Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate early variations in lymphatic circulation of the arm pre- and post-sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and conservative breast surgery by lymphoscintigraphy (LS).

Patients and methods

Between 2005 and 2012, 15 patients underwent LS before and after the SLNB (total=30 studies). The pre-SLNB study was considered the control. Early images within twenty minutes (dynamic and static images) and delayed images within ninety minutes of arms and armpits were acquired using a gamma camera. The LS images before and after the SLNB of each patient were paired and compared to each other, evaluating the site of lymphatic flow (in the early phase) and identifying the number of lymph nodes (in the late phase). These dynamic images were subjected to additional quantitative analysis to assess the lymphatic flow rate using the slope assessed by the angular coefficient of the radioactivity × time curves in areas of interest recorded in the axillary region. The variations of lymphatic flow and the number of lymph nodes in the post-SLNB LS compared to the pre-SLNB LS of each patient were classified as decreased, sustained or increased. The clinical variables analyzed included the period between performing the SLNB and the subsequent LS imaging, age, body mass index, number of removed lymph nodes, type of surgery and whether immediate oncoplastic surgery was performed.

Results

The mean age was 54.53±9.03 years (36–73 years), the mean BMI was 27.16±4.16 kg/m2 (19.3–34.42), and the mean number of lymph nodes removed from each patient was 1.6±0.74 (1–3). There was significant difference in the time between surgery and the realization of LS (p=0.002; Mann–Whitney U test), but in an inverse relationship, the higher was the range, the smaller was the lymphatic flow, indicating a gradual reduction of lymphatic flow after surgery (Spearman’s p=0.498, with p=0.013).

Conclusion

Upper limb lymphatic flow gradually decreased after the SLNB and conservative breast surgery in this study, but these results are exploratory because of the small sample size. Further studies are needed to confirm and to investigate more in depth these findings.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common causes of death in women, with increasing incidence in developed and developing countries.Citation1 It requires more aggressive and costly treatments in advanced stages,Citation2,Citation3 which can cause more immediate or delayed posttreatment complications, including bleeding, infection, seroma, axillary web syndrome, chronic pain, paresthesia due to intercostal brachial nerve injury, decreased range of motion and muscle weakness in the shoulder and, especially, lymphedema.Citation4,Citation5 The latter is the largest and most important morbidity,Citation6,Citation7 with increased incidence when associated with complementary radiation therapy.Citation8–Citation10

Lymphedema is difficult to diagnose, especially in the early stages.Citation9,Citation11 It is incurable when established. Studies show that surgery and drug therapies are unsuccessful,Citation12,Citation13 although lymphedema may be avoided, treated and controlled by daily preventive measures.Citation14,Citation15 Improper diagnosis always causes delayed therapy and at a more advanced stage of morbidity. Early treatment leads to fast improvement and prevents lymphedema progression.Citation9,Citation16

Lymphedema prevention has been attempted using more conservative intraoperative methods of approach to the axillary chain, including the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). The authors have introduced innovative methods in recent decades, accounting for a new standard of care for early-stage patients.Citation17,Citation18 These improvements enable selective, safer and less mutilating resections with satisfactory results and a substantial reduction of surgical morbidity,Citation19,Citation20 albeit restricted to patients with clinically negative axilla.Citation21,Citation22

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) is the first node receiving lymphatic drainage from the primary tumor.Citation23,Citation24 Increasing focus on morbidity triggered by axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) and toward increasing the capacity of detection of small tumor cells in the SLN have increased the indication of SLNBCitation25 because this method is safe and less invasive, with reduced treatment costs.Citation26,Citation27

The primary goals of SLNB were to generate information on the stage of the axillary chain and to avoid unnecessary axillary dissection, decreasing upper limb morbidities. These morbidities are lesser in SLNB than in ALND,Citation28–Citation30 improving the patient’s quality of life.Citation31 Although the application of SLNB has increased, its use reduces but does not eliminate the risk of developing lymphedema,Citation32,Citation33 with the incidence ranging from 0% to 15.8%.Citation34–Citation36 The transection of arm lymph vessels during SLNBCitation37,Citation38 and obesityCitation38,Citation39 may trigger lymphedema. Britton et alCitation40 also found a small number of patients with a coincidental SLN draining the breast and upper limb, the removal of which causes the disruption of lymphatic drainage of the upper limb, consequently increasing the risk of developing lymphedema. Several authors are using axillary reverse mapping to avoid injuring coincidental lymph vessels.Citation41–Citation44

