Abstract

Background

Psoriatic arthritis is associated with psychosocial morbidity and decrease in quality of life. Psychiatric comorbidity also plays an important role in the impairment of quality of life and onset of fatigue.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis patients and to correlate it to quality of life indexes, functional capacity, anxiety, depression and disease activity.

Patients and methods

This cross-sectional study was performed on outpatients with psoriatic arthritis. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F; version 4) was used to measure fatigue; 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) to measure quality of life; Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) to assess functional capacity; Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale to measure anxiety and depression symptoms; Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) to evaluate clinical activity.

Results

In all, 101 patients with mean age of 50.77 years were included. The mean PDI score was 8.01; PASI score, 9.88; BASDAI score, 3.59; HAQ score, 0.85; HAD – Anxiety (HAD A) score, 7.39; HAD Depression (HAD D) score, 5.93; FACIT–Fatigue Scale (FACIT-FS) score, 38.3 and CDAI score, 2.65. FACIT-FS was statistically associated with PASI (rs −0.345, p<0.001), PDI (rs −0.299, p<0.002), HAQ (rs −0.460, p<0.001), HAD A (rs −0.306, p=0.002) and HAD D (rs −0.339, p<0.001). The correlations with CDAI and BASDAI were not confirmed. There was statistically significant correlation with all of the domains of SF-36 and FACIT-F (version 4).

Conclusion

Prevalence of fatigue was moderate to intense in <25% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Fatigue seems to be more related to the emotional and social aspects of the disease than to joint inflammatory aspects, confirming that the disease’s visibility is the most disturbing aspect for the patient and that “skin pain” is more intense than the joint pain.

Introduction

Psoriasis (Ps) is a chronic inflammatory disease with worldwide distribution affecting both sexes in the proportion of 1 man:1.3 women, at any age, but more frequently in the 3rd and 4th decades of life. The predisposition seems to be genetically determined and familial occurrence is present in ~30% of cases.Citation1

Psoriatic arthritis (PA) has characteristic features of joint inflammation, with edema, erythema and heat in one or more joints; Moreover, 6%–40% of patients with Ps have arthritis.Citation2–Citation7 The age for the beginning of PA is ~40 years, and patients with severe forms may have earlier manifestation.Citation8

Fatigue is a frequent complaint in patients with arthritis, which they correlate to tiredness.Citation9,Citation10 In humans, fatigue is more central than peripheral, as well as being more psychological than physiological and thus is very difficult to quantify.Citation11,Citation12 It is the result of biochemical and physiological changes and is manifested by weakness, weariness and behavioral disturbances with reduced work capacity or lack of resistance and a subjective feeling of tiredness and discomfort.Citation12–Citation16 There is no detection of actual muscle weakness in most people who complain of fatigue. The fatigued individual cannot handle complex problems and tends to be less reasonable in everyday life and to exhibit inferiority complex, anxiety and depression.Citation12,Citation15,Citation17,Citation18

Multiple factors accelerate the onset of fatigue, including heat, humidity and altitude, while others, such as pleasure, rhythm, motivation, knowledge of the stages of the task to be performed and fitness, delay it. Sex and age also influence the onset of fatigue.Citation12,Citation17

Almost all chronic diseases may evolve with fatigue. The differential diagnosis includes infections; anemia; neoplastic, connective tissue, endocrine, neurological, chronic kidney, chronic liver, metabolic and ionic diseases; sleep and psychiatric alterations; and many others.Citation19–Citation22

Quality-of-life (QoL) health status refers to “dimensions” that are specific and directly related to health conditions, excluding environmental factors, income, beliefs and freedom.Citation23–Citation26

The global well-being of patients and their cohabitants, who experience impairment in QoL of patients and higher levels of anxiety and depression, is markedly worsened by Ps.Citation27 Tezel et alCitation28 studied 80 patients with PA, 40 patients with Ps and 40 healthy subjects in terms of QoL and functional status and found that patients with Ps and PA had worse QoL and patients with PA had worse functional status than healthy individuals.

