Abstract

Introduction

The increasing demands for effective and efficient health care delivery systems worldwide have resulted in an expansion of the desired competencies that physicians need to possess upon graduation. Presently, medical residents require additional professional competencies that can prepare them to practice adequately in a continuously changing health care environment. Recent studies show that despite the importance of competency-based training, the development and evaluation of management competencies in residents during residency training is inadequate. The aim of this literature review was to find out which assessment methods are currently being used to evaluate trainees’ management competencies and which, if any, of these methods make use of valid and reliable instruments.

Methods

In September 2012, a thorough search of the literature was performed using the PubMed, Cochrane, Embase®, MEDLINE®, and ERIC databases. Additional searches included scanning the references of relevant articles and sifting through the “related topics” displayed by the databases.

Results

A total of 25 out of 178 articles were selected for final review. Four broad categories emerged after analysis that best reflected their content: 1) measurement tools used to evaluate the effect of implemented curricular interventions; 2) measurement tools based on recommendations from consensus surveys or conventions; 3) measurement tools for assessing general competencies, which included care-management; and 4) measurement tools focusing exclusively on care-management competencies.

Conclusion

Little information was found about (validated) assessment tools being used to measure care-management competence in practice. Our findings suggest that a combination of assessment tools should be used when evaluating residents’ care-management competencies.

Introduction

The professional training of health care providers is currently undergoing intensive reform, and this has in part, been linked to the rising demands for cost-effective and efficient health care delivery. Consumers of care are also demanding more accountability from their health care providers, resulting in an expansion of the desired professional competencies of physicians at the time of graduation, across and within the continuum of health care.Citation1–Citation3 In addition to the basic clinical knowledgeCitation4 and skills that residents need to acquire during their basic and specialty training, it is also expected that they are competent in other domains of medicine that would enable them to practice adequately in a continuously changing health care environment.Citation1,Citation5

In a wave of educational reform that has been characterized by the revision of the curricula of several national and individual postgraduate medical training programs, competency-based medical education has emerged as a preferred educational approach to address the changing societal needs. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the Accreditation Council For Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the United States,Citation6 and many more professional bodies in different countries have all formulated a broad range of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that physicians are required to master upon graduation. These knowledge, skills, and attitudes, collectively defined as “competencies”, have been bundled into various forms and packaged into different educational frameworks for training physicians.Citation6–Citation8 The Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS)Citation7 framework includes the roles as medical expert, scholar, health advocate, manager, collaborator, communicator, and professional, while the ACGME includes practice-based learning and improvement, patient care, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, medical knowledge, and systems-based practice.

So far, the outcomes of many of these initiatives have shown that graduating physicians feel inconsistently prepared in a lot of their expected physician roles, especially in the domains of manager and health advocate. Furthermore, while they consider the defined professional competencies to be at least moderately important,Citation9 several studies show that the attention given to the development of management competencies in many medical training programs is currently insufficient.Citation1 This is despite the perceived importance of competency-based training in the different professional domains.Citation3,Citation10–Citation12 While there is no single comprehensive definition of the manager role in health care, it is generally considered that physician managers are integral participants within health care organizations, are responsible for organizing sustainable practices, and also contribute to the effectiveness of the health care system.Citation6,Citation7 The role as manager as described by the CanMEDS framework includes key competencies that are aimed at raising residents’ awareness of the health care system and how to act responsibly within the system. Some of the areas these key competencies focus on include participation in activities that contribute to the effectiveness of the health care system, management of practice and career choices, the allocation of finite health care resources, and how to serve in administrative and leadership roles.Citation7 The ACGME competencies of system-based practice, on the other hand, demand responsibility within a larger context of the health care system, where residents are expected to be able to make effective use of health care resources in providing care that is of optimal value. Due to the similarities within these frameworks, however, and for the sake of clarity, we have chosen to coin the management competencies referred to in this article as “care-management”.Citation13

Context

In 2005, a new competency-based medial curriculum for all Dutch postgraduate medical programs was implemented in the Netherlands. The role as manager was one of the seven competencies of this new curriculum, which following implementation, turned out to be one that needed further clarification in terms of definition, interpretation, and evaluation in clinical practice. We carried out a number of studies to investigate an appropriate definition of this competency in practice as well as for the requirements needed to develop management competencies in residents during training.Citation14,Citation15

