Abstract

Introduction

The years spent in acquiring medical education is considered a stressful period in the life of many students. Students whose mental health deteriorates during this long period of study are less likely to become empathic and productive physicians. In addition to other specific stressors, academic examinations seem to further induce medical school-related stress and anxiety. Combined group and individual resource-oriented coaching early in medical education might reduce examination-related stress and anxiety and, consequently, enhance academic performance. Good quality evidence, however, remains scarce. In this study, therefore, we explored the question of whether coaching affects examination-related stress and health in medical students.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial. Students who registered for the first medical academic examination in August 2014 at the University of Lübeck were recruited and randomized into three groups. The intervention groups 1 and 2 received a 1-hour psychoeducative seminar. Group 1 additionally received two 1-hour sessions of individual coaching during examination preparation. Group 3 served as a control group. We compared changes in self-rated general health (measured by a single item), anxiety and depression (measured by the hospital anxiety and depression scale), as well as medical school stress (measured by the perceived medical school stress instrument). In order to further investigate the influence of group allocation on perceived medical school stress, we conducted a linear regression analysis.

Results

We saw a significant deterioration of general health and an increase in anxiety and depression scores in medical students while preparing for an examination. We found a small, but statistically significant, effect of group allocation on the development of perceived medical school stress. However, we could not differentiate between the effects of group coaching only and group coaching in combination with two sessions of individual coaching.

Conclusion

The health of medical students deteriorated while preparing for an examination. Short-term resource-oriented coaching might be an effective means of reducing medical school stress in candidates preparing for an examination.

Introduction

There is ample evidence that the years spent in acquiring medical education is a stressful and difficult period in the life of many students.Citation1 Starting at a good level,Citation2 the health and well-being of medical students seems to deteriorate throughout their education,Citation3 resulting in high rates of, for example, burnout and depression by the time of graduationCitation4 and residency.Citation5,Citation6 Burnt out medical students and residents, however, seem less likely to be(come) empathetic and productive physicians.Citation7,Citation8 In addition to the individual burden, it is thus considered a systemic problem.Citation9

Academic examinations seem to further provoke medical school-related stress and anxiety.Citation10 Leading to a vicious circle, examination-related stress and anxiety may impair the academic performance of susceptible future doctors.Citation11 There is evidence that female medical students are more prone to examination-related stress and anxiety.Citation12,Citation13 Since in many countries, to date, the majority of medical students are females; this finding is particularly important.Citation14 The large amount of content to be learnt for an examination, the self-expectation to perform well, concern about poor marks, the long duration of periods of assessment, and a lack of exercise are among other factors associated with examination-related stress and anxiety.Citation15,Citation16

In her meta-analysis of the results of anxiety-reduction programs, ErgeneCitation17 concluded that: “individually conducted programs, along with programs that combined individual and group counseling formats, produced the greatest changes”. In order to break the vicious circle of examination-related stress and anxiety, and impaired academic performance early in medical education, combined group and individual resource-oriented coaching may pose a promising solution.Citation18,Citation19 Shiralkar et al conclude in their systematic review of stress management programs for medical students that more methodological rigor is required for related studies in order to more precisely identify which elements of such programs might be the most promising.Citation20

Therefore, we explored the following questions by means of a randomized controlled trial:

Does resource-oriented coaching influence examination-related stress in medical students?

Does resource-oriented coaching influence general and mental health of medical students preparing for examination?

Materials and methods

We conducted a three-armed randomized controlled trial.

Participant recruitment and setting

All students who registered for the first medical examination in August 2014 at the University of Lübeck, a small public university with a focus on medicine and life sciences, were eligible to participate. We approached potentially eligible students in an anatomy refresher (“Anatomy in 5 days”Citation21) in the middle of the summer semester. Students were preliminarily enrolled on a voluntary basis. Those who did not fulfill the criteria for registration for the first medical examination by mid-July, or refused to register for other reasons, were then excluded.