The severity of Ps is usually assessed only relative to the extent of the skin or joint involvement, leaving aside the assessment of fatigue, QoL and symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, Ps may provoke a negative impact as large as that of debilitating and life-threatening disorders. Such effects include stress, embarrassment, stigma and physical discomfort. Over time, there is an increasing emotional involvement of the patient to the detriment of his/her social life, decreased productivity at school or work and lower self-esteem. Patients believe that fatigue is linked to the disease activity, poor sleep, stress of joint components and lack of sense of well-being, and they consider it more important than the joint symptoms.Citation29,Citation30

The objectives of this investigation were to verify the prevalence of fatigue in patients with PA undergoing treatment at the outpatient clinics of 2 university hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, through the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) tool; to assess the disease activity, QoL, functional capacity and symptoms of depression and anxiety in these patients and, finally, to correlate fatigue with the QoL index, functional capacity, symptoms anxiety and depression, as well as disease activity.

Patients and methods

This was a cross-sectional observational clinical–epidemiological study.Citation31 The research project was approved by the ethical committees of both hospitals: Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ) and Pedro Ernesto University Hospital (State University of Rio de Janeiro – UERJ).

Patients

Patients of both sexes (n=101), aged ≥18 years, with clinical diagnoses based on the 2006 Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR)Citation32 were examined. All patients provided signed informed consent. They were from the Sector of Dermatology (Cutaneous–Articular Diseases Out-Patient Clinic) of the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) and Sector of Rheumatology (Spondiloarthritis Out-Patient Clinic) of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital (State University of Rio de Janeiro). Exclusion criteria were diabetes, liver or kidney failure, hypothyroidism or untreated adrenal insufficiency, neurological diseases from constant muscle activity, myopathy, anemia (hematocrit <30%) and chronic infections, as well as use of medications such as diuretics, beta-blockers, methyldopa and barbiturates. Hospitalized or home-in-bed patients were also excluded.

Methods

Patients who fulfilled the CASPAR were interviewed, and they answered the questionnaires, for which permission for use was obtained from the authors by email. After a brief explanation by one of the health care team members, the following protocols were filled out: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36),Citation33 Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI),Citation30 Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale,Citation34 FACIT-F, FACIT–Fatigue Scale (FACIT-FS)Citation35 and Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ).Citation36 Disease activity was measured with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI),Citation37 Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)Citation38 and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI).Citation39

Statistical evaluation

The 2 × 2 tables were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test. In the remaining contingency tables, the χ2 test was used. In the correlation analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficient r was used. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed with the R software, version 2.11, free and open source code.

Results

Population studied

Three hundred patients with Ps from the Sector of Dermatology of the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, UFRJ (Cutaneous–Articular Diseases Out-Patient Clinic) and 150 patients with spondyloarthritis from the Sector of Rheumatology of the Pedro Ernesto Hospital, UERJ (Spondyloarthritis Out-Patient Clinic) were evaluated, and of them, 101 fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with the following characteristics:

Sex: 57 men (56.4%) and 44 women (43.6%)

Color: 61 Caucasian, 33 mixed and 7 black

Average age: 50.77 years (sd =0.48); minimum: 23 years; maximum: 79 years

Articular disease

The articular disease was clinically and/or radiologically diagnosed and showed the distribution presented in .

Table 1 Distribution of articular involvement

QoL, fatigue, functional capacity and disease activity

The SF-36 tool with 8 domains is presented in . All domains (FC, functional capacity; PAL, physical aspects limitation; GHS, general health status; SA, social aspects; EA, emotional aspects; VIT, vitality) ranged from 0 to 100, except PAIN, whose minimum value was 10, and mental health (MH), whose minimum value was 24.

Table 2 Distribution of SF-36 components

The intermediary values show that all SF-36 domains were impaired by the disease.

There are 4 domains of FACIT-F, as seen in (PW, physical well-being; S/F W, social and family well-being; EW, emotional well-being; FunW, functional well-being and a Fatigue Scale). There are specific scores that add some domains, such as TOI (PW + FunW + Fatigue Scale), G (PW + S/F W + EW + FunW) and F (PW + S/F W + EW + FunW + Fatigue Scale).

