Abstract

Background:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder long considered a diagnosis of exclusion, has chronic symptoms that vary over time and overlap with those of non-IBS disorders. Traditional symptom-based criteria effectively identify IBS patients but are not easily applied in clinical practice, leaving >40% of patients to experience symptoms up to 5 years before diagnosis.

Objective:

To review the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected IBS, strengths and weaknesses of current methodologies, and newer diagnostic tools that can augment current symptom-based criteria.

Methods:

The peer-reviewed literature (PubMed) was searched for primary reports and reviews using the limiters of date (1999–2009) and English language and the search terms irritable bowel syndrome, diagnosis, gastrointestinal disease, symptom-based criteria, outcome, serology, and fecal markers. Abstracts from Digestive Disease Week 2008–2009 and reference lists of identified articles were reviewed.

Results:

A disconnect is apparent between practice guidelines and clinical practice. The American Gastroenterological Association and American College of Gastroenterology recommend diagnosing IBS in patients without alarm features of organic disease using symptom-based criteria (eg, Rome). However, physicians report confidence in a symptom-based diagnosis without further testing only up to 42% of the time; many order laboratory tests and perform sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies despite good evidence showing no utility for this work-up in uncomplicated cases. In the absence of diagnostic criteria easily usable in a busy practice, newer diagnostic methods, such as stool-form examination, fecal inflammatory markers, and serum biomarkers, have been proposed as adjunctive tools to aid in an IBS diagnosis by increasing physicians’ confidence and changing the diagnostic paradigm to one of inclusion rather than exclusion.

Conclusion:

New adjunctive testing for IBS can augment traditional symptom-based criteria, improving the speed and safety with which a patient is diagnosed and avoiding unnecessary, sometimes invasive, testing that adds little to the diagnostic process in suspected IBS.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits.Citation1,Citation2 As such, IBS occurs in the absence of identifiable physical, radiologic, or laboratory indications of organic disease.Citation2,Citation3 Characterized as a “brain–gut disorder,”Citation4 IBS is associated with such altered physiologic processes as changes in gut motility,Citation5,Citation6 visceral hypersensitivity,Citation7 and altered immune activation of the gut mucosa and intestinal microflora.Citation6,Citation8

A recent systematic review of IBS epidemiologic studies noted an IBS prevalence of 3%–20% in North America, with as many as 45 million adults experiencing symptoms annually.Citation9 In North America, IBS is more common among women than men,Citation2,Citation9,Citation10 is diagnosed more often before age 50,Citation2,Citation9,Citation10 and appears to be more common in lower socioeconomic populations.Citation11,Citation12

IBS accounts for significant health care resource utilization and economic burden. Although most symptomatic individuals do not seek medical care,Citation13 an estimated 3.6 million annual physician visits in the United States and US $20 billion in annual direct and indirect costs are attributed to IBS symptomatology.Citation14 Direct costs are often high in the initial diagnostic phase as historically IBS has been considered a diagnosis of exclusion, prompting sequential testing and invasive procedures in an attempt to identify organic GI disease.Citation2,Citation3,Citation15 Dean et alCitation16 found that IBS-related symptoms reduced work productivity by an estimated 21% per week (presenteeism), thus increasing costs to employers. Because IBS is not a mortal illness, the impact on patients is often underestimated. In reality, however, IBS patients have substantially poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than the general population and HRQoL that is on par with that seen in diabetes, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.Citation17,Citation18 Furthermore, IBS patients have been noted to have worse body pain, lower energy or increased fatigue, and poorer social functioning than patients with dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease.Citation18 Earlier definitive diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment have the capacity to reduce some of these consequences of IBS symptoms.Citation16

This article reviews the practical diagnostic evaluation of patients presenting with symptoms that may be related to IBS, the strengths and weaknesses of current diagnostic methodologies, and the newer diagnostic tools that can augment current symptom-based criteria.

Diagnosis of IBS in clinical practice

Clinical presentation

The hallmark clinical feature of IBS is abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits.Citation1 Patients with symptoms consistent with constipation-predominant IBS may describe bloating, feelings that their bowel is being incompletely evacuated, and straining, whereas those with the diarrhea-predominant form typically report abdominal pain, gas, urgency, and loose stools, with more than 30% experiencing loss of bowel control.Citation10,Citation19,Citation20 The typical patient is a young woman with abdominal discomfort that is relieved by passage of multiple loose liquid stools. Her symptoms will have been present for more than 3 months and may be exacerbated by factors such as fatty foods or stress. Typically, no alarm features of organic disease, such as unintentional weight loss or rectal bleeding, are present. The clinical course of IBS is chronic although symptoms are extremely variable and fluctuate over time.Citation21 Nearly half of IBS patients report experiencing daily episodes, whereas about 75% experience at least two episodes per week.Citation19

