Abstract

Purpose

While fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression often co-occur in breast cancer patients, treatment efficacy for this symptom cluster is unknown. A systematic review was conducted to determine whether there are specific interventions (ie, medical, pharmacological, behavioral, psychological, and complementary medicine approaches) that are effective in mitigating the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients, using the Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature (REAL©) process.

Methods

Peer-reviewed literature was searched across multiple databases; from database inception – October 2011, using keywords pre-identified to capture randomized controlled trials (RCT) relevant to the research question. Methodological bias was assessed using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 50 checklist. Confidence in the estimate of effect and assessment of safety were also evaluated across the categories of included interventions via the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) methodology.

Results

The initial search yielded 531 citations, of which 41 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, twelve RCTs reported on all three symptoms, and eight of these were able to be included in the GRADE analysis. The remaining 29 RCTs reported on two symptoms. Studies were of mixed quality and many were underpowered. Overall, results suggest that there is: 1) promising evidence for the effectiveness of various treatment types in mitigating sleep disturbance in breast cancer patients; 2) mixed evidence for fatigue; 3) little evidence for treating depression; and 4) no clear evidence that treatment of one symptom results in effective treatment for other symptoms.

Conclusion

More high-quality studies are needed to determine the impact of varied treatments in mitigating the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients. Furthermore, we encourage future studies to examine the psychometric and clinical validity of the hypothesized relationship between the symptoms in the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster.

Introduction

Treatments for breast cancer presently provide more hope than ever in terms of treating the cancer and reducing mortality. For nearly all women in the US, with the exception of Native American/Alaska Natives, breast cancer mortality continues to decline,Citation1 suggesting that our methods of screening and treatment are steadily improving for breast cancer treatment. While survival rates for breast cancer patients continue to improve, behavioral and psychosocial side effects from breast cancer and its treatment remain a large problem for these patients, impacting their day-to-day functioning as well as quality of life. Among the most common complaints reported by breast cancer patients during and after treatment are fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression. These symptoms have often been found to co-occur in breast cancer populations both during and after treatment.Citation2–Citation4 The co-occurrence of these and other related symptoms in breast and other cancers has spurred lively discussion about the existence of symptom clusters; an area of study that is relatively in its infancy with no consistent clinical or psychometric measurements.Citation5,Citation6

The etiology of each of these symptoms as well as the potential reasons for their co-occurrence is complex, with psychosocial and physical functioning, type of cancer treatment, and medical diagnostic variables all potentially playing roles in both the onset and maintenance of these symptoms. Current evidence suggests that inflammatory and neuroendocrine dysregulation are associated with, and may help perpetuate the co-occurrence of these symptoms within cancer and other populations,Citation7–Citation9 through a process often termed “sickness behavior”.Citation10 Chronic low-grade inflammation (which is thought to be primarily initiated by the cancer and some forms of cancer treatment) facilitates the manifestation of behavioral symptoms including sleep disturbance, fatigue, and depression in the patient. Evidence also suggests that the occurrence and perpetuation of sickness behavior responses to cancer and cancer treatment may be moderated by dispositional factors, including genetic polymorphisms in genes regulating inflammatory responsesCitation11 and premorbid psychosocial functioning.Citation12

While mechanistic research efforts continue to elucidate the pathophysiology underlying the co-occurrence and persistence of these symptoms, there is consistent evidence that a greater number of co-occurrence of symptoms leads to poorer quality of life,Citation13 increased neuropathic pain,Citation14 and impaired overall functioningCitation15 in breast cancer patients. It is therefore important to understand what types of treatments may be most successful not only in treating one symptom, but in potentially successfully treating symptoms that co-occur. Finding interventions that efficiently treat symptom clusters may yield better outcomes for patients as well as lead to greater cost-efficiency in terms of providing interventions that may target more than one symptom.

To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews exploring the treatments for the co-occurring symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in breast cancer patients and survivors. We conducted a systematic review to examine which treatments are the most efficacious for treating the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients. The specific objectives of this review were to: 1) survey the literature on treatments addressing at least two of the three symptoms in the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster; 2) examine and assess the quantity, quality and efficacy based on studies as reported in the literature; 3) characterize the treatments as behavioral, psychosocial, complementary/alternative medicine (CAM), medical, or pharmacological to better compare treatment types; 4) critically evaluate the efficacy and safety of interventions that examined the impact on the three symptoms based on the literature; and 5) identify gap areas that exist in the literature in order to suggest next steps in research based on our analysis of the pooled literature.

