Abstract

Collagenous colitis (CC) is an increasingly recognized cause of chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by watery non-bloody diarrhea. As a lesser studied inflammatory bowel disease, many aspects of the CC’s natural history are poorly understood. This review discusses strategies to optimally manage CC. The goal of therapy is to induce clinical remission, <3 stools a day or <1 watery stool a day with subsequent improved quality of life (QOL). Antidiarrheal can be used as monotherapy or with other medications to control diarrhea. Budesonide therapy has revolutionized treatment and is superior to prednisone, however, the treatment is associated with high-relapse rates and the management of refractory disease is challenging. Ongoing trials will address the safety and efficacy of low-dose maintenance therapy. For those with refractory disease, case reports and case series support the role of biologic agents. Diversion of the fecal stream normalizes colonic mucosal changes and ileostomy may be considered where anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents are contraindicated. Underlying celiac disease, bile salt diarrhea, and associated thyroid dysfunction should be ruled out. The author recommends smoking cessation as well as avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories as well as other associated medications.

Introduction

Microscopic colitis (MC) is an increasingly recognized cause of chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by watery non-bloody diarrhea.Citation1 There are two main subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC), the hallmarks of which are a history of watery diarrhea, normal or near normal appearing colonic mucosa at endoscopy and characteristic microscopic features.Citation2

It classically occurs in elderly women. Since the first description of a case of CC over three decades ago,Citation3 MC has been associated with celiac disease and other autoimmune disordersCitation4,Citation5 as well as with the use of certain medications, particularly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).Citation6,Citation7 Unlike the other inflammatory bowel diseases, many aspects of the condition’s etiology, pathogenesis, and natural history remain poorly understood. Prior to the introduction of budesonide, the wide range of medications prescribed reflects the lack of specific guidelines for the treatment of MC. With few randomized trials available to guide management.Citation8 Treatment was based predominantly on the individual preference and experience of the treating physician, taking into account the pattern and severity of symptoms and potential contraindications to the use of specific therapies.Citation9 CC is more clearly defined than LC, furthermore, non-specific colonic lymphocyte infiltration is frequently encountered.

This review discusses strategies to optimally manage CC.

Collagenous colitis

Epidemiology

CC was first described in 1976 when a thick subepithelial collagenous deposit in the colorectal mucosa was identified in a rectal biopsy from a patient with chronic diarrhea.Citation3 It classically occurs in middle-aged females, with a peak incidence around 60–70 years of age but has been described in all age groups, including the pediatric population.Citation10,Citation11

An incidence of 5–10 per 100,000 has been described in population-based studies with a prevalence of CC in Olmsted County, MN, USA in 2010 of 90.4 per 100,000 and in Örebro, Sweden of 67.7 per 100,000.Citation12,Citation13

A recent meta-analysis of 25 studies by Tong et al reports a pooled incidence rate of 4.14 per 100,000 person years with steadily increasing incidence rates until 2000, but since then stable rates have been observed in the USA, Spain, and Sweden.Citation14 However, higher reports were reported in a 10 year Danish pathology study with annual incidence rates increasing from 2.9 to 14.9 per 10,000. This rise corresponded with an increase in biopsies taken and the authors conclude that this may represent increased diagnostic activity.Citation15

A Korean study of chronic diarrhea detected CC in 4% of patients similar to rates recorded in the western worldCitation16 and has been reported with lower prevalence rates in Indian and Malaysian studies.Citation17,Citation18

Pathophysiology

CC is a multifactorial disease, likely the result of an aberrant immune reaction to luminal antigens in predisposed individuals, with subsequent epithelial barrier dysfunction in the colonic mucosa.Citation19

An aberrant T lymphocyte response is thought to drive chronic gut inflammation and a Th1 cytokine profile predominates with elevated levels of interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β.Citation20 The mechanism of diarrhea has been attributed to reduced Na+ and Cl− absorption accompanied by active Cl− secretion. Watery stools in CC are driven by a combination of osmotic and secretory components as well as impaired barrier function.Citation21

Unlike Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis there is little data to suggest genetic inheritance, however, there are reports of familial cases of CC. Two families are described, in each two first degree relatives develop CC and in all four patients the human leukocyte A2 antigen was detected.Citation22

