Abstract

Purpose

Critical thinking underlies several Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)-defined core entrustable professional activities (EPAs). Critical-thinking ability affects health care quality and safety. Tested tools to teach, assess, improve, and nurture good critical-thinking skills are needed. This prospective randomized controlled pilot study evaluated the addition of deliberate reflection (DR), guidance with Web Initiative in Surgical Education (WISE-MD™) modules, to promote surgical clerks’ critical-thinking ability. The goal was to promote the application of reflective awareness principles to enhance learning outcomes and critical thinking about the module content.

Participants and methods

Surgical clerkship (SC) students were recruited from two different blocks and randomly assigned to a control or intervention group. The intervention group was asked to record responses using a DR guide as they viewed two selected WISE-MD™ modules while the control group was asked to view two modules recording free thought. We hypothesized that the intervention group would show a significantly greater pre- to postintervention increase in critical-thinking ability than students in the control group.

Results

Neither group showed a difference in pre- and posttest free-thought critical-thinking outcomes; however, the intervention group verbalized more thoughtful clinical reasoning during the intervention.

Conclusion

Despite an unsupported hypothesis, this study provides a forum for discussion in medical education. It took a sponsored tool in surgical education (WISE-MD™) and posed the toughest evaluation criteria of an educational intervention; does it affect the way we think? and not just what we learn, but how we learn it? The answer is significant and will require more resources before we arrive at a definitive answer.

Introduction

Critical thinking underlies at least three of the Association of American Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) 13-core entrustable professional activities (EPA) for entering residency.Citation1 Critical thinking is required for physicians to competently and independently provide patient care.Citation2 While critical-thinking ability is clearly related to quality and safety in health care,Citation3 defining and measuring it continue to be a challenge for health professions’ educators, including medical faculty.Citation4–Citation7

Defining critical thinking has been elusive for most of the recent century.Citation8 There is no consensus for an approved definition in the medical literature,Citation9 nor is there agreement on terminology to define the process and little evidence for best practices for teaching, measuring, and evaluating critical thinking.Citation4–Citation6 Others question whether critical thinking can even be taught.Citation4 What it means to think critically may vary by discipline, practice settings, and contexts.Citation10 Critical thinking may be viewed as a variety of ways to think with various styles of reasoning,Citation11 and in the health sciences’ literature, critical thinking is often used interchangeably with clinical thinking, clinical reasoning, and diagnostic reasoning.Citation10

Because critical thinking is largely conceptual, measurement must be inferred from observable behaviors.Citation6 Educational strategies to reveal actual thought processes may include a standardized list of questions – necessitating verbal or written evidence for analysis as a requirement to enhance metacognition and make visible a student’s thought processing.Citation4 Huang et alCitation4 reported the following strategies for teaching critical thinking: 1) slowing down the pace of the learning process to enable students to digest and apply knowledge, 2) actively engaging the learner in tasks that require problems to be solved, 3) compelling students to justify how they arrived at decisions, 4) making thinking explicit, and 5) requiring self-reflection on the part of the learner.

Given the literature and the above noted gaps, the authors wanted to test the integration of deliberate reflection (DR) with Web Initiative in Surgical Education (WISE-MD™) modules as a means to increase critical-thinking ability. Due to the timing of courses, semesters, and per the protocol submitted and approved as exempt by the institutional review board, the methodology was first tested with nurse practitioner students in an advanced health assessment courseCitation39 followed by implementation with medical students during their surgical clerkship (SC). This study evaluated critical-thinking outcomes of SC students by adding metacognitive DR guidance to the learning strategy with WISE-MD™ simulation modules. The authors hypothesized that SC students in the intervention group who were exposed to the DR guide would show a significantly greater pre- to postintervention increase in critical-thinking ability than students in the control group who had no DR guidance.Citation39 The next section provides additional details regarding the development of the methodology.

