Abstract

Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) is a recently described, rare gastric polyposis syndrome. It is characterized by extensive involvement of the fundus and body of the stomach with fundic gland polyps sparing the antrum and lesser curvature, an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance, and a significant predisposition for the development of gastric adenocarcinoma. Due to the recent discovery of APC promotor IB mutations (c.-191T>C, c.-192A>G, and c.-195A>C), which reduce binding of the transcription factor Yin Yang 1 (YY1) and transcriptional activity of the promotor, as its underlying genetic perturbation, GAPPS has been added to the growing molecular class of APC-associated disorders. Recent reports on family members afflicted by gastric polyposis due to GAPPS have described the development of metastatic cancer or the presence of invasive gastric adenocarcinoma in total gastrectomy specimens after variable periods of endoscopic surveillance emphasizing the need for an improved understanding of the to-date poorly characterized natural history of the syndrome. There are, however, currently no guidelines on screening, timing of prophylactic gastrectomy, or endoscopic surveillance for GAPPS available. In this review, we summarize the clinical, pathological, and genetic aspects of GAPPS as well as management approaches to this rare cancer predisposition syndrome, highlighting the need for early recognition, a multidisciplinary approach, and the creation of prospective family registries and consensus guidelines in the near future.

Diagnosis

In 2012, Worthley et al reported in three families the clinicopathological features of a novel gastric polyposis syndrome termed gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS).Citation1 The authors described in a large Australian family and two smaller families from USA and Canada that multiple family members afflicted by fundic gland polyposis (>100 polyps carpeting the fundus and body of the stomach sparing the antrum and lesser curvature in the index proband) multiple cases of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach arising in regions of fundal gland polyposis with high-grade dysplasia and adenomatous polyps. Within the same issue, researchers from Japan described two additional families with a similar phenotype.Citation2 Genetic testing for known gastrointestinal (GI) polyposis and gastric cancer predisposition syndromes was negative. Together with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, the authors proposed a series of endoscopic and pathological criteria for the diagnosis of GAPPS, which are listed in .Citation1

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for GAPPS

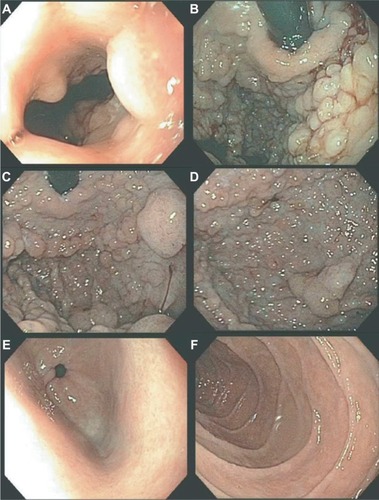

The initial endoscopic appearance of massive gastric polyposis of family members afflicted by GAPPS can resemble polyposis as a part of other gastric or GI polyposis syndromes. shows the pathognomonic lack of involvement of the antrum by fundic gland polyps (FGPs) on upper endoscopy in GAPPS, which can facilitate differential diagnosis to other GI polyposis syndromes. Generous biopsy sampling for an accurate histopathological diagnosis of the encountered lesions is paramount. In addition, in view of the overlapping phenotype with other GI polyposis syndromes, the criteria proposed by Worthley et al require the exclusion of other heritable gastric polyposis syndromes.Citation1 These should include MUTYH-associated polyposis (due to germline variants in the MUTYH gene; GI phenotype of multiple adenomatous colon polyps with greatly increased lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, followed by duodenal polyps and elevated duodenal cancer risk), juvenile polyposis syndrome (mutations in the BMPR1A or SMAD4 genes; multiple initially benign hamartomatous juvenile polyps across the GI tract with colorectal cancer the most common type of cancer), Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (loss of tumor suppressor STK1 [LKB1], hamartomatous polyps in the GI tract, elevated cancer risk in many other organs), and Cowden syndrome (loss of tumor suppressor PTEN; hamartomatous polyps, colorectal cancer most frequent GI cancer; breast, thyroid, and endometrial cancers and extraintestinal manifestations). lists cancer manifestations and initial phenotypes of common hereditary GI polyposis syndromes in comparison to the clinicopathological phenotype of GAPPS. To rule out germline variants associated with other gastric polyposis syndromes, commercially available multi-cancer gene panels for genetic testing are available, which include above polyposis-disposition genes and in addition can capture variants associated with known hereditary gastric cancer predisposition syndromes, which include CDH1 (hereditary diffuse gastric cancer [HDGC]), CTNNA1 (HDGC), TP53 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome), MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6 (Lynch syndrome).Citation3 Panel testing should follow current guidelines established by the American College of Medical Genetics and American Society of Clinical Oncology including ethical and policy issues in the genetic testing and screening of children.Citation4–Citation7

Figure 1 Endoscopy findings of gastric polyposis due to GAPPS.

Abbreviation: GAPPS, gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach.

