Abstract

Background

Food allergy is an increasing public health burden, and is considered among the most common chronic noncommunicable diseases in children. Proper diagnosis and management of food allergy by a health care provider is crucial in keeping affected children safe while simultaneously averting unnecessary avoidance.

Objective

The rationale of the study was to estimate the knowledge of pediatric residents and academic general pediatric fellows with regard to food allergies in children.

Methods

A cross-sectional and prospective study was carried out at Hamad Medical Corporation, the only tertiary care, academic and teaching hospital in the State of Qatar. The study took place between January 1, 2015 and September 30, 2015.

Results

Out of the 68 questionnaires distributed, 68 (100%) were returned by the end of the study. Among the participants, 15 (22%) were in post-graduate year-1 (PGY-1), 16 (23.5%) in PGY-2, 17 (25%) in PGY-3, 12 (16%) in PGY-4, and 8 (12%) were academic general pediatric fellows. Our trainees answered 60.14% of knowledge based questions correctly. In the section of treatment and management of food allergy in childhood, 23 (34%) of respondents’ main concern when taking care of a patient with food allergies was making sure the patient is not exposed to food allergen, while 22 (33%) reported no concerns. In the section of treatment and management of food allergy in childhood, 22 (33%) of participants reported no concerns in taking care of a child with food allergy, while 23 (34%) of respondents’ main concern was making sure the patient is not exposed to food allergen. In the teaching and training section, 56% of participants stated that they have not received formal education on how to recognize and treat food allergies, while 59% claimed not being trained on how to administer injectable epinephrine. Furthermore, approximately 60% of all participants expressed the need of additional information about recognizing and treating food allergies and recommended certification and regulation of food allergy training for all residents.

Conclusion

There is an appreciable lack of knowledge in identifying food allergy and managing anaphylaxis reaction in children, among pediatric residents. Robust efforts should be implemented by attending immunologists to improve the lack of knowledge and improve the trainee’s confidence when facing such cases.

Introduction

Food allergy is an increasing public health burden, and is considered among the most common chronic noncommunicable diseases in children.Citation1,Citation2 Almost 25% of individuals residing in the US perceive having food allergy, while in fact only 8% of children and 4% of teens and adults have genuine immunoglobulin E-mediated food reactions.Citation3 The Center for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that food allergies among children have augmented from 3.5% to 4.6% between 1997 and 2011.Citation4 More recent surveys have shown that almost 10% of preschool children suffer from clinical food allergy. Moreover, in rapidly developing countries, such as China, the prevalence of clinical food allergy is around 7% in preschoolers.Citation2

Food allergy is associated with a range of skin manifestations such as dermatitis, urticaria, eczema, angioedema, and itching. It also presents with gastrointestinal tract changes such as abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In addition, food allergy manifests with respiratory illnesses, such as asthma and laryngeal edema.Citation5 Anaphylactic shock due to food allergy is the most serious outcome and can lead to death if immediate treatment is not administered.Citation6 The most common food allergens that affect children are cow’s milk, eggs, wheat, soy and peanuts. Meanwhile, tree nuts, fish, lobster, crab, and shrimp cause allergy more commonly among adults.Citation5,Citation7 There is no known cure for food allergies; however, absolute avoidance of food allergens and early recognition and management of allergic reactions to food are crucial measures to evade dreadful health consequences.Citation8 Speedy administration (within a few minutes of anaphylaxis) of epinephrine is critically important to manage anaphylaxis properly.Citation9

Approximately 20% of children with food allergies have had a reaction from accidentally ingesting food allergens during school hours.Citation10,Citation11 Moreover, 25% of the severe and potentially life-threatening reactions (anaphylaxis) noted in schools occurred in children with no previous diagnosis of food allergy.Citation10,Citation12

Proper diagnosis and management of food allergy by a health care provider is crucial in keeping affected children safe while simultaneously averting unnecessary avoidance.Citation13 Since primary care providers are usually the first and perhaps the only physicians these children encounter, it is important that they supply parents or caregivers with conceivably lifesaving medications and provide proper education on how to identify and react to allergic reactions.Citation14 Studies have shown that pediatricians adhere poorly to food allergy guidelines. This could be due to pediatricians’ deficiency of familiarity with the guidelines, and their accuracy concerning their role in managing food allergy.Citation15

Given the increasing concern of food allergies and the crucial role of the primary care physician in its diagnosis and management, the rationale of this study was to estimate the knowledge and attitudes of our postgraduate pediatric physicians regarding food allergies.