Variations in matrix metalloproteinase-9 and TNFα gene expression have been described.Citation23,Citation24

Others postulate that CC occurs as a sequela to infectious colitis with the reports of development after Yersinia enterocolitica and Clostridium difficile infections.Citation25,Citation26 Furthermore, resolution of symptoms following treatment for Helicobacter pylori has been reported.Citation27

The development of a thickened collagen band is attributed to abnormal collagen metabolism. Subepithelial matrix deposition is driven by increased expression of fibrogenic gene procollagen I and metalloproteinase inhibitor and promyofibroblastic cells as well as impaired fibrinolysis.Citation28,Citation29

Increased levels of eosinophils transforming growth factor beta expression have been demonstrated in patients with CC, and this is thought to drive tissue collagen accumulation.Citation30 Increased expression of nitric oxide synthase driven by upregulation of nuclear transcription factor beta results in increased colonic nitric oxide production, which in turn may cause a secretory diarrhea.Citation31

Symptoms

The hallmark of CC is chronic watery diarrhea; other symptoms include abdominal pain, urgency fecal incontinence, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss.Citation32,Citation33

CC is rarely associated with serious complications, however, cases of spontaneous and postcolonoscopy perforation have been reportedCitation34,Citation35 and Bohr et al propose a connection between mucosal tears and colonic perforation in CC.Citation34 Unlike chronic inflammation seen in ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis, no increased risk of colorectal cancer has been attributed to CC, furthermore, it may be protective against colorectal cancer. In a study of 305 patients undergoing colonoscopy for evaluation of chronic non-bloody diarrhea, 16% had MC, and patients with MC were negatively associated with the risk of neoplastic polyps.Citation36

The clinical symptoms may be misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A total of 247 who were diagnosed with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel underwent colonoscopy and 6% were subsequently diagnosed with MC (13 LC, 2 CC).Citation37 Interestingly, colonoscopies performed in patients who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for IBS were significantly more likely to find organic gastrointestinal pathology in those with diarrhea predominant symptoms, with MC diagnosed in 2.2% of patients.Citation38 Additionally, there is considerable symptomatic overlap between both disorders.Citation39,Citation40

Quality of life (QOL) was severely impaired in Swedish patients, particularly when the colitis is active compared to the background population.Citation41 A Swedish case-control study subsequently demonstrated that abdominal pain, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, fecal incontinence, and nocturnal defecation were significantly more prevalent in CC patients compared with controls.Citation42

Risk factors

Traditionally, MC was considered a condition of middle-aged women using aspirin and NSAIDs but now many classes of drugs including selective seratonin reuptake inhibitors, statins, proton pump inhibitors, topirimate, venotonic agents, and histamine antagonists have been associated with medication related colitides.Citation6,Citation32,Citation43–Citation45 This highlights the importance of taking a detailed history, as symptoms can resolve upon withdrawal of the offending agent. However, evidence supporting cause and effect is lacking, in fact, many of these medications list diarrhea as a side effect.

Smoking is consistently reported as an environmental risk factor in the development of CC.Citation46–Citation48 This may be related to impaired colonic circulatory changes. The smokers developed their disease >10 years earlier than nonsmokers, but smoking does not influence the subsequent disease course.Citation49

The author recommends obtaining a detailed medication, diet, and smoking history to identify factors that may exacerbate symptoms, furthermore, coexisting causes of diarrhea (celiac disease or bile-salt diarrhea) should be considered.

Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of MC in 222 patients was studied and a history of concomitant autoimmune disorders was recorded in 62 patients (28%). Twenty-six patients (11%) had either a known diagnosis of celiac disease or were diagnosed at the same time as their lower gastrointestinal examination.Citation9 This underlines the particular importance of colonic biopsy in patients whose celiac disease remains symptomatic despite adherence to a gluten-free diet. Recently, data from a Canadian population study report a strong association between MC and celiac disease with concomitance being ~50 times that expected in the general population.Citation50 A Spanish case-control study recently showed that autoimmune diseases were independently associated with the risk of MC development.Citation46

Diagnosis

There are no reliable biomarkers, no specific laboratory tests, stool cultures are sterile and radiological findings are normal.