Lymphoscintigraphy (LS) is an available, inexpensive, easily performed, low-morbidity complementary imaging method. It is based on the principle that radiocolloids and radiolabeled macromolecules of appropriate size and properties injected in the interstitial tissue reach afferent lymph vessels and are transported to lymph nodes, mapping the lymphatic system. Colloids labeled with 99mTc are the most used radiotracers and can effectively assess the lymph systems of the upper and lower limbs, although most publications focus their lymphatic studies on the lower limbs.Citation33,Citation45 The introduction of nuclear medicine concept in mastology for SLN identification is widespread. The use of vital dyes or radiopharmaceuticals alone or in combination is very effective for the accurate identification of lymph nodes.Citation46–Citation48

LS of the upper limbs after mastectomy was used to evaluate treatment efficacy after physical therapy of the arm with lymphedema already established. Recently, we conducted a study to assess lymph flow in the upper limbs with and without physical therapy stimulation in recently mastectomized patients submitted to ALND and without lymphedema. LS effectively illustrated the improvements in poststimulation lymph flow, directing early physical therapy behaviors in the group of patients at potential risk of developing late lymphedema.Citation49 We have found no evidence for evaluation of the lymphatic circulation following immediate conservative breast surgery with SLNB in the literature.

The objective of this study was to evaluate early variations in lymphatic circulation of the arm pre- and post-SLNB and conservative breast surgery by LS.

Patients and methods

This longitudinal observational study included 26 patients aged >18 years with unilateral breast cancer who were submitted to SLNB between 2005 and 2012. A total of 11 patients were excluded, including four submitted to ALND during surgery, given the identification of lymph node metastases in the biopsies, two with no good quality of LS images and five who withdrew their consent during the study. The final sample consisted of 15 patients who underwent LS before and after the SLNB for a total of 30 studies; the pre-SLNB study was considered the control. None of the patients submitted to previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy with knowledge of lymphatic pathology prior to SLNB and with the presence of inflammatory or infectious processes associated with the upper limbs were included. The patients were informed about the study and freely signed the informed consent form; the study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Barretos Cancer Hospital, Brazil.

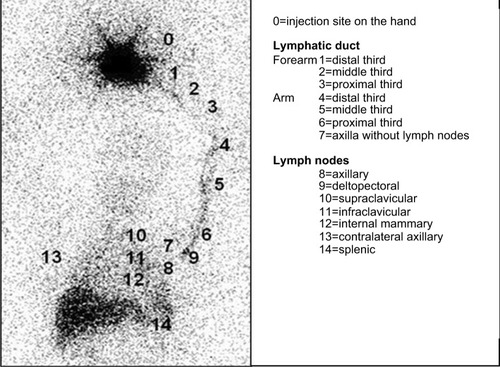

LS images were acquired and processed according to the protocol proposed by Sarri et alCitation49 using a two-headed, low-energy collimator and high-resolution nuclear gamma camera (GE Medical Systems Israel Ltd, Millennium VG Hawkeye, Tirat Hacarmel, Israel), with acquisition of early images of the arms and armpits (dynamic phase [DYNAMIC] – one frame/minute for 20 minutes); the static immediate phase (STATIC, images of the arms and axillary regions for 10 minutes each) started immediately after the dynamic phase, and the delayed-phase whole-body scan (WBS) images were acquired 90 minutes after the injection of 0.5 mL of 37 MBq (99m)Tc-phytate (Nuclear and Energetic Research Institute – IPEN, FITA-TEC fitato de sódio [99m Tc], São Paulo, Brazil), which was administered subcutaneously (fan technique) into the second interdigital space.Citation49 The LS images before and after the SLNB of each patient were paired and compared to each other, evaluating the site of lymphatic flow (in the early phase) and identifying the number of lymph nodes (in the late phase). The sequential ordinal classification from the injection site in the hand to the farthest site reached, which ranged from 0 to 14, as proposed by Sarri et alCitation49 and as shown in , was used to locate the site of the afferent lymphatic inflow junction in the upper limb. The dynamic images were subjected to additional quantitative analysis to assess the lymphatic flow rate using the slope assessed by the angular coefficient of the activity × time curves in areas of interest recorded in the axillary region.Citation49 The variations of lymphatic flow and the number of lymph nodes in the post-SLNB LS compared to the pre-SLNB LS of each patient were classified as decreased, sustained or increased.

