Abstract

Purpose

To determine if video review of student performance during patient encounters is an effective tool for medical student learning.

Methods

Multiple bibliographic databases that include medical, general health care, education, psychology, and behavioral science literature were searched for the following terms: medical students, medical education, undergraduate medical education, education, self-assessment, self-evaluation, self-appraisal, feedback, videotape, video recording, televised, and DVD. The authors examined all abstracts resulting from this search and reviewed the full text of the relevant articles as well as additional articles identified in the reference lists of the relevant articles. Studies were classified by year of student (preclinical or clinical) and study design (controlled or non-controlled).

Results

A total of 67 articles met the final search criteria and were fully reviewed. Most studies were non-controlled and performed in the clinical years. Although the studies were quite variable in quality, design, and outcomes, in general video recording of performance and subsequent review by students with expert feedback had positive outcomes in improving feedback and ultimate performance. Video review with self-assessment alone was not found to be generally effective, but when linked with expert feedback it was superior to traditional feedback alone.

Conclusion

There are many methods for integrating effective use of video-captured performance into a program of learning. We recommend combining student self-assessment with feedback from faculty or other trained individuals for maximum effectiveness. We also recommend additional research in this area.

Introduction

There is a significant body of literature providing evidence that feedback is critical to effective learning.Citation1–Citation3 There is also significant evidence to support how, who, where, and when feedback should be provided,Citation4–Citation6 as well as different models of feedback.Citation6,Citation7 This is especially critical for formative feedback (designed to help learners improve performance)Citation2 versus summative feedback (informing learners, often through a grade, to show what learning objectives have been achieved).Citation8

More recent research strategies related to feedback and learning build upon previous theories and reveal increasingly complex approaches to considering and giving feedback. Studies link feedback with motivation,Citation9 perception/self-esteem (“face threat”),Citation10 perceptions and attitudes,Citation11 and self-reflection.Citation12 Researchers are also gathering evidence to support the notion that formative feedback can help students guide their own learning,Citation13 something they will need to be able to do if they are to be effective self-directed learners in their professional lives.

Formative feedback can be given to learners in “real time” or subsequent to testing/observation at a scheduled time. Sometimes the faculty member will review a test performance by going over test questions with the learner, providing more information than just a score. For performance-based feedback (eg, how the learner performed conducting an interview), video review has proven to be an excellent feedback resource since the 1960s.Citation14 The use of video makes feedback unique because it allows the learner to look at him/herself “from the outside,” thereby giving them a realistic perspective of their skills in context(s).Citation15,Citation16 Multiple dimensions of performance can be reviewed or assessed such as content (what is said), tone (how it is said), and non-verbal (body) language (eg, eye contact, body posture).Citation17 Using video as a feedback tool also precludes disagreement between the instructor and the learner over whether a particular behavior did or did not occur.

The literature linking formative assessment (feedback) with self-assessment has a lengthy historyCitation18 – some even believe that one of the primary goals of formative feedback is to help learners become more effective self-assessorsCitation19,Citation20 and self-regulated learners.Citation5 More and more, educators believe that formative feedback from the instructor, to be most effective, should be accompanied by self- and/or peer-assessment.Citation2 There is also evidence that self-assessment can significantly enhance learning.Citation21 While it is well understood that not all learners (or professionals, for that matter) are effective self-assessors,Citation22,Citation23 it also known that self-assessment is a skill that can be taught in a cycle of self-regulated learning that includes feedback from external sources.Citation24,Citation25

When video feedback first gained popularity, its primary value was felt to be the opportunity for “self-confrontation,” and so learners often viewed their performance in isolation.Citation26 Over time, however, video feedback has come to be viewed as more effective when combined with other forms of feedback or instruction, such as examples of desired behaviors or role modeling,Citation27,Citation28 or discussion between instructor and learner.Citation29 One study also reported that specifically understanding the expected behaviors (eg, a standard form to use when viewing performance) yielded considerably greater learning outcomes.Citation26 This form with specific behaviors constitutes a list of criteria by which learners can self-assess their performance. Without specific guidance, they might not see what they missed (“you don’t know what you don’t know”), or focus on some behavior that is irrelevant or inconsequential. Video can also provide concrete evidence of behaviors that might need improvement – since “the camera does not lie.”Citation16

Called by some “the gold standard of communication teaching,”Citation30 video feedback is now common in many professional higher education programs such as education, psychology, social work, nursing, and medicine. As technology for digitally capturing clinical performance has advanced dramatically in the last several decades, more studies involving video, feedback, self-assessment, and learning have been conducted in medical student education over the years. In this review article, we sought – through a structured and comprehensive analysis of the medical education literature – to answer the question: “Is video review of patient encounters an effective tool for medical student learning?”