Methods

To conduct this systematic review, we utilized the Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature (REAL©; Samueli Institute, Alexandria, VA, USA) methodology, which is an expedient approach for conducting systematic reviews.Citation16,Citation17 REAL© reviews primarily focus on synthesis of peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in the English language, and utilize searching across multiple databases. Details on the REAL© methodology for this review are described to follow.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched from database inception through October 2011: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, and PsycINFO. The following four initial searches, as entered into PubMed, were combined to produce the final search: 1) (breast cancer) and (depression or depress* or “negative affect” or “negative mood”); 2) (breast cancer) and (fatigue or “vital exhaustion”); 3) (breast cancer) and (“sleep disturbance” or “insomnia” or “sleep disruption” or sleep); and 4) (breast cancer) and (“symptom cluster”). The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and explosions across the terms were applied where applicable and relevant; where MeSH did not apply, variations of the search strategy were used. As this REAL© focused on the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression cluster components, we considered the terms depressed mood, dysthymia, negative affect, emotional distress and negative mood to be synonymous with depression; insomnia and sleep disruption synonymous with sleep disturbance; and vital exhaustion and cancer-related fatigue synonymous with fatigue. The complete search strategies in each of the databases searched can be obtained by contacting the primary author.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were developed in accordance with the Population, Intervention, Control, and OutcomeCitation18 (PICO) framework. Articles were included if they met the following criteria: 1) RCT study design; 2) population consisting of active patients and/or survivors of breast cancer who participated in any treatment intervention; and 3) included at least two of the three cluster symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression (as defined via the search strategy).

Two screeners (CL, RK) screened titles and abstracts for relevance based on the inclusion criteria. Once sufficient inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s Kappa >88%) was achieved, the screeners screened the remaining articles independently, resolving arising queries through discussion with either the review manager (CC) and/or the subject matter experts (SMEs; SJ, LF).

Quality assessment and data extraction

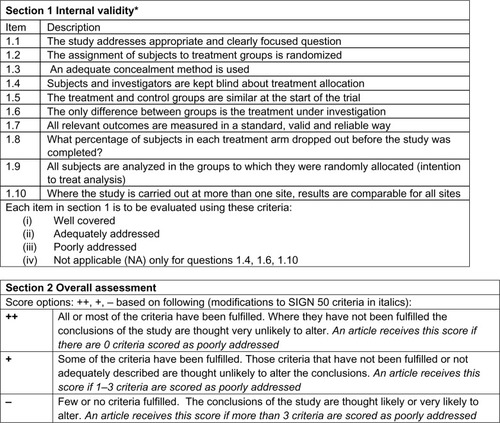

Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by two reviewers (CL, RK) using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 50) checklist for RCTs, a widely accepted, reliable, and validated assessment toolCitation19 (see ). The reviewers were fully trained in the methodology.

Figure 1 SIGN 50 checklist for RCT Study Design.

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

The following information was extracted from each included study: population; initial sample and dropout rates; treatment and control interventions; relevant outcomes and results; the reporting and severity of adverse events; the informed consent process; power calculations; effect sizes; and author’s main conclusions.

Patients were grouped into the following categories: non-metastatic, metastatic, mixed (ie, population included both metastatic and non-metastatic patients), and survivors (those who were no longer receiving active treatment). Treatment interventions were grouped into the following categories: behavioral (eg, exercise), psychosocial (eg, cognitive–behavioral therapy and supportive counseling), CAM (eg, yoga and herbal medicine), medical procedures (eg, radiation, ovarian ablation), or pharmacological (eg, anti-depressants).

Data synthesis and analysis

Once the quality assessment of individual studies was completed, two SMEs (SJ and LF) performed a quality assessment of the overall literature pool for each treatment intervention and patient population using a modified version of the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE), an internationally accepted approach to grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.Citation20 SMEs used the GRADE to examine the results of the review for each population and treatment type in order to: 1) examine the confidence in and magnitude of the estimate of the effect; 2) assign a safety grade; and 3) develop recommendations (such as strong or weak recommendations in favor of or against the use of such treatments) for the included literature pool based on the REAL© results. The SMEs received formal training in the modified GRADE, conducted the GRADE independently, and then met as a team to resolve any discrepancies and come to consensus on overall recommendations.

Results

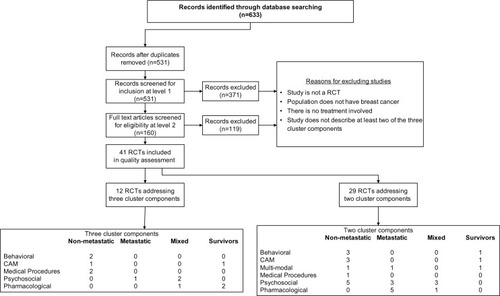

The main objective of this systematic review was to focus on the three symptom cluster for breast cancer. However, due to our comprehensive search strategy, the authors also found several articles that focused on two of the three symptoms. Due to resources and the main objective of this review however, the authors only report on the three symptom cluster in detail assessing the overall literature pool to come up with recommendations using GRADE methodology. The authors share the two symptom cluster studies in as a frame of reference only and hope to perform future analysis of these studies in the future. The studies on two symptoms can be found in Citation21–Citation49 and three symptoms in .Citation50–Citation61