Figure 1 Lymphoscintigraphy including the area from the hand to the abdominal region.

Results

The mean age of the analyzed sample (n=15) was 54.53±9.03 years (36–73 years), the mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.16±4.16 kg/m2 (minimum – maximum: 19.3–34.42), and the mean number of lymph nodes removed from each patient was 1.6±0.74 (minimum – maximum: 1–3).

The tumors were predominantly in the left breast (n=11; 73.4%) compared to the right breast (n=4; 26.0%). Quadrantectomy was the procedure of choice (n=13; 86.0%), followed by simple mastectomy (n=2; 14.0%). An immediate oncoplastic surgery was performed in three patients.

Comparisons between the site of the afferent lymphatic inflow junction and the total number of lymph nodes identified and the subsequent classifications into decreased, sustained or increased for each group of images were made after pairing the dynamic, static and WBS images from the pre- and post-SLNB studies of each patient. Only two subgroups were formed for statistical analysis purposes: patients with decreased (decreased group, DG) versus patients with sustained/increased (sustained/increased group, SIG) lymphatic flow and number of lymph nodes post-SLNB. The clinical variables analyzed included the period between performing the SLNB and the subsequent LS imaging, age, BMI, number of removed lymph nodes, type of surgery and whether immediate oncoplastic surgery was performed.

Dynamic image analysis identified eight patients with decreased (DG=8) and seven with sustained/increased lymphatic flow rates (SIG=7). No statistically significant differences were observed between the variables, as shown in . Both patients submitted to simple mastectomy showed a decreased lymphatic flow rate, seven of the 13 patients submitted to quadrantectomy showed an increased lymphatic flow rate and six showed a decreased rate without significant lymphatic variation associated with the surgical approach (p=0.467, Fisher’s exact test). The lymphatic flow rate increased after the SLNB in the three patients submitted to immediate oncoplastic surgery, which proved to be a key factor (p=0.07, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 1 Lymphatic flow velocity (angular coefficient). Paired variables analysis of lymphatic flow rate in early dynamic images in the decreased (DG) versus sustained/increased (SIG) subgroups

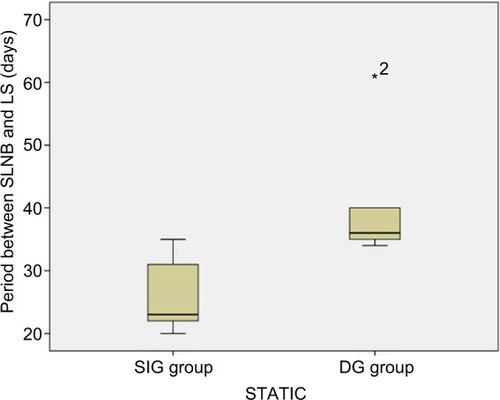

Analysis of the static image (STATIC) revealed a significant difference between DG (n=6) and SIG (n=9) with regard to the variable site of the afferent lymphatic inflow junction and the time period between the SLNB and the post-SLNB LS scan (p=0.002, Mann–Whitney U test), albeit in an inverse relationship: the longer the period is, the smaller the site of the afferent lymphatic inflow junction will be, indicating a gradual decrease of lymphatic flow post-SLNB (ρ =−0.498, with p=0.013; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient – Spearman’s ρ). No statistically significant differences were noted in that image regarding the other variables analyzed, as shown in . The representative figure depicts the data in a box plot ().

Figure 2 Box plot of the time elapsed between the SLNB and the post-SLNB scintigraphy scans regarding the subgroups sustained/increased versus decreased sites of afferent lymphatic inflow junctions, according to Static Image (STATIC).

Abbreviations: SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; SIG, sustained/increased group; DG, decreased group; LS, lymphoscintigraphy.

