Abstract

Hair loss is a common problem affecting both men and women. The most frequent etiology is androgenetic alopecia, but other causes of hair loss such as trauma, various dermatologic diseases, and systemic diseases can cause alopecia. The loss of hair can have profound effects on one’s self esteem and emotional well-being, as one’s appearance plays a role in the work place and interpersonal relationships. It is therefore not surprising that means to remedy hair loss are widely sought. Hair transplant surgery has become increasingly popular, and the results that we are able to create today are quite remarkable, providing a natural appearance when the procedure is performed well. In spite of this, hair transplant surgery is not perfect. It is not perfect because the hair transplant surgeon is still faced with challenges that prevent the achievement of optimal results. Some of these challenges include a limit to donor hair availability, hair survival, and ways to conceal any evidence of a surgical procedure having taken place. This article examines some of the most important challenges facing hair restoration surgery today and possible solutions to these challenges.

Introduction

Hair transplantation has become a well established procedure for the treatment of hair loss due to androgenetic alopecia (AGA) as well as for hair loss due to trauma and some forms of inflammatory hair disorders. Hair replacement surgery appears to date back to Japan. An article by Okuda in 1939Citation1 reported the transfer of single hairs, but it was not until OrentreichCitation2 that the transfer of large amounts of hair could be accomplished, and the concept of hair transplantation for treating baldness became popularized. While patients did grow hair, the grafted hair, done with large “plugs”, gave an odd, plug-like appearance. Attempts to alleviate this esthetically unpleasing result led to the use of smaller grafts, such as mini grafts, strip grafts, and single-hair micro grafts.Citation3

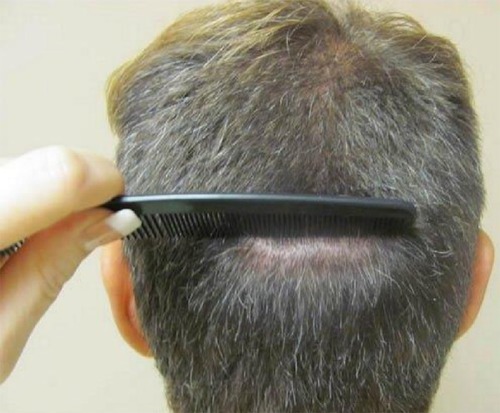

It was not until the advent of the concept of follicular units (FUs)Citation4 () and follicular unit transplantationCitation5,Citation6 that modern hair replacement evolved sufficiently to provide truly natural results. Additionally, a better appreciation of hair line esthetics and increased knowledge of the androgenetic hair loss process over one’s lifetime gave physicians the ability to create extraordinarily natural outcomes.Citation7–Citation9 The use of FUT done in an appropriate manner allows patients to stop anywhere along the course of hair transplantations and still have a normal balding pattern result.Citation10

Figure 1 View of scalp hair demonstrating follicular units. These are naturally occurring clusters of hair in the scalp and usually occur as single hairs, two-hair or three-hair groupings.

While the evolution of hair replacement surgery has afforded us the ability to create excellent results, we still face situations where patient expectations cannot be reached. Challenges exist that limit our ability to produce results that rival hair in its natural state. What are the challenges the hair transplant surgeon faces and what may be possible solutions?

In this article, we delve into these issues, and do so by systematically looking at the challenges in the areas of donor surgery, graft preservation, optimization of growth, donor preservation and possible enhancement, improved graft survival, and possible regeneration of hairs in areas of bald scalp.

Donor area challenges

Donor area surgery, strip harvesting donor scars, and follicular unit extraction/follicular isolation technique scars

Over the past 10 years, there has been increased concern about the donor area scar that results from strip harvesting.Citation11 The resulting scar can be disfiguring and apparent when the hair in the donor area is not long enough or thick enough to conceal it. The cause of such disfiguring scars often relates to poor surgical decisions, such as taking too much tissue, thus making closure difficult, but it can also relate to patient skin characteristics that do not promote good healing. Recognizing these parameters, physicians have learned to more accurately assess scalp laxity and limit the width of the excision, so as to avoid excessive tension upon closure and therefore create more esthetically acceptable scars. When the donor surgery is done well, the patient can wear his or her hair quite short without any evidence of the surgical procedure.

In an effort to improve the donor scar outcome, the trichophytic closure promoted by Rose,Citation11 Frechet,Citation12 and MarzolaCitation13 has proved to be very helpful. The basis of the closure is to remove the epidermal edge from the inferior or superior aspect of the donor wound to create a sloping or ledge type edge (–). The opposing side is then brought to the trimmed epidermal side to allow for a slight overlap. By trimming the epidermal edge at a level that does not affect hair growth, hair can grow through the scar to assist in hiding the donor scar. In many instances, this can result in a scar that is extremely difficult to find, allowing the patient to wear his or her hair very short in the donor region.

Figure 2 Photograph demonstrating the removal of the epidermal edge and creation of the ledge. Once the epidermal edge is removed, the wound is then sutured so that the superior edge slightly overlaps the inferior edge.