Challenges in IBS diagnosis

The symptoms of IBS are heterogeneous, wax and wane over time,Citation1,Citation13,Citation22 and frequently overlap and/or coexist with symptoms of other common GI and non-GI disorders.Citation22 Unfortunately, no one symptom or test is pathognomonic for IBS. Symptoms of IBS may overlap with symptoms found in other disorders, such as chronic constipation, functional dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and lactose intolerance.Citation22,Citation23 IBS can coexist with other functional disorders, most notably fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, temporomandibular joint disorder, and chronic pelvic pain,Citation24,Citation25 and psychological conditions, such as anxiety, symptom-related fears, and somatization.Citation4,Citation13,Citation24

The differential diagnosis of IBS can be broadCitation3 and may include IBD, colorectal cancer, enteric infections, systemic hormonal disturbances, and diseases associated with malabsorption.Citation2 Alarm features that have traditionally increased suspicion for organic disease include rectal bleeding, weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, nocturnal symptoms, and a family history of such organic diseases as colorectal cancer, IBD, and celiac disease.Citation2,Citation13 However, with the exception of anemia and weight loss, which have good specificity for organic disease, most alarm features have poor overall accuracy for organic pathology, including colorectal cancer.Citation2,Citation26

Medicolegal concerns about missing organic pathology have contributed to the practice of treating IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion,Citation2,Citation3,Citation27 a common approach by many practitionersCitation28 that leads to unnecessary testing in patients with symptoms consistent with IBS and no alarm features. SpiegelCitation28 demonstrated that physicians who view IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion order 1.6 more diagnostic tests and spend US $364 more per patient than those who do not. However, evidence indicates that sequential testing is unlikely to uncover the underlying GI organic disease in patients without “alarm features,”Citation2,Citation29,Citation30 and both the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommend using accepted symptom-based diagnostic criteria to make a positive diagnosis of IBS rather than an exhaustive diagnostic investigation.Citation2,Citation13,Citation31

Despite testing, or even because of it, the diagnosis of IBS is often missed or delayed. In a survey,Citation27 fewer than half of 35 health maintenance organization-based family practitioners could identify typical IBS symptomsCitation27 and only 35% knew that the Manning, Rome I, and Rome II criteria are used to diagnose IBS. Other physicians report feeling comfortable diagnosing IBS at the patient’s first visit only 40% of the time.Citation32 As a consequence of this lack of diagnostic confidence, more than 40% of patients experience IBS symptoms for at least 5 years before diagnosis is made.Citation10,Citation19 In addition, these patients endure unnecessary tests, procedures, or therapies and the associated financial burden that accompanies them.Citation33 Delayed diagnosis can also increase anxiety in patients,Citation34 more than half of whom think IBS is a “catch-all” diagnosisCitation35 and expect numerous tests to be performed to find the “real” diagnosis.Citation34 Common misconceptions about the diagnosis and the natural history of IBS negatively affect patients’ emotional well-being and HRQoL.Citation35,Citation36

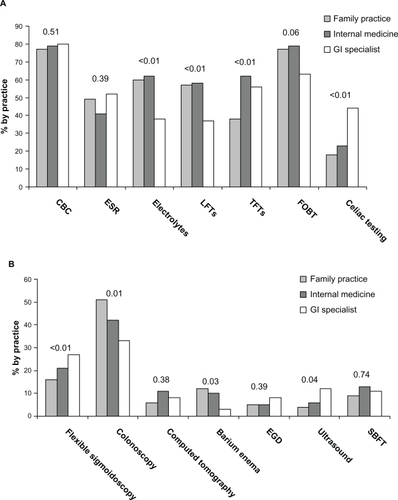

Lacy et alCitation32 analyzed survey responses from 472 gastroenterologists, internists, and family physicians to ascertain their understanding of IBS and practice patterns. Although the physicians reported feeling capable of diagnosing IBS at the initial visit without further testing in patients without alarm features up to 42% of the time, the majority of gastroenterologists report commonly ordering laboratory tests and nearly one-third will perform flexible sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies ().Citation32 All three types of physicians reported a primary goal of excluding organic disease, with symptom relief being only of secondary importance. Overall, IBS symptoms account for nearly 25% of colonoscopies in patients younger than 50 years.Citation2,Citation37,Citation38

Figure 1 Laboratory and diagnostic tests commonly ordered, presented by physician type.Citation32 More than 1 response could be chosen. A, Laboratory tests by practice type. “Other” laboratory tests (≤2%) are not represented. B, Diagnostic tests by practice type. “Other” diagnostic tests (4%–11%) and “no studies ordered” (34%–38%) are not represented. P values are shown.

