correlation between disease activity and HRQOL;Citation30,Citation41,Citation45,Citation48–Citation51 but, other studies have failed to confirm this relationship.Citation42 It seems likely that any proportion of the variance in HRQOL directly related to disease activity is small.Citation49 By contrast, it is interesting to note that there appears to be a well-described association between functional symptoms and reduced QOL in adults with IBD.Citation52 Coexistent functional symptomatology is well-recognized in patients with IBD. Up to two-thirds of individuals with CD, and one-third of people with UC, experience symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.Citation52 Although there are no studies that directly assess the impacts of such symptoms upon QOL, functional symptoms are associated with higher rates of anxiety in children with IBD.Citation53

Chronic illness demands more sophisticated coping strategies for the adolescent with IBD than the day-to-day challenges of life experienced by their healthy peers. MacPhee et alCitation42 have suggested that young people with IBD often rely on their parents’ abilities to cope. Consequently, there is a negative impact on HRQOL, if the family utilizes ineffective or maladaptive coping mechanisms. Protective factors for QOL have been identified for adolescents with IBD. These include: a greater degree of intimacy, satisfaction with social support networks, and familial positive coping strategies.Citation42 In adolescents, a positive outlook has been shown to be associated with greater QOL.Citation50

An understanding of the risk factors associated with reduced QOL, and the protective factors that ameliorate the effects of disease on HRQOL, may guide health care professionals in addressing these issues. As well as optimal medical management of the disease process, to limit the burden of disease symptomatology, a more holistic approach to care is required.

The literature on adults suggests that direct management of the psychiatric morbidity experienced by individuals with IBD is associated with an increased QOL.Citation52 A pilot, twelve-week study of cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents with IBD led to a reported reduction in depressive symptoms, although direct effects on overall QOL were not measured.Citation54 In addition, a broader approach of therapeutic maneuvers, to support families in developing effective coping mechanisms, may well be beneficial to improve QOL in adolescent patients.

Medical management of IBD in adolescents

In general, the medical management of both CD and UC in adolescence comprises specific drugs to induce remission, followed by other therapies to ensure maintenance of remission. The various therapeutic options need to be considered within the context of the individual patient, their individual disease pattern, disease complications, and the availability of the specific therapy. The potential risks of side effects for any specific therapy need to be balanced with the expected benefits. Candid and open discussions with the adolescent patient and their parents will often be required.

The drug therapies utilized to induce remission in active CD include: corticosteroids (CS), antibiotics, and biological therapies. Corticosteroids have long been considered the principal therapy for active CD, and continue to be widely used in some centers. Although CS may improve symptoms, there is increasing recognition that they lead to relatively low rates of mucosal healing, and have unacceptable side effect profiles, especially for adolescents.Citation5,Citation55 Although budesonide has substantially fewer systemic side effects than oral prednisone, it has also less efficacy, and it appears to have optimal benefits only for terminal ileal CD.Citation55

Metronidazole, separately or in combination with ciprofloxacin, may have roles in the management of mildly active luminal CD, and perianal and perioral diseases.Citation56 These antibiotics may also have roles in the management of disease flares, as alternatives to corticosteroids.Citation57

Biological therapies have clear roles in the induction of remission in severe CD, and in the subsequent maintenance of disease, with ongoing dosing. The efficacy and safety of both infliximabCitation58 and adalimumabCitation59 have been considered in children and adolescents. Although concerns remain about potential side effects, the significant benefits, in terms of achieving remission, high rates of mucosal healing, and enhancing growth need to be considered strongly, in an adolescent with severe disease complicated by growth failure and/or pubertal delay. Although there is developing evidence to support the early introduction of these drugs (the top-down approach),Citation60 this is limited in many areas (such as, New Zealand and Australia) by access requirements.Citation61

After the establishment of remission, the key goal of ongoing management in adolescents with CD is maintenance of remission (preventing relapse). CS and antibiotics do not have roles in the maintenance of remission, and the 5-aminosalicylates (eg, mesalazine) have only a limited role.Citation56 By contrast, immunosuppressive drugs have defined roles in the maintenance of remission of CD in adolescence. Thiopurines (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) are typically used first, with methotrexate tending to be used in settings of thiopurine failure or intolerance.Citation62 Early use of thiopurines in moderate-severe disease is shown to lead to less requirement for CS, more prolonged remission, and better growth.Citation63 However, both thiopurines and methotrexate are associated with various side effects, including bone marrow suppression, hepatotoxicity, and increased sun sensitivity. The thiopurines are also linked with idiopathic pancreatitis, typically leading to vomiting and epigastric pain during the first 7–10 days after initiation. Monitoring of the thiopurine metabolites (6-thioguanine nucleotide and 6-methyl mercaptopurine) can help in optimizing dosing, preventing adverse effects, and indicating poor adherence.Citation64 Biologic drugs, if used successfully to induce remission, can be continued as maintenance therapy in standard regimens.Citation65

Therapies to induce remission in active UC include CS and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) agents. Adolescents with acute severe colitis (ASC) will usually require intravenous CS, with consideration for rescue therapy if there is no response. Medical therapies for failed CS in ASC include cyclosporine or tacrolimus,Citation66 or a biological drug.Citation67,Citation68 Adolescents who fail medical therapy will require colectomy in this instance.

