Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic progressive liver disease characterized by high levels of aminotransferases and autoantibodies, hypergammaglobulinemia, and interface hepatitis. AIH affects all races and all ages worldwide, regardless of sex, although a preponderance of females is a constant finding. The etiology of AIH has not been completely elucidated, but immunogenetic background and environmental parameters may contribute to its development. The most important genetic factor is human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), especially HLA-DR, whereas the role of environmental factors is not completely understood. Immunologically, disruption of the immune tolerance to autologous liver antigens may be a trigger of AIH. The diagnosis of classical AIH is fairly easy, though not without pitfalls. In contrast, the diagnosis of atypical AIH poses great challenges. There is confusion as to the definition of the disease entity and its boundaries in the diagnosis of overlap syndrome, drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis, and AIH with concomitant nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or chronic hepatitis C. Centrilobular zonal necrosis is now included in the histological spectrum of AIH. However, the definition and the significance of AIH presenting with centrilobular zonal necrosis have not been examined extensively. In ~20% of AIH patients who are treated for the first time with standard therapy, remission is not achieved. The development of more effective and better tolerated novel therapies is an urgent need. In this review, we discuss the current challenges and the future prospects in relation to the diagnosis and treatment of AIH, which have been attracting considerable recent attention.

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) was described for the first time early in the 1950s, under the name of lupoid hepatitis, as a disease prone to afflicting young women.Citation1 Since then, the boundaries of AIH have expanded to all races and to all ages.Citation2,Citation3 The clinical presentations of AIH at the time of diagnosis vary considerably, from acute liver failure (ALF) or acute hepatitis, which are relatively rare, to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma, which represent the primary diagnosis in ~60% of patients.Citation4 This may indicate that the majority of AIH cases tend to progress insidiously. AIH is classified as type 1 or type 2, according to differences in their autoantibodies. Type 1 is the major type of AIH and presents with antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and/or antismooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs), whereas the less common type 2 AIH is characterized by antiliver kidney microsome 1 (LKM 1). The titer of LKM is associated with disease activity of type 2 AIH.Citation5 Adult type 1 and type 2 AIHs share similar profiles with respect to clinical, biochemical, and histological features, and genetic predisposition.Citation6

The variety of clinicopathological features of AIH may be partly due to differences in immunogenetic background.Citation7 The immunological mechanism of AIH is considered to be an abnormal T lymphocyte reaction to autologous hepatocytes,Citation8 caused by a failure of immunological tolerance. The diagnosis of classical AIH is fairly easy after exclusion of other known liver diseases. Nowadays, the definition and the diagnostic procedure for significant liver diseases other than AIH are firmly established. Though revised international diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) have been widely used for the diagnosis of AIH, the gold standard for diagnosis is an empiric judgment by an experienced hepatologist. The IAIHG criteria are based on the clinical, biochemical, serological, and histological characteristics of AIH and the response to immunosuppressive therapy.Citation9 It may be beneficial to form an objective judgment as to the probability of AIH. However, the diagnostic criteria are not necessarily reliable for the diagnosis of atypical AIH, including acute onset AIH, overlap syndrome,Citation10 drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis (DIAIH), and AIH coincident with other liver diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Histologically, centrilobular zonal necrosis (CZN) is recognized as part of the spectrum of AIH.Citation11

In the treatment of AIH, corticosteroids alone or combined with azathioprine are standard.Citation12 Remission can be achieved in ~80% of AIH patients who are treated by standard therapy. In the case of poor response or intolerance, alternative immunosuppressive therapy should be introduced. Mycophenolate mofetil may become a first-line drug as a replacement for azathioprine.Citation13 In the future, novel drugs that can act specifically on the immune mechanisms of AIH will be developed.

Recent rapid progress in antiviral drugs against hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B may eradicate viral hepatitis in the near future. AIH will then attract increasing attention as one of the major issues in the area of hepatology. In this review, the current challenges and future prospects of AIH are discussed from the viewpoint of immunopathophysiology (immunogenetic background and immune mechanisms), diagnosis, and treatment.

Immunogenetic background of AIH

The close association between AIH and human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) has been recognized in CaucasianCitation14 (HLA-DR3 and DR4) and JapaneseCitation15 (HLA-DR4) patients. As an immunogenetic factor other than HLA, the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) +49 A/G polymorphism may be associated with a susceptibility to AIH.Citation16 However, a recent genome-wide association study of genetic susceptibility to AIH showed a strong association only between the HLA locus and AIH, while dozens of weak susceptibility loci were determined.Citation17 Therefore, the impact of the CTLA-4 polymorphism may be considerably limited.

In Latin Americans, DRB1*1301 is correlated with susceptibility to type 1 AIH.Citation18 DRB1*1301 is also correlated with child type 1 AIH in Germany.Citation19 In Pakistan, HLA-DR6, DRB1*14, and DRB1*13 were more prevalent in AIH.Citation20

HLA may affect not only disease susceptibility but also the clinical manifestations and outcome of AIH. In Japan, HLA-DR4 is related to higher levels of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG), the appearance of ASMA,Citation21 and age at the onset of AIH. HLA-DR4 is less frequent in childhood or advanced age (>70 years).Citation22 In Caucasians, HLA-DR4 is associated with less severity and older age at onset compared to HLA-DR3. In addition, patients with HLA-DR3 may have more progressive disease than those with DR4. Similarly, HLA-DRB1*0301 and DRB1*0401 alleles are both independently associated with the aggregate diagnostic IAIHG score in type 1 AIH patients, and HLA-DRB1*0301 strongly influences the severity of AIH.Citation23

The association between the HLA-DR or HLA-DRB1 allele and AIH is widely accepted. However, another locus of HLA (A, B, C, or DQ) may be closely associated with AIH. As there is a strong linkage disequilibrium in the HLA locus, it has been claimed that the haplotype of HLA is more closely involved in susceptibility to AIH and more strongly modifies the clinical manifestations of type 1 AIH.Citation7 Meanwhile, the immunogenetic background of type 2 AIH has not been extensively studied, because of the relatively small number of patients. A possible relation between HLA-DQB1*0201, HLA-DRB1*07, or HLA-DRB1*03 and type 2 AIH has been reported.Citation24 A future, large-scale study will be needed to distinguish the differences in immunogenetic background between type 2 and type 1 AIHs.

