Abstract

Introduction

Self-directed learning (SDL) and problem-based learning (PBL) are fundamental tools to achieve lifelong learning in an integrated medical curriculum. However, the efficacy of SDL in some clinical courses is debated.

Aim

The aim of the study was to measure the effectiveness of SDL for an ophthalmology course in comparison with PBL.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with fifth-year medical students enrolled in an ophthalmology course. SDL comprised four case-based scenarios guided by several questions. PBL comprised three sessions. An ear, nose, and throat (ENT) course was selected for comparison as a control. At the end of the course, 30 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) for both SDL and PBL were assessed and analyzed against their counterparts in the ENT course by an independent t-test.

Results

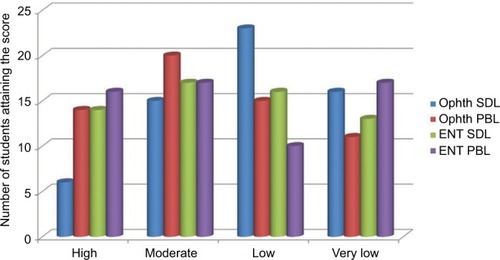

For the SDL component of the ophthalmology course, the number and percentages of students attaining high (n = 6/60, 10%) and moderate (n = 15/60, 28.3%) scores on an MCQs written exam were evaluated. For the PBL component, high scores were seen for 23.3% (n = 14/60), and moderate scores for 33.3% (n = 20/60) of the participants. For the SDL component of the ENT course, the number and percentages of students attaining high (n = 14/60, 23.3%) and moderate (n = 17/60, 28.3%) scores were recorded. For the PBL component, high (16/60, 26.6%) and moderate (17/60, 28%) scores were recorded. Significant p-values were obtained between the results for SDL and PBL in the ophthalmology course (p = 0.009), as well as between SDL results for both courses (p = 0.0308). Moreover, differences between the SDL results of ophthalmology and the PBL results of ENT (p = 0.0372) were significant.

Conclusion

SDL appears to be less valuable for promotion of self-readiness. Periodic discussions in small groups or by panel discussion are strongly recommended for students to enhance readiness with SDL.

Introduction

Self-directed learning (SDL) is an essential proficiency skill for medical practitioners and, as such, is a component of the medical curriculum at an early stage. Multiple modalities have been used for providing SDL instruction to undergraduate students, with numerous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of SDL as a means to increase student readiness and enthusiasm.Citation1–Citation3 The multiple SDL modalities found in various medical curricula are effective if the objectives are realistic and accomplishable, ensuring that learners can apply SDL modalities to situations wherein they are required to learn by themselves.Citation4–Citation6 One instructional SDL modality is the presentation of case-based scenarios that guide learners by posing multiple problem-related questions. Those questions direct the learner to respond by using suggested learning resources.Citation7–Citation9

SDL is an efficient and effective learning tool for medical students.Citation7 Several studies have demonstrated the value of SDL for learning physiology and anatomy.Citation10,Citation11 SDL facilitates self-governance as well as decision-making and communication skills.Citation11,Citation12 Numerous studies have compared SDL to traditional lectures, with some of these studies demonstrating that self-learning groups achieved better results than groups who received lectures.Citation13–Citation15 Other studies have found no difference between SDL and traditional classroom teaching.Citation16–Citation19

Problem-based learning (PBL) has been adopted by many medical schools, and those schools have used a number of diverse instructional approaches. The primary approach is the construction of case-based scenarios and problems for small groups of students who discuss the scenarios and derive accurate solutions to the problems. A tutor or facilitator offers sympathetic supervision of the students. Discussions are structured to permit student-generated theoretical approaches to clarify problems associated with the scenario or case.Citation20 In this manner, students identify the limits of, or gaps in, their knowledge by recognition of the learning issues necessary to problem solution. Between individual group sessions, students investigate possible solutions to the problems. The students share their solutions and the results of their investigation at the next group session.Citation21,Citation22

PBL facilitates the student’s acquisition of appropriate attitudes and skills. It enriches their development of communication skills, comprising cooperation, teamwork, and appreciation of the views of others, and promotes interaction with group members.Citation21 Therefore, PBL is valuable for group education.Citation23 Prince et alCitation24 found that PBL enhanced attitudes and skills that promoted communication.

