Abstract

The advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) role first developed in the USA in the 1960s in primary care. Since then, it has evolved in many different countries and subspecialties, creating a variety of challenges for those designing and implementing master’s programs for this valuable professional group. We focus on ANPs in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care setting to illustrate the complexity of issues faced by both faculty and students in such a program. We review the impact of limited resources, faculty recruitment/accreditation, and the relationship with the medical profession in establishing a curriculum. We explore the evidence for the importance of ANP role definition, supervision, and identity among other health professionals to secure a successful role transition. We describe how recent advances in technology can be used to innovate with new styles of teaching and learning to overcome some of the difficulties in running master’s programs for small subspecialties. We illustrate, through our own experience, how a thorough assessment of the available literature can be used to innovate and develop strategies to create an individual MSc programs that are designed to meet the needs of highly specialized advanced neonatal and pediatric nursing practice.

Introduction

The advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) role first developed in the USA in the 1960s. Initially, the role was developed to improve service delivery and access in primary care pediatrics; however, this narrow focus quickly expanded to include a variety of settings and populations.Citation1 More recently, APRNs have had to face the challenge of declining numbers in a difficult economic environment, and even hostile campaigns from US-based physician organizations.Citation2 While the majority of APRNs working with children are in ambulatory pediatric settings, certain subspecialty areas have been particularly successful at developing an advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) role in the current climate – most notably in neonatal and pediatric intensive care. The advanced neonatal nurse practitioner (ANNP) role was first developed in the 1980s, primarily to provide care for critically ill infants in an intensive care setting. The role has been formally endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.Citation3 This included recognition of the training and credentialing process, and acknowledged the requirement for completion of a master’s-level education program in the neonatal nursing specialty. In 2009, there were 46 nurse practitioner programs in the USA that offered a neonatal training pathway.Citation4 While the acute care advanced pediatric nurse practitioner (APNP) role has been a little slower to develop than the APNP role in primary care, it is now well established,Citation5 and specific pediatric intensive-care nurse practitioner programs have been successfully implemented.Citation6

The advanced nursing practice model has been adopted by other countries. The ANNP role is well established in Canada.Citation7 The first UK ANNP master’s program was introduced in 1992.Citation8 It is now estimated that there are more than 250 qualified ANNPs, with many more now in training.Citation9 The UK APNP role is also well recognized, but has been established for a much shorter time, so the role is in a much earlier stage of development.Citation10 The implementation of advanced nursing practice roles in both AustraliaCitation11 and New ZealandCitation12 in the late 1990s involved careful evaluation of overseas experience, especially in North America. The potential benefits for pediatric and neonatal critical care have been identified.Citation13,Citation14 There are currently 24 countries that have adopted the advanced nursing practice model.Citation15

International recognition of the ANP role has been accompanied by growing evidence that in the field of critical care (adult, pediatric, and neonatal), substantial positive outcomes have been achieved for patient care, service delivery, and advanced nursing.Citation14 Nevertheless, the training programs for both ANNPs and APNPs face considerable threats and challenges. We felt that our process of course design would be facilitated by a review of the issues facing all those charged with developing an ANP MSc program in a small clinical subspecialty. The current evidence base comprises many qualitative studies (often based on very small numbers) providing a student perspective but no strategic overview for the course designer. We have identified the faculty, clinical, professional, student, and educational factors that influence curriculum design. We have summarized the issues in . We use our own experience with the Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) Advanced Paediatric/Neonatal Nurse Practitioner MSc program to illustrate how these factors can influence course development. The neonatal modules of this course are hosted by the Liverpool Women’s Hospital, and that course’s development is used as an example of how one host institution can support a program for ANP students from many other institutions training in the same subspecialty. Our review focuses on the particular challenges associated with subspecialty – advanced nurse practice training – using neonatal and pediatric intensive care as an example. However, many of the challenges described apply to other subspecialty MSc training programs.