Table 2 Hereditary GI polyposis syndromes

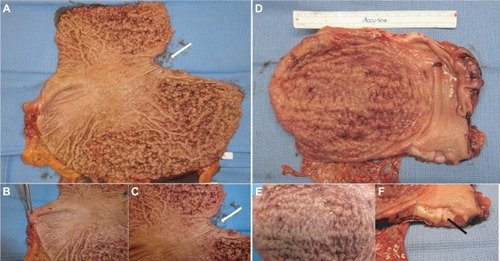

While awaiting results of genetic testing, the initial clinicopathological information from the proband can be used to aid differential diagnosis of other gastric polyposis syndromes: for example, hamartomatous polyps in Peutz– Jeghers, juvenile polyposis, or Cowden syndrome are distinct from FGPs with dysplasia due to their disorganized growth of tissue and initially benign character. However, securing a diagnosis of the underlying GI polyposis syndrome based on morphological characteristics of gastric polypectomy specimens alone is unlikely; for example, histopathological differences of gastric hamartomatous polyps among GI polyposis syndromes are difficult to diagnose, have a low diagnostic accuracy (41% for juvenile polyposis and 54% for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), and in general, do not allow to distinguish the underlying genetic syndrome without any genetic or clinical corroboration.Citation8,Citation9 Distinctive features reported for Peutz–Jeghers polyps are a cytoarchitectural pattern of pits and glands grouped or packeted together with intervening septations of smooth muscle strands not connected to the muscularis mucosa and an unremarkable lamina propria mucosae, whereas juvenile polyps more frequently have an overall disorganized pit and gland architecture with varying cystic glands and form spherical, club-shaped, or irregular villiform structures due to overgrowth of an edematous lamina propria with a mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate.Citation8,Citation9 Of note, hybrid polyps with varying degrees of hamartomatous and FGP features have been described in FGPs arising in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and attenuated FAP (AFAP) patients similarly underscoring the need of clinical and genetic corroboration to secure a diagnosis.Citation10,Citation11 Another entity with histopathological similarities to hamartomatous polyps are hyperplastic polyps where pits are connected to deeper portions in a linear trajectory with overall reduced architectural disorganization and varying degrees of stromal edema and inflammatory cell infiltrate.Citation8,Citation12 In contrast to GAPPS, MUTYH-associated polyposis is an autosomal recessive condition and is frequently associated with colonic polyposis, an exclusion criteria of GAPPS, with rare FGP involvement of the stomach.Citation9,Citation13 Other conditions with possible endoscopic resemblance of GAPPS are Ménétrier’s disease or hypoproteinemic hypertrophic gastropathy forming giant folds in the stomach lining, which are due to an overgrowth of mucous cells in the stomach wall. Cronkhite–Canada syndrome is another GI polyposis syndrome, which is characterized by protein-losing gastroenterocolopathy, which typically affects adults older than 50 years.Citation9,Citation14 Two-thirds of cases are reported from Japan with a male:female ratio of 2:1.Citation14 The histological hallmark of Cronkhite–Canada syndrome polyps resembles juvenile polyposis syndrome or hyperplastic polyps histologically characterized by expanded edematous lamina propria containing a predominantly mono-nuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate and tortuous, dilated to cystic glands/foveolae or crypts.Citation9,Citation15 Rather than occurring due to a hereditary predisposition, its etiopathogenesis is suspected to be of autoimmune origin.Citation16 Thus, in contrast to hereditary GI polyposis syndromes, the intestinal mucosa not involved by hamartomatous polyps is histologically not normal but shows lamina propria edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, and gland/crypt dilation.Citation9,Citation15 Clinical symptoms are driven by the GI symptoms of protein losing enteropathy or complications from hamartomatous polyps and include unique skin changes in the form of alopecia, hyperpigmentation, onychodystrophy (loss of fingernails), or the loss of taste (ageusia). Patients afflicted by Cronkhite–Canada syndrome carry a poor prognosis predominantly due to the difficult to control enteropathy. Linitis plastica, the sub-mucosal invasion of the diffuse form of gastric cancer, can predominantly involve the upper parts of the stomach and resemble “polypoid” enlargement of the stomach mucosa. shows total gastrectomies specimens of patients with florid gastric polyposis due to GAPPS and with linitis plastic due to HDGC involving the upper four-fifth of the stomach. The endoscopic appearance will depend on the extent of the polyposis, and in case of confluent, “carpet-like” involvement with limited disruption of the mucosa, the endoscopist may need to rely on the unique localization of the disease sparing the antrum and parts of the lower curvature and the histopathological diagnosis of FGPs on obtained biopsies to make the connection to GAPPS. Most reports on families afflicted by GAPPS report the presence of small fundal and body polyps (3–12 mm in size).

Figure 2 Gastric polyposis of the fundus and body of the stomach with pathognomonic sparing of the antrum and lesser curvature in a GAPPS proband with confirmed c.-191T>C APC gene promotor IB variant.

Abbreviations: GAPPS, gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach; HDGC, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.

