Abstract

Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) is highly curable with first-line therapy. However, a minority of patients present with refractory disease or experience relapse after completion of frontline treatment. These patients are treated with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), which remains the standard of care with curative potential for refractory or relapsed HL. Nevertheless, a significant percentage of such patients will progress after ASCT, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains the only curative approach in that setting. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of refractory or relapsed HL have provided the rationale for the development of novel targeted therapies with potent anti-HL activity and favorable toxicity profile, in contrast to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Brentuximab vedotin and programmed cell death-1-based immunotherapy have proven efficacy in the management of refractory or relapsed HL, whereas several other agents have shown promise in early clinical trials. Several of these agents are being incorporated with transplantation strategies in order to improve the outcomes of refractory or relapsed HL. In this review we summarize the current knowledge regarding the mechanisms responsible for the development of refractory/relapsed HL and the outcomes with current treatment strategies, with an emphasis on targeted therapies and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Introduction

Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) is the most common malignancy in adolescents and young adults.Citation1 HL is divided into classical HL (cHL) accounting for 95% of cases and nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL, which is less common. The cHL subtype is defined by the presence of neoplastic cells of B-cell origin expressing CD30 and CD45, including mononucleated Hodgkin cells and multinucleated Reed–Sternberg (RS) cells, which are in direct interaction with an inflammatory microenvironment consisting of granulocytes, mast cells, T and B lymphocytes, plasma cells and fibroblasts.Citation2 The cross talk between cancer cells and microenvironment is critical for the pathogenesis and progression of HL.Citation3,Citation4

First-line chemotherapy and/or radiation for cHL in patients with advanced disease is associated with cure rates between 70% and 75%.Citation5,Citation6 However, 25%–30% of patients either have primary refractory disease or will relapse following first-line therapy.Citation7 Salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard of care for these patient groups. However, only a subset of patients with primary refractory or relapsed HL achieves long-term progression-free survival (PFS) with this approach, and the prognosis is influenced by the presence or absence of certain risk factors.Citation8,Citation9 Patients who progress or relapse after ASCT have poor prognosis with a median survival of 12–29 months.Citation10,Citation11 Thus, development of novel therapeutic approaches is critical for the treatment of relapsed or refractory HL. The antibody–drug immunoconjugate targeting CD30, named brentuximab vedotin, and immunotherapies targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor represent the most promising new therapies,Citation12,Citation13 while several promising agents are in development or in early clinical trials. However, to date, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHCT) remains the only potentially curative approach for relapsed or recurred disease.Citation14

The purpose of this review is to summarize recent data regarding the molecular mechanisms implicated in the development of refractory or relapsed HL and novel therapeutic approaches for the management of patients failing frontline therapy.

Mechanisms involved in the development of refractory and relapsed HL

The role of microenvironment

In contrast to most other neoplastic diseases, the non-neoplastic cells of the tumor microenvironment outnumber the neoplastic cells in HL, and the distribution of these cells may contribute to the emergence of resistance to conventional therapy.Citation15,Citation16

Macrophages

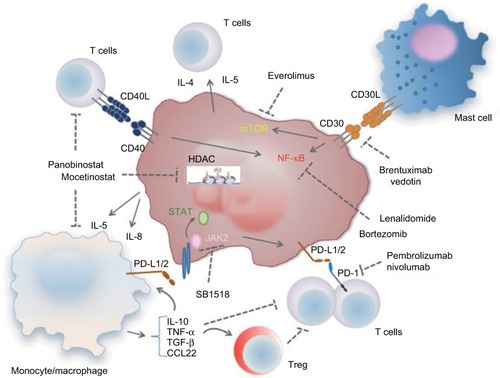

Infiltration of the cHL microenvironment by CD68+ macrophages is considered a negative predictor of PFS for cHL after induction with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) treatment with or without radiotherapy, independent of the International Prognostic Score.Citation17 High numbers of CD68+ and CD163+ macrophages in cHL are associated with worse overall survival (OS), but they also correlate with the presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in the neoplastic cellsCitation18 which, in turn, has been associated with worse outcomes mainly in older individuals.Citation19,Citation20 The exact mechanism underlying the negative impact of macrophages on the above-described outcomes has not been fully elucidated, but it is believed that these cells have an immunosuppressive role and, therefore, may hamper the antitumor immune responses (). In support of this hypothesis, macrophages in the tumor microenvironment can inhibit the response of T cells by releasing various immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β.Citation21 Moreover, TNF-α and IL-10 secretion from monocytes induces the expression of PD-L1 by the same cells in an autocrine manner, leading to decreased T-cell activity and proliferation.Citation22 Tumor-associated macrophages are also known to secrete CCL22, which promotes the trafficking of regulatory T (Treg) cells in the tumor microenvironments through the activation of CCL22/CCR4 axis.Citation23 In turn, Treg cells inhibit antitumor T-cell responses, further supporting the immunosuppressive role of macrophages in the microenvironment of cHL.

Figure 1 Dysregulation of the TME involved in the development of refractory/relapsed HL and targets of novel compounds targeting the TME or the malignant cells.

Abbreviations: HL, Hodgkin’s lymphoma; Treg, regulatory T; PD-L1/2, programmed cell death-L1/2; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TME, tumor microenvironment; HDAC, histone deacetylases.

T cells

The presence of Treg and CD4+ T cells, especially with Th2 phenotype, in the tumor microenvironment has been associated with worse prognosis likely through immune escape.Citation24 Higher density of Treg cells and decreased density of cytotoxic T cells correlate with poorer PFS and OS in patients with cHL.Citation25 Moreover, higher CD4/CD8 ratio in the tumor microenvironment is an independent factor for ABVD treatment failure in patients with HL.Citation26

Interactions between HL and cells of the microenvironment

The interactions between the neoplastic cells and the cells of the microenvironment play a critical role in the development of refractory or relapsed HL. RS cells produce various Th2 and Treg cell chemoattractive cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10Citation27,Citation28; CCL22 and CCL5Citation29 and also cytokines with macrophage chemotactic activity, such as IL-5 and IL-8.Citation30 The recruitment of these cells is reinforced by the reactive cells themselves and particularly macrophages secreting CCL-3, CCL-4 and CCL-8.Citation31,Citation32 Similarly, the neoplastic cells secrete TNF-α and TGF-β promoting the activation of fibroblasts.Citation33,Citation34 In turn, collagen IV produced by fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment is recognized by the DDR1 receptor in RS cells,Citation35 which is a tyrosine kinase promoting the survival and proliferation of these cells.Citation36 These mechanisms generate a vicious cycle between the neoplastic cells and particular components of the microenvironment, promoting resistance to treatment and disease progression. The inflammatory cells of the tumor microenvironment express surface antigens that act as survival signals for the neoplastic cells. These include CD40L expressed on T cells and CD30L expressed on masts cells, and bind the CD40 and CD30 receptors, respectively, which are expressed on RS and Hodgkin cells ().Citation30,Citation37 CD40L:CD40 signaling leads to increased survival of Hodgkin cells and disease progression.Citation38 CD40 ligation inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis of Hodgkin cells potentially promoting the development of resistant disease.Citation39 CD40 also promotes the upregulation of IRF4/MUM1 expression through the activation of NF-κB.Citation40,Citation41 Addition of sCD40L in cultures of Hodgkin cells protects them from the apoptotic effect of bortezomib by downregulating IRF4,Citation42 which acts as a survival factor. CD40-mediated activation can promote the survival and growth of Hodgkin and RS cells via ERK phosphorylation and might be involved in the contact and interaction of the malignant cells with activated cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment creating a positive feedback loop that leads to Hodgkin and RS cell expansion.Citation43,Citation44 Similarly, CD30L expressed on mast cells of the tumor microenvironment interacts with CD30 on the surface of RS cells and leads to activation of NF-κB signaling, resulting in increased cell survival, proliferationCitation45 and secretion of cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α.Citation46

These signaling events and secreted factors have a significant effect in the cellular composition of the tumor microenvironment and the development of refractory and relapsed HL.

