Abstract

Prurigo nodualris (PN) is a chronic condition with highly pruritic, hyperkeratotic papules or nodules arising in the setting of chronic pruritus. While PN may serve as a phenotypic presentation of several underlying conditions such as atopic dermatitis, chronic kidney disease-related pruritus, and neurological diseases, it represents a distinct clinical entity that may persist despite the removal of the underlying cause, if one is identified. Neuronal proliferation, eosinophils, mast cells, and small-fiber neuropathy play a role in the production of pruritus in PN, although the exact mechanism has not yet been established. Identifying an underlying cause, if present, is essential to prevent recurrence of PN. Due to often present comorbidities, treatment is typically multimodal with utilization of topical and systemic therapies. We performed a PubMed/MEDLINE search for PN and present a review of recent developments in the treatment of PN. Treatment typically relies on the use of topical or intralesional steroids, though more severe or recalcitrant cases often necessitate the use of phototherapy or systemic immunosuppressives. Thalidomide and lenalidomide can both be used in severe cases; however, their toxicity profile makes them less favorable. Opioid receptor antagonists and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists represent two novel families of therapeutic agents which may effectively treat PN with a lower toxicity profile than thalidomide or lenalidomide.

Introduction

PN is an intensely pruritic, chronic skin condition characterized by localized or generalized hyperkeratotic papules and nodules typically in a symmetrical distribution.Citation1 PN is accompanied by long-standing pruritus and thought to develop as a reaction to repeated scratching in patients with CP from various etiologies including dermatological, systemic, infectious, and psychiatric.Citation2–Citation4 Although most patients present with several associated conditions that may explain the development of CP, there is a significant percentage (~13%) who do not have an identifiable illness or predisposing condition that would serve as an initial trigger.Citation2 The initiation of an itch–scratch cycle perpetuates the development of PN and explains the propensity for symmetrical distribution of lesions and the characteristic absence on the upper mid back.Citation5 Lesions can number from several to hundreds, and can vary greatly in size.Citation4

Recent work on the pathogenesis of PN has pointed to a complex interplay of pro-inflammatory and pruritogenic substances in addition to increased local concentrations of neuropeptides in lesional skin that may be responsible for the alterations in nerve density and cutaneous inflammation found in PN.Citation6–Citation9 Despite these findings, our understanding of the pathophysiology remains unclear. In an effort to simplify terminology, it was recently proposed to utilize chronic prurigo as an all-encompassing clinical term for the various subtypes (nodular, papular, umbilicated) of prurigo based on the unifying core symptoms of CP (>6 weeks), signs of repeated scratching, and the development of pruriginous lesions.Citation10 Still, cases such as pemphigoid nodularis, where the underlying disease requires a significantly different treatment regimen, complicate utilization of such terminology.Citation11 As such, we will make distinctions between treating prurigo and addressing underlying causes of the prurigo.

Pruritus as a symptom is present in many diseases, and a certain subset of patients may be predisposed to a higher sensitivity or lower tolerance to pruritus, developing a clinical prurigo response under the influence of the itch–scratch cycle.Citation12 Resolution of the underlying etiology with eventual neuronal sensitization can ensue leading to perpetuation and spread of this secondary response.Citation13,Citation14 Although the evolution of this prurigo response is dependent on the underlying systemic illness inducing CP, chronic scratching itself appears to alter the environment in the dermis and epidermis as evidenced by increased levels of neuropeptides and neurohyperplasia.Citation8,Citation9,Citation15 This results in a chronic condition that may no longer be dependent on the underlying etiology that originally caused the CP.

In light of the difficulties in adequately categorizing PN, epidemiological and treatment studies are often limited to smaller, less-powered studies. We performed a PubMed/MEDLINE review of PN and herein review its etiology and various treatment options.

Epidemiology

Despite PN’s fairly frequent occurrence in the clinical setting, studies on the prevalence and incidence of PN have to date consisted of small case studies and case reports. To ascertain the incidence of PN, Pereira et al performed a survey study across 14 countries and demonstrated that 60% of respondents, on average, saw fewer than five PN patients per month presenting to clinic.Citation16 Overall, epidemiological studies are lacking.

A majority of patients with PN present between the ages of 51 and 65, though several cases in other age groups have been described, including pediatric patients.Citation2,Citation17–Citation19 Multiple groups have demonstrated that individuals with an atopic predisposition have an earlier age of onset.Citation2,Citation20,Citation21 More recently, the largest study to investigate the demographics and comorbidities associated with PN determined that African Americans are 3.4 times more likely to have PN than white patients.Citation19 In that same study, significant novel associations with a variety of systemic diseases including COPD, and heart failure were found.Citation19

Clinical presentation

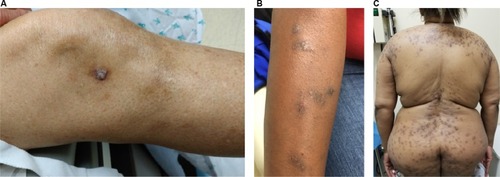

PN is a chronic condition defined by the presence of highly pruritic, hyperkeratotic papules or nodules arising in the setting of CP and the induction of an uncontrollable itch– scratch cycle. Repeated scratching can lead to excoriation, further lichenification, or crusting, often resulting in a hyperpigmented border secondary to the inflammatory stimulus (). Lesions are distributed in areas accessible to chronic scratching and are often found in a symmetrical distribution over the extensor surfaces, trunk, and lower extremities.Citation5,Citation22 PN can also be localized in the setting of an underlying local dermatosis such as venous stasis, postherpetic neuralgia, or brachioradial pruritus.Citation4,Citation14,Citation23 Regardless of the distribution, PN is thought to harbor the highest itch intensity among the most frequent causes of CP.Citation2,Citation12 Patients experience a combination of pruritic sensations including burning, stinging, and alterations in lesional temperature.Citation2 These varying sensations and the underlying etiology do not, however, appear to affect the severity or course of PN.Citation10

PN has a significant effect on the quality of life which can lead to psychological distress, and sleep disturbances.Citation24,Citation25 There is a significant association between PN, depression, and increased anxiolytic and antidepressant use further underscoring the biopsychosocial nature of this condition.Citation26,Citation27