An important other benign cause for gastric polyposis on endoscopy is the chronic use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) inducing oxyntic cell hyperplasia, glandular dilatations, and FGPs.Citation17,Citation18 In this case, endoscopy is recommended to be repeated after discontinuation and an appropriate off-treatment interval.Citation19 There is currently insufficient evidence to consider PPI therapy, a precipitating factor for the development of GAPPS. Serum gastrin levels, which are usually elevated in chronic PPI usage, were found to be normal in a few family members harboring the GAPPS phenotype arguing against a connection of PPI usage and GAPPS.Citation1 In contrast, there are several clinical observations, which imply gastric acid homeostasis and milieu in the natural history of FGPs in family members with a genetic predisposition to GI cancers: while chronic PPI usage has been observed as a risk factor for the development of FGPs, inversely Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infections have been reported to be negatively associated with the occurrence of FGPs both in healthy individuals and FAP patients.Citation20–Citation23 In family members afflicted by FAP, regression of FGPs has been described upon acquisition of H. pylori infection.Citation24 A possible protective role of H. pylori infection in the APC-related disorder GAPPS has also been suggested in the initially described large Australian GAPPS family when comparing H. pylori status of affected and unaffected family members (P=0.007).Citation1 Thus, in light of opposing associations of PPI usage and H. pylori infections on FGP incidence and in the absence of more natural history information derived from families afflicted by GAPPS, an approach of caution including early discontinuance of PPIs if clinically feasible and heightened surveillance of family members at risk for GAPPS with a history of chronic PPI usage appears to be the safest course of action. Discontinuation of PPI therapy and regression of FGPs may aid cases of diagnostic uncertainty where a florid polyposis picture with the unique sparing of the gastric antrum and lesser curvature with dysplasia on final pathology of generous biopsy sampling of FGPs is not present. FGPs due to PPI usage are significantly fewer, rarely harbor dysplasia, and do not spare the antrum. With the recent identification of APC promotor IB variants and ability to conduct timely germline genetic testing after genetic counseling stoppage and re-scoping of PPIs will rarely be required to secure the diagnosis and is not a must when other criteria have been met.

The possible association of H. pylori infection rates and the GAPPS phenotype including fundic gland polyposis was evaluated by Worthley et al in greater detail; in 27 family members with known H. pylori status, all evaluated family members with the GAPPS phenotype were negative for H. pylori (0/18) whereas four of the nine unaffected family members including obligate carriers (4/9) tested positive (P=0.007) suggesting a protective role of H. pylori in the development of GAPPS.Citation1 These findings mirror observations in FAP where patients with FGPs had lower rates of H. pylori compared to patients without FGPs (13% vs 67%).Citation22 In contrast, H. pylori infection and degree of atrophic gastritis were positively correlated with the incidence of gastric adenomas in FAP patients.Citation22 It is currently not known whether H. pylori infection rates are associated with gastric adenoma or adenocarcinoma in GAPPS or whether reduced H. pylori infection rates in patients with the GAPPS phenotype are a result of the disturbed intraluminal milieu due to fundic gland polyposis. Without a causative implication of H. pylori in GAPPS progression, clinical management of GAPPS patients is currently not affected by H. pylori status. In addition to the exclusion of other heritable gastric polyposis syndromes listed in , Worthley et al require as a part of their diagnostic criteria for GAPPS the endoscopic exclusion of colonic and duodenal polyposis as a part of FAP and AFAP. Fundal gland polyps are frequently present in FAP and AFAP, which are GI polyposis syndromes involving the colon and rectum but frequently harbor FGPs.

Histopathology

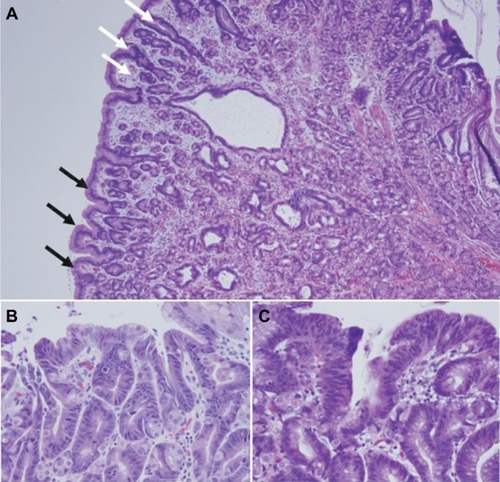

The polyposis and cancer predisposition syndrome with the greatest phenotypic overlap with GAPPS and most frequently cited as a diagnostic challenge are FAPs. Fundal gland polyps are one of the sentinel features of the GAPPS phenotype; FGPs most commonly occur as sporadic FGPs where they occur in small numbers, are usually small (<5 mm), are associated with chronic PPI therapy, and frequently harbor in the sporadic setting somatic CTNNB1 (β-catenin) mutations ().Citation25,Citation26 Sporadic FGPs rarely harbor dysplasia and are not connected to an increased risk of cancer.Citation27–Citation29 They are more frequently found in probands in their forties and fifties and more commonly in women.Citation20 Gastric FGPs are also a frequent phenotypic manifestation of the APC-associated disorders FAP and AFAP.Citation11,Citation30–Citation32 While widely varying rates of FGPs and fundal gland polyposis in individuals with FAP and AFAP have been reported, low-grade dysplasia is a common feature (up to 96%) of FAP-associated FGPs.Citation10,Citation30 FAP-associated FGPs preferentially harbor APC mutations and have an, albeit low, potential of malignant transformation toward adenocarcinoma of the stomach.Citation33–Citation35 While gastric carcinoma arising in FGPs of FAP patients has been described, the lifetime risk overall of gastric cancer in FAP patients from Western countries has been reported to be low (0.6%) but has been suggested to be rising.Citation33,Citation36,Citation37 Higher rates of gastric cancer have been described in FAP patients from countries with higher gastric cancer risks including Japan and Korea.Citation38,Citation39 summarizes common clinicopathological characterizations and clinical implications of FGPs detected within sporadic vs within polyposis-associated contexts. shows GAPPS-associated FGPs with low-grade and focal high-grade dysplasia.

