Abstract

Medical school mentoring programs incorporate a wide range of objectives. Clinical mentoring programs help to develop students’ clinical skills and can increase interest in under-subscribed specialties. Those that focus on teaching professionalism are integrated into medical school curriculums in order to overcome the “hidden curriculum”. Positive mentoring plays a part in reversing the decline of academic medicine, by sparking interest through early research experiences. It also has an important role in encouraging recruitment of under-represented minority groups into the medical profession through widening access programs. The aim of our review of the literature, is to analyze current trends in medical student mentoring programs, taking into account their objectives, execution, and evaluation. We outline the challenges encountered, potential benefits, and key future implications for mentees, mentors, and institutions.

Introduction

The word “mentor” originates from Greek mid-eighteenth century, and in Homer’s epic, the Odyssey. It was the name of the friend Odysseus assigned as a trusted adviser to his son Telemachus in his absence. In the present day, the word can be used as a verb – “to advise or train”, or a noun defined as: “An experienced and trusted adviser” Citation1

In medical education, a mentor may have many roles, for example, supervisor, teacher, or a coach.Citation2 However, unlike teaching, mentoring involves developing a relationship that focuses on achieving specific goals.Citation3 A mentor is employed to counsel and teach a less experienced student or colleague, for example, in near-peer mentoring. The aim is to guide juniors to achieve a wide array of objectives, such as attainment of a practical skill, personal and professional development, research opportunity, and academic development.Citation3 Mentors also provide emotional support and counseling, as well as professional help.Citation4

A prominent review described five key elements to mentoring:Citation5

Should help the mentee to achieve short-and long-term goals.

Should include role modeling, and help with career development.

Both mentee and mentor should benefit from the relationship.

Relationships should involve direct interaction between mentor and mentee.

Mentors should be more experienced when compared with the mentee.

With increasing awareness of the potential value of mentoring, programs are now being established at medical schools worldwide. Through this literature review, we will summarize current insights in undergraduate medical mentoring programs, and highlight the key take-home messages, in order to guide institutions, mentors, and mentees in the future design and delivery of effective mentoring programs.

Methods

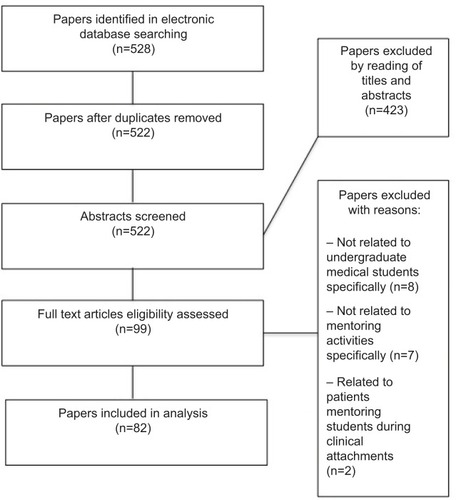

A database search was performed, including PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane in order to identify articles related to mentoring in undergraduate medical education. The keywords used alone and in combination were mentoring, mentoring programme, medical student, mentor, mentee, mentorship, undergraduate, peer mentoring, students as mentors, medical education and, medical school. The searches included articles published between 1990 and 2018 due to the broad scope of the topic, considering primary literature, reviews, commentaries, and case studies. In total, the searches fielded 528 articles. Two of the authors independently sorted the articles for those relevant to mentoring in medical schools. Duplicates were excluded (n=6), as well as a further 423 articles after reading titles and abstracts. Finally, the remaining 99 articles were assessed for eligibility and 17 were excluded because: patients carried out mentoring activities; or articles did not focus specifically on mentoring or undergraduate medical education. Of these, 82 articles were deemed appropriate and were included in this review. Searches were complete on the 12 February 2018 and the process demonstrating how articles were selected is shown in .

Mentor program objectives

Medical school mentoring programs are established worldwide, with varying aims and objectives. These were summarized by Frei et alCitation3 as follows: to increase interest in clinical specialties, to develop professionalism and personal growth, to promote interest in academic medicine, and to provide career counseling. In addition, mentoring is a key component of widening access programs that are often medical student led, and aim to increase applications to medicine from under-represented groups.

Clinical mentoring

Formally recognized supervisors are assigned to trainees at all stages of clinical training. This differs from mentors; who are more likely to be hand selected by mentees and with whom the relationship is more informal. Traditionally, supervisors ensure that trainees have sufficient evidence to progress through training, while the role of a mentor is to offer advice and guidance. However, the two are not mutually exclusive as a supervisor can act as a mentor, and vice versa.Citation6

A number of clinical mentoring initiatives have been specifically designed to prepare final-year medical students for working as a junior doctor.Citation7–Citation9 Recently qualified doctors act as mentors by facilitating clinical skills sessions, bedside teaching, and simulation. This can result in an increase in confidence and self-perceived preparedness for starting work as doctors and a reduction in the performance gap.Citation8,Citation9