Current state of IBS diagnostics

Symptom-based criteria

Several sets of criteria have been developed to identify and standardize the diagnosis of IBS ().Citation2,Citation3 The early Manning criteriaCitation39 identified six symptoms that increase the likelihood of an IBS diagnosis but do not stipulate a required number or duration of symptoms. In 1984, Kruis et alCitation40 developed a system of symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory results, and in 1990, an international working groupCitation41 developed Rome I criteria in an attempt to reduce unnecessary testing and provide a uniform framework for selecting patients for diagnostic and therapeutic trials in IBS.Citation3,Citation31 These criteria were revised in 1999 by the Rome II working group and again in 2006 by the Rome III working group ().Citation1,Citation42 Unfortunately, such criteria can be difficult to apply in busy practices, and despite extensive use in research settings, the Rome II and III criteria are not sufficiently validated.Citation2,Citation3,Citation31 Indeed, only one study evaluated the accuracy of the Rome I criteria for diagnosing IBS.Citation43

Table 1 Comparison of symptom-based criteria

The utility of symptom-based criteria in primary care settings has been brought into question.Citation31,Citation44 As such, alternative IBS diagnostic criteria have been sought. In one such instance, 10 European family practitioners developed a structured consensus process to define IBS diagnostic criteria. In their process, the key features identified for IBS diagnostic purposes differed substantially from those stipulated by Rome III.Citation44

Traditional diagnostic tests for IBS

The traditional diagnostic work-up of IBS includes common tests that may be helpful in differentiating IBS with alarm features of organic disease although they are not recommended in patients with typical IBS symptoms who do not have alarm features.Citation2,Citation13,Citation43 The choice of test is usually guided by the nature and severity of symptoms and the patient’s expectations and concerns.Citation2 Advantages and disadvantages of these traditional tests are summarized in .

Table 2 Comparison of traditional diagnostic methods

Newer diagnostic tools, such as the examination of stool forms, fecal inflammatory markers, and the use of serum biomarker, may be useful adjuncts to traditional evaluations of patients with suspected IBS. These simple tests may allow clinicians to distinguish IBS from non-IBS disorders in a cost-effective manner,Citation45,Citation46 possibly facilitating a paradigm shift from approaching IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion to one of inclusion.Citation45 Pimentel et alCitation45 have advocated use of specific clinical questions regarding bowel form and function that may help distinguish between IBS and non-IBS diarrheal disease with a high sensitivity. Already used routinely in some European countries,Citation47 fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are highly sensitive and specific for intestinal inflammation and can differentiate IBD from IBS.Citation23,Citation48 Recently, an IBS diagnostic panel composed of 10 serum biomarkers that are linked to multiple regulatory pathways and proteins associated with IBS has been developed. Using a smart diagnostic algorithm to interpret the data obtained, this panel may be especially helpful in the early stages of the diagnostic process in confirming suspected IBS.Citation33

Routine blood and stool hemoccult tests

The AGA recommends a screening of complete blood count and stool hemoccult for patients presenting with IBS symptoms of short duration, family history of colorectal cancer or IBD, older age at symptom onset, or lack of concurrent psychosocial difficulties.Citation13 However, these tests offer little value in identifying organic disease in patients with typical IBS symptoms but no alarm features. In a study of 196 patients with suspected IBS, serum chemistries and complete blood counts failed to uncover the underlying organic disease in any patient.Citation49 Similarly, a review of data from five studies in 2,160 IBS patients showed comparable prevalence rates of abnormal thyroid function test results between the study patients (4.2%) and the general population (5%–9%).Citation2 Further, a causal relationship between the thyroid dysfunction and IBS symptoms was not established.Citation2

Stool examinations for ova and parasites

Stool examinations may be useful if the patients’ symptom pattern, geographic area, and clinical features (eg, diarrhea in an area of known endemic infection) suggest an infectious etiology.Citation13 However, such tests are not recommended for routine use in patients without alarm features or infection,Citation2,Citation13 as findings are significant in fewer than 2% of patients with IBS.Citation2,Citation49,Citation50