Figure 3 Histopathology of fundic gland polyps in GAPPS.

Abbreviations: GAPPS, gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach; HDGC, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.

Table 3 Disease associations determine biological behavior of fundic gland polyps

A more systematic review on the histopathology of GAPPS has recently been released.Citation40 While limited to the review of multiple biopsies and gastrectomy specimens from the initially described, large Australian family, the detailed pathological and immunohistochemical review made important findings: hyperproliferative aberrant pits (HPAPs) were found to be the most frequent and most early histopathological abnormality in a wider histopathological spectrum of GAPPS.Citation40 HPAPs describe the disorganized hyper-proliferation of oxyntic glands of the stomach mucosa around gastric pits, which give rise to polypoid lesions. The finding of concomitant neoplastic elements in the form of FGPs with multifocal “flat” dysplasia, gastric adenomatous polyps, which were associated with gastric adenocarcinoma together with an immunohistochemical profile, in particular the gastric lineage marker MUC5AC shared by both precancerous lesions and adenocarcinoma, suggests a dysplasia– adenoma–adenocarcinoma sequence in the development of the malignant phenotype of GAPPS. Whether the absence or presence of some these precancerous lesions including their histopathological characteristics (HPAPs, FGPs with or without dysplasia, presence of adenomatous lesions) can be used to triage patients to undergo total gastrectomy vs endoscopic surveillance has to await the collection of larger case series. The concerns of adequate sampling via endoscopic biopsies in the face of hundreds of heterogenous polypoid lesions, which may include FGPs with different degrees of dysplasia, adenomas, or mixed histology polyps, pose significant challenges.

Gastric hyperplastic polyps (GHPs) account for the most frequent type of polyp in the stomach, and based on the above unique features of FGPs due to GAPPS, an expeditious distinction to GHPs based on clinicopathological criteria should be possible. GHPs more frequently occur as solitary lesions (65%–75%).Citation12,Citation41 Common sites include the antrum, and in more recent reports, the body of the stomach; however, GHPs can occur anywhere.Citation12,Citation41 GHPs are intimately linked to gastric inflammation and gastric mucosal injury with chronic gastritis (with or without H. pylori) being the most common (up to 85%).Citation12 Other conditions associated with GHPs include autoimmune gastritis, bile reflux, and post-gastrectomy status. GHPs are understood as a hyper-regenerative, hyper-proliferative repair response to an underlying mucosal injury. GHPs carry a risk of intraepithelial dysplasia and cancer, which is most strongly related to polyp size and age.Citation42,Citation43 Rates of dysplasia in removed GHPs range from 0.4% to 10%, and gastric adenocarcinoma is found less frequent (<1%).Citation12,Citation44 GHPs greater than 5 mm should be removed, and oncologic post-polypectomy surveillance is guided by findings on histopathological examination of the polyp and the stage of the surrounding chronic gastritis stage. GHPs result from excessive proliferation of foveolar cells and are histopathologically characterized by surface pits connected to deeper portions of glands in a linear trajectory, which can take on a serrated or star-like appearance on cross-sections.Citation12,Citation45 In addition, GHPs not infrequently have infiltration of the stroma by a variable mononucleolar cell infiltrate. The antral involvement, presentation as solitary or multifocal lesions, and the unique histopathological characteristics of foveolar cell hyperplasia with cystic dilatations, smooth muscle strands extending from muscularis mucosa towards surface, and a variable acute and chronic inflammatory stromal infiltrate are key differences to FGPs occurring in GAPPS.