Table 2 Site of the afferent lymphatic inflow junction in Static Images (STATIC). Paired variables analysis in the decreased (DG) versus sustained/increased (SIG) subgroups

When analyzing the clinical variables, no statistically significant differences were observed between the subgroups formed using the criterion decreased (DG) versus sustained/increased (SIG) variation of the total number of lymph nodes identified in each study phase. One to three axillary lymph nodes were identified, although the uptake intensity changed in WBS images.

Discussion

An SLNB in patients submitted to early-stage breast cancer treatment is a strategy to minimize the risk of morbidities associated with therapy, primarily upper limb lymphedema.Citation3,Citation4,Citation50 Currently, the decrease in practice of ALND after positive SLN for micrometastases or an isolated tumor suggests that ALND is more prognostic than therapeutic.Citation51–Citation53 Although SLNB reduces the risk of developing lymphedema, other factors, including disruption of arm lymphatic vesselsCitation37,Citation38 and obesity,Citation38,Citation39 may lead to the onset of this condition, especially when associated with adjuvant radiation therapy.Citation8,Citation9 McLaughlin et alCitation54 verified that 50% of patients submitted to SLNB were concerned with the development of lymphedema, in contrast to 75% of those submitted to ALND in their study. This concern is understandable in this group of patients, although it is unfounded in the SLNB group, given the low risk of developing lymphedema. Our study showed no early change in lymphatic flow related to BMI.

Nuclear medicine technology has a key role in the evaluation of the lymphatic system.Citation55 Considering the system’s complexity, X-ray images remain a challenge because the lymphatic system is not an organ; instead, it connects different structures from small lymphatic capillaries to main ducts through lymph nodes and valves. Thus, each of those structures may be visualized in separate images from each other. The lymphatic system may also be involved in various diseases, including cancer and infectious diseases.Citation33,Citation56 This study chose to analyze lymphatic circulation by LS for recording physiological changes at different time periods following radiopharmaceutical injection to map lymph flow until reaching lymph nodes with immediate and delayed images. The visualizations of both the total number of evidenced lymph nodes and more axillary lymph nodes were also more representative in the most delayed images, corroborating the study by Sarri et al;Citation49 the authors showed that the acquisition time determined the site of the afferent radiopharmaceutical inflow junction, identifying more lymph nodes in delayed images in patients with breast cancer submitted to surgery and axillary lymphatic approach. The inclusion of the quantitative analysis of the lymphatic flow rate using the angular coefficient (slope) aimed to identify small and still unnoticeable changes in the images and also to minimize errors of subjective interpretations in the qualitative analysis. Celebioglu et alCitation57 used LS with qualitative and quantitative analyses to monitor patients submitted to SLNB. The second examination was performed 2–3 years after surgical treatment and radiation therapy, comparing the operated with non-operated arms, and no differences were detected between the limbs. We have found no other similar studies in the literature, with the exception of the study described above, conducted by Sarri et al.Citation49 The three patients in our study who were submitted to immediate oncoplastic surgery exhibited an increased lymphatic flow rate in the early postoperative period. The compensation of lymphatic flow into the inflammatory area should be considered.Citation58 The lymphatic system serves a key immunological function during the inflammatory process, promoting the influx of immune cells and specific antigens and draining into the lymph nodes with an increased drainage volume.Citation59,Citation60 We have found no studies for comparison that are similar to ours that assess the lymphatic circulation in the immediate pre- and postsurgical period of patients submitted to SLNB. Patients submitted to prophylactic mastectomy on whom SLNB was performed showed no significant increase in the risk of developing lymphedema.Citation61 Further studies using early and delayed postsurgery LS imaging should be conducted to identify the actual damage from SLNB to the lymphatic flow, especially when combined with more extensive breast surgery, including oncoplastic surgery.

This study showed no variation in the total number of lymph nodes identified pre- and post-SLNB. Probably, it can be explained by the small number of patients with a coincidental SLN draining the breast and upper limb, as described by Britton et al,Citation40 and that will not have an impact on the development of late lymphedema. Perhaps, the association of many studies, including axillary reverse mapping too, can avoid injuring coincidental lymph vesselsCitation41–Citation44 and identify patients who may benefit from early physiotherapeutic stimulationCitation49 after SLNB.