Also, positive mentoring can have a significant influence on speciality choice.Citation10 Under-subscribed specialities use mentoring initiatives in the early years of medical school to increase exposure and generate interest. Early mentoring can offer students an insight into what it is like to work in that speciality and challenges preconceptions they may have.Citation11–Citation13 By increasing interaction between specialists and students, these initiatives facilitate learning through constructive feedback and career counseling.Citation14 This can encourage students to apply to particular specialties and provides them adequate time and guidance to begin preparing for the application process.Citation15 A study showed that students who undertook surgery-related research and developed mentor relationships in years 1 and 2 were significantly more likely to maintain an interest in surgical specialities later in their training.Citation16 However, we note the lack of studies identifying a causal relationship between early speciality mentoring and a direct increase in trainee applications. We acknowledge that such a study may not be possible due to a combination of factors affecting career choice, including ethnic, economic, and social influences.Citation10

Professionalism and personal development

As well as its influence on specialty recruitment, mentoring plays a role in student and trainee personal development and professionalism. Professionalism was not always an explicit part of the medical curriculum, and largely fell within the remit of the “hidden curriculum”. This has been defined as: “the context in which the formal curriculum is delivered, and comprises the norms, attitudes, and policies learners implicitly embrace”.Citation17 In other words, the hidden curriculum comprises the unintended lessons that are learned but not taught, and can support or contradict the formal, overt curriculum. Professionalism, in this way, was learned through socialization of the profession and upwards networking, as well as lessons learned in observing clinical teachers.

Nevertheless, over the last two decades, there have been increasing concerns regarding negative role modeling. This occurs when students witness unprofessional behavior in the clinical setting. A failure to address these issues formally can compound detrimental effects of such behavior and result in ethical erosion,Citation18 rather than enabling positive professional enculturation.Citation19

More recently, with increasing recognition that deliberate teaching alongside role-modeling is necessary to cultivate professionalism,Citation20 teaching and assessment of professionalism has now been integrated into formal medical school curricula in the UK and USA. Mentoring plays a key role in the teaching and assessment of professionalism in these curricula – an example is the “Professionalism and the Practice of Medicine (PPM)” course at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, implemented in 2001. Faculty mentors were introduced to assist and counsel students, as well as serving as role models. Assessment was undertaken through the presentation of a portfolio and self, peer, and mentor evaluation.Citation21

Ramani et al discussed the role of mentoring in the cultivation of medical student professional development.Citation22 They emphasize the importance of mentoring relationships and the need to balance support and challenge, noting: “If mentors are overly supportive without challenging mentees, the mentees do not grow professionally; on the other hand, challenging without supporting causes mentees to regress in their professional development”. Nevertheless, they acknowledge the limitation that faculty members do not always receive the training they may require to serve as effective mentors alongside their other core responsibilities.

Academic medicine and research

Around the world, academic medicine is in decline. In order to tackle this, a number of institutions, for example in the UK and Canada, have established academic training programs with an emphasis on university faculty mentoring trainees in research.Citation23

The opportunity for research involvement varies across medical schools, with some universities offering integrated PhD programs, and others introductory research components as part of their curriculum.Citation24 Furthermore, student engagement with research varies, and although some institutions have a high proportion of students involved in research,Citation25 it is more likely to be at research-elite universities, and students with research experience prior to commencing medical training.Citation26 Those at research-elite universities have a more satisfactory research training experience,Citation27 while their counterparts at other institutions may be more limited in the type of research they are able to conduct.Citation28

The aim of academic mentoring programs is to cultivate a positive attitude toward academia and enable mentees to tailor and apply research in ways that can benefit their future careers.Citation23,Citation27,Citation29 Trainees value programs taking a holistic approach, with clear pathways and flexibility, allowing them to move in and out of research at different stages of their careers.Citation30 Such programs expose trainees not only to research, but also other aspects of academic learning and personal and professional development, including teaching and the process of peer review.Citation31

Widening access

Over the last two decades, there has been increasing awareness of the lack of social diversity of students in the medical profession. Globally, women, ethnic minorities, and students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds are under- represented in the medical profession. Although gender disparity is reducing, with women now representing approximately half of medical students in the USA, they remain a minority within certain specialties, for example, general surgery.Citation32 There is a suggestion that same sex mentoring for female medics may be of benefit, with female students highly rating exposure to female mentors and organizations supporting women in surgery. However, as noted by O’Connor, in orthopedic surgery, only 14% of faculty and residents are women, as compared with other specialties, therefore, same gender mentorship opportunities are limited.Citation33 Furthermore, internal motivators can have a significant influence on career direction for female students, for example, the perception that specializing in orthopedic surgery may be detrimental to work/life balance.Citation34

Socioeconomic disparity is a major issue worldwide, including in the UK despite the introduction of several widening access foundation degree programs to medicine.Citation35,Citation36 A number of outreach medical student-led mentorship programs have been established worldwide, with the aim of increasing applicants from diverse, non-traditional backgrounds. Examples of two such programs are in Detroit, MI, USACitation37 and in the UK.Citation38 Both involve linking medical students with school students from under-represented minorities in order to foster an interest in a career in medicine and assist in providing work experience opportunities and experiential learning through summer schools and career counseling. Varying levels of success are reported with such programs for a number of reasons, in the case of the UK program, the majority of mentees were lost to follow-up. Nonetheless, feedback received from mentees annual evaluations was positive.