Rationale for the design strategies developed for this study

WISE-MD™

WISE-MD™ is a series of 35 case-based online teaching modules developed to fill in the gaps in surgical education created by shorter hospital stays along with more of the pre-and postoperative care occurring in outpatient services.Citation12,Citation13 The American College of Surgeons and the Association of Surgical Education endorsed the WISE-MD™ modules, which were designed to develop clinical reasoning in medical students while seeking consistent, high-quality learning environments to ensure clinical competence.Citation12,Citation13,Citation39 Among the module topics are those particularly germane to the SC such as appendicitis, breast cancer, gall bladder disease, thyroid disease, and hernias.Citation12,Citation13 The modules were created for independent study illustrated with video and animation using best practices for multimedia design.Citation12,Citation13,Citation39

Lasting ~1 hour, each module is introduced with a “fundamentals” section and depicts the patient’s experiences and interactions with the physician from initial presentation, history taking, physical examination, laboratory tests and radiological imaging to preoperative preparation, surgery, and recovery.Citation12,Citation13,Citation39 Professionalism and communication are emphasized throughout each module, which also includes a summary and key findings from the case.Citation12,Citation13 The surgical procedure is presented with a graphic depiction alongside the actual surgery process overview, which is very helpful for medical student visualization of the virtual along with the actual surgery.Citation39 For the remainder of the document, the authors refer to the WISE-MD™ modules as the WISE modules.Citation39

Although the WISE modules have been used in medical education since 1998 and are used by >200 medical schools nationally and internationally,Citation12,Citation13 little has been published regarding their use with medical students. One study found that medical students who viewed the WISE modules trended toward better knowledge and clinical reasoning than students who did not view the modules.Citation14,Citation39

Reflective practice

To be able to think critically, students must learn to routinely and critically examine their own thinking.Citation6,Citation15 Requiring medical students to examine their own thinking through thoughtful reflection is an important component of medical educationCitation16–Citation18 as reflection requires the ability to think critically.Citation19 Reflective practice also promotes professional identity transformation from medical student to physicianCitation16 and seeks to improve diagnostic accuracy.Citation20,Citation21

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies and milestonesCitation22 and the AAMC’s Physician Competency Reference Set (PCRS)Citation23 require physician trainees to reflect upon and analyze practice experiences.Citation17 Reflective practice can be fostered/enhanced when medical students perceive the case/situation as real, there is some conflict, critical questions are raised, and there is a structured process for reflecting.Citation24 Guided reflection is considered a key element of professional identity formation from medical student to physicianCitation16 with an interactional aspect proposed to develop that identity.Citation25

Furthermore, clinical reasoning may be enhanced by the process of “think aloud”, which occurs when a student verbalizes his or her thoughts while doing an assignment.Citation26 SiddiquiCitation27 found think aloud to be valuable in identifying medical students’ critical-thinking strengths and weaknesses during their ICU rotation. Thus, given the potential value of both reflection and think aloud to make critical thinking overt and for the purposes of this study, author MQ created the term DR to reinforce the notion that the reflective thinking process is an overt skill that compliments the skill set of “deliberate practice” defined by Ericsson.Citation28 DR as a metacognitive learning innovation is tested in this study.

DR

The DR process is introduced for a number of reasons. It implies that the reflective process must be made overt to enhance learningCitation39 as suggested by Croskerry who defines “cognitive forcing strategies” as a means of de-biasing and preventing diagnostic error.Citation26,Citation39 Although similar to the metacognitive strategy known as self-explanation, DR differs in that it is not restricted to inferences, clarifications, justifications, or monitoring of behavior as is inherent in the definitions of self-explanation.Citation29–Citation31,Citation39 Rather, DR includes the integration of previous experiences with current experiences and the application of strategic knowledge about self and learning including awareness of affective components such as confidence.Citation40 DR incorporates mental representation (selective encoding, combination, and comparison) (A Kalet, New York University, email communication, May 2011.)Citation30,Citation39 and considers the temporal aspects of reflection – before action, during action, and after action.Citation32,Citation39 Finally, DR includes a think-aloud or “verbal report” strategy that has been used in debriefing and other thought process research strategies.Citation6,Citation39 Believing that the value of learning through simulation lies in debriefing and reflection on the simulation experienceCitation33 and that structured reflection improves learning outcomes,Citation28,Citation31,Citation34–Citation37,Citation39 the authors reasoned that without specific, systematic instructions for learner reflection or self-debriefing, some of the educational value of the video-based simulation in the WISE modules might be lost.Citation39 The authors further speculated that the personalized, real-time, self-debriefing/reflective component of DR for the SC students might improve the WISE module learning experience and outcomes related to working memory and critical thinking.Citation39 Therefore, for this study, the authors developed specific DR instructions to guide the SC learner to apply the principles of reflective awareness to surgical content in the WISE-MD™ modules with the goal of promoting learningCitation38 and enhancing critical-thinking and learning outcomes.Citation39