Pathology and dermoscopy

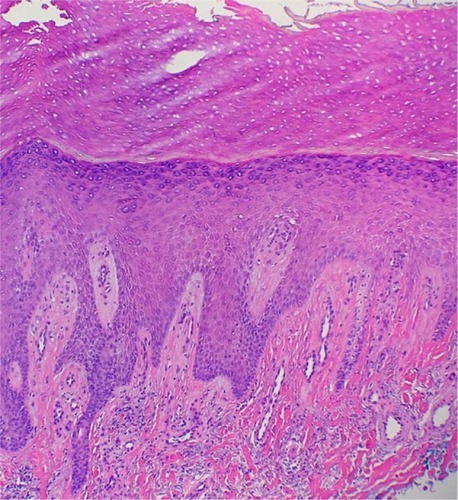

Histological features of PN have been characterized by Weigelt et al upon assessment of 136 histological samples. The most frequent epidermal features included compact orthohyperkeratosis (84%), irregular elongation of the rete ridges (58%), and focal or broad hypergranulosis (52.2%). Dermal changes consisted of fibrosis of the papillary dermis (71.3%) with vertical arrangement of collagen fibers (64%), and an increased number of capillaries (65.4%) (). An inflammatory infiltrate was present in virtually all the patients; most of it was composed by lymphocytes and histiocytes. However, half of the specimens showed eosinophils and neutrophils as well.Citation28 Dermatoscopic features described in small series consisted of white areas with peripheral striations, hyperkeratosis and scaling, crusts, erosions and follicular plugging, red dots, and red globules.Citation29,Citation30

Underlying conditions

Dermatological diseases

Several dermatoses have established associations with PN, all of which have a documented high level of pruritic intensity which typically precedes the development of pruriginous lesions through the evolution of an itch–scratch cycle and neuronal sensitization.Citation2,Citation12 The most documented and well studied is the association between PN and an atopy.Citation2 Atopic prurigo may be the dominant manifestation of atopic dermatitis and is more commonly seen in children.Citation31

Additional underlying dermatoses that generate pruriginous lesions include venous stasis dermatitis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and mycosis fungoides.Citation4,Citation32,Citation33 Aside from underlying dermatological diseases, infectious etiologies limited to the skin may also predispose a patient to chronic itching and initiate a prurigo response. Patients with lesions typical of PN have in rare cases been found to harbor various species of mycobacteria, exhibiting favorable responses with initiation of antituberculosis therapy.Citation34,Citation35

Systemic and neurological diseases

Systemic diseases with an intense pruritic manifestation can lead to the development of PN. HIV may initially present with pruritus, and patients are known to develop an intractable itch with disease progression.36−38 PN lesions in HIV patients correlate with depleted CD4 counts.Citation39 Recently, in a large study at a single academic institution, black patients with PN were 8.5−10 times more likely to have HIV than race-matched controls with atopic dermatitis or psoriasis.Citation19 Because of PN’s association with an advanced state of immunosuppression, and improvement of PN symptoms with initiation of therapy, it is suggested for patients to undergo HIV testing.Citation19,Citation39

Between 25% and 42% of patients receiving hemodialysis experience CKD-ap.Citation40,Citation41 In another study investigating the dermatological findings associated with CKD-ap, 10% of patients presented with excoriations and scratched nodules consistent clinically with PN.Citation42 Overwhelmingly, the most common skin finding in patients receiving hemodialysis was xerosis cutis.Citation42 In a recent study, 60% of female patients with PN had concomitant xerosis cutis, 66% of which was from a nonatopic underlying condition.Citation43 These patients were more likely to see PN development at a later age and to have multiple underlying conditions associated with PN.Citation43 The most common diseases associated with this rare PN subtype were chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus.Citation44

Lesions characteristic of an acquired reactive perforating dermatosis observed in patients with underlying metabolic diseases are histologically representative of PN.Citation45,Citation46 There are case reports showing associations between a variety of malignancies47−49 including lymphoproliferative disorders, such as Sèzary syndrome, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and polycythemia vera.50−52

Neurological diseases causing damage to peripheral nerves through pathological compression, or through an SFN, have been associated with PN.Citation53 The herpes zoster virus damages small cutaneous nerve fibers and has been posited to serve as a trigger for development of postherpetic neuralgia and PN.Citation54 Pathological compression of nerves seen in brachioradial pruritus, and notalgia paresthetica with a resulting neuropathic itch may also produce PN lesions in a dermatomal distribution.Citation14,Citation23,Citation53,Citation55

Pathophysiology

Following the initial discovery of dermal neural hyperplasia in prurigo nodules by Pautrier in 1934, the role of cutaneous nerves has been repeatedly investigated.Citation56 Although dermal neuronal hyperplasia has been disputed by recent studies which demonstrated that increased nerve fiber density is not seen in the majority of patients, neuronal plasticity still appears to play a significant part in the development of PN.Citation4,Citation28,Citation57,Citation58

Prurigo nodules have higher concentrations of PGP 9.5, p75 NGFr, and CGRP nerve fibers in the upper dermis when compared to healthy skin.6,8,59−61 NGF, which binds to NGFr, is a neurotrophin that is necessary for the development and survival of neurons.Citation62–Citation64 In the skin, NGF is secreted by keratinocytes, mast cells, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes.Citation65–Citation71 Using NGF and p75 NGFr double-staining, Johansson et al found an increase in high-and low-affinity NGFr in dermal nerve fibers, and an increased production of NGF in dermally infiltrating inflammatory cells.Citation8 Additionally, NGF-producing eosinophils and mast cells were found in close proximity to NGFr-positive nerve fibers, suggesting a potential function for these inflammatory cells in promoting dermal neuronal hyperplasia in PN.Citation6,Citation7 Epidermal hyperplasia may also be explained by an increase in NGF given that NGF has been shown to induce keratinocyte proliferation in a dose-dependent manner.Citation66,Citation72,Citation73 NGF additionally has various biologic effects on the activity of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils, which is consistent with the finding that NGF promotes the production of SP by sensory neurons and histamine expression and release by mast cells.Citation67,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74–Citation76