Fecal lactoferrin and calprotectin, which can be used as non-invasive markers of inflammation in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are not reliable in the diagnosis or assessment of CC.Citation51

Endoscopic evaluation of the colon can be normal, however, erythema, edema, change in vascularity, mucosal tears, and nodularity have been described.Citation2,Citation52–Citation54

The diagnosis is made based on characteristic histological findings in colonic mucosal biopsies. The key histological feature of CC is a thickened collagen band under the surface epithelium.Citation55,Citation56 The European consensus guidelines on diagnosis state that the thickness of the collagen band should exceed 10 μm (normal <3 μm) in well-oriented biopsies (cut perpendicularly to the mucosal surface).Citation55 The band can appear thicker (up to 70 μm) and band thickness greater than 15mm is usually associated with diarrhea,Citation57 but there is no direct correlation between band thickness and symptoms.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining is sufficient for diagnosis in most cases. In questionable cases special collagen stains (blue trichrome, Goldner, and Sirius red) or immunohistochemistry with anti-tenascin antibodies are required for diagnosis.Citation58

Findings can be patchy in nature, with colonic segments affected to varying extents.Citation57 The subepithelial collagen band tends to be less thick in the distal colon, in particular the rectum and sigmoid colon.Citation59,Citation60 Carpenter et al demonstrated that in patients with proximal inflammation left-sided biopsies alone would have missed 40% of cases.Citation61 Therefore, rectal and left-sided biopsies alone are insufficient for diagnosis. The best approach to diagnosis is obtaining multiple biopsies throughout the colon submitted as individual pathology specimens.Citation62–Citation64

Treatment

Goals of therapy

No curative therapy currently exists for MC. The goal of therapy is to induce clinical remission, <3 stools a day or >1 watery stool a day with subsequent improved QOL. Prior to the introduction of budesonide, choice of treatment relied largely on the experience of the individual physician or institution and was based on observational data, with few randomized trials available to guide management;Citation8 the few controlled trials that exist have mainly evaluated budesonide.

Hjortswang et al studied the impact of colonic symptoms on health-related QOL in CC and based on these defined criteria for remission and disease activity.Citation65 QOL was impaired in those with a mean of ≥3 stools/day or a mean of ≥1 watery stool/day, therefore, the Hjortswang-Criteria propose that clinical remission in CC is defined as a mean of <3 stools/day and a mean of <1 watery stool per day and disease activity to be a daily mean of ≥3 stools or a mean of ≥1 watery stool ().

Table 1 Hjortswang-Criteria definition of clinical disease activity in collagenous colitis

Avoidance of environmental triggers

Smoking cessation is recommended as well as withdrawal of medications associated with CC where possible. The author recommends a detailed medication history and where possible cessation of potentially provocative agents.Citation66

Symptomatic management of diarrhea

For control of symptoms, loperamide is an effective treatment. Antidiarrheals can be used as monotherapy or with other medications to control diarrhea.Citation67,Citation68 Although these have not formally been subject to randomized placebo-controlled trials, they are considered first-line therapy in patients with mild symptoms for symptomatic response.

In patients with associated bile-acid malabsorption cholestyramine may be considered as cholestyramine may adhere to bacterial toxins that have been implicated in CC pathogenesis.

Corticosteroids

The use of prednisone in the management of CC is limited given inferior efficacy and increased side effect profile compared to budesonide.

Compared to budesonide, prednisone is associated with a lower response rate, more side effects, and a higher risk of relapse when therapy is withdrawn.

The clinical pathological effect of prednisolone was studied prospectively in six patients with CC. Prednisolone resulted in a transient decrease in stool frequency, with a trend toward decreased inflammatory changes in posttreatment biopsies but without resolution of the collagen band (except in one patient).Citation69

Gentile et al compared clinical outcomes in 80 patients with MC (40 CC, 40 LC) treated with corticosteroids.Citation70 Among samples, 17 were treated with prednisone (21.2%) and 63 with budesonide (78.8%). Significantly higher rates of clinical response were observed in the budesonide treatment group (82.5% vs 52.9%; odds ratio, 4.18; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.3–13.5) with lower rates of recurrence after treatment discontinuation. Furthermore, a randomized, double-blind trial of short-term prednisolone 50 mg or placebo demonstrated incomplete remission in nine patients.Citation71 Therefore, prednisone therapy is not recommended as a first-line treatment for CC.