Barral and BuckCitation20 described PBL as an educational practice that is widely used in many medical school curricula. Although there are many PBL variants, PBL practice implies the presentation of problems that are case based to a small group of students who discuss the problems for two or more sessions. A tutor advocates and provides sympathetic guidance for the students. The problems are devised in a manner that permits students to create theoretical models to solve the problems within the context of the presented case-based scenario.

PBL has become fashionable in many medical schools that have advocated for curriculum improvement by adopting an integration-based curriculum instead of a system-based one. An integration-based curriculum promotes SDL; encourages in-depth learning and thinking; prepares students for lifelong learning; and improves retention of knowledge, more so than traditional courses.Citation9,Citation25

The medical school in the present study, Albaha School of Medicine (ABSM), adopted a fully integrated curriculum throughout the 6-year program, with the ophthalmology course implemented in the fifth clinical year. The learning objectives of the course were clearly defined and well structured, using taxonomy applied by Bloom and revised by Kress and Selander.Citation5 The objectives were formulated by a modular committee composed of ophthalmology experts. The teaching strategies and tools were closely linked to the course objectives. SDL was implemented by students who selected subject areas or themes based on cases or scenarios identified within the study guide module.

The aim of the study was to assess the effectiveness of SDL for instruction of ophthalmology. Furthermore, a comparison was made of the impact of SDL and PBL on ophthalmology teaching, when implemented for medical students in the fifth year of the clinical phase at ABSM.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study was approved by an ethical committee of ABSM, under the supervision of the Dean of Scientific Research and Quality as well as Accreditation Affairs. The committee approved and stated that “after investigation the proposal introduced by researchers to investigate the SDL vs. PBL in ophthalmology course, the committee agree to investigate the efficacy of SDL vs. PBL in the ophthalmology course as a part of a whole program evaluation without any funding” (ethical approval reference no. 211/2018). Furthermore, all students participating in the current study collectively provided written informed consent that implied their agreement to the research and investigation of a portion of their grades for SDL and PBL for both ophthalmology and the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) courses and to publish these data collectively in an anonymous form without individual detail.

At ABSM, the curriculum is a 6-year program. The academic years are divided into three phases: preparatory, basic, and clinical. The preparatory phase is the first academic year; the basic phase comprises the second and third years; and the clinical phase is the fourth, fifth, and sixth academic years. Each academic year has two levels (i.e. two semesters) arranged as follows: levels 1 and 2 forming the first academic year, levels 3 and 4 forming the second academic year, etc. The ophthalmology and ENT course are situated in the second semester of the fifth academic year, in Phase III, Level 9. In the preparatory phase, students study chemistry, biophysics, introductory courses for the basic sciences including pathology, innovation in medicine, and professionalism. In the basic phase, the students study a human body module, principle of disease, and systems-based basic modules or courses such as cardiovascular and respiratory. In the clinical phase, these courses are addressed and studied from a clinical perspective in addition to basic imaging, ophthalmology, ENT, and others. Each course is allocated credit hours and teaching strategy/tools. Ophthalmology and ENT are allocated two credit hours each and the courses are implemented in a 2-week period. The ophthalmology and ENT courses are in the second semester of the fifth academic year, in Phase III, Level 9 ().

Table 1 Mapping of the ophthalmology and ENT courses within the curriculum

This study was conducted with 60 male students enrolled in the ophthalmology course and representing the whole class of the fifth year, Phase III, and Level 9. At the time of the study, the students had completed the first five integrated modules adopted for that level, including the ENT course. All student grades for the ENT course were compared with the ophthalmology course for this study. The ENT course was selected as a control for the ophthalmology course in that the number of SDL and PBL is similar. Both courses are two credit units and of two weeks in duration, and are offered during the same year, level, and phase with the same number of questions posed for SDL/PBL.

The subjects for the study were selected and learning objectives designated for the ophthalmology course with four case-based scenarios adapted for both SDL and PBL. At the end of the SDL case scenario, guiding objectives were used to enable student identification of the differential diagnosis.

Methods

Preparation of SDL and PBL material

The content and learning objectives of the ophthalmology course were designed according to Bloom’s taxonomy. The teaching strategy and tools were selected for each objective. Some content and objectives were selected for PBLs and others for SDL. In PBL, the selection criteria were dependent on the presence of more than one factor with regard to pathogenesis, risk factors, differential diagnoses, laboratory investigations, radiological investigations, and treatments. In SDL, the criteria for selection were dependent upon genetic hypotheses and the rarity of the condition. These topics were not fully addressed by other teaching tools.