Figure 4 Post-operative result of the same trichophytic closure, close up. Note that the person could wear his hair quite short and that there would be no evidence of the prior surgical procedure.

The author prefers to use the inferior edge of the donor incision and trim to a width of 1–2 FUs and depth of close to 1 mm. The author also uses a scalpel to create a right angle edge. This method differs from another method in which physicians use scissors, which creates a sloped edge. Other physicians have suggested different devices to trim the epidermal edge,Citation14,Citation15 and it has been suggested that both sides of the incision be trimmed.

As an aid to healing, some physicians have begun to employ platelet-rich plasma (PRP). PRP has been used for many years to enhance wound healing.Citation16,Citation17 PRP is prepared by taking a small amount of the patient’s blood; then, using a centrifuge, it is spun down to create a layer of concentrated platelets. The platelet layer can be removed, and the platelets can then be injected into the donor wound area. PRP contains numerous factors that can aid in healing, such as platelet-derived growth factor, interleukin-8, insulin growth factor, transforming growth factor beta, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor.Citation16 It would seem reasonable to consider using this in an attempt to facilitate healing of the strip incision.

Recently, some physicians have started using extracellular matrix material (ECM), to try to improve wound healing. Over the past few years, ECM has been utilized in orthopedic surgeries, wound healing, and in gynecologic and urologic procedures.Citation18 It has attracted the attention of hair restoration surgeons, and several are exploring the use of this material.Citation6 ECM serves as a bioscaffolding material that contains various proteins, proteoglycans, and cellular factors.Citation18 These components might serve as a source for cell regeneration. The most commonly used ECM used in hair restoration is derived from porcine bladder (MatriStem® device; ACell, Columbia, MD, USA). It is unique in that it contains basement membrane.Citation19 Like PRP, ECM such as MatriStem contains bioactive factors. These include vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor, keratin growth factor, bone morphogenetic protein, insulin-like growth factor, hepatic growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor. ECM also contains various forms of collagen as well as elastin, laminin, and fibronectin. An important property of ECM is that it does not elicit an immune reaction, and some physicians are using ECM in the strip incision closure to aid in healing.Citation20,Citation21

The concern about a donor linear scar has led to the advent and increasing acceptance of the follicular unit extraction/follicular isolation technique (FUE/FIT).Citation22,Citation23 With this method, FUs are harvested with a small punch, usually 0.8–1.1 mm in diameter. Removal of the FUs creates round scars. These scars are often hypopigmented and larger than the original punch size. The author has hypothesized that when numerous FUs are harvested in an area, there is a loss of the usual contractile forces that would normally serve to contract a wound. The ideal result would allow a patient to shave his or her head without any evidence of the punch harvesting and to avoid a “buckshot” appearance. Several solutions have been suggested and tried. The author has developed a suction system to try to improve these wounds.Citation24 Some physicians have begun to utilize PRP with or without ECM placed into the wound in an attempt to obtain improved healing.Citation21

Using the experience of porcine bladder ECM in strip scars, some physicians have tried to place ECM into wounds created by FUE/FIT in an effort to heal the scars and possibly grow hair in these wounds. There is a report of MatriStem placed into FUE wounds and subsequent healing with regeneration of some hairs.Citation20 Cooley has observed that ECM seems to work to grow hairs only if the surrounding hairs in the area are damaged to some extent.Citation20 This would suggest that appropriate damage to the peripheral hairs provides the necessary signals to induce hair growth in the “damaged” area and push the stem cells to initiate hair formation. Could this be a way to partially replenish hairs in the harvested donor area?

A novel way to improve the donor scars from strip or FUE/FIT is the use of scalp micropigmentationCitation25 ( and ). This procedure essentially tattoos the skin. Small amounts of dye deposited at a superficial depth can give the impression of hair when performed adeptly. This technique has also been employed in the recipient area when donor hair is not available to create the impression of density or simply give the appearance of coverage. The technique is performed using local anesthesia. When the full scalp is treated, the time for such a procedure may be in excess of 6 hours.Citation21

The donor area; robotic FUE/FIT, and piloscopy

Originally, physicians performed FUE/FIT manually with a hand-held punch. Although many physicians performing FUE/FIT have switched to electrically powered drills with the punches, the technique nevertheless still calls for superior hand–eye coordination, physical stamina, and a clear understanding of hair anatomy as it relates to the path of hairs coursing through the skin.Citation26 Because the learning curve is very difficult, many physicians have been reluctant or unable to perform this manual technique. When the patient requires large numbers of grafts in a single session, the physical strain on the physician can be of concern.

When first learning how to perform the technique, it is not unusual for surgeons to harvest at a rate of less than 100 grafts an hour.Citation6 This presents a major problem when one is seeking to acquire high numbers of grafts. Concomitantly, the physician must be concerned with the rate of transection of hairs and fragility of these grafts. The use of mechanized devices has helped to improve harvest rates, but the skill needed to remove the grafts remains. It is noted that some physicians who use a manual technique can harvest at speeds that often exceed 600 grafts per hour with low transection rates, but this is not usually the case.