The 5-ASA drugs tend to be the mainstay in maintenance of remission.Citation69 These medications can be delivered orally or rectally (however, this route is often not favored by adolescents). Although numerous studies support the early introduction of thiopurines in moderate-severe CD, there is less data in UC. Recently, a prospective multicenter study evaluated the outcomes of thiopurines in UC in 394 children and adolescents recruited at diagnosis.Citation70 Of this group, 197 patients received thiopurines (half within the first 3 months of diagnosis). Of the 133 patients re-evaluated after 12 months, 65 were in remission, without CS or other therapy.

Methotrexate may have a role when UC is unresponsive to a thiopurine, or when there is intolerance, but this is currently supported only by limited controlled case series data.Citation57,Citation71 Other drugs (such as thalidomide, tacrolimus, or mycophenylate) may play a role in the maintenance of remission, but the data supporting these is less clear.Citation57

A recent report demonstrated the benefits of infliximab in pediatric UC.Citation68 The outcomes of 52 prospectively recruited children and adolescents were followed for a median of 30 months. CS-free remission was seen in 38% of these children at 12 months, with 21% in remission after 24 months. After 2 years of follow-up, 39% of this group had undergone colectomy. An Italian study group has also reviewed their experience with infliximab in children and adolescents with UC.Citation72 These 22 patients had been treated with infliximab using a three-dose induction course and ongoing maintenance dosing (8-weekly). Some of the group had acute severe colitis with no response to CS, while others had a protracted course with/without CS dependency. Overall, twelve of the 22 subjects had full response, with CS-free remission after 12 months, and six others had partial response. Seven subjects required colectomy (only one during the acute period).

In addition to the standard medical therapies, a number of other therapies may be considered by adolescents and their parents. Fish oilsCitation73 and probioticsCitation74 may play adjunctive roles, particularly in UC. Adolescents and/or their parents may consider one or more complementary or alternative medication (CAM) agents. Given that CAM agents are commonly used in adolescent IBD populations,Citation75 practitioners should be aware of this and remember to ask carefully about CAM usage.

Surgical management of IBD in adolescents

A number of adolescents with IBD will require surgical intervention within the first years after diagnosis. The cumulative rate of surgery in one series of 404 children and adolescents with CD was 20% at 3 years, and 34% at 5 years.Citation10 Surgery for CD is not considered curative; surgery is often focused upon managing a disease complication. Specific indications include the management of perianal disease, resection of disease unresponsive to medical therapy, and resection of fibrotic strictures. When luminal disease is unresponsive to medical therapies, surgery that involves a defunctioning procedure (or a limited resection) might permit relief from symptoms and resumption of normal growth patterns. However, the risks and benefits of such an intervention need to be carefully discussed with the adolescent and their family. A period of 1–2 weeks hospital stay for a surgical procedure, and a further period of convalescence at home before returning full time to school, may be a reasonable option in a teenager with very disabling CD preventing school attendance, limiting social interaction and interrupting growth.

In adolescents with UC the indications for colectomy include: ASC unresponsive to medical therapy, severe colitis complicated by toxic megacolon and/or perforation, intractable chronic colitis unresponsive to medical therapies and also following the finding of precancerous changes. Although colectomy in an adolescent with UC will remove the complete focus of disease, there remain concerns about subsequent issues, such as pouchitis, and altered fertility. Newby et alCitation8 reported that 17.6% of 72 children with UC underwent one or more major operations over the period of study, with a mean time of 1.92 years to the first procedure.

Management of nutrition and nutritional therapy in adolescents with IBD

Almost all adolescents with CD, and many with UC, have concerns about poor weight gain, impaired linear growth, or delayed puberty, at diagnosis or subsequently.Citation2,Citation76,Citation77 Poor weight gain typically results from reduced oral intake, due to anorexia, early satiety, nausea, or pain. Impaired linear growth reflects nutritional impairment. The systemic circulation of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6, in particular, modulates the activity of key mediators of growth, especially insulin-like growth factor 1, thereby affecting growth hormone activity, while also altering growth plate responses.Citation78

In addition, active IBD can adversely affect pubertal development in adolescents, especially in males with CD.Citation76 Failure to adequately control active disease during these crucial years may lead to significant consequences upon pubertal growth, leading ultimately to reduced final height acquisition.Citation79,Citation80

Consequently, assessment of growth and pubertal status at diagnosis of IBD in an adolescent, along with ongoing close monitoring of growth parameters throughout adolescence, is an essential aspect of monitoring. Nutritional interventions are often required in adolescents, especially those with CD. These include supplementary enteral nutrition, to enhance caloric intake and maintain remission, and exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN), to induce or reinduce remission in active CD.Citation81 EEN comprises the provision of a complete liquid diet, along with exclusion of standard dietary components. It should be considered the preferred and optimal therapy to induce remission in adolescent CD, due to its combination of high efficacy and low adverse effect profile.Citation82,Citation83 EEN protocols and utility have been considered in recent reviews of this therapy in pediatric and adolescent CD.Citation82,Citation83

Typically, EEN is delivered over a period of up to 8 weeks, with regular support, including dietetic and medical review during this time, to ensure that the adolescent is responding adequately, as well as coping psychologically with the absence of solid food in the diet.Citation84 Socially, the absence of food can be stigmatizing during this period, and support from health professionals during this period is vital. Key medical assessments include review of adherence, tolerance of the formula, weight, symptoms, and inflammatory markers. At completion of the period of EEN, normal diet is slowly reintroduced over 7–10 days, with one meal introduced every 3–4 days, along with concurrent reductions in volume of formula.Citation83

EEN is able to induce remission in 80%–85% of children and adolescents with active CD, in most published data, but does not have a role in UC. One meta-analysis of pediatric studies suggested that EEN was equivalent to CS in induction of remission.Citation85 By contrast, a Cochrane review has concluded that CS is superior to EEN. However, this included mainly studies of adult subjects, treated with EEN.Citation86 The outcomes and consequences appear to be different in adult patients with CD than in children and adolescents, with the majority of patients in pediatric studies being in the adolescent age group. The reasons for the differences between responses in adolescents and adults are unclear, but may include disease duration, adherence to therapy, and comorbidities.