Methods

A cross-sectional and prospective study was carried out at Hamad Medical Corporation, the only tertiary care, academic and teaching hospital in the State of Qatar. The study took place between January 1, 2015 and September 30, 2015. A total of 68 postgraduate pediatric physicians were targeted. In all, 68 eligible physicians were included in the study.

A self-administered questionnaire was handed out on-site during working hours to all pediatric residents and academic general pediatric fellows and was returned by the participants to a specified box. Verbal consent was attained prior to administering the questionnaire, and physicians were informed of why the information was being collected and how it would be used. Before distributing the questionnaire, a statement was read to participants briefing them that their participation was voluntary and assured that their answers would remain anonymous and confidential. There was no incentive for physicians to participate, and we did not provide any reminders. Approval for the study was obtained from Hamad Medical Corporation-Ethics Committee (reference no. MRC/0302/2015).

The questionnaire was composed of four sections and a total of 26 items, and its content was based on previous surveys,Citation16–Citation18 but customized to fit our system. These sections addressed physicians’ knowledge of food allergy as well as treatment, management, teaching, and training in regard to the disease.

The questionnaire was divided as follows:

Sociodemographic data: two questions

Knowledge: nine questions

Treatments and management: two questions

Teaching and training: 12 questions

At the end of the questionnaire, we provided an empty space for any comments.

The answers to questions asked to physicians were of multiple-choice type: “yes”, “no”, “not sure”; “true”, “false”, “not sure”, and a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “very uncomfortable” to “very comfortable”.

We used descriptive statistics as well as percentages to summarize demographics and all other items. All statistical analyses were done using statistical package SPSS, version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

All the 68 (100%) questionnaires distributed were returned by the end of the study. The ratio of female to male was 1.5:1. Among the participants, 15 (22%) were in postgraduate year (PGY) 1, 16 (23.5%) in PGY-2, 17 (25%) in PGY-3, 12 (18%) in PGY-4, and eight (12%) were general pediatric fellows.

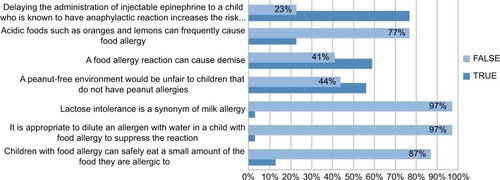

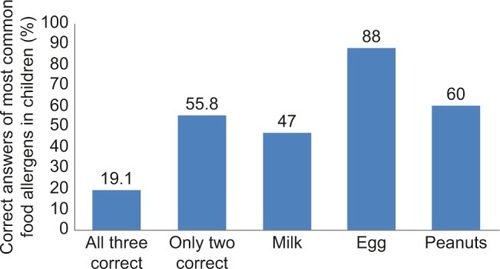

Our trainees answered 60.14% of knowledge-based questions correctly. Variation in food allergy knowledge was noticed in each content field ( and ).

Figure 1 Physicians were asked which of the following are the three most common food allergens in children.

In the section on treatment and management of food allergy in childhood (), 22 (33%) participants reported no concerns in taking care of a child with food allergy, while 23 (34%) respondents’ main concern was making sure that the patient is not exposed to the food allergen. Moreover, when asked what other additional restrictions are required in a child with food allergy, one half of participants answered reading labels, followed by “nothing” (18%), measles/mumps/rubella and influenza vaccines for egg allergy (16%), healthy food (7%), vegetarian diet (7%), and low fat (6%).

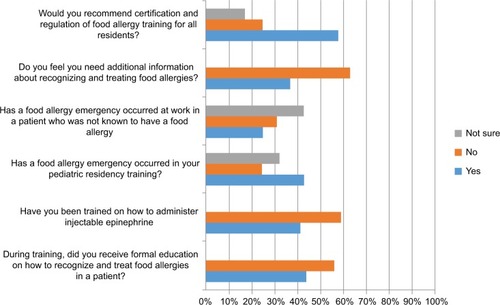

In the teaching and training section, 56% of participants stated that they have not received formal education on how to recognize and treat food allergies, while 59% claimed not being trained on how to administer injectable epinephrine. In addition, only 43% of the trainees stated that they have witnessed food allergy emergency during their pediatric residency training. Furthermore, approximately 60% of all participants expressed the need of additional information about recognizing and treating food allergies and recommended certification and regulation of food allergy training for all residents. Participants were also asked to list the main topics in food allergies needed to be mastered. Sixty percent of trainees required more information regarding epinephrine auto-injector administration, followed by 50% requesting information of how to counsel parents about food allergy, and 45% wanted more literature on how to recognize signs and symptoms of food allergy and anaphylaxis. Answers to questions related to the comfort level in dealing with patients who have food allergy were well distributed across a five-point Likert scale, ranging from very uncomfortable to very comfortable ().