For SDL

The material for SDL was prepared by constructing two short case histories that covered the topic of ocular tumors. Each case was followed by learning objectives with the required references provided, which were derived from standard textbooks suggested at the beginning of the course. All 60 students completed SDL activities as a mandatory requirement for the course. The students read the scenario and discussed the learning objectives with the tutor and identified resources. Each group of ten students had a tutor who was a medical staff expert. The students investigated the case, undertook research, reported their findings, and discussed the case with their tutor, who provided continual guidance. At the conclusion of the course, a committee composed of staff experts discussed the case with each student separately, providing evaluation and feedback. A total of 15 questions related to the SDL activity were included in the final examination.

For PBL

The students were separated into five groups of 12 students each, with each group guided by a tutor. Two case-based scenarios were adopted. In the first session, the students discussed the case and addressed the learning objectives under the supervision of a tutor. In the second session, the students discussed their findings on case management and differential diagnosis. In the third session, all student groups were brought together as a single class. The tutors for all groups formed a committee that selected students (at least one student from each group) to deliver findings for each objective. This last session ensured that all learning objectives were delivered to all students in an equivalent manner by the end of the course. A total of 15 questions representing the PBL activity were included in the final examination.

The tutors selected for both SDL and PBL were staff medical experts from different departments. The tutors were trained by the medical education department through several workshops that specified the conduct of successful SDL and PBL as well as a description of the role of the tutor.

An example of PBL and learning objectives for the ophthalmology course are presented in Box 1.

An example of SDL and learning objectives for the ophthalmology course are presented in Box 2.

An example of PBL and learning objectives for the ENT course are presented in Box 3.

An example of SDL and learning objectives for the ENT course are presented in Box 4.

Assessment and statistical analysis

Thirty questions representing SDLs and PBLs were included in the final examination with 15 questions for each. The students answered these questions, and results were recorded with no negative marks applied. Comparisons were done by an independent sample t-test. For each tool, the student scores (maximum of 15) were categorized into high (score ≥13), moderate (score 11–12), low (score = 9, 10), and very low (score <9). A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. SPSS for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was utilized for data analysis.

Results

The answers for the 30 questions, 15 each for SDL and PBL, for the 60 students were as follows: With regard to the SDL component of the ophthalmology course, the number of students and the percentages were as follows: high scores in 10% (n = 6/60), moderate in 28.3% (n = 15/60), low in 38.3% (23/60), and very low in 26.6% (n = 16/60). For PBL, we observed high scores in 23.3% (n = 14/60), moderate in 33.3% (n = 20/60), low in 25% (15/60), and very low in 18.3% (n = 11/60) (). For the SDL component of the ENT course, the number and percentages were: high scores in 23.3% (n = 14/60), moderate in 28.3% (n = 17/60), low in 26.6% (n = 16/60), and very low in 21.6% (n = 13/60). For PBL, we observed high scores in 26.6% (n = 1 6/60), moderate in 28.3% (n = 17/60), low in 16.6% (10/60), and very low in 28.3% (n = 17/60) ( and ). A significant difference between SDL and PBL for the ophthalmology course was observed (p = 0.0094). Significant differences were observed between the two SDLs (p = 0.0308) and between the SDL of ophthalmology and the PBL of ENT (p = 0.03724) (). Further analysis of SDL and PBL against the total scores of students in the ophthalmology course demonstrated significant differences between students attaining 80–89% in SDL and PBL, between 70–79% for both SDL and PBL with p value =0.0196, and 0.01189, respectively ().

Figure 1 Student SDL and PBL scores for both the ophthalmology and ENT courses.

Table 2 Number and percentages of each group for SDL and PBL for both ophthalmology and ENT courses with statistical analysis by independent t-test

Table 3 Distribution of students according to their grades in SDL and PBL based on their total score in the ophthalmology course

Discussion

SDL has become a fundamental instructional modality for adult learning. In the health profession, SDL skills are linked to lifelong learning,Citation26 with such learning central to understanding advances in medical knowledge and improved innovations in patient care.Citation26

Based on data in , students enrolled in the SDL component of the ophthalmology course were deficient relative to those enrolled in PBL in the same course as well as its counterpart in the ENT course. A possible explanation is that students may consider the small number of SDL examination questions and the short duration of the course insufficient for adequate consideration and reading. These results are similar to those reported from a study by Murphy et alCitation27 who found that SDL is not an appropriate learning method for anatomy. Those authors found that student’s recall knowledge was derived from didactic lectures and not from reading about the subject.