Interventions

Students in the intervention groups (groups 1 and 2) received a 1-hour psychoeducative seminar. During this seminar, a psychologist addressed issues, such as emotional reactions toward stressors, unconscious persistence of unprocessed negative emotions, and the relationship of the procession of stressful events and sleep. At the end of the seminar, all participants were surveyed using a paper–pencil questionnaire (t1).

Students in group 1 received two 1-hour sessions of manual-based individual coaching by trained psychologists and physicians within an interval of 2 weeks. The coaching was based on the so-called wingwave® (Besser Siegmund Institut, Hamburg, Germany) method. wingwave uses a finger-strength test derived from the Bi-Digital-O-Ring-Test for the determination of unconscious stressors following a standardized protocol.Citation22 In order to process identified stressors, elements of eye movement desensitization and reprocession, and neurolinguistic programming techniques were applied.Citation22,Citation23 In several sessions ahead of the study period, four experienced wingwave coaches developed coaching techniques specifically for medical students in the examination preparation phase and wrote a standardized manual. As this coaching was not primarily designed to identify and treat deficits but to foster individual stress-management resources (“resilience” as defined by Zautra et al),Citation24 we labeled the intervention “resource-oriented coaching”.Citation25 During the first coaching session, students in group 1 received a universal serial bus memory stick containing hemisphere-stimulating musicCitation26 and were instructed on how to use it.

Following the psychoeducative seminar, students in group 2 received a universal serial bus memory stick containing hemisphere-stimulating musicCitation26 and an instruction sheet explaining how to use it.

Students in groups 1 and 2 were instructed to listen to the 20-minute piece of electronic music twice daily, before and during learning.

Students in group 3 served as control subjects and did not receive any intervention (“treatment as usual”). They were surveyed at the time of the psychoeducative seminar using a web survey containing the same questions as the paper–pencil survey in the treatment groups (t1).

To reduce potential dropout rates, the participants received a book voucher worth 5 Euro per completed questionnaire.

Randomization and allocation concealment

After preliminary enrolment, we randomly allocated participants to the treatment (groups 1 and 2) or control group (group 3) using a computer-generated random numbers table (randomization 1). By inviting those participants in the treatment group to participate in the psychoeducative seminar (described earlier), the students were immediately informed of their allocation to either control or treatment group. In a second step, the participants in the treatment group were randomly allocated to treatment groups 1 and 2 (randomization 2). This allocation was concealed by means of sealed, opaque envelopes until the end of the psychoeducative seminar and the t1 survey.

The participants, coaches, and the involved researcher were not blinded hereafter.

Measures

In addition to the information gathered about participants’ age and sex, outcome measures were chosen that would capture the possible intervention effects on different aspects of psychological health, including perceived study stress, self-rated general health, and mental health.

Outcomes were measured at two different points in time (after randomization 1 and the 1-hour psychoeducative seminar but before the examination preparation phase [t1] and directly before the examination [t2]). All outcome measures were used in numerous studies among medical students, as recommended by Shiralkar et al.Citation20

Self-rated general health was measured by a single item (“How would you describe your health in general?”) to be answered on a five-point Likert scale from “very good” to “very poor”.Citation27 Single item self-rated health has been found to be a predictor for several health outcomes in previous studies, including mortality.Citation28

In order to measure mental health, we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).Citation29 The HADS was initially developed for clinical populations but has been widely used among students in general and medical students in particular.Citation2,Citation30,Citation31 It comprises 14 items for two subscales. Each of the two subscales relates to anxiety and depression, and consists of seven items, which obtain responses on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0= mostly, to 3= not at all. Possible subscale scores range from 0 to 21. We used the German version (HADS-D), published by Herrmann-Lingen et al in 1995 and available in the third edition.Citation32

We measured perceived medical school stress using the Perceived Medical School Stress (PMSS) scale in the German language (PMSS-D).Citation33 This instrument was originally developed by Vitaliano et al in 1984Citation34 and has been translated into different languages and cultures and comprises 13 items in the German version. Each item can be answered on a five-point Likert scale (1= I strongly disagree; 5= I strongly agree). PMSS results have been linked to physical and mental well-beingCitation33 and have predictive validity for mental health problems in medical professionals 4 years after graduation.Citation35 Shiralkar et al recommend using the PMSS as a standard measure for the evaluation of medical school stress management programs.Citation20

Additionally, we collected qualitative data using focus groups and qualitative interviews. The qualitative analyses were designed to gain insight into the effective constituents of the intervention and to ask about adverse events. These results will be published separately.