Table 1 Summary of the issues affecting course design for advanced nursing practice MSc programs

Viability of university master’s programs

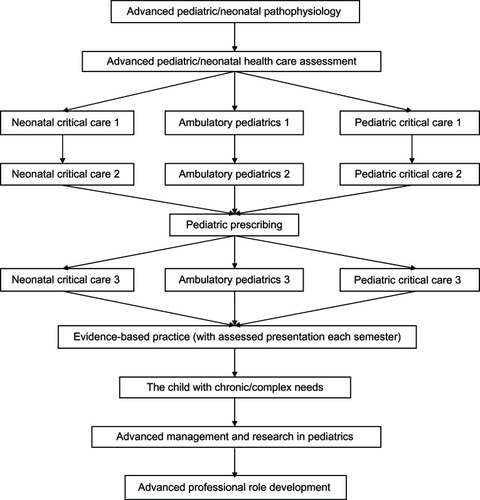

In challenging economic times, higher education programs are particularly vulnerable to limitations in resources. This makes it difficult to maintain the low-volume, high-cost programs associated with relatively small subspecialties such as neonatal and pediatric critical care. One approach is to accept a more general pediatric ANP accreditation and put in place a local program to adapt postgraduate clinical skills to meet the service need.Citation16 Our own approach has been to develop a combined APNP program with three pathways (): ambulatory pediatrics, pediatric critical care, and neonatal critical care. This modular design allows the foundation skills to be taught to all pathways (eg, pediatric/neonatal physiology, evidence-based medicine, pediatric prescribing, pediatric/neonatal health assessment), thus increasing the student numbers for these modules and enhancing course viability. Student practitioners can then pursue the specialist pathway to obtain the most relevant accreditation. Student numbers in the specialty modules may be small, but this allows for close clinical mentorship in the local clinical environment. In addition, this model can incorporate additional superspecialist content (eg, pediatric, neonatal, transport) or new pathways (eg, pediatric oncology, nephrology). This approach aims to foster a collective APNP professional identity and help prevent the isolation newly qualified APNPs can feel, particularly if they are the first in their local service (see below).

Shortage of ANPs and educators

In the USA, attention has recently been drawn to a shortage of ANPs willing to serve in faculty roles. Constrained budgets often make higher-education salaries less competitive than those in clinical practice.Citation2 In 2004, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing decided that the terminal degree for all nurse practitioners should move from the master’s degree to that of Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) by 2015.Citation17 As many schools of nursing move to the DNP degree, existing advanced-practitioner faculty without a doctorate may find themselves underqualified.Citation18 In the neonatal intensive care setting, the problem is particularly acute because of the very short supply of ANNPs. The high cost of ANNP education is reducing the number of available NNP programs, and those remaining are not graduating a sufficient number of new ANNPs to keep up with demand.Citation19 Given ANNP shortages, even at the master’s level, the DNP is likely to lead to further ANNP program closures because of faculty shortages.Citation20 The shortage of ANNPs is also a problem in the UK,Citation9 and although faculty shortages are an issue, this is partly offset by the role of consultant neonatologists in delivering the ANNP programs. This makes sense, as even in the USA, most ANNPs work under the supervision of consultant neonatologists.Citation21 The LJMU MSc program has taken this one step further and integrated the ANNP program’s neonatal modules with the postgraduate medical-education program for neonatology. Not only does this have economic benefits, but it also has other potential advantages relating to professional identity, hierarchies, and the perception of ANNP by doctors (see below).

The ANP role

In order to develop and sustain an advanced nursing practice master’s program, there has to be clarity about the professional’s role. This is not straightforward, as the role has evolved rapidly and continues to change. Even in a subspecialty as specific as pediatric or neonatal intensive care, there is a wide variety of roles in clinical practice.Citation22,Citation23 Although most provide clinical expertise in the intensive care environment, UK ANNPs have developed other models of care, including local lead practitioners in small stand-alone unitsCitation24 or practitioner-led transport and retrieval services.Citation25 A small number of ANNPs in the USA have developed a community-based role outside the intensive care environment.Citation21 This process of evolution requires programs that are adaptable; this flexibility is facilitated by a modular curricula structure, with modules common to several training pathways. However, education programs also need to equip ANPs with the tools and professional skills to adapt to new service needs and opportunities within a rapidly changing health care market.