Medical students from under-represented minorities identify a lack of access to adequate mentoring when facing key career decisions, as a major issue and challenge. Freeman et al and Nicholson and Cleland explored how medical students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds perceived their own social capital, noting that these students struggled due to reduced awareness of the need for upwards networking in order to negotiate access to resources required to create capital.Citation39,Citation40 The authors recommended a system of peer mentorship for under-represented students with traditional, senior medical students, finding that this was able to facilitate the bridging of capital for both applicants and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Students as mentors (near-peer mentoring)

Generally, there are two scenarios where medical students act as mentors, when senior medical students mentor junior students and when medical students mentor school or college pupils applying to higher education.

A number of near-peer mentoring programs have been established, often in order to teach an aspect of the curriculum, such as a clinical or procedural skill. At one medical school, fifth-and sixth-year students train fourth-year students how to perform and interpret abdominal ultrasound scans. The skill is taught over three sessions, with both mentors and mentees reporting high satisfaction scores on completion of the program.Citation41 Senior medical students acting as mentors for junior students can also allow mentees to uncover the “hidden curriculum”, negotiate access to resources, and navigate aspects not formally covered in the medical school curriculum.Citation42 Nevertheless, not all medical students are suitable as mentors; those who are self-selecting or selected tend to be better than those randomly allocated.Citation43–Citation45 Moreover, students involved in mentoring require training, for example, in areas, such as giving constructive feedback and setting goals and expectations.Citation37,Citation43

Medical students involved in mentoring school pupils are able to provide an insight into life as a medical student, as well as support with the rigorous application process.Citation46 Moreover, those involved in widening access programs can also serve as role models and engage students who may previously have not considered a career in the medical profession.Citation37,Citation47,Citation48

Senior medical student mentors can bridge a gap between physicians and junior students. As student mentors and mentees are closer in terms of training, there is a more collaborative working environment and mentors are more able to relate to their mentees, and vice versa. This can enable mentees to gain a deeper understanding of challenging concepts that may otherwise be difficult to grasp.Citation41,Citation43,Citation49 Junior students may also be more comfortable raising areas of uncertainty with senior students, and a subsequent increase in knowledge, skills, and confidence can enhance their future interactions with clinicians.Citation44

Design and delivery of medical mentoring programs

The design and delivery of medical mentoring programs differ between medical schools, and programs are adapted to meet specific institutional or departmental requirements. Variables include mentee, mentor, and program characteristics.

Mentee characteristics

While some mentoring programs are designed for medical students in all years, others offer mentoring at a specific stage of training, such as preclinical or clinical years. Others focus on one particular year group, in order to provide students with skills that they will need in the near future. This is seen in UK mentoring programs for final-year students, which aim to prepare students for life as a newly qualified doctor and cover topics, including “how to clerk a patient” and “how to manage a ward round”.Citation7,Citation9

Programs involving all years are often primarily there to provide professional and pastoral support to students as they progress through medical school.Citation50,Citation51 Others offer clinical support to students during certain specialty rotations.Citation52,Citation53 There are also a number of programs that cater to groups of students possessing certain characteristics, for example, to mentor those struggling academically,Citation54 and support those from under-represented minority groups.Citation55 Widening access programs recruit mentees that meet specific criteria, usually taking into account socioeconomic background and attendance at schools in disadvantaged areas.Citation38,Citation45,Citation47

Methods to recruit mentees to programs are diverse and include the following: emails; flyers in the canteen; lecture shout-outs; social media advertising, and events, such as “mentor speed dating”.Citation8,Citation9,Citation12,Citation55,Citation56 Following recruitment, prospective mentees may be offered training,Citation57 and are usually given information on ground rules and expectations via email, lectures, or as a paper handout.Citation7,Citation9,Citation12,Citation56,Citation58–Citation61

Mentor characteristics

Mentors come from a range of backgrounds depending on the aim of the program, and can be residents, academic staff, faculty physicians, recently qualified doctors, speciality doctors, and senior medical students.Citation7,Citation29,Citation31,Citation62,Citation63 Many mentors put themselves forward for the role,Citation64 others are recommended or have demonstrated an interest in teaching or mentoring.Citation65,Citation66

Early career specialists with <10 years of experience can have a great impact on mentees, due to the fact that they are often more able to relate to students’ current personal and professional needs than more senior mentors, and likely to have more up-to-date information on the specialty application and interview process.Citation61,Citation67,Citation68 Likewise, doctors nearing retirement can also be highly valued as mentors due to their wealth of experience and reduced clinical workload, often allowing them to contribute more time to mentoring activities than their more junior counterparts.Citation69

Finally, there is variation as to whether mentors receive reimbursement for their role. In some programs, mentors are paid,Citation7,Citation52,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation63,Citation65 and less commonly, they are approved to use mentoring activities for academic promotion.Citation57,Citation65 Once appointed, most mentors receive some form of training, which can be provided face-to-face or online.Citation8,Citation12,Citation51,Citation52,Citation56,Citation70

Program characteristics

Medical school mentoring programs tend to be based on and modified from successful initiatives at other institutions, and further developed from mentee/mentor feedback.Citation50,Citation51,Citation65 Less often, a needs analysis is performed, or a program piloted prior to delivery;Citation8,Citation56,Citation67 which help to ensure that the program is designed adequately and effectively.