Table 1 Answers related to level of comfort in dealing with food allergy cases

Finally, there was no statistical significance (P>0.05) of correct answers in the sections related to knowledge, management, and teaching and training across all levels of pediatric trainees.

Discussion

Our study has shown that there is a deficiency in knowledge of food allergy as well as treatment, management, teaching, and training in regard to the disease among pediatric physicians in training. This study is the first to supply a comprehensive review of food allergy knowledge and perceptions among pediatric physicians in training in the State of Qatar.

It should be noted that only 5% of participants felt very comfortable in caring for a patient with a food allergy, while barely 20% of respondents correctly identified milk, egg, and peanuts as the three most common food allergens in children. Strikingly, only one in four physicians agreed that food allergy can cause anaphylactic shock and death. However, more than three-quarters of the participants recognized the importance of timely administration of epinephrine.

A few authors have studied perception, knowledge, and management of food allergies among physicians. For instance, a study conducted by Wang et alCitation19 on primary care physicians’ approach to food-induced anaphylaxis showed that residents and fellows were more capable of identifying and managing food allergy reactions with adrenaline than attending physicians. A different study conducted by Krugman et alCitation20 has shown that pediatricians were incompletely educated to recognize and treat anaphylaxis due to food allergy. The investigators advised that the decreasing opportunity to choose subspecialty elective rotations during residency was the main culprit in deficiency in knowledge as well as management of anaphylaxis in new graduates. Furthermore, Klemans et alCitation21 investigated the management of food allergic reactions by general practitioners. The study showed that management choice was dependent on the severity of the reaction (mild vs. anaphylaxis, P<0.001). Nevertheless, epinephrine was used for management of anaphylaxis with predominantly respiratory symptoms in only 27% of participants and for anaphylaxis with primarily cardiovascular manifestations in 73%.

A study conducted by Gupta et alCitation18 on food allergy knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in 407 pediatricians and primary care physicians showed that doctors’ overall knowledge was average, and fewer than 30% of the respondents felt comfortable in taking care of children with food allergies.

Physicians usually report lack of proper training in the care of children with food allergy leading to hesitance in managing the disease.Citation22 This was echoed by our participants where 60% of physicians who were surveyed acknowledged the need for more training regarding management of children with food allergies. Through their comments, it is obvious that participants require supplementary educational means and certificates for food allergy training.

Studies have shown that a large proportion of primary care physicians in the US are not supplying patients with the modes to properly manage food-induced reactions.Citation16,Citation22–Citation24 Amid the augmentation of prevalence in food allergy and its often serious complications, it is crucial for primary care physicians to be familiarized about this condition. A study conducted by Baptist and Baldwin showed that physicians who rotated under the allergy/immunology services during their training years were more comfortable with common allergic disorders than those who did not select the rotation.Citation25

A critical point in our study was that the percentage of correct answers did not improve with higher level of training. Our program despite being located in the Middle East is accredited by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education-International, and hence, our results could be similar if conducted in the US.

Food allergy education resources have been refined for generalists;Citation26 however, work is required to boost the dissemination and use of these resources to better prepare primary care physicians to meet the needs of their food allergic patients. Acquaintance with available resources is the initial step in enhancing physicians’ knowledge and confidence in managing food allergy.

Restriction of duty hours was one of the obstacles that we faced when trying to make the allergy/immunology rotation as a core or selective rotation in the residency program. In order to cover the gap in knowledge among trainees, the first author of this manuscript started the Allergy and Immunology Awareness program (AIAP), with a main aim to create educational materials for patients and their families as well as doctors, nurses, and other health care providers related to allergy and immunology. The AIAP has produced around 20 publications in the last 2 years (http://aiap.hamad.qa), two of which were handed to residents and fellows to improve their knowledge of food allergy in children.

One of the strengths of our study is that our results can be implemented in many countries, while a limitation is that our data could have been more appealing if we could have compared the knowledge and attitudes of pediatric trainees before and after an allergy rotation.

Conclusion

There is an appreciable lack of knowledge in identifying food allergy and managing anaphylaxis reaction in children, among pediatric residents. Pediatric residency working hours’ rule impedes the option of having an allergy/immunology rotation during residency. Robust efforts should be implemented by attending immunologists to improve the lack of knowledge and improve the trainee’s confidence when facing such cases. This can be accomplished by implementing an allergy/immunology rotation to all pediatric trainees, and by introducing simple food allergy guidelines.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors researched the data, designed the structure, wrote the first draft, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Medical Research Center in Hamad Medical Corporation for their support and ethical approval.

