Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain that occurs with defecation or alterations in bowel habits. Further classification is based on the predominant bowel habit: constipation-predominant IBS, diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), or mixed IBS. The pathogenesis of IBS is unclear and is considered multifactorial in nature. GI dysbiosis, thought to play a role in IBS pathophysiology, has been observed in patients with IBS. Alterations in the gut microbiota are observed in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and overgrowth may occur in a subset of patients with IBS. The management of IBS includes therapies targeting the putative factors involved in the pathogenesis of the condition. However, many of these interventions (eg, eluxadoline and alosetron) require long-term, daily administration and have important safety considerations. Agents thought to modulate the gut microbiota (eg, antibiotics and probiotics) have shown potential benefits in clinical studies. However, conventional antibiotics (eg, neomycin) are associated with several adverse events and/or the risk of bacterial antibiotic resistance, and probiotics lack uniformity in composition and consistency of response in patients. Rifaximin, a nonsystemic antibiotic administered as a 2-week course of therapy, has been shown to be safe and efficacious for the treatment of IBS-D. Rifaximin exhibits a favorable benefit-to-harm ratio when compared with daily therapies for IBS-D (eg, alosetron and tricyclic antidepressants), and rifaximin was not associated with the emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance. Thus, short-course therapy with rifaximin is an appropriate treatment option for IBS-D.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by recurring abdominal pain associated with evacuation or changes in bowel habits (ie, stool form and stool frequency).Citation1 IBS is commonly subclassified based on the predominant bowel habit (ie, constipation-predominant IBS, diarrhea-predominant IBS [IBS-D], or mixed IBS [an occurrence of both constipation and diarrhea]). A common disorder, IBS is estimated to affect ~11% of adults worldwide.Citation2,Citation3 The pathogenesis of IBS is not completely understood, but is considered multifactorial, with the immune system, gut–brain axis, and gut microbiota thought to play roles.Citation4–Citation7 Indeed, increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (ie, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α) have been observed in patients with IBS compared with healthy individuals.Citation5 Further, interactions between the gut microbiota and central nervous system (ie, gut–brain axis) are thought to play a role in IBS pathogenesis, and the interaction is likely bidirectional. For example, psychiatric comorbidities (eg, anxiety and depression) are common in patients with IBS.Citation6 Abdominal pain, a key component of the clinical definition of IBS, is one of the most common symptoms resulting in patients with IBS seeking consultation with a health care provider.Citation8 The management of IBS is based on specific GI symptoms (eg, diarrhea and constipation) and the severity of those symptoms.Citation1 However, patients with IBS may experience variations in predominant symptoms and/or IBS subtypes during their lifetime, necessitating adjustments in management approaches.Citation9

IBS has a substantial negative effect on patients. Data suggest that patients with IBS-D experience significantly greater decreases in health-related quality of life and increased impairment of daily activities compared with healthy individuals (p<0.001 for both comparisons).Citation3 In addition, work absenteeism (ie, the percentage of work time missed related to health issues) and presenteeism (ie, the percentage of impairment experienced during work time related to health issues) are significantly more common in patients with IBS-D than in healthy individuals (absenteeism, 5.1% vs 2.9%, respectively; p=0.004; presenteeism, 17.9% vs 11.3%; p<0.001).Citation3

The aim of the current article was to provide an overview of the role of short-course therapy with rifaximin in the management of patients with IBS-D.

Materials and methods

A PubMed search of English language articles available through May 9, 2017, was conducted using the following keywords to identify relevant articles and studies performed in adult humans: “irritable bowel syndrome,” “pathogenesis OR pathophysiology,” “gut dysbiosis OR microbiota,” “small intestinal bacterial overgrowth,” “breath testing,” “treatment,” “management,” “antibiotic,” and “rifaximin.”

Role of gut microbiota in IBS

Intestinal dysbiosis, or alterations in the quantity or composition of GI-associated microbiota, has been observed in patients with IBS.Citation10–Citation14 For example, results of a meta-analysis demonstrated that the expression of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium differed significantly between patients with IBS-D and healthy individuals (p=0.02 and p=0.001, respectively).Citation7 In addition, patients with IBS-D appear to have significantly lower concentrations of aerobic bacteria than that of healthy individuals (1.4×107 vs 8.4×108 colony-forming units [CFUs]/g feces, respectively; p=0.002).Citation10

In a longitudinal study, gut microbial instability (ie, differences in microbial numbers or composition; determined using culture-independent molecular analysis [ie, PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis]) was greater in patients with IBS than in healthy individuals during a 6-month period (43% vs 29%, respectively).Citation15 This greater instability (ie, temporal changes) in the gut microbial composition versus healthy individuals has also been specifically shown in patients with IBS-D.Citation13,Citation16,Citation17 In addition, when the gut microbiota of a pooled IBS subtype population was analyzed by IBS symptom severity, patients with severe IBS (defined as IBS severity score >300, maximum score of 500) had decreased microbial diversity, increased Bacteroides, and a lack of Methanobacteriales compared with the gut microbiota of healthy individuals.Citation18 To date, studies comparing the gut microbiota of patients with IBS with that of healthy individuals have been limited to demonstrating an association between dysbiosis and IBS; cause and effect remain to be elucidated.Citation19