In an effort to remove the obstacles to learning FUE/FIT, provide low transection rates and quality grafts, a robotic device has been developed.Citation27,Citation28 This system consists of a computer interface, robotic arm, and ergonomic chair. The robotic arm has video cameras that display the donor area to be harvested. All of the FUs in a given area are identified, and using an algorithm that randomly selects a portion of the available FUs, the grafts are then obtained. The robotic arm has a double-barrel needle system. One needle enters to the depth of the epidermis, while the second needle cores out the graft. Various parameters can be controlled by the physician and computer operator. The physician can control the angle of attack, revolutions per minute (rpm) of the needle, depth of penetration of the needle, and the coring needle.

The robotic system is an excellent approach to the repetitive action required for FUE/FIT. Typically, the robotic system can harvest at a rate of 500 or more grafts per hour, with transaction rates of 1%–7%, in the author’s experience. As with manual or mechanized drills, similar problems exist. There may be difficulty harvesting very curly hair, as the robotic needle cannot always accommodate the curvature of the follicles in these patients. The wounds created may hypopigment or hyperpigment. The wounds may be larger than the original punch. Buried grafts may occur. Importantly, with successive harvests, there can be thinning of the donor area that may become apparent. Also, as with other types of FUE/FIT, there may be a temptation to harvest outside what is considered to be the safe area of permanent hair in an effort to achieve greater graft counts. This could result in grafts being used containing hairs that are actually destined to be lost due to the androgenetic process.

Wesley has developed a different approach to obtaining FUs by FUE/FIT.Citation29 He refers to his method as “piloscopy”, and he has developed prototypes of an endoscopic device that can harvest grafts from under the skin. With this device, a small incision is made in the donor area, and the endoscopic device is inserted to the level of the fascia. A camera displays the bulbs of the various FUs, and the device is then manipulated so as to grasp the selected FUs at a level approximately 1 mm below the skin. With this method, the outer surface of the skin is not penetrated, and no evidence of the surgery in terms of a donor scar would be present. Such a technique would eliminate the hypopigmentation often present as a residual effect of FUE/FIT harvesting.

Preserving harvested donor hair

Holding solutions

A crucial aspect to hair replacement is the preservation of grafts when they are outside of the body awaiting transplantation. Historically, chilled saline or Ringer’s lactate have been the most commonly used media to store grafts in.Citation30 Clearly, these solutions have worked well, as evidenced by the results produced by competent hair restoration surgeons. Studies have demonstrated that hairs can survive well in such chilled solutions for almost 8 hours before showing evidence of decreased survival.Citation31 Nevertheless, if we can increase the numbers of grafts that survive after harvesting, such an increased survival can only benefit the patient in preserving donor supply and in providing a better result. The knowledge that re-perfusion injury occurs with re-implantation of tissueCitation32–Citation34 and the fact that cases are becoming larger in terms of number of grafts, thus necessitating that grafts be out of the body longer than previously, has caused us to reconsider what might be the best way to preserve grafted hair. The goal is to try to ensure that every hair removed from the donor area survives implantation and goes on to yield viable hairs.

Studies have shown us that there is a profound effect on sodium and potassium pumps and calcium channelsCitation32 due to hypoxic conditions, and that the cellular changes associated with implantation of grafts involve a release of free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Studies by Krugluger et al have shown that using antioxidants and various buffers can markedly reduce shedding of transplanted hair post-operatively, and growth is improved.Citation35

Toward this end, some physicians have begun to utilize a solution used for organ transplantation. One of the more popular solutions is HypoThermosol® (BioLife Solutions, Seattle, WA, USA). This is a product that is protein-free and designed to be used at 2°C–8°C. The manufacturer has indicated that the solution diminishes stress on cells that occurs with chilling and subsequent re-warming. The manufacturer advises the material is able to “scavenge free radicals, support energy substrates and provided oncotic and osmotic support”. It is marketed as a product that can decrease apoptosis and necrosis of tissue.

A study by Cooley looked at storing grafts for 5 days at 4°C. A portion of the grafts was stored in a solution of HypoThermosol plus adenosine triphosphate (ATP), some in HypoThermosol alone, and the remainder in saline. The grafts were implanted into the patient after 5 days, and when reassessed at 18 months, 72% of the hairs had grown in the HypoThermosol and ATP group, 44% in the HypoThermosol group, and none in the saline group.Citation36

Once harvested, hair transplant grafts are obviously without a blood supply and oxygen while sitting in a holding solution; the cells are unable to produce normal quantities of ATP. Furthermore, once implanted, the grafts will not acquire their own specific blood supply for approximately 5 days. For these reasons, it has been suggested that surgeons consider adding ATP to the holding solutions.Citation37 The form of ATP currently being used by some surgeons is a liposomal encased ATP manufactured by Energy Delivery Solutions (Jeffersonville, IN, USA). In one study examining the use of HypoThermosol and ATP versus saline, grafts were left outside the body for 96 hours and stored in either refrigerated HypoThermosol plus ATP or in saline alone. The grafts were then implanted. The results showed that the grafts placed in HypoThermosol plus ATP had enhanced survival.Citation37