Aberrant activation of signaling pathways in HL cells

Several oncogenic pathways have been implicated in the development of disease resistance and progression. As mentioned earlier, aberrant activation of NF-κB is a hallmark of HL cell linesCitation47 as well as primary RS and Hodgkin cells.Citation48 Activation of IKK via upregulation of TRAF is one of the main mechanisms implicated in the activation of NF-κB in HL.Citation49 Oligomerization of CD30 molecules recruits TRAFs leading to IKK activation and subsequent NF-κB upregulation.Citation50 Gain-of-function mutations in positive regulators of NF-κB such as BCL3 and inactivating mutations of its negative regulators such as TNFAIP and NFKBIA have been identified with high frequency in HL.Citation24 Activation of NF-κB in HL promotes cell cycle progression by upregulation of cyclins D1 and D2,Citation51 c-mycCitation52 and c-myb,Citation53 and inhibits apoptosis by induction of antiapoptotic molecules such as BCL-XL Citation54 and c-FLIP.Citation55 NF-κB also promotes secretion of various cytokines such as CCL5, CCL7 and IL-6 by Hodgkin cells, which not only act as autocrine promoters of cancer cell proliferation but also alter the tumor microenvironment by regulating the trafficking of macrophages.Citation24

PI3K pathway signaling alterations have been identified in HL, and the efficacy of PI3K, Akt and mTOR inhibitors in HL is currently under evaluation. INPP5, a PI3K inhibitor, is silenced in HL cells,Citation56 PI3K activation has been implicated in the development of resistance to brentuximab vedotin, while inhibition of PI3K by TGR-1202 increases the efficacy of the drug by promoting mitotic arrest.Citation57 STAT proteins are activated in RS and Hodgkin cells.Citation58 and are essential for their survival and proliferation.Citation59,Citation60 Moreover, JAK2 rearrangements leading to constitutive JAK2 activation and STAT signaling are recurrent in cHL,Citation61 while inhibitors of this pathway, such as lestaurtinib, induce apoptosis in HL cell lines.Citation62 Nonsense, missense and frameshift mutations of PTPN1, a negative regulator of JAK–STAT signaling, are observed in a high percentage of HL cell lines and HL cases,Citation63 while HSP90 is critical for the activation of JAK–STAT signaling in HL cells.Citation64 Importantly, selective amplification of the 9p24.1 chromosome region is associated with simultaneous amplification of PD-L1 and JAK2. As a consequence, the enhanced JAK–STAT signaling further promotes the expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in Hodgkin cells,Citation65 thereby inhibiting T-cell activation and antitumor immunity. Coexpression of PD-L1 and PD-1 in the HL microenvironment serves as an independent poor prognostic factor,Citation66 while a subgroup analysis demonstrated that the prognostic value of PD-1 is significant for patients with limited-stage cHL.Citation67

EBV infection

Monoclonal EBV infection occurs in 40% of cHL and up to 90% of HIV-related HLs suggesting that EBV may be implicated in oncogenic signaling. Indeed, EBV-infected HL cells overexpress LMP1, which leads to constitutive activation of TNF-α receptor, NF-κB signaling and protection from apoptosis.Citation68 The absence of mutations of IκBα, a suppressor of NF-κB activation, in EBV-positive HL cells suggests that EBV activates an alternate (non-IκBα-dependent) mechanism of NF-κB activation.Citation69 EBV-infected HL cells overexpress LMP2 which induces the upregulation of E2F, EBF and Pax-5, promoting cell survival and proliferation.Citation70 Despite the confirmed overexpression of oncogenes encoded in the EBV genome in Hodgkin and RS cells, studies regarding the impact of EBV infection on prognosis and response to treatment are inconclusive.

Novel therapeutic approaches for primary refractory and early relapsed HL

Advancements in the understanding of HL pathophysiology have led to the development of novel therapeutic approaches for the management of relapsed or refractory disease. Compounds that have been evaluated in clinical trials for this purpose include agents targeting the oncogenic signaling in the neoplastic cells or the tumor microenvironment ().

Table 1 Novel agents for relapsed/refractory HL

Targeting the malignant cells

Multiple oncogenic pathways are upregulated in HL cells, including CD30 downstream signaling pathways, JAK– STAT and PI3K–Akt–mTOR. Compounds individually targeting these signaling pathways as single agents or as part of combinational approaches have generated promising results, especially in patients with refractory or relapsed disease.

Brentuximab vedotin, an antibody–drug immunoconjugate targeting CD30, has demonstrated high efficacy in cHL.Citation71 In a Phase I trial including 45 patients with refractory or relapsed HL, the objective response at the maximum tolerated dose was 50% with a median duration of 10 months, whereas 86% of evaluable patients had some disease regression.Citation12 In a subsequent Phase II clinical trial in patients with relapsed and refractory HL after ASCT, the objective response rate was 75%. Approximately one-third of patients achieved complete response (CR) with a median duration of 20.5 months.Citation72 Moreover, brentuximab vedotin has been used, as a single agent or in combination, as salvage chemotherapy prior to ASCT with low toxicity and promising efficacy.Citation73–Citation75 Similarly, the administration of brentuximab vedotin before alloHCT has been associated with improved 2-year PFS and OS and decreased relapsed rate.Citation76 This is particularly critical for the improvement of outcomes in patients who progress after ASCT and proceed to alloHCT. Administration of brentuximab vedotin after failure of alloHCT was associated with an overall response (OR) rate of 50% and a CR rate of 38% without any differences in the rates of graft versus host disease (GVHD) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation.Citation77 Together, these data strongly suggest that brentuximab vedotin is a promising therapeutic modality for patients with relapsed and refractory HL before or after failure of ASCT. Moreover, administration of brentuximab vedotin before alloHCT may improve transplant outcomes.

The efficacy of a novel JAK2 inhibitor, SB1518, was evaluated in 34 patients with relapsed or refractory HL or non-HL demonstrating CR in 4 patients and partial response (PR) in 15 patients.Citation78 The mTOR inhibitor everolimus as single agent is associated with an OR rate of 47% and PR in 42% of patients.Citation79 These clinical outcomes strongly support the conclusion that therapeutic targeting of oncogenic pathways in HL cells represents a promising treatment approach in patients with relapsed or refractory disease. Moreover, the combination of such targeted therapies with chemotherapy during early stages of disease warrants further investigation.

It should be noted that not all molecular/immunological aberrations of HL neoplastic cells are amenable to targeted therapies. Although some RS cells – as well as infiltrating lymphocytes – express CD20, the use of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in combination with chemotherapy has not provided clinical benefit for the treatment of cHL.Citation80,Citation81 Similarly, CD80, which is expressed on RS cells and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, has also been used as a therapeutic target, but the anti-CD80 monoclonal antibody galiximab did not provide a significant benefit.Citation82

Targeting cellular components of the tumor microenvironment

Given the critical role of the cross talk between the neoplastic cells and the cellular components of the tumor microenvironment, compounds targeting these interactions have shown significant efficacy in HL ().

The efficacy of bortezomib and lenalidomide has been evaluated in patients with advanced HL with a goal to target NF-κB, which is activated by the interactions of cancer cells with components of the tumor microenvironment, as previously discussed. Bortezomib as single agent, or in combination with dexamethasone or gemcitabine, has not shown any significant activity in patients with relapsed or refractory disease,Citation83–Citation85 whereas addition of bortezomib to ifosfamide-based combination regimens led to more encouraging results.Citation86,Citation87 In a Phase II clinical trial, lenalidomide as single agent led to an OR of 19% and a cytostatic OR rate of 33% in heavily pretreated patients with cHL.Citation88 In another study including 46 patients with refractory or relapsed HL after ASCT, lenalidomide in combination with metronomic low-dose cyclophosphamide was associated with an OR rate of 38%, whereas 62% of the patients achieved clinical benefit.Citation89 These conclusions support a beneficial role of lenalidomide potentially in combination with chemotherapy in patients with refractory or relapsed HL. It should be noted, however, that the mechanisms accounting for the antilymphoma effect of lenalidomide in HL have not been fully elucidated and may extend beyond the interference with the NF-κB pathway.

Various clinical studies provide compelling evidence that targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a promising approach for patients with relapsed or refractory HL. Specifically, a recent Phase I clinical trial demonstrated that the PD-1 blocking antibody, nivolumab, has a good toxicity profile. Adverse events of any grade and those of grade 3 occured in 78% and 22% of patients, respectively.Citation13 In this study, objective responses were observed in 20 of 23 patients (87%), although CR was not common (17%).Citation13 Subsequently, a single-arm Phase II clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of nivolumab in patients with HL after failure of ASCT and brentuximab vedotin reported OR in 66.3% of patients.Citation90 Pembrolizumab, a different PD-1 blocking antibody, was recently shown to induce PR in 48% of patients with HL relapsing after ASCT with objective responses in the order of 65%.Citation91 Pembrolizumab was also associated with objective responses in 80% of patients with relapsed/refractory HL who failed previous treatment with brentuximab vedotin. Thus, targeting PD-1/PD-L1 interaction in the tumor microenvironment is a promising therapeutic approach for patients with relapsed and refractory HL.