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), characterized by quantitative and qualitative alterations in bacteria in the small intestine, is a diagnosis that may be considered in patients with nonspecific symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea.Citation20,Citation21 Further, patients who use proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be at a greater risk of developing SIBO, as findings of a meta-analysis of 19 studies reported that PPIs significantly increased the risk of SIBO (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–2.4).Citation22 However, a study of patients undergoing upper GI tract endoscopy (n=897) showed no association between PPI use and SIBO.Citation23 In 2017, the North American Consensus group on hydrogen- and methane-based breath testing proposed a bacterial concentration of >103 CFU/mL following aspiration of small intestine fluid and subsequent culture as meeting the threshold for a diagnosis of SIBO.Citation24 In one study, more patients with IBS (43%) achieved a positive culture threshold of ≥5×103 CFU/mL compared with healthy individuals (12%; p=0.002).Citation25 Conversely, a retrospective study of patients with IBS failed to show an association between IBS and SIBO (OR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1–0.7).Citation26 However, obtaining small intestinal aspirate samples for culture is an invasive procedure, and differences in findings may be related to inconsistencies in sample collection, in vitro growth, and the potential for contamination (ie, bacteria from outside the small intestine).Citation24,Citation27

Although criteria for diagnosing IBS are based on patient symptoms, breath testing – a method that measures the production of gases (eg, hydrogen and methane) that result from bacterial fermentation of orally administered but unabsorbed carbohydrates (eg, glucose, lactose, and lactulose) in the GI tract – may be used for various reasons, such as to determine the presence of SIBO or carbohydrate malabsorption.Citation1,Citation24,Citation28 A meta-analysis of 11 studies found that positive breath tests occurred more frequently in patients with IBS (n=1076) than in healthy individuals (n=509; OR, 4.5; 95% CI, 1.7–11.8; p=0.003).Citation29 A study published after that meta-analysis was conducted reported that 23.7% of patients with IBS had positive breath test results compared with 2.7% of healthy individuals (p=0.008).Citation30 That study also reported that, based on breath test results, SIBO was more prevalent in patients with IBS-D (37.0%) than in patients with other IBS subtypes (12.5%; p=0.02).Citation30 However, other studies have failed to demonstrate an association between SIBO (based on breath testing) and IBS.Citation31,Citation32 Thus, bacterial culture and breath-testing data appear to suggest that at least a subset of patients with IBS may have alterations in their gut microbiota. These findings, which remain to be confirmed by larger, well-designed studies, suggest that empiric treatment of patients with IBS thought to have comorbid SIBO may be warranted.Citation9,Citation29,Citation33

Given the multifactorial nature of IBS, various types of therapeutic options are prescribed to help manage the symptoms of IBS-D ().Citation1 To manage individual symptoms of IBS, most of these agents must be administered daily, either long term or as needed (eg, antispasmodics or peppermint oil for abdominal pain), or administered off-label to manage global IBS symptoms alongside psychiatric comorbidities (eg, tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may improve coexisting anxiety or depression, as well as decrease visceral pain).Citation9

Table 1 Therapies for the management of patients with IBS-D

Some agents (eg, antibiotics and probiotics) administered for the treatment of IBS are thought to modulate the gut microbiota, possibly by correcting dysbiosis.Citation1,Citation12–Citation14 Patients with IBS treated with short-course conventional (traditional) antibiotics (ie, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, neomycin, and metronidazole) have had improvements in IBS symptoms, such as diarrhea (p<0.05) and abdominal pain (p<0.001).Citation34 Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study demonstrated that patients with IBS receiving neomycin had a significantly greater decrease in the IBS composite symptom score (ie, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation) compared with placebo (35.0% vs 11.4%, respectively; p<0.05); neomycin was more likely to result in a clinical response (ie, ≥50% improvement from baseline in composite symptom score) than placebo (44% vs 23%; OR, 4.3; CI, 1.0–6.3; p<0.05).Citation35 Further, a retrospective chart review of patients with IBS and the presence of methane by lactulose breath testing showed that neomycin was associated with clinical response in 63% of 8 patients.Citation36 However, the use of these conventional antibiotics is limited by the risk for Clostridium difficile infection, the potential for the emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance, and the risk of systemic adverse events (AEs) such as ototoxicity (ie, neomycin).Citation37–Citation39 These agents should be avoided in routine clinical practice for the treatment of IBS. Further, some patients with IBS may not respond to retreatment with conventional antibiotics when IBS symptoms recur.Citation38,Citation40