Some physicians have advocated the use of liposomal ATP (Energy Delivery Solutions) placed into a copper peptide post-operative spray. Use of the ATP in the spray seems to push implanted hairs into a growth phase sooner, and the hairs appear more robust than with copper peptide spray alone. Cooley has also noted that using a post-operative spray with liposomal ATP has led to fewer instances of decreased growth.Citation36

Preserving donor hair and regenerating existing miniaturizing hair

Drug therapy

An ongoing challenge in hair restoration is preventing hair loss in patients destined to have AGA. How can we preserve hair when there is already hair loss? By limiting hair loss, we can hopefully reduce the need for increased numbers of grafts to be placed into an area of alopecia. A means to early diagnosis such as genetic mapping might be helpful in starting medical therapy early.Citation38 We can often ascertain that a person is destined to have hair loss based on a review of the males and females with hair loss in the family, but having a more accurate method might be useful.

A major breakthrough in understanding the mechanism of male pattern hair loss occurred with the recognition of the role of dihydrotestosterone (DHT). With this knowledge, it became apparent that drugs that could block the chemical pathway to DHT could prevent or forestall hair loss due to male pattern alopecia. Currently, the most effective pharmaceutical agent to diminish hair loss is finasteride.Citation39–Citation42 This drug works by blocking the conversion of testosterone to DHT via one of the 5-alpha reductase pathways. There is concern among patients about side effects such as decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and prostate cancer. While there is an incidence of sexual side effects of approximately 2%–5%, by decreasing dosing, these problems can often be overcome. The fears of increased prostate cancer appear to be unsupported.Citation43,Citation44

A drug similar to finasteride is dutasteride. This drug blocks both of the alpha reductase pathways.Citation44 It has been utilized for prostate enlargement but has not been widely used for hair loss. There are concerns that sperm count can be lowered permanently. This would be of particular concern in young men seeking to conceive a child.Citation41

Another commonly used medication is minoxidil. This drug was originally used to control hypertension. A side effect was hirsutism, and thus began the use of minoxidil for hair growth.Citation45 The mechanism of action is not clearly elucidated, but it seems that the drug acts on potassium channels. It was once thought the stimulatory effect was due to vasodilatation, but this has been shown to be untrue.Citation46

One drug that may prove useful for AGA is bimatoprost.Citation41 This drug is a prostaglandin analog. It has been marketed as Latisse® (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), which is prescribed primarily to women for stimulating growth of eyelashes and eyebrow hair. Bimatoprost is under investigation as a possible drug for increasing scalp hair growth in men.Citation41 In a study published in 2012, a prostaglandin analog latanoprost, was used topically. The study lasted 24 weeks and the drug was shown to improve hair growth in male patients with AGA.Citation47

Low-level laser therapy

Low-level light lasers have been advocated by some physicians to re-grow hair. The use of such laser is based on the work of Mester et al,Citation48 who reported on the effects of low energy laser light on hair growth in mice. Mester et al utilized a ruby laser generating a wavelength of 694 nm.Citation48 Since that time, such lasers have been shown to be useful for wound healing.Citation49

Studies have demonstrated that the effects of such low-level lasers occur at the mitochondria, affecting the cytochrome c oxidase pathway and thus, production of ATP and DNA.Citation50,Citation51 The induction of ATP is believed to activate various cellular factors including cytokines and growth factors. It has been demonstrated that lasers affect the nitrous oxide pathways, which may be beneficial for wound healing and other cellular interaction.Citation51 With respect to hair, it is thought that the use of laser light can stimulate hairs to re-enter anagen phase and stay in anagen longer.Citation51 There is a strong case to be made that lasers can affect hair growth and character of hair, but there are relatively few studies that document the effects with double-blind placebo-controlled investigation. A study in 2009Citation52 looking at the LaserMax device, 655 nm (Lexington International, LLC, Boca Raton, FL, USA) showed an increase in terminal hairs as well as an increase in the caliber of hairs, and improved texture. Several recent studies using the comb device demonstrated an increase in terminal hairs and hair diameter.Citation53–Citation55 It is known that that cells in culture, when exposed to certain wavelengths of low-level laser light, produce an increase in DNA synthesis. The increase in DNA production is linked to the following ranges of wavelength: 614–624, 668–684, 751–772, and 813–846 nm.Citation56,Citation57

Numerous low-level laser devices are commercially available to consumers. Most devices are portable and come in various configurations, such as combs or hats. Some units are portable, while others are standing units. The differences between devices are usually the number of lasers/diodes used, the configuration, and the total output. The devices are considered to be class II US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) devices, and while considered safe, a Section 510(k) is required for legal sale.