Carbohydrate breath test

The carbohydrate breath test has been used by gastroenterologists for many years to detect lactose malabsorption. The test measures exhaled levels of hydrogen and/or methane produced during the metabolism of carbohydrate substrates by intestinal bacteria.Citation51 Breath testing for lactose intolerance may be useful in patients with typical IBS symptoms and suspected lactose maldigestion. It is important, however, to establish that dietary intake of lactose is >240 mL of milk (or equivalent) per day before testing for lactose intolerance, as Suarez et alCitation52 have shown that patients with documented lactose malabsorption are able to tolerate 240 mL of milk per day with minimal or no symptoms. A systematic review of data from seven studies involving 2,149 IBS patients demonstrated a 35% prevalence of lactose maldigestion (95% confidence interval [CI]: 17–56) by lactose breath testing,Citation2 whereas a separate analysis of three case-control studies involving 425 patients (251 of whom had IBS) revealed a prevalence of 38% in IBS patients vs 26% in controls (odds ratio [OR] = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.27–5.22).Citation2 Despite the frequent occurrence of lactose intolerance in patients with IBS, no causal relationship has been established between lactose intolerance and IBS symptoms. However, given the possibility that IBS patients are more sensitive to the clinical consequences of lactose maldigestion,Citation53 the ACG IBS Task Force has recommended considering a lactose hydrogen breath test in patients whose history and food diary review suggest potential lactose maldigestion.Citation2

Recently, carbohydrate breath test has been used in an attempt to identify patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).Citation51 Emerging evidence suggests that SIBO plays a pathogenic role in IBS,Citation54,Citation55 although this remains contentious. The use of carbohydrate breath test to diagnose SIBO in IBS patients has yielded conflicting results. In a systematic review by the ACG IBS Task Force, the prevalence of a positive lactulose breath test was 65% (95% CI: 47–81) in 432 IBS patients from three studies, whereas the prevalence of a positive glucose breath test was 36% (95% CI: 29–43) in 208 patients from two studies.Citation2 Because lactulose is not absorbed by the intestine, lactulose breath tests should detect bacteria anywhere along the gut.Citation51,Citation56 Because glucose is absorbed rapidly, glucose breath testing can detect bacteria only in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, demonstrating lower sensitivity than lactulose breath testing.Citation51,Citation56 Posserud et alCitation57 used jejunal aspirate culture to assess the prevalence of SIBO in 162 patients with IBS and found a prevalence of SIBO (defined as ≥105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) of 4% in patients with IBS (7 of 162) and in controls (1 of 26). Glucose hydrogen breath testing performed on 54 IBS patients and 20 controls with <105 CFU/mL was positive in only one IBS patient; lactulose hydrogen breath testing in 46 IBS patients and 21 controls with <105 CFU/mL yielded positive results in 15% (7 of 46) of IBS patients and 20% (4 of 21) of controls.Citation57 The ACG IBS Task Force does not recommend breath testing for SIBO in patients with IBS.Citation2

Celiac testing

The prevalence of serologic evidence of celiac disease among IBS patients (endomysial antibodies [EMA] or tissue transglutaminase antibodies [anti-tTG]) is more than three fold higher than among controls without IBS, and the prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease is four fold higher than among controls.Citation58 Routine serologic screening for celiac disease is recommended for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) or mixed features of IBS (IBS-M).Citation2 EMA and anti-tTG have a higher positive predictive value for celiac disease than the immunoglobulin (Ig) A-class antigliadin antibodies.Citation58

Imaging

Neither abdominal nor colonic imaging tests are likely to reveal the structural abnormalities that explain symptoms of IBS in patients with no alarm features.Citation2,Citation29 In a study of 125 patients with suspected IBS on the basis of the Rome I criteria, abdominal ultrasound failed to reveal any serious intra-abdominal pathology.Citation29 Although abnormalities were detected in 18% of patients, findings did not change a diagnosis.Citation29 In three studies, in a total of 636 IBS patients, imaging with barium enema or colonoscopy revealed organic or structural disease in 1.3% of patients, which does not exceed the prevalence in the general population.Citation2

Endoscopy or colonoscopy

Studies evaluating endoscopic investigation for suspected IBS do not support their routine use in patients without alarm features. Hamm et alCitation50 assessed the value of such tests as flexible sigmoidoscopies, barium enemas, and colonoscopies in 1,452 patients meeting Rome criteria for at least 6 months. Among the 306 patients undergoing colonic examination, abnormalities were detected in seven patients (2%): IBD in three, colonic obstruction in one, and colonic polyps without malignancy in three.Citation50 In a smaller study of 196 patients with IBS, 43 colonic structural abnormalities were found in 34 patients. Nine (26%) of these patients had indicators suggestive of organic diseaseCitation49 and, of these, only two (1%) had abnormalities (one colitis, one colon cancer) that may have caused IBS symptoms.Citation3,Citation49 MacIntosh et alCitation59 performed flexible sigmoidoscopy with rectal biopsy in 89 patients with IBS, most of whom met Rome I criteria. None of the findings suggested alternative diagnoses that could account for the GI symptoms in any patient. Investigators concluded that such studies are costly and unnecessary in IBS.Citation3,Citation59 A retrospective reviewCitation37 of data from 458 patients found that colonoscopy had a low diagnostic yield and normal findings were not associated with higher HRQoL owing to diagnostic reassurance.