SP, a tachykinin which binds to the NK1r, induces erythema, edema, vascular dilatation, plasma protein extravasation, and pruritus in cutaneous tissues.Citation77–Citation79 Increased density of SP-positive nerve fibers in PN lesions may promote inflammation and pruritus in PN.Citation9 This is supported by the finding that aprepitant, an anti-neurokinin-1 antagonist, and topical capsaicin, which depletes SP, reduce pruritus and the size of PN lesions.Citation80,Citation81 Histamine, a potent pruritogen, appears to play a role in the pruritus of PN as increased numbers of histamine-containing mast cells are found to be near NGFr-positive nerve fibers in the dermis of PN.Citation82,Citation83 Increased quantities of eosinophils containing eosinophilic cationic protein and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin are similarly found to be in close proximity to PGP 9.5-positive nerve fibers and with an increased density of granular proteins.Citation7 Furthermore, IL-31, a cytokine and pruritogen produced by eosinophils, has a 50-fold increased mRNA expression in PN biopsies when compared with healthy skin likely contributing to the pruritus in PN.Citation84,Citation85 Together, these pruritogens are believed to result in the intractable pruritus felt by patients with PN. Recently, PGP 9.5-positive IENFs were found to be reduced in PN and between lesions, with the restoration of the neuronal density in healed nodules, thus implicating the epidermis in pruritus.Citation15,Citation86

SFN has been proposed as a possible etiology for the itch associated with prurigo nodules.Citation15 SFNs involving αδ fibers and c fibers in the epidermis are characterized by IENF hypoplasia and are commonly associated with sensations of pruritus, burning, stinging, and prickling, symptoms which are frequently reported by patients with PN.Citation2,Citation15,Citation86–Citation90 In addition, patients who are treated with medications which are commonly used for the treatment of neuropathy, such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and capsaicin, show significant improvement of pruritus and severity of nodules.81,91−96 However, a small study of 12 patients using quantitative sensory testing, a measure of SFN, did not find a significant difference between PN and control skin.Citation97,Citation98

IL-6 and serotonin have also been hypothesized to act as a link between psychiatric disease and PN. IL-6 levels and serum serotonin levels – directly and indirectly, respectively – correlate with increased severity of pruritus suggesting a possible common pathway for the development of PN and depression.Citation99

Treatment of PN

The treatment of PN presents a challenge to the clinician as there are few RCTs delineating therapy options. Therapies should be tailored to the patient’s age, comorbidities, severity of PN, quality of life, and expected side effects.Citation100 Discussions with the patient should include advantages and disadvantages of the therapy, side effects, and possible use of off-label medications. Patient education can thus promote treatment adherence. Potential length of therapy should also be dis-cussed as PN is difficult to treat and patients may become frustrated with lack of improvement. Multimodal therapies which include both topical and systemic therapies may need to be implemented to achieve the goals of therapy – pruritic relief and healing of PN lesions. The addition of emollients is also recommended as a base therapy.

Identifying an underlying cause, if present, is essential to properly treating a patient with PN to prevent any recurrent pruritus that may lead to recurrence, as well as to avoid any treatments which may be contraindicated. We reported a patient who had received PUVA empirically for treatment of clinically diagnosed PN.Citation11 After several treatments, the patient developed a bullous eruption with workup confirming a diagnosis of pemphigoid nodularis, a variant of bullous pemphigoid. Thus, treatment for PN is not necessarily universal, and depends on addressing underlying dermatoses, if present. Herein, we discuss PN treatments in the case of recalcitrant PN lesions or adequate treatment of any identifiable underlying causes.

Topical and intralesional therapy

Direct injection of triamcinolone acetonide into PN lesions has produced clinical improvement and is often required for thicker lesions into which topical therapy cannot adequately penetrate.Citation101 These intralesional injections can be accompanied with cryotherapy.Citation102,Citation103 Likewise, high-potency topical corticosteroids can be used, due to their immunosuppressive effect on T-cells and cytokines implicated in the generation of pro-inflammatory and pruritogenic neuropeptides SP and CGRP.Citation6,Citation104,Citation105

The efficacy of less potent steroids, pimecrolimus, and calcipotriol has been investigated in RCT. Betamethasone valerate 0.1%-impregnated occlusive tape significantly decreased itch compared with an antipruritic moisturizing cream containing feverfew, a traditional medicinal herb.Citation105

Topical calcineurin inhibitors have strong antipruritic effects stemming from their immunomodulatory role in cytokine release and inhibition of the TRPV1 receptor which stimulates neurogenic inflammation.Citation106,Citation107 In a randomized, controlled, double-blind study, Siepmann et al compared the efficacy of 0.1% pimecrolimus cream to 0.1% hydrocortisone cream applied twice daily over 8 weeks in 30 nonatopic PN patients.Citation107 There was a significant reduction in itch, assessed by the VAS, with 2.7 points for pimecrolimus and 2.8 for hydrocortisone.Citation107 This effect could be observed 10 days after initiation of therapy. Comparatively, however, there was not a significant difference in reduction of scratch lesions, serum neuropeptide levels, or itch between the two treatment arms.Citation107 Pimecrolimus was as effective as hydrocortisone and offers an alternative topical treatment that may be implemented in a long-term regimen.Citation107

Calcipotriol ointment, a synthetic form of vitamin D, was compared to betamethasone valerate 0.1% ointment in a small RCT, with calcipotriol ointment showing greater efficacy and more rapid clearance of prurigo lesions.Citation108

Antihistamines and leukotriene inhibitors

Antihistamines are utilized in PN therapy given an increased number of mast cells detected in PN lesions.Citation83 High-dose nonsedating antihistamine for daytime followed by sedating antihistamine during night has exhibited beneficial effects in patients with CP in a case series.Citation109 Combination therapy of fexofenadine and montelukast improved lesions and pruritus in 11 of 15 patients with both PN and pemphigoid nodularis. One patient achieved remission with this regimen.Citation110 Currently, there are insufficient data from RCTs on the use of antihistamines for PN.