The significance of HLA in the onset and progression of AIH should be examined worldwide, because the distribution of HLA in the background population is different among different races. This may indicate that the type of HLA involved in the susceptibility to AIH and its progression is different in different races. The clinical characteristics of type 1 AIH in Asia and in European or American countries show some differences, in the age at onset and the prevalence of advanced liver disease. Differences in immunogenetic backgrounds may be related to the differences in clinical presentation.Citation25 In Asian countries, the clinical features of AIH in India and Pakistan are reported to differ considerably from those in East Asia. A high prevalence of advanced liver disease at first diagnosis and a poor outcome of AIH were the features of AIH in India and Pakistan. The differences may be attributed to differences in HLA.

Immunological mechanisms participating in the onset and persistence of AIH

Although the factors triggering the onset of AIH have not been clearly identified, AIH is considered to be initiated by an immunological reaction against autologous liver antigens.Citation26–Citation28 Presumably, an epitope of liver autoantigen binds with the paratope of an HLA class II antigen and is exhibited on the surface of antigen-presenting cells. Nevertheless, the immune reaction to autoantigens is not evoked under normal conditions, because of immune tolerance; autoantigens can be recognized by naive CD4-positive T cells. Once a liver autoantigen is recognized via costimulatory signals, naive T cells are activated and the immune reaction is initiated. Naive T cells can be activated and differentiated into Th1, Th2, or Th17 cells, depending on the immunological microenvironment and the nature of the antigen epitope. These T cells then begin to trigger immune cascades.

Cytokines secreted from differentiated T cells are the key molecules for triggering immune reactions. Interferon-gamma, which is mainly produced by Th1 cells, may play a central role in liver cell damage by stimulating CD8-positive cells and enhancing the expression of HLA class I and class II molecules. Tumor necrosis factor alpha, secreted from activated macrophages, may be a key cytokine in the occurrence of inflammatory disease. Interleukin (IL)-4, which is secreted by Th2 cells, is a major cytokine for the maturation of B cells into plasma cells, which leads to the production of autoantibodies. Th17 is differentiated under the stimulation of both transforming growth factor beta and IL-6. Excessive Th17 cells are considered to be a major cause of autoimmune diseases. IL-23 is involved in the maintenance of Th17 cells and thus may play a role in AIH. Th17 cells secrete IL-17 and suppress regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tregs are essential for maintaining the homeostasis of the immune system and suppress excessive immune reactions in autoimmune diseases. Although the issue is still controversial,Citation29 defective Tregs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AIH,Citation30 triggering its onset and persistence.

Pitfalls in the diagnosis of classical AIH

Although the diagnosis of classical AIH is not difficult, several potential pitfalls need to be taken into account. First of all, the presence of ANA should not be overemphasized. ANA is a nondisease-specific autoantibody and is frequently detected in the sera of chronic liver diseases other than AIH. A low or middle titer of ANA is not decisive in the differential diagnosis. In some particular cases, a high titration of ANA may be found in non-AIH patients. Similarly, prominent hypergammaglobulinemia and/or high serum IgG may be found in non-AIH chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Moreover, the level of transaminases may not indicate the severity of interface hepatitis. Some AIH patients with slight elevation of transaminases may have severe interface hepatitis in liver histology. Contrarily, in a few patients who exhibited hypergammaglobulinemia, a high titer of ANA, and significant elevation of transaminases, necroinflammatory change was not observed in liver histology. Therefore, liver biopsy is essential for establishing the diagnosis of AIH. It should be kept in mind that CZN is part of the histological spectrum of AIH, even if interface hepatitis is not observed.Citation11 Thus, a liver biopsy may provide essential information regarding the diagnosis of AIH.

Another important issue in the diagnosis of AIH is exclusion of known etiologies of liver diseases other than AIH, because not only the laboratory findings but also the histological features of AIH may largely resemble those of other chronic liver diseases, including drug-induced liver injury (DILI), chronic viral hepatitis, and other known chronic liver diseases. Among these, chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection (CAEBV) must be carefully distinguished from AIH. Although there is a report of AIH being induced in a patient with preexisting CAEBV and successfully treated with a corticosteroid,Citation31 CAEBV is generally a life-threatening progressive disease if adequate management is neglected. In some cases of CAEBV, the clinical, laboratory, and histological features are quite similar to those of AIH, but the prognosis is extremely poor.Citation32,Citation33 CAEBV should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients who do not respond sufficiently to immunosuppressive therapy. All AIH patients who exhibit an unusual clinical course should be thoroughly reexamined for the possibility of other liver disease.

Diagnosis and management of atypical AIH

Overlap syndrome

The concept of overlap syndrome applies to patients who present the features of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) along with the features of AIH. PBC-AIH or PSC-AIH overlap syndrome denotes a condition in which the primary (dominant) disorder is PBC or PSC, and the features of AIH are defined concomitantly. In other words, a small number of PBC or PSC patients present the clinicopathological features of AIH, including high levels of IgG, positivity of ANA/ASMA, a prominent increase in transaminases, and interface hepatitis in liver histology, at the time of first diagnosis or during the treatment of PBC or PSC. However, there is no objective standard by which to judge whether PBC/PSC or AIH is the dominant disease in the same patient.