Based on these and other findings, patients younger than 50 years with IBS symptoms but no alarm features do not require routine colonic imaging. However, patients aged > 50 years (45 years in African Americans) should follow expert recommendations for colonic imaging for colorectal cancer screeningCitation2,Citation38,Citation60 and those aged > 50 years with alarm features should undergo colonoscopy to rule out organic disease.Citation2

Patients with IBS-D and alarm features should be examined specifically for colorectal cancer and IBD and potentially undergo random mucosal biopsies to rule out microscopic colitis, which has a prevalence of 2.3% among patients with IBS-D.Citation2,Citation61 The prevalence of microscopic colitis is highly age-dependent as shown in a Swedish epidemiology study of 1,018 patients presenting with nonbloody diarrhea who underwent colonoscopy; 10% overall, but 20% of those >70 years, received a diagnosis of microscopic colitis.Citation62 Patients with IBS-C should be evaluated for mechanical obstruction, which can be done by colonoscopy, virtual colonography, or barium enema.Citation2 Upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsies can be considered to test for celiac disease or SIBO in patients with laboratory or stool findings suggestive of malabsorption.Citation2

Newer, innovative tests for IBS

Several noninvasive diagnostic approaches were investigated for their ability to discriminate IBS from non-IBS disorders. Although more data are needed,Citation45,Citation48 these tests show potential as adjuncts to traditional diagnostic methods in IBSCitation33,Citation63 and may reduce unnecessary testing in clinical practice.Citation33,Citation45,Citation46

Examination of stool forms

Pimentel et alCitation45 evaluated the variations in frequency and consistency of bowel habits over time to distinguish diarrhea secondary to IBS from diarrhea associated with active celiac disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease. The basis for this testing is that patients with IBS-D, whose bowel function varies with changes in neuromuscular function, will more likely experience irregular bowel function and stool form than those with non-IBS causes of diarrhea. Sixty-two IBS-D patients and 37 non-IBS patients (UC, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease) completed a questionnaire on their bowel habits and stool forms during the preceding week. More IBS than non-IBS patients reported daily variations in stool form and frequency of bowel habits (79% vs 35%; P < 0.00001).Citation45 Further, 81% of IBS patients and 41% of those without IBS reported having at least three stool forms per week; the difference of three stool forms per week has a sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 84% in differentiating IBS.Citation45 The success of this simple tool in distinguishing between IBS and non-IBS diarrheal disease may help avoid unnecessary diagnostic testing.Citation45

Fecal markers

Increasing evidence supports the utility of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin in differentiating between IBD and IBS because these markers can identify active intestinal inflammation in IBD.Citation23,Citation48,Citation63–Citation65 Easily measured in feces, calprotectin and lactoferrin are stable, neutrophil-derived proteins that increase in concentration in response to leukocyte migration into the gut.Citation48,Citation64,Citation66

Tibble et alCitation46 examined the diagnostic efficacy of fecal calprotectin in 602 patients referred to a gastroenterology clinic. With a cutoff value of 10 mg/L, calprotectin had an 89% sensitivity and a 79% specificity for organic disease (ie, IBD) with an OR of 27.8 (95% CI: 17.6–43.7; P < 0.0001). Other investigators demonstrated similar diagnostic utility of these fecal markers to differentiate active IBD from inactive disease and from IBS.Citation64,Citation65 Schoepfer et alCitation23 prospectively found fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin levels in patients with IBD to be over the levels in patients with IBS and in healthy controls, but did not differ between IBS patients and healthy controls. Although the elevated levels of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are potentially valuable when screening for intestinal inflammation and discriminating between organic and functional diseases,Citation46,Citation48 neither the cause of the inflammatory process leading to the elevations can be discerned with these markers nor are the elevations able to “rule in” a diagnosis of IBS, given that differences between IBS and healthy controls are not significant.