Methods

Two of the authors (professional librarians [JL, ME]) searched multiple bibliographic databases to cover medical, general health care, education (general and medical), psychology, and behavioral science literature. A total of 19 databases were searched: Academic Search™ Premiere (1975–), AgeLine® (1978–), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (1987–), CINAHL® (1982–), Communication and Mass Media Complete™ (1915–), Computer and Information Systems Abstracts (1981–), ERIC (1966–), Education Full Text (1983–), Education Index Retro (1929–), Health Source®: Nursing/Academic Edition (1952–), Professional Development Collection™ (1930–), Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection™ (1930–), PsycINFO® (1887–), PubMed/MEDLINE® (late 1940s–), Sociological Abstracts (1952–), Sociological Collection™ (1975–), SPORTDiscus™ with Full Text (1930–), Teacher Reference Center (1984–), and Web of Science™ (1864–).

All searching was completed by September 19, 2011. Key search terms included: medical students, medical education, undergraduate medical education, education, self-assessment, self-evaluation, self-appraisal, feedback, videotape, video recording, televised, and DVD. Relevant terms from controlled vocabularies were used where available, such as MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) for PubMed, ERIC Thesaurus terms, and CINAHL Headings. Otherwise, combinations of textwords (ie, keywords) were used and supplemented with search features such as truncation. In addition, JL and ME examined the reference lists of the selected studies and review articles to identify any additional relevant articles.

A sample search for PubMed was:

(Students, Medical[mh] OR “medical students”[tiab] OR “Education, Medical, Undergraduate”[mh] OR “undergraduate medical education”[tiab]) AND (Videotape Recording[mh] OR Videotap*[tiab] OR DVD[tiab]) AND (Self-Evaluation Programs[mh] OR Self-Assessment[mh] OR “self assessment”[tiab] OR Self Efficacy[mh] OR Self Concept[mh] OR “self evaluation”[tiab]) AND English[la]

Selection criteria included limiting to English language literature, medical students (excluding residents, practicing physicians, and other health care professional students), the use of videotaping to record student–patient clinical interactions, and student viewing of his/her own videotape with particular focus on self-assessment as part of the feedback procedure. Videotape review by non-student independent raters was excluded unless students were also allowed to view the videotapes. Both group (peer) and individualized student viewing were included.

All initial abstracts were reviewed and duplicates were eliminated. Review articles were set aside for later examination of their reference lists. Abstracts that met the selection criteria (above) were brought to the full group of authors for a committee review. Citations that did not contain enough information to reach a clear decision regarding inclusion or exclusion without viewing the full-text were also sent to the full group for review. The full-text articles of the remaining citations were obtained, read, and discussed in a full committee review by all authors. Based on the complete article text, more citations were identified as not meeting selection criteria and were eliminated. The remaining articles were divided among three of the authors (MH, HM, CW) for detailed review. In addition, two of the authors (JL, ME) examined the reference lists of the selected studies and identified any additional relevant articles, which were subjected to a secondary review. Relevant studies identified were reviewed by the entire committee.