Table 3 Distribution of FACIT-F (version 4) components

The FACIT-F domains showed alterations, as did the SF-36 that measures the same variables. The sum of scores (TOI, F and G) also showed alterations.

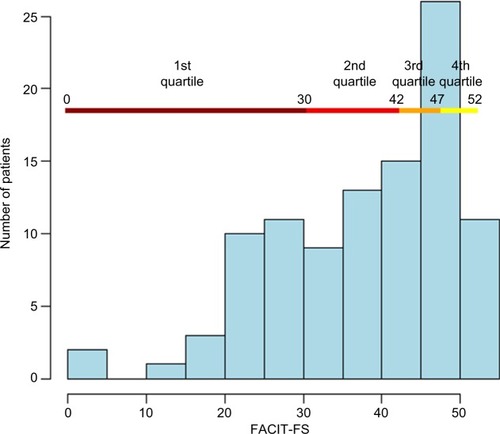

Fatigue was intense to moderate in the 1st quartile (25 patients), as seen in .

Figure 1 Distribution of FACIT-FS scores.

FACIT Scale, PASI, PDI, BASDAI, HAQ, HAD A, HAD D and CDAI scores showed minimum and maximum values as distributed in , which shows the variation of the scores found for fatigue, disease activity, QoL, functional capacity as well as the symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Table 4 Distribution of FACIT-FS, PASI, PDI, BASDAI, HAQ, HAD A/D and CDAI domain values

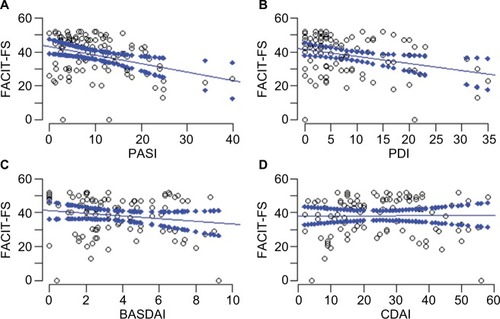

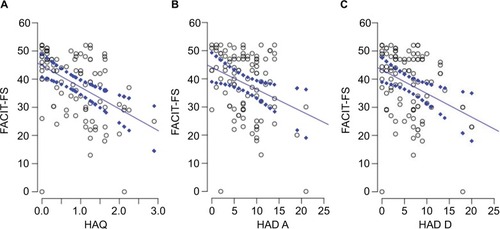

The correlation was strong between the FACIT-FS and the skin disease activity rates, as assessed by PASI; QoL assessed by PDI; and anxiety and depression assessed by HAD. However, the correlations with the peripheral and axial joint disease activity indexes, as assessed by the BASDAI and the CDAI, were not confirmed. and illustrate these findings.

Figure 2 Correlation between FACIT-FS scores and (A) PASI, (B) PDI, (C) BASDAI and (D) CDAI scales.

Abbreviations: FACIT-FS, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue Scale; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PDI, Psoriasis Disability Index; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index.

Figure 3 Correlation between FACIT-FS scores and (A) HAQ, (B) HAD A and (C) HAD D scales.

Abbreviations: FACIT-FS, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue Scale; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HAD A/D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale – Anxiety/Depression.

The correlation was strong between FACIT-F and the different domains of SF-36 that included not only physical and functional aspects but also emotional, social and mental health, ranging below 0.001.

Fatigue Scale scores were correlated with FACIT-F domains, which included not only physical and functional aspects, but also those that assessed emotional and social aspects. There were no correlations with TOI and F score sums because both contain the FACIT Scale.