Table 1 Characteristics and SIGN 50 score of included studies, grouped by population and treatment type, that address two cluster components (n=29)

Table 2 Characteristics and SIGN 50 score of included studies, grouped by population and treatment type, that address three cluster components (n=12)

Of the 531 citations yielded from the database searches, 41 RCTs fit the inclusion criteria and were subsequently included in the quality assessment and data extraction phase of the REAL©. Of these, 29 RCTs reported on two component clusters; categorizes these by treatment type and population, and reports their individual characteristics and overall SIGN 50 scores. The remaining twelve RCTs reported on all three component clusters (), eight of which were able to be included in the GRADE analysis ().

Figure 2 Flow chart.

Both and categorize studies according to treatment type (behavioral, CAM, medical procedures, psychosocial, or pharmacological) and across four population types including non-metastatic, metastatic, mixed (comprised of both non-metastatic and metastatic patients), and survivors.

Characteristics of included studies

Methodological quality of included studies according to SIGN 50 criteria

According to SIGN 50 criteriaCitation19 (see ), the majority (63.4%) of the studies received an overall SIGN 50 score of + (high quality), with the remaining (26.8%) articles receiving scores of − (low quality), and fewer (9.8%) receiving a score of ++ (excellent quality).

Most of the 41 RCTs (92.6%) included in the review addressed an appropriate and clearly focused question either well or adequately. Almost half of the articles addressed randomization poorly (46.3%), with 22.0% of articles doing so adequately, and 31.7% doing so well. The majority of articles (65.8%) poorly addressed allocation concealment, with less than a third of articles addressing this criterion either well (22.0%) or adequately (12.2%). Baseline similarities between treatment and control groups were well addressed in the majority of articles (70.7%) with a small percentage of studies addressing it adequately (19.5%) or poorly (9.8%). Outcome reliability and validity was addressed well by 41.4% of articles with the remaining articles addressing this criterion adequately (22.0%) or poorly (36.6%). Although many studies (53.7%) reported attrition rates adequately or well, many articles also poorly addressed intention-to-treat analyses (46.3%).

Three criteria, blinding, treatment group differences, and multi-site differences, were not applicable to all studies (ie, blinding not possible, treatment groups are too inherently different from each other, study only conducted at one site). Consequently, we only assessed the articles where these criteria were applicable. Of the twelve RCTs where blinding was possible, blinding of treatment allocation was addressed well and adequately in 41.7% and 25.0% of the studies, respectively; approximately 33.3% of these studies addressed this criterion poorly. We were able to assess twelve RCTs for treatment difference between groups; many of these articles did so either well (33.3%) or adequately (41.7%), with 25.0% of the articles doing so poorly. Lastly, only a small number of studies (n=12) were conducted at multiple sites; the majority of these poorly addressed (66.6%) similarity of site results, with the remaining articles doing either well (16.7%) or adequately (16.7%).

Safety assessment

Of the 41 articles included in our review, only 16 reported on adverse events with four studiesCitation30,Citation36,Citation46,Citation55 reporting no adverse events. Ten studies reported adverse events including gastrointestinal problems,Citation31,Citation32,Citation43,Citation53 dizziness,Citation31,Citation32 changes in blood pressure,Citation31,Citation34,Citation60 weakness,Citation31 anemia,Citation32 pain/discomfort,Citation24,Citation34,Citation47 headache,Citation43,Citation60 insomnia,Citation53 palpitations,Citation53 anxiety,Citation53 skin rashes and angioedema,Citation51 jaundice/liver damage,Citation51 dry mouth,Citation21 changes in taste,Citation21,Citation51 and disease progression.Citation24 Additionally, two studiesCitation22,Citation23 reported adverse events occurred but did not describe them.

GRADE analysis

The GRADE analysis was conducted on studies addressing all three symptoms (fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression) in order to provide recommendations regarding treatment of the symptom cluster as a whole. While we present the tables on studies that examined two of the three symptoms to familiarize the reader with the breadth of literature available on examining intervention effects on co-occurring symptoms within this cluster, as our primary interest was on examining studies that investigated effects on the symptom cluster as defined by sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and fatigue, we chose to conduct the GRADE on studies that examined these three symptoms. There were twelve RCTs that addressed all three symptoms that were included in this review; of these, one studyCitation50 (examining a psychosocial intervention) reported results in metastatic breast cancer patients, five studies (two examining behavioral interventions,Citation54,Citation55 two examining medical interventions,Citation51,Citation52 and one examining a CAM intervention)Citation53 reported results in non-metastatic breast cancer patients, three studies (two examining psychosocial interventions,Citation57,Citation58 one examining a pharmacological intervention)Citation56 reported results in mixed (metastatic and non-metastatic) breast cancer patients, and three studies (two examining pharmacological interventions,Citation59,Citation60 one examining a CAM intervention)Citation61 reported results on survivors (patients who had completed adjuvant or neo-adjuvant treatment).