Results

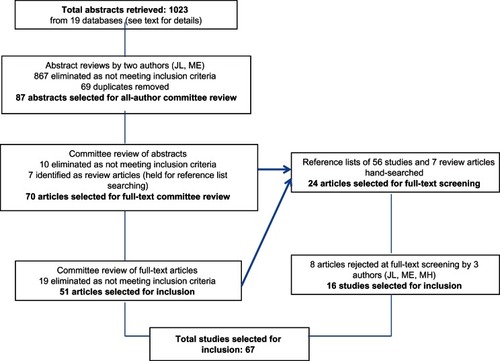

The initial searches yielded a total of 1023 abstracts, of which only 156 met the selection criteria (above). Another 69 duplicates were removed, leaving a total of 87 abstracts. The discussion of the entire committee eliminated another ten abstracts that did not meet selection criteria; seven were identified as review articles. All authors reviewed the full-text of the remaining 70 citations; 19 more citations were eliminated as not meeting selection criteria. Examination of the reference lists of the 52 selected studies and seven review articles yielded 16 more citations, resulting in 67 articles that were completely reviewed in detail ().

Of the 67 total studies that we examined in this review, there were 20 descriptive studies that described programs that used video technology in medical education, and 47 evaluative studies that specified quantitative outcomes. The first of these studies was published in 1968, and in the following four decades multiple studies from over 14 countries have been published. Many of the earlier studies used videos purely for summative purposes alone.Citation31–Citation35 In these studies, students were videotaped performing a patient interview, and then scored for specific interviewing criteria. Students were either given the option of reviewing their own videos independently, or the videos were reviewed in groups and individual settings with faculty discussion and feedback. The idea of using video to improve self-assessment has been widely described in many descriptive studies.Citation36–Citation41 Many of the descriptive studies also examined student satisfaction with using video review, and reported high student satisfaction rates with their programs.Citation42–Citation45

Among the evaluative studies, 17 were conducted in the preclinical years and 30 studies were conducted in the clinical years. There was great diversity in study design, number of students, type of encounter videotaped, and outcomes evaluated. The outcomes studied were student self-assessment, student satisfaction, feedback, faculty assessment, other assessment (often a simulated patient), and peer assessment. Most of the studies focused on communication skills, but some also looked at physical examination skills. A few studies examined technical skills such as wound closure and foley catheter placement,Citation46 and laryngoscopy.Citation47

Twelve of the 17 studies on preclinical students reported their outcomes on the use of video without the use of a control group (). All but three of these twelve studies reported that video review was a useful learning aid. The outcome that was evaluated in the majority of these studies was student interviewing skills which improved after video review.Citation48–Citation52 One study showed that student satisfaction with video review was initially very low, but improved tremendously after faculty education and development.Citation53 Two out of the three studies that reported that video was not helpful specifically looked at self-assessment skills. Medical students struggled with self-assessment, even with the aid of a video review of their performance. One study looked at students learning adult Basic Life Support skills, and the authors reported that even after video review, the students were not able to improve their self-assessment accuracy.Citation54 An older study that examined self-and peer-assessment of physical exam skills found that the students did not improve in either after video review.Citation55 The authors of this study postulated that perhaps students in their preclinical years had not yet developed the cognitive ability to perform self-and peer-assessments, given their lack of experience in these skill areas.

Table 1 Non-controlled studies during the pre-clinical years

Five of the 17 studies on preclinical students had a control group that was evaluated in comparison to a group that had the videotaped interaction (). All five of these studies reported that the video was a positive learning aid; four found that faculty feedback with use of the video was superior to traditional faculty feedback (without video review).Citation56–Citation59 One study examined how a video with a running commentary provided by a faculty member compared with face-to-face feedback.Citation60 This study demonstrated that students rated their satisfaction levels equally with video commentary compared to face-to-face feedback. This study also looked at student satisfaction with reviewing the video on their own, and reported that students had higher satisfaction rates with faculty review, either face-to-face, or with the running commentary on the video.

Table 2 Controlled studies during the pre-clinical years

Sixteen of the 30 studies performed with clinical medical students reported their outcomes without the use of a control group (). Fourteen out of these 16 studies reported that video review was a useful learning aid. Many of these studies reported high student satisfaction with video review.Citation61–Citation65 Two studies also reported an improvement in interviewing skills after video review and feedback.Citation33,Citation66 There were also studies that reported improvements of interviewing and physical exam skills after introduction of a curriculum that included video review, but also included other educational interventions that were not examined separately.Citation67–Citation69 Most of the studies videotaped students performing communication and/or physical exam skills, but one study videotaped students performing laryngoscopy, and reported that self-assessment skills improved after reviewing their video.Citation47 Of the two studies that reported that video was not helpful, one found that student satisfaction was higher with feedback from a standardized patient than with private review of the video themselves.Citation63 Of note, there was no specific feedback given to the student about their video. The other study that reported that video was not helpful was a smaller, older study that reported that four students had difficulty identifying the hidden agenda in simulated interviews even after video review.Citation70