In addition to inducing remission, EEN is one of the few current medical therapies recognized to promote high rates of mucosal healing. Borelli and colleaguesCitation87 reported that 74% of a group of 19 children who were managed with EEN had mucosal healing afterwards. This contrasts with the rate of 33% in a comparison group treated with CS to induce remission. An earlier, Italian study demonstrated mucosal improvements in 70% of a group treated with EEN, and 40% of subjects treated with corticosteroids.Citation88

EEN has been shown to yield prompt and significant improvements in nutrition, which include early changes in levels of insulin-like growth factor 1, along with improvements in growth parameters.Citation76,Citation83 EEN also improves bone nutrition, with rapid improvements in markers of bone turnover consequent to EEN therapy.Citation89 In addition to the short-term benefits of EEN, the initial use of EEN has a number of advantages that persist long beyond the initial period of EEN itself.Citation88,Citation90,Citation91 These include more sustained remission and better growth, compared with those treated initially with CS.

There are not yet clear ways to guide the individualization of the length of EEN for each patient. Establishing the rate at which specific inflammatory markers improve may be a potential mechanism to guide the length of therapy. Gerasimidis and colleaguesCitation92 demonstrated that a reduction of calprotectin of >18%, after 30 days of EEN, predicted a clinical response within 8 weeks of therapy. Focused evaluations of EEN, over different time periods, are clearly required. These should be linked with studies that consider how best to evaluate responses to EEN, to be able to predict those who will require a longer duration, as against those who will have a clear induction of remission in a shorter time period.

Adherence to therapy in adolescents with IBD

Successful management of IBD is almost universally dependent on the use of long-term maintenance therapies. Similar to other pediatric chronic diseases, nonadherence rates vary between 38%–66% in children and adolescents with IBD.Citation27,Citation64,Citation93–Citation95 Furthermore, a number of studies document that adherence rates are lowest in adolescents.Citation96–Citation99

The reasons for poor adherence to medication are multiple. IBD is often diagnosed in adolescence, which is a time characterized by a greater desire for autonomy.Citation100 This may lead to delegation to the young person of responsibility for medication adherence, rather than direct supervision by a parent.Citation93 Barriers to adherence for the young person may include remembering to take their medication, and the need to set aside time to take medication. Both children and their parents cite lack of time as the most common barrier to adherence.Citation101

A further challenge to adherence relates to the lack of immediate benefit to be derived from taking medication. It is recognized, in other conditions, that medication adherence rates are lower when diseases are in remission.Citation102,Citation103 Although adolescence is a developmental stage, which is characterized by a transition from short-term thinking to long-term thinking, the timing of this is variable; adolescents’ motivations for action often relate to short-term consequences, rather than long-term health benefits. It may be difficult for the young person to perceive the benefits of taking the medication, especially as long-term adherence is required to maintain remission, even when the young person feels entirely well. Furthermore, exacerbations of disease may occur, even in the context of excellent adherence.Citation101 This may reinforce a sense of uncertainty, or even of futility, surrounding the value of adherence to treatment. Limited knowledge of the disease may mean also that young people may fail to recognize the consequences of nonadherence.

Adolescence is characterized also by a desire to “fit in”, and to be viewed not as different from peers.Citation100 The socially-embarrassing nature of the disease, and the need to take regular medication, may automatically identify a young person with IBD as different, which may contribute to poor adherence. Furthermore, side effects of medication may provide significant barriers to adherence.Citation101,Citation104 These include visible effects, such as steroid-related effects on appearance (with associated impact on body image and self-esteem), as well as fears related to other side effects of treatment.

IBD treatment often involves complex drug therapies, involving multiple medications and frequent dosing. An early study of medication adherence in adults demonstrated that a greater number of medications and greater frequency of dosing were associated with reduced adherence.Citation105 However, other studies have failed to confirm this finding, with some studies suggesting that a greater number of daily doses was associated with improved adherence.Citation106–Citation109 In a recent study of adherence in adolescents with IBD, patients identified increased complexity of medication regimen as a barrier to adherence.Citation101 Specifically, adolescents on monotherapy reported significantly fewer barriers to adherence than those on multiple medications.

Various risk factors for nonadherence in the adolescent population have been described. Family dysfunction, including poor family structure, cohesion, and child discipline has been associated with poor adherence in several studies.Citation93,Citation95 Lower income and minority status have been linked to poorer adherence in some, but not all studies.Citation95 It has been suggested also that poor coping strategies may be related to reduced adherence, though there are limited data to support this theory.Citation95 Finally, psychological stressors, including depression and low self-esteem, are associated with poor adherence in adolescents with various chronic health conditions.Citation95,Citation110,Citation111

Although adherence to medical therapy is crucial to optimizing outcomes, assessment of nonadherence is extremely challenging. Clinician estimates of adherence are notoriously inaccurate.Citation112,Citation113 Self reports and parental reports tend to overestimate adherence.Citation95 Medication measurement techniques, such as assessment of repeat prescriptions or counting pills, do not provide any guarantee that the medication has actually been taken. Even more objective measurements, such as drug levels, may be limited by variable pharmacokinetics, lack of correlation between levels and clinical efficacy, and the problem that, for many medicines, these levels are a reflection only of recent consumption, rather than long-term adherence.Citation4,Citation103

Strategies that improve adherence should lead to better disease control and reduction in disease-related complications. The optimal nature of such strategies remains unclear, but is likely to be multifaceted. This may involve rationalization of treatment regimens; adoption of strategies to organize medication (eg, pill boxes, utilization of electronic reminders, supplies of medication at home and school, etc), patient education, encouraging appropriate and effective development of autonomy, and measures to address psychological and social risk factors for poor adherence.