In general, probiotics, typically administered daily, may improve global symptoms of IBS, along with bloating and flatulence.Citation9 Interestingly, data for a subset of studies in a 2016 meta-analysis (13 trials; n=889 patients) indicated that probiotics do not improve abdominal pain, a key individual symptom in IBS, versus placebo.Citation41 Furthermore, there is a lack of consistency of response in patients (),Citation41–Citation46 likely because probiotic formulations vary in composition (single or multiple species and strains of microbes) and dose and duration and also because the trials conducted have often been considered substandard.Citation9,Citation41 Moreover, results with one strain cannot be extrapolated to another strain from the same species.Citation9 However, an open-label, prospective study published in 2018 demonstrated that 30-day treatment with a commercially available probiotic significantly improved bowel function satisfaction in patients with IBS-D (n=11) compared with patients with non-IBS-D (n=15) on days 30 and 60 (p=0.05 and 0.04, respectively).Citation47 Further, following 30-day probiotic treatment, patients with IBS and concomitant SIBO experienced a significantly greater decrease from baseline in the severity of IBS symptoms compared with patients with IBS without SIBO at day 60 (71.3% vs 10.6%, respectively; p=0.02).Citation47 Given the potential benefit in targeting the gut microbiota, a nonsystemic antibiotic has been investigated to prevent the need for long-term daily therapy and minimize possible AEs.

Table 2 Summary of meta-analyses of randomized, controlled studies of antibiotics and probiotics in patients with IBS

Rifaximin for the treatment of IBS

Rifaximin, a nonsystemic antibiotic indicated in the USA for the treatment of adults with IBS-D, is administered as a 2-week course of therapy.Citation48 Rifaximin is also indicated as a daily therapy for the reduction of risk of overt hepatic encephalopathy in adults.Citation48 The mechanism of action of rifaximin, including in IBS, is not fully understood. However, its activities for the treatment of various GI-related conditions are thought to involve modulation of the gut microbiota (eg, SIBO eradication),Citation49 immune components (eg, decreased proinflammatory cytokine concentrations),Citation50 and the gut–brain axis (eg, cognitive improvement observed in patients with cirrhosis).Citation51 Rifaximin has been evaluated in three phase III IBS trials,Citation52,Citation53 and findings of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of rifaximin have been summarized in several meta-analyses ().Citation42,Citation43 In two phase III, identically designed, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, significantly more patients receiving rifaximin 550 mg three times daily (tid) for 2 weeks achieved adequate relief from global IBS symptoms for ≥2 of the first 4 weeks posttreatment compared with placebo (pooled, 40.7% vs 31.7%, respectively; p<0.001).Citation52 The durability of response to rifaximin was maintained for at least 3 months posttreatment and differed significantly from placebo (p<0.001).Citation52 Rifaximin had a safety and tolerability profile comparable with that of placebo, with headache (6.1% vs 6.6%), upper respiratory tract infection (5.6% vs 6.2%), and abdominal pain (4.6% vs 5.5%) being the most commonly reported AEs.Citation52 In addition, no patients reported C. difficile-associated diarrhea or ischemic colitis during these two trials.Citation52

In an earlier randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, investigator-initiated study that evaluated rifaximin 400 mg tid for 10 days in patients with IBS (a lower dose of rifaximin given for a shorter duration than the indicated dosing), rifaximin significantly improved global symptoms from baseline compared with placebo after 10 weeks of treatment-free follow-up (36.4% vs 21.0%, respectively; p=0.02).Citation54 Based on the two phase III trials,Citation52 the investigator-initiated trial,Citation54 and two additional trials (one phase IICitation55 and one single-centerCitation56), the 2014 American College of Gastroenterology concluded that rifaximin was effective for the reduction of total symptoms of IBS and bloating in patients with IBS-D.Citation9 In that same year, the American Gastroenterological Association provided a conditional recommendation for rifaximin for the treatment of IBS-D.Citation57