Table 3 Non-controlled studies during the clinical years

Fourteen of the 30 studies performed with clinical medical students had a control group that was evaluated in comparison to a group that had the videotaped interaction (). Six of these studies looked specifically at video review with faculty feedback versus traditional faculty feedback, and all of them found video to be helpful.Citation71–Citation76 One study compared video review with feedback versus audio review with feedback, and found the former to be superior.Citation77 Another study compared video review with feedback to a reading and observation curriculum, and found the video intervention to be superior.Citation78

Table 4 Controlled studies during the clinical years

Data comparing outcomes after video review versus a traditional didactic curriculum were varied in the three controlled studies that examined this question. One study found that video review with feedback was superior when evaluating students’ ability to disclose cancer diagnoses to simulated patients.Citation79 Another study compared alcohol intervention skills in students who had received a traditional didactic curriculum to students who had received the same traditional didactic curriculum as well as video review of an interview and feedback, and found that there was no difference between the two groups.Citation80 Similarly, another study reported that students receiving a didactic curriculum on interviewing skills did as well as students who had video review and feedback.Citation81 Both of these studies discussed that this was a surprising finding – they expected the students in the video review cohort to perform better than the didactic curriculum students. Several studies commented specifically on the importance of faculty development and education in order for the video review and feedback to be effective for the students.Citation53

One controlled study looked at whether clinical students had improvement in their self-assessment skills after video review, and found an improvement.Citation82 Many of the clinical studies that did not include a control group showed a similar improvement in self-assessment after video review.Citation47,Citation66,Citation69 The earliest studies focused on faculty members providing feedback in conjunction with video review. Several studies reported that receiving feedback from a simulated patient was superior or equal to video review with a faculty member.Citation63,Citation83

Discussion

We know from research that formative feedback to students is an essential element of learning. Methods to provide the most effective feedback are constantly evolving, particularly for performance-based learning. The use of video as a tool for teaching and learning in medical education is appealing for many reasons cited above, and its use has progressed over time especially due to technological advancements that simplify the process. It has become much easier to record student performances and to share taped encounters with them for review. While most early studies focused on the video technology itself and students’ attitudes towards its use, more recently the attention has been on actual improvement in performance based on the wide use of video in medical student education.

There are a few review articles focused on the use of videotape analysis as an instrument for learning, but the reviews are not systematic or comprehensive. Findings were generally positive, even if occasionally it was difficult to determine which of the studies were actually evidence-based (some had limited details). Pinsky and WipfCitation84 cited a studyCitation85 showing that retention was drastically and significantly more positive for “showing and telling” (reviewing and providing feedback) than for showing alone or telling alone. When videotape review was linked with self-assessment, improved self-awareness and improved skills were documented.Citation66,Citation86 An older review by Hargie and MorrowCitation16 cited evidence in support of self-review as motivating, and as resulting in significant improvement in self-perception.Citation87 A comprehensive review of self-assessment in health professions education described studies with video review and self-assessment that were not necessarily consistent in terms of whether video review improved self-assessment accuracy.Citation88 Finally, a comprehensive review on teaching interviewing skills found that programs that incorporated structured feedback using videotape were more effective than those that utilized practice alone.Citation89

Although our review of older and more recent literature was generally positive, a wide range of study designs, methods, and outcomes was described, which made it challenging to reach specific generalizations about results. Studies had a large range of number of students included – some were clinical, some were preclinical. A variety of methods for including video in teaching and learning were described. These included taping the encounter for student review in the form of self-assessment, peer review in groups of students, faculty review with the student, simulated patient review with the student, or a combination of some or all of these techniques. Also, different outcomes were measured. Some included student satisfaction and attitudes, some included self-assessment, some included performance measures on the actual encounter, and others looked at performance measures on subsequent encounters. It was evident that video review with self-assessment alone was not effective because learners do not necessarily know what they don’t know. Guidance of some kind is necessary, whether it be feedback from peers and/or faculty (including standardized patients), a checklist of expected behaviors, or a “gold standard” performance against which students could measure their own performance.