The overlap syndrome is conceptually divided into four categories (). The majority of overlap syndrome cases are considered to be PBC-AIH overlap. It is a debatable issue whether PBC-AIH overlap is a distinctive disease entity or only a variant form of PBC. ANA is frequently detectable in PBC patients.Citation36 In the liver pathology of PBC, mild to moderate interface hepatitis is not an uncommon feature.Citation37 Thus, the distinctive differentiation between a variant form of PBC (PBC exhibiting active hepatitis) and PBC-AIH overlap syndrome is rather uncertain. Nonetheless, prominent active hepatitis and the features of AIH can be seen in patients with PBC, though such a condition is rare.

Table 1 Classification of overlap syndrome

The Paris criteria are often applied to the definition of PBC-AIH overlap syndrome,Citation38 though these are not universally established. In the Paris criteria, two of three features associated with AIH are required in addition to two of three features related to PBC: for AIH, a serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level ≥5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), an IgG level ≥2 times the ULN, or the presence of ANA or ASMA and interface hepatitis on liver biopsy; for PBC, a serum alkaline phosphatase level ≥2 times the ULN or a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level ≥5 times the ULN, the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies, and florid duct lesions or destructive cholangitis on liver histology. In any case, distinctive clinical, laboratory, and pathological features of AIH on top of a definitive diagnosis of PBC are required for the diagnosis of PBC-AIH overlap.

PBC with marked elevation of transaminases has been treated empirically with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) combined with a short-duration corticosteroid. From the viewpoint of the management of PBC-AIH overlap, the results of a meta-analysis suggested that the combination of corticosteroid and UDCA is a first-line therapy, because the combination therapy was more effective than UDCA alone.Citation39 However, the efficacy of UDCA alone may depend on the histological severity of the interface hepatitis in PBC patients with features of AIH. The efficacy of UDCA alone and in combination therapy is similar in patients with low to moderate interface hepatitis, whereas the efficacy of UDCA alone is significantly lower than that of combined therapy in patients with severe interface hepatitis. Thus, UDCA alone is the treatment of choice in mild to moderate interface hepatitis, whereas UDCA combined with a corticosteroid should be preferred for the treatment of severe interface hepatitis.Citation40 It would be interesting to know whether withdrawal of the corticosteroid exacerbates the liver inflammation in PBC-AIH overlap patients who are exhibiting prominent interface hepatitis. A high frequency of exacerbation after the withdrawal of a corticosteroid could denote the existence of PBC-AIH overlap in the true sense of overlapping disease. In our experience, corticosteroids may be successfully discontinued without any flare-up of transaminases in these patients.

There are no guidelines for the diagnosis of other types of overlap syndrome. A high prevalence of PSC-AIH overlap syndrome has been noted among PSC patients.Citation41 Long-term follow-up of patients treated with UDCA, or UDCA plus an immunosuppressive drug, indicated that the prognosis of PSC-AIH overlap is not worse than that of classical PSC.Citation42

The diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap should be viewed carefully. Bile duct injury or bile duct reaction is a common histopathological feature of AIH.Citation43 The interlobular bile duct may be frequently affected and damaged by an intensive portal inflammation of AIH. Nevertheless, a typical PBC bile duct lesion is very hard to find in the liver tissue of AIH. Therefore, an easy diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap based on the histological finding of bile duct injury should be strictly resisted.

DIAIH

The diagnosis of DIAIH is relatively easy if the particular drug that is known to be the cause of DIAIH is administered until the onset of AIH. Minocycline, nitrofurantoin, methyldopa, hydralazine, and herbal drugs are the major drugs closely associated with DIAIH.Citation44 In addition, statinsCitation45 and other newly developed drugs are reported to be associated with DIAIH. Statins tend to be taken by many patients for long periods, as opposed to minocycline and nitrofurantoin. Nevertheless, the reported number of DIAIH cases caused by statins is fairly small. Statins are often given to middle-aged or elderly people who are susceptible to AIH. Therefore, it should be borne in mind that the onset of AIH may incidentally coincide with the use of statins. AIH appearing during statin use must be carefully investigated to determine whether it was induced by the statin or not.

DILI can be distinguished from AIH without difficulty.Citation46 However, the clinical and histopathological features of DIAIH are sometimes quite similar to those of AIH.Citation47 Response to corticosteroids is similar for both DIAIH and AIH.Citation48 There is disagreement as to whether recurrence after discontinuation of corticosteroids occurs in DIAIH. In DIAIH, successful discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy has been reported, without relapses.Citation44 Contrarily, the rate of relapse has been reported by others to be similar for both idiopathic AIH and DIAIH.Citation48 It must be noted that, the latter report included a significant number of statin-induced DIAIH cases, while patients with nitrofurantoin-induced DIAIH are less likely to relapse than other DIAIH patients after discontinuation of immunosuppression. This finding may raise the suspicion that most statin-induced DIAIH is not drug-induced disease but idiopathic AIH, which appeared incidentally during statin use. In any case, long-term follow-up of patients who are diagnosed with DIAIH is recommended to monitor any relapse.

AIH-like laboratory findings are found in a majority of cases of nitrofurantoin- or minocycline-induced liver injury and in about half the cases of methyldopa- or hydralazine-induced liver injury. This abnormality spontaneously improves with recovery from liver damage and is not associated with HLA-DR3 or DR4.Citation49 Therefore, the immunopathological settings of DIAIH are quite different from those of idiopathic AIH. Although the pathogenesis of DIAIH has not been completely elucidated, studies of dihydralazine and tienilic acid (these drugs are not currently used) suggested that bonding of reactive drug metabolites and cellular proteins forms neoantigens that can be recognized by immune systems, and that immune reactions against neoantigens may induce DIAIH.Citation50

Under the present circumstances, the diagnosis of DIAIH is left to personal subjective judgment. The establishment of objective diagnostic criteria for DIAIH is urgently required.