Phototherapy/excimer

Phototherapy can be utilized for the treatment of various inflammatory skin conditions and is a therapeutic alternative for patients with multiple comorbidities or generalized PN. UV-light exposure provides an anti-inflammatory effect and can decrease itch in inflammatory skin disorders including atopic dermatitis and PN.Citation111 UVB radiation decreases the levels of NGF and CGRP, and has immunosuppressive effects which may decrease the levels of IL-31.Citation112,Citation113

Narrowband UVB results in a significant improvement in PN at an average dose of 23.88±26.00 J/cm2.Citation114 The combination therapy of narrowband 308 nm UVB and PUVA accelerated healing of PN lesions when compared with PUVA alone.Citation111 UVA monotherapy demonstrated improvement of PN nodules in a case series of 19 patients. Totally, 23 UVA phototherapy sessions were provided. Among the patients, 79% experienced at least slight improvement of their lesions and two patients achieved complete remission.Citation115 Excimer laser proved more beneficial than topical Clobetasol.Citation104

Modified Goeckerman therapy, which consists of daily multistep broadband UVB therapy followed by occlusive coal tar and topical steroid application, improved prurigo nodules in a case series.Citation116 Logistical consideration and potential carcinogenicity of coal tar limits utilization of this protocol.Citation117

Oral immunosuppressants

Oral immunosuppressive therapy should be considered for patients with severe, recalcitrant PN. A single-institution retrospective study demonstrated clinical improvement with fewer lesions and decreased pruritus using cyclosporine in an average time of 3 weeks at a mean dose of 3.1 mg/kg.Citation118 In this small study consisting of eight patients, six showed complete remission with no recurrence following treatment cessation.Citation118

There have been two retrospective studies investigating MTX use in difficult-to-treat PN. The initial small study showed remission or marked improvement with resolution of >50% of nodules in 76% of patients on a weekly 7.5−20 mg subcutaneous injection of MTX.Citation119 Conclusions, however, were limited by the continuation of various adjuvant treatments during MTX use. More recently, a multicenter report of 39 patients receiving 5−25 mg MTX weekly demonstrated a mean objective efficacy, defined as achieving complete or partial remission, of 2.4 months.Citation120 Cases were limited to PN refractory to conventional therapies and showed a mean duration of response of 19 months. With a median 16-month follow-up, 64% of patients were still well controlled but the majority required weekly maintenance MTX of 5–20 mg.Citation120 A significant proportion, 38%, experienced adverse effects attributable to MTX including nausea, gastrointestinal symptoms, and transaminitis.Citation120

Treatment with azathioprine and cyclophosphamide has also been reported to be successful.Citation121,Citation122 Oral tacrolimus therapy dramatically reduced pruritus in a patient who was previously treated with cyclosporine for PN.Citation123 Lastly, a combination therapy of three cycles of intravenous immunoglobulin followed by MTX and topical steroids had antipruritic effect on PN related to atopic dermatitis in a case study.Citation124

Novel treatments

Thalidomide and lenalidomide

Thalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent, which also acts as a central and peripheral depressant, and exhibits anti-inflammatory properties as a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor.Citation125 It has been used in dermatological diseases refractory to traditional therapies.Citation126 The therapeutic action against PN is thought to derive from its neurotoxic effects.Citation126 To date, the largest study investigating thalidomide use in refractory PN included 42 patients treated with an average of 100 mg of thalidomide for 105 weeks.Citation127 Each patient had prior treatments that proved insufficient, or began to suffer from adverse effects.Citation127 Efficacious treatment was observed in 32 patients, with one experiencing complete clearing.Citation127 Termination of therapy was most commonly due to adverse side effects with 59% of patients experiencing peripheral neuropathy.Citation127

A meta-analysis of over 280 patients with refractory CP treated with thalidomide described improvement of itch secondary to a variety of etiologies, most commonly PN.Citation125 Lenalidomide, a more potent molecular form of thalidomide, has a lower frequency of peripheral neuropathy and has demonstrated efficacy with decreased PN lesions and pruritus in a case series.Citation128,Citation129 However, despite the success of these therapies, significant side effects including teratogenicity, fatigue, neuropathy, and hypercoagulability relegate their use to severe and recalcitrant cases.Citation128,Citation130

Opioid receptor antagonists

Systemic µ-opioid receptor antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, are utilized in the treatment of pruritus associated with several systemic and dermatological diseases, including PN.Citation131,Citation132 The antipruritic effect is exerted through inhibition of µ-opioid receptors on nociceptive neurons and interneurons resulting in suppression of itch.Citation131 In this case series, 67.7% of patients with PN noted improvement of symptoms and 38% reported complete remission of PN.Citation131 Although gastrointestinal and neurological side effects are commonly observed with naltrexone use, they are generally limited to the initial 2 weeks of use.Citation132 Contraindications include use of active opiate, use of opioid containing medications, and significant liver disease.Citation132,Citation133 Currently, a clinical trial (NCT02174419) is conducting an ongoing investigation on the therapeutic benefits of nalbuphine for the treatment of PN. Nalbuphine is a dual µ-opioid receptor antagonist and κ-agonist (NCT02174419). Intranasal Butorphanol, also a dual µ-opioid receptor antagonist and κ-agonist, has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of intractable pruritus in a case series.Citation133

NK1r antagonists

SP, a tachykinin with strong affinity for NK1r found in the skin and central nervous system, has been implicated in stimulating pro-inflammatory and pruritogenic pathways involved in the induction and maintenance of itch.Citation134,Citation135 NK1r antagonists, aprepitant and serlopitant, could prevent SP-mediated signaling in the pathogenesis of PN.Citation9 Significant relief of itch was achieved in PN patients on aprepitant monotherapy.Citation80 The most significant response rate was among those with PN.Citation80 Histologically, PN lesions display an increased density of SP-positive nerve fibers which may explain the high response rates seen with NK1r antagonist therapy. This was followed up by Ohanyan et al who investigated the efficacy of topical aprepitant 1% gel compared to a placebo vehicle in a study with 19 patients.Citation136 Significantly elevated serum SP levels and increased NK1r expression were shown in PN patients when compared to controls.Citation136 The difference in the reduction of mean VAS score between the placebo (66%) and the topical aprepitant group (58%) was not significant indicating poor efficacy of topical NK1r antagonists.Citation136 Ständer et al compared the effects of daily 5 mg serlopitant to placebo for 8 weeks in 127 PN patients. Findings revealed significant reduction in VAS score in the serlopitant group (3.6 cm) compared to the placebo group (1.9 cm).Citation137

IL-31 receptor antibody

IL-31 is considered to play a bridging role between itch induction and maintenance of inflammation in pruritic skin disorders.Citation138,Citation139 Immunotherapy targeting the IL-31 pathway and halting the release of inflammatory cytokines may prove fruitful. Nemolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody to the IL-31 receptor A, found on dorsal root ganglion neurons, provided significant improvement in pruritus scores among patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.Citation140 However, its role in PN remains unclear.

