Abstract

Background

Lyme disease (LD) is an emerging infectious disease in Australia. There has been controversy regarding endemic lyme disease in the country for over 20 years. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto (Bbss) and sensu lato (Bbsl) are closely related spirochetal species that are the causative agents of LD in humans. Clinical transmission of this tick-borne disease is marked by a characteristic rash known as erythema migrans (EM). This study employed molecular techniques to demonstrate the spirochetal agent of Lyme disease isolated from EM biopsies of patients in Australia and then investigate their genetic diversity.

Methods

Four patients who presented to the author’s practice over a one-year period from mid 2010 to mid 2011 returned positive results on central tissue biopsy of EM lesions using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. The findings were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) analysis was then used to genetically characterize the causative organisms.

Results

Three isolates were identified as Bbss that lay genotypically between strains B31 and ZS7 and were then characterized as strain 64b. One of the three isolates though may have similarity to B. bissettii a Bbsl. The fourth isolate was more appropriately placed in the sensu lato group and appeared to be similar, but not identical to, a B. valaisiana-type isolate. In this study, a central biopsy taken within 6 days of infection was used instead of conventional sampling at the leading edge, and the merits of this are discussed.

Conclusion

These patients acquired infection in Australia, further proving endemic LD on the continent. Central biopsy site of EM is a useful tool for PCR evaluation. BLAST searches suggest a genetic diversity of B. burgdorferi, which has implications concerning the diagnosis, clinical severity, and testing of LD in Australia.

Keywords:

Introduction

Lyme disease (LD) is an increasing health burden on the Australian community requiring wider diagnostic recognition.Citation1 Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bbsl) are closely related spirochetal species that are the causative agents of LD in humans.Citation2 The author has previously reported the endemic presence of LD in Australia by positive serological and molecular testing of blood samples taken from symptomatic patients who have never been abroad, supporting the preliminary observations of others.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4 In the current study, the presence of LD in Australia is confirmed by the detection of Borrelia species (spp.) using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of biopsy tissue taken from patients with a clinical presentation of erythema migrans (EM). The findings were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The use of central biopsy to replace leading-edge biopsy is explored, with indications it is more reliable in detecting Borrelia spp.. Positive findings led to analysis of the sequences deducing preliminary information on Australian genotypes consistent with both B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Bbss) and Bbsl, an important factor in accurate future identification and diagnosis of native infection.

Materials and methods

Skin punch biopsies were taken from the bite sites of four patients presenting with EM, each at a time interval between 1 and 6 days from bite to biopsy. Two biopsies were taken from patient A, one from the central bite site and the other from the leading edge of the lesion. See at day 3, the day of biopsy and commencement of treatment, and at day 6. The sample from the central biopsy of patient A was positive and the leading-edge sample was negative. Prior to this, the author had always been sampling from the leading edge of EM lesions, with consistently negative results. The result on patient A encouraged subsequent sampling using central biopsy only on B, C, and D, which yielded the results in this study. Case A is the index case on a timeline of 1 year in this series. It is of note that all prior leading-edge biopsies taken before the day of patient A’s presentation were analyzed with the same primers about to be discussed for patients A, B, and C. The patients will be referred to as patients A, B, C, and D in this discussion, and biopsies taken from them referred to as biopsies A, B, C, and D respectively.

All specimens were forwarded to Australian Biologics in Sydney for PCR analysis. For specimens A, B, and C, primers for borrelial RNA polymerase gene (rpoC) were employed for amplification using a set of one forward and one reverse. The sequences used are proprietary to Australian Biologics. Specimen D was analyzed with a multiplex set (see ). It was analyzed differently as part of a process of attempting to improve borrelial detection by that laboratory. Cycles, annealing temperatures, and amplicon size are available on request.