Unfortunately, much of the demand for ANNPs and APNPs in the UK, Europe, and other countries is not driven by the desire to create a clear professional role but by the need to fill service gaps left by medical staff. These situations have become more common in many countries, following the implementation of statutory limits on junior doctors’ working hours (for example the European Working Time Directive). This means seconding units may have quite specific requirements for student ANNPs when they qualify, and these may involve joining a medical rota comprising junior doctors at a particular grade, rather than developing a distinct and complementary professional role. The importance of role ambiguity has been recognized by Lloyd Jones,Citation26 with ambiguity increasing when the post-holder or other stakeholder is unclear about his or her conception of the role, or holds different ideas for its implementation. In some cases, this can lead to unrealistic expectations for the role and a view that nurse practitioners are an instant solution to the immediate service needs of their respective institutions.Citation27 Role incompatibility generally arises when stakeholders hold clear, well-known, and incompatible expectations of a role. This can lead to conflict if ANPs’ expectations of the role come second to those of medical staff and managers.Citation27 Filling service gaps does not equate to a sustainable career pathway and often leads to disillusionment with a post and to ANNPs leaving their original unit or the profession. It is therefore vital that APNP and ANNP master’s programs develop a relationship with seconding units to ensure that there is congruence between the advanced practitioner’s vision for the role and that of the organizational decision makers. It is also imperative that the clinical support required during training be sustained after qualification.

Role transition for ANPs

Role transition is never easy, but is complicated by the experienced neonatal nurse’s frustration with reverting to a student role and becoming a novice practitioner, sometimes after years of developing a reputation as an expert nurse.Citation28 Common to all advanced practice transitions are stages similar to those Benner identifies in her novice-to-expert theory of nursing practice.Citation29 In their former staff nursing roles, ANNPs have previously gone through the novice-to-expert process as defined by Benner, yet they are required to repeat this process in almost a counterintuitive way. Benners’ five stages of the journey from novice to expert are perhaps the best description of the role-transition for the emerging novice ANNP.Citation29 The insecurities and self-doubt, either obvious or hidden, are well documented, in that most new ANNPs will experience this at the beginning of their career. Feelings of frustration and inadequacy are common during one’s first year as an ANNP.Citation28 Studies focusing on role transition and role development suggest that a strong nursing identity is important for success in the ANNP practice environment. Other studies have explored in some depth the emerging ANNP’s conflicts, barriers, and relationship issues within the multidisciplinary team.Citation26 Participants of our study were often anxious about the integration of theory and practice, while successful transition appeared to depend on the following factors: confidence, enthusiasm, clinical support, and opportunities to acquire practical skills.

ANNPs functioning at the novice level relied heavily on protocols and guidelines. However, guidelines are not a substitute for expert clinical judgment and assessment of the individual patient; the ANNP’s moving through the stages toward expert practice requires the use of experiential, intuitive judgment.Citation30 In their study, Lyneham et alCitation31 describe the journey from novice to expert in the following terms: knowledge, experience, connection, feeling, syncretism, and trust. All of these factors must be considered by service providers, educators, and the students themselves, both during training and during their transition, after qualification.

The journey from novice-to-expert advanced practitioner is not completed within the time frame of the MSc program. Indeed, the first year after qualification can be the most challenging, as there is usually no mechanism for other health professionals to identify one’s level of experience. The process of re-attaining expert status has been described as having four themes:Citation32

The ambivalence novice ANNPs experience regarding their preparedness for the role.

The feelings of anxiety, insecurity, exhaustion, and lack of confidence during transition.

The 1-year mark as a significant time frame for feeling like a real ANNP.

Vulnerability of the novice ANNPs to harsh criticism and the importance of support.

To an extent, the role transition depends on the demographics of the student population. In the early stages of ANP role implementation within a particular country or specialty, students tend to be very experienced nurses who want to continue to develop in a clinical role. While transition may be greatly enhanced by the confidence that comes with clinical expertise, the return to novice status and the entrenched thinking and practice that comes with long experience in a clinical role can be a barrier (as described above). Once the role becomes established, students make the career choice to become an ANP much earlier in their nursing career, with increasing numbers identifying it as their chosen path beyond obtaining their nursing degree. While these nurses have less clinical expertise, their recent exposure to new methods of learning, and the presence of established ANPs in their institution are advantages in role transition.