While self-assessment is a critical skill for lifelong learning, it cannot be learned in a vacuum. Opportunities to self-assess in a cycle of goal-setting, external feedback, reflection, and adjustment must be integrated into learning opportunities. Students must understand why self-assessment is a key set of skills to master, and they must be given responsibility and accountability for teaching and learning to embed these skills into daily habits. E-portfolios are increasingly popular for these very reasons, especially when coupled with an opportunity for students to choose their “best” work (self-assessment), reflect on their development of knowledge and skills over time (reflection), and review this body of work with faculty mentors (external feedback).

Vital to this intentional integration of self-assessment into the curriculum is faculty development. To be most effective in providing feedback about performance and self-assessment accuracy, faculty must also possess a deep understanding of and commitment to helping students achieve self-assessment outcomes. Feedback to students must also be consistent, and based on specific program outcomes, to be most effective. Many faculty are committed to improving their own knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to teaching and learning, as evidenced by the growing number of professional development modules for faculty in medical schools (eg, weekly, year-long “medical education scholars” programs), as well the growing number of opportunities for health professionals to earn masters’ degrees in medical education.

This is also important because faculty development can play a critical role in medical education research. We commented above on the wide variety of study designs and subjects that described some form of video capture; there was a wide variety of study quality as well. Faculty participating in formal education related to teaching and learning can make significant contributions to the quality of future studies focused on tools and methods for teaching and learning, including those studies using video as an effective tool for learning and feedback.

Conclusion

After conducting such an extensive literature review, we can summarize several key points. Although not always specifically measured, authors generally reported positive outcomes when video-captured performance was used as a tool for learning, for self-assessment, and for feedback. And, although there were multiple study designs, the use of video-captured performance can foster self-reflection and self-assessment, both of which are key to lifelong learning. Finally, although we identified many studies, this field would benefit from additional, rigorous investigation. Multi-institutional studies would add significantly to the literature in this field.

From the findings of the many studies we reviewed, we are also able to make a recommendation as to specific steps educators can take when constructing curricula and/or studies involving the use of video-captured performance (). The answer to the original research question appears to be that when programs involving video-captured performance are designed effectively, video can be a powerful tool for learning.

Table 5 Recommended steps for effective use of video-captured performance

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BlackPWiliamDInside the black box: raising standards through classroom assessmentPhi Delta Kappan1998802139144

- FluckigerJVigilYPascoRDanielsonKFormative feedback: involving students as partners in assessment to enhance learningCollege Teaching2010584136140

- TangJHarrisonCInvestigating university tutor perceptions of assessment feedback: three types of tutor beliefsAssessment and Evaluation in Higher Education2011365583604

- GibbsGUsing assessment strategically to change the way students learnBrownSGlasnerAAssessment Matters in Higher EducationPhiladelphia, PASociety for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press19994156

- NicolDJMacfarlane-DickDFormative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practiceStudies in Higher Education2006312199218

- WilbertJGroscheMGerdesHEffects of evaluative feedback on rate of learning and task motivation: an analogue experimentLearning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal2010824352

- StarkRKoppVFischerMRCase-based learning with worked examples in complex domains: two experimental studies in undergraduate medical educationLearning and Instruction20112112233

- HarlenWJamesMAssessment and learning: differences and relationships between formative and summative assessmentAssessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice199743365379

- DweckCSSelf-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and DevelopmentPhiladelphia, PAPsychology Press1999

- WittPLKerssen-GriepJInstructional feedback I: The interaction of facework and immediacy on students’ perceptions of instructor credibilityComm Educ20106017594

- CanGWalkerAA model for doctoral students’ perceptions and attitudes toward written feedback for academic writingResearch in Higher Education2011525508536

- ChengGChauJDigital video for fostering self-reflection in an ePortfolio environmentLearning, Media and Technology2009344337350