Programs may be funded by a range of sources, including the host university and/or third parties.Citation50,Citation51,Citation55,Citation56,Citation58,Citation61,Citation64,Citation66 Those that are funded are more likely to have dedicated admin support to help co-ordinate activitiesCitation12,Citation50,Citation55 and subsidize food and travel costs.Citation51,Citation55

Programs differ in the way mentors are assigned mentees. They can be randomly assigned,Citation57,Citation62,Citation63 or mentees can choose their own mentors, for example, via a mentor database.Citation9,Citation50,Citation56,Citation58,Citation71,Citation72 There are also online matching validated processes, such as electronic data processing (EDP)-supported matching procedures. Mentees and mentors complete online matching profiles consisting of questions that focus on professional orientation, work life priorities, and interests. An automated algorithm then provides matches depending on weighted correlated scores.Citation25 One study found no significant difference in satisfaction between personal and EDP-supported matching procedures and concluded that they could offer similar matching quality.Citation59 However, they suggested that offering a combination of matching methods is optimal, allowing students to pick the method that suits them best.

Mentors may have one or multiple mentees, and occasionally more than one person may mentor a group of mentees.Citation8,Citation51,Citation52,Citation58,Citation60,Citation63,Citation73 Interestingly, some initiatives use student peer mentoring to support physician mentoring.Citation25,Citation59 Once the relationship has been initiated, mentees and mentors usually meet face-to-face, but increasingly other forms of communication are used, including via email and telephone.Citation9,Citation51,Citation58 Frequency of meetings depends on the aims of the particular program .Citation7,Citation51,Citation58,Citation63,Citation73 Many meetings take place in the clinical or university environmentCitation62 but other schemes require meeting outside of work in a neutral environment.Citation12,Citation62 Mentoring activities tend to occur over a substantial period of time to help cultivate successful mentor relationships,Citation7,Citation31 with one study showing that mentees were more likely to share personal problems and socialize with their mentors 6 months after initiation of the program.Citation65

Finally, topics covered at meetings vary significantly, both within one scheme, and when compared with other mentoring programs. Examples include the following: simulation,Citation73 clinical supervision/shadowing,Citation7,Citation9 feedback and discussion on specific mentee selected topics,Citation61,Citation73 ethics,Citation63 career planning,Citation56 and personal development plans;Citation56,Citation62 to highlight but a few. These meetings can be informal or in the form of seminars and tutorials.Citation55 In this way, a range of mentees’ needs can be met by means of a more holistic approach to medical learning.

Evaluating medical mentoring programs

Most mentoring programs are evaluated to some extent but the quality of this evaluation is variable. Many assess shortterm impact that are conducted within a short period of time at the end of a program, for example, after a week.Citation29,Citation62,Citation67 Programs that evaluate on a more frequent basis use results to continuously make improvements to the design and delivery of the mentoring initiative.Citation25

Very few initiatives look at long-term effectiveness. One example is the Stanford Medical Youth Science Program, a widening participation program for high school pupils from under-represented minority groups. Its aim is to support these students in developing the skills required for college admission. The program followed 96% of candidates for up to 18 years, with 81% of pupils having earned a 4-year college degree, of which 52% had graduated from medical or graduate school. The authors concluded that 10 years was a sufficient follow-up duration.Citation47

A combination of qualitative and quantitative evaluation is usually undertaken, with the use of surveys being the most common method employed to appraise a program. These include the Likert scale, Yes/No surveys, and open-ended questions.Citation7,Citation61,Citation67 Other methods include focus groups,Citation12,Citation73 and semi-structured,Citation63 and telephone interviews.Citation66 Quantitative analysis usually consists of descriptive analysis. Less commonly, statistical tests, such as the unpaired t-test, chisquared, and Wilcoxon tests are used,Citation25,Citation60 allowing groups of students to be compared and differences measured.

The sample population for evaluation surveys tends to be mentees or both mentors and mentees.Citation7,Citation9,Citation25,Citation62,Citation67,Citation72 Few look only at the mentors’ perspective.Citation64 Questions are based on expert advice,Citation29 frameworks,Citation74 and literature.Citation7,Citation57,Citation60,Citation63,Citation67 Few are based on previously validated surveysCitation25,Citation29,Citation65 or are piloted before use,Citation8,Citation29,Citation51,Citation66,Citation74 which fails to prove the questionnaire is suitable to be used in this context. Control groups are rarely used to evaluate programs designed for only a subset of the student population,Citation66 thus it is difficult to compare groups and test the true effect of the mentoring provided.

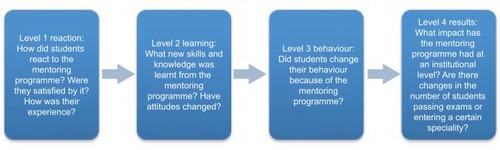

One tool to measure effectiveness is the Kirkpatrick model.Citation75 This evaluation framework has four sequential levels, where information at each level affects the next (). If a mentoring program is intended to bring about institutional change, such as an increase in numbers of students being accepted into a speciality, then Level 4 evaluation is needed. However, few mentoring programs do this and next to none look at cost effectiveness. This may be because it is more difficult to evaluate programs as levels increase, despite the value of information increasing at each level.Citation76 Mentoring programs that have evaluated at Level 4 tend to cover objectives related to research and have tangible outcomes, such as number of publications, presentations, awards, and higher degrees.Citation31,Citation50,Citation55,Citation71 Others look at exam success and number of students who later enter a speciality-training program.Citation50,Citation71,Citation73

Figure 2 The Kirkpatrick model.