Participants and methods

Participants

We recruited the participants from two different blocks of SC students at a New England medical school during the fall semester. The study was presented to students during the first week of their rotation. Thirty-one (72%) of the 43 students volunteered to participate and were randomly assigned to either the control group (n=16) or the intervention group (n=15). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Participants were given access to all the WISE modules and provided with a digital recorder to record their thoughts as they completed several preselected modules: abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), cholecystitis, appendicitis, and thyroid nodule.Citation39 Participants received no compensation, viewed the modules, and completed assigned activities on their own time outside of class. Although participation would not influence their grade, SC students were told that the WISE modules might be seen as an advantage in terms of their overall learning.Citation39

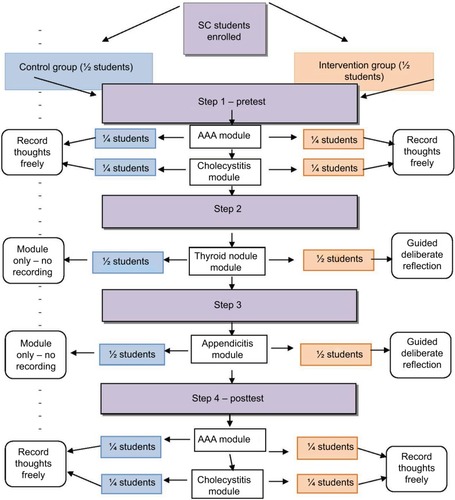

Procedure

As outlined in the WISE study flowchart in , there were four steps to the procedure for both the control and intervention groups ranging from pretest to posttest.Citation39

Figure 1 WISE-MD™ study flowchart.

Abbreviations: AAA, abdominal aortic aneurysm; SC, surgical clerkship; WISE-MD™, Web Initiative in Surgical Education.

Step 1/pretest

The intervention and control groups were divided into two subgroups as close to equal size as possible. One subgroup viewed the AAA module, and the other subgroup viewed the cholecystitis module.Citation39 Each student was provided with a digital recorder and asked to freely record their thoughts while viewing each module.Citation39 For this exercise, all students (both intervention and control) were provided with a “free-thought” guide requesting them to record out loud whatever happens to come across their mind at least three times while viewing the modules.

Step 2

The control group reviewed the thyroid module without using a digital recorder.Citation39 While viewing the same module, the intervention group used a digital recorder to answer questions from the DR think-aloud group instructions, which can be found in .Citation39 These instructions asked the intervention group to complete the specific DR exercises at specific time points.Citation39

Table 1 Deliberate reflection think-aloud instructions for thyroid nodule module

Step 3

The two groups followed the same procedures as described in step 2 for a second module, appendicitis.Citation39

Step 4/posttest

The two modules (AAA and cholecystitis) used in the pretest were again used in the posttest but switched.Citation39 Using the same free-thought guide as described in step 1, students in both the control and intervention groups were asked to record their thoughts freely while viewing the module.Citation39 Students submitted their digital recorders to the study coordinator (KS) for analysis once they completed the study.Citation39 All 31 study participants were sent a brief follow-up anonymous survey about their experience as a study participant, with the WISE modules.Citation39

Data analysis

Data from students’ digital recordings were transcribed into word documents and imported into NVIVO™ Version 10.Citation39 All authors iteratively coded the transcripts. They reviewed the critical-thinking literature for potential categories to reach con sensus on the final critical-thinking coding. Further description of the development of the categories can be found in the work of Terrien et al.Citation39 Final analysis determined five categories with 10 subcategories, which can be found in .Citation39

Table 2 Critical-thinking categories, subcategories, and explanations

Ethics

The study was exempted from review (14811) by the UMass Medical School Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research.

Results

Participants

Of the 31 SC study participants, 15 (48%) participants dropped out of the study. Of the 16 (52%) remaining par ticipants, 7 participants failed to complete all parts of the study. Nine (29%) students completed the entire study – four females and five males. Participants’ mean age was 25.77 years (range =23–29 years). All nine completers had a baccalaureate degree, and one had achieved a master’s degree. Eight were Caucasian and one was of Middle Eastern descent. Of those completing, four were from the intervention group and five were from the control group.

Comparison of critical-thinking outcomes by group

The control and intervention groups showed no difference in pre- and posttest free-thought critical-thinking outcomes. SC students in the intervention group demonstrated a higher level of critical thought when prompted by questions in the DR guide.Citation39 provides examples of SC students’ DR narratives from either the thyroid module or the appendicitis module that are representative of the critical-thinking category/subcategory.