Budesonide

Budesonide remains the first-line therapy, significantly improving symptoms and QOL. It is a locally active corticosteroid that undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver with subsequent low systemic exposure.

A systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials concluded that budesonide was safe, effective, and well tolerated for induction and maintenance of clinical and histological remission; evidence for bismuth, prednisone, probiotics, mesalamine, and cholestyramine was weaker.Citation72

When symptoms persist despite antidiarrheals the author suggests treatment with budesonide. A suggested approach is 9 mg daily for 6–8 weeks. If symptoms persist or recur budesonide 9 mg can be used for 12 weeks and then tapered accordingly. Budesonide short-term therapy is safe and effective and can improve QOL.Citation72–Citation75 A meta-analysis of eight randomized trials that included 248 patients randomized to budesonide or placebo demonstrated that short-term clinical response rates were significantly higher with budesonide, as compared with placebo (risk ratio [RR] 3.1; 95% CI, 2.1–4.6).Citation76

In a Phase III placebo-controlled, multicenter study, Miehlke et al studied budesonide and mesalamine as short-term therapies for CC.Citation77 In a double-blind, double-dummy manner patients with active disease were treated with 9 mg once daily budesonide (n=30), 3 g once daily mesalamine (n=25), or placebo (n=37) for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission (<3 bowel motions a day).

After 8 weeks therapy, 84.8% of patients on budesonide were in clinical remission (<3 bowel motions a day) compared to 60.6% receiving placebo, using the Hjortswang-Criteria for clinical remission 80% of patients receiving budesonide therapy entered clinical remission compared to 37.8% of patients treated with placebo (P=0.0006). Of those patients given mesalamine 44% achieved clinical remission, but superior outcomes were seen with budesonide (P=0.0035). Furthermore, budesonide therapy was shown to improve histological scores, stool consistency and abdominal pain. There were no differences in adverse effects noted between treatment groups.

Budesonide has been shown to significantly reduce the histological inflammatory changes in CC with no change in the collagen thickness band, but a significant decrease in the lamina propria infiltrate.Citation78

Using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index tool, QOL in patients with CC randomized to budesonide or placebo was assessed and found that QOL scores are low in patients with CC, after 6 weeks of treatment with budesonide scores improved significantly compared to those receiving placebo.Citation79

Recurrent symptoms and maintenance therapy

Recurrence after budesonide treatment is common and can be retreated with budesonide as intermittent therapy or as continuous maintenance therapy ideally at the lowest dose that maintains clinical remission.Citation76 However, low-dose maintenance treatment is controversial, mainly due to risk of steroid-related side effects.

Risk factors for relapse after budesonide withdrawal were assessed in 123 patients who achieved clinical remission with budesonide therapy for CC in controlled trials.Citation80 The rate of relapse was 61%. Risk factors associated with relapse included high-stool frequency at baseline and a long duration of diarrhea. Time to relapse was shorter in those with a baseline stool frequency of >5 per day and in those with a >12 month history of diarrhea. Budesonide maintenance therapy was a protective factor against recurring symptoms and maintenance therapy delayed time from relapse from 56 to 207 days.

In a randomized controlled trial assessing long-term outcomes of budesonide therapy clinical relapse occurred in 61% of patients after a median of 2 weeks and relapse occurred significantly more often in patients over the age of 60 years.Citation80

A meta-analysis on the short- and long-term efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of MC of 248 patients from eight trials randomized to corticosteroids revealed that short- and long-term treatment with budesonide is effective and well tolerated for MC and was associated with clinical and histological response.Citation76 Again, this confirmed high rates of symptom relapse (46%–80%) of patients within 6 months of treatment discontinuation.