At our own clinical site (Liverpool Women’s Hospital), we have recognized the difficulties associated with the first-year post-qualification and introduced a “probationary” year, where the newly qualified ANNP (following a 1-year MSc program) worked alongside colleagues in a supernumerary capacity and gradually took on working independently at a pace to suit their individual needs. This probationary year was not included in the 1-year MSc programs available before 2008, and was a post-qualification innovation unique to Liverpool Women’s Hospital. All practitioners rapidly achieved some degree of working independently within a few months, whereas during more-isolating shifts (evenings and nights), the transition to more independent practice took longer. Unsurprisingly, this strategy met regular resistance from management. However, without this additional support, failure of transition is more likely and ultimately more costly. During the development of the LJMU MSc program (in 2008), we designed the curriculum to include a probationary year, allowing the students to spread the modules over 2 years, but with the second year dominated by progress toward integrated and independent clinical practice. The MSc was then awarded after 2 years, when the practitioner felt confident in their professional identity.

Other professionals’ perceptions of the ANP role

Relationships with other health care professionals are crucially important to the success of advanced-practice roles. Lack of support is associated with isolation that leads to anxiety and stress. This is particularly important when the role is new to the service or organization. A review of clinical staff perceptions of a new APNP role in pediatric intensive care revealed little consensus about essential roles and responsibilities.Citation33 This confusion extended to educational, mentorship and qualification requirements risking the role ambiguity described earlier. A survey of UK clinicians’ perceptions of the ANNP role revealed some interesting differences. Clinicians identified ANNPs with more procedure-orientated roles (eg, cannula and line insertion), and they were less likely to view taking case loads, conducting ward rounds, or accepting outside referrals as integral elements of the ANNP role.Citation34 In a survey of ANNPs with a range of expertise,Citation35 those with more experience and confidence frequently reported increased interprofessional role confusion or conflict with junior doctors, and with some consultants, particularly where there were only one or two ANNPs in the neonatal team.

Given that the earliest roles for practitioners involve primary care and nonacute hospital presentations, it is interesting that in one survey the ANP was perceived more positively by medical and nursing staff in emergency care settings than by primary care physicians.Citation36 This may reflect either confusion over ANP roles or the fact that close working relationships and mutual respect are easier to generate in emergency and intensive care settings than in primary care settings. It has also been suggested that ANPs may improve the doctor–nurse relationship within a clinical service, although no measurable change was identified when this was evaluated in an Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) setting.Citation37 It is clear that suboptimal professional and managerial relationships can create a significant barrier to ANP role development, and of these, the support of nursing colleagues is the most crucial.Citation26

The integration of the neonatal modules within the LJMU MSc program with postgraduate medical education for trainee pediatricians has economic advantages, but also plays an important part in role perception and working relationships. The establishment of medical–nursing relationships during training forms the foundation for effective and mutually respectful interdisciplinary relationships in the work environment. Shared case-based presentations (bedside and classroom), evidence-based practice, and simultaneous acquisition of clinical skills provide a common ethos of communication and collaboration. This has the potential to reduce the risk of future role conflicts that can complicate the workplace for nursing roles that adopt medical–clinical skills, particularly given the differences in undergraduate training pathways for doctors and nurses.

Trainers, mentors, and supervision

The challenges of recruiting and sustaining a faculty for an advanced nursing-practice master’s program were identified earlier. The implications of the DNP have been discussed. The need for research to identify effective strategies for recruiting, preparing, and supporting preceptors in their roles has been recognized.Citation38 It is clear that ANP roles require a unique blend of supervision and mentoring from both the medical and nursing professions. ANPs have an ambiguous relationship with medicine, because they have been dependent on medical mentorship to develop clinical skillsCitation39 and they are now occupying roles traditionally associated with medical practice. Consequently, NPs challenge professional boundaries and present particular concerns to their medical mentors. This can result in a conflicting experience of promoting a clinical role that challenges traditional medical authority.Citation38 This renegotiation of professional boundaries is easier where strong multidisciplinary work is an integral part of the specialty, as it is in pediatrics. In some cases, the medical model of training has been recognized in a clinical internship paradigm.Citation40 This allows the student ANP to complete training with a suitably qualified mentor, which requires them to work together to develop and maintain a clinical plan, keep a weekly log, and monitor the achievement of learning objectives. Lack of role models and mentors, particularly in the early phase of ANP establishment in an institution have been identified by ANPs as barriers to effective practice.Citation26