HDACs are commonly overexpressed or overactivated in neoplastic diseases, and targeting of HDACs has been employed as a novel therapeutic approach in various malignancies including lymphomas.Citation92 In HL, activation of HDACs has been associated with downregulation of B-cell-specific antigens and p21, upregulation of STAT signaling and suppression of caspase pathways.Citation93 In addition, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cHL express high levels of HDACs,Citation94 suggesting that HDAC inhibitors might target not only neoplastic cells but also immune cells of the tumor microenvironment. Recent Phase II clinical trials have demonstrated significant efficacy of HDAC inhibitors in patients with relapsedCitation95 and recurrent HL following ASCT.Citation96 The HDAC inhibitor panobinostat alters the secretion of cytokines including TNF-α and IFN-γ, thus modulating the activity of lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment and promoting cancer cell autophagy and death.Citation97 These panobinostat-mediated cytokine modulations have been recently associated with alterations in PD-1 expression in T cells,Citation98 suggesting that the combination of HDAC inhibitors and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors might be a promising therapeutic approach in HL. Other studies have focused on the combination of HDAC inhibitors with molecules targeting oncogenic signaling in HL including mTOR inhibitors, such as everolimus and sirolimus,Citation99,Citation100 or angiogenesis inhibitors, such as sorafenib.Citation101

Transplantation strategies for refractory or relapsed HL

Outcomes of refractory or relapsed HL treated with conventional dose salvage chemotherapy were historically characterized by transient responses and low probability for long-term remission or cure.Citation102 Although the development of novel targeted therapies with potent activity against HL is promising, long-term outcomes with these agents are not well established. The role of ASCT in refractory and relapsed HL is well established and ASCT remains the standard of care for patients who are candidates for curative therapy. AlloHCT is typically reserved for carefully selected patients who relapse after ASCT. Moreover, several transplantation strategies in the autologous or allogeneic setting have been developed with the goal to further improve outcomes, albeit with variable success ().

Table 2 Transplantation strategies for relapsed/refractory HL

Autologous transplantation (ASCT)

Early experience with the use of high-dose chemotherapy requiring autologous stem cell support for the treatment of relapsed or refractory HL showed promising results.Citation103–Citation105 The British National Lymphoma Investigation compared in a randomized fashion the outcomes of patients with HL relapsing after first-line chemotherapy who were treated either with non-myeloablative doses of carmustine (BCNU), etoposide, cytarabine (Ara-C) and melphalan (mini-BEAM) administered without stem cell support, or with high-dose BEAM conditioning followed by ASCT.Citation106 Event-free survival (EFS) and PFS were significantly improved in the arm treated with BEAM plus ASCT. Similarly, in a study by the German Hodgkin Study Group, 161 patients with relapsed HL were treated with two cycles of non-myeloablative doses of dexamethasone and BEAM (Dexa-BEAM), and the responders were subsequently randomized to two more cycles of either Dexa-BEAM or BEAM followed by ASCT.Citation107 Freedom from treatment failure (FFTF) at 3 years was significantly improved in chemosensitive patients who underwent ASCT compared to those who received conventional chemotherapy, although no significant OS benefit was shown. In both studies, radiotherapy was allowed for patients with residual sites of disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis of these two randomized studies again demonstrated that ASCT was associated with improved PFS (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.35–0.86; p = 0.009), but only a trend toward improved OS (HR = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.41–1.07; p = 0.10),Citation108 most likely due to lack of statistical power. Based on the results of these two randomized controlled trials, high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT has been established as the standard of care for patients with relapsed or refractory HL.

Although the indication of ASCT for patients with relapsed disease is supported by randomized trials, there are no randomized data with regard to the optimal salvage therapy and conditioning regimens. A concern with the use of melphalan-containing salvage regimens, such as mini-BEAM or Dexa-BEAM which were used in the two randomized ASCT trials, is the relatively high treatment-related mortality (TRM) and bone marrow toxicity, which may compromise adequate stem cell collection in preparation for ASCT.Citation109–Citation111 Therefore, alternative chemotherapy regimens incorporating non-cross-resistant agents have been extensively studied as salvage treatment for cytoreduction before ASCT. The combination of ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (ICE) was developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer CenterCitation8,Citation112 and is one of the most commonly used salvage regimens for HL. In a cohort of 65 patients with relapsed/refractory HL, two cycles of ICE given every 2 weeks were associated with an OR rate of 88% and resulted in a long-term EFS of 68% in 57 patients who proceeded to ASCT incorporating involved-field radiation therapy.Citation8 An augmented ICE regimen with intensified doses of ifosfamide and etoposide has also been employed for patients with unfavorable risk factors.Citation74,Citation113 Other commonly used salvage regimens include combinations of platinum agents with cytarabine, such as dexamethasone, cisplatin and cytarabine (DHAP),Citation114 or etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine and cisplatin (ESHAP).Citation115,Citation116 Gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens have also been developed, such as gemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin (GDP),Citation117 gemcitabine and vinorelbine (GV),Citation118 GV with doxorubicin (GVD)Citation119 or ifosfamide, gemcitabine and vinorelbine (IGeV).Citation120 Such gemcitabine-based regimens offer the advantage of outpatient administration, and there is some evidence that may achieve similar response rates and superior PFS compared to mini-BEAM, with less toxicity.Citation111

The advent of new targeted or immunotherapy agents for relapsed/refractory HL (detailed in the “Novel therapeutic approaches for primary refractory and early relapsed HL” section) has been embraced with enthusiasm, because they offer the potential for effective salvage therapy without excessive toxicity, in contrast to conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. There is currently no consensus with regard to the optimal salvage strategy for patients with relapsed/refractory HL. However, given the importance of pretransplant disease status for posttransplant outcomes, it is reasonable to attempt a second non-cross-resistant regimen in patients with inadequate response to first salvage, with the goal to achieve CR prior to ASCT.

A variety of conditioning regimens have been used for ASCT in patients with relapsed or refractory HL, but there is no agreement with regard to optimal regimen. The two Phase III prospective randomized studies that established the role of ASCT in such patients used BEAM conditioning,Citation106,Citation107 which remains one of the most commonly used regimens to date. Other common regimens include cyclo-phosphamide, carmustine and etoposide (CBV) with various dosing modificationsCitation121–Citation125; busulfan-based regimens such as busulfan and cyclophosphamide (BuCy),Citation126 busulfan and melphalan (BuMel),Citation127 busulfan, etoposide and cyclophosphamide (BuCyE)Citation128,Citation129 a or triple alkylator regimen of busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa (BuMelTt).Citation130,Citation131 total body irradiation (TBI) (or total lymphoid irradiation [TLI])-based regimens have also been used as conditioning regimens in previously nonirradiated patientsCitation8,Citation113,Citation123,Citation132,Citation133; however, there has been a swift away from such regimens over time due to concerns for increased associated risk of secondary malignancies and long-term toxicity. Based on registry analyses, BEAM appears to be superior to CBV, TBI-based therapies, or BuCyE as a preparative regimen in patients with HL undergoing ASCT.Citation129,Citation134

Prognostic factors for patients with relapsed/refractory HL undergoing ASCT

Considering different combinations of salvage and conditioning regimens, many single-arm studies or retrospective analyses support the role of ASCT in patients with relapsed and/or refractory HL, which was previously established by two prospective Phase III studies in relapsed HL patients.Citation135–Citation138 Moreover, several such studies have sought to identify prognostic factors for ASCT outcomes. Prognostic factors can be divided into patient-related, disease-related at the time of disease relapse or progression, and factors related to disease status prior to ASCT. Age and performance status are the most important patient-related factors and likely influence the risk of TRM.Citation139–Citation141 Factors at the time of disease relapse or progression that have been associated with clinical outcomes include duration of remission, anemia, B-symptomatology, stage IV disease or extranodal involvement and bulky disease.Citation8,Citation139,Citation140,Citation142–Citation144 Although primary refractory HL is thought to confer worse prognosis, such patients may also derive benefit from ASCT, depending on the risk factors present.Citation145,Citation146