Table 1 Multiplex primer set

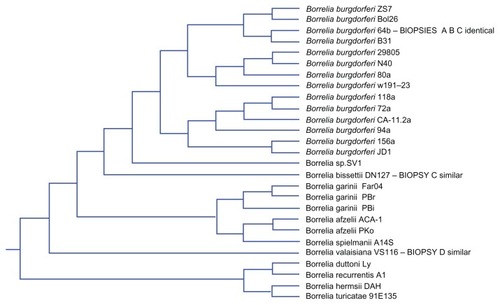

Positive Borrelia DNA product was then submitted to Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) in Sydney for confirmatory testing. AGRF is a National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA) accredited laboratory and is Australia’s largest provider of genomics services and solutions.Citation5 All four sequence results from AGRF were then submitted for basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) inquiry.Citation6 The technique follows in the Discussion section. Then under alignments (third grouping using BLAST) tree analysis using neighbor joining was performed on the results.Citation6 There were unnamed leaves. PathoSystems Resource Integration Center (PATRIC) was then used to examine the sequences, revealing additional findings.Citation7 PATRIC was also used to construct a cladogram of all known Borrelia spp. (see ) but not from the study’s data.

Results

The study identified DNA product suggestive of Borrelia spp. in all four samples. The sequences obtained on the respective specimens are presented in . Each sequence was submitted to BLAST inquiry using that sequence set. Clinicians may like to do the BLAST themselves. The author selected the following BLAST parameters: nucleotide blast > copy the biopsy’s sequence into the “enter accession number” box > database set and choose “others” > program selection and choose Megablast for highly similar sequences > BLAST button at the bottom of the page. Results on A, B and C show detection of Borrelia DNA consistent with Bbss (see ). In particular, results demonstrate strains N40, ZS7, and B31 as equal top alignments with the best match. Patient B has an equal ranking of JD1. This group of results shows a maximum identification (max ident) percentage between 97 and 99 and an extremely low expected value (E). Medical science places much emphasis on probability (P) when interpreting results. Examining P in the BLAST output above, the negative sign in the E value is a negative power. The mathematic constant “e” is 2.7 to one decimal place, and e is raised to that negative power. The distribution of a sequence analysis of this type is a Poisson distribution.Citation8 It is currently believed that with high letter count submissions in these types of sequences that the E value is thought to approximate probability.Citation8 The E value is the expected number of high scoring pairs for a certain nominated score when comparing the alignment of local pairs.Citation8 Algorithms find all segment pairs whose scores cannot be improved by extension or trimming.Citation8

Table 2 DNA sequences

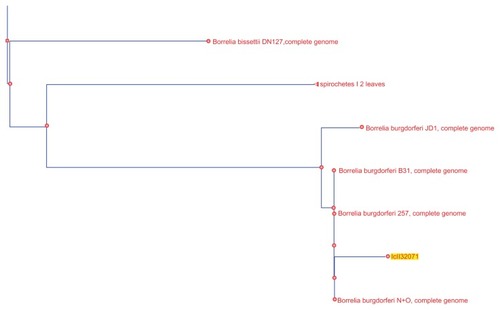

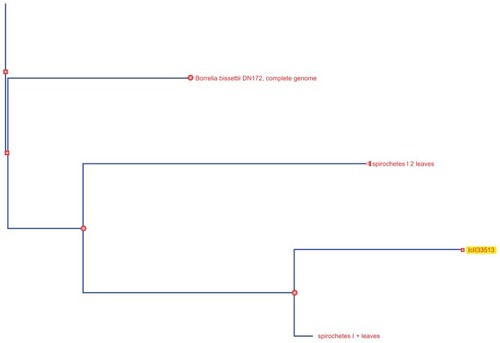

Analysis of the alignments using neighbor joining shows patient A and B samples to be lying identically between Bb ZS7 and Bb B31 (see ).Citation6 Two unnamed nodes lay between those results which are further analyzed below using PATRIC. For patient C, however, the picture is very different. The result on phylogenetic tree analysis appears in the neighborhood of, but distinct from, bissettii DN127, in spite of initial indications suggesting similarity to A and B (see ).Citation6 BLAST comparison alignment using “bl2seq” (this is a selection on the BLAST site for aligning any two sequences) demonstrated that samples A and B are identical (see ). A further paired alignment between samples A and C shows it is very similar in equality but not quite as strong (see ). Both sets of paired alignments had no gaps. Results for BLAST analysis of cloned product from patient D returns “No significant similarity found”. Then using blastn (comparison for similar sequences) instead of choosing Megablast for highly similar sequences, a B. valaisiana-like species is demonstrated.Citation6 Attempts with “bl2seq” to align A, B, and C to D fail. A cladogram of the entire borrelial tree is presented in . It was produced using PATRIC by choosing organisms > bacteria > phylogeny then selecting order spirochaetales and cladogram.Citation7 The result was trimmed to Borrelia spp. The findings from NIHC BLAST were then superimposed in to demonstrate their position. C is duplicated.