We have observed that the period between the SLNB and the LS was crucial to identify any variations in lymphatic flow, and that the period had an inverse relationship with flow: the longer the period between the SLNB and the monitoring of LS imaging is, the lower the lymphatic flow will be. These findings are exploratory. We studied only one patient following SLNB later. The lymphatic flow was evaluated at three different time periods by LS. The first scintigraphy was performed 15 days before the surgical procedure. The second examination was performed 22 days after surgery and the third one 6 months later. The immediate postoperative scintigraphy showed that the intensity of radiopharmaceutical uptake increased in the axillary lymph node, but the late postoperative study (6 months) showed a relatively lower uptake in this lymph node compared to the two previous studies. Maybe, these findings can be related to the acute inflammatory process after local manipulation and damage to the lymphatic chain in early postoperative evaluation and fibrosis in later evaluation. Further studies, focusing on different time periods between the SLNB and the LS combined with limb measurement, should be conducted to identify the actual impact of such a finding on conservative surgery. It would be important to assess which is the right timing to perform the lymphoscintigraphic study of the upper limb after conservative breast surgery and SLNB, in order to have the greater prognostic value in patients with an increased risk of lymphedema, such as obesity and radiotherapy.

Conclusion

Upper limb lymphatic flow gradually decreased after an SLNB in this study, but these results are exploratory because of the small sample size. Further studies are needed to confirm and to investigate more in depth these findings.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

AJ Sarri is the father of VC Sarri. SM Moriguchi is the mother of PHM Cação, and they are both physicians in diagnostic imaging.

References

- De SantisCEBrayFFerlayJLortet-TieulentJAndersonBOJemalAInternational variation in female breast cancer incidence and mortality ratesCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev201524101495150626359465

- AntonEBotnariucNAncutaEDorofteiBCiobicaAAntonCThe importance of clinical and instrumental diagnostic in the mammary gland cancerRev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi2015119241041826204645

- KootstraJJDijkstraPURietmanHA longitudinal study of shoulder and arm morbidity in breast cancer survivors 7 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissectionBreast Cancer Res Treat2013139112513423588950

- AertsPDDe VriesJVan der SteegAFRoukemaJAThe relationship between morbidity after axillary surgery and long-term quality of life in breast cancer patients: the role of anxietyEur J Surg Oncol201137434434921296542

- ChoYDoJJungSKwonOJeonJYEffects of a physical therapy program combined with manual lymphatic drainage on shoulder function, quality of life, lymphedema incidence, and pain in breast cancer patients with axillary web syndrome following axillary dissectionSupport Care Cancer20162452047205726542271

- Lopez PenhaTRvan RoozendaalLMSmidtMLThe changing role of axillary treatment in breast cancer: who will remain at risk for developing arm morbidity in the future?Breast201524554354726051795

- ShahCArthurDWWazerDKhanARidnerSViciniFThe impact of early detection and intervention of breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic reviewCancer Med2016561154116226993371

- EzzoJManheimerEMcNeelyMLManual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema following breast cancer treatmentCochrane Database Syst Rev20155CD00347525994425

- LahtinenTSeppäläJVirenTJohanssonKExperimental and analytical comparisons of tissue dielectric constant (TDC) and bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) in assessment of early arm lymphedema in breast cancer patients after axillary surgery and radiotherapyLymphat Res Biol201513317618526305554

- VieiraRAda CostaAMde SouzaJLRisk factors for arm lymphedema in a cohort of breast cancer patients followed up for 10 yearsBreast Care (Basel)2016111455027051396

- AkitaSMitsukawaNRikihisaNEarly diagnosis and risk factors for lymphedema following lymph node dissection for gynecologic cancerPlast Reconstr Surg2013131228329023357989

- BulleyCGaalSCouttsFComparison of breast cancer-related lymphedema (upper limb swelling) prevalence estimated using objective and subjective criteria and relationship with quality of lifeBiomed Res Int2013201380756923853774

- KorpanMIChekmanISStarostyshynRVFialka-MozerVНаціональна наукова медична бібліотека України [Lymphedema: clinic-therapeutic aspect]Lik Sprava20103–41120 Ukrainian [with English abstract]