A prospective randomized, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose budesonide (mean dose 4.5 mg a day) for the maintenance of clinical remission in CC demonstrated that budesonide maintained clinical remission for at least 1 year in 61.4% (27/44 patients) compared to 16.7% (8/48 patients) receiving placebo (treatment difference 44.5% in favor of budesonide; 95% CI [26.9%–62.7%], P<0.001).Citation81 There was a high-relapse rate after discontinuation 82.1% (23/28 patients). Overall treatment was well tolerated with no serious adverse events, and the authors conclude that treatment extension with low-dose budesonide beyond 1 year may be beneficial given the high-relapse rate after budesonide discontinuation.

Refractory CC

Ten to 20 percent of patients do not respond to budesonide therapyCitation74 and there is a paucity of data to guide therapy in those with refractory CC.

In those not responding to antidiarrheals and budesonide one should assess for other causes of chronic diarrhea, particularly celiac disease and thyroid dysfunction given the higher incidence of autoimmune diseases in the patient population. Persistent use of NSAIDS needs to be ruled out as well as IBS and bile salt diarrhea ().Citation32

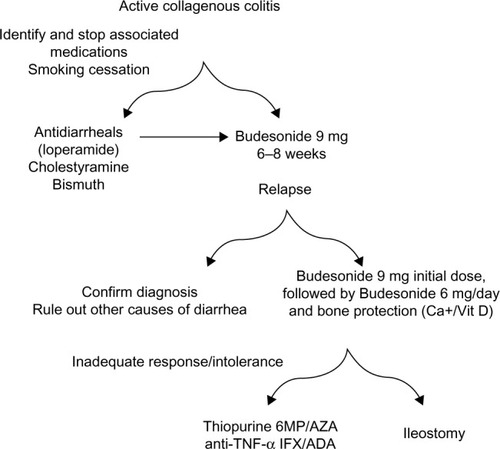

Figure 1 European Microscopic Colitis Group algorithm for the management of collagenous colitis.

Abbreviations: 6MP, 6 mercaptopurine; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; IFX, infliximab; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; Vit D, vitamin D.

An approach to those with mild symptoms who do not respond to budesonide is to use a combination treatment with loperamide and cholestyramine. If symptoms persist despite this strategy Bismuth subsalicylate could be considered, but availability is limited and use is limited by nephrotoxicity.Citation82

Cholestyramine

Bile acid diarrhea is commonly associated with CC and in those patients with concomitant bile acid malabsorption cholestryramine is an effective therapy.Citation83,Citation84

Rates of bile acid malabsorption and the effect of bile acid sequestration were studied in 28 patients with CC, 12 (44%) had evidence of bile acid malabsorption. Bile acid treatment resulted in rapid resolution of symptoms in 11/12 patients with concomitant bile acid malabsorption compared with 10/15 (67%) without.Citation85 The authors conclude that bile acid malabsorption commonly occurs in CC patients and may contribute to the pathogenesis of colonic inflammation, bile acid therapy should be considered given higher response rates and no serious side effects.

Forty-one patients with LC and 23 with CC were randomized to mesalazine with or without cholestyramine for 6 months. Diarrhea was resolved within 2 weeks in 54 patients (84.37%).

In those with CC clinical and histological remission was achieved in 91.3% of patients, with better results seen in those randomized to both mesalazine and cholestyramine.Citation86

Furthermore, budesonide treatment has been shown to increase bile acid absorption in patients with CC and this reduction in colonic bile load may in part explain its efficacy.Citation87

Amino salicylates

Previously, there was only anecdotal evidence to support the use of sulfasalazine and mesalazine therapy, but recently they have been studied in controlled trials.

Calabrese et al randomized 64 patients with MC to 6 months’ treatment with mesalazine 2.4 g/day or mesalazine 2.4 g/day and cholestyramine 4 g/day. The high-remission rate was seen in both treatment arms, and 85% of patients with LC and 91% of patients with CC were in remission at the end of the study.Citation86 However, a placebo-controlled, randomized trial of mesalazine 3 g/day for 8 weeks as a short-term induction agent was no more efficacious than placebo.Citation77

As mentioned in the study by Miehlke et al, of patients with active CC randomized to budesonide (9 mg), mesalazine (3 g), or placebo therapy, rates of remission with mesalamine and placebo were similar after 8 weeks (32% and 38%, respectively).Citation77 An older study of 163 patients with CC demonstrated remission rates of 40% with mesalamine or olsalazine.Citation33

Antibiotics/probiotics

There are no controlled data to advocate the use of antibiotics, but metronidazole or erythromycin have previously been used.