Similar to the results herein, Pai et alCitation28 evaluated the effectiveness of SDL for first-year medical students divided into two groups – one that received lecture plus SDL on the same topic and another group that received lecture only. Ten multiple-choice questions evaluated whether there was a difference between the two groups for physiology learning, and no difference was found.

The PBL results of the ophthalmology course demonstrate the importance of PBL within the integrated curriculum – in particular, the ophthalmology course. These results are similar to many studies indicating the important role of PBL in adult learning and enhanced student performance.Citation9,Citation29

The results for SDL and other elements indicate that the delivery of SDL is problematic and needs reform. With regard to PBL, no significant difference between the ophthalmology and ENT courses was observed, with good student achievement in both courses. This identifies a gap between the SDL components of the two courses.

In the present study, analysis of ophthalmology scores for SDL and PBL revealed a significant p-value between the 80%–90% group (p = 0.0196) and the 70%–79% group (p = 0.01189) (). These results suggest that the weakest SDL achievement was observed in the majority of students. Further, in the high-scoring group, two students showed low and very low scores for SDL. This may be due to inappropriate SDL management in which student needs were not identified, learning objectives were not understood, or motivation was lacking for those students. Overall, these data demonstrate the need for SDL reform by the committee.

BlumbergCitation30 studied the effect of PBL on SDL and found that student involvement in PBL improved utilization of SDL skills. Some medical schools have identified particular courses within their curricula that are based on SDL activities in order to cultivate lifelong learning. Another study recommended that a primary goal for faculty is to encourage SDL among students in order to promote students’ lifelong learning and to enhance their skills.”Citation31

Shokar et alCitation32 assessed the degree of readiness for SDL in third-year medical students who participated in a PBL curriculum during the first 2 years of medical school. Students in this integrated medical curriculum were found to have good reading achievement through SDL that correlated with clinical performance. Those authors concluded that higher student achievement and readiness were achieved with SDL, which was associated with clinical clerkship scores and improved clinical skills. Others recommended that SDL be imbedded into the medical curriculum by formulating well-structured and staged courses.Citation33

GrowCitation33 advocated that SDL skills be purposefully integrated into the curriculum through a staged planning model.Citation16 Although SDL is strongly recommended for integration-based systems, Candy advised implementation in a systems-based approach.Citation26 It is worth noting that learners who have a deficiency in SDL experience are unable to master SDL skills or provide that experience for their stakeholders.Citation34

Concerning SDL, many suggestions have been made to improve the efficacy and effectiveness of teaching strategies such as SDL. These suggestions include clarification of learning objectives, periodic tutor driven discussions with students, the formation of small groups, panel discussions with the students about SDL themes, and identification of student learning styles.Citation35–Citation37 These suggestions have been implemented in courses with good results.

Conclusion

SDL is important for lifelong learning, especially in an integration-based curriculum. However, for this ophthalmology module, SDL did not promote self-readiness. Recommendations for improvement include instruction of more periodic small groups and panel discussions with the students.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BergmanEMSiebenJMSmailbegovicIde BruinABScherpbierAJvan der VleutenCPConstructive, collaborative, contextual, and self-directed learning in surface anatomy educationAnat Sci Educ20136211412422899567

- LeeYMMannKVFrankBWWhat drives students’ self-directed learning in a hybrid PBL curriculum?Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract201015342543719960366

- PremkumarKPahwaPBanerjeeABaptisteKBhattHLimHJDoes medical training promote or deter self-directed learning? A longitudinal mixed-methods studyAcad Med201388111754176424072133

- AinodaNOnishiHYasudaYDefinitions and goals of “self-directed learning” in contemporary medical education literatureAnn Acad Med Singapore200534851551916205831

- KressGSelanderSMultimodal design, learning and cultures of recognitionInternet High Educ2012154265268

- FindlaterGSKristmundsdottirFParsonSHGillingwaterTHDevelopment of a supported self-directed learning approach for anatomy educationAnat Sci Educ20125211412122223487

- HarveyBJRothmanAIFreckerRCEffect of an undergraduate medical curriculum on students’ self-directed learningAcad Med200378121259126514660430

- LyckeKHGrøttumPStrømsøHIStudent learning strategies, mental models and learning outcomes in problem-based and traditional curricula in medicineMed Teach200628871772217594584