The findings from the different studies we conducted revealed that specific care-management training was necessary in both the undergraduate and postgraduate training of medical doctors in the Netherlands, and that formal training in this field was lacking. In separate studies investigating the perceived competence and educational needs in health care-management among medical residents, we also found that residents’ perceptions of care-management competencies in certain areas were inadequate.Citation15,Citation16 We therefore embarked on a project to design an educational intervention using the information we had gathered from previous research.Citation3,Citation12,Citation14,Citation15 However, for us to be able to measure the impact of our program or any changes that may occur in the residents as a result of our intervention, we realized that there was a need for valid and reliable assessment tools to measure the outcomes and also because providing constructive feedback (ie, both summative and formative) was an essential element of competency-based training.

There are a number of studies in the literature that have attempted to evaluate the impact of management training programs in many postgraduate medical institutions. The evaluations used in most of these studies, however, have been based upon trainee attendance, trainees’ evaluation of the programs, and in a few studies, pre- and post-test assessments of trainees’ knowledge of health care-management.Citation3 While many of the studies showed significant improvement in knowledge, the extent to which the trainees effectively applied the theory into practice after participation in these programs remains unknown. Furthermore, the question remains as to whether assessment tools are available that can objectively measure whether the desired competencies were achieved and, if so, how reliably they can be measured in the clinical work environment.Citation3,Citation12,Citation14,Citation15

It is obvious that the application of concrete assessment tools to vague conceptual constructs like “care-management” is a challenging task. This is because implicit within the concepts of reliability and validity rests the assumption of a stable, meaningful, quantifiable entity that can be measured, and that repeat measures applied to similar instances will produce similar results (reliability). In addition, it is expected that the reliable results will closely reflect an independent, broadly accepted “gold” or reference standard (validity). For this purpose, we chose to conduct a literature review to determine the content and attributes of reliable assessment tools, which could be used to evaluate medical residents’ care-management competencies. The main questions we set out to answer included:

which specific assessment methods are currently being used to evaluate medical residents’ care-management competencies;

which of these methods, if any, are valid and reliable; and

based on the evidence in the literature, what is the most reliable tool or assessment method for demonstrating physicians’ managerial “competency” in the clinical workplace?

Methods

Search strategy

In September 2012, a comprehensive search of the literature using the PubMed, Cochrane, Embase®, MEDLINE®, and ERIC databases was performed. We set out to identify all relevant literature that could inform us about effective and reliable assessment practices and tools currently being used or that could be used, to evaluate care-management competencies in medical residents. The keywords we initially used in our search strategy included “management”, “leadership”, and “education” which resulted in 9,058 hits. We therefore combined these broad terms in strings with more specific terms such as “care-management”, “assessment”, and “competency”, which resulted in 178 hits. The scope over which the searches were conducted included all available entries until November 2012, and these differed between databases – for example, MEDLINE (from 1946 to November 2012), Embase (from 1974 to November 2012), and PubMed (from 1953 to November 2012). Our search queries were saved and were rerun weekly from September through November 2012 to ensure that new publications were captured. New results were reviewed, and articles that met the eligibility criteria were included in the review. To be eligible for inclusion, each article had to focus on assessing management competency for medical students, residents, or fellows (for comprehensiveness of the continuum of training), published no earlier than 1950, and in no other language than English and Dutch. Criteria for exclusion were defined as articles which either did not have management skills or education as the major topic or did not contain (specific) outcome or information about care-management competency among the professional competencies that were evaluated in the studies. We performed additional searches to determine whether we had missed any relevant articles by scanning references of the eligible articles and sifting through “related topics” displayed by the databases.

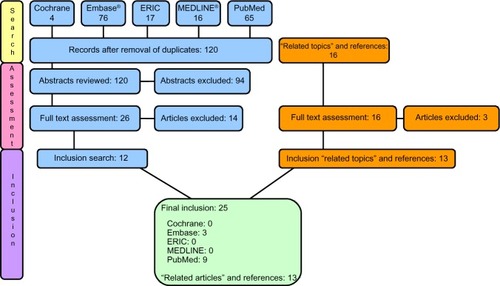

The 178 hits from our search in the PubMed, Embase, MEDLINE, ERIC, and Cochrane databases were reviewed, and after elimination of articles that were cited twice, we were left with a total of 120 articles. Two authors (LMG and LAS) independently determined the focus of each article by reviewing the abstract, and an article was selected for detailed examination if it satisfied the criteria for inclusion or if the authors could not exclude the article based on its abstract alone. A total of 26 potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full text after this round, and another 16 articles were found after scanning the related articles or references of the relevant articles. The resultant 42 articles were screened again in detail by each author, independently. In cases where there was no agreement on content, the two authors (LAS and LMG) tried to resolve this through consensus. Where a resolution could not be obtained, a third author (JOB) was consulted as arbiter. After this stage of the screening process, 25 articles were finally selected for the review process. For a comprehensive overview of the selection see .