In the pediatric/neonatal ICU context, the supervision and mentoring process includes classroom and bedside teaching, senior medical and advanced nursing practice mentorship, and a shared learning experience with junior medical trainees. Clearly supervised clinical practice is a key part of any advanced practice program,Citation41 and the intensive care environment creates unique challenges in this respect. Neonatal nursing educators must constantly monitor clinical practice and reevaluate the curriculum to ensure that the necessary knowledge and skills for successful practice can be achieved for the educational program.Citation42

Supplementation of formal generic qualifications is required for specialty programs where student numbers are small (as in pediatric subspecialties). The additional training can take the form of in-house apprenticeships, education, and job-specific training.Citation43 Such approaches can be of variable quality and consistency, can result in a lack of academic credibility, and can impair career advancement. Nevertheless, local programs for APNPs to enhance generic, pediatric advanced-practice qualifications have been successful. The alternative strategy, employed by the LJMU MSc program, is to share modular teaching to ensure academic standards are maintained and to provide oversight and consistency to local “apprenticeship” training in terms of subspecialist content.

The integration of the LJMU MSc program’s neonatal modules with postgraduate medical education for trainee pediatricians is also important for role definition. Student ANNPs share formal-classroom education programs (delivered by consultant neonatologists and other relevant specialists) and work alongside the same trainee pediatricians to acquire clinical and practical skills at the patient’s bedside. This apprenticeship is directly supervised by experienced ANNPs and mid-grade pediatric trainees. Incorporating senior ANNPs in residents’ teaching has been successfully introduced in other neonatal intensive care units.Citation44 It provides appropriate professional role models for student ANNPs and helps clarify the hierarchy of clinical experience for pediatric trainees, some of whom may not be familiar with the ANNP role.

Nonmedical prescribing

The importance of prescribing to maximizing ANP potential in patient care was recognized when the role was introduced in IrelandCitation45 and New Zealand.Citation46 The inability to prescribe is a threat to the development and progress of autonomous practice. One of the major frustrations for ANNPs in the UK has been restrictions on prescribing practice,Citation23 where only half of ANNPs in this survey were able to order medication, most within patient group directions (a clearly defined prescribing process related to a specific drug or condition). More recently, this has been addressed with a framework of accreditation for nonmedical prescribers (NMPs), leading to stand-alone university modules that allow existing ANNPs to become NMPs. However, many of these courses are generic and do not deal with the very specific prescribing issues for neonatal and pediatric practice in an intensive care setting.

Off-license and unlicensed medications also present a challenge for the nurse-prescriber in pediatric/neonatal practice.Citation47 A specific focus on pediatric pharmacology and pharmacokinetics in a prescribing course is essential. Once a pool of nurse-prescribing expertise has been developed in a specialist area (eg, pediatric/neonatal intensive care) this can provide a supportive frame for junior medical trainees.Citation47 This improved continuity has potential benefits for patient safety, given that ANPs have a nursing background that gives them greater insight into the risks of administration errors and their relationship to poor prescribing practice.

The LJMU program incorporates a stand-alone nonmedical-prescribing module that includes additional content on pediatric and neonatal pharmacology; it is requisite for NMPs working with these specialist populations. The module is common to the three training pathways and achieves specific prescribing competencies using case-based examples and the development of a practical prescribing framework that meets the needs of the respective specialist areas. The stand-alone status also allows qualified pediatric/neonatal practitioners without NMP status to obtain this important qualification.

Curriculum structure

The complexity of the evolving ANP role demands new teaching strategies. Based on the challenges that clinicians face daily, one teaching–learning strategy describes the need to address 5 central learning issues:Citation48

Identifying clinical priorities.

Solving clinical problems by understanding the clinical context.

Developing clinical reasoning during role transition.

Developing an ethical framework for decision making.

Taking appropriate professional responsibility for clinical judgments.

Although these five central issues are typically excluded from classic academic approaches, they are addressed by the “Thinking-in-Action” approach.Citation48 This teaching–learning strategy offers a different way of teaching clinical judgment that closely resembles the way in which expert nurses actually think and reason in patient situations as they unfold.