Conclusion

PN is a chronic condition, typically preceded by an underlying cause of pruritis. PN is a distinct entity from these underlying causes and can persist despite resolution of the predisposing condition. Current pathogenesis indicates that neuronal sensitization and local changes in factor concentrations in the cutaneous microenvironment lead to PN. While treating the underlying factors of PN has an important role in preventing recurrence, the treatment of PN is distinct. Treatment typically relies on the use of topical or intralesional steroids, though more severe or recalcitrant cases often necessitate the use of phototherapy or systemic immunosuppressives. Thalidomide and lenalidomide can both be used in severe cases; however, their toxicity profile makes them less favorable. Opioid receptor antagonists and NK1r antagonists represent two novel families of therapeutic agents which may effectively treat PN with a lower toxicity profile than thalidomide or lenalidomide.

Abbreviations

| CKD-ap | = | chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus |

| CP | = | chronic pruritus |

| IENF | = | intraepidermal nerve fiber |

| MTX | = | methotrexate |

| NGF | = | nerve growth factor |

| NGFr | = | nerve growth factor receptor |

| NK1r | = | neurokinin 1 receptor |

| PGP | = | protein gene product |

| PN | = | prurigo nodularis |

| PUVA | = | psoralen ultraviolet A |

| RCT | = | randomized controlled trial |

| SFN | = | small-fiber neuropathy |

| SP | = | substance P |

| UVB | = | ultraviolet B |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ZeidlerCStänderSThe pathogenesis of Prurigo nodularis--’Super-Itch’ in explorationEur J Pain2016201374026416433

- IkingAGrundmannSChatzigeorgakidisEPhanNQKleinDStänderSPrurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patientsJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201327555055722364653

- WinhovenSMGawkrodgerDJNodular prurigo: metabolic diseases are a common associationClin Exp Dermatol200732222422517137473

- Rowland PayneCMWilkinsonJDMckeePHJureckaWBlackMMNodular prurigo – a clinicopathological study of 46 patientsBr J Dermatol198511344314394063179

- VaidyaDCSchwartzRAPrurigo nodularis: a benign dermatosis derived from a persistent pruritusActa Dermatovenerol Croat2008161384418358109

- LiangYJacobiHHReimertCMHaak-FrendschoMMarcussonJAJohanssonOCGRP-immunoreactive nerves in prurigo nodularis--an exploration of neurogenic inflammationJ Cutan Pathol200027735936610917163

- JohanssonOLiangYMarcussonJAReimertCMEosinophil cationic protein-and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin/eosinophil protein X-immunoreactive eosinophils in prurigo nodularisArch Dermatol Res2000292837137810994770

- JohanssonOLiangYEmtestamLIncreased nerve growth factor-and tyrosine kinase A-like immunoreactivities in prurigo nodularis skin -- an exploration of the cause of neurohyperplasiaArch Dermatol Res20022931261461911875644

- HaasSCapellinoSPhanNQLow density of sympathetic nerve fibers relative to substance P-positive nerve fibers in lesional skin of chronic pruritus and prurigo nodularisJ Dermatol Sci201058319319720417061

- PereiraMPSteinkeSZeidlerCEuropean Academy of dermatology and venereology European prurigo project: expert consensus on the definition, classification and terminology of chronic prurigoJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol20183271059106528857299

- AmberKTKortaDZde FeraudySGrandoSAVesiculobullous eruption in a patient receiving psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment for prurigo nodules: a case of PUVA-aggravated pemphigoid nodularisClin Exp Dermatol201742783383528597976

- MollanazarNKSethiMRodriguezRVRetrospective analysis of data from an itch center: integrating validated tools in the electronic health recordJ Am Acad Dermatol201675484284427646746

- BharatiAWilsonNJPeripheral neuropathy associated with nodular prurigoClin Exp Dermatol2007321677017034423

- YosipovitchGSamuelLSNeuropathic and psychogenic itchDermatol Ther2008211324118318883

- SchuhknechtBMarziniakMWisselAReduced intraepidermal nerve fibre density in lesional and nonlesional prurigo nodularis skin as a potential sign of subclinical cutaneous neuropathyBr J Dermatol20111651859121410670

- PereiraMPBastaSMooreJStänderSPrurigo nodularis: a physician survey to evaluate current perceptions of its classification, clinical experience and unmet needJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol2018

- AmerAFischerHPrurigo nodularis in a 9-year-old girlClin Pediatr20094819395

- VachiramonVTeyHLThompsonAEYosipovitchGAtopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common diseasePediatr Dermatol201229439540222471955

- BoozalisETangOPatelSEthnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patientsJ Am Acad Dermatol2018794714719.e71329733939

- TanakaMAibaSMatsumuraNAoyamaHTagamiHPrurigo nodularis consists of two distinct forms: early-onset atopic and lateonset non-atopicDermatology199519042692767655104

- TanWSTeyHLExtensive prurigo nodularis: characterization and etiologyDermatology2014228327628024662043

- ADRivetJMoulonguetIAtypical presentation of adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma due to HTLV-1: prurigo nodularis lasting twelve years followed by an acute micropapular eruptionActa Derm Venereol201090328729020526548

- PereiraMPLülingHDieckhöferASteinkeSZeidlerCStänderSBrachioradial pruritus and Notalgia paraesthetica: a comparative observational study of clinical presentation and morphological pathologiesActa Derm Venereol2018981828828902951

- WeisshaarESzepietowskiJCDarsowUEuropean guideline on chronic pruritusActa Derm Venereol201292556358122790094

- TessariGDalle VedoveCLoschiavoCThe impact of pruritus on the quality of life of patients undergoing dialysis: a single centre cohort studyJ Nephrol200922224124819384842

- JørgensenKMEgebergAGislasonGHSkovLThyssenJPAnxiety, depression and suicide in patients with prurigo nodularisJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol2017312e106e10727505149

- DazziCErmaDPiccinnoRVeraldiSCaccialanzaMPsychological factors involved in prurigo nodularis: a pilot studyJ Dermatolog Treat201122421121420666670

- WeigeltNMetzeDStänderSPrurigo nodularis: systematic analysis of 58 histological criteria in 136 patientsJ Cutan Pathol201037557858620002240