Because GRADE analyses require at least two studies per category, only eight of these three RCTs addressing three symptoms were included in the final analysis; four studiesCitation50,Citation53,Citation56,Citation61 were excluded because they were the only studies in their respective categories (ie, CAM treatment for non-metastatic and survivor populations, pharmacological treatment for mixed population, psychosocial treatment for metastatic population).

The GRADE results are presented in and briefly summarized below. In this GRADE synthesis, we noted that most studies did not report effect sizes, nor describe the presence or absence of adverse events. Our final GRADE recommendations, therefore, are given considering these major omissions of reporting in the reviewed studies.

Table 3 GRADE analysis: quality of the overall literature pool by population/intervention type for studies assessing three cluster components

Non-metastatic population

Behavioral treatment

Two studiesCitation54,Citation55 comparing walking exercise programs to usual care in a non-metastatic population, were poor (−) quality and reported improvements in sleep disturbance, but no significant differences for depression. Results were mixed for fatigue symptoms, as one studyCitation55 reported improvement in fatigue levels while the second studyCitation54 reported no such differences. Adverse events were only discussed in one study,Citation55 which reported no adverse events. Because effect sizes were not reported, and both the quality and power of these studies was low, no recommendation could be given for this treatment type.

Medical treatment

Two studiesCitation51,Citation52 examined medical procedures as treatment options for reducing fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in this population. The higher (+) quality study,Citation51 comparing radiotherapy to no radiotherapy, reported improvements in insomnia with radiotherapy, but no significant differences between groups for depression and fatigue. The second studyCitation52 was of poor (−) quality, and compared ovarian ablation with chemotherapy. This study reported lower levels of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in the ovarian ablation versus chemotherapy group. Effect sizes were not reported in either study, and only one studyCitation51 reported adverse events (such as skin rashes, angioedema, taste changes, jaundice, and liver damage). Consequently, a weak recommendation in favor was given for the usage of medical treatment methods for impacting the symptoms examined for this population.

CAM treatment

There was only one study (of high [++] quality)Citation53 examining a CAM treatment in a non-metastatic population. Although fatigue and sleep disturbance symptoms were improved following administration of the herbal compound guarana, no such improvements in depression were found. Adverse events including insomnia, palpitations, nausea, and anxiety were reported. Because this was the only study in this treatment and population category, however, it was not included in the GRADE analysis.

Metastatic population

Psychosocial treatment

One high (+) quality studyCitation50 investigating psychosocial (cognitive behavioral therapy) treatment for metastatic patients reported mixed results for depression, and null results for fatigue and insomnia. Because this was the only study in this population, it could not be examined via GRADE.

Mixed population

Psychosocial treatment

Both studiesCitation57,Citation58 examining psychosocial treatments were of high (+) quality and reported significant improvements in insomnia, no improvements in fatigue and mixed results for depression. Specifically, the first study,Citation57 comparing psychosocial support with either a nurse or psychologist to usual care, found significant improvements in insomnia, but no differences for fatigue or depression symptoms. The second studyCitation58 compared cognitive behavioral therapy to a wait list control. Results showed improvements in both insomnia and depression, but no differences in fatigue. Adverse events were not reported in either study. Given the promising results for sleep improvement in these adequate quality studies, but a lack of information on adverse events, a weak recommendation in favor of psychosocial treatments was given.

Medical treatment

Although one high (+) quality studyCitation56 investigating chemotherapy dosages with tamoxifen reported lower fatigue and depression with the lower versus higher dose of chemotherapy, because there was only one study in this category, a GRADE recommendation could not be provided for medical treatments for a mixed population.

Survivor population

Pharmacological treatment

One high (+) quality and one poor (−) quality study investigating pharmacological treatments cited mixed results for sleep improvement and no improvement in either fatigue or depression. The higher quality studyCitation60 compared low and high dosages of venlafaxine to placebo and found no signifi-cant differences for any of the cluster symptoms. The poor quality studyCitation59 also did not find differences for depression or fatigue, however, the authors reported improvements in insomnia. Effect sizes were not reported in either of the two studies, and only one studyCitation60 reported an adverse event (ie, hypertension). Consequently, no recommendation could be given.

