Abstract

Acne is a common inflammatory disease. Scarring is an unwanted end point of acne. Both atrophic and hypertrophic scar types occur. Soft-tissue augmentation aims to improve atrophic scars. In this review, we will focus on the use of dermal fillers for acne scar improvement. Therefore, various filler types are characterized, and available data on their use in acne scar improvement are analyzed.

Introduction

Acne is a common disease. Its prevalence is ~80%.Citation1 Almost 10% of the World population are affected.Citation2 Onset of acne in most patients is during puberty, but acne among adults, especially females, is not rare.Citation3,Citation4 Scarring is an unwanted end point of the diseases and not restricted to severe disease subsets.Citation1,Citation5

For clinical trials and scoring of severity of acne scars, several algorithms have been developed. The most popular is the “Quantitative Global Scarring Grading System for Post-acne Scarring”Citation6 of which a Brazilian Portuguese version exists.Citation7 Skin picking syndrome is a differential diagnosis of acne scars with an overlap in acne excoriee.Citation8 The Quantitative Global Scarring Grading System for Postacne Scarrin” differentiates four grades: I with macular flat marks of different color; II with mild atrophic or hypertrophic scars; III with moderate atrophic or hypertrophic scars; and IV with severe atrophic or hypertrophic scars.Citation6

Acne scars

The mechanism of scarring in acne is complex. The basic inflammatory process of acne becomes more pronounced in patients with acne scarring.Citation9 This leads to an aberrant remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in pilosebaceous units of skin. Propionibacterium acnes and other gram-positive bacteria are capable to increase the formation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in sebocytes and skin fibroblasts, which may contribute to a distorted degradation of ECM.Citation10 Furthermore, peptidoglycans of gram-positive bacteria enhance the production of prostaglandin E2.Citation11

Color scarring in skin is more common and often associated with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. This can be due to genetics, pigmentation, and differences in skin care.Citation12

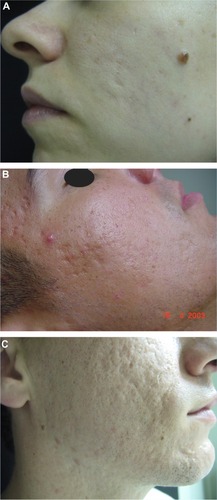

There are different clinical types of acne scars, ie, atrophic and hypertrophic scars. Atrophic scars can be further differentiated into deep and narrow icepick scars, larger rolling scars, and depressed boxcar scars (). Hypertrophic scars and acne keloids represent the hypertrophic variants.Citation13

Figure 1 Acne scars.

Acne scar management needs an effective control of inflammation, which could prevent scarring. The treatment of scars includes different approaches, namely, camouflage, peelings, microneedling, subcision, and laser therapy for atrophic scars. Hypertrophic scars may be treated by cryotherapy, corticosteroids injections, laser, and surgery.Citation13,Citation14 All procedures may improve scars but cannot establish a scar-free skin.Citation15

In this review, we will focus on the correction of ECM aberrations by the use of dermal fillers with the focus on atropic acne scars.

Dermal fillers

Dermal fillers can be classified as temporary, semipermanent, and permanent (). Although the first two classes are biodegradable with a broad range of half-lives, permanent fillers are not biodegradable.Citation16 Fillers induce a characteristic ECM response that allows a histopathological identification of various filler types.Citation17

Table 1 Dermal filler classification

Tolerability and safety of dermal filler implantation are dependent upon filler qualities, skills and knowledge of the medical doctor, and patient characteristics.Citation18–Citation20

The injection of dermal fillers to improve acne scars is based on soft-tissue augmentation. Hyaluronic acid fillers (HAFs) stimulate collagen production. A stronger stimulation of collagen production is seen with semipermanent or biostimulatory fillers, ie, poly-l-lactic acid (PLL) and calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA), and permanent fillers.Citation17