While the use of lasers is growing, there remain questions about these devices. What is the optimal wavelength? Keene has pointed out that while there are several DNA activity peaks, the lasers on the market do not seem to use any of the exact wavelengths shown to induce DNA activity.Citation57 What is the optimal time for use and power for a given configuration of lasers? Is there an inhibitory effect at a certain power level? What is the level of penetration for each laser device? Where in the tissue or hair follicle is the laser having effects? Many devices are available, and these may be considered safe, but many do not have the necessary US FDA clearance.

Prostaglandins

In 2013, Garza et alCitation58 published a report indicating that prostaglandins play an important role in hair growth activity and the loss of hair in both men and women experiencing AGA. They looked at bald scalps from men experiencing AGA as well as hair-bearing scalps in men with AGA. The areas of bald scalp had much higher levels of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and 15-deoxy-delta-12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15dPGJ2). They noted PGD2 synthase activity was higher in the bald scalp as a result of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and thus increased protein production. Their work showed that both PGD2 and 15dPGJ2 inhibit hair growth. When used in a mouse model, exogenous PGD2 was shown to decrease the growth of hairs.

One could imagine that a therapy that reduces or inhibits PGD2 production might be beneficial in treating AGA. Adding a prostaglandin such as PGE might work to enhance hair growth. Another approach might be to use mRNA inhibition as a means to turn off the genes making the PGD2.

Work by Magro et alCitation59 has shown that there is an inflammatory infiltrate associated particularly with female pattern hair loss. It is conceivable that diminishing the inflammatory response might improve hair growth. Various prostaglandins are associated with the inflammatory response, so utilizing anti-inflammatory prostaglandins or inhibiting the ones that promote inflammation might aid in decreasing hair loss in these patients.

Optimizing growth in the hair transplant recipient area

PRP

PRP has been advocated as a way to preserve hair and possibly grow hair.Citation60–Citation64 As noted in the previous section Donor Area Challenges, PRP contains numerous growth factors that are presumably released into the tissue where PRP is introduced. However, there are some aspects of the use of PRP that remain problematic in determining efficacy. Physicians should recognize that there are multiple companies that supply PRP materials and devices for preparation. Each company suggests that their technology is superior. Also, it is unclear what concentration of platelets is optimal, what volume should be used, what depth the material should be injected at, what spacing should be used, whether all white blood cells should be removed, whether all red blood cells should be removed, how the material should be activated, and whether release of factors should be slow or fast.Citation16 Well-designed studies answering these questions related to PRP and human hair growth are lacking. A large amount of the evidence is anecdotal. Interesting research by Miao et alCitation65 has demonstrated a positive effect of PRP on hair follicle formation when epidermal cells and dermal papilla (DP) cells were mixed with PRP in the mouse model. Whether the mouse model mimics the human model in this regard is unclear.

The possibility of unlimited donor hair

As was noted in the “Introduction” section, a major challenge to obtaining optimal hair restoration results is a lack of donor hair. In cases of marked hair loss, we often have to forego treating all areas of hair loss. Oftentimes, it is the crown that we are unable to treat, because the patient simply has a lack of donor hair.

Patients frequently inquire about the use of cloned hair. The possibility of cloning hair has been discussed for many years, but the reality has escaped us. There is good reason for this. Over the past 10 years, several genes such as WNTCitation66 and SHH,Citation67 and factors such as prostaglandins, have been identified as crucial to hair development, but the development of a hair follicles is a complex process involving multiple types of embryonal tissue. Added to this complexity, there are cellular signals that must occur at specific times to create and then induce hairs to enter into the right developmental stage at the right time. While the cloning of sheep, cow and dogs has been accomplished, we have not been able to clone human hair. A more practical way to regenerate existing miniaturized hairs or to grow completely new hairs might be the use of stem cells alone or in combination with other cell components and/or growth factors to coax the skin to produce completely new hairs.

Hairs go through various phases of cycling, including a growth phase, anagen; a transition phase called catagen, a resting phase referred to as telogen; and a stage in which the hair is expelled, termed the exogen phase. During the process, there is cell apoptosis and regeneration of tissues. Communication via cytokines and other chemical signals between the DP and pluripotent cells in the area of the hair termed the bulge area, recreate a new hair. It has been long known that dissociated cells such as mouse neonatal dermal cells and mouse neonatal epidermal cells can combine to grow hair.Citation68–Citation70 DP cells and parts of the hair follicle, such as the outer root sheath, can work together to achieve development of hairs. The majority of the studies have been done in mice or rats, and attempts to utilize these models have not translated well to humans.Citation69 Nevertheless, much has been learned about the cellular information needed to form hairs.