CAM treatment

One high (+) quality CAM studyCitation61 reported improvements in sleep disturbance and fatigue symptoms of breast cancer survivors following a yoga intervention, but no differences in negative mood. Because this was the only CAM study for a survivor population, however, it was not included in the GRADE analysis.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to identify and systematically evaluate the current literature that examined the impact of interventions for the fatigue–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients and survivors. Of the 41 RCTs included in this review, 29 articles reported on two of the three symptom clusters and twelve reported on all three symptoms. It is important to note that many of these studies did not specify these symptoms as primary aims; in fact, 75% of the studies with three symptoms did not overtly specify the primary aim, and 58% of the studies with two symptoms did not specify the primary aim. Many of the studies assessed fatigue and insomnia via the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-30) subscales; while these subscales are considered reliable and valid, they are not as comprehensive in their measurement as some other scales that focus solely on those respective symptoms.

Our systematic evaluation of the literature concerning quality using the SIGN 50 checklist suggested that overall, studies were of high quality, with over a quarter (n=12) of studies being of poor quality and only a few (n=4) being of very high quality. Studies could generally improve in their reporting of randomization and allocation concealment, as well as ensuring that the reliability and validity of outcomes reported are referenced appropriately. While it is not common practice that subscales of self-report questionnaires are referenced in terms of their reliability and validity, if analyses are conducted and conclusions are to be drawn by authors based on subscale results, we suggest that authors of studies should make reference to the reliability and validity of subscales that they examine. We also note that many studies were limited in their sample size.

Overall GRADE results suggest that, out of the three symptoms we reviewed, the one most likely to improve with treatment is sleep disturbance, with many studies reporting a significant effect on sleep disturbance, regardless of type of intervention. In these studies, sleep disturbance was generally reflected by reduced insomnia, and was generally measured using self-report questionnaires such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and the EORTC-QLQ-30 insomnia subscale. Interventions were generally applied post-surgery, and during the active course of breast cancer treatment (examples are chemotherapy and/or radiation), with duration of treatments ranging from 3 weeks to 2 years, and generally being of about 6 weeks. It is interesting to note that only one study included in the GRADE analysisCitation58 utilized an intervention that specifically targeted insomnia. This suggests that self-reported sleep disturbance is a more easily modifiable target in breast cancer patients undergoing active treatment, regardless of the type of intervention. Breast cancer patients report high levels of sleep disturbance at all stages of the breast cancer experience: before diagnosis, after diagnosis and before cancer treatment, during cancer treatment, and even years after the end of cancer treatment.Citation62 Persistent and pervasive sleep problems are debilitating, exacerbate physical pain and psychological distress, and have been shown to impair the immune system; disrupting inflammation signaling and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) stress response.Citation63 Hence targeting sleep disturbance might be the fastest way to improve quality of life and health in breast cancer patients, ultimately decreasing recurrence and hence increasing longevity. Future research should test the validity of these hypotheses.

Our GRADE results indicated mixed findings for interventions on improving fatigue, and little support for depression. These results suggest that while the clustering of sleep disturbance, fatigue, and depression is common, the successful treatment of one symptom does not necessarily result into adequate treatment of related symptoms. Findings suggested that reduction of fatigue sometimes, but not always, followed successful reduction of insomnia in breast cancer patients. The strong co-morbidity of fatigue and sleep disturbance has been previously noted in terms of its occurrence prior to, during, and after active treatment for cancer, Citation2,Citation64,Citation65 with some studies suggesting some commonality in dysregulation of inflammatory pathwaysCitation9,Citation66,Citation67 associated with fatigue and sleep disturbance during treatment. However, persistent fatigue is also associated with HPA axis dysregulation,Citation7 which may require other forms of intervention in addition to modifying sleep. Results for the concomitant modification of depression along with sleep were not promising. Interestingly, depression was more likely to improve with improvements in fatigue, although generally speaking, depression was the least likely symptom of the three to improve during the study period. This suggests that while depression often occurs with fatigue and sleep disturbance during cancer treatment, it may be harder to treat effectively, especially during the course of breast cancer therapy. These findings echo similar conclusions derived from meta-analyses of psychological and pharmacological therapies for depression, where evidence appears mixed for pharmacotherapy, and while somewhat promising for certain psychosocial approaches, is still relatively limited in certain cancer populations.Citation68,Citation69

We note that the majority of our studies generally focused on interventions of a single modality, such as a sole behavioral (exercise), psychosocial (psychotherapy), complementary medicine (herb), or pharmacological (drug) treatment. It is unknown, however, whether more integrative, multi-modal treatments that focus on all aspects of the person and therefore address more than one symptom at once (ie, a multi-modal or “whole systems” approach) may show more promise in being able to effectively treat the symptom cluster to enable breast cancer patients to achieve and maintain a healthier and more regulated state during and after treatment. Multi-modal treatment options, as compared to single modality treatments, have emerged as an important option in the management of many disorders and have the potential to simultaneously address the dynamic nature of the disease process over time. It is the authors’ recommendation that future studies consider more multi-modal or whole-systems approaches to addressing these types of symptom clusters associated with disease states.