- BsABeergouderSLHypertrophic lichen planus versus prurigo nodularis: a dermoscopic perspectiveDermatol Pract Concept201662915

- ErrichettiEPiccirilloAStincoGDermoscopy of Prurigo nodularisJ Dermatol201542663263425808786

- PugliarelloSCozziAGisondiPGirolomoniGPhenotypes of atopic dermatitisJ Dtsch Dermatol Ges201191122021054785

- FurukitaKAnsaiSHidaYKuboYAraseSHashimotoTA case of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with unusual clinical featuresClin Exp Dermatol2009348e702e70419817767

- Jerković GulinSČeovićRLončarićDIlićIRadmanINodular Prurigo Associated with Mycosis Fungoides Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients Case ReportActa Dermatovenerol Croat201523320320726476905

- MattilaJOVornanenMVaaraJKatilaMLMycobacteria in prurigo nodularis: the cause or a consequence?J Am Acad Dermatol1996342 Pt 12242288642086

- SaporitoLFlorenaAMColombaCPampinellaDdi CarloPPrurigo nodularis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosisJ Med Microbiol200958Pt 121649165119661207

- SinghFRudikoffDHIV-associated pruritus: etiology and managementAm J Clin Dermatol20034317718812627993

- TarikciNKocatürkEGüngörŞuleOğuz TopalIÜlkümen CanPSingerRPruritus in systemic diseases: a review of etiological factors and new treatment modalitiesScientificWorldJournal20152015218

- MilazzoFPiconiSTrabattoniDIntractable pruritus in HIV infection: immunologic characterizationAllergy199954326627210321563

- MagandFNacherMCazorlaCCambazardFMarieDSCouppiéPPredictive values of Prurigo nodularis and herpes zoster for HIV infection and immunosuppression requiring HAART in French GuianaTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg2011105740140421621233

- PisoniRLWikströmBElderSJPruritus in haemodialysis patients: international results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS)Nephrol Dial Transplant200621123495350516968725

- WeissMMettangTTschulenaUPasslick-DeetjenJWeisshaarEPrevalence of chronic itch and associated factors in haemodialysis patients: a representative cross-sectional studyActa Derm Venereol201595781682125740325

- HayaniKWeissMWeisshaarEClinical findings and provision of care in haemodialysis patients with chronic itch: new results from the German epidemiological haemodialysis itch studyActa Derm Venereol201696336136626551638

- AkarsuSOzbagcivanOIlknurTSemizFInciBBFetilEXerosis cutis and associated co-factors in women with prurigo nodularisAn Bras Dermatol201893567167930156616

- KestnerRIStänderSOsadaNZieglerDMetzeDAcquired reactive perforating dermatosis is a variant of Prurigo nodularisActa Derm Venereol201797224925427349279

- WhiteCRHeskelNSPokornyDJPerforating folliculitis of hemodialysisAm J Dermatopathol1982421091167103012

- HurwitzRMMeltonMECreechFTWeissJHandtAPerforating folliculitis in association with hemodialysisAm J Dermatopathol1982421011087103011

- KhaledASfiaMFazaaBPrurigo chronique rélévant un lymphome T angioimmunoblastique [Chronic prurigo revealing an angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma]Tunis Med2009878534537 French20180359

- FunakiMOhnoTDekioSPrurigo nodularis associated with advanced gastric cancer: report of a caseJ Dermatol199623107037078973036

- LinJTWangWHYenCCYuITChenPMPrurigo nodularis as initial presentation of metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the bladderJ Urol2002168263163212131324

- DumontSPéchèreMToutous TrelluLChronic prurigo: an unusual presentation of Hodgkin lymphomaCase Rep Dermatol201810212212629928200

- ShelnitzLSPallerASHodgkin’s disease manifesting as prurigo nodularisPediatr Dermatol1990721361392359730

- SeshadriPRajanSJGeorgeIAGeorgeRA sinister itch: prurigo nodularis in Hodgkin lymphomaJ Assoc Physicians India20095771571620329432

- ASStänderSNeuropathic itch: diagnosis and managementDermatol Ther201326210410923551367

- DeDDograSKanwarAJPrurigo nodularis in healed herpes zoster scar: an isotopic responseJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol200721571171217448007

- MirzoyevSADavisMDBrachioradial pruritus: mayo Clinic experience over the past decadeBr J Dermatol201316951007101523796379

- PautrierLMA propos de la maladie de besnier-boeck-schaumann a forme de prurigo [Besnier-Boeck-Schaumann’s disease of prurigo type]Ann Dermatol Syphiligr1954815481490 French

- HarrisBHarrisKPenneysNSDemonstration by S-100 protein staining of increased numbers of nerves in the papillary dermis of patients with prurigo nodularisJ Am Acad Dermatol199226156581732336

- LindleyRPPayneCMNeural hyperplasia is not a diagnostic prerequisite in nodular prurigo. A controlled morphometric microscopic study of 26 biopsy specimensJ Cutan Pathol198916114182921380

- LiangYHeilbornJMarcussonJJohanssonOIncreased NGFR immunoreactive, dermal nerve fibers in prurigo nodularisEur J Dermatol19966563

- LiangYMarcussonJAJohanssonOLight and electron microscopic immunohistochemical observations of p75 nerve growth factor receptor-immunoreactive dermal nerves in prurigo nodularisArch Dermatol Res19992911142110025723

- Abadía MolinaFBurrowsNPJonesRRTerenghiGPolakJMIncreased sensory neuropeptides in nodular prurigo: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysisBr J Dermatol199212743443511419754

- JohnsonEMGorinPDBrandeisLDPearsonJDorsal root ganglion neurons are destroyed by exposure in utero to maternal antibody to nerve growth factorScience198021044729169187192014

- GoedertMOttenUHuntSPBiochemical and anatomical effects of antibodies against nerve growth factor on developing rat sensory gangliaProc Natl Acad Sci USA1984815158015846608728

- MobleyWCWooJEEdwardsRHDevelopmental regulation of nerve growth factor and its receptor in the rat caudate-putamenNeuron1989356556642561975

- di MarcoEMarchisioPCBondanzaSFranziATCanceddaRde LucaMGrowth-regulated synthesis and secretion of biologically active nerve growth factor by human keratinocytesJ Biol Chem19912663221718217221718982