Discussion

Ps has a high worldwide prevalence and a broad spectrum of cutaneous and articular manifestations, with a negative impact on the QoL, function, indexes of anxiety and depression as well as increased sensation of fatigue, especially in the presence of associated arthritis, and may be associated with decreased survival.Citation40

LomholtCitation41 suggested that the earlier the disease starts in a population, the more the environmental factors involved in its onset are relevant. The low PASI, PDI and fatigue scores in our patients can be credited to the sunny climate of the city of Rio de Janeiro and the daily habits of wearing less clothing and more sun exposure of its inhabitants, and the fact that Rio de Janeiro is one of the happiest cities in the world.Citation42,Citation43

There are no specific indicators to assess the disease activity in PA, or they are still in the process of validation. The tools deployed nowadays for assessing the disease have been insufficiently validated or are borrowed from rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We decided to use the CDAI, unlike other indexes used in RA, which does not include any measure in response to the acute phase response (APR) in its formula. In cases of PA, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) do not assume high values and often bear no relation with the intensity of the inflammation. The CDAI designed for RA may therefore be used in PA and other arthritis models.Citation39

At the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) meetings,Citation44 the possibility of using an already existing measure to evaluate PA or the need to create a new one specific to the disease was discussed several times and their advantages and disadvantages were analyzed.Citation45

Gupta and Gupta Citation46 reported that Ps has a greater impact on the QoL of patients aged between 18 and 45 years, and that men suffer a higher degree of work-related stress due to the disease. These authors did not find any differences between sexes in terms of the disease’s severity.

Sampogna et al,Citation47 in their assessment of hospitalized patients, found that women aged >65 years had a greater reduction in QoL related to Ps. In this study, only patients with arthritis aged >18 years were included, and the PASI average was 9.88 and the PDI average was 8.01, showing that even in this population, the majority of patients showed an impairment that can be considered mild to moderate, corroborating the influence of environmental factors, which was also observed by one of the authors (unpublished data).Citation48

Most studies consider stress a factor significantly related to the worsening of the disease. Each population has specific psychological characteristics. Thus, the manner in which coastal city-dwelling Brazilians deal with stress and how it influences the disease is a relevant topic in the study of Ps.

Various types of questionnaires have been developed in an attempt to assess patients’ QoL, including questions about physical and mental health, as well as aspects related to their family, friends and social life. These questionnaires can be generic or specific to dermatology diseases and these provide scientific and systematic grounds to measure what matters to the patient.Citation49

The variation between the QoL questionnaires is often related to the degree to which they emphasize objective dimensions compared to subjective ones, the extent to which the various areas are covered and the format of questions rather than differences in the definition of QoL.Citation49,Citation50

For this study, the PDI was chosen for including some detailed domains, such as personal relationships, leisure and daily activities, whether at school, at work or in general. Moreover, Japiassu, in 2008,Citation48 noted that PDI and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), widely used for all dermatoses, are reliable and equivalent to evaluate the QoL of Ps patients with or without arthritis.

Studies on fatigue in RA have shown that patients consider their fatigue frustrating and exhausting and that it is much more related to pain intensity, depressed mood and nonrestorative sleep than to the inflammation itself and anemia.Citation9,Citation51–Citation53 For many patients, fatigue is not a disorder, but something expected and normal in their daily routine.Citation54,Citation55

Pollard et alCitation51 concluded that disease activity does not play any role in the level of fatigue and the relation between inflammation and fatigue is not as strong as generally assumed. Psychosocial factors may be important in the perpetuation of fatigue, and some of them may make certain patients more prone to fatigue.

Treharne et alCitation55 stated that psychological factors and depression are major contributors to fatigue, but not the only ones. The pain, the disease activity and the painful joint count were moderately associated, while swollen joints, anemia, ESR and PCR were not. Skin diseases are known to have deleterious effects on the QoL of patients and Ps, considered by many as a psychodermatosis amid its multicausality, presents the psychosocial factor to a relevant extent. Indeed, social and psychological factors are codeterminants of the health–disease process, in a biopsychosocial model, wherein diseases are the result of several factors. The contribution of psychosocial factors varies from disease to disease, from person to person and between worsening episodes in the same person.