- NixIWyllieAExploring design features to enhance computer-based assessment: learners’ views on using a confidence-indicator tool and computer-based feedbackBr J Educ Technol2011421101112

- AllenDWMcDonaldFJOrmeMEEffects of Feedback and Practice Conditions on the Acquisition of a Teaching StrategyCalifornia, CAStanford University1966

- FullerFFManningBASelf-confrontation reviewed: a conceptualization for video playback in teacher educationReview of Educational Research1973434469528

- HargieODMorrowNCUsing videotape in communication skills training: a critical review of the process of self-viewingMed Teach1986843593653586951

- HargieODicksonDTourishDCommunication Skills for Effective ManagementBasingstoke, Hampshire, NYPalgrave Macmillan2004

- OrsmondPMerrySFeedback alignment: effective and ineffective links between tutors’ and students’ understanding of coursework feedbackAssessment and Evaluation in Higher Education2011362125136

- BoudDSustainable assessment: rethinking assessment for the learning societyStudies in Continuing Education2000222151167

- SadlerDRFormative assessment and the design of instructional systemsInstructional Science1989182119144

- McDonaldBBoudDThe impact of self-assessment on achievement: the effects of self-assessment training on performance in external examinationsAssessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice2003102209220

- KrugerJDunningDUnskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessmentsJ Pers Soc Psychol19997761121113410626367

- DavisDAMazmanianPEFordisMVan HarrisonRThorpeKEPerrierLAccuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competenceJAMA20062969109416954489

- PintrichPRUnderstanding self-regulated learningNew Directions for Teaching and Learning199563312

- ZimmermanBJSchunkDHSelf-regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: Theoretical Perspectives2nd edMahwah, NJErlbaum2001

- FukkinkRPeer counseling in an online chat service: a content analysis of social supportCyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw201114424725121162662

- HosfordREJohnsonMEA comparison of self-observation, self-modeling, and practice without video feedback for improving counselor interviewing behaviorsCounselor Education and Supervision19832316270

- OrsmondPMerrySReilingKThe use of exemplars and formative feedback when using student derived marking criteria in peer and self-assessmentAssessment and Evaluation in Higher Education2002274309323

- LaurillardDRethinking teaching for the knowledge societyEDUCAUSE Review20023711625

- KurtzSSilvermanJDraperJChoosing and using appropriate teaching methodsKurtzSSilvermanJDraperJTeaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine2nd edOxford, UKRadcliffe Publishing200577103

- ConnollyJBirdJVideotape in teaching and examining clinical skills: a short case formatMed Educ1977114271275882034

- HolmesFFBakerLHTorianECRichardsonNKGlickSYarmatAJMeasuring clinical competence of medical studentsMed Educ1978125364368723688

- MenahemSInterviewing and examination skills in paediatric medicine: videotape analysis of student and consultant performanceJ R Soc Med19878031381423572942

- RuedrichSLGreinerCBEvaluation of medical-student clerks interviewing and mental status skills with a videotaped practical examinationJ Psychiatr Educ1988123212215

- StoeckleJDLazareAWeingartCMcGuireMTLearning medicine by videotaped recordingsJ Med Educ19714665185245162239

- BarrowsHSTamblynRMSelf-assessment unitsJ Med Educ19765143343361255692

- IrwinWGMcClellandRLoveAHCommunication skills training for medical students: an integrated approachMed Educ19892343873942770581

- MakoulGAltmanMEarly assessment of medical students’ clinical skillsAcad Med20027711115612431933

- McAvoyBRTeaching clinical skills to medical students: the use of simulated patients and videotaping in general practiceMed Educ19882231931993405113

- McManusICVincentCAThomSKiddJTeaching communication-skills to clinical studentsBMJ19933066888132213278518575

- RameyJWTeaching medical students by videotape simulationJ Med Educ196843155595634878

- Bonnaud-AntignacACampionLPottierPSupiotSVideotaped simulated interviews to improve medical students’ skills in disclosing a diagnosis of cancerPsychooncology201019997598119918865

- MeadowRHewittCTeaching communication skills with the help of actresses and video-tape simulationBr J Med Educ1972643173224677132