- AttaISAlQahtaniFNHybrid PBL radiology module in an integrated medical curriculum Al-Baha Faculty of Medicine experienceJ Contemp Med Educ2015314651

- Arroyo-Jimenez MdelMMarcosPMartinez-MarcosAGross anatomy dissections and self-directed learning in medicineClin Anat200518538539115971224

- GrieveCKnowledge increment assessed for three methodologies of teaching physiologyMed Teach199214127321608324

- LakeDAStudent performance and perceptions of a lecture-based course compared with the same course utilizing group discussionPhys Ther200181389690211268154

- AbrahamRRUpadhyaSRamnarayanKSelf-directed learningAdv Physiol Educ200529213513615905163

- AbrahamRRFisherMKamathAIzzatiTANabilaSAtikahNNExploring first-year undergraduate medical students’ self-directed learning readiness to physiologyAdv Physiol Educ201135439339522139776

- GadeSChariSCase-based learning in endocrine physiology: an approach toward self-directed learning and the development of soft skills in medical studentsAdv Physiol Educ201337435636024292913

- PengWWSelf-directed learning: a matched control trialTeach Learn Med198917881

- HaidetPMorganROO’MalleyKMoranBJRichardsBFA controlled trial of active versus passive learning strategies in a large group settingAdv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract200491152714739758

- BradleyPOterholtCHerrinJNordheimLBjørndalAComparison of directed and self-directed learning in evidence-based medicine: a randomised controlled trialMed Educ200539101027103516178830

- FinleyJPSharrattGPNantonMAChenRPRoyDLPatersonGAuscultation of the heart: a trial of classroom teaching versus computer-based independent learningMed Educ19983243573619743795

- BarralJMBuckEWhat, how and why is problem-based learning in medical education?Annu Rev Biochem20131283435

- WoodDFABC of learning and teaching in medicine: problem based learningBMJ2003326738432833012574050

- OnyonCProblem-based learning: a review of the educational and psychological theoryClin Teach201291222622225888

- DolmansDHDe GraveWWolfhagenIHvan der VleutenCPProblem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and researchMed Educ200539773274115960794

- PrinceKJvan EijsPWBoshuizenHPvan der VleutenCPScherpbierAJGeneral competencies of problem-based learning (PBL) and non-PBL graduatesMed Educ200539439440115813762

- KilroyDAProblem based learningEmerg Med J200421441141315208220

- CandyPCSelf-Direction for Lifelong Learning: a Comprehensive Guide to Theory and PracticeSan Francisco, CAJossey-Bass1991

- MurphyKPCrushLO’MalleyEMedical student knowledge regarding radiology before and after a radiological anatomy module: implications for vertical integration and self-directed learningInsights Imaging20145562963425107581

- PaiKMRaoKRPunjaDKamathAThe effectiveness of self-directed learning (SDL) for teaching physiology to first-year medical studentsAustralas Med J201471144845325550716

- Chang BJ Problem-based learning in medical school: a student’s perspectiveAnn Med Surg (Lond)2016128889 eCollection 201627942381

- BlumbergPEvaluating the evidence that problem-based learners are self-directed learners: a review of the literatureEvensenDHHmeloCEProblem-Based Learning: a Research Perspective on Learning InteractionsMahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates2000199226

- SwansonAGAndersonMBEducating medical students. Assessing change in medical education – the road to implementationAcad Med1993686 SupplS1S46

- ShokarGSShokarNKRomeroCMBulikRJSelf-directed learning: looking at outcomes with medical studentsFam Med200234319720011922535

- GrowGTeaching learners to be self-directedAdult Educ Q199141125149

- DiazRMBerkLEA Vygotskian critique of self-instructional trainingDevelop Psychopathol199572369392

- AttaISAlQahtaniFNHow to adjust the strategy of radiopathologic teaching to achieve the learning outcomes?Int J Med Sci Public Health2018728691

- AttaISAlQahtaniFNMatching medical student achievement to learning objectives and outcomes: a paradigm shift for an implemented teaching moduleAdv Med Educ Pract2018922723329670415

- AttaISAlQahtaniFNAlghamdiTAMankrawiSAAlamriAMCan Pathology – teaching’ strategy be affected by the students’ learning style and to what extent the students’ performance be affected?Glo Adv Res J Med Med Sci2017611296301