Monitoring progress in adolescents with IBD

Although clinical assessment (symptom review) remains important in adolescents with IBD, consideration of biochemical monitoring, growth review, and assessment of mucosal healing are also important components. Regular review of symptoms (both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal) and growth measurement are critical. Regular review of adherence is also important.

Regular estimation of inflammatory markers, full blood count, and liver chemistry (every 3 months, in any adolescent on an immunosuppressive drug) along with annual monitoring of absorptive markers (eg, vitamins D and B12, folate, iron) is appropriate. Annual bone age estimation (x-ray of left wrist), from diagnosis and annually through adolescence, is helpful in delineating growth and skeletal development in CD ().Citation114

Table 1 Annual monitoring tests in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease

As noted earlier, achieving mucosal healing is increasingly important, given the impact that it has on the subsequent course of disease.Citation115 A dilemma remains as to the best way to assess mucosal healing. The use of noninvasive markers, such as calprotectin, is advancing.Citation116,Citation117 However, the optimal level to aim for, and the frequency of appropriate measurement, remain unclear. The precise role for fecal calprotectin and/or other noninvasive markers will hopefully become more clear in the coming years.

In addition to the above assessments, an adolescent-focused history is also important; it provides an understanding of the impact of the underlying disease upon the psychological state of the adolescent. This can be facilitated by the use of the HEADSS assessment, which involves asking about key aspects of an adolescent’s life, covering areas such as home, education, activities, employment, drugs, suicidality, sex, and safety.Citation118,Citation119

Transition of adolescents with IBD to adult services

Over the past decade, there has been increasing recognition of the importance of effectively supporting the adolescent with chronic disease in making a transition from care within a pediatric setting, to the adult clinic. There is a danger that these adolescents may not have their needs fully met, either in the family-centered, developmentally-focused pediatric setting (which does not acknowledge their growing independence), or in the adult medical clinic (which acknowledges patient autonomy, reproduction, and employment issues, but may not recognize growth, development, and family issues).Citation120 There is an imperative for clinicians who care for adolescents to understand and address their developmental, psychological, and educational needs, rather than solely their medical care.

The potential adverse effects of poorly managed transition are well documented in many patient groups, including effects on health (for example, worsening glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus,Citation121–Citation124 graft failure in transplant recipients),Citation125,Citation126 and health service use (increased loss to follow-up, with poorer health outcomes in some cases, for survivors of childhood cancerCitation127 and cardiac surgery).Citation128 Literature that directly addresses the adverse health effects of poorly managed transition in IBD is relatively scarce. However, a recent study by Bollegala et alCitation129 identified a significant reduction in outpatient clinic visit frequency, and an increase in documented nonadherence, after transfer to adult care.

Furthermore, the phenotype of childhood-onset IBD is of more severe disease, with a greater potential for complications.Citation9,Citation10 A case control study of 100 adolescents with IBD, compared against adults with disease of equal duration, demonstrated a higher rate of hospital admission, higher immunosuppressant use, and a greater requirement for biological therapy in the adolescent group.Citation130 Therefore, the potential for poorer outcomes and worsening quality of life is huge, if transition to adult care is poorly managed. However, within the IBD community, the importance of effective transition has yet to be universally recognized, and comprehensive transition services for young people with IBD are still uncommon.

Multiple guidelines have been proposed by national medical societies that provide consensus guidance on transitioning adolescents with chronic illness, or IBD, specifically.Citation131–Citation135 However, a single optimal model of transitional care has not been described, and no single model of care will fit all cases, for individual adolescents, clinicians, and institutions. Any transition program must recognize the medical, psychological, social, and educational needs of young people as they move from a child-centered to an adult-oriented health care system. A survey of adult gastroenterologists in the USA reported 73% competence in managing medical aspects of adolescent care, but only 46% competence with developmental and mental health issues.Citation136 Although the perfect “one size fits all” transition program does not exist, minimal requirements for a transition program can be identified.Citation137

Some of the key requirements for transition programs include having a transition policy, active involvement of both adolescent and adult personnel, structured pathways through the transition process (but with flexibility to suit individual needs), addressing knowledge needs of the young adults, and broad, multidisciplinary inputs, whilst also addressing disease-specific care, and generic health education and skills training for young people. It is also important that transition programs address the needs of the parents and families in the move from pediatric to adult care. Although the ultimate aim of transition is to empower the adolescent to gain autonomy and responsibility for their care, this is likely to be a gradual process. It is important to acknowledge the role that parents have played and may continue to play in care.