Table 3 Critical-thinking outcomes by category and subcategory, with examples

During the free-thought steps (step 1 [pretest] and step 4 [posttest]) of methods, students in both the control and intervention groups predominantly verbalized in the categories of description, learning style, and occasionally their past experiences with the module topic. They described what they were seeing and hearing in the modules as an ongoing commentary about each section of the module. They also described what they liked/did not like (in terms of their learning styles) about the module, the narrator, and the interaction between the physician and the patient. Some evaluated or summarized the overall value of the module for them at the end of their free-thought recording. The free-thought narratives did not demonstrate clinical reasoning.

SC students’ feedback on WISE modules

Because of the large dropout rate (of the 31 SC learner participants, 15 [48%] participants dropped out of the study, and of the 16 [52%] remaining participants, 7 participants failed to complete all parts of the study), the authors sought to determine 1) the reasons for the high dropout/failure to complete rate and 2) the value of the modules to all students. All participants (31) were surveyed poststudy for qualitative feedback and quantitative feedback regarding the study and the modules; 15 (48%) of the 31 participants returned the survey, but not all 15 respondents responded to every question.

Discussion

The authors were disappointed that after having been exposed twice to the DR guidance, the performance of the intervention group on the last two modules did not continue to demonstrate the same high level of critical thinking as during the DR-guided modules (steps 2 and 3). Despite the lack of support for our hypothesis, we believe that DR has value and generates the following additional questions for consideration in future studies: 1) were we measuring the right concepts? 2) are two guided DRs insufficient for students to internalize, without the DR guidance, the same high level clinical reasoning process? and 3) would a formal debriefing process (online or face to face) have enhanced the students’ experience?Citation39 Ibiapina et al,Citation21 in their 2014 study of free reflection, modeled reflection, and cued reflection, found that with a higher amount of guidance, the structured reflection groups performed significantly better than the free-reflection group. These findings are consistent with our findings in that students with the guided/DR demonstrated a higher level of critical thinking versus unprompted free reflection.Citation39

We implemented the poststudy survey as an opportunity to “debrief ” the students in terms of what they did and did not find to be useful about the modules and the study. The feedback from the students in our study was similar to that found in other studies related to multimedia education enhancement strategies. Examples were as follows: 1) because of the fast pace of medical education, students become highly strategic in their selection of learning resources and unnecessary information is not appreciated;Citation40 it appears from the postsurvey that the SC students perceived the WISE modules to be in addition to other course expectations and students trusted their usual mode of studying and preparing for the examinations using their textbooks; and 2) the pressure of end of clerkship examination and the National Board of Medical Examiners’ (NBME) subject examination along with their perception of limited time to try out a new way of learning created barriers to their enthusiasm for the modules.Citation41 This is consistent with Yavner et al,Citation40 who emphasized the importance of faculty making clear the purpose and value of any additional online initiatives. As in the Ellaway et alCitation41 study, the students found the modules to be very useful when they had adequate time to prepare for a known specific case with which they were going to be involved. Consistent with Ellaway et al,Citation41 SC students complained that even during “downtime” in clinical settings, they were not permitted to use electronic devices. The students expressed that this would have been an ideal time to review modules, particularly just prior to an upcoming case. Both the SC students and those of Ellaway appreciated the split screen videos of the virtual and actual surgery.Citation41

The authors believe after completing and analyzing the data that requiring the DR guidance for every module may have increased the likelihood of students developing and internalizing a thought pattern or process that enhanced their clinical reasoning.Citation39 In addition, critical thinking as a response style may only become a habit if practiced over time. Perhaps students would need more than two opportunities for the application of guided (deliberate) reflectionCitation24,Citation39 suggesting that learning a new automatic pattern of thinking is enhanced by practice and observing expert modeling of critical thinking over time.Citation39,Citation42

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. The pilot study was conducted at a single academic institution in New England, with a limited number of students, only 29% of whom completed the study. The time frame for the study was short, and the intervention group was instructed to use DR guidance with only two of the WISE modules. The outcomes measured were author-defined rather than consensually defined constructs: 1) critical thinking, which lacks an expert consensus definition; 2) the process of DR, developed by the study team; and 3) researcher-developed, not previously tested categories of critical thinking.Citation39 Additionally, this study was a one-time brief commitment of the entire clerkship curriculum for third-year medical students, thus, only a short-term “injection” within the four-year medical education process.Citation24

Implications for medical education

Despite the small number, high dropout rate, and lack of support for the hypothesis, we believe that this study has implications for health professions’ curriculaCitation39 and provides a forum for discussion in medical education. Introducing this approach to – and level of thinking to – students ab initio might be the best way to ensure that DR remains with them throughout their academic and professional lives. Implementing the DR approach to problem solving beginning in year 1 and then threading it throughout all 4 years of medical school might enhance the impact of DR on critical thinking.