Results

The 25 articles that were finally selected for the review showed, on further analysis, a certain degree of overlap in content, which resulted in four broad categories. These categories were labeled as follows: 1) assessment tools used to evaluate the effect of implemented curricular interventions; 2) assessment tools based on recommendations or views from consensus surveys or conventions; 3) assessment tools intended for assessing general competencies, which included care-management; and 4) assessment tools that focused exclusively on care-management competencies. and list our findings for each article category.

Table 1 Summary of categories 1 and 2

Table 2 Summary of categories 3 and 4

Category 1 – assessment tools used to evaluate the effect of implemented curricula interventions

In our review of articles used to measure residents’ care-management competencies, we found ten articles that measured trainees’ care-management competencies as a means of measuring the impact of the implemented curricula interventions.Citation17–Citation26 The tool that most of the reviewed articles (n=7) used was a self-designed pre- and post-test, most often designed by the course director, lecturers, or author. In some cases, the development of the test was not further clarified/specified.Citation19–Citation22,Citation25,Citation26 Most articles tested the residents on knowledge (N=4), comprehension (N=1), or perceived knowledge/comfort (N=1) regarding care-management related topics.Citation19,Citation21–Citation23,Citation25,Citation26 One study reported an improvement in knowledge but was unclear about the content of the multiple-choice questions (MCQs) in their self-designed pre- and post-test.Citation20 Two studies described assessments using a (modified) 360° evaluation tool (also known as multisource feedback [MSF]).Citation17,Citation18 Only one article described an evaluation by means of coding compliance and accuracy.Citation24 None of the articles reported any evidence in the literature or results about reliability or validity of the assessment tool. Furthermore, all of the articles, except one, contained small study groups or did not report the total amount of residents participating in the program.Citation17–Citation26

Category 2 – assessment tools based on recommendations or views from consensus surveys or conventions

In this section, only one article was found that described assessment tools based on the recommendation of a consensus report or expert opinions.Citation27 The article described the outcomes of a consensus conference in October 2001, organized by the University of Michigan and held near Detroit. The aim of the conference was to address the need for agreement and data on the best practices in assessment of the care-management competency. The article highlighted the best-practice assessment tool (based on relative strengths, weaknesses, and costs) for specific domains, with specific attention for care-management, based on consensus of nationally recognized experts in graduate medical education. Furthermore, it was concluded in the paper that a combination of assessment tools gave an accurate reflection of the resident’s competence and may allow for more divided gradations of competency. Residency programs were recommended to shape their own assessment systems to best address local needs and resources. In addition, the development and evaluation of more novel methods, including research in the field of computerized simulations of practice situations, was recommended.Citation27

Category 3 – assessment tools intended for assessing general competencies, which included care-management

We found 12 articles that described assessment tools used to measure care-management as part of the general evaluation of trainees’ ACGME or CanMEDS competencies.Citation28–Citation37 In the majority of these studies, new assessment tools were developed or previously known ones modified for this purpose.Citation29–Citation32,Citation34–Citation36,Citation38 Two articles evaluated self-developed oral simulated clinical examination (OSCE).Citation29,Citation32 The OSCEs in these studies had several stations, in order to assess residents’ competencies, including the care-management competency. While Jefferies et alCitation32 concluded in their study that “the OSCE could be useful as a reliable and valid method for simultaneously assessing multiple physician competencies”, Garstang et alCitation29 did not find any significant correlations between ABPMR (American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation) scores and OSCE scores on the manager role. We also found two articles that described the use of global rating forms to measure residents’ general competencies including care-management.Citation30,Citation35 Both studies modified and subsequently evaluated an existing global rating form. While Silber et alCitation30 argued that global rating forms may not be an appropriate instrument for distinguishing between the six ACGME general competencies, Reisdorff et alCitation35 focused on the psychometric aspects of global rating forms and noticed a significant increase in general competency scores for each year of training in every general competency category. None of these papers, however, satisfied our criteria for being valid and reliable assessment methods.