Basic knowledge of filler qualities, injection techniques, and anatomy is indispensable. Fillers should not be used in children and youngsters, in pregnant or nursing women, in patients with immune disorders, allergies against filler materials, and infections. Filler implantation warrants hygienic standards and should not be used in case of dental root procedures and skin barrier injuries to minimize the potential risk of infection. Knowledge of possible unwanted adverse effects, their prevention, and management are prerequisites.Citation21

Several injection techniques are used, such as serial punctures, linear threading, fanning and cross-hatching, deep bolus, or superficial microdroplet injections.Citation21 Cooling of the skin before and after injections reduces pain and bruising.Citation22

Dermal fillers for acne scars – clinical evidence

Silicone microdroplet injections

Medical-grade silicon has been used for a long time as a type of permanent filler in soft-tissue augmentation (). Proponents of silicon argue that the product is stable, has some antimicrobial activity, and is relatively cheap. Repeated microdroplet silicone injections are recommended with long-lasting effects.Citation23,Citation24

Table 2 Clinical trials with dermal fillers for atrophic acne scars

A 1,000 centistoke-injectable silicone emulsified with hyaluronic acid (HA; Silikone® Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA.) was used in 95 patients for tissue augmentation with only minor temporary adverse effects.Citation24 The American Society for Dermatologic Surgery listed acne scars as a possible indication for liquid silicone injections.Citation22

The 1,000 centistoke silicone oil is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved “for use as a prolonged retinal tamponade in selected cases of complicated retinal detachments where other interventions are not appropriate for patients.”Citation25 None of the silicone products are approved as soft-tissue fillers. Cosmetic filler injections have been associated with severe adverse effects, such as infection, calcifications, pneumonitis, pulmonary embolism, renal failure, and death.Citation26,Citation27 Although many of these severe complications were noted by unlicensed practitioners or lay people, the use of silicone is off-label and is not recommended by us.Citation28 Migration of silicone is another problem, leading to unwanted adverse effects.Citation29

Polymethylmethacrylate microspheres

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is an inert, synthetic permanent filler material that induces fibrous capsule formation in animals.Citation30 For cosmetic use, 20% PMMA microspheres are suspended in an aqueous solution of bovine collagen and lidocaine (Artecoll® and Artefill® Canderm Pharma, Saint Lorent, QC, Canada). Artecoll® and Artefill® have the same composition, although the microspheres are somewhat smaller in Artefill®. In the hands of experienced users, patient satisfaction with PMMA-tissue augmentation is high and the effect is long lasting.Citation31,Citation32 Most patients experience a moderate improvement.Citation33,Citation34 However, adverse effects can also be long lasting due and very nasty to the permanent nature of this filler material.Citation31

Nevertheless, in 2014, Bellafill® (previously named Artefill®) has got FDA approval “for moderate-to-severe, atrophic, distensible facial acne scars on the cheek in patients over 21 years of age.”Citation25 This makes Bellafill® the first FDA-approved medical device for correction of acne scars. The scientific background is based on the clinical trial SUN-11-001, a prospective, randomized, multicenter, and evaluator-blind study for correction facial acne scars on the cheek. Patients were randomized 2:1 for Bellafill® (n=87) or sterile saline injection.Citation46 Adult patients with Fitzpatrick skin types-I–VI were included. Data were analyzed at 6 months and after 12-month follow-up. Patients in the control group received on average higher injection volumes in primary treatment session and touch-up. Treatment-related adverse effects were noted in 14 patients with Bellafill® and in none of the control group. Bruising, injection pain, erythema, and lumpiness were observed but mild-to-moderate in 13 of the 14 patients. One case suffered from severe bruising.Citation35

Polyacrylamide

Polyacrylamide is produced by polymerization of acrylamide monomers and by cross-linking with N,N′-methylenbisacrylamide. Aquamid® is a nonabsorbable hydrogel that consists of 2.5% cross-linked polyacrylamide and 97.5% water. Although it has been extensively used for soft-tissue augmentation, no controlled trial of Aquamid® for acne scars has been identified.Citation36 Two uncontrolled trials not exclusive for patients with acne scars reported high satisfaction rates and up to 5% adverse effects, such as swelling, lumpiness, and abscess formation.Citation37,Citation38