Planned sample size

With 39 students per group, the trial would have been powered to detect medium-to-large effect sizes (d=0.65) for the difference in PMSS (standard deviation [SD] 7.8),Citation33 using a two-tailed test, α =0.05 and an 80% power level. This number was determined using G*Power.Citation36 In order to allow for a 10% dropout, the target sample size for the trial was 43 students per group (intervention groups 1 and 2 and control group 3).

Statistical methods

We substituted missing values following the rules provided in the handbooks for the instruments, that is, through interpolation where tolerable. We then excluded incomplete data sets. After a plausibility check, cases from the t1 and t2 surveys were matched using a self-generated pseudonym. We then excluded incomplete data sets. Data were missing from the responses of five students in the intervention group and seven in the control group, respectively. The last-observation-carried-forward method of imputation was chosen because this is a conservative method used in instances in which there is an equal dropout rate in the intervention and the control group.Citation37 Intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses yielded very similar results and we therefore present only the former. We used two-tailed t-tests to compare means of continuous variables. Where the assumptions for parametric tests were violated, we used the Mann–Whitney U tests. Results are reported as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Cohen’s d was used to calculate the size of the treatment effect. We considered values of 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, and 0.8 large effect sizes. For methodological characteristics of the linear regression analysis, see the respective subsection of the “Results” section. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical considerations

This trial is reported following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials criteria.Citation38 The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck (File reference 14-098) and registered with the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00006349) before the time of first participant enrolment.Citation39 All participants provided written informed consent.

Deviations from the trial protocol

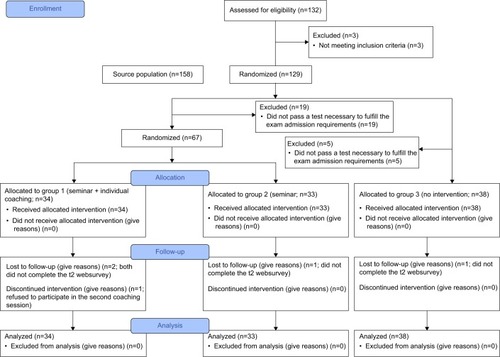

Due of an unexpected shortfall in the sample size (n=24 students did not pass a test necessary to fulfill the examination admission requirements, ), we decided to combine both intervention groups for the quantitative analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

displays baseline characteristics for all participants included. Overall, 35 male and 70 female students (M =24.2 years, SD =2.6) with an age range between 19 and 32 years participated in this study (66% of the whole class). The study participants were 0.5 years younger and the percentage of females was higher when compared to the whole class. We had a lower percentage of male participants in the coaching group and participants in this group were 0.5 years older (). The participant flow for the trial is shown in .

Table 1 Baseline sociodemographic characteristics

Outcomes

For the whole study population, regardless of allocation to treatment or control, we saw a statistically significant deterioration of general health (1.99 to 2.36; P<0.01) with a medium effect size (d=−0.64) between t1 and t2 (). Also for the whole group, we saw statistically significant increases of depression (3.94 to 5.23; P<0.01; d=0.47) and anxiety (7.75 to 8.96; P<0.01; d=0.33) levels during this period. Perceived medical school stress remained at about the same level in the whole study population (29.29 to 29.17, P=0.75).