Two other articles developed an MSF evaluation tool to assess the six ACGME general competencies that included system-based practice as a measure of residents’ managerial and leadership competencies.Citation34,Citation37 Weigelt et alCitation34 concluded that “MSF (or 360° evaluation) forms provided limited additional information compared to the traditional faculty ratings” in their residents in the trauma or critical services training program. The second study showed a significant difference in general competency scores when assessed by different evaluators.Citation37 Other papers we examined revealed mere descriptions of assessment tools that were currently in use in various curricula, eg, MSF evaluation, OSCE, and portfolio,Citation31 as well as an inventory and perceived satisfaction of assessment tools that program directors were using in care-management training.Citation28 While a broad range of assessment tools were named, ie, MCQs, short-answer questions, essay, simulations, logbook, in-training evaluation report, oral examinations, and OSCE, the number of assessment tools used for evaluating the roles as collaborator and manager were remarkably less, compared with the other CanMEDS competencies. However, the majority of the program directors used in-training evaluation reports to assess care-management competencies, followed by MCQs and short-answer questions.

Two articles were themselves reviews of assessment tools used to assess general competencies of the ACGME curriculum. Both articles investigated the literature on the ACGME toolbox as well as different assessment tools.Citation33,Citation39 According to Swing,Citation39 OSCEs and standardized patient exams seemed to be the best methods for assessing high-stakes decisions. They recommended the complementary use of assessment methods that involved observation of interaction focused on specific aspects of residency performance (checklists and structured case-discussion orals).Citation39 Portfolios and 360° evaluation were reported as having the potential to provide unique insights into the performance of the resident, and should be further developed and tested.Citation39

In the other review, the authors concluded that it was seemingly impossible to measure the competencies independently of one another in any psychometrically meaningful way. However, they recommended not abandoning the general competencies but, instead to develop a specific and elaborate model to rationalize and prioritize various assessment instruments in light of the general competencies.Citation33,Citation40 Again, while both reviews identified assessment tools that were being used to evaluate general competencies, none of them identified the specific tools that could (singly or in combination) be used to reliably measure care-management competencies in physicians.

Category 4 – assessment tools for care-management competencies

In this category, only two articles were found that focused on assessment tools designed specifically for assessing care-management competency. One article was a literature review and discussed the use of portfolios, MCQs, OSCEs, and checklists in practice-management curricula.Citation41 The majority of the articles included in this review used one assessment tool for assessing the management competency. The authors noticed that checklists were the most common method of assessment within practice-management curricula, and the portfolio was the most common tool for assessing general competencies. A remarkable finding in the review was that only one study used long-term outcome measures.Citation40 The other article we found described a broad range of assessment tools: direct observation, global rating, 360° evaluation, portfolios, standardized oral exams, chart-stimulated recall oral examinations, OSCEs, and patient surveys.Citation42 It was concluded, based on consensus of conference proceedings, that a few primary assessment tools could be used for measuring the management competency of emergency medicine residents, namely, direct observation, global rating forms, 360° evaluations, portfolios, and knowledge testing: both oral and written.Citation42

Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine which assessment methods were currently being used to evaluate medical residents’ care-management competencies, to determine which of these methods, if any, were valid and reliable, and finally, based on the evidence in the literature, identify the most reliable tool or method of assessment for demonstrating physicians’ managerial competencies in the clinical workplace. The rationale for this review lay in the need for a method that could reliably assess residents’ management competencies within a competency-based educational framework. While assessment tools, either formative or summative, are expected to be competency specific, there is ongoing discussion about the feasibility of competency-specific training and assessment methods, and many educational programs are still being designed with the focus on specific competencies being set apart.