It has already been shown that the patients’ vision of Ps is not associated with the severity of the case, suggesting that they respond psychologically more to their own view than to the actual severity of the disease. It explains why it is sometimes not possible to associate the impact of Ps with the severity of the condition, or why this ratio is weak.Citation56

When the domains of QoL are stratified, the most affected in Ps are personal relationships and daily activities, reflecting the stigmatizing burden in patients’ everyday life, particularly in relationships. It is therefore important to evaluate the Ps patient’s perception regarding their health, disability and their QoL, as well as how this perception is associated with the perception of pain and fatigue.

The negative impact of Ps on different QoL domains is comparable to, or even greater than that of, other potentially fatal chronic diseases.Citation57 Patients with severe Ps associated with diabetes, asthma or bronchitis would rather have the underlying disease than the skin disease.Citation25 Many patients, when comparing the involvement of the joint with that of the skin, literally say that the skin bothers them much more than the pain, inflammation and joint deformity.

Studies in patients with Ps show that 3 out of 4 patients avoid sporting or swimming activities because of the disease, one-third of them are inhibited in their sexual relationships and the disease influences career choices in 25%.Citation58,Citation59

Hughes et al Citation60 were the first to demonstrate that dermatological patients, whether outpatients or hospitalized, have higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than the general population. Since then, several studies have been published reporting a prevalence ranging from 14% to 70%,Citation61–Citation64 although causal inferences cannot be made due to their sectional designs. A prospective study with dermatological patients without psychiatric morbidity at the first visit showed an incidence of psychiatric disorders, after 1 month, by 7.6%, with even higher percentages in patients with unsatisfactory treatment results.Citation65 The risk of developing a psychiatric disorder was 3 times higher in patients who did not get better with treatment.Citation64 Magin et alCitation66 demonstrated, in a longitudinal study, evidence that stress and depression, but not anxiety, may play a role in the multifactor etiology of skin diseases. Longitudinal studies are therefore needed to define the correct direction of this association.

Although studies conducted in Western populations have shown that the prevalence of nonpsychotic mental disorders ranges from 7% to 26%, with an average of 17% (12.5% in men and 20% in women), studies show that, in Brazil, this rate can be much higher, ranging from one-third to 50% of patients.Citation67 The average PDI value was 8.4, higher than the value of 7.6 found by Japiassu.Citation48 Such values correlated with fatigue in a statistically significant way.

Although the association between the disease and the presence of symptoms of anxiety and depression was high in the study due to its sectional design, it was not possible to establish the correct causal relationship between both of them and fatigue, with which it was statistically significantly correlated.

Using PDI with HAD and fatigue represents an interesting study strategy, because both deal with issues linked to emotional aspects of the life of patients who have a skin disease.

Minnock et alCitation68 measured fatigue as a sensitive and independent pattern in PA patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF), using a numerical scale from 0 to 10. Fatigue levels were 5.6 (2.3) and 3.6 (2.2) (p=0.001) at the beginning and 3 months later, respectively, and it was found that fatigue was an independent and sensitive measure to assess changes in patients with PA, when compared with HAQ, pain and CRP.

Gladman et alCitation69 assessed the effects of 40 mg of subcutaneous adalimumab every 14 days in terms of functional impairment, QoL, fatigue and pain in patients with PA compared to placebo. The same questionnaires were used and they concluded that the group treated with anti-TNF experienced reductions in their functional limitations, fatigue and pain, along with an improved QoL.

Fatigue was moderate to severe in a quarter of patients, less prevalent than seen in RA,Citation51–Citation53 and correlated with the disease activity and not the cutaneous articular disease, confirming the findings that the visibility of the disease is highly relevant to patients and that the “skin pain” and the “soul pain” are much more intense than the pain and joint inflammation.Citation56

Conclusion

Fatigue was prevalent in patients with PA monitored in the Cutaneous–Articular Diseases Out-Patient Clinic of HUCFF/UFRJ and in the Spondyloarthritis Out-Patient Clinic of HUPE/UERJ. It was intense to moderate in a quarter of patients. The PASI, BASDAI and CDAI indexes were satisfactory in the evaluation of disease activity and were consistent with mild-to-moderate disease intensity in most patients. The HAQ was able to assess patients’ functional capacity, showing that the average inability ranged from mild to moderate, while SF-36, PDI and FACIT-F were able to assess the QoL in its many aspects, showing greater impairment in personal relationships, emotional aspects and daily activities. The fatigue assessed by the FACIT-FS statistically significant correlated the indexes of QoL and the symptoms of anxiety and depression with the disease activity assessed by PASI. There was no correlation, however, with CDAI nor with BASDAI, which measure the articular and axial disease activity. The “skin pain” seems to be more intense than the joint pain.