AIH accompanied by NAFLD and chronic hepatitis C (CHC)

AIH and coincident NAFLD is not a rare condition. Patients with coincident AIH and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are more likely to present with cirrhosis and more likely to develop an adverse clinical outcome with poorer survival compared to AIH without coincidence of NAFLD/NASH.Citation51 This finding suggests that the simultaneous presence of AIH and NASH may confer an increased risk of progressive liver disease and death. This hypothesis is supported by the finding from a mouse model that preexisting NAFLD potentiates the severity of AIH.Citation52 In patients with NAFLD/NASH, a high prevalence of ANA and ASMA has been noted.Citation53 Therefore, liver biopsy is essential for the definition of AIH and coincident NAFLD/NASH. Generally, the histological features of NASH are quite different from those of AIH and coincident NASH. However, AIH with coincident NASH is sometimes very hard to distinguish from NASH, even after inspection of liver histology. In addition, the response to standard therapy for AIH does not always become the index of the diagnosis of AIH coincident with NASH. Corticosteroids may exaggerate the deposition of fat in hepatocytes and worsen NASH, while reducing the inflammatory activity of AIH. Therefore, the efficacy of corticosteroids in AIH and coincident NASH may be attenuated. Close surveillance of these patients is warranted; if remission is not achieved using standard therapy, the corticosteroid must be replaced by other immunosuppressive drugs.

In CHC, autoimmune phenomena are often found. ANA is present in ~30% of patients with CHC.Citation54 LKM antibodies are found in some patients with CHC.Citation55 In general, molecular mimicry could explain the positivity of LKM antibodies in patients with HCV infection.Citation56 The autoantibody status is not useful for differentiating between CHC alone and AIH concurrent with CHC. The diagnosis of concurrent AIH and HCV infection may depend on the empiric judgment of an experienced hepatologist, because there are no diagnostic criteria. Although the revised diagnostic criteria are not intended to be used for the diagnosis of AIH and coincident CHC, the criteria may be useful to some degree in the differential diagnosis.Citation57

Liver histology may play a role in the definition of AIH and coincident CHC. The liver pathology of autoimmune-predominant CHC cases exhibits histological characteristics of AIH: severe interface hepatitis, plasma cell infiltration, and extensive lymphocyte accumulation in the portal region. However, these findings may also be seen in CHC without coincident AIH. Therefore, the diagnosis of AIH coincident with CHC is fairly ambiguous. As AIH with coincident CHC is not a familiar condition, an easy diagnosis should be strictly resisted.

Most CHC patients are successfully treated by a rapidly progressing interferon-free regimen against HCV infection. It would be very interesting to know whether liver inflammation completely subsides after the elimination of HCV and whether relapse occurs after the discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with AIH and coincident CHC.

Histologically atypical AIH: CZN

The most significant pathological feature of classical AIH is interface hepatitis, in which hepatocytes in the periportal zone are affected. In contrast, confluent necroinflammatory change in the centrilobular zone (zone 3) may be seen in histologically atypical AIH. The necroinflammatory change in zone 3 is called CZN, centrilobular (central) necrosis, or zone 3 necrosis. The characteristics of histologically atypical AIH were first reported using the name CZN and included marked confluent necrosis in zone 3 with relative sparing of the portal area.Citation58 Subsequently, pathological changes in zone 3 have been described by many authors. However, the nomenclature and the definition of necroinflammatory changes in zone 3 are confused; thus, the significance of CZN has not been correctly evaluated.

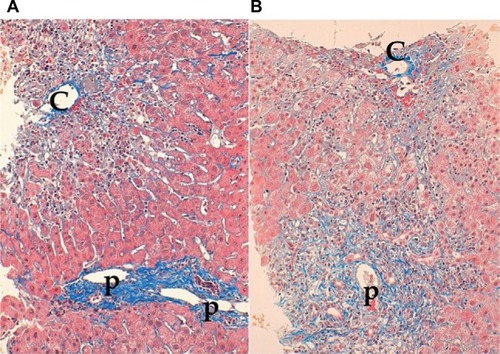

Though some authors described significant but mild to moderate necroinflammation in zone 3 as zone 3 necrosis,Citation59 these findings are frequently encountered in histologically typical AIH, especially in patients with significant lobular hepatitis and those with slight fibrosis. In contrast, others have described CZN as marked confluent necrosis in zone 3 with sparing of the portal area.Citation60 However, typical CZN and significant interface hepatitis may coexist in the same sample of a liver biopsy.Citation61 Therefore, histologically atypical AIH may be classified into two types: CZN with sparing interface hepatitis and CZN with significant interface hepatitis ().

Figure 1 Two types of centrilobular zonal necrosis (CZN).

The idea that CZN may represent a very early histologic phenotype of typical AIH is derived from a case report in which a marked predominance of centrizonal injury in an initial liver biopsy was later transformed to a typical histological appearance over the course of several months.Citation62 However, CZN can be found in the liver biopsies of patients who developed AIH >6 months earlier. In addition, CZN may coexist with significant portal fibrosis in chronic AIH. Histologically atypical AIH in Japanese patients is immunogenetically distinct from typical AIH.Citation63 HLA-DR4 is a resistant, whereas DR9 is a susceptible, HLA phenotype of histologically atypical AIH. These findings strongly suggest that histologically atypical AIH is not a transient histological feature of very early typical AIH but a feature of a distinctive subtype of AIH.