- NilsenSBaerheimAFeedback on video recorded consultations in medical teaching: why students loathe and love it – a focus-group based qualitative studyBMC Med Educ200552816029509

- VarkeyPEducating to improve patient care: integrating quality improvement into a medical school curriculumAm J Med Qual200722211211617395967

- KneeboneRKiddJNestelDAsvallSParaskevaPDarziAAn innovative model for teaching and learning clinical proceduresMed Educ200236762863412109984

- KardashKTesslerMJVideotape feedback in teaching laryngoscopyCan J Anaesth199744154588988825

- HoppeRBFarquharLJHenryRCStoffelmayrBEHelferMEA course component to teach interviewing skills in informing and motivating patientsJ Med Educ19886331761813346893

- HulsmanRLHarmsenABFabriekMReflective teaching of medical communication skills with DiViDU: assessing the level of student reflection on recorded consultations with simulated patientsPatient Educ Couns200974214214919062232

- TerasakiMRMorganCOEliasLMedical student interactions with cancer patients: evaluation with videotaped interviewsMed Pediatr Oncol198412138426700539

- WernerASchneideJMTeaching medical students interactional skills. A research-based course in doctor-patient relationshipN Engl J Med197429022123212374825853

- FarnillDHayesSCTodiscoJInterviewing skills: self-evaluation by medical studentsMed Educ19973121221279231116

- CassataDMHarrisIBBlandCJRonningGFA systematic approach to curriculum design in a medical school interview courseJ Med Educ19765111939942978707

- VnukAOwenHPlummerJAssessing proficiency in adult basic life support: student and expert assessment and the impact of video recordingMed Teach200628542943416973455

- CalhounJGWoolliscroftJOTenhakenJDWolfFMDavisWKEvaluating medical student clinical skill performance. Relationships among self, peer, and expert ratingsEval Health Prof1988112201212

- DavisJCDansPEThe effect on instructor-student interaction of video replay to teach history-taking skillsJ Med Educ198156108648667288854

- MorelandJRIveyAEPhillipsJSAn evaluation of microcouseling as an interviewer training toolJ Consult Clin Psychol19734122943004747942

- OzcakarNMevsimVGuldalDIs the use of videotape recording superior to verbal feedback alone in the teaching of clinical skills?BMC Public Health2009947420021688

- ShavitIPeledSSteinerIPComparison of outcomes of two skills-teaching methods on lay-rescuers’acquisition of infant basic life support skillsAcad Emerg Med201017997998620836779

- KirbyRLRunning commentary recorded simultaneously to enhance videotape as an aid to learning interviewing skillsMed Educ198317128306823217

- Del MarCIsaacsGTeaching consultation skills by videotaping interviews: a study of student opinionMed Teach199214153581608329

- EllisonSSullivanCQuaintanceJArnoldLGodfreyPCritical care recognition, management and communication skills during an emergency medicine clerkshipMed Teach2008309–10e228e23819117219

- SharpPCPearceKAKonenJCKnudsonMPUsing standardized patient instructors to teach health promotion interviewing skillsFam Med19962821031068932489

- ShepherdDHammondPSelf-assessment of specific interpersonal skills of medical undergraduates using immediate feedback through closed-circuit televisionMed Educ198418280846700451

- WagstaffLSchreierAShuenyaneEAhmedNTelevised paediatric consultations: a student evaluation of a multipurpose learning strategyMed Educ19902454474512215298

- LaneJLGottliebRPImproving the interviewing and self-assessment skills of medical students: is it time to readopt videotaping as an educational tool?Ambul Pediatr20044324424815153057

- KraanHFCrijnenAAde VriesMWZuidwegJImbosTVan der VleutenCPTo what extent are medical interviewing skills teachable?Med Teach1990123–43153282095449

- Simek-DowningLQuirkMELetendreAJSimulated versus actual patients in teaching medical interviewingFam Med19861863583603556894

- WhiteCBRossPTGruppenLDRemediating students’ failed OSCE performances at one school: the effects of self-assessment, reflection, and feedbackAcad Med200984565165419704203

- MenahemSTeaching students of medicine to listen: the missed diagnosis from a hidden agendaJ R Soc Med19878063433463625687