Poly-l-lactic acid

PLL is a biodegradable, semipermanent, and biostimulatory filler stimulating fibrous tissue formation. The commercially available product (Sculptra® and Newfill® Dermik Laboratories, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) consists of PLL microparticles, sodium carboxy-methylcellulose, and mannitol. Soft-tissue augmentation may last for up to 2 years.Citation22

Two open trials and case reports recorded a significant improvement in atrophic acne scars, which may last for up to 4 years.Citation39–Citation41 Nodules developed in a single patient.Citation41 Nodule formation with PLL can be due to too superficial injection and/or inappropriate dilution. A higher dilution than used for correction of human deficiency virus-associated midfacial lipoatrophy is recommended.

Calcium hydroxylapatite

CaHA is a synthetic, biodegradable, semipermanent, and biostimulatory filler. The commercially available product (Radiesse® Merz Pharma, Frankfurt, Germany) contains 30% CaHA microparticles suspended in a carboxy-methylcellulose gel. CaHA stimulates collage production. Soft-tissue augmentation lasts for up to 18 months.Citation42 Open trials reported improvement in boxcar scars but failure in icepick scars, suggesting for a combination of CaHA with subcision for better outcome.Citation43,Citation44

Collagen

Collagen fillers are temporary fillers of either bovine, porcine, or recombinant human origin. The predominant collagen is collagen I as in human dermis. For bovine collagen fillers (Zyderm® I and II, INAME Aesthetics, Santa Barbara, CA, USA), two intradermal skin tests 2–4 weeks apart are recommended due to its allergenic potential. The skin test is not necessary for porcine collagen (Evolence® ColBar LifeScience, Herzliya, Israel) or recombinant human collagen (Cosmoderm® and Cosmoplast® Allergan, Dublin, Ireland). Collagen fillers should not be used in patients with autoimmune diseases or collagen hypersensitivity. Soft-tissue augmentation usually persists up to 6 months.Citation45–Citation47 The use of collagen fillers for atrophic acne scars was recommended by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.Citation22

A case report suggested that in some patients, the effect may persist for at least 12 months.Citation48

Hyaluronic acid filler

HA is a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide and a physiologic component of ECM. Natural HA has the disadvantage of a short half-life of 12 hours only. Therefore, various technologies for cross-linking have been developed to stabilize HAF. Linking agents include 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether, divinyl sulfone (DVS), and 2,7,8-diepoxyoctane. Modern HAFs are produced by bacterial fermentation. HAF can be divided into mono- (Esthelis® Anthies, Geneva, Switzerland/Belotero® Merz Pharma, Frankfurt, Germany, Juvederm® Allergan, Dublin, Ireland, etc) or biphasic (Perlane®, Restylane® Galderma, Sophia Anitpolis, France), whereas biphasic fillers contain HA particles suspended in HA gel.Citation18

HAFs differ in their cross-linking technology, percentage of cross-linking, the amount of HA and bound water, viscosity, hardness, cohesivity, HA concentration, gel-to-fluid ratio, degree of HA modification, swelling, modulus, particle size (for biphasic HAF), ease of injection, and approved indications.Citation49 This allows tailored treatment of various conditions. Injection of HAF stimulates collagen production by fibroblasts contributing to soft-tissue augmentation.Citation50

Open trials suggest a high treatment satisfaction of patients. Most common adverse effects were mild transitory erythema and mild-to-moderate pain during injection.Citation51,Citation52 Pneumatic injection of HA was used in two patients to improve acne scars by one grade.Citation53 HAF offers the opportunity of a rapid correction of nodules, etc, by the use of hyaluronidase injection.Citation54

Comparison with other treatments for atrophic acne scars

All treatments for acne scar aim not to cure but to make the scars less visible. Among surgical procedures, subcision and microneedling are the most popular with good efficacy in atrophic acne scars except icepick scars. Punch techniques may be used for icepick scars.Citation55 Ablative lasers, such as CO2 or erbium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Er: YAG), are effective in atrophic acne scars. Ablative fractional lasers have also been investigated and demonstrated an improved risk profile. Multiple treatments are necessary in case of deep scars. Nonablative lasers may be used in mild acne scarring as an alternative. Laser treatments are relatively expensive and have their own risks, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation – particularly in ethnic skin – and scarring.Citation56

Deep peels with trichloroacetic acid alone or in combination with other peels or microneedling can improve atrophic scars. Repeated treatments may be necessary depending on the depth of the scars. A 100% trichloroacetic acid peel is capable to improve even icepick scars.Citation57

Other techniques have been developed, but clinical data of controlled trials are missing.