On the whole, the prognosis of histologically atypical AIH is good and the response to immunosuppression is excellent. However, this type of AIH may rapidly develop into ALF, which can be a cause of death.Citation64 Thus, quick and accurate diagnosis is required. However, the AIH score of this type of AIH is lower than that of classical AIH, chiefly because of the lower prevalence of ANA and lower levels of IgG. As this type of AIH responds well to corticosteroid therapy if there is no delay in treatment, appropriate examinations to determine a definite diagnosis should be performed as soon as possible and sufficient immunosuppression therapy should be started without delay.

The most important differential diagnosis of histologically atypical AIH is DILI, in which zone 3 hepatocytes are mainly affected. There are many drugs and chemicals that induce zone 3 necrosis. The histological findings of DILI are sometimes quite similar to those of AIH accompanying CZN. Therefore, liver biopsy is not sufficient to distinguish histologically atypical AIH from DILI.

CZN is a relatively rare condition that accounts for 10–20% of AIH cases.Citation63 In the future, CZN must be clarified using unified criteria, and the clinicopathological features of this subtype of AIH should be confirmed by a large-scale study.

Treatment

The aim of treatment for AIH is to achieve complete remission of disease, followed by maintenance of remission and prevention of disease progression. Asymptomatic AIH is claimed not to require immunosuppressive therapy. No difference is observed in the prognosis of mild to moderate cases, irrespective of whether these cases are treated with immunosuppressive drugs.Citation65 In contrast, the 10-year survival rate for mild, untreated cases is reported to be significantly lower than for treated cases.Citation66 In mild to moderate cases, the condition can spontaneously resolve, but this happens infrequently and there is a risk that the disease will flare up during the clinical course. There are also some patients whose liver disease progresses asymptomatically, and the diagnosis is not established till severe fibrosis or cirrhosis has developed. Therefore, if medical intervention is deferred, the patient must be carefully monitored. When these cases are treated, potential adverse reactions caused by the therapeutic agent must be monitored.

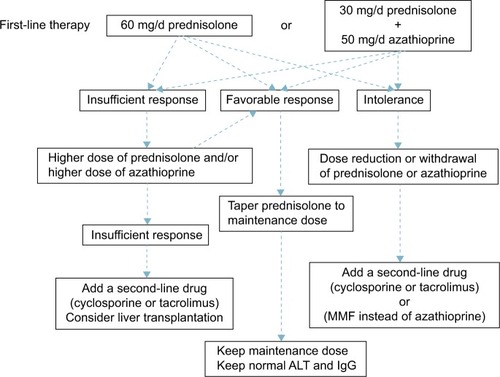

The guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) state that treatment is necessary for advanced fibrosis, or in cases that are histologically active (hepatic activity index [HAI] score of 4/18 or higher).Citation67 When the ALT level is less than three times the ULN, the HAI score is <4/18, and there is no advanced fibrosis, treatment should be based on the patient’s age and pathology; if no treatment is selected, ALT and IgG levels should be measured every 3 months. If these levels are elevated, a follow-up liver biopsy is recommended; if the disease has become active, treatment should be initiated. The current strategy for the treatment of adult AIH is summarized in .

Figure 2 Current treatment strategy for adult autoimmune hepatitis.

Prednisolone (PSL) monotherapy or PSL and azathioprine combination therapy is used for first-line AIH treatment. These two treatments have equivalent therapeutic effect.Citation68 In combination treatment, the dose of PSL is lower than in PSL monotherapy, reducing the PSL-induced adverse reactions. Azathioprine combination therapy is preferred for postmenopausal women and for patients with osteoporosis, unstable diabetes, obesity, or hypertension. The recommended initial PSL dose is 60 mg (or 1 mg/kg of body weight) in monotherapy and 30–40 mg in combination with azathioprine. The azathioprine dose is generally 50 mg. Azathioprine is contraindicated in patients with severe cytopenia, thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) deficiency, pregnancy, or cancer.Citation69 The TPMT genetic polymorphism is associated with reduced TPMT activity, so it is preferable to identify the genotype prior to the use of azathioprine to avoid myelosuppression.Citation70

With PSL monotherapy, the dose should be decreased by 10 mg every week; the rate of dose reduction is eased from 30 mg downward to 5 mg every 1–2 weeks. Rapid reduction in the PSL dosage is an independent risk factor for recurrence.Citation71 As the prognosis worsens in patients who have had two or more relapses, maintaining remission is very important.Citation72 The PSL maintenance dose is ≤10 mg/d. Treatment should be continued until the transaminases, total bilirubin, gammaglobulin, IgG, and liver tissue have normalized. Therefore, it is essential to continue maintenance treatment over a long period.

Cases in which ALT level does not decrease to less than two times the ULN, relapsed cases, and cases that do not respond to high-dose PSL are considered PSL-resistant. In the case of PSL resistance, once drug compliance has been confirmed, increasing the PSL dose or adding or increasing the azathioprine dose should be considered. In patients who do not tolerate PSL or azathioprine, dose reduction, or withdrawal of the drug should be considered. As an alternative therapy, administration of cyclosporine,Citation73 tacrolimus,Citation74 or mycophenolate mofetilCitation13 has been shown to be effective. There are a few reports on the efficacy of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, rituximab, and infliximab, but no consensus has been reached on the usage of these drugs.

