Abstract

Purpose

The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori gastritis has been declining, whereas H. pylori-negative gastritis has become more common. We evaluated chronic gastritis in children with regard to H. pylori status and celiac disease (CD).

Patients and methods

Demographic, clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of children who underwent elective esophagogastroduodenoscopy were reviewed retrospectively. Gastric biopsies from the antrum and corpus of the stomach were graded using the Updated Sydney System. H. pylori presence was defined by hematoxylin and eosin, Giemsa, or immunohistochemical staining and urease testing.

Results

A total of 184 children (61.9% female) met the study criteria with a mean age of 10 years. A total of 122 (66.3%) patients had chronic gastritis; 74 (60.7%) were H. pylori-negative. Children with H. pylori-negative gastritis were younger (p=0.003), were less likely to present with abdominal pain (p=0.02), and were mostly of non-Arabic origin (p=0.011). Nodular gastritis was found to be less prevalent in H. pylori-negative gastritis (6.8%) compared with H. pylori-positive gastritis (35.4%, p<0.001). The grade of mononuclear infiltrates and neutrophil density was more severe in the H. pylori-positive group (p<0.001). Pan-gastritis and lymphoid follicles were associated most commonly with H. pylori. Although less typical, lymphoid follicles were demonstrated in 51.3% of H. pylori-negative patients. The presence or absence of CD was not associated with histologic findings in H. pylori-negative gastritis.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that lymphoid follicles are a feature of H. pylori-negative gastritis in children independent of their CD status.

Introduction

The presence of Helicobacter pylori entails a 10%–15% lifetime risk of complications. Early acquisition of H. pylori can lead to accelerated development of preneoplastic gastric lesions and to an increased risk of gastric carcinomas.Citation1–Citation4

There are very little data regarding the risk factors as well as the clinical and histologic characteristics of non-H. pylori-induced chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (IM) in the pediatric literature, as opposed to H. pylori-positive (Hp+) gastritis. H. pylori-negative (Hp−) chronic gastritis has multiple etiologies: non-H. pylori gastric microorganisms; autoimmune gastritis; allergic and eosinophilic gastritis; lymphocytic gastritis due to other diseases, such as Crohn’s disease. Gastritis because of external causes, such as drugs and alcohol, does not have roles in pediatric populations.Citation5

In a prospective study, Nordenstedt et al reported gastritis in 200 (40.7%) adults, of whom 41 (20.5%) had Hp− gastritis and 73.2% had chronic gastritis.Citation6 The prevalence of Hp− gastritis in children living in North America is 46%–63%.Citation7 Recently, Kara et al reviewed the histology of cells obtained from upper-endoscopy procedures in children. From 358 procedures, 144 (40%) children had Hp− gastritis.Citation8 Biopsies from the antrum of the stomach from 82 children with chronic gastritis (36 Hp+, 46 Hp−) living in Mexico revealed atrophy and follicular disease more frequently in Hp+ biopsies, whereas IM showed no significant correlation with H. pylori status.Citation9 Elitsur et al reported a higher prevalence of Hp− gastritis in children (~50%) compared with adults (~20%).Citation7

Here, we attempted to evaluate the prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlations of chronic gastritis and IM in childhood in a large cohort. We also tried to determine the relationship between H. pylori infection and celiac disease (CD) to pathologic abnormalities.

Patients and methods

Ethical approval of the study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Assaf Harofeh Medical Center (Tzrifin, Israel). Written informed consent was waived for this study because of the retrospective nature of the study. Patient data confidentiality was never broken because all data were anonymously gathered.

Study design and study cohort

We evaluated (retrospectively) clinical data and biopsy specimens from all patients aged <18 years who had gastric biopsies at our medical center over a 12-month period. Inclusion criteria were: children aged between 2 and 18 years who had ≥5 biopsies obtained routinely during endoscopy (two from the antrum and two from the corpus of the stomach) for histologic study. Another biopsy from the antrum was evaluated for H. pylori using a rapid urease test (Pronto Dry; Gastrex, Paris, France). Exclusion criteria were: patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease, 4 weeks prior treatment with antibiotics, or 2 weeks with proton pump inhibitors.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

All endoscopies had been carried out by very experienced and highly qualified endoscopists using a FG-2490K or EG-29i10 video gastroscope (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopy was done under sedation. The endoscopic aspect of nodular gastritis was based on the military nodular appearance of the mucosa.Citation10

Histology

Four biopsy specimens (two from the antrum and two from the corpus of the stomach) were fixed in 4% neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Giemsa, and alcian blue at pH 2.5. The biopsies from these patients were reviewed and analyzed for gastritis, IM, and H. pylori. In the absence of H. pylori with chronic or chronic active gastritis upon H&E staining, immunohistochemical staining for H. pylori using polyclonal antibodies (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) was undertaken.