Importantly, pre-ASCT factors such as the number of salvage chemotherapy lines, stage and response to salvage therapy are important prognostic factors for post-ASCT outcomes.Citation138,Citation147 Functional imaging by Gallium scans in the past or, most commonly, by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is preferred over computed tomography (CT) for assessment of response to salvage therapy, because it can differentiate viable tumor from residual fibrotic tissue in patients with PR to therapy by CT.Citation142 Moreover, several groups have shown that normalization of pre-ASCT functional imaging and, in particular, FDG-PET is an independent prognostic factor for post-ASCT risk of relapse, PFS and possibly OS, and may be superior to other risk factors at the time of relapse.Citation141,Citation148–Citation151 These findings were corroborated in a recent meta-analysis.Citation152 Based on the notion that FDG-PET response to salvage therapy is predictive of clinical outcomes, MSKCC has performed two Phase II studies of PET-adapted sequential salvage therapy,Citation74,Citation113 in which patients with relapsed or refractory HL who did not achieve CR to first salvage therapy were switched to a different salvage regimen prior to ASCT. PET-adapted salvage strategies may increase the proportion of patients achieving FDG-PET negativity and consequently leading to higher chances of cure. However, such strategies may be limited by the inadequate sensitivity and specificity of the test.Citation152

ASCT for frontline consolidation of patients with high-risk HL

In view of the improved outcomes of ASCT in relapsed or refractory HL and early data in the preemptive setting,Citation153 subsequent randomized clinical trials tested ASCT as a consolidation strategy for patients with unfavorable high-risk HL in first CR or PR, in comparison with standard induction chemotherapyCitation154,Citation155 or intensified induction with or without radiotherapy.Citation156 Despite the different definitions of adverse risk factors, neither study showed a failure-free or a survival benefit in patients receiving frontline ASCT, suggesting that a large fraction of patients with nonchemorefractory unfavorable HL are cured with standard induction chemotherapy or effectively salvaged with ASCT at the time of relapse. Consequently, despite prior controversy,Citation153,Citation157–Citation159 ASCT is not recommended for frontline consolidation in patients with advanced or high-risk HL responding to induction chemotherapy.

Intensification of salvage and sequential high-dose chemotherapy (SHDCT)

Approximately 30–50% of patients with relapsed or refractory HL undergoing ASCT will eventually develop disease progression after transplant. The risk is influenced by the presence of disease-related risk factors and, possibly, by the type of the conditioning regimen.Citation134,Citation160,Citation161 Some investigators have favored more intensive salvage regimens prior to ASCTCitation135,Citation162 with variable results. However, in the absence of prospective comparative trials, such approaches have not been widely adopted. A Phase III European intergroup study investigated whether SHDCT – consisting of sequential high doses of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and etoposide administered to patients responding to two cycles of ESHAP before BEAM ASCT – might decrease the risk of post-ASCT relapse.Citation163 The intervention was proven toxic without survival benefit. Thus, intensification of conditioning did not lead to improved ASCT outcomes.

Tandem ASCT for relapsed/refractory ASCT

The use of tandem ASCT has also been investigated as a strategy to improve the outcomes in patients with relapsed or refractory HL. In the prospective Phase II GELA/SFGM H96 trial, poor-risk patientsCitation164 received salvage treatment followed by tandem ASCT 45–90 days apart.Citation165 The first conditioning was CBV with mitoxantrone (CBVM) or BEAM, and the second was TBI, cytarabine (Ara-C) and melphalan (TAM) or busulfan, cytarabine (Ara-C) and melphalan (BAM) in patients who had received prior irradiation. Long-term follow-up results of the trial showed 46% and 57% freedom from second failure and OS at 5 years, and 41% and 47% at 10 years, respectively, which were comparably favorable to the historic rates especially in patients not achieving CR to cytoreductive therapy.Citation165,Citation166 Other groups using different salvage and conditioning regimensCitation167,Citation168 have similarly suggested that tandem ASCT may be an effective treatment strategy for primary refractory or poor-risk-relapsed HL. However, in the absence of randomized studies and considering the advent of newer effective agents that can be used for salvage or post-ASCT maintenance, tandem ASCT is not routinely performed and has no role in the management of standard risk patients in particular.

Post-ASCT maintenance

An alternative strategy to improve the outcomes of ASCT consists of the use of post-ASCT consolidation or maintenance. Early attempts with the use of cytotoxic chemotherapyCitation169 or immunotherapeutic agents (rIL-2 and IFN-α)Citation170 were not widely adopted due to lack of efficacy or tolerability. In contrast, the multicenter Phase III AETHERA trial evaluated the use of brentuximab vedotin as post-ASCT maintenance therapy in 329 patients with primary refractory or unfavorable-risk-relapsed HL, defined as <12 month initial remission duration or extranodal involvement prior to salvage chemotherapy.Citation142 Patients were randomized to receive brentuximab vedotin for up to 1 year versus placebo. Patients randomized to the treatment arm had significantly improved 2-year PFS of 63% by independent review compared to 51% in the placebo group. The PFS benefit of brentuximab vedotin maintenance was consistent across subgroups, although less notable in patients who achieved PET-negative remission before ASCT. No OS benefit was observed, but the majority of control patients received brentuximab vedotin at the time of progression. Based on the results of the AETHERA trial, brentuximab vedotin has received FDA approval for post-ASCT maintenance in patients with HL at high risk for relapse or progression. The use of other targeted agents, including HDAC inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors, for consolidation is appealing given the high response rates and favorable side-effect profile of such agents, but their role in this setting remains to be shown.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloHCT)

Patients who relapse after ASCT have poor prognosis and, in general, they are not considered curable with standard chemotherapy.Citation10,Citation14 Perhaps the only exception includes patients with truly localized disease that may be salvaged with radiation.Citation171 A second ASCT may be considered for post-ASCT-relapsed HL patients,Citation172 especially in those who have had a long remission interval following first ASCT. However, alloHCT has been most commonly considered for such patients as a potentially curative intervention.

Early experience with myeloablative (MAC) alloHCT in HL patients was associated with limited success due to high rates of TRM and relapse, likely due to the inclusion of heavily pretreated or advanced HL patients.Citation173,Citation174 Moreover, alloHCT was not found to be superior to ASCT in terms of survival outcomes.Citation175,Citation176 Consequently, alloHCT is not recommenced in lieu of ASCT in the management of relapsed/refractory HL and is reserved for carefully selected medically fit patients relapsing after ASCT.

More recently, reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) alloHCT, commonly with the use of fludarabine and melphalan or BEAM conditioning, with or without in vivo T-cell depletion, has been embraced by many centers due to the lower risk of TRM and is considered the recommended approach for patients with relapsed HL who are candidates for alloHCT.Citation177–Citation181 This recommendation is also supported by a retrospective analysis by the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, which demonstrated significantly lower TRM and improved OS survival with RIC compared to MAC alloHCT.Citation182 Prognostic factors for TRM included chemorefractory disease, poor performance status and age >45 years, whereas PFS and OS determinants included performance status and disease status at transplant.Citation183 However, it should be noted that in a more recent analysis, MAC alloHCT was associated with a nonsignificant improvement in PFS due to somewhat better disease control and decreasing TRM in recent years. Consequently, the issue of conditioning intensity may be revised in the future.Citation184 Despite recent improvements, the optimal conditioning regimen for patients undergoing alloHCT for HL remains undetermined, and relapse continues to be a common cause of treatment failure. Finally, patients who relapse after alloHCT have limited treatment options including donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs), second alloHCT, radiation therapy and palliative chemotherapy, and, in general, their prognosis is grim.Citation185,Citation186

There is conflicting evidence regarding the susceptibility of HL to graft versus lymphoma (GVL) effect, which is more crucial in the setting of RIC alloHCT. In support of a potent GVL effect, some studies have shown high rates of clinical responses in heavily treated allografted HL patients to DLICitation187,Citation188 and a reduction in relapse risk in allografted patients developing acute or chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD).Citation175,Citation182,Citation183 However, a large Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) study showed no association between GVHD and reduction of relapse risk after MAC or RIC alloHCT for HL arguing against a potent GVL effect in these patients.Citation189 Moreover, relapse risk remains high for allografted HL patients (especially in comparison with indolent lymphomas).Citation190

