Abstract

An increasing number of people are getting tattoos; however, many regret the decision and seek their removal. Lasers are currently the most commonly used method for tattoo removal; however, treatment can be lengthy, costly, and sometimes ineffective, especially for certain colors. Ingenol mebutate is a licensed topical treatment for actinic keratoses. Here, we demonstrate that two applications of 0.1% ingenol mebutate can efficiently and consistently remove 2-week-old tattoos from SKH/hr hairless mice. Treatment was associated with relocation of tattoo microspheres from the dermis into the posttreatment eschar. The skin lesion resolved about 20 days after treatment initiation, with some cicatrix formation evident. The implications for using ingenol mebutate for tattoo removal in humans are discussed.

Keywords:

Introduction

Tattooing has increased in popularity in recent years among both women and men.Citation1,Citation2 In 2002, a Harris poll showed a tattoo prevalence of 16%, and in 2006, a North American survey found that 24% of 18–50-year olds had tattoos.Citation3 A survey of 16–64-year olds (n=8,656) in Australia found that 14.5% of respondents had a tattoo.Citation1 In the USA, ≈50,000 new tattoos are placed every year, and 24% of college students and 10% of adult males have been estimated to have tattoos.Citation4 Unfortunately, up to 20%–50% of wearers regret obtaining their tattoos,Citation4,Citation5 with one survey reporting that 28% of tattooed individuals regretted the decision within 1 month.Citation6 However, the percentage of individuals with tattoos who undergo tattoo removal treatment is reported to be around 6%–8%.Citation5,Citation7

Tattoo removal dates back to ancient Egyptian times, with ancient Greeks purporting to use inter alia, garlic mixed with cantharidin,Citation4 an acantholytic vesicant (with a number of traditional dermatological uses) that can be obtained from beetles in the family Meloidae.Citation8 Currently lasers, primarily Quality-switched lasers, are generally used for tattoo removalCitation9 and can, for instance, achieve up to 95% clearance of black and blue tattoos.Citation10,Citation11 Laser treatment is believed to result in both chemical cleavage of pigment and/or fragmentation the pigment particles,Citation2 with the fragments phagocytosed by the posttreatment inflammatory infiltrate. Subsequent local redistribution of fragments, and perhaps removal via the lymphatics, is believed to result in the tattoo becoming clinically inapparent.Citation10,Citation11 Laser treatments are typically spaced by 1–2 months, with the overall treatment course often prolonged and costly, requiring from 4 to more than 10 treatment sessions.Citation2 Tattoo removal can also be incomplete, with tattoos containing a mixture of different colors presenting a particular challenge.Citation2,Citation10,Citation11 However, picosecond laser technology continues to evolve, with new wavelength lasers improving the removal of difficult-to-remove colors.Citation10,Citation11

Ingenol mebutate is a topical therapeutic agent derived from the sap of Euphorbia peplusCitation12,Citation13 and is licensed for use in field-directed treatment of actinic keratosis, with treatment involving a daily application of 0.05% ingenol mebutate for 2 or 3 days.Citation14,Citation15 The treatment, by removing both actinic keratosis and surrounding mutated keratinocytes, seeks to reduce future risk of squamous cell carcinoma development.Citation16,Citation17 The drug (originally called PEP005) activates protein kinase C,Citation18 and the treatment is associated with a transient inflammatory response,Citation19 with a generally favorable cosmetic outcome in human studies.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 Studies in mice have shown that topical ingenol mebutate treatment results in 1) the loss of the epithelial layer within 1–2 days, with keratinocytes undergoing primary necrosisCitation13 (or possibly pyroptosisCitation22), 2) dermal hemorrhage,Citation22,Citation23 and 3) an acute inflammatory responseCitation17 involving a pronounced neutrophil infiltrate within 24 hours.Citation13,Citation24 This is followed by eschar formation and reepithelialization, which begins within 48 hours after treatment initiation.Citation17,Citation22 Here, we show that ingenol mebutate treatment of skin tattoos in SKH/hr hairless mice resulted in their complete removal. The dye-containing tattoo microspheres used herein were followed by histology and could clearly be seen to have relocated from the dermis into the posttreatment eschar.