- PincelliCSevignaniCManfrediniRExpression and function of nerve growth factor and nerve growth factor receptor on cultured keratinocytesJ Invest Dermatol1994103113188027574

- GronebergDASerowkaFPeckenschneiderNGene expression and regulation of nerve growth factor in atopic dermatitis mast cells and the human mast cell LINE-1J Neuroimmunol20051611–2879215748947

- KobayashiHGleichGJButterfieldJHKitaHHuman eosinophils produce neurotrophins and secrete nerve growth factor on immunologic stimuliBlood20029962214222011877300

- SolomonAAloeLPe’erJNerve growth factor is preformed in and activates human peripheral blood eosinophilsJ Allergy Clin Immunol199810234544609768588

- NilssonGForsberg-NilssonKXiangZHallböökFNilssonKMetcalfeDDHuman mast cells express functional TrkA and are a source of nerve growth factorEur J Immunol1997279229523019341772

- LambiaseABracci-LaudieroLBoniniSHuman CD4+ T cell clones produce and release nerve growth factor and express high-affinity nerve growth factor receptorsJ Allergy Clin Immunol199710034084149314355

- MatsumuraSTeraoMMurotaHKatayamaITh2 cytokines enhance TRKA expression, upregulate proliferation, and downregulate differentiation of keratinocytesJ Dermatol Sci201578321522325823576

- WilkinsonDITheeuwesMJFarberEMNerve growth factor increases the mitogenicity of certain growth factors for cultured human keratinocytes: a comparison with epidermal growth factorExp Dermatol1994352392457881770

- OttenUEhrhardPPeckRNerve growth factor induces growth and differentiation of human B lymphocytesProc Natl Acad Sci USA1989862410059100632557615

- BischoffSCCaDDahindenCAEffect of nerve growth factor on the release of inflammatory mediators by mature human basophilsBlood19927910266226691586715

- KesslerJABlackIBNerve growth factor stimulates the development of substance P in sensory gangliaProc Natl Acad Sci USA19807716496526153799

- HägermarkOHökfeltTPernowBFlare and itch induced by substance P in human skinJ Invest Dermatol197871423323581243

- LembeckFDonnererJTsuchiyaMNagahisaAThe non-peptide tachykinin antagonist, CP-96,345, is a potent inhibitor of neurogenic inflammationBr J Pharmacol199210535275301378337

- AlmeidaTARojoJNietoPMTachykinins and tachykinin receptors: structure and activity relationshipsCurr Med Chem200411152045208115279567

- StänderSSiepmannDHerrgottISunderkötterCLugerTATargeting the neurokinin receptor 1 with aprepitant: a novel antipruritic strategyPLoS One201056e1096820532044

- StänderSLugerTMetzeDTreatment of Prurigo nodularis with topical capsaicinJ Am Acad Dermatol200144347147811209117

- SchmelzMSchmidtRWeidnerCHilligesMTorebjorkHEHandwerkerHOChemical response pattern of different classes of C-nociceptors to pruritogens and algogensJ Neurophysiol20038952441244812611975

- LiangYMarcussonJAJacobiHHHaak-FrendschoMJohanssonOHistamine-containing mast cells and their relationship to NGFr-immunoreactive nerves in prurigo nodularis: a reappraisalJ Cutan Pathol19982541891989609137

- SonkolyEMullerALauermaAIIL-31: a new link between T cells and pruritus in atopic skin inflammationJ Allergy Clin Immunol2006117241141716461142

- AraiITsujiMTakedaHAkiyamaNSaitoSA single dose of interleukin-31 (IL-31) causes continuous itch-associated scratching behaviour in miceExp Dermatol2013221066967124079740

- BobkoSZeidlerCOsadaNIntraepidermal nerve fibre density is decreased in lesional and Inter-lesional prurigo nodularis and reconstitutes on healing of lesionsActa Derm Venereol201696340440626338533

- HoeijmakersJGFaberCGLauriaGMerkiesISWaxmanSGSmall-fibre neuropathies – advances in diagnosis, pathophysiology and managementNat Rev Neurol20128736937922641108

- LauriaGHsiehSTJohanssonOEuropean Federation of neurological Societies/Peripheral nerve Society guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint Task Force of the European Federation of Neurological societies and the peripheral nerve SocietyEur J Neurol2010177903e49e944-90920642627

- HollandNRCrawfordTOHauerPCornblathDRGriffinJWMcarthurJCSmall-fiber sensory neuropathies: clinical course and neuropathology of idiopathic casesAnn Neurol199844147599667592

- GorsonKCHerrmannDNThiagarajanRNon-length dependent small fibre neuropathy/ganglionopathyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200879216316917911181

- RosenbergJMHarrellCRisticHWernerRAde RosayroAMThe effect of gabapentin on neuropathic painClin J Pain19971332512559303258

- HoTWBackonjaMMaJLeibenspergerHFromanSPolydefkisMEfficient assessment of neuropathic pain drugs in patients with small fiber sensory neuropathiesPain20091411-2192419013718

- RosenstockJTuchmanMLamoreauxLSharmaUPregabalin for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trialPain2004110362863815288403

- ForstTPohlmannTKuntTThe influence of local capsaicin treatment on small nerve fibre function and neurovascular control in symptomatic diabetic neuropathyActa Diabetol20023911612043933

- GencoglanGInanirIGunduzKTherapeutic Hotline: treatment of Prurigo nodularis and lichen simplex chronicus with gabapentinDermatol Ther201023219419820415827

- MazzaMGuerrieroGMaranoGJaniriLBriaPMazzaSTreatment of Prurigo nodularis with pregabalinJ Clin Pharm Ther2013381161823013514

- DevigiliGTugnoliVPenzaPThe diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathologyBrain2008131Pt 71912192518524793

- PereiraMPPogatzki-ZahnESnelsCThere is no functional small-fibre neuropathy in prurigo nodularis despite neuroanatomical alterationsExp Dermatol2017261096997128370394

- KondaDChandrashekarLRajappaMKattimaniSThappaDMAnanthanarayananPHSerotonin and interleukin-6: association with pruritus severity, sleep quality and depression severity in prurigo nodularisAsian J Psychiatr201517242826277226

- StänderSZeidlerCAugustinMS2k Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pruritus – update – short versionJ Dtsch Dermatol Ges2017158860872

- RichardsRNUpdate on intralesional steroid: focus on dermatosesJ Cutan Med Surg2010141192320128986