Bismuth has anti-inflammatory, antidiarrheal, and anti-biotic properties but is not widely available due to concerns regarding nephrotoxicity.Citation81 In a small open label trial, bismuth therapy was shown to induce remission of symptoms and disappearance of the collagen band in patients with CC,Citation88 treatment was well tolerated with no serious side effects.

Probiotic treatment and the role of the intestinal micro-biome requires further assessment.Citation89

Madisch et al studied the effect of the Boswellia serrate extract (BSE) on symptoms, QOL, and histology in 31 patients with CC and found that after 6 weeks, the proportion of patients in clinical remission was higher in the BSE group than in the placebo group (63.6% vs 26.7%, P=0.04).Citation90 Larger trials are required to confirm the clinical efficacy of BSE in MC.

Immunomodulators

In the small number of patients with persistent symptoms despite budesonide and antidiarrheal agents, immunomodulator therapy may be considered.Citation32,Citation52,Citation91

Azathioprine induced partial or complete remission in eight of nine patients with MC in an open study,Citation92 further-more, a retrospective series, demonstrated an overall response rate to thiopurines of 41% (19 of 46), but azathioprine was poorly tolerated accompanied by a high frequency of side effects, leading to treatment cessation.Citation93

Methotrexate

An open case series of nine patients with budesonide refractory CC demonstrated no clinical effect of methotrexate.Citation94 Methotrexate therapy 15 mg subcutaneously was administered weekly for 6 weeks and increased to 25 mg thereafter if symptoms persisted. No patient experienced clinical remission or improved QOL and four patients withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

Biologics

There are no randomized trials studying the role of biologics in the management of CC, but recent case reports have suggested a role for anti-TNFα therapies (infliximab and adalimumab) in CC refractory to budesonide and the author recommends considering biologic therapy before colectomy.Citation95–Citation97

Miscellaneous

Other agents have been studied including octreotide and verapamil, but with no consistent beneficial effect.Citation98,Citation99

Surgery

Surgery should only be considered in those refractory to medical management.Citation100–Citation102 Diversion of the fecal stream has been shown to induce histopathological remission in CC but upon restoration of flow the collagen band returned.Citation102 This implies that a luminal factor contributes to inflammation and for some patients with refractory disease ileostomy may be an appropriate therapeutic strategy. Surgical options include split ileostomy and subtotal colectomy and success has been reported with total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis.Citation101,Citation103 Considering advances in medical therapy the indication for surgery is limited.

Conclusion

CC is an increasingly encountered cause of chronic diarrhea. It is predominantly a benign and self-limiting disorder. The introduction of budesonide has revolutionized treatment of this lesser studied inflammatory bowel disease, however, higher relapse rates are seen upon withdrawal and the management of chronic active colitis remains a challenge. Ongoing trials will address the safety and efficacy of low-dose maintenance therapy. For those with disease unresponsive to budesonide, case reports and case series support the role of biologic agents.

The author recommends screening for concomitant celiac disease and thyroid dysfunction in those with ongoing diarrhea. Smoking cessation is recommended. Patients should be advised to avoid NSAIDs and if possible, discontinue medications associated with MC.

Further insight into the pathogenesis of collagen deposition and the mucosal immunological changes will facilitate improved therapy and may identify biomarkers of disease activity.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FineKDSeidelRHDoKThe prevalence, anatomic distribution, and diagnosis of colonic causes of chronic diarrheaGastrointest Endosc200051331832610699778

- KoulaouzidisASaeedAADistinct colonoscopy findings of microscopic colitis: not so microscopic after all?World J Gastroenterol201117374157416522072846

- LindstromCG‘Collagenous colitis’ with watery diarrhoea – a new entity?Pathol Eur19761118789934705

- FineKDMeyerRLLeeELThe prevalence and causes of chronic diarrhea in patients with celiac sprue treated with a gluten-free dietGastroenterology19971126183018389178673