Methods

Animal ethics statement

Mouse work was conducted in accordance with the “Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes” as defined by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The mouse work was approved by the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute’s animal ethics committee (P891). Mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide.

SKH1/hr mice

Outbred SKH1/hr mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, NC, USA), and a breeding colony for outbred SKH1/hr mice was established at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute.

Tattoo application and ingenol mebutate treatment

Mice were tattooed on their backs with one ≈1 cm × ≈1 cm cross using human-grade blue tattoo ink composed of a fluorescent dye encapsulated within polymethylmethacrylate microspheres (FireFly BMX1000, Marine Blue; Protat Tattoo Supplies, Adelaide, SA, Australia). The tattoos were applied using a Harvard Apparatus tattooing machine (Harvard Apparatus Ltd., Holliston, MA, USA). Two weeks later, the mice were randomly allocated into two groups, one received ingenol mebutate (0.1% in gel) and the other gel alone (placebo; both supplied by Peplin Ltd., Brisbane, QLD, Australia).Citation17 Treatments were applied topically (50 µL) to the tattoo, daily for 2 days. The gels were spread to ensure that the gel covered the entire tattoo. The gel contains isopropyl alcohol, hydroxyethylcellulose, citric acid monohydrate, sodium citrate, benzyl alcohol, and purified water.

Histology

Skin samples at the tattoo site were cut out with a scalpel and fixed in 10% formalin and processed for paraffin embedding at the indicated times after ingenol mebutate treatment. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse E800 fluorescent microscope and images taken with a Nikon DXM 1200F digital camera attachment (Nikon, Sydney, NSW, Australia). Slides were illuminated with normal bright light and UV light (DAPI setting).

Results

Tattoo removal with 0.1% ingenol mebutate

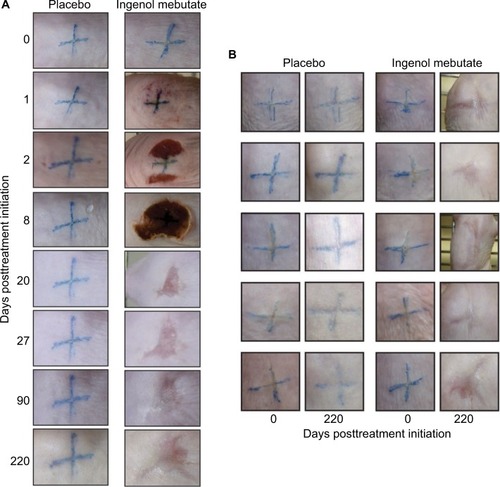

Tattooed crosses were placed on the backs of hairless SKH1/hr mice, and after 2 weeks, the tattooed areas (, Day 0) were treated once per day for 2 days with placebo gel or 0.1% ingenol mebutate gel. Two days after ingenol mebutate treatment initiation, an eschar began to form at the treatment site, which was fully formed by Day 8 (). Around Day 20, the eschar dropped off and no tattoo remained visible in the skin, with the site continuing to heal over the following weeks (). Placebo-treated tattoos showed no significant change over this period (). A cohort of five mice is shown to illustrate the consistency of the results obtained, with tattoos shown before treatment (Day 0) and 220 days after treatment (). Placebo treatment again had no significant effect (). Ingenol mebutate gel at 0.05% (a concentration used in humansCitation16) was also partially effective at tattoo removal in SKH/hr mice (data not shown).

Figure 1 Tattoo removal with ingenol mebutate.