Most programs evaluate at Level 1 and mainly explore mentee satisfaction.Citation29,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61–Citation63,Citation67,Citation70,Citation73 This is unsurprising as it is relatively the easiest form of evaluation to perform. Furthermore, institutions value high satisfaction scores as this can lead to an increase in the number of students applying and enrolling on to courses, thereby increasing revenue.

Some programs evaluate the impact of their initiative by measuring changes in mentees’ knowledge, skills, and attitude (Level 2).Citation8,Citation25,Citation29,Citation52,Citation66 Fewer schemes explore if a change in behavior has occurred as a result of participation in the program (Level 3), for example, if mentees subsequently changed their choice of residency.Citation12,Citation52

On the whole, mentoring programs do well in demonstrating short-term mentee and mentor satisfaction, but few evaluate beyond this to consider the impact at an institutional level. To do so would require clear, measurable outcomes, including cost effectiveness, alongside the use of validated and reliable tools of assessment. Although, this may require time and funding, it would enable an insight into the true long-term benefits of a mentoring initiative.

Benefits of mentoring

Mentoring programs have been shown to be of value to mentees, mentors, and institutions, including medical schools and benefits can be seen in . Mentoring has been identified as crucial to the retention and recruitment of trainees in medical and surgical specialties, as well as promoting research and academia. One example is a recent study of a research-mentoring program for junior doctors and medical students within a Melbourne cardiothoracic surgery department. The study covered a 10-year period, and reported success in engaging students early in training, with 81% of mentees publishing at least one research article, attainment of scholarships, doctoral degrees, and recruitment to cardiothoracic specialty training. The authors concluded that academic mentoring benefitted not only the individuals’ careers, but also ensured that the unit was able to maintain a high research output.Citation31

Table 1 Summary: potential benefits of mentoring

Similarly, a 2015 study at the Boston School of Medicine evaluated a medical student mentorship program for students keen to pursue a career in neurology. The program provided guidance as well as teaching and research opportunities, and peer teaching/mentoring in the run up to exams. Results included an increase in the number of students entering neurology, as well as an increase in research publications, poster presentations, and a book chapter since the implementation of the program 5 years prior.Citation77

A final example is of a recent trainee-led mentorship program in general surgical recruitment in Ireland. A total of 89% of mentees reported a positive impact on their decision to pursue a surgical career. Other benefits included a self-perceived improvement in technical ability, alongside guidance and information about a career, and training in surgery.Citation78 This study also highlights the benefits of near-peer mentoring, developing a trainee-led program in order to bridge a perceived “generation gap” between consultants and students. Studies in anesthesiology,Citation79 family medicine/primary care,Citation12,Citation80 and plastic surgeryCitation81 also report similar academic and recruitment benefits.

Near-peer mentoring is now increasingly prevalent at medical schools and has been shown to have a range of benefits, including improving student’s exam scores,Citation43 acquisition of procedural skills,Citation41,Citation82 and in improving the communication skills and personal and professional development of both mentors and mentees.Citation74,Citation83 Medical students also usually volunteer as mentors, with the incentive that the experience can be included as evidence of teaching in their personal and professional development portfolios. This can also reduce potential departmental reimbursement costs.Citation38,Citation41,Citation43 As previously discussed, widening participation programs also employ the use of near-peer mentoring, with medical students acting as role models and counseling school students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. This can, in turn, benefit the institutions’ social accountability agendas, by forging networks with schools from these communities and guiding students toward a career in the medical profession.Citation45,Citation84

Challenges to mentoring

The benefits of mentorship programs are well recognized, however, effective delivery of such programs can face a number of challenges. Challenges can arise from the fact that mentors are often clinician-educators who may not have received adequate training when taking on the role of a mentor. The need to provide mentors with clear expectations of their roles, and equip them with means to develop key listening and feedback skills, as well as knowledge of professional boundaries was highlighted by Ramani et al in “Twelve tips for effective mentors” and remains relevant.Citation22 A study of the challenges reported by mentors at the Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo highlighted difficulties surrounding expectations about the mentoring role and activities.Citation85 Similar concerns were also raised by mentors at the University of Washington School of Medicine.Citation86

Moreover, mentee engagement with mentoring can also pose a problem with a number of studies reporting low student participation.Citation83,Citation85 Similarly, a 2018 study of a mentorship program at King Abdulaziz University Faculty of Medicine, Saudi Arabia, reported that group meetings and one-on-one meetings were attended by only 60% and 49% of all students, respectively.Citation87 The authors concluded that sustained mentor and administration staff motivation is prerequisite for a successful mentoring program.

A study of final-year medical student–junior doctor mentorship program at Great Western Hospital, Swindon found that despite 96% of students recommending the scheme, not all students felt that they needed a mentor, and 20% of students chose not to have any contact with their mentor.Citation7 Nevertheless, students have also faced challenges in finding a mentor, particularly in academia – in one study, 44% of students were able to find a suitable research mentor with ease.Citation31 It is, therefore, imperative to identify students who want or need a mentor and assist in matching them with suitable mentors.