Several newly-developed tools may prove useful in guiding adolescents through a transition pathway. For example, the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Knowledge Inventory Device (IBD-KID) has been developed and validated as a tool to assess disease-specific knowledge in the adolescent age group.Citation138 The outcomes of this assessment can then be used to focus additional educational activities. This device has been included in the authors’ transition program, but is yet to be formally assessed in this role. Zijlstra et alCitation139 have recently developed the IBD-yourself questionnaire, which was designed to assess self-efficacy in adolescents, as a component of readiness for transition. In addition, a Canadian study developed a tool to highlight knowledge gaps in adolescents proceeding through a transition program.Citation140

Overall, it is important that young people are involved in the development of transition programs, and in the individualization of their own transition to adult care. This will enhance their sense of control and autonomy. Transition is a major life event for young people with chronic illness.Citation120 Although there are limited data to demonstrate improved outcomes related to effective transition in IBD, there is evidence that effective transition may be related to improved health outcomes and service utilization in other chronic conditions.Citation141 Furthermore, there is good evidence of adverse effects related to poorly managed transition to adult care.Citation129 Therefore, the provision of transition services for adolescents with IBD is essential for all centers involved in managing pediatric IBD. However, further research is required to evaluate optimal design, health-related outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of these programs of care.

Summary of overall principles of management of IBD in adolescents

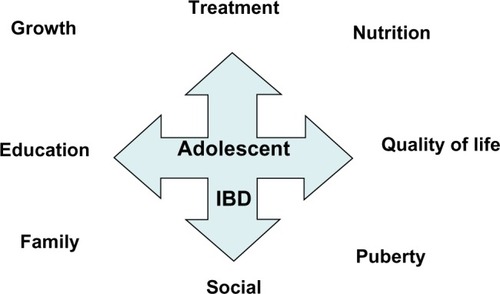

Given the various adverse impacts of this chronic disease, management of IBD in adolescents needs to have a broad perspective, with consideration of more than just medical therapies or surgical interventions. Additional, important key components of the management of IBD in adolescents include growth and nutrition, psychological effects, schooling/education, sports and social aspects, and the impact upon the wider family ().

Figure 1 Multiple aspects of management of IBD in adolescents.

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Consequent to these many and varied impacts, adolescents with IBD should be managed within a multidisciplinary team, with individual practitioners able to provide expertise and experience across these spheres. Furthermore, these various components all need to be delivered within a framework that is adolescent-friendly, holistic, and supportive, yet fostering independence and developing maturity.

General aspects of management for adolescents include having a good, well-balanced diet, encouraging regular exercise, good sleep, and managing stress. Lifestyle choices also need to be discussed with an adolescent; smoking should be avoided, while adolescents should be advised to be careful with alcohol exposure (especially with specific medications or with liver disease). Generally, one should encourage the concept of “looking after your whole body, so it can look after your gut better”.

Conclusion

The period of adolescence poses many challenges, especially for those young people diagnosed with IBD. Both CD and UC can have many and varied adverse impacts upon adolescents, especially with regard to nutrition, growth, and pubertal development. The management of IBD in this age group must take these important factors into account, with care being holistic and multidisciplinary.

Disclosure

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

References

- RuemmeleFMPediatric inflammatory bowel disease: coming of ageCurr Opin Gastroenterol201026433233620571385

- GriffithsAMHugotJPChapter 41, Crohn diseaseWalkerAGouletOKleinmanREPediatric Gastrointestinal Disease4th edHamilton, ON, CanadaBC Decker2004

- BenchimolEIFortinskyKJGozdyraPEpidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of international trendsInflamm Bowel Dis201117142343920564651

- MamulaPMarkowitzJEBaldassanoRNInflammatory bowel disease in early childhood and adolescence: special considerationsGastroenterol Clin North Am2003323967995viii14562584

- CosnesJGower-RousseauCSeksikPCortotAEpidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseasesGastroenterology201114061785179421530745

- GeboesKColombelJFGreensteinAIndeterminate colitis: a review of a concept – what’s in a name?Inflamm Bowel Dis200814685085718213696

- FeakinsRMInflammatory bowel disease biopsies: British Society of Gastroenterology reporting guidelinesJ Clin Pathol925201310.1136/jclinpath-2013-201885 [Epub ahead of print.]

- NewbyEACroftNMGreenMNatural history of paediatric inflammatory bowel diseases over a 5-year follow-up: a retrospective review of data from the register of paediatric inflammatory bowel diseasesJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2008465539534518493209

- Van LimbergenJRussellRKDrummondHEDefinition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood onset inflammatory bowel diseaseGastroenterology2008135411441122

- Vernier-MassouilleGBaldeMSalleronJNatural history of pediatric Crohn’s disease: a population-based cohort studyGastroenterology200813541106111318692056

- LembergDAClarksonCBohaneTDayASThe role of esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy in the initial assessment of children with IBDJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200520111696170016246188

- ImielinskiMBaldassanoRNGriffithsACommon variants at five new loci associated with early onset inflammatory bowel diseaseNat Genet20094121335134019915574

- FrankeAMcGovernDPBarrettJCGenome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility lociNat Genet201042121118112521102463

- GlockerEOKotlarzDBoztugKInflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptorN Engl J Med2009361212033204519890111

- ManSMKaakoushNOMitchellHMThe role of bacteria and pattern-recognition receptors in Crohn’s diseaseNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol20118515216821304476

- KaakoushNODayASHuinaoKDMicrobial dysbiosis in pediatric patients with Crohn’s diseaseJ Clin Microbiol201250103258326622837318

- RogersBHClarkLMKirsnerJBThe epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease: an analysis of a computerized file of 1400 patientsJ Chronic Dis197124127437735146188

- Mir-MadjlessiSHMichenerWMFarmerRGCourse and prognosis of idiopathic ulcerative proctosigmoiditis in young patientsJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr198654570575

- MolodeckyNASoonISRabiDMIncreasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic reviewGastroenterology20121421465422001864

- BenchimolEIGuttmannAGriffithsAMIncreasing incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative dataGut200958111490149719651626

- PhavichitrNCameronDJCatto-SmithAGIncreasing incidence of Crohn’s disease in Victorian childrenJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200318332933212603535

- SchildkrautVAlexGCameronDJSixty-year study of incidence of childhood ulcerative colitis finds eleven-fold increase beginning in 1990sInflamm Bowel Dis20131911622532319

- GriffithsAMSpecificities of inflammatory bowel disease in childhoodBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200418350952315157824

- GreensteinAJJanowitzHDSacherDBThe extra-intestinal complications of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patientsMedicine1976555401412957999

- HyamsJSExtraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in childrenJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr19941917217965480

- DubinskyMSpecial issues in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseWorld J Gastroenterol200814341342018200664

- HommelKADavisCMBaldassanoRNMedication adherence and quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr Psychol2008338864874

- LoonenHJDerkxBHGriffithsAMPediatricians overestimate importance of physical symptoms upon children’s health concernsMed Care20024010996100112395031

- NicholasDBSwanSRGerstleTJStruggles, strengths, and strategies: an ethnographic study exploring the experiences of adolescents living with an ostomyHealth Qual Life Outcomes2008611419091104

- NicholasDBOtleyASmithCChallenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative examinationHealth Qual Life Outcomes200752817531097

- EngstromIInflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: Mental health and family functioningJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr1999284S28S3310204521

- VaistoTAronenETSimolaPPsychosocial symptoms and competence among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and their peersInflamm Bowel Dis2010161273519575356

- De BoerMGrootenhuisMDerkxBHealth-related quality of life and psychosocial functioning of adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200511440040615803032

- MacknerLMCrandallWVSzigethyEMPsychosocial functioning in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200612323924416534426

- EngstromIMental health and psychological functioning in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison with children having other chronic illnesses and with healthy childrenJ Child Psychol Psychiatry19923335635821577899

- EngstromILindquistBLInflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: a somatic and psychiatric investigationActa Paediatr Scand1991806–76406471867081

- BurkePMeyerVKocoshisSDepression and anxiety in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and cystic fibrosisJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19892869489512808268

- BurkePKocoshisSAChandraRDeterminants of depression in recent onset pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19902946086102387796

- RaymerDWeiningerOHamiltonJRPsychological problems in children with abdominal painLancet1984183744394406142160

- CalsbeekHRijkenMBekkersMJSocial position of adolescents with chronic digestive disordersEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200214554354911984153

- van der Zaag-LoonenHJGrootenhuisMALastBFDerkxHHCoping strategies and quality of life of adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseQual Life Res20041351011101915233514

- MacPheeMHoffenbergEJFeranchukAQuality-of-life factors in adolescent inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis1998416119552222

- Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL)Qual Life Res1993221531598518769

- AdlerJRajuSBeveridgeASCollege adjustment in University of Michigan students with Crohn’s and colitisInflamm Bowel Dis20081491281128618512247

- OtleyARGriffithsAMHaleSHealth-related quality of life in the first year after diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200612868469116917222

- MussellMBockerUNagelNPredictors of disease-related concerns and other aspects of health-related quality of life in outpatients with inflammatory bowel diseaseEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200416121273128015618832

- KarwowskiCAKeljoDSzigethyEStrategies to improve quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915111755176419472359

- GrayWNDensonLABaldassanoRNHommellKADisease activity, behavioral dysfunction, and health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20111771581158621674715

- OtleyASmithCNicholasDThe IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200235455756312394384

- DrossmanDAPatrickDLMitchellCMZagamiEAAppelbaumMIHealth-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Functional status and patient worries and concernsDig Dis Sci1989349137913862766905

- PerrinJMKuhlthauKChughtaiAMeasuring quality of life in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: psychometric and clinical characteristicsJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200846216417118223375

- SimrenMAxelssonJGillbergRQuality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated factorsAm J Gastroenterol200297238939611866278

- FaureCGiguereLFunctional gastrointestinal disorders and visceral hypersensitivity in children and adolescents suffering from Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200814111569157418521915

- SzigethyEWhittonSWLevy-WarrenACognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443121469147715564816

- SidoroffMKolhoK-LGlucocorticoids in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseScand J Gastroenterol201247774575022507033

- Kale-PradhanPBZhaoJJPalmerJRWilhelmSMThe role of antimicrobials in Crohn’s diseaseExp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol201373281288

- DayASLedderOLeachSTLembergDACrohns and colitis in children and adolescentsWorld J Gastroenterol201218415862586923139601

- HyamsJCrandallWKugathasanSInduction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in childrenGastroenterology2007132386387317324398

- RussellRKWilsonMLLoganathanSA British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition survey of the effectiveness and safety of adalimumab in children with inflammatory bowel diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther201133894695321342211

- WaltersTDKimMDensonLAComparative effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology201310.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.027 [Epub ahead of print.]