Serologic markers

A number of altered physiological pathways have been identified in patients with IBS. The major pathogenic processes include altered gut motility and visceral hypersensitivity, which are believed to be due to the dysregulation of brain–gut axis pathways,Citation67 immune dysregulation in the GI tract,Citation68 altered gut flora,Citation2,Citation54,Citation56,Citation69 and complex interactions between neuronal and hormonal factors.Citation33 These alterations have prompted investigations of IBS biomarkers that may help elucidate the pathophysiology of the disorderCitation68 and aid in the diagnosis of the disease.Citation33

Lembo et alCitation33 described a panel of 10 serum biomarkers that may be useful to help differentiate IBS from non-IBS disease and healthy controls. This biomarker panel was derived from a literature review, which identified >60,000 possible biomarkers common to IBS and other GI diseases (both functional and organic) and part of the differential diagnosis in suspected IBS. Subsequently, this group of biomarkers was further refined to 140 biomarkers by identifying those that were common across multiple pathways, those that were serum based, and those for which assays were commercially available. Assays of these 140 biomarkers in IBS and control samples resulted in significant median differences in 16 biomarkers. Expression values of these 16 biomarkers were then evaluated in >300,000 algorithms, ultimately identifying 10 biomarkers, the combined performance of which provided the greatest accuracy in distinguishing IBS patients from non-IBS patients. The panel includes interleukin-1β, growth-related oncogene-α, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, antihuman anti-tTG, tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, antibody to bacterial flagellin (anti-CBir1), anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA-IgA), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA).Citation33 Six of these biomarkers have been associated with metabolic dysregulation in IBS, whereas others (ASCA, ANCA, and anti-CBir1) have typically been associated with IBD. Notably, one study demonstrated elevated levels of anti-CBir1 in a subset of patients with postinfectious IBS, presumably the result of bacterial infection and immune system activation.Citation70 The role of inflammatory processes in IBS and concomitant changes in biomarker expression need to be more fully evaluated, especially as they relate to potential changes over the course of the disease. Likewise, anti-tTG is a serum antibody known to be highly specific for only celiac disease.

After the biomarkers were identified, a predictive modeling tool was used to discern patterns of serum concentrations that best differentiated IBS patients from those with non-IBS GI disease (IBD, non-IBS functional GI disorders, and celiac disease) and healthy controls in a training cohort of 1,205 patients.Citation33 This model was then validated in a different cohort of 516 patients with IBS or a non-IBS GI disease and healthy controls. The overall diagnostic accuracy of this test in differentiating IBS from non-IBS was 70% (sensitivity 50%, specificity 88%), and at a 50% IBS prevalence, the positive predictive value was 81% and the negative predictive value was 64%, leading investigators to conclude that a positive test result can help confirm a suspicion of IBS although the sensitivity is insufficient for a negative test to reliably exclude the diagnosis.Citation33 Although not appropriate for use as a single diagnostic tool, this biomarker panel may be a cost-effective adjunct to traditional diagnostic methods in an overall work-up of IBS.Citation33 A systematic review and a meta-analysis examining various diagnostic criteria in IBS have reported that the Manning, Kruis, and Rome I criteria have similar positive and negative likelihood ratios of predicting an IBS diagnosis in comparison to the 10-biomarker diagnostic panel.Citation31,Citation71 As the only serologic test that “rules in” IBS, the panel may provide optimal utility early in the disease course, avoiding more expensive and invasive testing, introducing greater confidence in a “correct” diagnosis, and allowing earlier initiation of an appropriate treatment plan. As the biomarker test evolves through scientific and technologic advances, sensitivity and specificity should improveCitation33 and lead to better clinical trials and quality of life for patients with IBS.

Conclusion

The substantial human and economic cost associated with IBS necessitates development of efficient diagnostic and management strategies.Citation37 Although among the most common disorders in gastroenterology and primary care practices, IBS continues as a substantial diagnostic challenge. A lack of confidence in symptom-based diagnosis, a broad differential diagnosis, patient misconceptions and expectations, and medicolegal concerns about missing organic disease may all contribute to unnecessary and costly diagnostic testing.Citation2,Citation27,Citation34 Nevertheless, the diagnosis of IBS is often missed or delayed. Innovative diagnostic tests, such as examination of stool forms, fecal markers of inflammation, and IBS serology, offer promise as noninvasive, cost-efficient adjuncts to traditional diagnostic methods, particularly early in the disorder.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank John Simmons, MD, for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Writing support was provided with funding from Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.