Table 2 Outcomes

For the development of general health, depression and anxiety during the study period, we found no statistically significant differences between the groups. However, perceived medical school stress decreased in the coaching group (from 29.60 to 28.96; Δ=−0.64) and increased in the control group (from 28.74 to 29.55; Δ=0.82). This difference is statistically significant (P<0.05), yet the effect size is small (d=−0.21).

Linear regression analysis

In order to further investigate the influence of group allocation on the PMSS score, we conducted a linear regression analysis controlling for sex, age, and the PMSS t1 sum score. We built the model by stepwise forward inclusion with a criterion of P<0.05 for the inclusion and P>0.10 for the exclusion of effects.

Linear regression confirmed group allocation to be a statistically significant predictor of perceived medical school stress immediately prior to the first medical examination ().

Table 3 Linear regression analysis

Discussion

The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to investigate the efficacy of short-term individual resource-oriented coaching on examination-related stress. We found a small, but statistically significant effect on the development of perceived medical school stress in the coaching group(s). However, due to the shortfall in the number of participants, we are not able to differentiate between the effects of group coaching only versus group coaching accompanied by two sessions of individual coaching.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate not only the efficacy of resource-oriented coaching in the preparation phase before a medical academic examination, but also, at the same time, to take a closer look at the development of general and mental health while preparing for the examination.

For the whole study population, regardless of allocation to treatment or not, we saw a deterioration of general health and a rise of depression and anxiety levels during a relatively short time period of just over 3 weeks. Perceived medical school stress did not increase in the whole study population, which might have been caused by the identified effect of coaching on this variable, since it did increase in the control group (P=0.14, ). These observational findings show the significant level of stress induced by examination has a measurable negative impact on not only the mental, but also the general health of the medical students. Examination stress has been identified as an important reason for the deterioration of medical students’ health throughout their education.Citation10 Reducing the number of examinations and enhancing their design in order to mainly test knowledge and not primarily induce stress might thus be a promising starting point for health promotion in medical school students.Citation40

When looking at the development of perceived medical school stress more closely, we saw a statistically significant difference between the t2−t1 Δ of the groups and a similar significant prediction of the PMSS t2-score by group allocation. Given the small effect size and absolute differences, we have to interpret this finding with caution. What we can say is that it might indicate the efficacy of a resource-oriented coaching program for candidates preparing for medical academic examination. This has been shown to be the case for other stress management techniques in a number of quantitative and qualitative studies.Citation41–Citation43 However, it remains unclear whether the stress-reducing efficacy of the interventions employed in this and other studies stems from certain methodological components or it can merely be seen as an unspecific effect of support during the examination preparation phase.

Strengths and limitations

Unfortunately, due to a merging of the intended two coaching groups, we were not able to decide whether group coaching alone or group coaching combined with sessions of individual coaching is the more promising approach to reduce perceived medical school stress while preparing for examination. Also, as group allocation was not concealed; t1 measures were completed after randomization; and the students, coaches, and investigators were not blinded, the differences between the groups at both t1 and t2 might have been influenced by a certain amount of frustration in the control group in not having received coaching. The 1-hour psychoeducative seminar might also have had an influence on the intervention groups’ t1 score. However, we did not find any statistically significant differences between the groups at t1. Furthermore, it seems less likely that surveying the intervention group after the seminar led to an overestimation of the observed effect (or type I error) compared with an underestimation (or type II error). The randomized controlled design of our study can, nevertheless, be seen as a major strength when compared to other existing studies in this field, which are preponderantly nonrandomized and do not include control groups at all.Citation20,Citation44 The risk of selection bias can hence be estimated as low. Outcomes were determined in the same way in all groups bearing a low risk of social desirability by using a web survey completed at home.Citation45 The low dropout rate makes attrition bias due to incomplete outcome data unlikely.

Implications for research and practice

Future studies in this setting have to be designed to anticipate a higher dropout rate in order to avoid any power problems. Avoiding potential frustration through not receiving an intervention might be possible by employing a waiting-list-control design. It might prove helpful to identify students “in need of coaching” and recruit them for future, similar studies in order to depict a more realistic scenario (as students without a subjective need are less likely to benefit from such an intervention). In order to identify method-specific effects, and especially effective components of stress management programs, comparative mixed methods studies employing different kinds of interventions are required.