Notes: (A) Photographs of two tattoos (≈1 cm × ≈1 cm blue crosses), one treated with placebo and the other with ingenol mebutate, and both followed over time (till Day 220). A fully formed eschar can be seen on Day 8 over the ingenol mebutate-treated tattoo site. (B) Pictures of five tattoos on five mice treated with placebo gel and five tattoos on another five mice treated with ingenol mebutate. Pictures were taken before treatment (Day 0) and 220 days after treatment.

The topical ingenol mebutate treatment used herein for tattoo removal showed similar changes in the skin of SKH1/hr mice to those reported previously when ingenol mebutate was used for field-directed treatment of skin lesions.Citation17,Citation25 Inflammation (erythema) was evident within a day, and eschar formation began on Day 2, with the skin recovering around Day 20 (). Ingenol mebutate treatment (as reported previously in these miceCitation17) resulted in some skin contraction (suggesting dermal disruption), with slightly darker pink irregular markings remaining within the treatment areas (, Day 220). Such changes are not seen in humans after ingenol mebutate treatment.Citation16,Citation20,Citation21

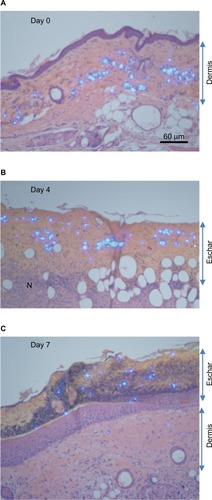

Histological examination of ingenol mebutate-treated tattoos

For the tattoos, a microsphere-based product was used, which contained a fluorescent dye that fluoresces under UV light. The light-blue colored tattoo microspheres could thus be clearly seen in hematoxylin and eosin sections illuminated with both white and UV light. The microspheres were clearly visible in the dermis prior to treatment (, dermis). After ingenol mebutate treatment, hemorrhage, mononuclear cell infiltrates (shown previously to be neutrophilsCitation13,Citation24), and loss of epidermis were apparent within 1–2 days, as described previously in these mice.Citation17 Importantly, by Day 4, the microspheres could be clearly seen located within the purulent exudate forming an eschar over the dermis (, eschar). A resolving mononuclear cell infiltrate could also be seen in the dermis (). By Day 7, the epithelium had fully reformed (slightly thickenedCitation26) and the eschar had darkened and crusted, with tattoo microspheres clearly located within the eschar (, eschar).

Figure 2 Histology of tattoo sites before and after ingenol mebutate treatment.

Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; UV, ultraviolet.

Discussion

Here, we show that 0.1% ingenol mebutate gel was able to remove efficiently and consistently 2-week-old tattoos from SKH/hr hairless mice. The mechanism of tattoo removal by ingenol mebutate appears to be quite distinct from that seen after laser treatment. The tattoo dye-containing microspheres remained intact and were exuded out of the dermis into an eschar, which then dropped off as the skin healed. This mechanism of action would suggest that tattoo removal facilitated by ingenol mebutate is likely to be independent of the tattoo ink color.

Ingenol mebutate treatment induces a complex series of changes in the skin, including epithelial and dermal disruption, hemorrhage, inflammation, and neutrophil infiltration, followed by eschar formation and ultimately some cicatrix formation ( and ).Citation17 Imiquimod, which like ingenol mebutate is used for treating actinic keratoses, was also reported similarly to be able to remove tattoos in a guinea pig model, with evident epidermal and dermal necrosis, hemorrhage, inflammation, neutrophil infiltration, and eschar formation.Citation27 Dermabrasion (to remove the epidermis) has also been used for tattoo removal, with tattoo pigment mobilized and extruded from the inflamed skin into a dressing covering the treatment site.Citation28,Citation29 Increased tattoo pigment phagocytosis has also been proposed as a mechanism for imiquimod and dermabrasion.Citation29,Citation30 However, ingenol mebutate activates PKC,Citation18 which is reported to suppress phagocytic activity of neutrophils.Citation31,Citation32 One might therefore speculate that the ingenol mebutate treatment-induced inflammatory response mobilized the tattoo microspheres via edema formation and degradation of the extracellular matrix,Citation33 with the microspheres (≈30 µm diameter) likely becoming encapsidated by connective tissue.Citation34 Purulent exudation, driven by tissue pressure (≈10 mmHg), may then carry the microspheres out of the skin into an eschar. A weakness of the current study is that no time series was undertaken; the efficacy of ingenol mebutate for removing older tattoos (potentially with more mature encapsidationCitation34) remains to be established.