Mentors have also reported difficulties in undertaking mentoring sessions alongside their other core commitments, for example, clinical and academic responsibilities, due to time constraints.Citation7,Citation85 In these cases, protected time for mentors may be necessary to cultivate positive mentee–mentor relationships.Citation22

Implication and future of mentoring

Mentoring programs are increasingly recognized in medical schools as crucial components of the curriculum, and can aid in developing students’ professionalism, personal growth, knowledge, and skills. They have also been shown to be of benefit in the retention and recruitment of trainees to under-subscribed specialities, including academic medicine. Medical student mentors are able to develop their teaching and communication skills, as well as contribute to widening access programs that can help to increase diversity in the medical profession.

Design and delivery of these programs can vary significantly, making direct comparisons difficult. Nonetheless, most mentors receive training on appointment, however, may not be reimbursed financially or with protected time for mentoring activities. Furthermore, some students do not feel they need a mentor and this can affect the success of a mentoring relationship and engagement. It is, therefore, important for mentees and mentors to be matched in a way that encourages their relationship to succeed, whether this is by mentees choosing their mentor or using a validated matching tool.

The quality of evaluation that occurs varies. Few programs follow the students over an extended period of time to assess the long-term impact of a mentoring initiative. The majority of programs use surveys to assess students’ experiences and satisfaction, with only a few evaluating tangible outcomes, such as examination results. It is, therefore, hard to establish best practice. Despite this, mentoring has the potential to bring multiple benefits to mentees, mentors, and institutions.

Take-home messages

Finally, in order to develop a sustainable and effective mentoring program, we highlight the following key messages:

Before a mentoring program is established, a needs analysis or/and pilot should be undertaken to ensure that the design and intended goals are appropriate and achievable.

Programs should have clear measurable objectives and outcomes, both short and long term.

Mentees and mentors should be matched in a way that encourages their relationship to succeed. This may be through a validated matching process or mentees choosing their own mentor.

Mentors should receive training in the requirements of the role and in delivering effective feedback. Incentives should be offered, for example, recognition of mentoring for promotion. Likewise, mentees should be made aware of what is expected of them.

Protected time should be allocated for mentoring activities to encourage engagement and motivation.

Evaluation should include the mentee, mentor, and institution, and follow the mentee through an extended period of time to assess long-term impact of the initiative.

Evaluation should utilize validated methods of assessment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Oxford DictionaryMentor definitionOxfordOxford University Press2018 Available from: https://www.oxforddictionaries.com/Accessed August 10, 2018

- KeshavanMSTandonROn mentoring and being mentoredAsian J Psychiatr201516848626384741

- FreiEStammMBuddeberg-FischerBMentoring programs for medical students--a review of the PubMed literature 2000–2008BMC Med Educ20101013220433727

- SiddiquiSOf mentors, apprenticeship, and role models: a lesson to relearn?Med Educ Online20141912542825148889

- JacobiMMentoring and undergraduate academic success: a literature reviewRev Educ Res1991614505532

- RashidPNarraMWooHMentoring in surgical trainingANZ J Surg201585422522925649003

- HawkinsAJonesKStantonAA mentorship programme for final-year studentsClin Teach201411534534925041666

- DalgatyFGuthrieGWalkerHStirlingKThe value of mentorship in medical educationClin Teach201714212412826848105

- TranKTranGTFullerRWest Yorkshire mentor scheme: teaching and developmentClin Teach2014111485224405920

- KolliasCBanzaLMkandawireNFactors involved in selection of a career in surgery and orthopedics for medical students in MalawiMalawi Med J2010221202321618844

- FarrellTWShieldRRWetleTNandaACampbellSPreparing to care for an aging population: medical student reflections on their clinical mentors within a new geriatrics curriculumGerontol Geriatr Educ201334439340824138182

- IndykDDeenDFornariASantosMTLuWHRuckerLThe influence of longitudinal mentoring on medical student selection of primary care residenciesBMC Med Educ20111112721635770

- ZinkTHalaasGWFinstadDBrooksKDThe rural physician associate program: the value of immersion learning for third-year medical studentsJ Rural Heal2008244353359

- HoffmannJCFlugJAA call to action for medical student mentoring by young radiologistsCurr Probl Diagn Radiol201645215315426384704

- KashkoushAFerozeRMyalSFostering student interest in neurologic surgery: the University of Pittsburgh experienceWorld Neurosurg201710810110628866067

- BergerAPGiacaloneJCBarlowPKapadiaMRKeithJNChoosing surgery as a career: early results of a longitudinal study of medical studentsSurgery201716161683168928161006

- Assosication of American Medical CollegesThe hidden curriculum in academic medicine2015 Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5V8u9zqFaIAccessed August 10, 2018

- FeudtnerCChristakisDAChristakisNADo clinical clerks suffer ethical erosion? Students’ perceptions of their ethical environment and personal developmentAcad Med19946986706798054117

- SatterwhiteWM3rdSatterwhiteRCEnarsonCEMedical students’ perceptions of unethical conduct at one medical schoolAcad Med19987355295319609866

- KirchDGGusicMEAstCUndergraduate medical education and the foundation of physician professionalismJAMA2015313181797179825965213

- ElliottDDMayWSchaffPBShaping professionalism in preclinical medical students: professionalism and the practice of medicineMed Teach2009317e295e30219811137

- RamaniSGruppenLKachurEKTwelve tips for developing effective mentorsMed Teach200628540440816973451