Conclusion and outlook

Dermal fillers belong to the armamentarium to improve acne scars. Their capability to augment soft tissue is the most obvious advantage. Tolerability, durability of the augmentation, adverse effects, and risk profiles differ between the various dermal filler types. Permanent fillers may exert very long-lasting effects, but in case of unwanted adverse effects, the complete removal of the material may be necessary. Temporary fillers need repeated treatments increasing the costs. HAFs have been shown to improve skin quality over time. Semipermanent fillers seem to be a good alternative. For safety reasons, deep injections are recommended.

When should dermal fillers be considered? Dermal fillers may be appropriate in soft atrophic scars of the rolling or boxcar type. HAF can improve the quality of overlying skin. Dermal fillers can be used either alone or in combinations with other procedures such as subcision, microneedling, ablative or fractional lasers, and peels. Although the use of dermal fillers is widespread, not much controlled studies have been published on their use in acne scars. Most data are from case reports and uncontrolled studies. The outcome and longevity of the tissue augmentation depend not only on the filler type and injection technique but also on the scar type. Best results have been obtained for rolling scars and depressed boxcar scars. In contrast, icepick scars and hypertrophic scars or acne keloids will not benefit from dermal filler injections at all. In practice, a multimodal approach seems to fulfill patient’s expectation at best.Citation55,Citation58

Fillers that can modulate ECM to reduce scarring seem to be the most interesting for future developments of a targeted treatment. Based on the experience with midfacial soft-tissue augmentation, targeted activation of white adipose tissue stem cells could be a prospective in filler use.Citation59 Animal studies provide evidence that the combination of HA and stem cells leads to better and more stable results in tissue augmentation.Citation60,Citation61 This could be a step forward in tissue regeneration from which patients with acne scars may benefit in the future.

Author contributions

UW and AG conceived and designed the review, analyzed the data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, agreed with the manuscript results and conclusions, jointly developed the structure and arguments for the article, and made critical revisions and approved final version. Both the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics

As a requirement of publication, authors have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality, and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects.

The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DrénoBRecent data on epidemiology of acneAnn Dermatol Venereol2010137Suppl 2S49S5121095494

- TanJKBhateKA global perspective on the epidemiology of acneBr J Dermatol2015172Suppl 131225597339

- ParkSYKwonHHMinSYoonJYSuhDHEpidemiology and risk factors of childhood acne in Korea: a cross-sectional community based studyClin Exp Dermatol Epub2015525

- HolzmannRShakeryKPostadolescent acne in femalesSkin Pharmacol Physiol201427Suppl 13824280643

- ZouboulisCCBettoliVManagement of severe acneBr J Dermatol2015172Suppl 1273625597508

- GoodmanGJBaronJAPostacne scarring – a quantitative global scarring grading systemJ Cosmet Dermatol20065485217173571

- CachafeiroTHEscobarGFMaldonadoGCestariTFTranslation into Brazilian Portuguese and validation of the “quantitative global scarring grading system for post-acne scarring”An Bras Dermatol201489585185325184939

- KimDIGarrisonRCThompsonGA near fatal case of pathological skin pickingAm J Case Rep20131428428723919102

- SatoTKuriharaHAkimotoNNoguchiNSasatsuMItoAAugmentation of gene expression and production of promatrix metalloproteinase 2 by Propionibacterium acnes-derived factors in hamster sebocytes and dermal fibroblasts: a possible mechanism for acne scarringBiol Pharm Bull201134229529921415544