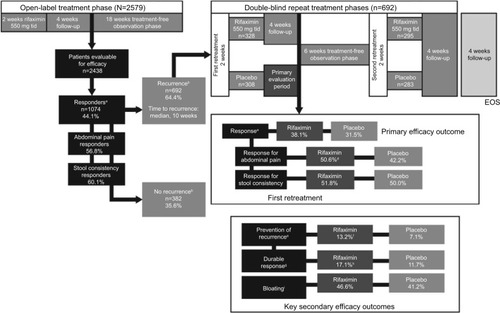

The efficacy findings of the two pivotal studiesCitation52 of rifaximin were comparable with the data reported during a phase III repeat treatment study published in 2016.Citation53 In that randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled repeat treatment trial, patients with IBS-D who responded to a 2-week course of open-label rifaximin (≥30% decrease from baseline in mean weekly pain score and ≥50% decrease from baseline in the frequency of mushy/watery stools during ≥2 of the first 4 weeks posttreatment) and experienced symptom recurrence (<30% decrease in weekly mean abdominal pain score or <50% decrease from baseline in the frequency of mushy/watery stools) for ≥3 weeks during a rolling 4-week consecutive period of the 18-week treatment-free observation phase were eligible for repeat treatment ().Citation53 Patients were randomly assigned to receive two repeat courses of rifaximin 550 mg or placebo tid for 14 days; the two double-blind courses were separated by 10 weeks.Citation53 In the open-label treatment-free observation phase, 35.6% of 1074 patients with IBS-D who responded to a 2-week course of rifaximin reported no recurrence of symptoms (ie, up to 22 weeks posttreatment) and were not further evaluated.Citation53 A significantly greater percentage of patients with recurrence who received the first repeat treatment course in the double-blind phase achieved the primary efficacy outcome of combined weekly response for abdominal pain and stool consistency during ≥2 of the first 4 weeks after repeat treatment versus placebo (38.1% vs 31.5%, respectively; p=0.03).Citation53 Interestingly, patients who entered the double-blind repeat treatment phase (ie, after responding to a 2-week course of open-label rifaximin and subsequently experiencing recurrence) had significantly lower severity in individual symptom scores at double-blind baseline (prior to starting double-blind treatment) than what had been reported at the start of open-label treatment (p<0.001, for all comparisons), suggesting residual benefit from the first course of rifaximin therapy.Citation53

Figure 1 Repeat treatment trial study design and efficacy outcomes.Citation53

Abbreviations: EOS, end of study; tid, three times daily.

Rifaximin has been available for the last 30 years (in Italy since 1987 and in the USA since 2004), is currently marketed in more than 47 countries, and has a well-established safety and tolerability profile.Citation58–Citation60 A pooled safety analysis that included data from three randomized controlled studies (ie, one phase IIb and two phase III studies) of rifaximin for the treatment of nonconstipation IBS showed that rifaximin had a safety profile comparable with that of placebo ().Citation61 Furthermore, the repeat (up to three courses) treatment trial did not identify any new safety concerns.Citation53 One patient in the repeat treatment trial developed C. difficile colitis 37 days after receiving 2-week repeat rifaximin treatment; however, this patient, who had a history of C. difficile infection, received a 10-day course of cefdinir as a treatment for a urinary tract infection immediately preceding the development of C. difficile colitis.Citation53

Table 3 Summary of safety of rifaximin 550 mg with nonconstipation IBSTable Footnotea

In a separate analysis, rifaximin was determined to be a safe and well-tolerated treatment for patients with IBS-D, with a favorable “benefit-to-harm” ratio, particularly in comparison with therapies that are administered daily, long term for IBS (eg, alosetron and tricyclic antidepressants; ).Citation62,Citation63 Although rifaximin is administered as a 2-week course of therapy in IBS-D, rifaximin has a well-established safety and tolerability profile as daily, long-term administration of 550 mg bid for the maintenance of remission of overt hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis (ie, ≥2 years; 510.5 person-years of exposure).Citation64

Table 4 Benefit to harm evaluation of treatment for patients with IBS-DTable Footnotea,Table Footnoteb

Considerations for daily, long-term versus short-course therapy

The management of IBS includes both long-term and short-term management strategies to help control symptoms. Most patients with IBS (89.6%) reported that they consider diet to cause and/or exacerbate GI symptoms, and most (91.9%) reported modifying their diet to try and decrease symptoms of IBS.Citation65 However, some specialized diets (eg, low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols [FODMAP] and low gluten/gluten-free) may be difficult for patients to maintain long term.Citation9 Specific diets, including ones low in FODMAPs, are efficacious in improving symptoms of IBS; however, patients are advised to methodically and systematically reintroduce components of the previously restricted high FODMAP diet to determine the level of food restriction that is needed to maintain symptom control.Citation66

A retrospective database analysis of any prescription type reported for patients receiving services from a large US-managed care organization (398,025 patients; 569,095 prescriptions) indicated that the predicted probability of nonadherence to treatment was greater for chronic (ongoing; long-term) versus short-course (ie, acute) therapy (34% vs 17%, respectively).Citation67 Further, questionnaire data from patients with GI disorders, including IBS, indicated that self-reported adherence to treatment was inversely correlated to patient concerns regarding harm associated with treatment (r=−0.24; p<0.001).Citation68 Adherence to treatment is important, given that many of the options available for patients with IBS-D () are ongoing, long-term (chronically administered) therapiesCitation1 and may also be associated with less desirable attributes and adverse effects.Citation69