The feedback from the post-study survey was valuable in terms of a debriefing strategy. Some of the students’ feedback was similar to that found in other studiesCitation41 that participants in both the intervention and control groups valued using the WISE modules. The authors believe that the WISE modules offer SC students a unique resource for them to follow a complete interaction between an experienced surgeon and patient for the core disease processes in surgery. Students can pace themselves and use the resource 24/7. They can start and stop the program at will depending on available time to offer a chance for reflection on the covered material.Citation39 The modules are a key resource for students preparing for oral examinations as well as objective structured clinical examinations. The program is comprehensive such that all aspects of any given clinical problem are covered from epidemiology to symptoms, diagnostic workup, and treatment algorithms so that the material serves as good review for the written NBME examination as well. Many of the modules have videos and other graphic materials that can help the students review anatomy and acquire knowledge of the procedure prior to participation in the surgical suite.

Conclusion

Despite no difference in unprompted outcomes between groups, the intervention group verbalized more thoughtful clinical decision-making when following the DR protocol.Citation39 The authors now believe that limiting the application of DR with only two modules was not sufficient for students to internalize a new way of thinking about clinical cases. We suggest that DR could be integrated throughout medical education as a means to reinforce learning with a defined model to promote critical thinking for clinical reasoning. It would be of particular interest to see how many guided DR modules it might take for students to begin to verbalize and record their critical-thinking processes without prompting from the requirements of the DR protocol.Citation39

Faculty must identify and test strategies that will help learners develop and enhance good critical-thinking skills.Citation39 The value of this study is that it takes a legitimate and sponsored tool in surgical education (WISE-MD™) and poses the toughest criteria of evaluation of an educational intervention, ie, does it affect the way we think? and not just what we learn (but how we learn it)?Citation39 Finding out the answer is significant and will require more resources before we arrive at a definitive answer.Citation39

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a $21,963.00 grant from the Institute for Innovative Technology in Medical Education (iInTIME).

The authors wish to acknowledge the SC students who participated in the study and provided important feedback and the valuable assistance and support from Victoria Rossetti, Education and Clinical Services Librarian, Lamar Soutter Library, University of Massachusetts Medical School. This article reports on the second pilot study (surgical clerkship students) that used exactly the same study design as the initial pilot with nurse practitioner students, which was published in the Journal of Nursing Education and Practice.

Disclosure

JMT served as a voluntary member of the Editorial Board of WISE-MD(™) Leadership 2013–2017. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EnglanderRFlynnTCallSToward defining the foundation of the MD degree: core entrustable professional activities for entering residencyAcad Med201691101352135827097053

- ten CateOScheeleFViewpoint: competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice?Acad Med200782654254717525536

- ShojaniaKBurtonEMcDonaldKGoldmanLChanges in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic reviewJ Am Med Assoc20032812928492856

- HuangGCNewmanLRSchwartzsteinRMCritical thinking in health professions education: summary and consensus statements of the Millennium Conference 2011Teach Learn Med20142619510224405353

- GortonKLHayesJChallenges of assessing critical thinking and clinical judgment in nurse practitioner studentsJ Nurs Educ2014533S26S2924530011

- PappKKHuangGCLauzon ClaboLMMilestones of critical thinking: a developmental model for medicine and nursingAcad Med201489571572024667504

- CharlinBLubaraskySMilletteBClinical reasoning processes: unravelingcomplexity through graphic representationMed Educ201246545446322515753

- YancharSCSlifeBDWarneRCritical thinking as disciplinary practiceRev Gen Psychol2008123265

- KrupatESpragueJMWolpawDHaidetPHatemDO’BrienBThinking critically about critical thinking: ability, disposition or both?Med Educ201145662563521564200

- KahlkeRWhiteJCritical thinking in health sciences education: considering “Three Waves”Creative Educ201341221

- MasonMCritical Thinking and Learning HobokenNJWiley-Blackwell2008

- MedUWISE-MD Surgical Modules2017 Available from: https://aquifer.org/about-aquifer/courses/.