- SatoTShiraneTNoguchiNSasatsuMItoANovel anti-acne actions of nadifloxacin and clindamycin that inhibit the production of sebum, prostaglandin E(2) and promatrix metalloproteinase-2 in hamster sebocytesJ Dermatol201239977478022394009

- HollandDBJeremyAHTRobertsSGSeukeranDCLaytonAMCunliffeWJInflammation in acne scarring: a comparison of the responses in lesions from patients prone and not prone to scarBr J Dermatol20041501728114746619

- DavisECCallenderVDA review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategiesJ Clin Aesthet Dermatol201034243820725545

- FabbrociniGAnnunziataMCD’ArcoVAcne scars: pathogenesis, classification and treatmentDermatol Res Pract2010201089308020981308

- JansenTPoddaMTherapy of acne scarsJ Dtsch Dermatol Ges20108Suppl 1S81S8820482696

- NastADrénoBBettoliVEuropean dermatology forum. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acneJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201226Suppl 112922356611

- AhnCSRaoBKThe life cycles and biological end pathways of dermal fillersJ Cosmet Dermatol201413321222325196689

- MercerSEKleinermanRGoldenbergGEmanuelPOHistopathologic identification of dermal filler agentsJ Drugs Dermatol2010991072107820865837

- WollinaUGoldmanADermal fillers: facts and controversiesClin Dermatol201331673173624160278

- ZielkeHWölberLWiestLRzanyBRisk profiles of different injectable fillers: results from the injectable filler safety study (IFS Study)Dermatol Surg200734111018053058

- CohenJLUnderstanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complicationsDermatol Surg200834Suppl 1S92S9918547189

- AlamMGladstoneHKramerEMAmerican Society for Dermatologic SurgeryASDS guidelines of care: injectable fillersDermatol Surg200834Suppl 1S115S14818547175

- De BoulleKHeydenrychIPatient factors influencing dermal filler complications: prevention, assessment, and treatmentClin Cosmet Investig Dermatol20158205214

- BarnettJGBarnettCRTreatment of acne scars with liquid silicone injections: 30-year perspectiveDermatol Surg20053111 pt 21542154916416636

- FultonJCapertonCThe optimal filler: immediate and long-term results with emulsified silicone (1,000 centistokes) with cross-linked hyaluronic acidJ Drugs Dermatol201211111336134123135085

- FDAFederal register19986318788 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/010298a.txtAccessed July 25, 2015

- LeeJHChoiHJRare complication of silicone fluid injection presenting as multiple calcification and skin defect in both legs: a case reportInt J Low Extrem Wounds2015141959725564484

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Acute renal failure associated with cosmetic soft-tissue filler injections – North Carolina, 2007MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2008571745345618451755

- WollinaUSilicone injectionsJ Cutan Aesthet Surg20125319723112517

- ChoiHJPseudocyst of the neck after facial augmentation with liquid silicone injectionJ Craniofac Surg2014255e474e47525148641

- LemperleGOttHCharrierUHeckerJLemperleMPMMA microspheres for intradermal implantation: Part I. Animal researchAnn Plast Surg199126157631994814

- BagalADahiyaRTsaiVAdamsonPAClinical experience with polymethylmethacrylate microspheres (Artecoll) for soft-tissue augmentation: a retrospective reviewArch Facial Plast Surg20079427528017638763

- Carvalho CostaIMSalaroCPCostaMCPolymethylmethacrylate facial implant: a successful personal experience in Brazil for more than 9 yearsDermatol Surg20093581221122719438669

- EpsteinRESpencerJMCorrection of atrophic scars with artefill: an open-label pilot studyJ Drugs Dermatol2010991062106420865835

- KarnikJBaumannLBruceSA double-blind, randomized, multicenter, controlled trial of suspended polymethylmethacrylate microspheres for the correction of atrophic facial acne scarsJ Am Acad Dermatol2014711778324725475

- FDAUS Food and Drug Administration2014 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf2/P020012S009b.pdfAccessed June 27, 2015

- YamauchiPSEmerging permanent filler technologies: focus on AquamidClin Cosmet Investig Dermatol20147261266