The benefit-to-risk profile of pharmacologic therapies for patients with IBS is an important consideration in guiding therapy. Certain pharmacologic agents (eg, eluxadoline and alosetron) used in the long term and indicated for the treatment of patients with IBS-D require daily administration.Citation70,Citation71 Eluxadoline treatment effects begin to diminish within 2–3 weeks after drug discontinuation.Citation72,Citation73 Alosetron treatment effects diminish rapidly (within 1 week to 1 month) after drug discontinuation.Citation74–Citation76 Further, eluxadoline and alosetron have been associated with the occurrence of infrequent but serious AEs.Citation71,Citation73,Citation77 It is important to note that, in response to safety concerns, such as the potential for the occurrence of the rare but serious AEs of ischemic colitis and constipation complications, alosetron is available in the USA under a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program. However, an examination of 9 years of postmarketing data collected after inception of the risk management program showed that the incidence of ischemic colitis remained infrequent and stable, while complications of constipation decreased.Citation77

In March 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a safety communication warning that eluxadoline should not be administered to patients without a gallbladder because of the risk of developing serious pancreatitis that could result in hospitalization or mortality.Citation78 From May 2015 through February 2017, the agency received 120 reports of serious cases of pancreatitis or mortality. Among the 68 patients with available gallbladder status, 56 did not have a gallbladder and received the indicated dosage of eluxadoline;Citation78 hence, eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients without a gallbladder.Citation70 Furthermore, the eluxadoline prescribing information warns of a risk of sphincter of Oddi spasm, resulting in pancreatitis or hepatic enzyme elevation associated with acute abdominal pain.Citation70 A 2017 pooled safety data analysis of one phase II and two phase III clinical studies reported that while uncommon, pancreatitis was the most common serious AE reported with eluxadoline; fortunately, pancreatitis resolved in all affected patients.Citation79

Daily probiotics are commonly considered for managing GI conditions, but as noted previously, the most appropriate strain(s) to be used in managing symptoms of IBS, and at which dose, are currently unknown.Citation9,Citation80 Furthermore, evidence supporting the effectiveness of probiotics for the management of IBS symptoms is less robust than that for the treatment of other GI-related conditions (eg, pouchitis).Citation81

Given the inherent disadvantages of therapies that require long-term administration, several short-course or as-needed therapies are administered for the management of IBS. Antispasmodics (eg, dicyclomine) are efficacious for short-term relief of IBS symptoms, but results of a pooled analysis of 15 clinical studies indicated an increased risk of AEs versus placebo (relative risk, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.4).Citation9 Antispasmodics may in fact be administered as a long-term therapy, but are also administered as needed to manage individual symptoms. Although data on efficacy and safety in IBS are limited, fecal microbial transplant as short-course or as-needed therapy is currently considered an investigational treatment and is a complex procedure involving a donor and a patient.Citation82

The efficacy of the nonsystemic agent rifaximin is favorable for the treatment of IBS-D compared with placebo in clinical studies,Citation52,Citation53 and the difference between the percentage of patients achieving response with rifaximin versus placebo (range, 7% to 10%) is consistent with the findings of an analysis of clinical trials for eluxadoline (range, 4% to 13%), another therapy used for the treatment of IBS-D.Citation73 In a clinical study of IBS-D treatment with alosetron, differences between three alosetron dosing regimens and placebo ranged from 12.2% to 20.1%.Citation83 Further, the placebo effect has been established in patients with IBS, as data from a randomized, controlled study of patients administered open-label placebo showed that patients achieved a significant improvement in IBS symptoms and symptom severity compared with no treatment (p=0.002 and 0.03, respectively).Citation84 The mechanism behind the placebo effect in IBS remains to be elucidated but may involve neurological and psychological aspects, including patient expectations for symptom relief and conditioning, based on previous experiences with therapy, as well as the gut–brain axis.Citation6,Citation85

Rifaximin exhibits a favorable benefit-to-risk profile and is also administered as a short-course therapy for IBS-D. Given the well-known safety concerns regarding the effects of systemic antibiotics on the gut microbiota, health care providers may be concerned about the potential negative effect of nonsystemic rifaximin on the gut microbiota of patients with IBS-D. However, along with its favorable safety and tolerability profile, rifaximin has no apparent detrimental effects on gut microbiota and has not been associated with the emergence of clinically relevant bacterial antibiotic resistance in preclinical and clinical studies.Citation86–Citation89 Treatment with rifaximin 550 mg tid for 2 weeks did not alter the overall composition of the gut microbiota in patients with nonconstipation IBS 4 weeks after the treatment ended.Citation87 Further, repeat rifaximin treatment did not alter the composition of the gut microbiota in patients with IBS-D.Citation87 Greater diversity in the gut microbiota was observed in patients with nonconstipation IBS after treatment with rifaximin, which steadily increased for up to 6 weeks after treatment; however, the increase from baseline in gut microbiota diversity did not achieve the level observed in the samples obtained from healthy individuals.Citation87 Similarly, patients with IBS-D receiving up to three 2-week courses of treatment with rifaximin in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial experienced modest, transient changes in the relative abundance of multiple taxa of the fecal microbiota, including Peptostreptococcaceae and Clostridiaceae.Citation90 Observed changes were generally reversed by the end of the study (46 weeks).Citation90 Gut microbiota changes that are most relevant to explaining the clinical effectiveness of rifaximin in improving symptoms of IBS-D may be too subtle for current DNA-based methods or analytics to detect. The resistance of staphylococcal isolates to rifampicin was not observed after a 10-day course with rifaximin in rats;Citation86 similarly, in patients with IBS-D receiving up to three courses of a 2-week treatment with rifaximin in the repeat treatment study, skin swabs from multiple locations and stool samples showed no evidence of resistance of staphylococcal isolates to rifaximin, rifampin, or other clinically relevant antibiotics.Citation88,Citation89