Genetics

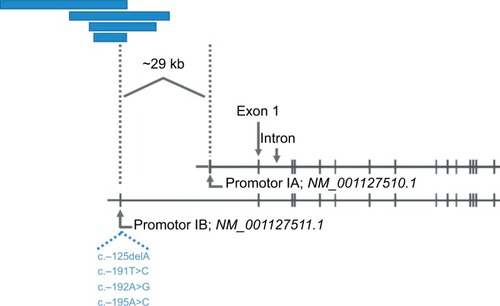

The underlying genetic aberration of GAPPS was recently discovered by Investigators from the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Adelaide, Australia.Citation46 This advancement already had significant implications both for an improved understanding of the molecular perturbations present in GAPPS and for clinical management with regard to the screening of family members at risk for GAPPS. Initial whole exome and whole genome analyses of affected family members in the first two families described in the original study in 2012 failed to produce a variant, which co-segregated with afflicted family members by GAPPS.Citation46 A loss of heterozygosity analysis in FGPs on a 46 Mb region of chromosome 5 previously identified by linkage analysis narrowed the region to 12.7 Mb, which was consequently subject to Sanger sequencing. Sequencing identified variants c.-195A>C and c.-125delA in the IB promotor of the APC gene, which completely co-segregated with the multiple affected family members in the large Australian family.Citation46 APC promotor IB variant c.-191T>C co-segregated in affected family members of families 2, 4, 5, and 6, and promotor variant c.-192A>C co-segregated in family 3 with the GAPPS phenotype. These hotspot APC promotor IB variants were consequently identified in other GAPPS families reported on more recently.Citation47–Citation49 Molecularly, the identified point mutations in the APC IB promotor significantly reduce the binding of the transcription factor Yin Yang 1 (YY1) in gastric and colon cancer cells providing functional validation of the identified germline mutation.Citation46 Importantly, methylation studies on both uninvolved stomach mucosa and FGPs in GAPPS specimens showed methylation of the promotor IA isoform of the APC gene, which the authors discussed as a possible cause for the selective gastric phenotype of the syndrome compared to the other APC-associated disorders FAP and AFAP.Citation46 It is estimated that promotor IB-driven transcription of the APC gene is ~15-fold higher than transcripts originating from the IA promotor, which is nearly universally methylated in gastric cancer and noninvolved gastric mucosa.Citation50,Citation51 Thus, reduced promotor IB activity due to the loss of the enhancer function of the transcriptional enhancer YY1 leads to a selective tumor suppressive phenotype in the stomach, which does not occur in the colon where intact promotor IA-driven APC gene transcription is preserved and able to compensate for the lost promotor IB function explaining why APC promotor IB point mutations are not associated with a colonic phenotype typically found in FAP or AFAP. Structural variants differently affecting APC promotor IA and IB function hence may form the basis for important unique phenotypic traits in APC-associated disorders adding to the many described genotype–phenotype associations described for FAP. illustrates the position of promotor IA and IB on the APC gene locus, which arê29 kb apart, in relation to several large genomic deletions described in FAP families. FAP families with underlying noncoding deletions in the APC gene promotor regions more commonly affect the IB isoform and have been reported to have a greater variability of upper GI manifestations, possibly including a higher prevalence of FGPs, compared to the FAP families with the common exomic APC mutations.Citation52 It is thought that interference with predominantly promotor IB regulated enhancer elements and thus IB activity in APC-mutation carriers with large genomic deletions manifests with different upper GI phenotypes including a greater prevalence of FGPs.Citation52,Citation53 These promotor IB structural variants, either in the form of select point mutations in the YY1 binding motif in GAPPS or large deletions affecting regulatory elements of promotor IB, have a unique gastric phenotype due to methylation of the IA promotor in the upper GI tract but preserved promotor IA function in the colon.Citation51 APC gene perturbations due to variants in the codon regions or rare structural variants affecting the IA promotor in contrast present with the classic FAP and AFAP phenotypes with the classic colonic polyposis and extracolonic manifestations.Citation54 That APC promotor IB variants are part of a greater spectrum of APC-associated disorders and are related to FAP and AFAP with its classical colonic polyposis phenotype is supported by the presence of a mild colonic phenotype in the form of a greater frequency of colonic polyps or a prior report of a point mutation in the APC IB promotor in a FAP family with colonic phenotype.Citation55,Citation56 It is tempting to speculate that the colonic phenotype in this family was due to promotor IA function not completely compensating for the loss of the impaired IB promotor.

Figure 4 Selective loss of APC gene promotor IB function by large genomic deletions or point mutations.

There are several phenotypic variabilities in GAPPS, most notably age of onset, penetrance, or degree of dysplasia to name the clinically most relevant ones. The recent genetic and molecular pathological findings may now provide some explanation for the observed heterogeneity in the clinical phenotype and manifestations of GAPPS. For example, the synchronous promotor IB variants c.-125delA and c.-195A>C found in the original large Australian family had a greater impact on APC IB promotor activity in gastric and colonic cancer cells than the c.-191T>C variant.Citation46 In addition, a number of second hits have been identified in GAPPS specimens, which might differently augment the impact of APC gene germline haploinsufficiency. Reported second hit events in GAPPS in the form of somatic mutations in FGPs or gastric adenocarcinoma of individuals affected by GAPPS include truncating APC mutations, or mutations in TP53, GNAS, or FBXW7.Citation46,Citation49,Citation55 It is tempting to speculate that the presence and type of these second hit events might be responsible for different rates of malignant transformation possibly manifesting in the accelerated development of high-grade FGP dysplasia, the development of adenomatous changes, and the clinical expression of the syndrome in general.

Clinical course

There currently is a large void in the understanding of the natural history of GAPPS, and at least two disconcerting reports have emerged, which in general, do not support prolonged endoscopic surveillance in family members with gastric polyposis due to GAPPS. Most recently, Repak et al described as a part of their European family a 54-year-old index proband with GAPPS who was diagnosed after a 19-month of endoscopic surveillance with liver metastasis and who died shortly thereafter.Citation47 Of note, there was no change in the endoscopic appearance or the histopathology of the proband’s gastric polyposis. Similarly, one of the daughters of the proband after being surveilled for 5 years showed an increase in the size of FGPs with low-grade dysplasia and focal high-grade dysplasia on repeat endoscopy.Citation47 While awaiting total gastrectomy, the patient was diagnosed with widespread metastatic disease and succumbed thereafter. Both her sisters when undergoing gastrectomy after a variable period of surveillance were found to harbor invasive stage I gastric adenocarcinoma showing again FGPs with low-grade and focal high-grade dysplasia on their last endoscopy. Worthley et al described a 33- and 48-year-old relative of the initial proband in their large Australian GAPPS family who died from metastatic intestinal-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach after being diagnosed with GAPPS previously and undergone a period of prior endoscopic observation.Citation1 In the case of the 33-year-old index patient, both adenomatous polyps and polyps with mixed FGP and adenomatous histopathology were found at total gastrectomy 2 years after the initial diagnosis. While histopathological findings as known to-date indicate a dysplasia–adenoma–carcinoma sequence in the syndrome, these reports suggest that reliance on unchanged endoscopic appearance and histopathology of sampled polyps carries the risk to miss occult sites of malignant transformation and focal progression. The inability to adequately sample the upper four-fifth of the stomach covered by hundreds of polyps by endoscopy, which are frequently large, and harbor a heterogeneous pattern of dysplasia and adenomatous changes should trigger an expedited referral to a clinical geneticist and surgical oncologist. Total gastrectomy should be considered in all GAPPS patients with fundal gland polyposis and the presence of dysplasia on gastric biopsy or polypectomy specimens, who are able to undergo major surgery. Heterogeneity in the impact of the individual primary promotor variants (c.-125 delA c.-195A>C vs c.-191T>C) differently affecting the recruitment of YY1, differences in the frequency and type of second hit events, and any underlying perturbations of the APC promotor IA are likely drivers of the malignant phenotype including rate of progression toward invasion and metastasis. As their impact on malignant transformation and cancer progression is currently unknown, the interindividual heterogeneity within GAPPS will require an individual approach to family members at risk and affected by the phenotype.