Final considerations

The study of fatigue in PA is intriguing and leads to several considerations: Is depression a cause or a consequence of the disease and of its severity? Is there a distinct pattern of response to stress in patients with Ps? How to assess it? What is the real influence of environmental factors on fatigue? Is the disease’s visibility the only factor valued by the patient? What is the magnitude of the “skin pain”?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CNPq (National Council of Scientific and Technological Development). The authors hereby state that the current paper is based on the Master’s thesis submitted by Dr Claudio Carneiro, who obtained the title of Master of Sciences from the University of the State of Rio de Janeiro with this thesis.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Van de KerkhofPCMSchelkwijkJPsoriasisBologniaJLJorizzoJLSchafferJVDermatology3rd edLondresElsevier20121351156

- CarneiroSCSOliveiraMLWVianaUMirandaMJSAzulayRDCarneiroCSPsoriasis: a study of osteoarticular involvement in 104 patientsF Med (Br)19941093121125

- AslanianFMLisboaFFIwamotoACarneiroSCClinical and epidemiological evaluation of psoriasis: clinical variants and articular manifestationsJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol200519114114215649217

- GelfandJMGladmanDDMeasePJEpidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United StatesJ Am Acad Dermatol200553457316198775

- MyersWAGottliebABMeasePPsoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: clinical features and disease mechanismsClin Dermatol200624543844716966023

- RobertsMEWrightVHillAGPsoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatmentWorld J Orthop20145453754325232529

- López-FerrerALaiz-AlonsoAPsoriatic arthritis: an updateActas Dermosifiliogr20141051091392224674606

- LiuJTYehHMLiuSYChenKTPsoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatmentWorld J Orthop20145453754325232529

- BianchiWAEliasFRPinheiro GdaRAnalysis of the association of fatigue with clinical and psychological variables in a series of 371 Brazilian patients with rheumatoid arthritisRev Bras Reumatol201454320020725054597

- BianchiWAEliasFRCarneiroSAssessment of fatigue in a large series of 1492 Brazilian patients with spondyloarthritisMod Rheumatol201424698098424884480

- MorrisGBerkMGaleckiPWalderKMaesMThe neuro-immune pathophysiology of central and peripheral fatigue in systemic immune-inflammatory and neuro-immune diseasesMol Neurobiol20165321195121925598355

- CarneiroCChavesMVerardinoGDrummondARamos-e-SilvaMCarneiroSFatigue in psoriasis with arthritisSkinmed201191343721409960

- BelzaBLThe impact of fatigue on exercise performanceArthritis Care Res1994741761807734475

- NikolausSBodeCTaalEvan de LaarMAFour different patterns of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis patients: results of a Q-sort studyRheumatology (Oxford)201049112191219920688805

- BültmannUKantIJKaslSVSchröerKASwaenGMvan den BrandtPALifestyle factors as risk factors for fatigue and psychological distress in the working population: prospective results from the Maastricht Cohort StudyJ Occup Environ Med200244211612411858191

- NierengartenMBACR/ARHP Annual Meeting 2012: Fatigue for people with Rheumatoid Arthritis rooted in Physiological and Psychological FactorsWashingtonThe Rheumatologist32013 issn: 1931-3209

- IshizakiYIshizakiTFukuokaHChanges in mood status and neurotic levels during a 20-day bed restActa Astronaut200250745345911924678

- WesselySPowellRFatigue syndrome: a comparison of chronic “postviral” fatigue with neuromuscular and affective disordersJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19895289409482571680

- KroenkeKWoodDRMangelsdorffADMeierNJPowellJBChronic fatigue in primary care. Prevalence, patient characteristics, and outcomeJAMA198826079299343398197