- FineKDDoKSchulteKHigh prevalence of celiac sprue-like HLA-DQ genes and enteropathy in patients with the microscopic colitis syndromeAm J Gastroenterol20009581974198210950045

- VillanacciVCasellaGBassottiGThe spectrum of drug-related colitides: important entities, though frequently overlookedDig Liver Dis43752352821324756

- CappellMSColonic toxicity of administered drugs and chemicalsAm J Gastroenterol20049961175119015180742

- ChandeNMcDonaldJWMacdonaldJKInterventions for treating collagenous colitis: a Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group systematic review of randomized trialsAm J Gastroenterol200499122459246515571596

- O’TooleACossAHolleranGMicroscopic colitis: clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes in an Irish populationInt J Colorectal Dis201429779980324743846

- BenchimolEIKirschRVieroSGriffithsAMCollagenous colitis and eosinophilic gastritis in a 4-year old girl: a case report and review of the literatureActa Paediatr20079691365136717718794

- CamareroCLeonFColinoECollagenous colitis in children: clinicopathologic, microbiologic, and immunologic featuresJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200337450851314508225

- GentileNMKhannaSLoftusEVJrThe epidemiology of microscopic colitis in Olmsted County from 2002 to 2010: a population-based studyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201412583884224120840

- WickbomABohrJErikssonSUdumyanRNyhlinNTyskCStable incidence of collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis in Orebro, Sweden, 1999–2008: a continuous epidemiologic studyInflamm Bowel Dis201319112387239323945183

- TongJZhengQZhangCLoRShenJRanZIncidence, prevalence, and temporal trends of microscopic colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol20151102265276 quiz 7725623658

- BonderupOKWighTNielsenGLPedersenLFenger-GronMThe epidemiology of microscopic colitis: a 10-year pathology-based nationwide Danish cohort studyScand J Gastroenterol201550439339825645623

- ParkYSBaekDHKimWHClinical characteristics of microscopic colitis in Korea: prospective multicenter study by KASIDGut Liver20115218118621814598

- MisraVMisraSPDwivediMSinghPAAgarwalVMicroscopic colitis in patients presenting with chronic diarrheaIndian J Pathol Microbiol2010531151920090215

- HilmiIHartonoJLPailoorJMahadevaSGohKLLow prevalence of ‘classical’ microscopic colitis but evidence of microscopic inflammation in Asian irritable bowel syndrome patients with diarrhoeaBMC Gastroenterol2013138023651739

- BohrJWickbomAHegedusANyhlinNHultgren HornquistETyskCDiagnosis and management of microscopic colitis: current perspectivesClin Exp Gastroenterol2014727328425170275

- BarmeyerCErkoIFrommAIon transport and barrier function are disturbed in microscopic colitisAnn N Y Acad Sci2012125814314822731727

- BurgelNBojarskiCMankertzJZeitzMFrommMSchulzkeJDMechanisms of diarrhea in collagenous colitisGastroenterology2002123243344312145796

- van TilburgAJLamHGSeldenrijkCAFamilial occurrence of collagenous colitis. A report of two familiesJ Clin Gastroenterol19901232792852362097

- LakatosGSiposFMihellerPThe behavior of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in lymphocytic colitis, collagenous colitis and ulcerative colitisPathol Oncol Res2012181859121678108

- KoskelaRMKarttunenTJNiemelaSELehtolaJKIlonenJKarttunenRAHuman leucocyte antigen and TNFalpha polymorphism association in microscopic colitisEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200820427628218334870

- ErimTAlazmiWMO’LoughlinCJBarkinJSCollagenous colitis associated with Clostridium difficile: a cause effect?Dig Dis Sci20034871374137512870798

- MakinenMNiemelaSLehtolaJKarttunenTJCollagenous colitis and Yersinia enterocolitica infectionDig Dis Sci1998436134113469635629

- NarayaniRIBurtonMPYoungGSResolution of collagenous colitis after treatment for Helicobacter pyloriAm J Gastroenterol200297249849911866305

- DaumSFossHDSchuppanDRieckenEOZeitzMUllrichRSynthesis of collagen I in collagenous sprueClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20064101232123616979955

- AignerTNeureiterDMullerSKuspertGBelkeJKirchnerTExtra-cellular matrix composition and gene expression in collagenous colitisGastroenterology199711311361439207271