The other area of uncertainty is the incomplete understanding of other organs at risk for cancer. lists previously described GAPPS families with the age of youngest affected family member by gastric polyposis and gastric adenocarcinoma. With regard to extra gastric manifestations of GAPPS, colonic involvement in GAPPS has undergone additional investigation. McDuffie et al reported an increased incidence of colonic polyps in afflicted family members, and there is agreement on the need of colonoscopic screening with regular follow-up colonoscopic examinations guided by the initial findings in these patients.Citation1,Citation55 It is thought that the mild colonic phenotype generally with small, <20 in number hyperplastic polyps or small adenomas in GAPPS family members is due to an incomplete protection of APC promotor IA activity.Citation46 In contrast, it is interesting to note that colon cancer has been described in almost half of the GAPPS families reported to-date where family history information was available (including families with reported but not confirmed colon cancer incidences). While consistent with the phenotype of other APC-associated disorders, further follow-up of current GAPPS families and the identification of new families have to be awaited prior to including adenocarcinoma of the colon into the cancer phenotype of GAPPS. Pathological examination of colonic polyps from patients with GAPPS did not reveal any unique features, and there has been no detailed pathological review of colon cancers arising within the context of GAPPS.Citation55

Table 4 Clinicopathological characteristics of previously reported families with GAPPS

Conclusion

GAPPS is a novel, autosomal dominant gastric polyposis syndrome with a significant predisposition for adenocarcinoma of the stomach, metastasis, and death. With the recent identification of APC gene promotor IB variants as its underlying genetic aberration and a phenotypic overlap with FAP and AFAP caused by the loss of the tumor suppressor APC, GAPPS has been included as the most recent addition into APC-associated disorders. Diagnosis is made by the presence of FGPs sparing the antrum and lesser curvature of the stomach, the absence of colonic and duodenal polyposis, an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and the exclusion of other gastric polyposis syndromes and chronic use of PPIs. Family members at risk should be screened by germline mutation testing for the presence of APC promotor IB variants to initiate timely endoscopic evaluation and surveillance. GAPPS has a to-date poorly defined natural history and the rate of malignant transformation, and endoscopic surveillance in family members with gastric polyposis with high-grade dysplasia on biopsy and polypectomy specimens can miss invasive cancer. Colonoscopic surveillance is prudent while risk estimates of colon and other cancer phenotypes possibly associated with GAPPS are awaiting larger sample numbers. The creation of family registries and the formation of updated guidelines by expert consensus panels similar to the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium for the screening and management of HDGC, together with enhanced education, are likely to reduce mortality in the future.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WorthleyDLPhillipsKDWayteNGastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): a new autosomal dominant syndromeGut201261577477921813476

- Yanaru-FujisawaRNakamuraSMoriyamaTFamilial fundic gland polyposis with gastric cancerGut20126171103110422027476

- SlavinTNeuhausenSLRybakCGenetic gastric cancer susceptibility in the international clinical cancer genomics community research networkCancer Genet2017216217111119

- HampelHBennettRLBuchananAA practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessmentGenet Med2015171708725394175

- LuKHWoodMEDanielsMAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology Expert Statement: collection and use of a cancer family history for oncology providersJ Clin Oncol201432883384024493721

- RobsonMEStormCDWeitzelJWollinsDSOffitKAmerican Society of Clinical OncologyAmerican society of clinical oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibilityJ Clin Oncol201028589390120065170

- StoffelEMManguPBGruberSBHereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement of the familial risk-colorectal cancer: european society for medical oncology clinical practice guidelinesJ Clin Oncol201533220921725452455

- Lam-HimlinDParkJYCornishTCShiCMontgomeryEMorphologic characterization of syndromic gastric polypsAm J Surg Pathol201034111166219898226

- VyasMYangXZhangXGastric hamartomatous polyps-review and updateClin Med Insights Gastroenterol2016931027081323

- ArnasonTLiangWYAlfaroEMorphology and natural history of familial adenomatous polyposis-associated dysplastic fundic gland polypsHistopathology201465335336224548295