- von BuelowSvon HeimburgDPalluaNEfficacy and safety of polyacrylamide hydrogel for facial soft-tissue augmentationPlast Reconstr Surg200511641137114616163108

- Kalantar-HormoziAMozafariNRastiMAdverse effects after use of polyacrylamide gel as a facial soft tissue fillerAesthet Surg J200828213914219083518

- BeerKA single-center, open-label study on the use of injectable poly-l-lactic acid for the treatment of moderate to severe scarring from acne or varicellaDermatol Surg200733Suppl 2S159S16718086054

- SadoveRInjectable poly-l-lactic acid: a novel sculpting agent for the treatment of dermal fat atrophy after severe acneAesthetic Plast Surg200933111311618923863

- SapraSStewartJAMraudKSchuppRA Canadian study of the use of poly-l-lactic acid dermal implant for the treatment of hill and valley acne scarringDermatol Surg201541558759425915626

- JacovellaPFUse of calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) for facial augmentationClin Interv Aging20083116117418488886

- GoldbergDJAminSHussainMAcne scar correction using calcium hydroxylapatite in a carrier-based gelJ Cosmet Laser Ther20068313413616971362

- TreacyPTreatment of Acne Scars with RadiesseLondonAesthetic Medicine2008

- ElsonMLClinical assessment of Zyplast implant: a year of experience for soft tissue contour correctionJ Am Acad Dermatol1988184 pt 17077133372763

- VarnavidesCKForsterRACunliffeWJThe role of bovine collagen in the treatment of acne scarsBr J Dermatol198711621992062950913

- SageRJLopiccoloMCLiuAMahmoudBHTierneyEPKoubaDJSubcuticular incision versus naturally sourced porcine collagen filler for acne scars: a randomized split-face comparisonDermatol Surg201137442643121388487

- SmithKCRepair of acne scars with Dermicol-P35Aesthet Surg J2009293 SupplS16S1819577176

- WollinaUGoldmanAHyaluronic acid dermal fillers: safety and efficacy for the treatment of wrinkles, aging skin, body sculpturing and medical conditionsClin Med Rev Ther20113107121

- TurlierVDelalleauACasasCAssociation between collagen production and mechanical stretching in dermal extracellular matrix: in vivo effect of cross-linked hyaluronic acid filler. A randomised, placebo-controlled studyJ Dermatol Sci201369318719423340440

- HassonARomeroWATreatment of facial atrophic scars with Esthélis, a hyaluronic acid filler with polydense cohesive matrix (CPM)J Drugs Dermatol20109121507150921120258

- HalachmiSBen AmitaiDLapidothMTreatment of acne scars with hyaluronic acid: an improved approachJ Drugs Dermatol2013127e121e12323884503

- PatelTTevetOEffective treatment of acne scars using pneumatic injection of hyaluronic acidJ Drugs Dermatol2015141747625607911

- RzanyBBecker-WegerichPBachmannFErdmannRWollinaUHyaluronidase in the correction of hyaluronic acid-based fillers: a review and a recommendation for useJ Cosmet Dermatol20098431732319958438

- GozaliMVZhouBEffective treatments of atrophic acne scarsJ Clin Aesthet Dermatol201585334026029333

- SobankoJFAlsterTSManagement of acne scarring, part I: a comparative review of laser surgical approachesAm J Clin Dermatol201213531933022612738

- HessionMTGraberEMAtrophic acne scarring: a review of treatment optionsJ Clin Aesthet Dermatol201581505825610524

- O’DanielTGMultimodal management of atrophic acne scarring in the aging faceAesthetic Plast Surg20113561143115021491169

- WollinaUMidfacial rejuvenation by hyaluronic acid fillers and subcutaneous adipose tissue – a new conceptMed Hypotheses201584432733025665858

- NowackiMPietkunKPokrywczyńskaMFilling effects, persistence, and safety of dermal fillers formulated with stem cells in an animal modelAesthet Surg J20143481261126925168156

- HuangSHLinYNLeeSSNew adipose tissue formation by human adipose-derived stem cells with hyaluronic acid gel in immunodeficient miceInt J Med Sci201512215416225589892