Although most of the alloHCT experience for HL (and other lymphomas) is based on patients transplanted with HLA-matched related or unrelated donors, several patients lack suitable HLA-matched donors. Alternative graft sources including mismatched unrelated donors, haploidentical-related donors and unrelated cord blood have extended allograft access to patients with lymphoma (including HL), with acceptable and largely comparable results to matched unrelated donor transplants.Citation191–Citation193 Similarly, although data specific to HL patient cohorts allografted with alternative donors are more limited, they support the notion that all graft sources can be considered in patients who are felt to be candidates for a potentially curative alloHCT.Citation194–Citation198

In view of the development of novel targeted agents with high activity against HL and favorable side-effect profiles, it is likely that alloHCT may play a lesser role in the management of such patients in the proximate future. Moreover, questions remain unanswered regarding the incorporation and optimal sequence of new agents in the treatment plan, without compromising safety. As an example, brentuximab vedotin has been successfully used prior to allogeneic transplantationCitation199,Citation200 as a single agent or in combination with DLI for post-alloHCT relapse.Citation201,Citation202 In contrast, PD-1 blockade prior to or after alloHCT may exacerbate GVHD due to prolonged or permanent inhibition of pathways with a key role in the induction of self-tolerance.Citation203,Citation204

Summary and future directions

In summary, HL is a highly curable disease, but ~25%–30% of patients will progress during or following first-line chemotherapy and will require further treatment. High-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT remains the standard of care for patients with relapsed or refractory HL who respond to salvage therapy, and affords long-term PFS in ~50% of such patients, but ASCT success varies widely depending on the risk factors present and pre-ASCT disease status. There is presently not enough evidence to support a routine role of upfront ASCT in high-risk HL, SHDCT or tandem ASCT. HL relapsing after ASCT is associated with adverse prognosis, and alloHCT in that setting is the only potentially curative treatment modality, although historically limited by high rates of TRM and associated morbidity. Recent advancements in the understanding of HL pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted therapies with promising efficacy and favorable toxicity profiles have provided hope for improving the outcomes of patients with relapsed or refractory HL. Such novel therapies, including brentuximab vedotin and PD-1 inhibitors, have been successfully incorporated in the current treatment paradigm, specifically as salvage therapy of HL patients relapsing after frontline therapy, as post-ASCT maintenance for relapsed or refractory HL with high-risk features and as bridge therapy prior to ASCT or AlloSCT, either alone or in combination with other agents. Moreover, in view of the promising results of such agents, the role of AlloSCT for the management of relapsed or refractory HL might need to be revised. Nevertheless, although the development of numerous novel agents with activity against HL is exciting, further studies are required to determine their long-term efficacy and the optimal combination or sequence of such therapies, ideally in a risk-adapted fashion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA183605, CA183605S1 and AI098129-01 and by the DoD grant PC140571.

Disclosure

Vassiliki A Boussiotis has patents on the PD-1 pathway licensed by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck, EMD-Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Dako. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HjalgrimHEngelsEAInfectious aetiology of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a review of the epidemiological evidenceJ Intern Med2008264653754819017178

- FossHDReuschRDemelGFrequent expression of the B-cell-specific activator protein in Reed-Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin’s disease provides further evidence for its B-cell originBlood19999493108311310556196

- LiuYSattarzadehADiepstraAVisserLvan den BergAThe microenvironment in classical Hodgkin lymphoma: an actively shaped and essential tumor componentSemin Cancer Biol201424152223867303

- SteidlCConnorsJMGascoyneRDMolecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: increasing evidence of the importance of the microenvironmentJ Clin Oncol201129141812182621483001

- SantoroABonadonnaGValagussaPLong-term results of combined chemotherapy-radiotherapy approach in Hodgkin’s disease: superiority of ABVD plus radiotherapy versus MOPP plus radiotherapyJ Clin Oncol19875127372433409

- EngertAPlutschowAEichHTReduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphomaN Engl J Med2010363764065220818855

- CanellosGPRosenbergSAFriedbergJWListerTADevitaVTTreatment of Hodgkin lymphoma: a 50-year perspectiveJ Clin Oncol201432316316824441526

- MoskowitzCHNimerSDZelenetzADA 2-step comprehensive high-dose chemoradiotherapy second-line program for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin disease: analysis by intent to treat and development of a prognostic modelBlood200197361662311157476

- VivianiSDi NicolaMBonfanteVLong-term results of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell transplant as first salvage treatment for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a single institution experienceLeuk Lymphoma20105171251125920528244

- MoskowitzAJPeralesMAKewalramaniTOutcomes for patients who fail high dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue for relapsed and primary refractory Hodgkin lymphomaBr J Haematol2009146215816319438504

- CrumpMManagement of Hodgkin lymphoma in relapse after autologous stem cell transplantHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program200832633319074105

- YounesABartlettNLLeonardJPBrentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomasN Engl J Med2010363191812182121047225

- AnsellSMLesokhinAMBorrelloIPD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaN Engl J Med2015372431131925482239

- SarinaBCastagnaLFarinaLGruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo OsseoAllogeneic transplantation improves the overall and progression-free survival of Hodgkin lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous transplantation: a retrospective study based on the time of HLA typing and donor availabilityBlood2010115183671367720220116

- AlvaroTLejeuneMSalvadoMTOutcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cellsClin Cancer Res20051141467147315746048

- Alvaro-NaranjoTLejeuneMSalvado-UsachMTTumor-infiltrating cells as a prognostic factor in Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a quantitative tissue microarray study in a large retrospective cohort of 267 patientsLeuk Lymphoma200546111581159116236613

- SteidlCLeeTShahSPTumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphomaN Engl J Med20103621087588520220182

- KamperPBendixKHamilton-DutoitSHonoreBNyengaardJRd’AmoreFTumor-infiltrating macrophages correlate with adverse prognosis and Epstein-Barr virus status in classical Hodgkin’s lymphomaHaematologica201196226927621071500

- ClarkeCAGlaserSLDorfmanRFEpstein-Barr virus and survival after Hodgkin disease in a population-based series of womenCancer20019181579158711301409

- StarkGLWoodKMJackFNorthern Region Lymphoma GroupHodgkin’s disease in the elderly: a population-based studyBr J Haematol2002119243244012406082

- KryczekIZouLRodriguezPB7–H4 expression identifies a novel suppressive macrophage population in human ovarian carcinomaJ Exp Med2006203487188116606666

- KuangDMZhaoQPengCActivated monocytes in peritumoral stroma of hepatocellular carcinoma foster immune privilege and disease progression through PD-L1J Exp Med200920661327133719451266

- CurielTJCoukosGZouLSpecific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survivalNat Med200410994294915322536

- CarboneAGloghiniACastagnaLSantoroACarlo-StellaCPrimary refractory and early-relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: strategies for therapeutic targeting based on the tumour microenvironmentJ Pathol2015237141325953622

- KelleyTWPohlmanBElsonPHsiEDThe ratio of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells to granzyme B+ cytotoxic T/NK cells predicts prognosis in classical Hodgkin lymphoma and is independent of bcl-2 and MAL expressionAm J Clin Pathol2007128695896518024321

- Alonso-AlvarezSVidrialesMBCaballeroMDThe number of tumor infiltrating T-cell subsets in lymph nodes from patients with Hodgkin lymphoma is associated with the outcome after first line ABVD therapyLeuk Lymphoma20175851144115227733075

- ReDKuppersRDiehlVMolecular pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol200523266379638616155023

- SkinniderBFMakTWThe role of cytokines in classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood200299124283429712036854

- KuppersRThe biology of Hodgkin’s lymphomaNat Rev Cancer200991152719078975

- de la Cruz-MerinoLLejeuneMNogales FernandezERole of immune escape mechanisms in Hodgkin’s lymphoma development and progression: a whole new world with therapeutic implicationsClin Dev Immunol2012201275635322927872

- AldinucciDGloghiniAPintoADe FilippiRCarboneAThe classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma microenvironment and its role in promoting tumour growth and immune escapeJ Pathol2010221324826320527019

- PoppemaSImmunobiology and pathophysiology of Hodgkin lymphomasHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program200523123816304386

- AldinucciDLorenzonDOlivoKRapanaBGatteiVInteractions between tissue fibroblasts in lymph nodes and Hodgkin/Reed-Stern-berg cellsLeuk Lymphoma20044591731173915223630

- JundtFAnagnostopoulosIBommertKHodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells induce fibroblasts to secrete eotaxin, a potent chemoattractant for T cells and eosinophilsBlood19999462065207110477736