As early as 1984, Jahoda et alCitation71 utilized cultured DP cells along with dermal sheath cells to produce hairs. In another interesting experiment, Reynolds et alCitation72 took outer root sheath hair cells from author Jahoda’s own hair and implanted them into a co-worker. Terminal hairs developed, and when DNA analysis was performed, the hairs showed evidence of DNA from Jahoda.Citation72 Also, interestingly, there was no evidence of an immune rejection reaction as might be expected from the use of cells from different individuals.Citation72

In one mouse study, DP cells were collected and then added to bulge cells, resulting in new hair.Citation73 DP cells seem to be crucial to induction of hair growth, and one might think that you could simply inject cultured DP cells to aid in growing new hair, but in studies where DP cells are cultured, they seem to lose this inductive ability over a short time when in culture.Citation69,Citation70 Recent studies have shown that if DP cells can be cultured in a three-dimensional (3D) spherical array, the cells seem to retain the inductive ability far longer.Citation70

Work by Li et alCitation74 in 2011 has shown that human follicles could be obtained from cultured dermal and epidermal cells. The original research utilized TSC2 null fibroblasts, but subsequent work has demonstrated similar success with DP-derived fibroblasts.Citation70

Stem cells

The use of dissociated cell components and culturing methods is intriguing, and it is unclear as to what measures will need to be taken to make such methodology viable for use in humans. In the meantime, the use of stem cells may allow us to move forward more quickly in finding the means to re-grow or generate new populations of hair follicles. Most recently, a research group in California announced that they were able to use stem cells to grow human hair on a mouse.Citation75 This result has aroused great interest in as a possible answer to the issue of limited donor hair, but again, this model employed growing hair on mice. Human skin does not react exactly like mouse skin.

The use of stem cells began with embryonic cells, but due to legal and ethical concerns, researchers turned to other sources of stem cells. The discovery that stem cells exist in high quantities in adipose tissue has made such cells relatively easy to obtain.Citation68 These mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be harvested with small-volume liposuction and then separated from the co-existing fat cells. They can then be injected back into the patient in local-ized areas or can be injected systemically.Citation76 The MSCs are pluripotent, and therefore have the ability to differentiate into any type of cell. This in mind, it has been suggested that stem cells with could be injected into areas of hair loss or given intravenously to re-establish hair populations. Prior research by Festa et al has shown that adipocytes are needed to push follicular stem cell activation.Citation77

When MSCs are injected into skin, it is believed that adipocytes injected along with them die in a day or so, but create a stimulus for the MSCs to create new tissue such as fat, muscle, collagen, elastin, and other tissue types.Citation78 Presumably, inflammatory signals provide the communication for stem cells to migrate to areas of injury. Some physicians are combining stem cells with PRP, particularly when doing facial filler injections. To the author’s knowledge, no controlled studies in humans have been published demonstrating a positive effect. Much like PRP, it is unclear as to what volume should be injected, what concentration, what depth of injection, and what other stimuli are needed.

Along with the recent work by Gnedeva et al,Citation70 a study by Toyoshima et alCitation79 utilized mouse embryonal skin-derived epithelial and mesenchymal donor cells to create hair follicle germ structures. When these structures were placed into the recipient area, the hair unit, including arrector pili muscle and neural connections, also developed.

Conclusion

Hair transplant surgery has become an excellent means to treat many forms of hair loss, particularly male and female pattern hair loss. The techniques utilized today provide natural appearing results that are esthetically pleasing, but there is room for the results to be enhanced. The primary limitation has been access to sufficient quantities of donor hair. This lack of donor hair, coupled with the fact that hair loss is often progressive, has led us to encounter various challenges. The solutions to the problems we face lie in preserving donor hair, skillful surgical techniques, limiting hair loss, and developing the means to replenish hair.

Disclosure

The author is a consultant to Restoration Robotics (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and owns stock in the company. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- OkudaSThe study of clinical experiments of hair transplantationJpn J Dermatol Urol193946135

- OrentreichNAutografts in alopecias and other selected dermatological conditionsAnnals of the New York Academy of Sciences19598346347914429008

- UngerWPThe History of Hair Transplantation4th edUngerWPShapiroRNew YorkMarcel Dekker2004

- HeadingtonJTTransverse microscopic anatomy of the human scalp. A basis for morphometric approach to disorders of the hair follicleArch Dermatol19841204494566703750

- BernsteinRRassmanWSzaniawskiWHalperinAFollicular unit transplantationInt J Aesth Restor Surd19953119132

- LimmerBLElliptical strip stereoscopically assisted micrografting as an approach to further refinement in hair transplantationJ Dermatol Surg Oncol1994287897937798409

- RosePConsiderations in establishing a natural hairlineInt J Cosmet Surg199862426

- RosePTParsleyWPThe science of hair line designHaberRSStoughDBProcedures in Cosmetic Dermatology. Hair TransplantationPhiladelphiaElsevier Saunders20065572

- ShapiroRShapiroPHairline design and frontal hairline restorationFacial Plast Surg Clin North Am20132135136224017977

- NorwoodOTMale pattern baldness: classification and incidenceSouth Med J197568135913651188424

- RosePTThe trichophytic closureUngerWPShapiroRUngerRHair Transplantation5th edNew YorkInforma Healthcare Publishing2011261279

- FrechetPMinimal scars for scalp surgeryDermatol Surg2007331455517214678

- MarzolaMTrichophytic closure of the donor areaHair Transplant Forum Int2005154113116