Definitions

“Chronic inflammation” was defined as >5 mononuclear cells per 100 epithelial nuclei in H&E-stained specimens.Citation11 The severity and activity of gastritis, the presence of H. pylori, H. pylori density, and IM were recorded using the criteria for visual analog scale set by the updated Sydney classification.Citation11 For statistical analyses, we condensed the gastritis scale into “chronic active” or “chronic inactive”, “antrumpredominant” or “corpus-predominant”, “Hp+ gastritis”, and “Hp− gastritis”. H&E-stained specimens were evaluated for epithelial damage, mucous depletion, and erosions; atrophy, intestinal, pseudopyloric, or pancreatic metaplasia; and lymphoid follicles. CD was diagnosed according to the latest criteria set by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition: positive serology and some evidence of villous atrophy.Citation12 Patients with potential CD (positive serology with Marsh 1/Marsh 2 lesions) were excluded. Gastritis was considered to be H. pylori− if no H. pylori organisms were seen in H&E and immunohistochemical staining and negative rapid urease test.

“Ethnicity” was defined as the country of origin of the child’s parents and grandparents. Participants were classified into Sepharadi (Asia/Africa/Middle East), Ashkenazi (Western Europe/America), formerly Soviet Union, Ethiopia, and Arabs.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS v21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The Mann–Whitney U-test or Student’s t-test was used for analyses of ordinal or continuous variables. The c2 test was used to analyze categorical variables. The Fisher’s exact test was used if the conditions for using the c2 test were not met. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

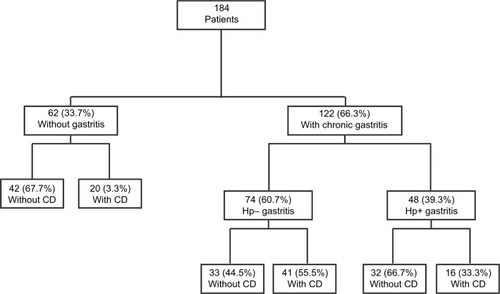

Two-hundred and sixty-one children underwent EGD from July 2014 to August 2015. Thirty patients who had undergone urgent EGD (11 with inflammatory bowel disease and 5 with other gastrointestinal diseases) and 31 children with missing or incomplete biopsies were excluded. Thus, 184 patients remained for further evaluation. Biopsies with evident chronic gastritis were identified from 122 patients (66.3%). Histopathologic examination of the stomach was normal, without gastritis, in 62/184 (33.7%) patients. Only 48 (39.3%) of the 122 patients with chronic gastritis were associated with H. pylori infection, whereas the remaining 74 children had Hp− gastritis. According to the Marsh classification,Citation12 16 (33.3%) of the 48 patients with Hp+ gastritis had evidence of CD compared with 41 children (55.5%) diagnosed with CD in the Hp− gastritis group (p=0.016) ().

Figure 1 Study patients with gastritis according to their H. pylori and CD status.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at presentation are summarized in . There were more females in “gastritis” and “nongastritis” groups. Distribution of the mixed ethnic group was more common in the nongastritis group (33.3% vs 19.7%, p=0.045), whereas more children of Ethiopian origin were in the gastritis group (6.8% vs 0%, p=0.038). The only significant difference in clinical findings was a higher prevalence of iron-deficiency anemia (p=0.013) and short stature (p=0.008) among the gastritis group.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without gastritis

H. pylori infection was more common in children of Arab origin (p=0.011) and in older children (mean age of 11.6±4.1 vs 9.1±4.5 years compared with Hp− children). Abdominal pain was more prevalent among patients with Hp+ gastritis (p=0.020) with no differences in other symptoms.

Demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ with regard to the presence or absence of H. pylori among patients with CD. No significant difference was noted in the ethnic background symptoms or in the use of proton pump inhibitors. CD patients without H. pylori were younger than CD patients with H. pylori (6.7±3.3 vs 9.6±4, p=0.006).