Disclosure

The abstract of this paper was presented at the session 520 at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Annual Meeting on March 4–7, 2016, in Los Angeles, CA, with interim findings. The abstract was published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, February 2016, Volume 137, Issue 2, Supplement, page AB159. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BranumAMLukacsSLFood allergy among U.S. children: trends in prevalence and hospitalizationsNCHS Data Brief20081018

- PrescottSLPawankarRAllenKJA global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in childrenWorld Allergy Organ J2013612124304599

- American College of Allergy, Asthma, & ImmunologyFood allergy: a practice parameterAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2006963 Suppl 2S1S6816597066

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionQuickStats: percentage of children aged <18 years with food, skin, or hay fever/respiratory allergies – National Health Interview Survey, United States, 1998–20092011 Available from: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6011a7.htm?s_cid+mm6011a7_wAccessed October 12, 2015

- TaylorSLHefleSLFood allergies and other food sensitivitiesFood Technol20015596883

- SampsonHAMuñoz-FurlongACampbellRLSecond symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report–second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposiumAnn Emerg Med200647437338016546624

- AhnKFood allergy: diagnosis and managementKorean J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol2011313163169

- Food allergies: What you need to know [webpage on the Internet]Silver Spring, MDU.S. Food and Drug Administration2016 [updated 24/05/2016]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPack-agingLabeling/FoodAllergens/ucm079311.htmAccessed October 8, 2016

- Joint Task Force on Practice ParametersAmerican Academy of Allergy, Asthma and ImmunologyAmerican College of Allergy, Asthma and ImmunologyJoint Council of Allergy, Asthma and ImmunologyThe diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: an updated practice parameterJ Allergy Clin Immunol20051153 Suppl 2S483S52315753926

- SichererSHFurlongTJDeSimoneJSampsonHAThe US Peanut and Tree Nut Allergy Registry: characteristics of reactions in schools and day careJ Pediatr2001138456056511295721

- Nowak-WegrzynAConover-WalkerMKWoodRAFood-allergic reactions in schools and preschoolsArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2001155779079511434845

- McIntyreCLSheetzAHCarrollCRYoungMCAdministration of epinephrine for life-threatening allergic reactions in school settingsPediatrics200511651134114016264000

- GuptaRSSpringstonEEWarrierMRThe prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United StatesPediatrics2011128e9e1721690110

- NIAID-Sponsored Expert PanelBoyceJAAssa’adABurksAWGuidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert PanelJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101266 SupplS1S5821134576

- GuptaRSLauCHDyerAAFood allergy diagnosis and management practices among pediatriciansClin Pediatr (Phila)201453652453024419266

- CruzNVWilsonBGFiocchiABahnaSLAmerican College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Adverse Reactions to Food CommitteeSurvey of physicians’ approach to food allergy, Part 1: prevalence and manifestationsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200799432533317941279

- GreiweJCPazheriFSchroerBNannies’ knowledge, attitude, and management of food allergies of children: an online surveyJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract201531636725577620

- GuptaRSSpringstonEEKimJSFood allergy knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of primary care physiciansPediatrics2010125112613219969619

- WangJSichererSHNowak-WegrzynAPrimary care physicians’ approach to food-induced anaphylaxis: a surveyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2004114368969115446292

- KrugmanSDChiaramonteDRMatsuiECDiagnosis and management of food-induced anaphylaxis: a national survey of pediatriciansPediatrics20061183e554e56016950947

- KlemansRJLeTMSigurdssonVManagement of acute food allergic reactions by general practitionersEur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol2013452435123821832

- WilsonBGCruzNVFiocchiABahnaSLAmerican College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Adverse Reactions to Food CommitteeSurvey of physicians’ approach to food allergy. Part 2: allergens, diagnosis, treatment, and preventionSchool Nurse News20082551415

- GuptaRSSpringstonEESmithBPongracicJHollJLWarrierMRParent report of physician diagnosis in pediatric food allergyJ Allergy Clin Immunol2013131115015622947345

- SichererSHFormanJANooneSAUse assessment of self-administered epinephrine among food-allergic children and pediatriciansPediatrics2000105235936210654956

- BaptistAPBaldwinJLPhysician attitudes, opinions, and referral patterns: comparisons of those who have and have not taken an allergy/immunology rotationAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200493322723115478380

- YuJEKumarABruhnCTeuberSSSichererSHDevelopment of a food allergy education resource for primary care physiciansBMC Med Educ200884518826650