- SchultzMGearryRWalmsleyRNew Zealand Society of Gastroenterology statement on the use of biological therapy in IBDNZ Med J201012313141314

- BoyleBMacknerLRossCA single-center experience with methotrexate after thiopurine therapy in pediatric Crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201051671471720706154

- PunatiJMarkowitzJLererTEffect of early immunomodulator use in moderate to severe pediatric Crohn diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200814794995418306311

- OoiCYBohaneTDLeeDNaidooDDayASThiopurine metabolite levels in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200725894194717402998

- HyamsJWaltersTDCrandallWSafety and efficacy of maintenance infliximab therapy for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease in children: REACH open-label extensionCurr Med Res Opin2011273651662

- BousvarosAKirschnerBSWerlinSLOral tacrolimus treatment of severe colitis in childrenJ Pediatr2000137679479911113835

- YangLSAlexGCatto-SmithAGThe use of biologic agents in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseCurr Opin Pediatr2012245699714

- HyamsJSLererTGriffithsAOutcome following infliximab therapy in ulcerative colitisAm J Gastroenterol201010561430143620104217

- ZeislerBLererTMarkowitzJOutcome following aminosalicylate therapy in children newly diagnosed as having ulcerative colitisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2013561121822847466

- HyamsJSLererTMackDOutcome following thiopurine use in children with ulcerative colitis: a prospective multicenter registry studyAm J Gastroenterol2011106598198721224840

- WillotSNobleADeslandresCMethotrexate in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: An 8-year retrospective study in a Canadian pediatric IBD centerInflamm Bowel Dis201117122521252621337668

- CucchiaraSRomeoEViolaFInfliximab for pediatric ulcerative colitis: a retrospective Italian multicenter studyDig Liver Dis200840Suppl 2S260S26418598998

- TurnerDZlotkinSHShahPSGriffithsAMOmega 3 fatty acids (fish oil) for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20091CD00632019160277

- PhamMLembergDADayASProbiotics: sorting the evidence from the mythsMed J Australia2008188530430818312197

- DayASA review of the use of complementary and alternative medicines by children with inflammatory bowel diseaseFront Pediatr20131924400255

- MoeeniVDayASImpact of inflammatory bowel disease upon growth in children and adolescentsISRN Pediatr2011201136571222389775

- ThomasAGTaylorFMillerVDietary intake and nutritional treatment in childhood Crohn’s diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr199317175818350215

- WaltersTDGriffithsAMMechanisms of growth impairment in pediatric Crohn’s diseaseNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol20096951352319713986

- FergusonASedgwickDMJuvenile onset inflammatory bowel disease: height and body mass index in adult lifeBMJ19943086939125912638205017

- BallingerABSavageMOSandersonIRDelayed puberty associated with inflammatory bowelPediatr Res200353220521012538776

- DayASWhittenKESidlerMLembergDASystematic review: nutritional therapy in paediatric Crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200827429330718045244

- CritchJDayASOtleyARKing-MooreCTeitelbaumJEShashidarHClinical report: the utilization of enteral nutrition for the control of intestinal inflammation in pediatric Crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201254429830522002478

- DayASBurgessLExclusive enteral nutrition and induction of remission of active Crohn disease in childrenExp Rev Clin Immunol201394375384

- DayASWhittenKELembergDAExclusive enteral feeding as primary therapy for Crohn’s disease in Australian children and adolescents: a feasible and effective approachJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200621101609161416928225

- HeuschkelRBMenacheCCMegerianJTBairdAEEnteral nutrition and corticosteroids in the treatment of acute Crohn’s disease in childrenJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200031181510896064

- ZachosMTondeurMGriffithsAMEnteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn’s diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev2007CD00054217253452

- BorrelliOCordischiLCirulliMPolymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled open-label trialClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20064674475316682258

- Berni CananiRTerrinGBorrelliOShort- and long-term therapeutic efficacy of nutritional therapy and corticosteroids in paediatric Crohn’s diseaseDig Liver Dis200638638138716301010

- WhittenKELeachSTBohaneTDWoodheadHJDayASEffect of exclusive enteral nutrition on bone turnover in children with Crohn’s diseaseJ Gastroenterol201045439940519957194

- LambertBLembergDALeachSTDayASLong term outcomes of nutritional management of Crohn’s disease in childrenDig Dis Sci20125782171217722661250

- KnightCEl-MataryWSprayCSandhuBKLong-term outcome of nutritional therapy in paediatric Crohn’s diseaseClin Nutr200524577577915904998

- GerasimidisKNikolaouCKEdwardsCAMcGroganPSerial fecal calprotectin changes in children with Crohn’s disease on treatment with exclusive enteral nutrition: associations with disease activity, treatment response, and prediction of a clinical relapseJ Clin Gastroenterol2011453234234920871409

- HommelKADavisCMBaldassanoRNObjective versus subjective assessment of oral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915458959318985746

- MacknerLMCrandallWVOral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200511111006101216239847

- Oliva-HemkerMMAbadomVCuffariCThompsonRENonadherence with thiopurine immunomodulator and mesalamine medications in children with Crohn diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200744218018417255828

- RapoffMAAdherence to Pediatric Medical RegimensNew YorkKluwer Academic1999

- GavinLAWamboldtMZSorokinNTreatment alliance and its association with family functioning, adherence, and medical outcome in adolescents with severe, chronic asthmaJ Pediatr Psychol199924435536510431501

- McQuaidELKopelSJKleinRBFritzGKMedication adherence in pediatric asthma: reasoning, responsibility, and behaviorJ Pediatr Psychol200328532333312808009

- ThiruchelvemDCharachASchacharRJModerators and mediators of long-term adherence to stimulant treatment in children with ADHDJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140892292711501692

- HolmbeckGNGreenleyRNFranksEBDevelopmental issues and considerations in research and practiceKazdinAEWeiszJPEvidence-Based Psychotherapy for Children and AdolescentsNew YorkGuilford Press20032141