- WoodLDSalariaSNCruiseMWGiardielloFMMontgomeryEAUpper GI tract lesions in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): enrichment of pyloric gland adenomas and other gastric and duodenal neoplasmsAm J Surg Pathol201438338939324525509

- MarkowskiARMarkowskaAGuzinska-UstymowiczKPathophysiological and clinical aspects of gastric hyperplastic polypsWorld J Gastroenterol201622408883889127833379

- BeggsADLatchfordARVasenHFPeutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for managementGut201059797598620581245

- WatanabeCKomotoSTomitaKEndoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide surveyJ Gastroenterol201651432733626216651

- SlavikTMontgomeryEACronkhite–Canada syndrome six decades on: the many faces of an enigmatic diseaseJ Clin Pathol2014671089189725004941

- SweetserSAhlquistDAOsbornNKClinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunityDig Dis Sci201257249650221881972

- BurtRWGastric fundic gland polypsGastroenterology200312551462146914598262

- FreemanHJProton pump inhibitors and an emerging epidemic of gastric fundic gland polyposisWorld J Gastroenterol20081491318132018322941

- MalfertheinerPKandulskiAVeneritoMProton-pump inhibitors: understanding the complications and risksNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol2017141269771028930292

- HuangCZLaiRXMaiLZhouHLChenHJGuoHXRelative risk factors associated with the development of fundic gland polypsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201426111217122125187299

- Tran-DuyASpaetgensBHoesAWde WitNJStehouwerCDUse of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risks of Fundic Gland Polyps and Gastric Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-analysisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20161412e170517061719

- NakamuraSMatsumotoTKoboriYIidaMImpact of Helicobacter pylori infection and mucosal atrophy on gastric lesions in patients with familial adenomatous polyposisGut200251448548912235068

- StraubSFDrageMGGonzalezRSComparison of dysplastic fundic gland polyps in patients with and without familial adenomatous polyposisHistopathology20187271172117929436014

- WatanabeNSenoHNakajimaTRegression of fundic gland polyps following acquisition of Helicobacter pyloriGut200251574274512377817

- AbrahamSCNobukawaBGiardielloFMHamiltonSRWuTTTtWSporadic fundic gland polyps: common gastric polyps arising through activating mutations in the beta-catenin geneAm J Pathol200115831005101011238048

- TorbensonMLeeJHCruz-CorreaMSporadic fundic gland polyposis: a clinical, histological, and molecular analysisMod Pathol200215771872312118109

- GentaRMSchulerCMRobiouCILashRHNo association between gastric fundic gland polyps and gastrointestinal neoplasia in a study of over 100,000 patientsClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20097884985419465154

- LevyMDBhattacharyaBSporadic fundic gland polyps with low-grade dysplasia: a large case series evaluating pathologic and immunohistochemical findings and clinical behaviorAm J Clin Pathol2015144459260026386080

- KishikawaHKaidaSTakarabeSFundic gland polyps accurately predict a low risk of future gastric carcinogenesisClin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol201438450551224637176

- StolteMViethMEbertMPHigh-grade dysplasia in sporadic fundic gland polyps: clinically relevant or not?Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200315111153115614560146

- GrovesCLamlumHCrabtreeMMutation cluster region, association between germline and somatic mutations and genotype-phenotype correlation in upper gastrointestinal familial adenomatous polyposisAm J Pathol200216062055206112057910

- SampleDCSamadderNJPappasLMVariables affecting penetrance of gastric and duodenal phenotype in familial adenomatous polyposis patientsBMC Gastroenterol201818111530012100

- GarreanSHeringJSaiedAJaniJEspatNJGastric adenocarcinoma arising from fundic gland polyps in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis syndromeAm Surg2008741798318274437

- NgamruengphongSBoardmanLAHeighRIKrishnaMRobertsMERiegert-JohnsonDLGastric adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis are common, but subtle, and have a benign courseHered Cancer Clin Pract2014121424565534

- AbrahamSCParkSJMugarteguiLHamiltonSRWuTTTtWSporadic fundic gland polyps with epithelial dysplasia: evidence for preferential targeting for mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli geneAm J Pathol200216151735174212414520

- MankaneyGLeonePCruiseMGastric cancer in FAP: a concerning rise in incidenceFam Cancer201716337137628185118

- WaltonSJFraylingIMClarkSKLatchfordAGastric tumours in FAPFam Cancer201716336336928271232

- ParkSYRyuJKParkJHPrevalence of gastric and duodenal polyps and risk factors for duodenal neoplasm in korean patients with familial adenomatous polyposisGut Liver201151465121461071

- YamaguchiTIshidaHUenoHUpper gastrointestinal tumours in Japanese familial adenomatous polyposis patientsJpn J Clin Oncol201646431031526819281

- De BoerWBEeHKumarasingheMPNeoplastic lesions of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis syndrome (GAPPS) are gastric phenotypeAm J Surg Pathol20184211829112017

- CarmackSWGentaRMSchulerCMSaboorianMHThe current spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000 patientsAm J Gastroenterol200910461524153219491866

- ImuraJHayashiSIchikawaKMalignant transformation of hyperplastic gastric polyps: An immunohistochemical and pathological study of the changes of neoplastic phenotypeOncol Lett2014751459146324765156