There are limitations associated with this systematic review. First, because this is a Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature, the authors only examined the RCT study designs reported on in the English language to explore this research question. Second, due to the general lack of studies reporting examination of all three symptoms examined in the review, and the challenge of existing studies having inadequate power and lack of adverse events reporting, it is challenging to make recommendations about particular types of interventions for this symptom cluster. While we were able to extract data for the studies that included two of the three symptoms as outcomes, we were unable to conduct the GRADE on studies that reported only two of the three symptoms for this review, and this may be seen as a limitation. However, our primary objective was to determine the impact of interventions that addressed all three components of the targeted symptom cluster of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance. The information from this review may guide further reviews that may choose to examine more specifically the impact of interventions on two of the three symptoms (such as fatigue and sleep disturbance). We encourage researchers in the field to take into consideration where we have noted the quality of reporting can be improved in future studies and some of the interventions, outcomes, and symptom cluster relationships that we have discovered throughout this process to produce powerful results in future work.

Conclusion

In summary, results from our systematic review, using the REAL© process, suggest that among the clustered symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression, sleep disturbance appears to be the symptom that responds best to interventions currently studied, with some studies also showing promise for fatigue. It is unclear whether treatment of sleep disturbance will necessarily result in effective improvements in other symptoms. Results also suggest that compared to sleep disturbance and fatigue, depression may be more difficult to treat for breast cancer patients and that treatment of sleep disturbance and fatigue do not necessarily translate to adequate treatment of depression. We highly recommend that future studies examine the psychometric and clinical validity of the hypothesized relationship among the sleep/fatigue/depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients, including examining the relationships of these symptoms over time. In addition we encourage the development and testing of new treatment modalities, including multi-modal treatments, which may prove to be more efficacious than those presently studied for this cluster of symptoms.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

The authors have not presented this data and information before in any journal. This data was presented in a poster at the MASCC/ISOO International Symposium on Supportive Care in Cancer in June 2012Citation70 as well as at the American Psychosocial Oncology Society in February 2013.Citation71 The authors have no professional relationships with companies or manufacturers who will benefit from the results of this present study. This material is based upon work supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under Award No W81XWH-06-1-0279. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision unless so designated by other documentation.

References

- DeSantisCSiegelRBandiPJemalABreast cancer statistics, 2011CA Cancer J Clin201161640941821969133

- LiuLRisslingMNatarajanLThe longitudinal relationship between fatigue and sleep in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapySleep201235223724522294814

- FiorentinoLRisslingMLiuLAncoli-IsraelSThe Symptom Cluster of Sleep, Fatigue and Depressive Symptoms in Breast Cancer Patients: Severity of the Problem and Treatment OptionsDrug Discov Today Dis Models20118416717322140397

- BowerJEGanzPAIrwinMRKwanLBreenECColeSWInflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism?J Clin Oncol201129263517352221825266

- AktasAWalshDRybickiLSymptom clusters: myth or reality?Palliat Med201024437338520507866

- KirkovaJAktasAWalshDDavisMPCancer symptom clusters: clinical and research methodologyJ Palliat Med201114101149116621861613

- JainSIrwinMRBowerJPsychoneuroimmunology of Fatigue and Sleep Disturbance: The role of Pro-Inflammatory CytokinesSegerstromSOxford Handbook of PsychoneuroimmunologyOxfordOxford University Press2012319340

- MillerAHAncoli-IsraelSBowerJECapuronLIrwinMRNeuroendocrineimmune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol200826697198218281672

- LiuLMillsPJRisslingMFatigue and sleep quality are associated with changes in inflammatory markers in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapyBrain Behav Immun201226570671322406004

- DantzerRO’ConnorJCFreundGGJohnsonRWKelleyKWFrom inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brainNat Rev Neurosci200891465618073775

- Collado-HidalgoABowerJEGanzPAIrwinMRColeSWCytokine gene polymorphisms and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: early findingsBrain Behav Immun20082281197120018617366

- LiuLFiorentinoLNatarajanLPre-treatment symptom cluster in breast cancer patients is associated with worse sleep, fatigue and depression during chemotherapyPsychooncology200918218719418677716

- DoddMJChoMHCooperBAMiaskowskiCThe effect of symptom clusters on functional status and quality of life in women with breast cancerEur J Oncol Nurs201014210111019897417

- Golan-VeredYPudDChemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain and its relation to cluster symptoms in breast cancer patients treated with paclitaxelPain Pract2013131465222533683

- KimHJBarsevickAMBeckSLDudleyWClinical subgroups of a psychoneurologic symptom cluster in women receiving treatment for breast cancer: a secondary analysisOncol Nurs Forum2012391E20E3022201665