Budesonide may be considered for combination therapy with azathioprine instead of PSL, but there is little likelihood of efficacy in cases resistant to PSL therapy.Citation75 Budesonide is metabolized by the liver and has a 90% first-pass effect; it has few systemic effects and is characterized by a lack of adverse drug reactions.Citation76 However, as it is metabolized by the liver, it is contraindicated in patients with cirrhosis or patients with a liver shunt. In a prospective study of the additive effect of UDCA for PSL-treated patients, UDCA did not facilitate PSL dose reduction or reduce histological activity.Citation77 In Japan, UDCA is administered to patients who have mild AIH with low disease activity and preserved liver function, and it has been found to have a positive effect in decreasing transaminase levels.Citation78 However, the long-term effect of UDCA is unknown.

Mycophenolate mofetil (2 g daily orally) is administered to patients as an alternative to azathioprine when the patient has not responded to standard treatment. As mycophenolate mofetil and PSL combination therapy has a higher rate of inducing complete remission than azathioprine and PSL, and remission is maintained after PSL is discontinued, mycophenolate mofetil may come to replace azathioprine as the standard treatment.Citation79 However, this treatment is problematic in terms of the large number of adverse drug reactions, including rash, alopecia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.Citation80

Elderly AIH patients respond well to PSL therapy, with less likelihood of treatment resistance, so PSL should be used. It is essential to be aware of the adverse effects of PSL in older patients. More than the prescribed dose should not be taken. With severe AIH, there is no difference in sepsis rate between PSL treatment and nontreatment groups. Even if PSL therapy fails, PSL does not adversely affect the prognosis.Citation81 Therefore, adequate doses of steroids should be administered urgently in these patients.

The 5-year survival rate for AIH living-liver transplantation is good, at ~80%, with no evidence of recurrence in transplanted livers in Japan,Citation82 although a significant recurrence rate has been reported in Europe and the US.Citation83 The recurrence rate after transplantation may differ in different races; this question requires further investigation. Splenectomy may inhibit the recurrence of AIH after liver transplantation.Citation84 In a mouse AIH model, by removing central Treg cells, splenectomy prolonged the effects of a corticosteroid.Citation85 Therefore, splenectomy may be an additional option for the treatment of AIH.

As regards future therapies, correction of disturbed immunity in AIH, in particular the restoration of failed Treg cellsCitation30 has shown promise. In a type 2 AIH mouse model, remission was introduced by transferring ex vivo expanded autologous CXCR3-positive Tregs.Citation86 Therefore, retrieval of peripheral tolerance by adoptive transfer of Tregs could be a promising therapy for refractory AIH.

Conclusion

The clinical spectrum of AIH is widely distributed and the diagnosis of atypical AIH is not necessarily easy. AIH may overlap with PBC or PSC, a condition that is known as PBC/PSC-AIH overlap syndrome. However, whether overlap syndrome is a distinctive disease entity or merely a variant of PBC/PSC is an issue to be solved in the future. Similarly, whether DIAIH is a distinctive disease entity or merely a subtype of DILI that exhibits autoimmune phenomena is controversial. An increase in the incidence of NAFLD/NASH may lead to an increase in the cases of AIH with coincident NAFLD/NASH. Coincidence of NAFLD/NASH may be problematic, because the outcome may be aggravated and the efficacy of corticosteroids may be attenuated. Histologically, the significance of CZN should be examined extensively. In the treatment of AIH, development of novel drugs based on the immunological mechanisms of AIH is awaited.

After viral hepatitis is eliminated, AIH will become one of the central themes of hepatology. In the future, AIH will attract more and more attention because many serious issues related to its management remain to be resolved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CowlingDCMackayIRTaftLILupoid hepatitisLancet195627169571323132613386250

- GregorioGVPortmannBReidFAutoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experienceHepatology19972535415479049195

- NewtonJLBurtADParkJBMathewJBassendineMFJamesOFAutoimmune hepatitis in older patientsAge Ageing19972664414449466294

- OmagariKKinoshitaHKatoYClinical features of 89 patients with autoimmune hepatitis in Nagasaki Prefecture, JapanJ Gastroenterol199934222122610213122

- GregorioGVMcFarlaneBBrackenPVerganiDMieli-VerganiGOrgan and non-organ specific autoantibody titres and IgG levels as markers of disease activity: a longitudinal study in childhood autoimmune liver diseaseAutoimmunity200235851551912765477

- MuratoriPLalanneCFabbriACassaniFLenziMMuratoriLType 1 and type 2 autoimmune hepatitis in adults share the same clinical phenotypeAliment Pharmacol Ther201541121281128725898847

- UmemuraTOtaMGenetic factors affect the etiology, clinical characteristics and outcome of autoimmune hepatitisClin J Gastroenterol20158636036626661115

- HeneghanMAYeomanADVermaSSmithADLonghiMSAutoimmune hepatitisLancet201338299021433144423768844

- AlvarezFBergPABianchiFBInternational Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitisJ Hepatol19993192993810580593

- ChazouillèresOWendumDSerfatyLMontembaultSRosmorducOPouponRPrimary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapyHepatology19982822963019695990

- TiniakosDGBrainJGBuryYARole of histopathology in autoimmune hepatitisDig Dis201533suppl 2536426642062

- HeneghanMAMcFarlaneIGCurrent and novel immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune hepatitisHepatology200235171311786954

- ZachouKGatselisNKArvanitiPA real-world study focused on the long-term efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil as first-line treatment of autoimmune hepatitisAliment Pharmacol Ther201643101035104726991238

- DonaldsonPTImmunogenetics in liver diseaseBaillieres Clin Gastroenterol19961035335498905122

- SekiTKiyosawaKInokoHOtaMAssociation of autoimmune hepatitis with HLA-Bw54 and DR4 in Japanese patientsHepatology1990126130013042175292

- Eskandari-NasabETahmasebiAHashemiMMeta-analysis: the relationship between CTLA-4 +49 A/G polymorphism and primary biliary cirrhosis and type I autoimmune hepatitisImmunol Invest201544433134825942345