- EleyDSJensenCThomasRBenhamHWhat will it take? Pathways, time and funding: Australian medical students’ perspective on clinician-scientist trainingBMC Med Educ201717124229216896

- MeijsLZusterzeelRWellensHJGorgelsAPThe Maastricht-Duke bridge: an era of mentoring in clinical research – a model for mentoring in clinical research – a tribute to Dr. Galen WagnerJ Electrocardiol2017501162027866647

- DimitriadisKvon der BorchPStörmannSCharacteristics of mentoring relationships formed by medical students and facultyMed Educ Online201217117242

- ChangYRamnananCJA review of literature on medical students and scholarly research: experiences, attitudes, and outcomesAcad Med20159081162117325853690

- FunstonGPiperRJConnellCFodenPYoungAMO’NeillPMedical student perceptions of research and research-orientated careers: an international questionnaire studyMed Teach201638101041104827008336

- WhiteMTSatterfieldCABlackardJTEssential competencies in global health research for medical trainees: a narrative reviewMed Teach201739994595328504028

- DeviVRamnarayanKAbrahamRRPallathVKamathAKodidelaSShort-term outcomes of a program developed to inculcate research essentials in undergraduate medical studentsJ Postgrad Med201561316316826119435

- O’SullivanPSNiehausBLockspeiserTMIrbyDMBecoming an academic doctor: perceptions of scholarly careersMed Educ200943433534119335575

- FrickeTALeeMGYBrinkJD’UdekemYBrizardCPKonstantinovIEEarly mentoring of medical students and junior doctors on a path to academic cardiothoracic surgeryAnn Thorac Surg2018105131732029191360

- FaucettEAMcCraryHCMilinicTHassanzadehTRowardSGNeumayerLAThe role of same-sex mentorship and organizational support in encouraging women to pursue surgeryAm J Surg2017214464064428716310

- O’ConnorMIMedical school experiences shape women students’ interest in orthopaedic surgeryClin Orthop Relat Res201647491967197227084717

- RohdeRSWolfJMAdamsJEWhere are the women in orthopaedic surgery?Clin Orthop Relat Res201647491950195627090259

- Southampton UniversitySouthampton university BM62018 Available from: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/meded/curriculum_design_and_delivery/bm6.pageAccessed July 17, 2018

- Kings CollegeKings College extended medical degree programme2018 Available from: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/courses/extended-medical-degree-programme-mbbs.aspxAccessed July 12, 2018

- DerckJZahnKFinksJFMandSSandhuGDoctors of tomorrow: an innovative curriculum connecting underrepresented minority high school students to medical schoolEduc Health (Abingdon)201629325926528406112

- SmithSAlexanderADubbSMurphyKLaycockJOpening doors and minds: a path for widening accessClin Teach201310212412823480116

- FreemanBKLandryATrevinoRGrandeDSheaJAUnderstanding the leaky pipeline: perceived barriers to pursuing a career in medicine or dentistry among underrepresented-in-medicine undergraduate studentsAcad Med201691798799326650673

- NicholsonSClelandJA“It’s making contacts”: notions of social capital and implications for widening access to medical educationAdv Health Sci Educ2017222477490

- Garcia-CasasolaGSánchezFJLuordoDBasic abdominal point-of-care ultrasound training in the undergraduate: students as mentorsJ Ultrasound Med201635112483248927738292

- BarkerTANgwenyaNMorleyDJonesEThomasCPColemanJJHidden benefits of a peer-mentored ‘Hospital Orientation Day’: first-year medical students’ perspectivesMed Teach2012344e229e23522455714

- TaylorJSFaghriSAggarwalNZellerKDollaseRReisSPDeveloping a peer-mentor program for medical studentsTeach Learn Med20132519710223330902

- ChoudhuryNKhanwalkarAKraningerJVohraAJonesKReddySPeer mentorship in student-run free clinics: the impact on preclinical educationFam Med201446320420824652639

- KarpaKVakhariaKCarusoCAVecheryCSippleLWangAMedical student service learning program teaches secondary students about career opportunities in health and medical fieldsAdv Physiol Educ201539431531926628654

- AzmyJNimmonsDReflections on a widening participation teaching roleClin Teach201714213914027860264

- WinklebyMAThe Stanford Medical Youth Science Program: 18 years of a biomedical program for low-income high school studentsAcad Med200782213914517264691

- NimmonsDDeveloping mentoring skills as a studentClin Teach2016131727326095470

- Al-KhudairiRJameie-OskooeiSLoboRDealing with emotions in medical school: are senior students preferable to mentors?Med Educ201751445228118691

- BoningerMTroenPGreenEImplementation of a longitudinal mentored scholarly project: an approach at two medical schoolsAcad Med201085342943720182115

- MacaulayWMellmanLAQuestDONicholsGLHaddadJPuchnerPJThe Advisory Dean Program: a personalized approach to academic and career advising for medical studentsAcad Med200782771872217595575

- McGeehanJEnglishRShenbergerKTracyGSmegoRA community continuity programme: volunteer faculty mentors and continuity learningClin Teach2013101152023294738

- DenunzioNParekhAHirschAEMentoring medical students in radiation oncologyJ Am Coll Radiol20107972272820816635