- LeeCCrawfordCWallerstedtDThe effectiveness of acupuncture research across components of the trauma spectrum response (tsr): a systematic review of reviewsSyst Rev201214623067573

- YorkACrawfordCWalterAWalterJJonasWCoeytauxRAcupuncture research in military and veteran populations: A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the LiteratureMed Acupuncture2011234229236

- McGowanJSampsonMSystematic reviews need systematic searchersJ Med Libr Assoc2005931748015685278

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s HandbookSIGN2001 Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.htmlAccessed December 31, 2013

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Available from: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/INTRO.HTMAccessed September 28, 2010

- BottomleyABiganzoliLCuferTEuropean Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer GroupRandomized, controlled trial investigating short-term health-related quality of life with doxorubicin and paclitaxel versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Group, Investigational Drug Branch for Breast Cancer and the New Drug Development Group StudyJ Clin Oncol200422132576258615226325

- SvenssonHEinbeigiZJohanssonHHatschekTBrandbergYQuality of life in women with metastatic breast cancer during 9 months after randomization in the TEX trial (epirubicin and paclitaxel w/o capecitabine)Breast Cancer Res Treat2010123378579320680680

- Hakamies-BlomqvistLLuomaMSjöströmJQuality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving either docetaxel or sequential methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil. A multicentre randomised phase III trial by the Scandinavian breast groupEur J Cancer200036111411141710899655

- DielIJBodyJJLichinitserMRMF 4265 Study GroupImproved quality of life after long-term treatment with the bisphosphonate ibandronate in patients with metastatic bone disease due to breast cancerEur J Cancer200440111704171215251160

- GeelsPEisenhauerEBezjakAZeeBDayAPalliative effect of chemotherapy: objective tumor response is associated with symptom improvement in patients with metastatic breast cancerJ Clin Oncol200018122395240510856099

- BordeleauLSzalaiJPEnnisMQuality of life in a randomized trial of group psychosocial support in metastatic breast cancer: overall effects of the intervention and an exploration of missing dataJ Clin Oncol200321101944195112743147

- WilliamsSASchreierAMThe role of education in managing fatigue, anxiety, and sleep disorders in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancerAppl Nurs Res200518313814716106331

- LowCAStantonALBowerJEGyllenhammerLA randomized controlled trial of emotionally expressive writing for women with metastatic breast cancerHealth Psychol201029446046620658835

- TargEFLevineEGThe efficacy of a mind-body-spirit group for women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trialGen Hosp Psychiatry200224423824812100834

- BonnemaJvan WerschAMvan GeelANMedical and psychosocial effects of early discharge after surgery for breast cancer: randomised trialBMJ19983167140126712719554895

- CourneyaKSSegalRJMackeyJREffects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trialJ Clin Oncol200725284396440417785708

- WangYJBoehmkeMWuYWDickersonSSFisherNEffects of a 6-week walking program on Taiwanese women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancerCancer Nurs2011342E1E1320697267

- MockVPickettMRopkaMEFatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatmentCancer Pract20019311912711879296

- ListingMKrohnMLiezmannCThe efficacy of classical massage on stress perception and cortisol following primary treatment of breast cancerArch Womens Ment Health201013216517320169378

- ListingMReisshauerAKrohnMMassage therapy reduces physical discomfort and improves mood disturbances in women with breast cancerPsychooncology200918121290129919189275

- da Costa MirandaVTrufelliDCSantosJEffectiveness of guaraná (Paullinia cupana) for postradiation fatigue and depression: results of a pilot double-blind randomized studyJ Altern Complement Med200915443143319388866

- BergerAMKuhnBRFarrLABehavioral therapy intervention trial to improve sleep quality and cancer-related fatiguePsychooncology200918663464619090531

- CohenMFriedGComparing relaxation training and cognitive-behavioral group therapy for women with breast cancerRes Social Work Prac2007173313323

- BadgerTSegrinCMeekPLopezAMBonhamESiegerATelephone interpersonal counseling with women with breast cancer: symptom management and quality of lifeOncol Nurs Forum200532227327915759065

- SandgrenAKMcCaulKDKingBO’DonnellSForemanGTelephone therapy for patients with breast cancerOncol Nurs Forum200027468368810833696

- DolbeaultSCayrouSBrédartAThe effectiveness of a psycho-educational group after early-stage breast cancer treatment: results of a randomized French studyPsychooncology200918664765619039808

- LindemalmCMozaffariFChoudhuryAImmune response, depression and fatigue in relation to support intervention in mammary cancer patientsSupport Care Cancer2008161576517562086

- RoscoeJAMorrowGRHickokJTEffect of paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil) on fatigue and depression in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapyBreast Cancer Res Treat200589324324915754122

- ThorntonLMAndersenBLSchulerTACarsonWEA psychological intervention reduces inflammatory markers by alleviating depressive symptoms: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trialPsychosom Med200971771572419622708