- XuHRaynalNStathopoulosSMyllyharjuJFarndaleRWLeitingerBCollagen binding specificity of the discoidin domain receptors: binding sites on collagens II and III and molecular determinants for collagen IV recognition by DDR1Matrix Biol2011301162621044884

- CarboneAGloghiniAActivated DDR1 increases RS cell survivalBlood2013122264152415424357706

- BiggarRJJaffeESGoedertJJChaturvediAPfeifferREngelsEAHodgkin lymphoma and immunodeficiency in persons with HIV/AIDSBlood2006108123786379116917006

- AldinucciDGloghiniAPintoAColombattiACarboneAThe role of CD40/CD40L and interferon regulatory factor 4 in Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironmentLeuk Lymphoma201253219520121756027

- MetkarSSNareshKNRedkarAANadkarniJJCD40-ligation-mediated protection from apoptosis of a Fas-sensitive Hodgkin’s-disease-derived cell lineCancer Immunol Immunother19984721041129769119

- AldinucciDCelegatoMBorgheseCColombattiACarboneAIRF4 silencing inhibits Hodgkin lymphoma cell proliferation, survival and CCL5 secretionBr J Haematol2011152218219021114485

- CelegatoMBorgheseCUmezawaKThe NF-kappaB inhibitor DHMEQ decreases survival factors, overcomes the protective activity of microenvironment and synergizes with chemotherapy agents in classical Hodgkin lymphomaCancer Lett20143491263424704296

- CelegatoMBorgheseCCasagrandeNCarboneAColombattiAAldinucciDBortezomib down-modulates the survival factor interferon regulatory factor 4 in Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines and decreases the protective activity of Hodgkin lymphoma-associated fibroblastsLeuk Lymphoma201455114915923647062

- CarboneAGloghiniAGatteiVExpression of functional CD40 antigen on Reed-Sternberg cells and Hodgkin’s disease cell linesBlood19958537807897530508

- ZhengBFiumaraPLiYVMEK/ERK pathway is aberrantly active in Hodgkin disease: a signaling pathway shared by CD30, CD40, and RANK that regulates cell proliferation and survivalBlood200310231019102712689928

- KashkarHHaefsCShinHXIAP-mediated caspase inhibition in Hodgkin’s lymphoma-derived B cellsJ Exp Med2003198234134712874265

- GrussHJUlrichDDowerSKHerrmannFBrachMAActivation of Hodgkin cells via the CD30 receptor induces autocrine secretion of interleukin-6 engaging the NF-kappabeta transcription factorBlood1996876244324498630409

- BargouRCLengCKrappmannDHigh-level nuclear NF-kappa B and Oct-2 is a common feature of cultured Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cellsBlood19968710434043478639794

- BargouRCEmmerichFKrappmannDConstitutive nuclear factor-kappaB-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cellsJ Clin Invest199710012296129699399941

- KrappmannDEmmerichFKordesUScharschmidtEDorkenBScheidereitCMolecular mechanisms of constitutive NF-kappaB/Rel activation in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cellsOncogene199918494395310023670

- HorieRWatanabeTMorishitaYLigand-independent signaling by overexpressed CD30 drives NF-kappaB activation in Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cellsOncogene200221162493250311971184

- HinzMKrappmannDEichtenAHederAScheidereitCStraussMNF-kappaB function in growth control: regulation of cyclin D1 expression and G0/G1-to-S-phase transitionMol Cell Biol19991942690269810082535

- DuyaoMPKesslerDJSpicerDBTransactivation of the c-myc promoter by human T cell leukemia virus type 1 tax is mediated by NF kappa BJ Biol Chem19922672316288162911644814

- TothCRHostutlerRFBaldwinASJrBenderTPMembers of the nuclear factor kappa B family transactivate the murine c-myb geneJ Biol Chem199527013766176717706314

- KarinMLinANF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and deathNat Immunol20023322122711875461

- ThomeMTschoppJRegulation of lymphocyte proliferation and death by FLIPNat Rev Immunol200111505811905814

- TiacciEDoringCBruneVAnalyzing primary Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells to capture the molecular and cellular pathogenesis of classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2012120234609462022955914

- LocatelliSLCaredduGInghiramiGThe novel PI3K-delta inhibitor TGR-1202 enhances brentuximab vedotin-induced Hodgkin lymphoma cell death via mitotic arrestLeukemia201630122402240527499137

- SkinniderBFEliaAJGascoyneRDSignal transducer and activator of transcription 6 is frequently activated in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphomaBlood200299261862611781246

- HoltickUVockerodtMPinkertDSTAT3 is essential for Hodgkin lymphoma cell proliferation and is a target of tyrphostin AG17 which confers sensitization for apoptosisLeukemia200519693694415912144

- CochetOFrelinCPeyronJFImbertVConstitutive activation of STAT proteins in the HDLM-2 and L540 Hodgkin lymphoma-derived cell lines supports cell survivalCell Signal200618444945515967637

- Van RoosbroeckKCoxLTousseynTJAK2 rearrangements, including the novel SEC31A-JAK2 fusion, are recurrent in classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2011117154056406421325169

- DiazTNavarroAFerrerGLestaurtinib inhibition of the Jak/STAT signaling pathway in hodgkin lymphoma inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosisPLoS One201164e1885621533094

- GunawardanaJChanFCTeleniusARecurrent somatic mutations of PTPN1 in primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphomaNat Genet201446432933524531327

- SchoofNvon BoninFTrumperLKubeDHSP90 is essential for Jak-STAT signaling in classical Hodgkin lymphoma cellsCell Commun Signal200971719607667

- GreenMRMontiSRodigSJIntegrative analysis reveals selective 9p241 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomaBlood2010116173268327720628145

- PaydasSBagirESeydaogluGErcolakVErginMProgrammed death-1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) expression in Hodgkin lymphomaAnn Hematol20159491545155226004934

- KohYWJeonYKYoonDHSuhCHuhJProgrammed death 1 expression in the peritumoral microenvironment is associated with a poorer prognosis in classical Hodgkin lymphomaTumour Biol20163767507751426678894

- HuenDSHendersonSACroom-CarterDRoweMThe Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) mediates activation of NF-kappa B and cell surface phenotype via two effector regions in its carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domainOncogene19951035495607845680

- JungnickelBStaratschek-JoxABrauningerAClonal deleterious mutations in the IkappaBalpha gene in the malignant cells in Hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Exp Med2000191239540210637284

- PortisTDyckPLongneckerREpstein-Barr Virus (EBV) LMP2A induces alterations in gene transcription similar to those observed in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2003102124166417812907455

- AnsellSMBrentuximab vedotinBlood2014124223197320025293772

- YounesAGopalAKSmithSEResults of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol201230182183218922454421

- ChenRPalmerJMMartinPResults of a multicenter phase II trial of brentuximab vedotin as second-line therapy before autologous transplantation in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201521122136214026211987

- MoskowitzAJSchoderHYahalomJPET-adapted sequential salvage therapy with brentuximab vedotin followed by augmented ifosamide, carboplatin, and etoposide for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a non-randomised, open-label, single-centre, phase 2 studyLancet Oncol201516328429225683846

- KalacMLueJKLichtensteinEBrentuximab vedotin and bendamustine produce high complete response rates in patients with chemotherapy refractory Hodgkin lymphomaBr J Haematol Epub20161216

- ChenRPalmerJMTsaiNCBrentuximab vedotin is associated with improved progression-free survival after allogeneic transplantation for Hodgkin lymphomaBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201420111864186825008328

- GopalAKRamchandrenRO’ConnorOASafety and efficacy of brentuximab vedotin for Hodgkin lymphoma recurring after allogeneic stem cell transplantationBlood2012120356056822510871

- YounesARomagueraJFanaleMPhase I study of a novel oral Janus kinase 2 inhibitor, SB1518, in patients with relapsed lymphoma: evidence of clinical and biologic activity in multiple lymphoma subtypesJ Clin Oncol201230334161416722965964

- JohnstonPBInwardsDJColganJPA Phase II trial of the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in relapsed Hodgkin lymphomaAm J Hematol201085532032420229590

- YounesAOkiYMcLaughlinPPhase 2 study of rituximab plus ABVD in patients with newly diagnosed classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2012119184123412822371887

- KasamonYLJaceneHAGockeCDPhase 2 study of rituximab-ABVD in classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2012119184129413222343727