Our results show an urgent need for accompanying health promoting measures during the medical academic examination preparation phase. This should be of interest to universities in order for them to help prevent any avoidable examination-related health deterioration by paying for, or at least subsiding, appropriate measures, including, for example, individual short-term resource-oriented coaching as used in our study.

Conclusion

We saw a significant deterioration of general health and increasing anxiety and depression scores in medical students while preparing for examination. Our findings point to short-term resource-oriented coaching being effective in reducing medical school-stress in candidates preparing for examination, whereas the stress level increased in control subjects.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Cora Besser-Siegmund, Harry Siegmund, and Gabi Ertel for being a great coaching team and Sophia-Marie Saftien for her superb help during the coaching days. We also wish to thank the Lübeck Medical School, especially Jürgen Westermann, for supporting and funding this study. We would like to thank Angelika and Michael Hüppe for their input regarding design and analysis questions.

Disclosure

FN is a certified wingwave® coach and acted as one of the coaches in the present study. The authors declare no additional conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DyrbyeLNThomasMRShanafeltTDSystematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical studentsAcad Med200681435437316565188

- KötterTTautphäusYSchererMVoltmerEHealth-promoting factors in medical students and students of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: design and baseline results of a comparative longitudinal studyBMC Med Educ201414135

- VoltmerEKötterTSpahnCPerceived medical school stress and the development of behavior and experience patterns in German medical studentsMed Teach2012341084084722917267

- Koehl-HackertNSchultzJ-HNikendeiCMöltnerAGedroseBvan den BusscheHJüngerJBelastet in den Beruf – Empathie und Burnout bei Medizinstudierenden am Ende des Praktischen Jahres [Burdened into the job – final-year students’ empathy and burnout]Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes2012106211612422480895

- GoldhagenBEKingsolverKStinnettSSRosdahlJAStress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience trainingAdv Med Educ Pract2015652553226347361

- MataDARamosMABansalNPrevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysisJAMA2015314222373238326647259

- WallaceJELemaireJBGhaliWAPhysician wellness: a missing quality indicatorLancet200937497021714172119914516

- DewaCSLoongDBonatoSThanhNXJacobsPHow does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature reviewBMC Health Serv Res20141432525066375

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)Physician burnout (position paper) – AAFP policies Available from: http://bit.ly/1CcVG09Accessed August 2, 2016

- LyndonMPStromJMAlyamiHMThe relationship between academic assessment and psychological distress among medical students: a systematic reviewPerspect Med Educ20143640541825428333

- FriersonHTHobanJDThe effects of acute test anxiety on NBME Part I performanceJ Natl Med Assoc19928486866891507259

- FarooqiYNGhaniRSpielbergerCDGender differences in test anxiety and academic performance of medical studentsInt J Psychol Behav Sci2012223843

- Colbert-GetzJMFleishmanCJungJShilkofskiNHow do gender and anxiety affect students’ self-assessment and actual performance on a high-stakes clinical skills examination?Acad Med2013881444823165273

- General Medical CouncilThe state of medical education and practice in the UK report2014 Available from: http://bit.ly/1zYDJTKAccessed August 2, 2016

- HashmatSHashmatMAmanullahFAzizSFactors causing exam anxiety in medical studentsJ Pak Med Assoc200858416717018655422

- YusoffMSAssociations of pass-fail outcomes with psychological health of first-year medical students in a Malaysian medical schoolSultan Qaboos Univ Med J201313110711423573390

- ErgeneTEffective interventions on test anxiety reduction a meta-analysisSchool Psychol Int2003243313328

- GaleACGilbertJWatsonALife coaching to manage trainee under-performanceMed Educ201448553924712960