- GreenleyRNStephensMDoughtyARaboinTKugathasanSBarriers to adherence among adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis2009161364119434722

- LoganDZelikovskyNLabayLSpergelJThe Illness Management Survey: identifying adolescents’ perceptions of barriers to adherenceJ Pediatr Psychol200328638339212904450

- MatsuiDMChildren’s adherence to medication treatmentDrotarDPromoting Adherence to Medical Treatment in Chronic Childhood IllnessMahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum Assoc2000135152

- LaGrecaAMBearmanKJAdherence to pediatric treatment regimensRobertsMCHandbook of Pediatric Psychology3rd edNew YorkGuilford Press2003119140

- GreenbergRNOverview of patient compliance with medication dosing: a literature reviewClin Ther1984655925996383611

- ShalanskySJLevyAREffect of number of medications on cardiovascular therapy adherenceAnn Pharmacother200236101532153912243601

- BillupsSJMaloneDCCarterBLThe relationship between drug therapy noncompliance and patient characteristics, health-related quality of life, and health care costsPharmacotherapy200020894194910939555

- MonaneMBohnRLGurwitzJHNoncompliance with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderlyArch Intern Med199415444334378117176

- SharknessCMSnowDAThe patient’s view of hypertension and complianceAm J Prev Med1992831411461632999

- KennardBDStewartSMOlveraRNonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcomeJ Clin Psychol Med Settings20041113139

- KovacsMGoldstonDObroskyDSPrevalence and predictors of pervasive noncompliance with medical treatment among youths with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1992316111211191429414

- CharneyEBynumREldredgeDHow well do patients take oral penicillin? A collaborative study in private practicePediatrics19674021881955006583

- FinneyJWHookRJFrimanPCThe overestimation of adherence to pediatric medical regimensChild Health Care199322429730410130540

- GuptaNLustigRHKohnMAVittinghoffEDetermination of bone age in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease should become part of routine careInflamm Bowel Dis2013191616522552908

- FroslieKJahnsenJMoumBMucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohortGastroenterology2007133241242217681162

- JuddTADayASLembergDATurnerDLeachSTAn update of faecal markers of inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201126101493149921777275

- SidlerMALeachSTDayASFecal S100A12 and fecal calprotectin as noninvasive markers for inflammatory bowel disease in childrenInflamm Bowel Dis200814335936618050298

- GoldenringJRosenDGetting into adolescent headsContemp Pediatr198857590

- GoldenringJRosenDGetting into adolescent heads: an essential updateContemp Pediatr20042164

- VinerRTransition from paediatric to adult care. Bridging the gaps or passing the buck?Arch Dis Child199981327127510451404

- EllemannKNoertved SoerensenJPedersenLEdsbergBAndersenOOEpidemiology and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in a community populationDiabetes Care1984765285326439530

- SnorgaardOEskildsenPVadstrupSNerupJDiabetic ketoacidosis in Denmark: epidemiology, incidence rates, precipitating factors and mortality ratesJ Intern Med198922642232282509623

- ThompsonCCummingsFChalmersJAbnormal insulin treatment behaviour: a major cause of ketoacidosis in the young adultDiabet Med19951254294327648807

- PoundNSturrockNJeffcoateWAge-related changes in glycated haemoglobin in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusDiabet Med19961365105138799652

- KeithDSCantarovichMParaskevasSRecipient age and risk of chronic allograft nephropathy in primary deceased donor kidney transplantTranspl Int20061964965616827682

- WatsonARNon-compliance and transfer from pediatric to adult transplant unitPediatr Nephrol200014646947210872185

- OeffingerKCMertensACHudsonMMHealth care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor StudyAnn Fam Med200421617015053285

- YeungEKayJRooseveltGEBrandonMYetmanATLapse of care as a predictor for morbidity in adults with congenital heart diseaseInt J Cardiol20081251626517442438

- BollegalaNBrillHMarshallJKResource utilization during pediatric to adult transfer of care in IBDJ Crohns Colitis201372e55e6022677118

- GoodhandJDawsonRHefferonMInflammatory bowel disease in young people: the case for transitional clinicsInflamm Bowel Dis201016694795219834978

- BlumRWGarellDHodgmanCHTransition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent MedicineJ Adolesc Health19931475705768312295

- A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needsPediatrics20021106 Pt 21304130612456949

- Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needsPaediatr Child Health200712978579319030468

- BaldassanoRFerryGGriffithsATransition of the patient with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and NutritionJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200234324524811964946

- LeungYHeymanMBMahadevanUTransitioning the adolescent inflammatory bowel disease patient: guidelines for the adult and pediatric gastroenterologistInflamm Bowel Dis201117102169217321910179

- HaitEJBarendseRMArnoldJHTransition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologistsJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2009481616519172125

- Royal College of Physicians of EdinburghThink Transition: Developing the Essential Link Between Paediatric and Adult CareDalkeith, UKARC Scotland2008

- HaalandDDayASOtleyADevelopment and validation of a pediatric IBD knowledge inventory device – the IBD-KIDJ Pediatr Gastronterol Nutr10162013 [Epub ahead of print.]

- ZijlstraMDe BieCBreijLSelf-efficacy in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A pilot study of the “IBD-yourself ”, a disease-specific questionnaireJ Crohns Colitis201379e375e38523537816

- BenchimolEIWaltersTDKaufmanMAssessment of knowledge in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease using a novel transition toolInflamm Bowel Dis20111751131113721484961

- CrowleyRWolfeILockKImproving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic reviewArch Dis Child201196654855321388969