Disclosure

Dr Burbige has served as a speaker and consultant for Prometheus Laboratories and as a speaker for Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- LongstrethGFThompsonWGCheyWDHoughtonLAMearinFSpillerRCFunctional bowel disordersGastroenterology200613051480149116678561

- American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel SyndromeAn evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol2009104Suppl 1S1S35

- CashBDCheyWDIrritable bowel syndrome – an evidence-based approach to diagnosisAliment Pharmacol Ther200419121235124515191504

- MayerEAClinical practice. Irritable bowel syndromeN Engl J Med2008358161692169918420501

- SerraJAzpirozFMalageladaJRImpaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndromeGut2001481141911115817

- CamilleriMEvolving concepts of the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome: to treat the brain or the gut?J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200948Suppl 2S46S4819300123

- NozuTKudairaMKitamoriSUeharaARepetitive rectal painful distention induces rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndromeJ Gastroenterol200641321722216699855

- SpillerRCJenkinsDThornleyJPIncreased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndromeGut200047680481111076879

- SaitoYASchoenfeldPLockeGRIIIThe epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol20029781910191512190153

- HunginAPChangLLockeGRDennisEHBarghoutVIrritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impactAliment Pharmacol Ther200521111365137515932367

- AndrewsEBEatonSCHollisKAPrevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large Web-based surveyAliment Pharmacol Ther2005221093594216268967

- MinochaAJohnsonWDAbellTLWigingtonWCPrevalence, sociodemography, and quality of life of older versus younger patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based studyDig Dis Sci200651344645316614950

- DrossmanDACamilleriMMayerEAWhiteheadWEAGA technical review on irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology200212362108213112454866

- American Gastroenterological AssociationThe Burden of Gastrointestinal DiseasesBethesda, MDAmerican Gastroenterological Association2001

- LongstrethGFYaoJFIrritable bowel syndrome and surgery: a multivariable analysisGastroenterology200412671665167315188159

- DeanBBAguilarDBarghoutVImpairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBSAm J Manag Care2005111 SupplS17S2615926760

- El-SeragHBOldenKBjorkmanDHealth-related quality of life among persons with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic reviewAliment Pharmacol Ther20021661171118512030961

- GralnekIMHaysRDKilbourneANaliboffBMayerEAThe impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of lifeGastroenterology2000119365466010982758

- International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersIBS in the Real World Survey. Summary findings. International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Available from: http://about-constipation.org/pdfs/IBSRealWorld.pdf. Accessed Aug 19, 2010.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Digestive Diseases Information ClearinghouseIrritable bowel syndrome Available from: http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/ibs/index.htm. Accessed Aug 19, 2010.

- CamilleriMChoiMGReview article: irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther19971113159042970

- FrissoraCLKochKLSymptom overlap and comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other conditionsCurr Gastroenterol Rep20057426427116042909

- SchoepferAMTrummlerMSeeholzerPSeibold-SchmidBSeiboldFDiscriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodiesInflamm Bowel Dis2008141323917924558

- WhiteheadWEPalssonOJonesKRSystematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications?Gastroenterology200212241140115611910364

- AaronLABurkeMMBuchwaldDOverlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorderArch Intern Med2000160222122710647761

- FordACVeldhuyzen van ZantenSJRodgersCCTalleyNJVakilNBMoayyediPDiagnostic utility of alarm features for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysisGut200857111545155318676420

- LongstrethGFBurchetteRJFamily practitioners’ attitudes and knowledge about irritable bowel syndrome: effect of a trial of physician educationFam Pract200320667067414701890

- SpiegelBMDo physicians follow evidence-based guidelines in the diagnostic work-up of IBS?Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol20074629629717541444

- FrancisCYDuffyJNWhorwellPJMartinDFDoes routine abdominal ultrasound enhance diagnostic accuracy in irritable bowel syndrome?Am J Gastroenterol1996917134813508677992

- CashBDSchoenfeldPCheyWDThe utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol200297112812281912425553

- FordACTalleyNJVeldhuyzen van ZantenSJVakilNBSimelDLMoayyediPWill the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms?JAMA2008300151793180518854541

- LacyBERosemoreJRobertsonDCorbinDAGrauMCrowellMDPhysicians’ attitudes and practices in the evaluation and treatment of irritable bowel syndromeScand J Gastroenterol200641889290216803687

- LemboAJNeriBTolleyJBarkenDCarrollSPanHUse of serum biomarkers in a diagnostic test for irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther200929883484219226291

- CasidayREHunginAPCornfordCSde WitNJBlellMTPatients’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: symptoms and treatment more important than explaining aetiologyFam Pract2009261404719011174

- HalpertADaltonCBPalssonOWhat patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National Survey on Patient Educational Needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ)Am J Gastroenterol200710291972198217488254

- LacyBEWeiserKNoddinLIrritable bowel syndrome: patients’ attitudes, concerns and level of knowledgeAliment Pharmacol Ther200725111329134117509101