The goal in developing an advanced practice curriculum is to identify practice knowledge and skills common to all advanced practice nurses and to differentiate between the common and specialist content necessary to support clinical expertise and designated areas of practice.Citation49 The LJMU program embraces this concept with three (and potentially more) subspecialist training pathways sharing common pediatric professional modules. Fundamental to the achievement of this objective are innovative and critically reflective curriculum design skills.Citation50 Establishing and maintaining high quality curricula is crucial, as advanced nursing practice students must gain skills that are far beyond anything learned or done previously as a registered nurse.Citation51 The curriculum must also address the consolidation and transition issues described earlier.

Determining the theoretical knowledge content of a program is relatively straightforward. Defining advanced practice competencies is far more problematic.Citation45 These competencies must confirm expert clinical practice, but must also include clinical and professional leadership, ethical decision-making skills, education, and training and guidance skills. The broader professional skills of evidence-based practice, clinical governance, auditing, and research are likewise key components of students’ future role and must be established themes within any curriculum. It is important that all curricula also address the wider, national strategic issues relating to advanced nursing practice. This will involve collaboration between employers, commissioners, and educators.Citation52

As with medical education, the problem-based learning approach can be directly applied to professional advanced nursing practice, thereby providing the student with the skills needed for clinical decision making from a holistic viewpoint.Citation53 This approach does not have to exclude traditional classroom teaching: the LJMU master’s program follows up traditional classroom lectures with themed problem-based learning sessions to encourage the deeper learning required for advanced clinical practice.

Learning tools

Nursing programs have traditionally been content-driven, but the rapidly changing health care environment requires a radical transformation in curricula, teaching, and learning.Citation54 MSc programs in advanced nursing practice are required, to develop more-sophisticated critical-thinking abilities than those covered by basic degree qualifications; this is because of the nature and practice of the advanced nursing role. Nevertheless, achieving educational and professional competencies in a clinical health care setting is a challenge. While problem-based learning is one key approach (see above), a single educational strategy is unlikely to meet the diverse learning styles of ANP students; fortunately, evolving educational technology can allow far more flexibility in meeting different student learning styles. Simulation and the use of scripted case histories are increasingly recognized for their ability to enhance critical thinking and practical skills. In addition, a clinical simulation can promote effective communication skills, thereby facilitating team-building and development using multidisciplinary scenarios.Citation55

Distance learning helps create opportunities for those working in isolated services or with limited secondment opportunities. More importantly, online course material offers an alternative approach to delivering high-quality, engaging course content. The use of streaming media and a wide range of unified communication technologies (eg, video, instant messaging, and web-connected whiteboards and seminars) enhance faculty–student and student–student engagement.Citation2 Not only might this compliment more-traditional teaching methods, but this blended learning approach may be the preferred method of learning for the next ANP generation.Citation56 However, while there are clear benefits from flexible access and sharing experiences with others, there are risks. Multiple commitments and lack of group cohesiveness can significantly interfere with the effectiveness of these hybrid learning strategies.Citation57 Key recommendations for future implementation acknowledge participants’ preference for a blended approach, with face-to-face sessions providing “getting to know you” opportunities and enhancing commitment to the group learning process.

The LJMU MSc program demonstrates the full range of potential for hybrid learning strategies. It allows student ANPs from around the British Isles to participate. All lecture content is accessible live online, or in archived format. This also includes interactive seminars, case-based discussions, and presentations that review the evidence for clinical practice. If students are local or are within reasonable traveling distance, they are physically present at the session, with others joining online. Students are expected to participate “live” and use the archive for revision for occasional catch-up. The course design allows for regular meetings with all students present, to focus on clinical and practical skills, with simulation sessions playing an increasing role. These sessions are also designed to facilitate group cohesion (more frequent in the first months of the course, and again when the groups split into subspecialty modules). All out-of-area students have a local mentor who oversees clinical and practical training in the seconding unit. This allows differences in clinical practice between centers to be identified and discussed in the context of best evidence-based practice. The aim is for “real time” critical thinking to reinforce the importance of evidence-based practice, the need for continuous professional development, and the requirement for a continuous cycle of updated clinical guidelines and auditing. This learning process is designed to enhance the successful integration of research-based knowledge into clinical practice.