To begin with, our findings showed that many postgraduate education programs use global rating forms for evaluating general and specific competencies of their residents.Citation30,Citation33,Citation39,Citation40 This is remarkable considering that there is a lot of evidence that demonstrates that global rating forms have serious limitationsCitation30,Citation33,Citation39 and that they provide little or no information that can be used for constructive feedback to the trainees.Citation39 Nonetheless, it was still recommended that global rating forms should be considered in combination with other assessment tools for assessing physicians’ care-management competencies.Citation39,Citation42 Our findings also showed that 360° evaluations provided trainees with valuable information about their competencies in general,Citation18 although the instrument was not considered to be a useful tool to measure specific competencies independent of other instruments.Citation33,Citation34 Also, the reliability of this assessment tool was dependent on the instructions given to the raters, having the right number of evaluators, maintaining confidentiality, and how well-defined the competence-domains were.Citation34 While the face validity of this tool is high by design (due to multiple perspectives represented and the number of evaluators involved), there is little data published about its content validity.Citation18,Citation42 We also discovered that OSCEs were widely used tools in assessing both the skills and knowledge of residents, as well as their roles as medical experts and communicators.Citation32 However, Frohna et alCitation27 felt that this assessment tool needed further evaluation, especially in the domain of care-management.

Although portfolios have been found to provide residents with a good view of the gaps in their knowledge and promote independent learning,Citation42 we discovered that they were considered time consuming as assessment tools for measuring care-management competencies. This was because of the diversity of content they contain and the lack of a validated instrument to “grade” portfolios.Citation31,Citation39 Nonetheless, they were considered to be useful for the assessment of certain dimensions of the competency as manager that otherwise would be difficult to assess using other methods, eg, systems-based practice.Citation39

Many of the articles we found showed that there is no single assessment tool that can provide sufficient information about the development or current level of competence in trainees and that a combination of tools would be necessary to measure residents’ level of care-management competence in a valid way. Our findings fall in line with the report by van der Vleuten and SchuwirthCitation41 who proposed that the combination of qualitative and quantitative assessments in evaluating professional behavior during training was apparently superior for assessing clinical competence. They argued that it was impossible to have a single method of assessment capable of covering all aspects of competencies of the layers of Miller’s pyramid. Hence, a blend of methods were needed, some of which will be different in nature and which could mean less numerical with less standardized test-taking conditions. According to the authors, there were no inherently inferior assessment methods for measuring professional competency and that the reliability of any assessment (tool) depended on sampling as well as on how they were applied in clinical practice. The authors pleaded for a shift of focus regarding assessment, away from individual assessment methods for separate parts of competencies towards assessment as a component that is inextricably woven together with the other aspects of a training program. This way, assessment would change from a psychometric problem to be solved by a single assessment method to an educational design problem that encompasses the entire curriculum.Citation41 It is our firm belief that such a combination of assessment methods would be applicable in the area of care-management competency assessment, despite the fact that findings from our review did not support a particular combination of assessment tools.

In many of the articles we reviewed, we found that it was difficult to unambiguously discriminate between what was being measured in terms of care-management “competency” and management “competence”. While competence as a generic term describes an individual’s overall ability to perform a specific task and refers to the knowledge and skills the individual needs to perform the particular task,Citation43 competency, on the other hand refers to specific capabilities, such as leadership, collaboration, communication, and management capabilities demonstrated while performing a task. Competence is considered a habit of lifelong learning rather than an achievement, reflecting the relationship between a person’s abilities and the task to be performed.Citation44–Citation46 Competency, however, involves the collective application of a person’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes and is aimed at standardizing how knowledge, skills, and abilities are combined in describing what aspects of performance are (considered) important in particular areas. A trainee’s clinical reasoning may therefore appear to be competent in areas in which their knowledge base is well organized and accessible but may appear to be much less competent in unfamiliar contexts.Citation4,Citation47 The objective of the ideal assessment tool is therefore to improve trainees’ overall performance by providing insights into actual performance, stimulating the capacity to adapt to change and possessing the capacity to find and generate new knowledge.Citation47,Citation48

There are a few limitations in this study that are worth mentioning. We might have missed some relevant and helpful articles on the subject by restricting the scope of the search to English- and Dutch-language articles. As we only reported literature published in educational and biomedical journals, it is possible that effective assessment initiatives in residency programs were left out of our search and the review. It is also possible that we omitted a number of ongoing studies that fell out of the specified search period of our study. We believe, nonetheless, that our extensive and systematic methodological approach would have limited the chances of missing critical information.

Although we could not identify a single valid, feasible, and/or reliable care-management assessment tool from the literature review, we discovered various tools that were being combined in different ways to assess the care-management competencies of residents in clinical practice. Our findings suggest that the use of a single assessment tool is insufficient for measuring the care-management competencies of residents and that a combination of qualitative and quantitative tools would be highly preferable.Citation41 Also, educators and trainers need, in the absence of a single assessment tool, to combine different assessment tools during training to obtain a better perspective of the resident’s care-management competency level. We believe that a combination of 360° evaluation, portfolio, and assessment of individual projects would be an interesting combination of assessment tools to use in daily practice. For example, 360° evaluation could be useful for evaluating care-management competencies during tasks such as chairing a meeting or the management of a ward. Portfolios would add self-evaluation and perhaps a summary of care-management tasks and interest, while conducting individual projects would provide residents with opportunities to develop their care-management competencies and leadership abilities.