- PuigCControlled dissection for trichophytic closure with a ledge knifeHair Transplant Forum Int2008186211

- KimDYPlaning off the inferior edge in the Frechet & Rose trichophytic closuresHair Transplant Forum Int2008186211

- ReeseRRegenerative Medicine Part 2: Use of Platelet Rich Plasma in Hair, Hair Transplant 3603LamSNew DelhiJaypee Brothers Publishing2014565573

- LacciKMDardikAPlatelet-rich plasma: support for its use in wound healingYale J Biol Med20108311920351977

- HitzigGSRegenerative medicine part 1: usage of porcine extracellular matrix in hair loss prevention, hair restoration surgery and donor scar revisionLamSHair Transplant 3603New DelhiJaypee Brothers Publishing2014553564

- BrownBLindbergKReingJStolzDBBadylakSFThe basement membrane component of biologic scaffolds derived from extracellular matrixTissue Eng20061251952616579685

- CooleyJEUse of porcine bladder matrix in hair restoration surgery applicationsHair Transplant Forum Int201137072

- PuigCUse of PRP and Dermal MatrixPresented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Cosmetic SurgeryJanuary 14; 2015New Orleans, LA Lecture

- RassmanWRBernsteinRMMcClellanRJonesRWortonEUyttendaeleHFollicular unit extraction: minimally invasive surgery for hair transplantationDermatol Surg20022872072812174065

- RosePTApproaches to FITPresented at: International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, Annual MeetingAugust 18–25, 2005Sydney, Australia Lecture

- RosePTThe use of a suction apparatus to improve healing of FUE wound sitesPresented at: International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery, Annual MeetingOctober 22–26, 2013San Francisco, CA Lecture

- RassmanWRPakJPKimJScalp micropigmentation: a useful treatment for hair lossFacial Plast Surg Clin North Am20132149750324017991

- RosePTInternal angle of hair growth versus exit angle as it relates to FUE/FITPresented at: International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery Annual Meeting2010Boston, MA Lecture

- RosePTNusbaumBRobotic hair restorationDermatol Clin2014329710724267426

- HarrisJARobotic assisted follicular unit extraction for hair restoration: case reportsCosmet Dermatol2012256284287

- WesleyCEndoscopic follicular extractionPresented at: American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery Annual MeetingJanuary 14–17, 2015New Orleans, LA Lecture

- BeehnerMLGraft survival, graft growth, and healing studiesUngerWPShapiroRHair Transplantation4th edNew YorkMarcel Dekker2004281284

- LimmerBLMicrograft survivalStoughDBHair Replacement Surgical and MedicalSt LouisMosby1996147149

- ParsleyWPPerez-MesaDReview of factors affecting the growth and survival of follicular graftsJ Cutan Aesthet Surg201032697521031063

- CooleyJEIschemia-reperfusion injury and graft storage solutionsHair Transplant Forum Int200414121139

- CooleyJEOptimal graft growthFacial Plast Surg Clin North Am20132144945524017986

- KruglugerWMoserKMoserCLaciakKHugeneckJEnhancement of in vitro hair shaft elongation in follicles stored in buffers that prevent follicle cell apoptosisDermatol Surg2004301514692918

- CooleyJEBio-Enhanced Hair RestorationHair transplant Forum International2014244121128130

- BeehnerM96-hour study of FU graft “out-of-body” survival comparing saline to hypothermosol/ATP solutionHair Transplant Forum Int20112123337

- KeeneSGorenATherapeutic hotline. Genetic variations in the androgen receptor gene and finasteride response in women with androgenetic alopecia mediated by epigeneticsDermatol Ther20112429630021410621

- DrakeLHordinskyMFiedlerVThe effect of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopeciaJ Am Acad Dermatol19994155055410495374

- KaufmanKDOlsonEAWhitingDFinasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopeciaJ Am Acad Dermatol1998395785899777765

- NusbaumAGRosePTNusbaumBPNonsurgical therapy for hair lossFacial Plast Surg Clin North Am20132133534224017975

- PriceVHMenefeeEStraussPCChanges in hair weight and hair count in men with androgenetic alopecia, after application of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil, placebo, or no treatmentJ Am Acad Dermatol1999415 Pt 171772110534633

- ThompsonIMGoodmanPJTangenCMThe influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancerN Engl J Med200334921522412824459

- AndrioleGLBostwickDGBrawleyOWthe REDUCE Study GroupEffect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancerN Engl J Med20103621192120220357281

- ZappacostaARReversal of baldness in patient receiving minoxidil for hypertensionN Engl J Med1980303148014817432414

- ShorterFFarjoNPPicksleySMRandallVAHuman hair follicles contain two forms of ATP sensitive potassium channels only one of which is switched by minoxidilFASEB J20082261725173618258787

- Blume-PeytaviULönnforsSHillmanKGarcia BartelsNA randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study to assess the efficacy of a 24-week topical treatment by latanoprost 0.1% on hair growth and pigmentation in healthy volunteers with androgenetic alopeciaJ Am Acad Dermatol201266579480021875758