Conclusion

IBS is a chronic, common GI disorder, and both long-term and short-course therapies are considered part of an overall management strategy. Modulation of the gut microbiota with agents (eg, antibiotics and probiotics) thought to correct gut dysbiosis that occurs in patients with IBS is one approach. Data demonstrate that short-course (ie, 2-week) therapy with the nonsystemic antibiotic rifaximin is safe and efficacious for the treatment of IBS-D. Unless there is a contraindication to using a 2-week course of rifaximin, the literature suggests that it would be a reasonable first-line treatment choice for IBS-D, given the response rate and the durability of response, as well as its benefit-to-risk profile and lack of associated clinically significant bacterial antibiotic resistance.

Author contributions

Chang contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Technical editorial assistance was provided, under the direction of the author, by Mary Beth Moncrief and Sophie Bolick (Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA, USA). Funding for this study was provided by Salix Pharmaceuticals, Bridgewater, NJ, USA.

Disclosure

The author has served as an advisory board member of Salix Pharmaceuticals. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LacyBEMearinFChangLBowel disordersGastroenterology2016150613931407

- LovellRMFordACGlobal prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201210771272122426087

- BuonoJLCarsonRTFloresNMHealth-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrheaHealth Qual Life Outcomes20171513528196491

- EnckPAzizQBarbaraGIrritable bowel syndromeNat Rev Dis Primers201621601427159638

- LiebregtsTAdamBBredackCImmune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology2007132391392017383420

- KoloskiNAJonesMKalantarJWeltmanMZaguirreJTalleyNJThe brain–gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: a 12-year prospective population-based studyGut20126191284129022234979

- LiuHNWuHChenYZChenYJShenXZLiuTTAltered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysisDig Liver Dis201749433133728179092

- HunginAPChangLLockeGRDennisEHBarghoutVIrritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impactAliment Pharmacol Ther200521111365137515932367

- FordACMoayyediPLacyBEAmerican College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipationAm J Gastroenterol2014109Suppl 1S2S2625091148

- CarrollIMChangYHParkJSartorRBRingelYLuminal and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeGut Pathog2010211921143915

- CarrollIMRingel-KulkaTKekuTOMolecular analysis of the luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol20113015G799G80721737778

- CarrollIMRingel-KulkaTSiddleJPRingelYAlterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeNeurogastroenterol Motil201224652153022339879

- DurbánAAbellánJJJiménez-HernándezNInstability of the faecal microbiota in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeFEMS Microbiol Ecol201386358158923889283

- ParkesGCRaymentNBHudspithBNDistinct microbial populations exist in the mucosa-associated microbiota of sub-groups of irritable bowel syndromeNeurogastroenterol Motil2012241313922070725

- MättoJMaunukselaLKajanderKComposition and temporal stability of gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome–a longitudinal study in IBS and control subjectsFEMS Immunol Med Microbiol200543221322215747442

- MaukonenJSatokariRMättöJSoderlundHMattila-SandholmTSaarelaMPrevalence and temporal stability of selected clostridial groups in irritable bowel syndrome in relation to predominant faecal bacteriaJ Med Microbiol200655Pt 562563316585652

- KassinenAKrogius-KurikkaLMäkivuokkoHThe fecal micro-biota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjectsGastroenterology20071331243317631127

- TapJDerrienMTornblomHIdentification of an intestinal micro-biota signature associated with severity of irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology20171521111123.e11827725146

- ChangCLinHDysbiosis in gastrointestinal disordersBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol201630131527048892

- SachdevAHPimentelMGastrointestinal bacterial overgrowth: pathogenesis and clinical significanceTher Adv Chronic Dis20134522323123997926

- PylerisEGiamarellos-BourboulisEJTzivrasDKoussoulasVBarbatzasCPimentelMThe prevalence of overgrowth by aerobic bacteria in the small intestine by small bowel culture: relationship with irritable bowel syndromeDig Dis Sci20125751321132922262197

- SuTLaiSLeeAHeXChenSMeta-analysis: proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowthJ Gastroenterol2018531273628770351

- Giamarellos-BourboulisEJPylerisEBarbatzasCPistikiAPimentelMSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with irritable bowel syndrome and is independent of proton pump inhibitor usageBMC Gastroenterol20161616727402085

- RezaieABuresiMLemboAHydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: the North American ConsensusAm J Gastroenterol2017112577578428323273

- PosserudIStotzerPOBjörnssonESAbrahamssonHSimrénMSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndromeGut200756680280817148502

- ChoungRSLockeGR3rdEpidemiology of IBSGastroenterol Clin North Am201140111021333897

- JacobsCCoss AdameEAttaluriAValestinJRaoSSDysmotility and proton pump inhibitor use are independent risk factors for small intestinal bacterial and/or fungal overgrowthAliment Pharmacol Ther201337111103111123574267

- RanaSVMalikABreath tests and irritable bowel syndromeWorld J Gastroenterol201420247587760124976698

- ShahEDBasseriRJChongKPimentelMAbnormal breath testing in IBS: a meta-analysisDig Dis Sci20105592441244920467896

- SachdevaSRawatAKReddyRSPuriASSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in irritable bowel syndrome: frequency and predictorsJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201126Suppl 3135138

- GhoshalUCParkHGweeKABugs and irritable bowel syndrome: the good, the bad and the uglyJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201025224425120074148

- ParkJHParkDIKimHJThe relationship between small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth and intestinal permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndromeGut Liver20093317417920431742

- GhoshalUCGhoshalUSmall intestinal bacterial overgrowth and other intestinal disordersGastroenterol Clin North Am201746110312028164845

- PimentelMChowEJLinHCEradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol200095123503350611151884

- PimentelMChowEJLinHCNormalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studyAm J Gastroen-terol2003982412419

- LowKHwangLHuaJZhuAMoralesWPimentelMA combination of rifaximin and neomycin is most effective in treating irritable bowel syndrome patients with methane on lactulose breath testJ Clin Gastroenterol201044854755019996983

- BlondeauJMWhat have we learned about antimicrobial use and the risks for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea?J Antimicrob Chemother200963223824219028718

- BasseriRJWeitsmanSBarlowGMPimentelMAntibiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterol Hepatol (N Y)20117745549322298980

- WardKMRounthwaiteFJNeomycin ototoxicityAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol1978872 Pt 1211215646289

- YangJLeeHRLowKChatterjeeSPimentelMRifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBSDig Dis Sci200853116917417520365

- ZhangYLiLGuoCEffects of probiotic type, dose and treatment duration on irritable bowel syndrome diagnosed by Rome III criteria: a meta-analysisBMC Gastroenterol20161616227296254

- LiJZhuWLiuWWuYWuBRifaximin for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trialsMedicine (Baltimore)2016954e253426825893

- MeneesSBManeerattannapornMKimHMCheyWDThe efficacy and safety of rifaximin for the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol20121071283522045120

- DidariTMozaffariSNikfarSAbdollahiMEffectiveness of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: updated systematic review with meta-analysisWorld J Gastroenterol201521103072308425780308

- FordACQuigleyEMLacyBEEfficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol2014109101547156125070051

- MoayyediPFordACTalleyNJThe efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic reviewGut201059332533219091823

- LeventogiannisKGkolfakisPSpithakisGEffect of a preparation of four probiotics on symptoms of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: association with intestinal bacterial overgrowthProbiotics Antimicrob Proteins Epub201835

- Xifaxan® (rifaximin) tablets, for oral use [package insert]Bridgewater, NJSalix Pharmaceuticals2018

- GattaLScarpignatoCSystematic review with meta-analysis: rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowthAliment Pharmacol Ther201745560461628078798

- KalambokisGNMouzakiARodiMRifaximin improves systemic hemodynamics and renal function in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and ascitesClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201210781581822391344

- BajajJSHeumanDMSanyalAJModulation of the metabiome by rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathyPLoS One201384e6004223565181

- PimentelMLemboACheyWDRifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipationN Engl J Med20113641223221208106

- LemboAPimentelMRaoSSRepeat treatment with rifaximin is safe and effective in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology201615161113112127528177

- PimentelMParkSMirochaJKaneSVKongYThe effect of a non-absorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2006145855756317043337

- LemboAZakkoSFFerreiraNLRifaximin for the treatment of diarrhea-associated irritable bowel syndrome: short term treatment leading to long term sustained responseGastroenterology20081344 Suppl 1A-545

- ShararaAIAounEAbdul-BakiHMounzerRSidaniSEl HajjIA randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulenceAm J Gastroenterol2006101232633316454838

- WeinbergDSSmalleyWHeidelbaughJJSultanSAmerican Gastro-enterological AssociationAmerican Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology201414751146114825224526

- KimerNKragAMøllerSBendtsenFGluudLLSystematic review with meta-analysis: the effects of rifaximin in hepatic encephalopathyAliment Pharmacol Ther201440212313224849268