Finally, in addition to determining the validity and reliability of existent assessment tools in health care-management and how they can effectively be used to monitor and improve physician care-management competencies, our recommendation for additional research would include investigating which combinations of assessment tools would yield reliable assessments of care-management in clinical practice. Interesting areas worth further investigation include subdomains of care-management, eg, levels of management competency that should be made mandatory and those which should be optional for physicians to master. It would also be interesting to perform further research on how physicians, educators, and medical managers personally perceive how care-management competencies should be evaluated and also explore the specific essential management skills and knowledge that should be evaluated.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BohmerRMJKnoopCIThe challenge facing the US healthcare delivery systemHarvard Business School Background Note 606-09662006 (Revised Jun 2007)

- PorterMEThijsburgEORedefining Health Care: Creating Value Based Competition on ResultsBostonHarvard Business Press20067195

- BusariJOBerkenboschLBrounsJWPhysicians as managers of health care delivery and the implications for postgraduate medical training: a literature reviewTeach Learn Med201123218619621516608

- BordageGZacksRThe structure of medical knowledge in the memories of medical students and general practitioners: categories and prototypesMed Educ19841864064166503748

- StephensonJDoctors in managementBMJ20093394595

- Accreditation Council for General Medical EducationACGME Outcome project 1999 http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/medschool/otlm/ratl/references_pdf/Module_4/ACGMEOutcomeProject.pdfAccessed January 21, 2014

- Royal college of Physicians and surgeons of Canada, CanMEDS 2005Canada Available from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/framework/the_7_canmeds_roles_e.pdfAccessed January 21, 2014

- van ReenenRden RooyenCSchelfhout-van DeventerVModernisering medische vervolgopleidingen: nieuw kaderbesluit CCMS [Framework for the Dutch Specialist Training Program]. Kaderbesluit centraal college medische specialismenUtrecht, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij tot bevordering der Geneeskunst Available from: http://knmg.artsennet.nl/Opleiding-en-herregistratie/Algemene-informatie/Nieuws/O-R-Nieuwsartikel/Modernisering-medische-vervolgopleidingen-nieuw-kaderbesluit-CCMS.htmAccessed January 14, 2014 Dutch

- StutskyBJSingerMRenaudRDetermining the weighting and relative importance of CanMEDS roles and competenciesBMC Res Notes2012535422800295

- DaugirdAJSpencerDCThe perceived need for physician management trainingJ Fam Pract19903033483513422307950

- PatelMSLypsonMLDavisMMMedical student perceptions of education in health care systemsAcad Med20098491301130619707077

- BaxMFPBerkenboschLBusariJOHow do medical specialists perceive their competency as physician-managers?Int J Med Educ20112133139

- ThorsenLCompetency Definitions and Recommended Practice Performance Tools2007 Available from: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/430_CompetencyDefinitions_RO_ED_10182007.pdfAccessed December 26, 2013

- BerkenboschLBrounsJWHeyligersIBusariJOHow Dutch medical residents perceive their competency as manager in the revised postgraduate medical curriculumPostgrad Med J201187103268068721693572

- BrounsJWBerkenboschLPloemen-SuijkerFDHeyligersIBusariJOMedical residents perceptions of the need for management education in the postgraduate curriculum: a preliminary studyInt J Med Educ201017682

- SchoenmakerSGBerkenboschLAhernSBusariJOVictorian junior doctors’ perception of their competency and training needs in healthcare managementAust Health Rev201337441241723962412

- KocharMSSimpsonDEBrownDGraduate medical education at the Medical College of Wisconsin: new initiatives to respond to the changing residency training environmentWMJ20031022384212754907

- HigginsRSBridgesJBurkeJMO’DonnellMACohenNMWilkesSBImplementing the ACGME general competencies in a cardiothoracic surgery residency program using 360-degree feedbackAnn Thorac Surg2004771121714726026

- BabitchLATeaching practice management skills to pediatric residentsClin Pediatr (Phila)200645984684917041173