- SmithSMSchoderHJohnsonJLAlliance for Clinical Trials in OncologyThe anti-CD80 primatized monoclonal antibody, galiximab, is well-tolerated but has limited activity in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: Cancer and Leukemia Group B 50602 (Alliance)Leuk Lymphoma20135471405141023194022

- BlumKAJohnsonJLNiedzwieckiDCanellosGPChesonBDBartlettNLSingle agent bortezomib in the treatment of relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 50206Leuk Lymphoma20074871313131917613759

- TrelleSSezerONaumannRBortezomib in combination with dexamethasone for patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of a prematurely closed phase II study (NCT00148018)Haematologica200792456856917488673

- MendlerJHKellyJVociSBortezomib and gemcitabine in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaAnn Oncol200819101759176418504251

- HortonTMDrachtmanRAChenLA phase 2 study of bortezomib in combination with ifosfamide/vinorelbine in paediatric patients and young adults with refractory/recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma: a Children’s Oncology Group studyBr J Haematol2015170111812225833390

- FanaleMFayadLProBPhase I study of bortezomib plus ICE (BICE) for the treatment of relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaBr J Haematol2011154228428621517809

- FehnigerTALarsonSTrinkausKA phase 2 multicenter study of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2011118195119512521937701

- RuedaAGarcia-SanzRPastorMGotel and GeltamoA phase II study to evaluate lenalidomide in combination with metronomic-dose cyclophosphamide in patients with heavily pretreated classical Hodgkin lymphoma.Acta Oncol201554693393825734915

- YounesASantoroAShippMNivolumab for classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trialLancet Oncol20161791283129427451390

- ArmandPShippMARibragVProgrammed death-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma after brentuximab vedotin failureJ Clin Oncol201634313733373927354476

- LaneAAChabnerBAHistone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapyJ Clin Oncol200927325459546819826124

- BuglioDYounesAHistone deacetylase inhibitors in Hodgkin lymphomaInvest New Drugs201028suppl 1S21S2721127943

- GloghiniABuglioDKhaskhelyNMExpression of histone deacetylases in lymphoma: implication for the development of selective inhibitorsBr J Haematol2009147451552519775297

- YounesAOkiYBociekRGMocetinostat for relapsed classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trialLancet Oncol201112131222122822033282

- YounesASuredaABen-YehudaDPanobinostat in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma after autologous stem-cell transplantation: results of a phase II studyJ Clin Oncol201230182197220322547596

- KleinJMHenkeASauerMThe histone deacetylase inhibitor LBH589 (panobinostat) modulates the crosstalk of lymphocytes with Hodgkin lymphoma cell linesPLoS One2013811e7950224278143

- OkiYBuglioDZhangJImmune regulatory effects of panobinostat in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma through modulation of serum cytokine levels and T-cell PD1 expressionBlood Cancer J20144e23625105535

- LemoineMDerenziniEBuglioDThe pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat induces cell death and synergizes with everolimus in Hodgkin lymphoma cell linesBlood2012119174017402522408261

- ParkHGarrido-LagunaINaingAPhase I dose-escalation study of the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus and the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat in patients with advanced malignancyOncotarget2016741675216753127589687

- LocatelliSLClerisLStirparoGGBIM upregulation and ROS-dependent necroptosis mediate the antitumor effects of the HDACi Givinostat and Sorafenib in Hodgkin lymphoma cell line xenograftsLeukemia20142891861187124561519

- LongoDLDuffeyPLYoungRCConventional-dose salvage combination chemotherapy in patients relapsing with Hodgkin’s disease after combination chemotherapy: the low probability for cureJ Clin Oncol19921022102181732422

- JagannathSDickeKAArmitageJOHigh-dose cyclophosphamide, carmustine, and etoposide and autologous bone marrow transplantation for relapsed Hodgkin’s diseaseAnn Intern Med198610421631683511811

- CrumpMSmithAMBrandweinJHigh-dose etoposide and melphalan, and autologous bone marrow transplantation for patients with advanced Hodgkin’s disease: importance of disease status at transplantJ Clin Oncol19931147047118478664

- ChopraRMcMillanAKLinchDCThe place of high-dose BEAM therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in poor-risk Hodgkin’s disease. A single-center eight-year study of 155 patientsBlood1993815113711458443375

- LinchDCWinfieldDGoldstoneAHDose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin’s disease: results of a BNLI randomised trialLancet19933418852105110548096958

- SchmitzNPfistnerBSextroMGerman Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group; Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow TransplantationAggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trialLancet200235993232065207112086759

- RanceaMMonsefIvon TresckowBEngertASkoetzNHigh-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaCochrane Database Syst Rev20136Cd00941123784872

- DregerPKlossMPetersenBAutologous progenitor cell transplantation: prior exposure to stem cell-toxic drugs determines yield and engraftment of peripheral blood progenitor cell but not of bone marrow graftsBlood19958610397039787579368

- WeaverCHZhenBBucknerCDTreatment of patients with malignant lymphoma with mini-BEAM reduces the yield of CD34+ peripheral blood stem cellsBone Marrow Transplant19982111116911709645585

- KuruvillaJNagyTPintilieMTsangRKeatingACrumpMSimilar response rates and superior early progression-free survival with gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin salvage therapy compared with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan salvage therapy prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin lymphomaCancer2006106235336016329112

- MoskowitzCHBertinoJRGlassmanJRIfosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide: a highly effective cytoreduction and peripheral-blood progenitor-cell mobilization regimen for transplant-eligible patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol199917123776378510577849

- MoskowitzCHMatasarMJZelenetzADNormalization of pre-ASCT, FDG-PET imaging with second-line, non-cross-resistant, chemotherapy programs improves event-free survival in patients with Hodgkin lymphomaBlood201211971665167022184409

- JostingARudolphCReiserMParticipating CentersTime-intensified dexamethasone/cisplatin/cytarabine: an effective salvage therapy with low toxicity in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s diseaseAnn Oncol200213101628163512377653

- AparicioJSeguraAGarceraSESHAP is an active regimen for relapsing Hodgkin’s diseaseAnn Oncol199910559359510416011

- LabradorJCabrero-CalvoMPerez-LopezEESHAP as salvage therapy for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaAnn Hematol201493101745175324863692

- BaetzTBelchACoubanSGemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin is an active and non-toxic chemotherapy regimen in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s disease: a phase II study by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials GroupAnn Oncol200314121762176714630682

- SuyaniESucakGTAkiSZYeginZAOzkurtZNYagciMGemcitabine and vinorelbine combination is effective in both as a salvage and mobilization regimen in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma prior to ASCTAnn Hematol201190668569121072518

- BartlettNLNiedzwieckiDJohnsonJLCancer Leukemia Group BGemcitabine, vinorelbine, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (GVD), a salvage regimen in relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: CALGB 59804Ann Oncol20071861071107917426059

- SantoroAMagagnoliMSpinaMIfosfamide, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine: a new induction regimen for refractory and relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphomaHaematologica2007921354117229633

- ReeceDEBarnettMJConnorsJMIntensive chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, carmustine, and etoposide followed by autologous bone marrow transplantation for relapsed Hodgkin’s diseaseJ Clin Oncol1991910187118791919637

- BiermanPJAndersonJRFreemanMBHigh-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic rescue for Hodgkin’s disease patients following first relapse after chemotherapyAnn Oncol1996721511568777171

- StiffPJUngerJMFormanSJSouthwest Oncology GroupThe value of augmented preparative regimens combined with an autologous bone marrow transplant for the management of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin disease: a Southwest Oncology Group phase II trialBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20039852953912931122

- ArranzRTomasJFGil-FernandezJJAutologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) for poor prognostic Hodgkin’s disease (HD): comparative results with two CBV regimens and importance of disease status at transplantBone Marrow Transplant19982187797869603401

- BenekliMSmileySLYounisTIntensive conditioning regimen of etoposide (VP-16), cyclophosphamide and carmustine (VCB) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaBone Marrow Transplant200841761361918071290

- LaneAAMcAfeeSLKennedyJHigh-dose chemotherapy with busulfan and cyclophosphamide and autologous stem cell rescue in patients with Hodgkin lymphomaLeuk Lymphoma20115271363136621612379

- KebriaeiPMaddenTKazerooniRIntravenous busulfan plus melphalan is a highly effective, well-tolerated preparative regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with advanced lymphoid malignanciesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201117341242020674757