Imiquimod has been reported to facilitate tattoo removal in conjunction with Quality-switched laser treatment in a guinea pig model.Citation35 Human studies have shown inconsistent results, with a study in 3 patients suggesting that imiquimod facilitated tattoo removal in conjunction with laser treatment,Citation30 whereas another study in 19 patients reported that imiquimod was ineffective in this setting.Citation36 Whether ingenol mebutate could synergize with laser treatment to facilitate tattoo removal in humans without cicatrix formation clearly remains to be tested, given that there are substantial differences between mouse and human skin.Citation37

Acknowledgments

S-J Cozzi was funded by an Industry Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia. A Suhrbier is a Principal Research Fellow of the NHMRC. The research was conducted at QIMR Berghofer with consumables and research staff funded by Peplin Ltd. We thank the histopathology and animal house staff of QIMRB for excellent support.

Disclosure

A Suhrbier was a paid consultant for Peplin Ltd. and LEO Pharma. S-J Cozzi was an employee of LEO Pharma. SM Ogbourne was an employee of Peplin Ltd. A Suhrbier and S-J Cozzi are named inventors on a patent (WO/2012/176015) held by LEO Pharma, but receive no royalties or other remuneration. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HeywoodWPatrickKSmithAMWho gets tattoos? Demographic and behavioral correlates of ever being tattooed in a representative sample of men and womenAnn Epidemiol2012221515622153289

- LauxPTralauTTentschertJA medical-toxicological view of tattooingLancet20163871001639540226211826

- UrdangMMallekJTMallonWKTattoos and piercings: a review for the emergency physicianWest J Emerg Med201112439339822224126

- AdattoMAHalachmiSLapidothMTattoo removalCurr Probl Dermatol2011429711021865802

- ArmstrongMLRobertsAEKochJRSaundersJCOwenDCAndersonRRMotivation for contemporary tattoo removal: a shift in identityArch Dermatol2008144787988418645139

- VarmaSLaniganSWReasons for requesting laser removal of unwanted tattoosBr J Dermatol1999140348348510233271

- HoughtonSJDurkinKParryETurbettYOdgersPAmateur tattooing practices and beliefs among high school adolescentsJ Adolesc Health19961964204258969374

- MoedLShwayderTAChangMWCantharidin revisited: a blistering defense of an ancient medicineArch Dermatol2001137101357136011594862

- HoSGGohCLLaser tattoo removal: a clinical updateJ Cutan Aesthetic Surg201581915

- BaumlerWLaser treatment of tattoos: basic principlesCurr Probl Dermatol2017529410428288450

- JakusJKailasAPicosecond lasers: a new and emerging therapy for skin of color, minocycline-induced pigmentation, and tattoo removalJ Clin Aesthet Dermatol201710141528360964

- RamsayJRSuhrbierAAylwardJHThe sap from Euphorbia peplus is effective against human nonmelanoma skin cancersBr J Dermatol2011164363363621375515

- OgbourneSMSuhrbierAJonesBAntitumor activity of 3-ingenyl angelate: plasma membrane and mitochondrial disruption and necrotic cell deathCancer Res20046482833283915087400

- AlchinDRIngenol mebutate: a succinct review of a succinct therapyDermatol Ther201442157164

- BermanBSafety and tolerability of ingenol mebutate in the treatment of actinic keratosisExpert Opin Drug Saf201514121969197826524598

- LebwohlMSwansonNAndersonLLMelgaardAXuZBermanBIngenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosisN Engl J Med2012366111010101922417254