Table 3 Top scoring sequences

Table 4 Paired alignment patients A B

Table 5 Paired alignment patients A C

The sequence data was then analyzed at PATRIC producing rather different results.Citation7 For each specimen, the output is some 1400 lines in a spreadsheet. Results are summarized here and show that A, B, and C had identical matches with max ident of 99% and E value of 9 × 10−95 to all of the following Borrelia spp. equally: ZS7, W191-23, N40, CA-11.2A, Bol126, B31, 94a, 72a, 64b, 29805, 156a, and 118a. After several more Borrelia genotypes are listed at much lower max ident and E values, one finds the first non-borrelial bacterium is fusobacterium with an E of just 0.029, and then listeria and campylobacter. This is very compelling evidence of Borrelia spp. Specimen D had a much lower confidence band, with six of the above genotypes at an E of 2 × 10−4. The first non-borrelial listings were three clostridium species with an E of 0.16. Specimen D may be a novel genotype.

BLAST comparison alignment using “bl2seq” from NCBI of the sequences was then used in an attempt to further analyze the specimens using deposited sequences for known Borrelia spp. from Genomic Sequencing Center for Infectious Diseases, University of Maryland, USA, this time demonstrating the 64b serotype.Citation6 The accession number used for whole genome shotgun sequencing and resulting match was Bb 64b ABKA02000001.1. Biopsies A, B, and C were all a positive match. No match could be found for D.

Discussion

Borrelia-specific DNA was detected in all four patient samples. The author proposes detection of Borrelia is more likely to be successful when the specimen is taken from the central bite site than when taken from the leading edge in early lesions. This contradicts convention, the standard long-held practice of biopsy from the leading edge for which there is no published data on PubMed searching on February 10, 2012 using the headings erythema migrans tissue biopsy. Adding the term peripheral finds a paper examining central versus peripheral biopsy by Jurca et al, where the authors conclude that detection from peripheral and central sites was equivalent.Citation9 It has been thought that Borrelia DNA detection from EM rashes at the leading edge is successful in 80% of cases.Citation10 This statement by Sydney University is not itself referenced. The current study suggests that employing central site of biopsy may reliably provide detectable spirochetal DNA evidence up to 6 days after tick attachment, even after tick removal. All patients received their tick bite within 10 kilometers of the eastern coastline in the state of New South Wales. A and B were only 12 km apart but with a time gap of 1 year. Patient C was in the northern suburbs of Sydney. Patient D was some 80 km north of patients A and B. Patient D had presented multiple times with EM over a 1-year period. He had protracted chronic LD, and lesion edge biopsies were negative prior to this attempt to determine whether a B. burgdorferi spp. was responsible. On this last presentation, a biopsy taken from the central bite site was positive for B. burgdorferi spp., again supporting the concept of central biopsy.

For the past two decades there has been considerable debate concerning the existence of LD on the continent of Australia. There are two longstanding published reports of both EM and locally acquired human B. burgdorferi infection and one contrary.Citation3,Citation4,Citation11 At the time of the McCrossin study in 1986, only serological diagnostic tests were available.Citation3 So sequencing was not possible for confirmation of those results. The Russell et al study in 1994 examined the midgut content of over 12,000 mostly unfed ticks with no spirochetes found.Citation11 However, it is now known that spirochetes within flat, or unfed, nymphs exist in low numbers and in a poorly understood metabolic state that enables them to endure prolonged periods of nutrient deprivation. In this state, the transcription regulators Rrp2–RpoN–RpoS and the hybrid histidine Hk1–Rrp1 pathways are inactive, as are mammalian-phase genes, while tick-phase genes are maximally expressed.Citation2 At the commencement of feeding, this status is reversed with rapid replication.Citation2 Then, under the heading “Within the mammalian host” a clear model of salivary hypostome spirochete movement from tick to skin is described.Citation2 The Russell study’s negative findings may no longer be appropriate. The Hudson study in 1998 described a cultured isolate of Borrelia identified by molecular testing from one patient who had travelled overseas but due to the length of time since overseas travel (17 months) it was believed the patient acquired their infection in Australia. Sequencing results suggest similarity to a European strain of B. garinii, rather than the B. garinii species typically described in Asia.Citation4 In a 2011study, the current author published serological and molecular evidence of endemic Lyme borreliosis in Australia, reporting positive LD test results of whole blood and serum taken from patients who had never left the country.Citation1 The current study provides further proof of endemicity of Borrelia infection in Australian patients using molecular detection of Borrelia DNA from biopsy material. This is a small study based on four samples. Further investigation is required to determine if there are novel Borrelia genotypes in that a B. bisettii-like organism and a B. valaisiana-like organism are suggested from the data of patients C and D respectively. Further genotyping studies should be done to confirm or disprove the serotype 64b nature of specimens A and B.