- WadehraNFaragSBolwellBLong-term outcome of Hodgkin disease patients following high-dose busulfan, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and autologous stem cell transplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200612121343134917162217

- FlowersCRCostaLJPasquiniMCEfficacy of pharmacokinetics-directed busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide conditioning and autologous stem cell transplantation for lymphoma: comparison of a multicenter phase II study and CIBMTR outcomesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20162271197120527040394

- BainsTChenAILemieuxAImproved outcome with busulfan, melphalan and thiotepa conditioning in autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaLeuk Lymphoma201455358358723697844

- GangulySJainVDivineCAljitawiOAbhyankarSMcGuirkJBU, melphalan and thiotepa as a preparative regimen for auto-transplantation in Hodgkin’s diseaseBone Marrow Transplant201247231131221460868

- NademaneeAO’DonnellMRSnyderDSHigh-dose chemotherapy with or without total body irradiation followed by autologous bone marrow and/or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results in 85 patients with analysis of prognostic factorsBlood1995855138113907858268

- HorningSJChaoNJNegrinRSHigh-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin’s disease: analysis of the Stanford University results and prognostic indicesBlood19978938018139028311

- ChenYBLaneAALoganBRImpact of conditioning regimen on outcomes for patients with lymphoma undergoing high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20152161046105325687795

- FermeCMounierNDivineMIntensive salvage therapy with high-dose chemotherapy for patients with advanced Hodgkin’s disease in relapse or failure after initial chemotherapy: results of the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte H89 TrialJ Clin Oncol200220246747511786576

- VigourouxSMilpiedNAndrieuJMFront-line high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for high risk Hodgkin’s disease: comparison with combined-modality therapyBone Marrow Transplant2002291083384212058233

- LavoieJCConnorsJMPhillipsGLHigh-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: long-term outcome in the first 100 patients treated in VancouverBlood200510641473147815870180

- CzyzJDziadziuszkoRKnopinska-PostuszuyWOutcome and prognostic factors in advanced Hodgkin’s disease treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation: a study of 341 patientsAnn Oncol20041581222123015277262

- BiermanPJLynchJCBociekRGThe International Prognostic Factors Project score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease is useful for predicting outcome of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantationAnn Oncol20021391370137712196362

- JostingARuefferUFranklinJSieberMDiehlVEngertAPrognostic factors and treatment outcome in primary progressive Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study GroupBlood20009641280128610942369

- JabbourEHosingCAyersGPretransplant positive positron emission tomography/gallium scans predict poor outcome in patients with recurrent/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaCancer2007109122481248917497648

- MoskowitzCHNademaneeAMassziTAETHERA Study GroupBrentuximab vedotin as consolidation therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at risk of relapse or progression (AETHERA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trialLancet201538599801853186225796459

- HahnTMcCarthyPLCarrerasJSimplified validated prognostic model for progression-free survival after autologous transplantation for hodgkin lymphomaBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201319121740174424096096

- PopatUHosingCSalibaRMPrognostic factors for disease progression after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaBone Marrow Transplant200433101015102315048145

- PuigNPintilieMSeshadriTDifferent response to salvage chemotherapy but similar post-transplant outcomes in patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaHaematologica20109591496150220460643

- ShahGLYahalomJMatasarMJRisk factors predicting outcomes for primary refractory hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantationBr J Haematol2016175344044727377168

- SuredaAArranzRIriondoAAutologous stem-cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s disease: results and prognostic factors in 494 patients from the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Transplante Autologo de Medula Osea Spanish Cooperative GroupJ Clin Oncol20011951395140411230484

- MoskowitzAJYahalomJKewalramaniTPretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphomaBlood2010116234934493720733154

- CocorocchioEPeccatoriFVanazziAHigh-dose chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma patients: a reappraisal of prognostic factorsHematol Oncol2013311344022473680

- SmeltzerJPCashenAFZhangQPrognostic significance of FDG-PET in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with standard salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201117111646165221601641

- CastagnaLBramantiSBalzarottiMPredictive value of early 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) during salvage chemotherapy in relapsing/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) treated with high-dose chemotherapyBr J Haematol2009145336937219344403

- AdamsHJKweeTCPrognostic value of pretransplant FDG-PET in refractory/relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma treated with autologous stem cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Hematol201695569570626931115

- CarellaAMCarlierPCongiuAAutologous bone marrow transplantation as adjuvant treatment for high-risk Hodgkin’s disease in first complete remission after MOPP/ABVD protocolBone Marrow Transplant199182991031718517

- FedericoMBelleiMBricePEBMT/GISL/ANZLG/SFGM/GELA Intergroup HD01 TrialHigh-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation versus conventional therapy for patients with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma responding to front-line therapyJ Clin Oncol200321122320232512805333

- CarellaAMBelleiMBricePHigh-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation versus conventional therapy for patients with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma responding to front-line therapy: long-term resultsHaematologica200994114614819001284

- ArakelyanNBerthouCDesablensBEarly versus late intensification for patients with high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma-3 cycles of intensive chemotherapy plus low-dose lymph node radiation therapy versus 4 cycles of combined doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine plus myeloablative chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation: five-year results of a randomized trial on behalf of the GOELAMS GroupCancer2008113123323333018988286

- SuredaAMataixRHernandez-NavarroFAutologous stem cell transplantation for poor prognosis Hodgkin’s disease in first complete remission: a retrospective study from the Spanish GEL-TAMO cooperative groupBone Marrow Transplant19972042832889285542

- FleuryJLegrosMColombatPHigh-dose therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in first complete or partial remission for poor prognosis Hodgkin’s diseaseLeuk Lymphoma19962034259266

- MoreauPFleuryJBricePEarly intensive therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation in advanced Hodgkin’s disease: retrospective analysis of 158 cases from the French registryBone Marrow Transplant19982187877939603402

- MajhailNSWeisdorfDJDeforTELong-term results of autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory or relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphomaBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200612101065107217084370

- SirohiBCunninghamDPowlesRLong-term outcome of autologous stem-cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaAnn Oncol20081971312131918356139

- ShafeyMDuanQRussellJDugganPBaloghAStewartDADouble high-dose therapy with dose-intensive cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cisplatin (DICEP) followed by high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphomaLeuk Lymphoma201253459660221929284

- JostingAMullerHBorchmannPDose intensity of chemotherapy in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol201028345074508020975066

- BricePDivineMSimonDFeasibility of tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) in induction failure or very unfavorable (UF) relapse from Hodgkin’s disease (HD). SFGM/GELA Study GroupAnn Oncol199910121485148810643540

- MorschhauserFBricePFermeCGELA/SFGM Study GroupRisk-adapted salvage treatment with single or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first relapse/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the prospective multicenter H96 trial by the GELA/SFGM study groupJ Clin Oncol200826365980598719018090

- SibonDMorschhauserFResche-RigonMSingle or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first-relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: 10-year follow-up of the prospective H96 trial by the LYSA/SFGM-TC study groupHaematologica2016101447448126721893

- CastagnaLMagagnoliMBalzarottiMTandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory/relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a monocenter prospective studyAm J Hematol200782212212717019686

- FungHCStiffPSchriberJTandem autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with primary refractory or poor risk recurrent Hodgkin lymphomaBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200713559460017448919

- RapoportAPGuoCBadrosAAutologous stem cell transplantation followed by consolidation chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphomaBone Marrow Transplant2004341088389015517008

- NaglerABergerRAckersteinAA randomized controlled multicenter study comparing recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2) in conjunction with recombinant interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) versus no immunotherapy for patients with malignant lymphoma postautologous stem cell transplantationJ Immunother201033332633320445353

- GodaJSMasseyCKuruvillaJRole of salvage radiation therapy for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma who failed autologous stem cell transplantInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys2012843e329e33522672755

- SmithSMvan BesienKCarrerasJSecond autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed lymphoma after a prior autologous transplantBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200814890491218640574

- GajewskiJLPhillipsGLSobocinskiKABone marrow transplants from HLA-identical siblings in advanced Hodgkin’s diseaseJ Clin Oncol19961425725788636773

- AndersonJELitzowMRAppelbaumFRAllogeneic, syngeneic, and autologous marrow transplantation for Hodgkin’s disease: the 21-year Seattle experienceJ Clin Oncol19931112234223508246023