- MedUMore About WISE-MD2017 Available from: https://aquifer.org/courses/Accessed July 29, 2016

- KaletALCoadySHHopkinsMAHochbergMSRilesTSPreliminary evaluation of the Web Initiative for Surgical Education (WISE-MD)Am J Surg20071941899317560916

- Sheriff LeVanKKingMFaculty FocusBuilt-in Self-Assessment: A Case for AnnotationMadison, WIMagna Publications2015

- WaldHProfessional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilienceAcad Med201590670170625881651

- DevlinMBoydFCunninghamH“Where does the circle end?” Representation as a critical aspect of reflection in teaching social and behavioral sciences in medicineAcad Psychiatry2015201539669677

- WaldHBorkanJScott TaylorJAnthonyDReisSFostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writingAcad Med2012871415022104060

- GoldieJThe formation of professional identity in medical studnets: considerations for educatorsMed Teach2012349e641e64822905665

- MamedeSSchmidtHPenaforteJEffects of reflective practice on the accuracy of medical diagnosesMed Educ2008200842468475

- IbiapinaCMamedeSMouraAEloi-SantosSGogTEffects of free, cued and modelled reflection on medical students’diagnostic competenceMed Educ201448879680525039736

- ACGMEThe Milestones Handbook2016 http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Resources/Guidebook

- AAMC [webpage on the Internet] Physician Competencies Reference Set2013 Available from: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/about/348808/aboutpcrs.htmlAccessed July 28, 2016

- LewinLRobertNRaczekJCarraccioCHicksPAn online evidence based medicine exercise prompts reflection in third year medical studentsBMC Med Educ20141416425106435

- MonrouxeLIdentity, identification and medical education: why should we care?Med Educ2010441404920078755

- PinnockRYoungLSpenceFHenningMHazellWCan think aloud be used to teach and assess clinical reasoning in graduate medical education?J Grad Med Educ20157333433726457135

- SiddiquiSThink-aloud protocol for ICU rounds: an assessment of information assimilation and rational thinking among traineesMed Educ Online2014192578325326045

- EricssonKADevelopment of Professional Expertise: Toward Measurement of Expert Performance and Design of Optimal Learning EnvironmentsNew York, NYCambridge University Press2009

- ChiMTSelf-explaining expository texts: the dual processes of generating inferences and repairing mental modelsAdv Instruct Psychol20005161238

- RenklALearning from worked-out examples: a study on individual differencesCogn Sci1997211129

- ChenMYehYSelf-explanation strategies in undergraduate studentsJ Hum Resour Adult Learn200841179188

- SchonDAEducating the Reflective PractitionerSan Francisco, CAJossey-Bass1987

- DreifuerstKTThe essentials of debriefing in simulation learning: a concept analysisNurs Educ Perspect200930210911419476076

- McDonaldJDominguezLDeveloping patterns for learning in science through reflectionJ Coll Sci Teach20093913942

- ChiMTHBassokMLewisMWReimannPGlaserRSelf-explanations: how students study and use examples in learning to solve problemsCogn Sci1989132145182

- ChiMTHde LeeuwNChiuM-HLaVancherCEliciting self-explanations improves understandingCogn Sci1994183439477

- PateMLWardlowGWJohnsonDMEffects of thinking aloud pair problem solving on the troubleshooting performance of undergraduate agriculture students in a power technology courseJ Agric Educ2004454111

- EricssonKAProtocol analysis and expert thought: concurrent verbalizations of thinking during experts’ performance on representative tasksThe Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert PerformanceNew YorkCambridge University Press2006223242

- TerrienJMHaleJFCahanMQuirkMSullivanKLewisJThe impact of deliberate reflection with WISE-MD™ modules on critical thinking of nurse practitioner students: a prospective, randomized controlled pilot studyJ Nurs Educ Pract20166155

- YavnerSDPusicMVKaletALTwelve tips for improving the effectiveness of web-based multimedia instruction for clinical learnersMed Teach201537323924425109353

- EllawayRHPusicMYavnerSKaletALContext matters: emergent variability in an effectiveness trial of online teaching modulesMed Educ201448438639624606622

- ShinHMaHParkJJiESKimDHThe effect of simulation course-ware on critical thinking in undergraduate nursing students: multi-site pre-post studyNurse Educ Today201535453754225549985