- SandgrenAKMcCaulKDLong-term telephone therapy outcomes for breast cancer patientsPsychooncology2007161384716862634

- JainSPavlikDDistefanJComplementary medicine for fatigue and cortisol variability in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trialCancer2012118377778721823103

- LeeSAKangJYKimYDEffects of a scapula-oriented shoulder exercise programme on upper limb dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot trialClin Rehabil201024760061320530648

- KimSHShinMSLeeHSRandomized pilot test of a simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivorsOncol Nurs Forum2011382E97E10621356647

- SandgrenAKMcCaulKDShort-term effects of telephone therapy for breast cancer patientsHealth Psychol200322331031512790259

- SavardJSimardSGiguèreIRandomized clinical trial on cognitive therapy for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer: psychological and immunological effectsPalliat Support Care20064321923717066964

- PrescottRJKunklerIHWilliamsLJA randomised controlled trial of postoperative radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery in a minimum-risk older population. The PRIME trialHealth Technol Assess200711311149iii17669280

- GroenvoldMFayersPMPetersenMAMouridsenHTChemotherapy versus ovarian ablation as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: impact on health-related quality of life in a randomized trialBreast Cancer Res Treat200698327528416541325

- de Oliveira CamposMPRiechelmannRMartinsLCHassanBJCasaFBDel GiglioAGuarana (Paullinia cupana) improves fatigue in breast cancer patients undergoing systemic chemotherapyJ Altern Complement Med201117650551221612429

- PayneJKHeldJThorpeJShawHEffect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapyOncol Nurs Forum200835463564218591167

- MockVPickettMRopkaMEFatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatmentCancer Pract20019311912711879296

- van DamFSSchagenSBMullerMJImpairment of cognitive function in women receiving adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose chemotherapyJ Natl Cancer Inst19989032102189462678

- ArvingCSjödénPOBerghJIndividual psychosocial support for breast cancer patients: a randomized study of nurse versus psychologist interventions and standard careCancer Nurs2007303E10E1917510577

- SavardJSimardSIversHMorinCMRandomized study on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part II: Immunologic effectsJ Clin Oncol200523256097610616135476

- FahlénMWallbergBvon SchoultzEHealth-related quality of life during hormone therapy after breast cancer: a randomized trialClimacteric201114116417020196640

- CarpenterJSStornioloAMJohnsSRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials of venlafaxine for hot flashes after breast cancerOncologist200712112413517227907

- CarsonJWCarsonKMPorterLSKeefeFJSeewaldtVLYoga of Awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trialSupport Care Cancer200917101301130919214594

- FiorentinoLAncoli-IsraelSInsomnia and its treatment in women with breast cancerSleep Med Rev200610641942916963293

- VgontzasANChrousosGPSleep, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and cytokines: multiple interactions and disturbances in sleep disordersEndocrinol Metab Clin North Am2002311153612055986

- Ancoli-IsraelSLiuLMarlerMRFatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms prior to chemotherapy for breast cancerSupport Care Cancer200614320120916010529

- Van OnselenCCooperBALeeKIdentification of distinct subgroups of breast cancer patients based on self-reported changes in sleep disturbanceSupport Care Cancer201220102611261922290719

- WangXSShiQWilliamsLAInflammatory cytokines are associated with the development of symptom burden in patients with NSCLC undergoing concurrent chemoradiation therapyBrain Behav Immun201024696897420353817

- KimHJBarsevickAMFangCYMiaskowskiCCommon biological pathways underlying the psychoneurological symptom cluster in cancer patientsCancer Nurs2012356E1E2022228391

- LiMFitzgeraldPRodinGEvidence-based treatment of depression in patients with cancerJ Clin Oncol201230111187119622412144

- OsbornRLDemoncadaACFeuersteinMPsychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analysesInt J Psychiatry Med2006361133416927576

- JainSFiorentinoLLeeCKhorsanRJonasWAre there efficacious treatments for treating Fatigue-Sleep Disturbance-Depression Symptom Cluster In Breast Cancer Patients: A Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature (REAL)MASCC/ISOO 2012 International SymposiumNew York, NYJune 28–30, 2012

- JainSFiorentinoLLeeCCrawfordCKhorsanRJonasWBA Rapid Evidence Assessment (REAL©) of the Literature: Are there efficacious treatments for treating the fatigue-sleep disturbance-depression symptom cluster in breast cancer patients?Paper presented at: American Psychosocial Oncology SocietyHuntington Beach, CAFebruary 13–15, 2013

- CrawfordCWallerstedtDBKhorsanRClausenSSJonasWBWalterJAA systematic review of biopsychosocial training programs for the self-management of emotional stress: potential applications for the militaryEvid Based Complement Alternat Med2013747694 Epub 2013 Sep 2324174982