- MesterESzendeBGärtnerPThe effect of laser beams on the growth of hair in miceRadiobiol Radiother (Berl)19689621626 German5732466

- MesterESpiryTSzendeBTotaJGEffect of laser rays on wound healingAm J Surg19711225325355098661

- ChungHDaiTSharmaSKHuangYYCarrollJDHamblinMRThe nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapyAnn Biomed Eng201240251653322045511

- HamblinMRDemidovaTNMechanisms of low level light therapySPIE Proc20066140112

- LeavittMCharlesGHeymanEMichaelsDHairMax LaserComb laser phototherapy device in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled, multicentre trialClin Drug Investig2009295283292

- MunckAGavazzoniMFTruebRMUse of low-level laser therapy as monotherapy or concomitant therapy for male and female androgenetic alopeciaInt J Trichology201462454925191036

- JimenezJJWikramanayakeTCBergfeldWEfficacy and safety of low-level laser device in the treatment of male and female pattern hair loss: a multicenter, randomized, sham device-controlled, double-blind studyAm J Clin Dermatol20141511512724474647

- KimHChoiJWKimJYShinJWLeeSJHuhCHLow-level light therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled multicenter trialDermatol Surg20133981177118323551662

- HamblinMMechanism of Laser-induced Hair RegrowthBostonWellman Center for Photomedicine2006 Available from http://www.photobiology.info/Hamblin.html:Biomed.laser.orgAccessed March 2, 2015

- KeeneSThe science of light biostimulation and low-level laser therapyHair Transplant Forum Int2014246201209

- GarzaLALiuYYangZProstaglandin D2 inhibits hair growth and is elevated in bald scalp of men with androgenetic alopeciaSci Transl Med20124126126ra134

- MagroCMRossiAPoeJManhas-BhutaniSSadickNThe role of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of androgenetic alopeciaJ Drugs Dermatol201110121404141122134564

- UebelCA new advance in baldness surgery with the platelet derived growth factorHair Transplant Forum Int2005153770777

- GrecoJBrandtRPreliminary experience and extended applications for the use of autologous platelet-rich plasma in hair transplantation surgeryHair Transplant Forum Int2007174131132

- LiZJChoiHIChoiDKAutologous platelet-rich plasma: a potential therapeutic tool for promoting hair growthDermatol Surg2012381040104622455565

- YankoKBrownLFDetmarMControl of hair growth and follicle size by VEGF-mediated angiogenesisJ Clin Invest2001107440941711181640

- TakikawaMNakamuraSNakamuraSEnhanced effect of platelet-rich plasma containing a new carrier on hair growthDermatol Surg201137121721172921883644

- MiaoYSunYBSunXJDuBJJiangJDHuZQPromotional effect of platelet-rich plasma on hair follicle reconstitution in vivoDermatol Surg2013391868187624118627

- LyubimovaAGarberJJUpadhyayGNeural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein modulates Wnt signaling and is required for hair follicle cycling in miceJ Clin Invest2010120244645620071778

- WooWMZhenHHOroAEShh maintains dermal papilla identity and hair morphogenesis via a Noggin-Shh regulatory loopGenes Dev201226111235124622661232

- ZhengYDuXWangWBoucherMParimooSStennKOrganogenesis from dissociated cells: generation of mature cycling hair follicles from skin-derived cellsJ Invest Dermatol2005124586787615854024

- MarshallBTIngrahamCAWuXWashenikKFuture horizons in hair restorationFacial Plast Surg Clin North Am20132152152824017993

- HigginsCAChristianoARegenerative medicine and hair loss: how hair follicle culture has advanced our understanding of treatment options for androgenetic alopeciaRegen Med20149110111124351010

- JahodaCAHorneKAOliverRFInduction of hair growth by implantation of cultured dermal papilla cellsNature198431159865605626482967

- ReynoldsAJLawrenceCCserhalmi-FriedmanPBChristianoAMJahodaCATransgender induction of hair folliclesNature19994026757333410573414

- KobayashiKNishimuraEEctopic growth of mouse whiskers from implanted lengths of plucked vibrissa folliclesJ Invest Dermatol1989922782822918234

- LiSThangapazhamRLWangJAHuman TSC-2 null fibroblast-like cells induce hair follicle neogenesis and hamartoma morphogenesisNat Commun2011223521407201

- GnedevaKVorotelyakECimadamoreFDerivation of hair-inducing cell from human pluripotent stem cellsPLoS One201510e011689225607935

- KoźlikMWójcickiPThe use of stem cells in plastic and reconstructive surgeryAdv Clin Exp Med2014231011101725618130

- FestaEFretzJBerryRAdipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cyclingCell201114676177121884937

- ComellaKUS Stem Cell Training CourseMay 1–3, 2015Sunrise, Florida, USA

- ToyoshimaKEAsakawaKIshibashiNFully functional hair follicle regeneration through the rearrangement of stem cells and their nichesNat Commun2012378422510689