- CozziSJOgbourneSMJamesCIngenol mebutate field-directed treatment of UVB-damaged skin reduces lesion formation and removes mutant p53 patchesJ Invest Dermatol201213241263127122189786

- KedeiNLundbergDJTothAWelburnPGarfieldSHBlumbergPMCharacterization of the interaction of ingenol 3-angelate with protein kinase CCancer Res20046493243325515126366

- ErlendssonAMKarmisholtKEHaakCSStenderIMHaedersdalMTopical corticosteroid has no influence on inflammation or efficacy after ingenol mebutate treatment of grade I to III actinic keratoses (AK): a randomized clinical trialJ Am Acad Dermatol201674470971526810403

- SillerGRosenRFreemanMWelburnPKatsamasJOgbourneSMPEP005 (ingenol mebutate) gel for the topical treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase IIa trialAustralas J Dermatol20105129910520546215

- LewohlMSohnAIngenol mebutate (ingenol 3-angelate, PEP005): focus on its uses in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancerExpert Opin Drug Saf201272121128

- LeTTSkakKSchroderKIL-1 contributes to the anti-cancer efficacy of ingenol mebutatePloS One2016114e015397527100888

- LiLShuklaSLeeAThe skin cancer chemotherapeutic agent ingenol-3-angelate (PEP005) is a substrate for the epidermal multidrug transporter (ABCB1) and targets tumor vasculatureCancer Res201070114509451920460505

- ChallacombeJMSuhrbierAParsonsPGNeutrophils are a key component of the antitumor efficacy of topical chemotherapy with ingenol-3-angelateJ Immunol2006177118123813217114487

- CozziSJLeTTOgbourneSMJamesCSuhrbierAEffective treatment of squamous cell carcinomas with ingenol mebutate gel in immunologically intact SKH1 miceArch Dermatol Res20133051798322871992

- SchroderWAAnrakuILeTTSerpinB2 deficiency results in a stratum corneum defect and increased sensitivity to topically applied inflammatory agentsAm J Path201618661511152327109612

- SolisRRDivenDGColome-GrimmerMISnyderNtWagnerRFJrExperimental nonsurgical tattoo removal in a guinea pig model with topical imiquimod and tretinoinDermatol Surg20022818386 discussion 86–8711998793

- ClabaughWATattoo removal by superficial dermabrasion. Five-year experiencePlast Reconstr Surg19755544014051118499

- ClabaughWRemoval of tattoos by superficial dermabrasionArch Dermatol19689855155215684226

- ElsaieMLNouriKVejjabhinantaVTopical imiquimod in conjunction with Nd:YAG laser for tattoo removalLasers Med Sci200924687187519597914

- DeChateletLRShirleyPSJohnstonRBJrEffect of phorbol myristate acetate on the oxidative metabolism of human polymorphonuclear leukocytesBlood19764745455541260119

- Wang-IversonPPryzwanskyKBSpitznagelJKCooneyMHBactericidal capacity of phorbol myristate acetate-treated human polymorphonuclear leukocytesInfect Immun1978223945955730386

- AlfakryHMalleEKoyaniCNPussinenPJSorsaTNeutrophil proteolytic activation cascades: a possible mechanistic link between chronic periodontitis and coronary heart diseaseInnate Immun2016221859926608308

- LemperleGMorhennVBPestonjamaspVGalloRLMigration studies and histology of injectable microspheres of different sizes in micePlast Reconstr Surg200411351380139015060350

- RamirezMMageeNDivenDTopical imiquimod as an adjuvant to laser removal of mature tattoos in an animal modelDermatol Surg200733331932517338690

- RicottiCAColacoSMShammaHNTrevinoJPalmerGHeaphyMRJrLaser-assisted tattoo removal with topical 5% imiquimod creamDermatol Surg20073391082109117760599

- SepehriMJorgensenBSerupJIntroduction of dermatome shaving as first line treatment of chronic tattoo reactionsJ Dermatolog Treat20152645145525672517