Conclusion

The advanced nurse practitioner role has expanded from delivering primary care to acute hospital subspecialties such as pediatric and neonatal intensive care. While there is increasing evidence of benefits for service delivery and patient care, devising a master’s program to fulfill these aspirations remains a challenge. No single program will meet the demands of the wide range of clinical expectations. Curriculum design needs to consider the complex interaction between faculty, clinical, professional, student, and educational factors. This review demonstrates how a thorough assessment of the available literature can be used to innovate and develop strategies to ensure an individual MSc program can be tailored to meet the needs of highly specialized advanced nursing practice.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GrayMRatcliffCMawyerRAbrief history of advanced practice nursing and its implications for WOC advanced nursing practiceJ Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs200027485410649144

- FitzgeraldCKantrowitz-GordonIHirschAAdvanced practice nursing education: challenges and strategiesNurs Res Pract2012201218

- American Academy of PediatricsAdvanced practice in neonatal nursingPediatrics20091231606160719482773

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing2008–2009 Enrollment and Graduations in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in NursingWashington, DCAmerican Association of Colleges of Nursing2009

- DelametterGLAdvanced practice nursing and the role of the pediatric critical care nurse practitionerCrit Care Nurs Q199921162110646428

- BrownAMBesunderJBachmanMDevelopment of a pediatric intensive care unit nurse practitioner programJ Nurs Admin200838355359

- DiCensoAThe neonatal nurse practitionerCurr Opin Pediatr1998101511559608892

- HallMSmithSLJacksonJENeonatal nurse practitioners: a view from perfidious Albion?Arch Dis Child1992674584621586193

- SmithSLHallMAdvanced neonatal nurse practitioners in the workforce: a review of the evidence to dateArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed201196F151F15521317125

- HewardYAdvanced practice in pediatric intensive care: a reviewPaediatr Nurs200921182119266777

- RobsonACopnellBJohnstonLOverseas experience of the neonatal nurse practitioner role: lessons for AustraliaContemp Nurse20021492316114190

- JacobsSAdvanced nursing practice in New Zealand: 1998Nurs Prax N Z19981341210481652

- JonesBNeonatal nurse practitioners: a model for expanding the boundaries of nursing culture in New ZealandNurse Prax N Z1999142835

- FryMLiterature review of the impact of nurse practitioners in critical care servicesNurs Crit Care201116586621299758

- NieminenALMannevaaraBFagerströmLAdvanced practice nurses’ scope of practice: a qualitative study of advanced clinical competenciesScand J Caring Sci20112566167021371072

- SorceLSimoneSMaddenMEducational preparation and postgraduate training curriculum for pediatric critical care nurse practitionersPediatr Crit Care Med20101120521219838142

- American Association of Colleges of NursingDNP Roadmap Task Force ReportWashington, DC USA2006

- CronenwettLDracupKGreyMThe Doctor of Nursing Practice: a national workforce perspectiveNurs Outlook20115991721256358

- CussonRMBuus-FrankMEFlanaganVAA survey of the current neonatal nurse practitioner workforceJ Perinatol20082883083618650829

- PresslerJLKennerCAThe NNP/DNP shortage: transforming neonatal nurse practitioners into DNPsJ Perinat Neonatal Nurs20092327227819704297

- FreedGLDunhamKMLarnarandKENeonatal nurse practitioners: distribution, roles and scope of practicePediatrics201012685686020956408

- SrivastavaNTuckerJSDraperESA literature review of principles, policies and practice in extended nursing roles relating to UK intensive care settingsJ Clin Nurs2008172671268018808636

- SmithSLHallMDeveloping a neonatal workforce: role evolution and retention of advanced neonatal nurse practitionersArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed200388F426F42912937050

- HallDWilkinsonARQuality of care by neonatal nurse practitioners: a review of the Ashington experimentArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed200590F195F20015846007

- LeslieAStevensonTNeonatal transfers by advanced nurse practitioners and paediatric registrarsArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed200388F509F51214602700

- Lloyd JonesMRole development and effective practice in specialist and advanced practice roles in acute hospital settings: systemic review and meta-synthesisJ Adv Nurs20054919120915641952

- WoodsLPThe contingent nature of advanced nursing practiceJ Adv Nurs19993012112810403988

- BennerPFrom Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing PracticeMenlo Park, CAAddison-Wesley1984

- CussonRMViggianoNMTransition to the neonatal nurse practitioner role: making the change from the side to the head of the bedNeonatal Netw200221212811923997