- BatesDWSchmittWBuchwallDPrevalence of fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in a primary care practiceArch Intern Med199315324275927658257251

- GillilandBFibromialgia, artrite associada a doenças sistêmicas e outras artrites [Fibromyalgia, arthritis associated to systemic diseases and other arthritis]KasperDLBraunwaldEFauciASLongoDLHauserSLJamesonJLHarrison Medicina InternaRio de JaneiroMc Graw Hill200621562165

- BennettRMFibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndromeGoldmanLAusielloDCecil Medicine23rd edNew YorkSaunders200720822083

- GuyattGHEagleDJSackettBMeasuring quality of life in the frail elderlyJ Clin Epidemiol19934612143314448263570

- WilsonIBKaplanSClinical practice and patients’ health status: how are the two related?Med Care1995334 supplAS209AS2147723449

- FinlayAYColesECThe effect of severe psoriasis on quality of life of 369 patientsBr J Dermatol199513222362447888360

- FinlayAYQuality of life measurement in dermatology: a practical guideBr J Dermatol199713633053149115906

- Martínez-GarcíaEArias-SantiagoSValenzuela-SalasIGarrido-ColmeneroCGarcía-MelladoVBuendía-EismanAQuality of life in persons living with psoriasis patientsJ Am Acad Dermatol201471230230724836080

- TezelNYilmaz TasdelenOBodurHIs the health-related quality of life and functional status of patients with psoriatic arthritis worse than that of patients with psoriasis alone?Int J Rheum Dis2015181636924460852

- KirbyBRichardsHLWooPHindleEMainCJGriffithsCEPhysical and psychologic measures are necessary to assess overall psoriasis severityJ Am Acad Dermatol2001451727611423838

- SkoieIMTernowitzTJonssonGNorheimKOmdalRFatigue in psoriasis: a phenomenon to be exploredBr J Dermatol201517251196120325557165

- KleinCHBlochKVEstudos seccionais [Sectional studies]MedronhoRACarvalhoDMBlochKVLuizRRWerneckGLEpidemiologiaSão PauloAtheneu2003125150

- TaylorWGladmanDHelliwellPClassification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international studyArthritis Rheum20065482665267316871531

- HustedJAGladmanDDFarewellVTLongJACookRJValidating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in patients with psoriatic arthritisJ Rheumatol19972435115179058658

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- WebsterKCellaDYostKThe functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretationHealth Qual Life Outcomes200317914678568

- BlackmoreMGGladmanDDHustedJLongJAFarewellVTMeasuring health status in psoriatic arthritis: the Health Assessment Questionnaire and its modificationJ Rheumatol19952258868938587077

- FredrikssonTPetterssonUSevere psoriasis-oral therapy with a new retinoidDermatologica19781574238244357213

- CalinAGarretSWhitelockHA new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function IndexJ Rheumatol19942112228122857699629

- AletahaDSmolenJThe Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritisClin Exp Rheumatol200523suppl 39S100S10816273793

- SalahadeenETorp-PedersenCGislasonGHansenPRAhlehoffONationwide population-based study of cause-specific death rates in patients with psoriasisJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol20152951002100524909271

- FarberEMNallMLThe natural history of psoriasis in 5,600 patientsDermatologica197414811184831963

- GreenburgZIn Pictures: The World’s Happiest Cities. 1Rio de Janeiro, Brazil2009 Available from: www.forbes.com/lastAccessed February 7, 2017

- VazifdarL homepage on the InternetWorlds Happiest Cities2013 From Rio de Janeiro to San Francisco. Available from: www.travelerstoday.comAccessed February 7, 2017

- GladmanDDLandewéRMcHughNJComposite measures in psoriatic arthritis: GRAPPA 2008J Rheumatol201037245346120147481

- Nell-DuxneunerVPStammTAMacholdKPPflugbeilSAletahaDSmolenJSEvaluation of the appropriateness of composite disease activity measures for assessment of psoriatic arthritisAnn Rheum Dis201069354654919762363