Gastritis and H. pylori

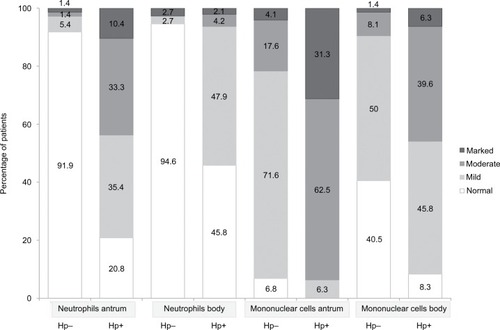

Nodular gastritis occurred in 35.4% of patients with Hp+ gastritis and in 6.8% of children with Hp− chronic gastritis (p<0.001). The presence of H. pylori was correlated positively with endoscopic nodular gastritis in patients with or without CD. None of the children with CD and Hp− gastritis had nodular gastritis upon endoscopy. Hp+ gastritis involved the entire stomach in 95.8% of children, whereas 50% of children without H. pylori had pan-gastritis. Eighty-three percent of patients with gastritis on account of H. pylori had chronic active gastritis, as opposed to 9.5% of patients without H. pylori (p<0.001) with a specificity of 90.5%, a sensitivity of 83.3%, a negative predictive value of 89.3% and a positive predictive value of 85.1%. Histopathologicgraded variables are presented in . Patients with H. pylori had more severe gastritis, and this was the trend in the antrum and corpus.

Figure 2 Histological characteristics of graded variables of patients according to their H. pylori status.

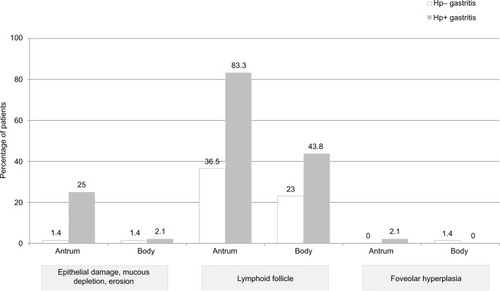

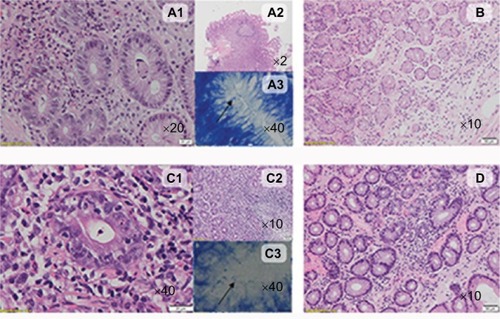

The histopathologic nongraded variables evaluated in our patients, and their relationship with H. pylori, are presented in . Atrophic gastritis, intestinal, pseudopyloric, or pancreatic metaplasia, or hyperplasia of endocrine cells was not detected in any patient. Lymphoid follicles in the antrum and corpus were correlated positively with H. pylori regardless of the presence of CD. However, we found a high prevalence of lymphoid follicles in Hp− gastritis in CD (46.3%) or non-CD (57.5%) patients. Epithelial damage, mucous depletion, and erosions were much more common in Hp+ patients (). The typical histologic characteristics of Hp+ gastritis and Hp-gastritis are demonstrated in .

Figure 3 Histological characteristics of nongraded variables of patients according to their H. pylori status.

Figure 4 The typical histological characteristics of Hp+ gastritis and Hp− gastritis in celiac and nonceliac patients.

Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Hp+, H. pylori positive, Hp−, H. pylori negative; HPF, high-power field; LPF, low-power field.

Hp–gastritis

Comparison between children with Hp− gastritis with no CD and children with Hp− gastritis with CD revealed several differences. As expected, patients with CD-associated Hp− gastritis had a lower body mass index (15.8±2.44 vs 19.5±4.83 kg/m2, p<0.001) and presented more frequently with short stature (19.5% vs 3%, p=0.031). However, abdominal pain was less common in this group (31.7% vs 66.7%, p=0.003). More children of Ethiopian origin and fewer of mixed ethnic origin were in the non-CD Hp− gastritis group (). Endoscopic features such as nodular gastritis were more prominent in the non-CD Hp− gastritis group (p=0.010), but the histopathologic characteristics of gastritis between these groups were not significantly different ().