In the expanding universe of B. burgdorferi, in addition to small mammals, transhemispheric bird migration is responsible for spirochete dissemination.Citation2,Citation12 Although Australia has approximately 75 tick species, it is generally accepted that Ixodes spp., and Ixodes holocyclus (Ih) in particular, are the main contenders in transmitting human tick-borne diseases.Citation13,Citation14 The Eastern coastline is habitat to Ih, which is known to vector human disease, including rickettsial infection and tick paralysis.Citation1,Citation13–Citation16 The Ih tick is colloquially named paralysis tick.Citation10 It may also be called grass tick, shell back tick, and several others. It thrives in humid coastal conditions, mainly in flatlands, from the north of the continent just above Cooktown in Queensland to Lakes Entrance in Victoria at the very south of the continent.Citation10 This region contains a very high proportion of Australia’s human population.

The Ih tick has larval, nymph, and adult stages all of which require a blood meal.Citation10 Larvae typically feed upon small animal hosts, whilst the nymph and adult will also feed upon larger animals.Citation2,Citation10 Humans are incidental hosts to all three forms, but the nymph is primarily responsible for 90% of human tick-borne disease.Citation2 The tick may stay attached for up to 5–6 days before detaching if not found. Many tick bites are not observed or reported.Citation1 In Australia, the majority of bites will come to nothing more than an erythematous macule (nonelevated) on the skin, of up to 2 cm diameter, resolving completely over a few days, providing the tick is removed promptly. Some lesions grow at the bite site to form a 2–3 cm papule by the second day, showing a black central eschar.Citation17 Such a presentation at the bite site is the typical appearance of Queensland tick typhus, a rickettsial infection, and if untreated, this can be followed by a “spotted rash” of widespread distribution known as rickettsial spotted fever, a febrile illness whose erythematous macules are typically 4–5 mm in diameter.Citation15,Citation16

EM is a local clinical manifestation of Bbsl infection.Citation2,Citation18,Citation19 The incubation period is 3–32 days.Citation2,Citation20 At this stage, the term early LD is also used, and this terminology includes early systemic manifestations such as meningitis, cranial nerve neuropathy, or carditis. An EM documented on an individual after being in a known endemic area is considered sufficient for a clinical diagnosis of LD; however, the single primary lesion must reach more than 5 cm in size to be classified as diagnostic and to be considered pathognomonic.Citation21 The EM is often described as an initial 1 cm macular erythematous lesion, that at day 2–5 or even later, grows in diameter and thickens, lasting for up to 14 days or more if left untreated. Spirochetes are deposited into the skin during initial attachment.Citation2 In the Northern Hemisphere, infection is rare in the first 24 hours after tick bite but most likely after 48 hours.Citation2 Australia does not have enough data to confirm whether this is true locally.

LD is a protean multisystem illness that develops after a tick bite transmitting human pathogenic Borrelia spirochete when the initial local reaction is not treated or is under treated.Citation22 Nomenclature of the disease includes the use of the terminology early disseminated LD and late disseminated LD.Citation23 The International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society uses the terminology chronic LD for infection lasting more than 12 months.Citation22 In North America, a principal symptom of the disease is an arthritic illness that may cause severe pain and swelling, especially in large joints, and can be associated with marked general fatigue and other somatic features.Citation22 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website states that in the musculoskeletal system, LD produces recurrent attacks of arthritis with objective joint swelling in one or a few joints, sometimes followed by chronic arthritis.Citation23 LD in North America may also be present as a neurological disease, which is generally accepted to be the principal manifestation throughout Europe and Asia.Citation24 The author has presented similar findings of neurological manifestation with locally acquired LD in Australia with no arthropathy.Citation1