- SpiegelBMGralnekIMBolusRIs a negative colonoscopy associated with reassurance or improved health-related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome?Gastrointest Endosc200562689289916301033

- LiebermanDAHolubJEisenGKraemerDMorrisCDUtilization of colonoscopy in the United States: results from a national consortiumGastrointest Endosc200562687588316301030

- ManningAPThompsonWGHeatonKWMorrisAFTowards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowelBr Med J197826138653654698649

- KruisWThiemeCWeinzierlMSchusslerPHollJPaulusWA diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic diseaseGastroenterology1984871176724251

- DrossmanDAThompsonWGTalleyNJIdentification of sub-groups of functional gastrointestinal disordersGastroenterology International199034159172

- DrossmanDAReview article: an integrated approach to the irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther199913Suppl 231410429736

- VannerSJDepewWTPatersonWGPredictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol199994102912291710520844

- RubinGDeWNMeineche-SchmidtVSeifertBHallNHunginPThe diagnosis of IBS in primary care: consensus development using nominal group techniqueFam Pract200623668769217062586

- PimentelMHwangLMelmedGYNew clinical method for distinguishing D-IBS from other gastrointestinal conditions causing diarrhea: the LA/IBS diagnostic strategyDig Dis Sci201055114514919169820

- TibbleJASigthorssonGFosterRForgacsIBjarnasonIUse of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal diseaseGastroenterology2002123245046012145798

- PoullisAFosterRMendallMAFagerholMKEmerging role of calprotectin in gastroenterologyJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200318775676212795745

- KaneSVSandbornWJRufoPAFecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammationAm J Gastroenterol20039861309131412818275

- TolliverBAHerreraJLDiPalmaJAEvaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol19948921761788304298

- HammLRSorrellsSCHardingJPAdditional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteriaAm J Gastroenterol19999451279128210235207

- SaadRJCheyWDBreath tests for gastrointestinal disease: the real deal or just a lot of hot air?Gastroenterology200713361763176618054546

- SuarezFLSavaianoDALevittMDA comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intoleranceN Engl J Med19953331147776987

- Di StefanoMMiceliEMazzocchiSTanaPMoroniFCorazzaGRVisceral hypersensitivity and intolerance symptoms in lactose malabsorptionNeurogastroenterol Motil2007191188789517973635

- PimentelMParkSMirochaJKaneSVKongYThe effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2006145855756317043337

- PimentelMChowEJLinHCEradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol200095123503350611151884

- LinHCSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndromeJAMA2004292785285815316000

- PosserudIStotzerPOBjornssonESAbrahamssonHSimrenMSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndromeGut200756680280817148502

- FordACCheyWDTalleyNJMalhotraASpiegelBMMoayyediPYield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysisArch Intern Med2009169765165819364994

- MacIntoshDGThompsonWGPatelDGBarrRGuindiMIs rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome?Am J Gastroenterol19928710140714091415096

- PignoneMRichMTeutschSMBergAOLohrKNScreening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med2002137213214112118972

- NojkovBRubensteinJHCashBDThe yield of colonoscopy in patients with non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): results from a prospective, controlled US trial [abstract 178]Gastroenterology2008134Suppl 1(60)A30

- OlesenMErikssonSBohrJJarnerotGTyskCMicroscopic colitis: a common diarrhoeal disease. An epidemiological study in Orebro, Sweden, 1993–1998Gut200453334635014960513

- TibbleJTeahonKThjodleifssonBA simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s diseaseGut200047450651310986210

- LanghorstJElsenbruchSKoelzerJRuefferAMichalsenADobosGJNoninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indicesAm J Gastroenterol2008103116216917916108

- SilbererHKuppersBMickischOFecal leukocyte proteins in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndromeClin Lab2005513–411712615819166

- GuerrantRLAraujoVSoaresEMeasurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytesJ Clin Microbiol1992305123812421583125

- American Gastroenterological AssociationAmerican Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology200212362105210712454865

- AerssensJCamilleriMTalloenWAlterations in mucosal immunity identified in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20086219420518237869

- KassinenAKrogius-KurikkaLMakivuokkoHThe fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjectsGastroenterology20071331243317631127

- SchoepferAMSchafferTSeibold-SchmidBMullerSSeiboldFAntibodies to flagellin indicate reactivity to bacterial antigens in IBS patientsNeurogastroenterol Motil2008201110111818694443

- FordAC10-biomarker algorithm to identify irritable bowel syndrome: author’s replyAliment Pharmacol Ther2009301959619566909