- GuptaMAGuptaAKThe Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory: a preliminary index of psoriasis-related stressActa Derm Venereol19957532402437653188

- SampognaFChrenMMMelchiCFAge, gender, quality of life and psychological distress in patients hospitalized with psoriasisBr J Dermatol2006154232533116433804

- JapiassuMACFAvaliação da Qualidade de Vida em Pacientes com Psoríase [Evaluation of quality of life in patients with psoriasis] [thesis]Rio de JaneiroUniversidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro2008

- TestaMASimonsonDCAssesment of quality-of-life outcomesN Engl J Med1996334138358408596551

- JayaprakasamADarvayAOsborneGMcGibbonDComparison of assessments of severity and quality of life in cutaneous diseaseClin Exp Dermatol200227430630812139677

- PollardLCChoyEHGonzalezJKhoshabaBScottDLFatigue in rheumatoid arthritis reflects pain, not disease activityRheumatology (Oxford)200645788588916449363

- Repping-WutsHFransenJvan AchterbergTBleijenbergGVan RielPPersistent severe fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Clin Nurs20071611C37738317931330

- van HoogmoedDFransenJBleijenbergGvan RielPPhysical and psychosocial correlates of severe fatigue in rheumatoid arthritisRheumatology (Oxford)20104971294130220353956

- SuurmeijerTPWatlzMMoumTQuality of life profiles in the first years of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the EURIDISS longitudinal studyArthritis Rheum200145211112111324773

- TreharneGJLyonsACHaleEDGoodchildCEBoothDAKitasGDPredictors of fatigue over 1 year among people with rheumatoid arthritisPsychol Health Med200813449450418825587

- De ArrudaLHDe MoraesAPThe impact of psoriasis on quality of lifeBr J Dermatol2001144suppl 58333611501512

- RappSRFeldmanSRExumMLFleischerABJrReboussinDMPsoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseasesJ Am Acad Dermatol1999413 pt 140140710459113

- WeissSCKimballABLiewehrDJBlauveltATurnerMLEmanuelEJQuantifying the harmful effect of psoriasis on health-related quality of lifeJ Am Acad Dermatol200247451251812271293

- HongJKooBKooJThe psychosocial and occupational impact of chronic skin diseaseDermatol Ther2008211545918318886

- HughesJEBarracloughBMHamblinLGWhiteJEPsychiatric symptoms in dermatology patientsBr J Psychiatry198314351546882992

- WesselySCLewisGHThe classification of psychiatric morbidity in attenders at a dermatology clinicBr J Psychiatry19891556866912611599

- Attah JohnsonFYMostaghimiHCo-morbidity between dermatologic diseases and psychiatric disorders in Papua New GuineaInt J Dermatol19953442442487790138

- AktanSOzmenESanliBPsychiatric disorders in patients attending a dermatology outpatient clinicDermatology199819732302349812026

- PicardiAAmerioPBalivaGRecognition of depressive and anxiety disorders in dermatological outpatientsActa Derm Venereol200484321321715202838

- PicardiAAbeniDRenziCBragaMMelchiCFPasquiniPTreatment outcome and incidence of psychiatric disorders in dermatological out-patientsJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol200317215515912705743

- MaginPAdamsJHeadingGPondDSmithWExperiences of appearance-related teasing and bullying in skin diseases and their psychological sequelae: results of a qualitative studyScand J Caring Sci200822343043618840226

- LopesCSFaersteinEChorDStressful life events and common mental disorders: results of the Pro-Saude StudyCad Saude Publica20031961713172014999337

- MinnockPKirwanJVealeDFitzgeraldOBresnihanBFatigue is an independent outcome measure and is sensitive to change in patients with psoriatic arthritisClin Exp Rheumatol201028340140420525443

- GladmanDDMeasePJCifaldiMAPerdokRJSassoEMedichJAdalimumab improves joint-related and skin-related functional impairment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: patient-reported outcomes of the Adalimumab Effectiveness in Psoriatic Arthritis TrialAnn Rheum Dis200766216316817046964