Table 2 Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with nonceliac Hp− gastritis and patients with CD-associated Hp− gastritis

Discussion

In our study, H. pylori was found in 26% of participants with gastritis who had undergone EGD. Our results correlate with recent data suggesting a prevalence of seropositivity of 30%−45.2% in children living in Israel.Citation13,Citation14 This is significantly higher than that reported in children in the USA (3%–7%).Citation15 We also found a higher prevalence (60.7%) of gastritis without H. pylori than observed previously in children from Turkey (40%), Mexico (44%), and the USA (50%).Citation7–Citation9 Studies in adults have shown a much lower proportion of Hp− gastritis.Citation6,Citation7

Though our study was retrospective, four biopsies (two from the antrum and two from the corpus) had been taken from each stomach and slides were evaluated by a lone expert pathologist, as recommended by Sydney guidelines.Citation11 Histologic comparison between the two types of gastritis revealed pan-gastritis, active gastritis, lymphoid follicles, mucous depletion, erosions, and surface epithelial damage to be significantly more common in the Hp+ group. There was no pathologic finding of IM in our patients, confirming studies in children with Hp+ gastritis that showed an absence of IM or low prevalence of IM in such cases.Citation16

H. pylori infection promotes an immunologic response that leads to the development of lymphoid aggregates and lymphoid follicles with germinal centers.Citation8,Citation17 Genta et al stated that lymphoid follicles in a gastric biopsy specimen are associated with chronic active gastritis and provide a useful marker for H. pylori infection.Citation18 Moreover, these follicles are thought to represent the pathophysiologic substrate for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-lymphomas.Citation19,Citation20 In our study, lymphoid follicles were associated most commonly with H. pylori infection, but lymphoid follicles were also present in 51.3% of patients with evidence of Hp− gastritis. Our results are in accordance with a study that also detected lymphoid follicles in almost half of cases with Hp− gastritis and idiopathic gastritis,Citation21 but are not in accordance with two more recent studies which reported that lymphoid follicles are relatively rare (prevalence of 4.1% in Houston, USACitation22 or 14% in Tunis, TunisiaCitation23 in Hp− gastritis). Lymphoid follicles in gastric biopsies from children, while of potential pathophysiologic importance, are of uncertain clinical importance and raise important issues: 1) should we treat young patients with lymphoid aggregates differently; 2) should we carry out a different type of surveillance in these patients?

The increased prevalence of Hp− chronic gastritis may be related to several variables. It has been suggested that Hp− gastritis comprises mainly “missed” H. pylori infections.Citation24 However, recently Genta et al showed that Hp− gastritis may occur only in 1.1% of patients with chronic inactive gastritis, which is a distinct entity according to nosologic and epidemiologic criteria.Citation25 It has also been suggested that chronic gastritis can be caused by viruses such as the Epstein–Barr virusCitation26 or non-H. pylori strains. A substantial number of novel Helicobacter spp. have been described. A high incidence of gastric H. pylori infection has been described in China, and multiple case reports have detailed involvement of enterohepatic Helicobacter spp. (especially Helicobacter cinaedi) in a wide range of diseases.Citation27 These strains are susceptible to sampling error with high rates of false-negative results which are probably due to the focal and decreased colonization of bacteria in the gastric mucosa.Citation28

Limitations

Our study had three main limitations. First, it was a retrospective cohort, so other infectious etiologies for gastritis (as well as autoimmune gastritis) were not excluded fully. Second, our sampling methods were inadequate to judge the area involved. Third, the high proportion of children with lymphoid follicles but no H. pylori may have reflected a selection bias because our center serves a tertiary center for CD diagnosis. Indeed, the high proportion of children who had CD (57 of 122 [46.7%] of gastritis cases) suggests that this may be the case. Nevertheless, CD was not associated with chronic gastritis, and there were no histopathologic differences between CD-associated Hp− gastritis and non-CD-associated Hp− gastritis. Moreover, the prevalence of CD was correlated inversely with H. pylori, which indicates that H. pylori may reduce CD risk, as reported previously.Citation29 Nevertheless, the predominant histologic features in patients with Hp+ gastritis and CD were related to H. pylori, as manifested by chronic active gastritis with polymorphonuclear neutrophils, lymphoid follicles, and curved, rod-shaped bacteria.

Conclusion

Taken together, our results suggest that Hp− gastritis is a common phenomenon in children, alone or with CD, with a high prevalence of lymphoid follicles in the antrum or corpus of the stomach. The clinical relevance and prognosis of this finding are not known: Is it self-limiting or is further investigation warranted? Additional long-term follow-up studies in young patients with lymphoid follicles should help elucidate the significance of this finding. Such studies may also facilitate the identification, surveillance, and optimal treatment strategy for these young patients with chronic gastritis.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ParsonnetJThe incidence of Helicobacter pylori infectionAliment Pharmacol Ther199599Suppl 24551

- LeeYCChiangTHChouCKAssociation between Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysisGastroenterology201615051113112426836587