- BabitchLAChinskyDJLeadership education for physicians. Refine your focus and communicate your goals when developing physician leadership programsHealthc Exec2005201495115656230

- BayardMPeeplesCRHoltJDavidDJAn interactive approach to teaching practice management to family practice residentsFam Med200335962262414523656

- EssexBJacksonRNMoneymed: a game to develop management skills in general practiceJ R Coll Gen Pract1981312337357397338867

- HemmerPRKaronBSHernandezJSCuthbertCFidlerMETazelaarHDLeadership and management training for residents and fellows: a curriculum for future medical directorsArch Pathol Lab Med2007131461061417425393

- JonesKLebronRAMangramADunnEPractice management education during surgical residencyAm J Surg20081966878881 discussion 881–87219095103

- JunkerJAMillerTDavisMSPractice management: a third-year clerkship experienceFam Med2002342878911874029

- LoPrestiLGinnPTreatRUsing a simulated practice to improve practice management learningFam Med200941964064519816827

- FrohnaJGKaletAKachurEAssessing residents’ competency in care management: report of a consensus conferenceTeach Learn Med2004161778414987180

- ChouSColeGMcLaughlinKLockyerJCanMEDS evaluation in Canadian postgraduate training programmes: tools used and programme director satisfactionMed Educ200842987988618715485

- GarstangSAltschulerELJainSDelisaJADesigning the objective structured clinical examination to cover all major areas of physical medicine and rehabilitation over 3 yrsAm J Phys Med Rehabil201291651952722469878

- SilberCGNascaTJPaskinDLEigerGRobesonMVeloskiJJDo global rating forms enable program directors to assess the ACGME competencies?Acad Med200479654955615165974

- LeeAGOettingTBeaverHACarterKThe ACGME Outcome Project in ophthalmology: practical recommendations for overcoming the barriers to local implementation of the national mandateSurv Ophthalmol200954450751719539838

- JefferiesASimmonsBTabakDUsing an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to assess multiple physician competencies in postgraduate trainingMed Teach2007292–318319117701631

- LurieSJMooneyCJLynessJMMeasurement of the general competencies of the accreditation council for graduate medical education: a systematic reviewAcad Med200984330130919240434

- WeigeltJABraselKJBraggDSimpsonDThe 360-degree evaluation: increased work with little return?Curr Surg2004616616626 discussion 627–61815590037

- ReisdorffEJCarlsonDJReevesMWalkerGHayesOWReynoldsBQuantitative validation of a general competency composite assessment evaluationAcad Emerg Med200411888188415289197

- VarneyAToddCHingleSClarkMDescription of a developmental criterion-referenced assessment for promoting competence in internal medicine residentsJ Grad Med Educ200911738121975710

- RoarkRMSchaeferSDYuGPBranovanDIPetersonSJLeeWNAssessing and documenting general competencies in otolaryngology resident training programsLaryngoscope2006116568269516652072

- ReisdorffEJHayesOWCarlsonDJWalkerGLAssessing the new general competencies for resident education: a model from an emergency medicine programAcad Med200176775375711448836

- SwingSRAssessing the ACGME general competencies: general considerations and assessment methodsAcad Emerg Med20029111278128812414482

- KolvaDEBarzeeKAMorleyCPPractice management residency curricula: a systematic literature reviewFam Med200941641141919492188

- van der VleutenCPSchuwirthLWAssessing professional competence: from methods to programmesMed Educ200539330931715733167

- DynePLStraussRWRinnertSSystems-based practice: the sixth core competencyAcad Emerg Med20029111270127712414481

- ClintonMMurrellsTRobinsonSAssessing competency in nursing: a comparison of nurses prepared through degree and diploma programmesJ Clin Nurs2005141829415656852

- LeachDCCompetence is a habitJAMA2002228724324411779269

- KlassDReevaluation of clinical competencyAm J Phys Med Rehabil200079548148610994893

- LeachDCBuilding and assessing competence: the potential for evidence-based graduate medical educationQual Manag Health Care2002111394412455341

- BusariJOArnoldAEducating doctors in the clinical workplace: unraveling the process of teaching and learning in the medical resident as teacherJ Postgrad Med200955427828320083878

- CoxMPacalaJTVercellottiGMSheaJAHealth care economics, financing, organization, and deliveryFam Med2004Suppl 36S20S3014961399