- WildKScholzMRopohlABräuerLPaulsenFBurgerPHMStrategies against burnout and anxiety in medical education – implementation and evaluation of a new course on relaxation techniques (Relacs) for medical studentsPLoS One2014912e11496725517399

- ShiralkarMTHarrisTBEddins-FolensbeeFFCoverdaleJHA systematic review of stress-management programs for medical studentsAcad Psychiatry201337315816423446664

- GebertAAl-SamirKWestermannJWie kann die Effizienz der Examensvorbereitung im Medizinstudium verbessert werden? Analyse eines Anatomierepetitoriums über drei Jahre [How to improve the efficiency of exam preparation in the study of medicine? Analysis of a repetition course in anatomy during three years]Med Ausbild2002193537

- RathschlagMMemmertDReducing anxiety and enhancing physical performance by using an advanced version of EMDR: a pilot studyBrain Behav20144334835524944864

- Besser-SiegmundCSiegmundHAchieve success through wingwave coaching Available from: http://bit.ly/1zKhS19Accessed August 2, 2016

- ZautraAJHallJSMurrayKEResilience – a new definition of health for people and communitiesHandbook of Adult ResilienceNew York, NYGuilford Publications201247

- World Health OrganizationOttawa Charter for Health PromotionGenevaWHO1986 Available from: http://bit.ly/1uBBtiyAccessed August 2, 2016

- Walk at the beach Available from: http://bit.ly/1WmTJtWAccessed August 2, 2016

- World Health OrganizationHealth Interview Surveys. Towards International HarmonizationGenevaWHO Available from: http://bit.ly/1uIUvleAccessed August 2, 2016

- DeSalvoKBBloserNReynoldsKHeJMuntnerPMortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med200621326727516336622

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- WoolfKCaveJMcManusICDacreJE“It gives you an understanding you can’t get from any book”. The relationship between medical students’ and doctors’ personal illness experiences and their performance: a qualitative and quantitative studyBMC Med Educ2007750

- QuinceTAWoodDFParkerRABensonJPrevalence and persistence of depression among undergraduate medical students: a longitudinal study at one UK medical schoolBMJ Open201224 pii:e001519

- Herrmann-LingenCBussUSnaithRPHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Deutsche Version3 AuflageBernHuber2011

- KötterTVoltmerEMeasurement of specific medical school stress: translation of the “perceived medical school stress instrument” to the German languageGMS Z Med Ausbild2013302Doc2223737919

- VitalianoPPRussoJCarrJEHeerwagenJHMedical school pressures and their relationship to anxietyJ Nerv Ment Dis1984172127307366502152

- Chew-GrahamCARogersAYassinN“I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records”: medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problemsMed Educ2003371087388012974841

- FaulFErdfelderELangAGBuchnerAG*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciencesBehav Res Methods200739217519117695343

- LanePHandling drop-out in longitudinal clinical trials: a comparison of the LOCF and MMRM approachesPharm Stat2008729310617351897

- MoherDHopewellSSchulzKFCONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trialsJ Clin Epidemiol2010638e13720346624

- KötterTIndividual short-term coaching against exam-related stress – trial registry entry Available from: http://bit.ly/1GxnsZsAccessed August 2, 2016

- KötterTPohontschNJVoltmerEStressors and starting points for health-promoting interventions in medical school from the students’ perspective: a qualitative studyPerspect Med Educ20154312813526032519

- SimardAAHenryMImpact of a short yoga intervention on medical students’ health: a pilot studyMed Teach2009311095095219877871

- DayalanHSubramanianSElangoTPsychological well-being in medical students during exam stress-influence of short-term practice of mind sound technologyIndian J Med Sci2010641150150723051942

- PereiraMABarbosaMATeaching strategies for coping with stress – the perceptions of medical studentsBMC Med Educ20131315023565944

- ShapiroSLShapiroDESchwartzGEStress management in medical education: a review of the literatureAcad Med200075774875910926029

- JoinsonASocial desirability, anonymity, and Internet-based questionnairesBehav Res Methods Instrum Comput199931343343810502866