- WebbGJHirschfieldGMUsing GWAS to identify genetic predisposition in hepatic autoimmunityJ Autoimmun201666253926347073

- BittencourtPLGoldbergACCançadoELGenetic heterogeneity in susceptibility to autoimmune hepatitis types 1 and 2Am J Gastroenterol19999471906191310406258

- JungeNTiedauMVerboomMHuman leucocyte antigens and pediatric autoimmune liver disease: diagnosis and prognosisEur J Pediatr2016175452753726567543

- HassanNSiddiquiARAbbasZClinical profile and HLA typing of autoimmune hepatitis from PakistanHepat Mon20131312e1359824358040

- UmemuraTKatsuyamaYYoshizawaKHuman leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes affect clinical characteristics and progression of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in JapanPLoS One201496e10056524956105

- FurumotoYAsanoTSugitaTEvaluation of the role of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese type 1 autoimmune hepatitisBMC Gastroenterol20151514426489422

- van GervenNMde BoerYSZwiersADutch Autoimmune Hepatitis Study GroupHLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DRB1*04:01 modify the presentation and outcome in autoimmune hepatitis type-1Genes Immun201516424725225611558

- Djilali-SaiahIFakhfakhALouafiHCaillat-ZucmanSDebrayDAlvarezFHLA class II influences humoral autoimmunity in patients with type 2 autoimmune hepatitisJ Hepatol200645684485017050030

- YangFWangQBianZRenLLJiaJMaXAutoimmune hepatitis: east meets westJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20153081230123625765710

- BuxbaumJQianPAllenPMPetersMGHepatitis resulting from liver-specific expression and recognition of self-antigenJ Autoimmun200831320821518513923

- LonghiMSMaYMieli-VerganiGVerganiDAetiopathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitisJ Autoimmun201034171419766456

- ZierdenMKühnenEOdenthalMDienesHPEffects and regulation of autoreactive CD8+ T cells in a transgenic mouse model of autoimmune hepatitisGastroenterology2010139397598620639127

- PeiselerMSebodeMFrankeBFOXP3+ regulatory T cells in autoimmune hepatitis are fully functional and not reduced in frequencyJ Hepatol201257112513222425700

- GrantCRLiberalRHolderBSDysfunctional CD39(POS) regulatory T cells and aberrant control of T-helper type 17 cells in autoimmune hepatitisHepatology20145931007101523787765

- WadaYSatoCTomitaKPossible autoimmune hepatitis induced after chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infectionClin J Gastroenterol201471586126183510

- ChibaTGotoSYokosukaOFatal chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection mimicking autoimmune hepatitisEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200416222522815075999

- YamashitaHShimizuATsuchiyaHChronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection mimicking autoimmune hepatitis exacerbation in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosusLupus201423883383624608961

- BonderARetanaAWinstonDMLeungJKaplanMMPrevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20119760961221440668

- DienesHPErberichHDriesVSchirmacherPLohseAAutoimmune hepatitis and overlap syndromesClin Liver Dis20026234936212122860

- ChouMJLeeSLChenTYTsayGJSpecificity of antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosisAnn Rheum Dis19955421481517702406

- KobayashiMKakudaYHaradaKClinicopathological study of primary biliary cirrhosis with interface hepatitis compared to autoimmune hepatitisWorld J Gastroenterol201420133597360824707143

- KuiperEMZondervanPEvan BuurenHRParis criteria are effective in diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20108653053420304098

- ZhangHLiSYangJA meta-analysis of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy versus combination therapy with corticosteroids for PBC-AIH-overlap syndrome: evidence from 97 monotherapy and 117 combinationsPrz Gastroenterol201510314815526516380

- OzaslanEEfeCHeurgué-BerlotAFactors associated with response to therapy and outcome of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis with features of autoimmune hepatitisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201412586386924076417

- van BuurenHRvan HoogstratenHJETerkivatanTSchalmSWVleggaarFPHigh prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitisJ Hepatol200033454354811059858

- TencaAFärkkiläMArolaJJaakkolaTPenaginiRKolhoKLClinical course and prognosis of pediatric-onset primary sclerosing cholangitisUnited European Gastroenterol J201644562569

- VerdonkRCLozanoMFvan den BergAPGouwASBile ductal injury and ductular reaction are frequent phenomena with different significance in autoimmune hepatitisLiver Int20163691362136926849025

- BjörnssonETalwalkarJTreeprasertsukSDrug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: clinical characteristics and prognosisHepatology20105162040204820512992

- AllaVAbrahamJSiddiquiJAutoimmune hepatitis triggered by statinsJ Clin Gastroenterol200640875776116940892

- SuzukiABruntEMKleinerDEThe use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injuryHepatology201154393193921674554

- LicataAMaidaMCabibiDClinical features and outcomes of patients with drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis: a retrospective cohort studyDig Liver Dis201446121116112025224696

- YeongTTLimKHGoubetSParnellNVermaSNatural history and outcomes in drug-induced autoimmune hepatitisHepatol Res2016463E79E8825943838

- de BoerYSKosinskiASUrbanTJDrug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with drug-induced liver injuryClin Gastroenterol Hepatol Epub2016614

- BeaunePHLecoeurSImmunotoxicology of the liver: adverse reactions to drugsJ Hepatol199726suppl 23742

- De Luca-JohnsonJWangensteenKJHansonJKrawittEWilcoxRNatural history of patients presenting with autoimmune hepatitis and coincident nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseDig Dis Sci20166192710272027262844

- MüllerPMessmerMBayerMPfeilschifterJMHintermannEChristenUNon-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) potentiates autoimmune hepatitis in the CYP2D6 mouse modelJ Autoimmun201669515826924542