- FestiDMazzellaGOrsiniMRifaximin in the treatment of chronic hepatic encephalopathy; results of a multicenter study of efficacy and safetyCurr Ther Res1993545598609

- MiglioFValpianiDRosselliniSRFerrieriARifaximin, a non-absorbable rifamycin, for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. A double-blind, randomised trialCurr Med Res Opin199713105936019327194

- SchoenfeldPPimentelMChangLSafety and tolerability of rifaximin for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome without constipation: a pooled analysis of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsAliment Pharmacol Ther201439101161116824697851

- ShahEKimSChongKLemboAPimentelMEvaluation of harm in the pharmacotherapy of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Med2012125438139322444104

- ShahEPimentelMEvaluating the functional net value of pharmacologic agents in treating irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther201439997398324612075

- MullenKDSanyalAJBassNMRifaximin is safe and well tolerated for long-term maintenance of remission from overt hepatic encephalopathyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20141281390139724365449

- HayesPCorishCO’MahonyEQuigleyEMA dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndromeJ Hum Nutr Diet201427Suppl 23647

- MuirJGGibsonPRThe low FODMAP diet for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome and other gastrointestinal disordersGastroenterol Hepatol (N Y)20139745045223935555

- ShinJMcCombsJSSanchezRJUdallMDeminskiMCCheethamTCPrimary nonadherence to medications in an integrated healthcare settingAm J Manag Care201218842643422928758

- CassellBGyawaliCPKushnirVMGottBMNixBDSayukGSBeliefs about GI medications and adherence to pharmacotherapy in functional GI disorder outpatientsAm J Gastroenterol2015110101382138725916226

- SpenceMMKarimFALeeEAHuiRLGibbsNERisk of injury in older adults using gastrointestinal antispasmodic and anticholinergic medicationsJ Am Geriatr Soc20156361197120226096393

- VIBERZI® (eluxadoline) tablets, for oral use, CIV [package insert]Irvine, CAAllergan USA, Inc2017

- Lotronex® (alosetron hydrochloride) tablets [package insert]Roswell, GASebela Pharmaceuticals Inc2016

- DoveLSLemboARandallCWEluxadoline benefits patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea in a phase 2 studyGastroenterology2013145232933823583433

- LemboAJLacyBEZuckermanMJEluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrheaN Engl J Med2016374324225326789872

- CheyWDCheyWYHeathATLong-term safety and efficacy of alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol200499112195220315555002

- LemboTWrightRABagbyBAlosetron controls bowel urgency and provides global symptom improvement in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol20019692662267011569692

- CamilleriMNorthcuttARKongSDukesGEMcSorleyDMangelAWEfficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trialLancet200035592091035104010744088

- TongKNicandroJPShringarpureRChuangEChangLA 9-year evaluation of temporal trends in alosetron postmarketing safety under the risk management programTherap Adv Gastroenterol201365344357

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA drug safety communication: FDA warns about increased risk of serious pancreatitis with irritable bowel drug Viberzi (eluxadoline) in patients without a gallbladder [Press Release]Silver Spring, MDUS Food and Drug Administration Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm546154.htm. Published March 15, 2017Accessed June 11, 2018

- CashBDLacyBESchoenfeldPSDoveLSCovingtonPSSafety of eluxadoline in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrheaAm J Gastroenterol2017112236537427922029

- WhelanKEditorial: The importance of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of probiotics and prebioticsAm J Gastroenterol2014109101563156525287086

- IslamSUClinical uses of probioticsMedicine (Baltimore)2016955e265826844491

- MalnickSMelzerEHuman microbiome: from the bathroom to the bedsideWorld J Gastrointest Pathophysiol201563798526301122

- KrauseRAmeenVGordonSHA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg and 1 mg alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBSAm J Gastroenterol200710281709171917509028

- KaptchukTJFriedlanderEKelleyJMPlacebos without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndromePLoS One2010512e1559121203519

- FinnissDGKaptchukTJMillerFBenedettiFBiological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effectsLancet2010375971568669520171404

- KimMSMoralesWHaniAAThe effect of rifaximin on gut flora and Staphylococcus resistanceDig Dis Sci20135861676168223589147

- SoldiSVasileiadisSUggeriFModulation of the gut microbiota composition by rifaximin in non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome patients: a molecular approachClin Exp Gastroenterol2015830932526673000

- DuPontHLWolfRAIsraelRJPimentelMAntimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus isolates from the skin of patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome treated with repeat courses of rifaximinAntimicrob Agents Chemother2016611pii:e02165e02116

- PimentelMCashBDLemboAWolfRAIsraelRJSchoenfeldPRepeat rifaximin for irritable bowel syndrome: no clinically significant changes in stool microbial antibiotic sensitivityDig Dis Sci20176292455246328589238

- FodorAPimentelMCheyWDRifaximin is associated with modest, transient decreases in multiple taxa in the gut microbiota of patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeGut Microbes Epub2018430