- StuiverMMten TusscherMRAgasi-IdenburgCSLucasCAaronsonNKBossuytPMConservative interventions for preventing clinically detectable upper-limb lymphoedema in patients who are at risk of developing lymphoedema after breast cancer therapyCochrane Database Syst Rev20152CD00976525677413

- WenczlEDaganatos betegekben kialakult másodlagos nyiroködéma ellátása [Management of secondary lymphedema in patients with cancer]Orv Hetil201615713488494 Hungarian [with English abstract]26996895

- RidnerSHDietrichMSKiddNBreast cancer treatment-related lymphedema self-care: education, practices, symptoms, and quality of lifeSupport Care Cancer201119563163720393753

- KragDNWeaverDLAlexJCFairbankJTSurgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probeSurg Oncol199326335339 discussion 3408130940

- GiulianoAEKirganDMGuentherJMMortonDLLymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancerAnn Surg19942203391398 discussion 398–4018092905

- MorrowMProgress in the surgical management of breast cancer: present and futureBreast201524Suppl 2S2S526249120

- SagenAKaaresenRSandvikLThuneIRisbergMAUpper limb physical function and adverse effects after breast cancer surgery: a prospective 2.5-year follow-up study and preoperative measuresArch Phys Med Rehabil201495587588124389401

- RaoRThe evolution of axillary staging in breast cancerMo Med2015112538538826606821

- RubioITSentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer: work in progressEur J Surg Oncol201642332633226774943

- KuehnTBembenekADeckerTConsensus Committee of the German Society of SenologyA concept for the clinical implementation of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with breast carcinoma with special regard to quality assuranceCancer2005103345146115611971

- VeronesiUPaganelliGVialeGSentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: results in a large seriesJ Natl Cancer Inst199991436837310050871

- LiCZZhangPLiRWWuCTZhangXPZhuHCAxillary lymph node dissection versus sentinel lymph node biopsy alone for early breast cancer with sentinel node metastasis: a meta-analysisEur J Surg Oncol201541895896626054706

- SoranAOzmenTMcGuireKPThe importance of detection of subclinical lymphedema for the prevention of breast cancer-related clinical lymphedema after axillary lymph node dissection; a prospective observational studyLymphat Res Biol201412428929425495384

- ZurridaSVeronesiUMilestones in breast cancer treatmentBreast J201521131225494903

- BassoSMChiaraGBLumachiFSentinel node biopsy in early breast cancerMed Chem201612327327926567617

- BertozziSLonderoAPThe sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer over the yearsEur J Gynaecol Oncol2016371131627048102

- KimJYKimMKLeeJESentinel lymph node biopsy alone after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with initial cytology-proven axillary node metastasisJ Breast Cancer2015181222825834607

- KibarSDalyan ArasMÜnsal DelialioğluSThe risk factors and prevalence of upper extremity impairments and an analysis of effects of lymphoedema and other impairments on the quality of life of breast cancer patientsEur J Cancer Care (Engl) Epub2016113

- AhmedMRubioITKovacsTKlimbergVSDouekMSystematic review of axillary reverse mapping in breast cancerBr J Surg2016103317017826661686

- SzubaAShinWSStraussHWRocksonSThe third circulation: radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphedemaJ Nucl Med2003441435712515876

- DiSipioTRyeSNewmanBHayesSIncidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet Oncol201314650051523540561

- GebruersNVerbelenHDe VriezeTCoeckDTjalmaWIncidence and time path of lymphedema in sentinel node negative breast cancer patients: a systematic reviewArch Phys Med Rehabil20159661131113925637862

- RebegeaLFirescuDDumitruMAnghelRThe incidence and risk factors for occurrence of arm lymphedema after treatment of breast cancerChirurgia (Bucur)20151101333725800313

- De GournayEGuyomardACoutantCImpact of sentinel node biopsy on long-term quality of life in breast cancer patientsBr J Cancer2013109112783279124169352

- HelyerLKVarnicMLeLWLeongWMcCreadyDObesity is a risk factor for developing postoperative lymphedema in breast cancer patientsBreast J2010161485419889169