- ASGE Standards of Practice CommitteeEvansJAChandrasekharaVThe role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomachGastrointest Endosc20158211825935705

- JainRChettyRGastric hyperplastic polyps: a reviewDig Dis Sci20095491839184619037727

- HanARSungCOKimKMThe clinicopathological features of gastric hyperplastic polyps with neoplastic transformations: a suggestion of indication for endoscopic polypectomyGut Liver20093427127520431760

- LiJWoodsSLHealeySPoint mutations in exon 1B of APC reveal gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach as a familial adenomatous polyposis variantAm J Hum Genet201698583084227087319

- RepakRKohoutovaDPodholaMThe first European family with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach: case report and review of the literatureGastrointest Endosc201684471872527343414

- BeerAStreubelBAsariRDejacoCOberhuberGGastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) - a rare recently described gastric polyposis syndrome - report of a caseZ Gastroenterol201755111131113429141268

- MitsuiYYokoyamaRFujimotoSFirst report of an Asian family with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) revealed with the germline mutation of the APC exon 1B promoter regionGastric Cancer20182161058106329968043

- TsuchiyaTTamuraGSatoKDistinct methylation patterns of two APC gene promoters in normal and cancerous gastric epitheliaOncogene200019323642364610951570

- HosoyaKYamashitaSAndoTNakajimaTItohFUshijimaTAdenomatous polyposis coli 1A is likely to be methylated as a passenger in human gastric carcinogenesisCancer Lett2009285218218919527921

- RohlinAEngwallYFritzellKInactivation of promoter 1B of APC causes partial gene silencing: evidence for a significant role of the promoter in regulation and causative of familial adenomatous polyposisOncogene201130504977498921643010

- SnowAKTuohyTMSargentNRSmithLJBurtRWNeklasonDWAPC promoter 1B deletion in seven American families with familial adenomatous polyposisClin Genet201588436036525243319

- JaspersonKWPatelSGAhnenDJAPC-associated polyposis conditionsAdamMPArdingerHHPagonRAGeneReviews RSeattle, WAUniversity of Washington1993

- McduffieLASabesanAAllgäeuerMβ-Catenin activation in fundic gland polyps, gastric cancer and colonic polyps in families afflicted by ‘gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach’ (GAPPS)J Clin Pathol201669982683327406052

- LagardeARouleauEFerrariAGermline APC mutation spectrum derived from 863 genomic variations identified through a 15-year medical genetics service to French patients with FAPJ Med Genet2010471072172220685668

- SyngalSBrandREChurchJMACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromesAm J Gastroenterol20151102223262 quiz 26325645574

- SampsonJRDolwaniSJonesSAutosomal recessive colorectal adenomatous polyposis due to inherited mutations of MYHLancet20033629377394112853198

- VogtSJonesNChristianDExpanded extracolonic tumor spectrum in MUTYH-associated polyposisGastroenterology200913719856e19711985

- JaspersonKWTuohyTMNeklasonDWBurtRWHereditary and familial colon cancerGastroenterology201013862044205820420945

- LubbeSJdi BernardoMCChandlerIPHoulstonRSClinical implications of the colorectal cancer risk associated with MUTYH mutationJ Clin Oncol200927243975398019620482

- HoweJRMitrosFASummersRWThe risk of gastrointestinal carcinoma in familial juvenile polyposisAnn Surg Oncol1998587517569869523

- BrosensLAvan HattemAHylindLMRisk of colorectal cancer in juvenile polyposisGut200756796596717303595

- van LierMGWagnerAMathus-VliegenEMKuipersEJSteyerbergEWvan LeerdamMEHigh cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and surveillance recommendationsAm J Gastroenterol201010561258126420051941

- SchreibmanIRBakerMAmosCMcgarrityTJThe hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a clinical and molecular reviewAm J Gastroenterol2005100247649015667510

- HealdBMesterJRybickiLOrloffMSBurkeCAEngCFrequent gastrointestinal polyps and colorectal adenocarcinomas in a prospective series of PTEN mutation carriersGastroenterology201013961927193320600018

- StanichPPOwensVLSweetserSColonic polyposis and neoplasia in cowden syndromeMayo Clin Proc201186648949221628613

- Riegert-JohnsonDLGleesonFCRobertsMCancer and lhermitteduclos disease are common in cowden syndrome patientsHered Cancer Clin Pract201081620565722

- TanMHMesterJLNgeowJRybickiLAOrloffMSEngCLifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTEN mutationsClin Cancer Res201218240040722252256

- BertarioLRussoASalaPMultiple approach to the exploration of genotype-phenotype correlations in familial adenomatous polyposisJ Clin Oncol20032191698170712721244

- BulowSDuodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposisGut200453338138614960520

- GibbonsDCSinhaAPhillipsRKClarkSKColorectal cancer: no longer the issue in familial adenomatous polyposis?Fam Cancer2011101112021052851

- BurtRWLeppertMFSlatteryMLGenetic testing and phenotype in a large kindred with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposisGastroenterology2004127244445115300576

- KadiyskaTKTodorovTPBichevSNAPC promoter 1B deletion in familial polyposis-implications for mutation-negative familiesClin Genet201485545245723725351

- LinYLinSBaxterMDNovel APC promoter and exon 1B deletion and allelic silencing in three mutation-negative classic familial adenomatous polyposis familiesGenome Med2015714225941542