Current thought is that Borrelia spp. are found along the eastern coastline of Australia and transmitted to humans by Ih.Citation1 This study is implicating the same vector for transmission. Patients A and B received their tick at the same latitude but with a time gap of 1 year. Clinically, both patients reported painful itchy swellings of their EM. From a clinical standpoint, the two Bbss genotypes caused an infection characterized by an intensely painful itchy eruption, one without significant systemic event. Refer to for a summary of the clinical detail. On the contrary, in patient C, the EM eruption was not particularly sore or itchy. This infection, with the possible B. bissettii-like genotype, in addition to producing local reaction, produced a profound systemic meningitic illness that lasted many weeks. The infection was contracted in the northern beachside region of Sydney.

Table 6 Demographic data and clinical details

There is conflict in the findings for patient C with one method of analysis, suggesting Bbss 64b and the other (neighbor joining tree) a similarity to B. bissettii. This distinction needs further research and clarification, and in particular, note should be taken that clinical manifestation was different. Patient C received the tick bite in Northern Sydney. It is of clinical significance that this infection could not be controlled quickly with the amoxycillin clavulanate combination taken orally, and is an indicator of possible coinfection of babesiosis or bartonellosis. The author has already presented the independent incidence rate of these as 31% and 21% in Australia in associated tick-born diseases.Citation1

Patient D had symptoms of protracted neurological LD on first presentation and had leading edge skin biopsies of EM done by the author, which returned negative as discussed above. Central biopsy on this occasion was positive and showed the B. valaisiana-like organism. This being the first human report of such a species in Australia warrants further research.

The terminology “Lyme-like” crops up frequently in Sydney, Australia. There are no published reports of a Lymelike illness in Australia using a PubMed search with the term “Lyme-like Australia” on January 24, 2012. The term “Lymelike illness” on this continent could now be considered, as the study presents some identity pointer to the wider Borrelia spp. infections as in patient D. “Lyme-like illness” has differing connotations. It is used appropriately to describe clinical infection by Borrelia that fall outside the sensu lato group, particularly in Europe and the USA where there are an increasingly growing number of genospecies of Borrelia being identified. It is being wrongly interpreted by media and Australian compensation insurance companies as a possible Lyme illness, lacking serological proof of borrelial infection. The identity of the genotype in patient D would appear to fit this appellation of Lyme-like illness.

Although the sample size is small, the relationship between the clinical presentations, the genotype involved, and geographical distribution demonstrated here may all be relevant to the development of local testing modalities, successful diagnosis of LD, and the subsequent clinical severity of disease.

Conclusion

Firstly, the results provide objective evidence confirming endemic LD in Australia by detecting and characterizing Borrelia genotypes of the Bbss group from biopsies of EM. Thus, LD must be considered to be a potential health risk in Australia. Possible identity to a Lyme-like illness in Australia is suggested as a valaisiana-like genotype.

Secondly, it is suggested that the success of Borrelia spp. detection from EM tissue can be greatly improved. The author’s findings indicate that during the first week of EM eruption, tissue biopsy at the bite site is preferable to that at the leading edge.

Thirdly, the evidence provided suggests that further research is needed to elucidate the genetic diversity of Borrelia spp. and B. burgdorferi genotypes causing LD on the continent of Australia. At least two and possibly three distinct genotypes are suggested, one characteristic of Bbss genetically lying between strains B31 and ZS7 and looking like 64b, one possibly related to, but discrete from, B. bissettii DN127, and finally a B. valaisiana-like genotype. This is a small study on four patients. More extensive studies are needed to make firmer conclusions. The genetic diversity of Borrelia spp. associated with LD has diagnostic laboratory and clinical significance to the medical profession and has implications for assessment of public health risk.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Jennifer Burke MSc, Dr Peter Irwin, Dr Andrew Ladhams, Marianne Middleveen MSc, Janet Sperling MSc, Dr Felix Sperling, and Dr Raphael Stricker for their advice in the preparation of this paper.