- WaldingerTPWongRCTaylorWBVoorheesJJCryotherapy improves prurigo nodularisArch Dermatol198412012159816006508332

- StollDMFieldsJPKingLETreatment of Prurigo nodularis: use of cryosurgery and intralesional steroids plus lidocaineJ Dermatol Surg Oncol19839119229246630706

- BrenninkmeijerEESpulsPILindeboomRvan der WalACBosJDWolkerstorferAExcimer laser vs. clobetasol propionate 0·05% ointment in prurigo form of atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial, a pilotBr J Dermatol2010163482383120491772

- SaracenoRChiricozziANisticòSPTibertiSChimentiSAn occlusive dressing containing betamethasone valerate 0.1% for the treatment of prurigo nodularisJ Dermatolog Treat201021636336620536273

- El-BatawyMMBosseilaMAMashalyHMHafezVSTopical calcineurin inhibitors in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Dermatol Sci2009542768719303745

- SiepmannDLottsTBlomeCEvaluation of the antipruritic effects of topical pimecrolimus in non-atopic prurigo nodularis: results of a randomized, hydrocortisone-controlled, double-blind phase II trialDermatology2013227435336024281309

- WongSSGohCLDouble-blind, right/left comparison of calcipotriol ointment and betamethasone ointment in the treatment of Prurigo nodularisArch Dermatol2000136680780810871962

- SchulzSMetzMSiepmannDLugerTAMaurerMStänderSAntipruritische Wirksamkeit einer hoch dosierten Antihistamini-katherapie [Antipruritic efficacy of a high-dosage antihistamine therapy. Results of a retrospectively analysed case series]Hautarzt200960756456819430742

- ShintaniTOhataCKogaHCombination therapy of fexofenadine and montelukast is effective in prurigo nodularis and pemphigoid nodularisDermatol Ther201427313513924102897

- HammesSHermannJRoosSOckenfelsHMUVB 308-nm excimer light and Bath PUVA: combination therapy is very effective in the treatment of Prurigo nodularisJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201125779980320946583

- WallengrenJSundlerFPhototherapy reduces the number of epidermal and CGRP-positive dermal nerve fibresActa Derm Venereol200484211111515206689

- TartarDBhutaniTHuynhMBergerTKooJUpdate on the immunological mechanism of action behind phototherapyJ Drugs Dermatol201413556456824809879

- Tamagawa-MineokaRKatohNUedaEKishimotoSNarrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy in patients with recalcitrant nodular prurigoJ Dermatol2007341069169517908139

- BruniECaccialanzaMPiccinnoRPhototherapy of generalized prurigo nodularisClin Exp Dermatol201035554955019886961

- SorensonELevinEKooJBergerTGSuccessful use of a modified Goeckerman regimen in the treatment of generalized prurigo nodularisJ Am Acad Dermatol2015721e40e4225497953

- PaghdalKVSchwartzRATopical TAR: back to the futureJ Am Acad Dermatol200961229430219185953

- WizniaLECallahanSWCohenDEOrlowSJRapid improvement of Prurigo nodularis with cyclosporine treatmentJ Am Acad Dermatol20187861209121129438756

- SpringPGschwindIGillietMPrurigo nodularis: retrospective study of 13 cases managed with methotrexateClin Exp Dermatol201439446847324825138

- KlejtmanTBeylot-BarryMJolyPTreatment of prurigo with methotrexate: a multicentre retrospective study of 39 casesJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201832343744029055135

- LearJTEnglishJSSmithAGNodular prurigo responsive to azathioprineBr J Dermatol199613461151

- GuptaRTreatment of Prurigo nodularis with dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapyIndian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol2016822239

- HalvorsenJAAasebøWOral tacrolimus treatment of pruritus in prurigo nodularisActa Derm Venereol201595786686725804254

- FeldmeyerLWernerSKamarashevJFrenchLEHofbauerGFAtopic prurigo nodularis responds to intravenous immunoglobulinsBr J Dermatol2012166246146221910702

- SharmaDKwatraSGThalidomide for the treatment of chronic refractory pruritusJ Am Acad Dermatol201674236336926577510

- ChenMDohertySDHsuSInnovative uses of thalidomideDermatol Clin201028357758620510766

- AndersenTPFoghKThalidomide in 42 patients with prurigo nodularis HydeDermatology2011223210711221952556

- KanavyHBahnerJKormanNJTreatment of refractory prurigo nodularis with lenalidomideArch Dermatol2012148779479622801610

- LimVMMarandaELPatelVSimmonsBJJimenezJJA review of the efficacy of thalidomide and lenalidomide in the treatment of refractory prurigo nodularisDermatol Ther201663397411

- LiuHGaspariAASchleichertRUse of lenalidomide in treating refractory prurigo nodularisJ Drugs Dermatol201312336036123545923

- PhanNQLottsTAntalABernhardJDStänderSSystemic kappa opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic pruritus: a literature reviewActa Derm Venereol201292555556022504709

- LeeJShinJUNohSParkCOLeeKHClinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritusAnn Dermatol201628215916327081261

- DawnAGYosipovitchGButorphanol for treatment of intractable pruritusJ Am Acad Dermatol200654352753116488311

- DevaneCLSubstance P: a new era, a new rolePharmacotherapy20012191061106911560196

- MetzMKrullCHawroTSubstance P is upregulated in the serum of patients with chronic spontaneous urticariaJ Invest Dermatol2014134112833283624844859

- OhanyanTSchoepkeNEirefeltSRole of substance P and its receptor neurokinin 1 in chronic prurigo: a randomized, proof-of-concept, controlled trial with topical aprepitantActa Derm Venereol2018981263128853492

- StänderSKwonPLugerTARandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial of serlopitant effects on multiple measures of pruritus in patients with prurigo nodularisPaper presented at: 9th World Congress on ItchOctober 15–17, 2017Wroclaw

- CornelissenCLüscher-FirzlaffJBaronJMLüscherBSignaling by IL-31 and functional consequencesEur J Cell Biol2012916–755256621982586

- BağciISRuzickaTIL-31: A new key player in dermatology and beyondJ Allergy Clin Immunol2018141385886629366565

- RuzickaTHanifinJMFurueMAnti-Interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitisN Engl J Med2017376982683528249150