- VeneritoMNardoneGSelgradMRokkasTMalfertheinerPGastric cancer--epidemiologic and clinical aspectsHelicobacter201419Suppl 1323725167943

- CorreaPHuman gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process-First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer epidemiology and PreventionCancer Res19925224673567401458460

- SuganoKTackJKuipersEJKyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritisGut20156491353136726187502

- NordenstedtHGrahamDYKramerJRHelicobacter pylori-negative gastritis: prevalence and risk factorsAm J Gastroenterol20131081657123147524

- ElitsurYHelicobacter-negative gastritis: the pediatric perspectiveAm J Gastroenterol201310871182118323821004

- KaraNUrganciNKalyoncuDYilmazBThe association between Helicobacter pylori gastritis and lymphoid aggregates, lymphoid follicles and intestinal metaplasia in gastric mucosa of childrenJ Pediatr Child Health201450815

- Villarreal-CalderonRLuévano-GonzálezAAragón-FloresMAntral atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and preneoplastic markers in Mexican children with Helicobacter pylori–positive and Helicobacter pylori–negative gastritisAnn Diagn Pathol201483129135

- SokmensuerCOnalIKYeniovaOWhat are the clinical implications of nodular gastritis? Clues from histopathologyDig Dis Sci200954102150215419462235

- DixonMFGentaRMYardleyJHCorreaPClassification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994Am J Pathol1996201011611181

- HusbySKoletzkoSKorponay-SzabóIRESPGHAN Working Group on Coeliac Disease DiagnosisESPGHAN Gastroenterology CommitteeEuropean Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and NutritionEuropean society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201254113616022197856

- ZevitNLevyIShmuelyHSamraZYahavJAntibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Israeli childrenScand J Gastroenterol201045555055520199338

- MuhsenKCohenDSpungin-BialikAShohatTSeroprevalence, correlates and trends of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Israeli populationEpidemiol Infect201214071207121422014090

- ElitsurYPrestonDLHelicobacter-pylori negative gastritis in children - a new clinical enigmaDiseases201424301307

- WhitneyAEGuarnerJHutwagnerLGoldBDHelicobacter pylori gastritis in children and adults: comparative histopathologic studyAnn Diagn Pathol20004527928511073332

- StolteMEidtSLymphoid follicles in antral mucosa: immune response to Campylobacter pylori?J Clin Pathol198942121269126712613920

- GentaRMHamnerHWThe significance of lymphoid follicles in the interpretation of biopsy specimensArch Pathol Lab Med19921187740743

- Herrera-GoepfertRGarcia-MarcanoRZeichner-GanczIHelicobacter pylori and lymphoid follicles in primary gastric MALT-lymphoma in MexicoRev Invest Clin19964842612658916447

- NakamuraSMatsumotoTYeHHelicobacter pylori-negative gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. A clinicopathologic and molecular study with reference to antibiotic treatmentCancer2006107122770277817099876

- ZaitounAMThe prevalence of lymphoid follicles in Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis in patients with ulcers and non-ulcer dyspepsiaJ Clin Pathol19954843253297615851

- Rosas-BlumETatevianNHashmiSSRhoadsJMNavarroFNonspecific gastric inflammation in children is associated with proton pump inhibitor treatment for more than 6 weeksFront Pediatr20142023

- Mazigh MradSAbidiKBriniIBoukthirSSammoudANodular gastritis: an endoscopic indicator of Helicobacter pylori infection in childrenTunis Med2012901178979223197056

- KissSZsiklaVFrankAWilliNCathomasGHelicobacter-negative gastritis: polymerase chain reaction for Helicobacter DNA is a valuable tool to elucidate the diagnosisAliment Pharmacol Ther201643892493226890160

- GentaRMSonnenbergAHelicobacter-negative gastritis: a distinct entity unrelated to Helicobacter pylori infectionAliment Pharmacol Ther201541221822625376264

- GentaRMLashRHHelicobacter pylori-negative gastritis: seek, yet ye shall not always findAm J SurgPathol2010348e25e34

- FlahouBHaesebrouckFSmetAYonezawaHOsakiTKamiyaSGastric and enterohepatic non-Helicobacter pylori HelicobactersHelicobacter201318Suppl 16672

- GentaRMLashRHEditorial: no bugs bugging you? Emerging insights into Helicobacter-negative gastritisAm J Gastroenterol20131081727423287944

- LebwohlBBlaserJMLudvigssonJFGreenPHRSonnenbergARAGentaRMDecreased risk of celiac disease in patients with Helicobacter pylori colonizationAm J Epidemiol2013178121721173024124196