The author is a member of the International Lyme and Associated, Diseases Society (ILADS)

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MaynePJEmerging incidence of Lyme borreliosis, babesiosis, bartonellosis, and granulocytic ehrlichosis in AustraliaInt J Gen Med2011484585222267937

- RadolfJCaimanoMStevensonBHuLOf ticks, mice and men: understanding the dual-host lifestyle of Lyme disease spirochaetesNat Rev Microbiol201210879922230951

- McCrossinILD on the NSW south coastMed J Aust19861447247253724608

- HudsonBStewartMLennoxVCulture-positive Lyme borreliosisMed J Aust19981685005029631675

- AGRF Australian Genome Research Facility Ltd [homepage on the Internet]Sydney, AustraliaWestmead Millenium Institute Available from: http://www.agrf.org.auAccessed February 11, 2012

- BLAST® Basic Alignment Search Tool [homepage on the Internet]Bethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health, National Center for Biotechnology Information Available from: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.govAccessed February 11, 2012

- PATRIC, Pathosystems Resource Integration CenterBacteria spirocheates phylogenetic tree cladogramBlacksburg, VAVirginia Bioinformatics Institute Available from: http://patricbrc.org/portal/portal/patric/Phylogeny?cType=taxon&cId=203691Accessed February 11, 2012

- NCBI The statistics of sequence similarity scoresBethesda, MDNational Institutes of Health, National Center for Biotechnology Information Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/tutorial/Altschul-1.htmlAccessed February 11, 2012

- JurcaTRuzić-SabljićELotric-FurlanSComparison of peripheral and central biopsy sites for the isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from erythema migrans skin lesionsClin Infect Dis1998276366389770166

- Department Medical EntomologyLyme diseaseSydney, AustraliaUniversity of Sydney [updated November 7, 2003]. Available from: http://medent.usyd.edu.au/fact/lyme%20disease.htm#diagAccessed February 11, 2012

- RussellRCDoggettSLMunroRLyme disease: a search for the causative agent in south-eastern AustraliaEpidemiol Infect199411223753848150011

- OlsenBDuffyDCJaensonTGGylfeABonnedahlJBergströmSTranshemispheric exchange of Lyme disease spirochetes by seabirdsJ Clin Microbiol19953312327032748586715

- NSW Government HealthTicksNSW, AustraliaNSW Government Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/factsheets/general/ticks_factsheet.htmlAccessed February 11, 2012

- MurtaghJMurtagh’s General Practice5th edSydneyMcGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd2011267

- UnsworthBStenosJGravesSFlinders Island spotted fever rickettsioses caused by “marmionii” strain of Rickettsia honei, Eastern AustraliaEmerg Infect Dis200713456657317553271

- UnsworthNGravesSNguyenCKempGGrahamJStenosJMarkers of exposure to spotted fever rickettsiae in patients with chronic illness, including fatigue, in two Australian populationsQJM2008101426927418287113

- Department of HealthInfectious diseases, epidemiology and surveillanceVictoria, AustraliaState Government of Victoria Available from: http://ideas.health.vic.gov.au/bluebook/rickettsial.aspAccessed February 11, 2012

- DermNetNZLyme diseasePalmerston North, New ZealandNew Zealand Dermatological Society Available from: http://www.dermnetnz.org/bacterial/lyme.htmlAccessed February 11, 2012

- MülleggerRRGlatzMSkin manifestations of lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and managementAm J Clin Dermatol20089635536818973402

- RadolfJSalazarJDattwylerRBorrelia: molecular biology, host interaction, and pathogenesisNorfolk, UKCaister Academic2010487533

- FederHAbelesMBernsteinMWhitaker-WorthDGrant-KelsJDiagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of erythema migrans and Lyme arthritisClin Dermatol200624650952017113969

- International Lyme and Associated Diseases SocietyAbout Lyme diseaseBethesda MDInternational Lyme and Associated Diseases Society Available from: http://www.ilads.org/lyme_disease/about_lyme.htmlAccessed February 11, 2012

- CDC Lyme disease signs and symptomsAtlanta, GACenters for Disease Control and Prevention Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/signs_symptomsAccessed February 11, 2012

- RudenkoNGolovchenkoMGrubhofferLOliverJHJrUpdates on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public healthTicks Tick Borne Dis20112312312821890064