- MehraraBJGreeneAKLymphedema and obesity: is there a link?Plast Reconstr Surg20141341154e160e

- BrittonTBSolankiCKPinderSEMortimerPSPetersAMPurushothamADLymphatic drainage pathways of the breast and the upper limbNucl Med Commun200930642743019319006

- BonetiCKorourianSBlandKAxillary reverse mapping: mapping and preserving arm lymphatics may be important in preventing lymphedema during sentinel lymph node biopsyJ Am Coll Surg2008206510381042 discussion 1042–104418471751

- HanJWSeoYJChoiJEKangSHBaeYKLeeSJThe efficacy of arm node preserving surgery using axillary reverse mapping for preventing lymphedema in patients with breast cancerJ Breast Cancer2012151919722493634

- NoguchiMAxillary reverse mapping for breast cancerBreast Cancer Res Treat2010119352953519842033

- ThompsonMKorourianSHenry-TillmanRAxillary reverse mapping (ARM): a new concept to identify and enhance lymphatic preservationAnn Surg Oncol20071461890189517479341

- BourgeoisPLeducOLeducAImaging techniques in the management and prevention of posttherapeutic upper limb edemasCancer19988312 Suppl American280528139874402

- BakerJLPuMTokinCAComparison of [(99m)Tc]tilmanocept and filtered [(99m)Tc]sulfur colloid for identification of SLNs in breast cancer patientsAnn Surg Oncol2015221404525069859

- ClémentOLucianiAImaging the lymphatic system: possibilities and clinical applicationsEur Radiol20041481498150715007613

- Van Den BergNSBuckleTKleinjanGIHybrid tracers for sentinel node biopsyQ J Nucl Med Mol Imaging201458219320624835293

- SarriAJMoriguchiSMDiasRPhysiotherapeutic stimulation: early prevention of lymphedema following axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer treatmentExp Ther Med20101114715223136607

- Schmidt-HansenMBromhamNHaslerEReedMWAxillary surgery in women with sentinel node-positive operable breast cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysesSpringerplus201658526848425

- BonneauCHequetDEstevezJPPougetNRouzierRImpact of axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer who do not fit the Z0011 ACOSOG trial because of three or more metastatic sentinel lymph nodesEur J Surg Oncol2015418998100425986854

- ChenSLiuYHuangLChenCMWuJShaoZMLymph node counts and ratio in axillary dissections following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: a better alternative to traditional pN stagingAnn Surg Oncol2014211425024013900

- PetrelliFLonatiVBarniSAxillary dissection compared to sentinel node biopsy for the treatment of pathologically node-negative breast cancer: a meta-analysis of four randomized trials with long-term follow upOncol Rev201262e2025992218

- McLaughlinSABagariaSGibsonTTrends in risk reduction practices for the prevention of lymphedema in the first 12 months after breast cancer surgeryJ Am Coll Surg20132163380389 quiz 511–51323266421

- de OliveiraMMSarianLOGurgelMSLymphatic function in the early postoperative period of breast cancer has no short-term clinical impactLymphat Res Biol 20162016144220225

- BernaudinJFKambouchnerMLacaveRLa circulation lymphatique, structure des vaisseaux, développement, formation de la lymphe. Revue générale [Lymphatic vascular system, development and lymph formation. Review]Rev Pneumol Clin201369293101 French [with English abstract]23474100

- CelebiogluFPerbeckLFrisellJGröndalESvenssonLDanielssonRLymph drainage studied by lymphoscintigraphy in the arms after sentinel node biopsy compared with axillary lymph node dissection following conservative breast cancer surgeryActa Radiol200748548849517520423

- LachancePAHazenASevick-MuracaEMLymphatic vascular response to acute inflammationPLoS One201389e7607824086691

- AebischerDIolyevaMHalinCThe inflammatory response of lymphatic endotheliumAngiogenesis201417238339324154862

- DieterichLCSeidelCDDetmarMLymphatic vessels: new targets for the treatment of inflammatory diseasesAngiogenesis201417235937124212981

- MillerCLSpechtMCSkolnyMNSentinel lymph node biopsy at the time of mastectomy does not increase the risk of lymphedema: implications for prophylactic surgeryBreast Cancer Res Treat2012135378178922941538