- BennerPInterpretive Phenomenology, Embodiment, Caring and Ethics in Health and IllnessNewbury Park, CASage1994

- LynehamJParkinsonCDenholmCExplicating Benner’s concept of expert practice: intuition in emergency nursingJ Adv Nurs20086438038718721157

- CussonRMStrangeSNNeonatal nurse practitioner transition: the process of reattaining expert statusJ Perinat Neonatal Nurs20082232933719011499

- LlewellynLEDayHLAdvanced nursing practice in paediatric critical carePaediatr Nurs200820303318335903

- RenshawMEHarveryMEHow clinicians in neonatal care see the introduction of neonatal nurse practitionersActa Paediatr20029118418711952007

- NicholsonPBurrJPowellJBe coming anadvanced practitioner inneonatal nursing: a psycho-social study of the relationship between educational preparation and role developmentJ Clin Nurs20051472773815946281

- GriffinMMelbyVDeveloping an advanced nurse practitioner service in emergency care: attitudes of nurses and doctorsJ Adv Nurs20065629230117042808

- CopnellBJohnstonLHarrisonDDoctor’s and nurses’ perceptions of interdisciplinary collaboration in the NICU and the impact of a neonatal nurse practitioner model of practiceJ Clin Nurs20041310511314687300

- WilsonLLBodinMBHoffmanJVincentJSupporting and retaining preceptors for NNP programs: results from a survey of NNP preceptors and program directorsJ Perinat Neonatal Nurs20092328429219704299

- BartonTDClinical mentoring of nurse practitioners: the doctors’ experienceBr J Nurs20061582082416936606

- LeeGAFitzgeraldLA clinical internship model for the nurse practitioner programmeNurs Educ Pract20088397404

- DunnLCreating a framework for clinical nursing practice to advance in the west Midlands regionJ Clin Nurs199872392439661386

- StrodtbeckFTrotterCLottJWCoping with transition: neonatal nurse practitioner education for the 21st centuryJ Pediatr Nurs1998132722789798362

- Bryant-LaikosiusDDiCensoAA framework for the introduction and evaluation of advanced practice nursing rolesJ Adv Nurs20044853054015533091

- FrankJEMullaneyDMDarnallRAStashwickCATeaching residents in the neonatal intensive care unit: a non-traditional approachJ Perinatol20002011111310785887

- FurlongESmithRAdvanced nursing practice: policy, education and role developmentJ Clin Nurs2005141059106616164523

- SpenceDAndersonMImplementing a prescribing practicum within a Master’s degree in advanced nursing practiceNurse Prax N Z2007232742

- PontinDJonesSChildren’s nurses and nurse prescribing: a case study identifying issues for developing training programmes in the UKJ Clin Nurs20071654054817335530

- BennerPStannardDHooperPLA “thinking-in-action” approach to teaching clinical judgment: a classroom innovation for acute care advanced practice nursesAdv Pract Nurs Q1996170779447047

- KingKAckermanMAn educational model for the acute care nurse practitionerCrit Care Nurs Clin North Am19957177766363

- ConwayJEvolution of the “expert” nurse: an example of the practical knowledge held by expert nursesJ Clin Nurs199812158167

- KessenichCTeaching health assessment in advanced nursing programmesNurs Educator200025170172

- LivesleyJWatersKTarbuckPThe management of advanced practitioner preparation: a work-based challengeJ Nurs Manag20091758459319575717

- ChikotasNEProblem based learning and clinical practice: the nurse practitioner’ perspectiveNurs Educ Pract20099393397

- DistlerJWCritical thinking and clinical competence: results of the implementation of student-centered teaching strategies in an advanced practice nurse curriculumNurse Educ Pract20077535917689424

- KenaszchukCMacMillanKvan SoerenMReevesSInterprofessional simulated learning: short-term associations between simulation and interprofessional collaborationBMC Med20119293821443779

- LancasterJWWongARobertsSJ‘Tech’versus ‘Talk’: A comparison study of two different lecture styles within a Master of Science nurse practitioner courseNurse Educ Today201232e14e822071277

- CurrieKBiggamJPalmerJCorcoranTParticipants’ engagement with and reactions to the use of on-line action learning sets to support advanced nursing role developmentNurse Educ Today20123226727221514016