- LoriaPLonardoALeonardiFNon-organ-specific autoantibodies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: prevalence and correlatesDig Dis Sci200348112173218114705824

- HuKQYangHLinYCLindsayKLRedekerAGClinical profiles of chronic hepatitis C in a major county medical center outpatient setting in United StatesInt J Med Sci2004129210015912201

- MaYPeakmanMLobo-YeoADifferences in immune recognition of cytochrome P4502D6 by liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody in autoimmune hepatitis and chronic hepatitis C virus infectionClin Exp Immunol199497194998033426

- KammerARvan der BurgSHGrabscheidBMolecular mimicry of human cytochrome P450 by hepatitis C virus at the level of cytotoxic T cell recognitionJ Exp Med1999190216917610432280

- EfeCWahlinSOzaslanEDiagnostic difficulties, therapeutic strategies, and performance of scoring systems in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and concurrent hepatitis B/CScand J Gastroenterol201348450450823448312

- PrattDSFawazKARabsonADellelisRKaplanMMA novel histological lesion in glucocorticoid-responsive chronic hepatitisGastroenterology19971136646689247489

- MiyakeYIwasakiYTeradaRClinical features of Japanese type 1 autoimmune hepatitis patients with zone III necrosisHepatol Res2007371080180517559422

- ZenYNotsumataKTanakaNNakanumaYHepatic centrilobular zonal necrosis with positive antinuclear antibody: a unique subtype or early disease of autoimmune hepatitis?Hum Pathol200738111669167517669466

- HoferHOesterreicherCWrbaFFerenciPPennerECentrilobular necrosis in autoimmune hepatitis: a histological feature associated with acute clinical presentationJ Clin Pathol200659324624916505273

- SinghRNairSFarrGMasonAPerrilloRAcute autoimmune hepatitis presenting with centrizonal liver disease: case report and review of the literatureAm J Gastroenterol200297102670267312385459

- AizawaYAbeHSugitaTCentrilobular zonal necrosis as a hallmark of a distinctive subtype of autoimmune hepatitisEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201628439139726657454

- StravitzRTLefkowitchJHFontanaRJAcute Liver Failure Study GroupAutoimmune acute liver failure: proposed clinical and histological criteriaHepatology201153251752621274872

- FeldJJDinhHArenovichTMarcusVAWanlessIRHeathcoteEJAutoimmune hepatitis: effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcomeHepatology2005421536215954109

- CzajaAJFeatures and consequences of untreated type 1 autoimmune hepatitisLiver Int200929681682319018980

- European Association for the Study of the LiverEASL clinical practice guidelines: autoimmune hepatitisJ Hepatol2015634971100426341719

- LamersMMvan OijenMGPronkMDrenthJPTreatment options for autoimmune hepatitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trialsJ Hepatol201053119119820400196

- MannsMPCzajaAJGorhamJDAmerican Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesDiagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitisHepatology20105162193221320513004

- KrynetskiEYTaiHLYatesCRGenetic polymorphism of thiopurine S-methyltransferase: clinical importance and molecular mechanismsPharmacogenetics1996642792908873214

- TakahashiAOhiraHAbeKIntractable Liver and Biliary Diseases Study Group of Japan. Rapid corticosteroid tapering: important risk factor for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis relapse in JapanHepatol Res201545663864425070037

- YoshizawaKMatsumotoAIchijoTLong-term outcome of Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitisHepatology201256266867622334246

- ShermanKENarkewiczMPintoPCCyclosporine in the management of corticosteroid-resistant type I autoimmune chronic active hepatitisJ Hepatol1994216104010477699225

- AqelBAMachicaoVRosserBSatyanarayanaRHarnoisDMDicksonRCEfficacy of tacrolimus in the treatment of steroid refractory autoimmune hepatitisJ Clin Gastroenterol200438980580915365410

- CzajaAJLindorKDFailure of budesonide in a pilot study of treatment-dependent autoimmune hepatitisGastroenterology200011951312131611054389

- DanielssonAPrytzHOral budesonide for treatment of autoimmune chronic active hepatitisAliment Pharmacol Ther1994865855907696446

- CzajaAJCarpenterHALindorKDUrsodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled treatment trialHepatology19993061381138610573515

- MiyakeYIwasakiYKobashiHEfficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid for Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitisHepatol Int20093455656219847577

- ZachouKGatselisNPapadamouGRigopoulouEIDalekosGNMycophenolate for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: prospective assessment of its efficacy and safety for induction and maintenance of remission in a large cohort of treatment-naïve patientsJ Hepatol201155363664621238519

- HlivkoJTShiffmanMLStravitzRTA single center review of the use of mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of autoimmune hepatitisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2008691036104018586559

- YeomanADWestbrookRHZenYPrognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): the role of corticosteroids in modifying outcomeJ Hepatol201461487688224842305

- YamashikiNSugawaraYTamuraSLiving-donor liver transplantation for autoimmune hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndromeHepatol Res201242101016102322548727

- DemetrisAJAdeyiOBellamyCOBanff Working Group Liver biopsy interpretation for causes of late liver allograft dysfunctionHepatology200644248950116871565

- XuYTLiuDJMengFYLiGBLiuJPossible benefit of splenectomy in liver transplantation for autoimmune hepatitisHepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int201413332833124919618

- MaruokaRAokiNKidoMSplenectomy prolongs the effects of corticosteroids in mouse models of autoimmune hepatitisGastroenterology20131451209.e220.e23523671

- LapierrePBélandKYangRAlvarezFAdoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded regulatory T cells in an autoimmune hepatitis murine model restores peripheral toleranceHepatology201357121722722911361