- McLaughlinKVealePMcIlwrickJde GrootJWrightBA practical approach to mentoring students with repeated performance deficienciesBMC Med Educ20131315623597111

- YagerJWaitzkinHParkerTDuranBEducating, training, and mentoring minority faculty and other trainees in mental health services researchAcad Psychiatry200731214615117344457

- PinillaSPanderTvon der BorchPFischerMRDimitriadisK5 years of experience with a large-scale mentoring program for medical studentsGMS Z Med Ausbild2015321 Doc5

- FornariAMurrayTSMenzinAWMentoring program design and implementation in new medical schoolsMed Educ Online20141912457024962112

- MeinelFGDimitriadisKvon der BorchPStörmannSNiedermaierSFischerMRMore mentoring needed? A cross-sectional study of mentoring programs for medical students in GermanyBMC Med Educ20111116821943281

- SchäferMPanderTPinillaSFischerMRvon der BorchPDimitriadisKA prospective, randomised trial of different matching procedures for structured mentoring programmes in medical educationMed Teach201638992192926822503

- SinghSSinghNDhaliwalUNear-peer mentoring to complement faculty mentoring of first-year medical students in IndiaJ Educ Eval Health Prof2014111224980428

- KmanNEBernardAWKhandelwalSNagelRWMartinDRA tiered mentorship program improves number of students with an identified mentorTeach Learn Med201325431932524112201

- SobbingJDuongJDongFGraingerDResidents as medical student mentors during an obstetrics and gynecology clerkshipJ Grad Med Educ20157341241626457148

- KalénSPonzerSSeebergerAKiesslingASilénCLongitudinal mentorship to support the development of medical students’ future professional role: a qualitative studyBMC Med Educ20151519726037407

- SchecklerWETuffliGSchalchDMacKinneyAEhrlichEThe class mentor program at the University of Wisconsin Medical School: a unique and valuable asset for students and facultyWMJ200410374650

- LinCDLinBYLinCCLeeCCRedesigning a clinical mentoring program for improved outcomes in the clinical training of clerksMed Educ Online20152012832726384479

- CoatesWCCrooksKSlavinSJGuitonGWilkersonLMedical school curricular reform: fourth-year colleges improve access to career mentoring and overall satisfactionAcad Med200883875476018667890

- BhatiaANavjeevanSDhaliwalUMentoring for first year medical students: humanising medical educationIndian J Med Ehtics2013102100103

- KostrubiakDEKwonMLeeJMentorship in radiologyCurr Probl Diagn Radiol201746538539028460792

- WeinsteinLA special programme to revitalise the senior physician while improving the clinical education and mentoring of medical students and residentsBJOG20171247102728544715

- MartinaCAMutrieAWardDLewisVA sustainable course in research mentoringClin Transl Sci20147541341924889332

- AreephanthuCJBoleRStrattonTKellyTHStarnesCPSawayaBPImpact of professional student mentored research fellowship on medical education and academic medicine career pathClin Transl Sci20158547948325996460

- WeinerJSmallACLiptonLREstablishing an online mentor database for medical studentsMed Educ201448554254324712963

- KaletAKrackovSReyMMentoring for a new eraAcad Med2002771111711172

- KalénSStenfors-HayesTHylinULarmMFHindbeckHPonzerSMentoring medical students during clinical courses: a way to enhance professional developmentMed Teach2010328e315e32120662566

- SmidtABalandinSSigafoosJReedVAThe Kirkpatrick model: a useful tool for evaluating training outcomesJ Intellect Dev Disabil200934326627419681007

- BewleyWLO’NeilHFEvaluation of medical simulationsMil Med201317810 Suppl647524084307

- ZuzuárreguiJRHohlerADComprehensive opportunities for research and teaching experience (CORTEX): a mentorship programNeurology201584232372237625957332

- AhmedONugentMCahillRMulsowJAttitudes to trainee-led surgical mentoringIr J Med Sci2018187382182629103174

- WenzelVGravensteinNAnesthesiology mentoringCurr Opin Anaesthesiol201629669870227764048

- MyhreDLSherlockKWilliamsonTPedersenJSEffect of the discipline of formal faculty advisors on medical student experience and career interestCan Fam Physician20146012e607e61225642488

- BarkerJCRendonJJanisJEMedical student mentorship in plastic surgery: the mentee’s perspectivePlast Reconstr Surg201613761934194227219246

- JeppesenKMBahnerDPTeaching bedside sonography using peer mentoringJ Ultrasound Med201231345545922368136

- Stenfors-HayesTKalénSHultHDahlgrenLOHindbeckHPonzerSBeing a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional developmentMed Teach201032214815320163231

- HendersonRIWilliamsKCrowshoeLLMini-med school for aboriginal youth: experiential science outreach to tackle systemic barriersMed Educ Online20152012956126701840

- GonçalvesMCBellodiPLMentors also need support: a study on their difficulties and resources in medical schoolsSao Paulo Med J2012130425225822965367

- DobieSSmithSRobinsLHow assigned faculty mentors view their mentoring relationships: an interview study of mentors in medical educationMentor Tutoring Partnersh Learn2010184337359

- FallatahHISoo ParkYFarsiJTekianAMentoring clinical-year medical students: factors contributing to effective mentoringJ Med Educ Curric Dev20185238212051875771729497707