- BrownJEOsheaJSImproving medical student interviewing skillsPediatrics19806535755787360547

- RutterDRMaguireGPHistory-taking for medical students. II-Evaluation of a training programmeLancet19762798555856060633

- SchreierADubBTeaching interpersonal communication skills in paediatrics with the help of mothersS Afr Med J198159248658667233310

- StillmanPLSabersDLRedfieldDLUse of paraprofessionals to teach interviewing skillsPediatrics1976575769774940718

- StillmanPLSabersDLRedfieldDLUse of trained mothers to teach interviewing skills to first-year medical students: a follow-up studyPediatrics1977602165169887330

- StoneHAngevineMSivertsonSA model for evaluating the history taking and physical examination skills of medical studentsMed Teach198911175802747487

- MaguirePRoePGoldbergDJonesSHydeCOdowdTValue of feedback in teaching interviewing skills to medical studentsPsychol Med197884695704724878

- QuirkMBabineauRATeaching interviewing skills to students in clinical years: a comparative analysis of three strategiesJ Med Educ198257129399417143406

- SupiotSBonnaud-AntignacAUsing simulated interviews to teach junior medical students to disclose the diagnosis of cancerJ Cancer Educ200823210210718569245

- WalshRASanson-FisherRWLowARocheAMTeaching medical students alcohol intervention skills: results of a controlled trialMed Educ199933855956510447840

- MasonJLBarkleySEKappelmanMMCarterDEBeachyWVEvaluation of a self-instructional method for improving doctor-patient communicationJ Med Educ19886386296353398018

- SrinivasanMHauerKEDer-MartirosianCWilkesMGesundheitNDoes feedback matter? Practice-based learning for medical students after a multi-institutional clinical performance examinationMed Educ200741985786517727526

- LevenkronJCGreenlandPBowleyNUsing patient instructors to teach behavioral counseling skillsJ Med Educ19876286656723612728

- PinskyLEWipfJEA picture is worth a thousand words: practical use of videotape in teachingJ Gen Intern Med2000151180581011119173

- DwyerFMStudent’s Manual: Designed to Accompany Strategies for Improving Visual LearningState College, PALearning Services1978

- HaysRBTeaching health promotion and illness prevention to trainee general practitionersMed Teach19911332232261745112

- TuttleRLThe Effects of Video Tape Self Analysis on Teacher Self Concept, Effectiveness, and Perceptions of StudentsChapel Hill, NCUniversity of North Carolina1972

- GordonMJA review of the validity and accuracy of self-assessments in health professions trainingAcad Med199166127627691750956

- CarrollJGMonroeJTeaching clinical interviewing in the health professionsEval Health Prof1980312145

- FarnillDTodiscoJHayesSCBartlettDVideotaped interviewing of non-English speakers: training for medical students with volunteer clientsMed Educ199731287939231107

- RudyDWFejfarMCGriffithCHIIIWilsonJFSelf-and peer assessment in a first-year communication and interviewing courseEval Health Prof200124443644511817201

- ZickAGranieriMMakoulGFirst-year medical students’ assessment of their own communication skills: a video-based, open-ended approachPatient Educ Couns200768216116617640843

- GoldschmidtRHHessPATelling patients the diagnosis is cancer: a teaching moduleFam Med19871943023043622979

- CushingAMJonesAEvaluation of a breaking bad news course for medical studentsMed Educ19952964304358594407

- PaulSDawsonKPLanphearJHCheemaMYVideo recording feedback: a feasible and effective approach to teaching history-taking and physical examination skills in undergraduate paediatric medicineMed Educ19983233323369743791

- MyungSJKangSHKimYSThe use of standardized patients to teach medical students clinical skills in ambulatory care settingsMed Teach20103211e467e47021039087

- ScheidtPCLazoritzSEbbelingWLFigelmanARMoessnerHFSingerJEEvaluation of system providing feedback to students on videotaped patient encountersJ Med Educ19866175855903723570

- ClarkDRBloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains2010 Available from: http://www.nwlink.com/∼donclark/hrd/bloom.htmlAccessed November 5, 2011