- Stahle-BackdahlMMaimJVeressBBenoniCBruceKEgestenAIncreased presence of eosinophilic granulocytes expressing transforming growth factor-beta1 in collagenous colitisScand J Gastroenterol200035774274610972179

- AndresenLJorgensenVLPernerAHansenAEugen-OlsenJRask-MadsenJActivation of nuclear factor kappaB in colonic mucosa from patients with collagenous and ulcerative colitisGut200554450350915753535

- MunchAAustDBohrJMicroscopic colitis: current status, present and future challenges: statements of the European Microscopic Colitis GroupJ Crohns Colitis20126993294522704658

- BohrJTyskCErikssonSAbrahamssonHJarnerotGCollagenous colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation and treatment in 163 patientsGut19963968468519038667

- BohrJLarssonLGErikssonSJarnerotGTyskCColonic perforation in collagenous colitis: an unusual complicationEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200517112112415647652

- AllendeDSTaylorSLBronnerMPColonic perforation as a complication of collagenous colitis in a series of 12 patientsAm J Gastroenterol2008103102598260418702648

- TontiniGEPastorelliLSpinaLMicroscopic colitis and colorectal neoplastic lesion rate in chronic nonbloody diarrhea: a prospective, multicenter studyInflamm Bowel Dis201420588289124681653

- StoicescuABecheanuGDumbravaMGheorgheCDiculescuMMicroscopic colitis – a missed diagnosis in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeMaedica (Buchar)2012713923118812

- PatelPBercikPMorganDGPrevalence of organic disease at colonoscopy in patients with symptoms compatible with irritable bowel syndrome: cross-sectional surveyScand J Gastroenterol201550781682325636675

- AbboudRPardiDSTremaineWJKammerPPSandbornWJLoftusEVJrSymptomatic overlap between microscopic colitis and irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective studyInflamm Bowel Dis201319355055323380937

- LimsuiDPardiDSCamilleriMSymptomatic overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and microscopic colitisInflamm Bowel Dis200713217518117206699

- HjortswangHTyskCBohrJHealth-related quality of life is impaired in active collagenous colitisDig Liver Dis201143210210920638918

- NyhlinNWickbomAMontgomerySMTyskCBohrJLong-term prognosis of clinical symptoms and health-related quality of life in microscopic colitis: a case-control studyAliment Pharmacol Ther201439996397224612051

- CapursoGMarignaniMAttiliaFLansoprazole-induced microscopic colitis: an increasing problem? Results of a prospective case-series and systematic review of the literatureDig Liver Dis201143538038521195042

- RiddellRHTanakaMMazzoleniGNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a possible cause of collagenous colitis: a case-control studyGut19923356836861612488

- GuagnozziDLucendoAJAngueiraTGonzalez-CastilloSTeniasJMDrug consumption and additional risk factors associated with microscopic colitis: case-control studyRev Esp Enferm Dig2015107634735326031862

- Fernandez-BanaresFde SousaMRSalasAEpidemiological risk factors in microscopic colitis: a prospective case-control studyInflamm Bowel Dis201319241141723344243

- VigrenLSjobergKBenoniCIs smoking a risk factor for collagenous colitis?Scand J Gastroenterol201146111334133921854096

- YenEFPokhrelBDuHCurrent and past cigarette smoking significantly increase risk for microscopic colitisInflamm Bowel Dis201218101835184122147506

- Fernandez-BanaresFde SousaMRSalasAImpact of current smoking on the clinical course of microscopic colitisInflamm Bowel Dis20131971470147623552765

- StewartMAndrewsCNUrbanskiSBeckPLStorrMThe association of coeliac disease and microscopic colitis: a large population-based studyAliment Pharmacol Ther201133121340134921517923

- WildtSNordgaard-LassenIBendtsenFRumessenJJMetabolic and inflammatory faecal markers in collagenous colitisEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200719756757417556903

- TyskCWickbomANyhlinNErikssonSBohrJRecent advances in diagnosis and treatment of microscopic colitisAnn Gastroenterol201124425326224713787

- Cruz-CorreaMMilliganFGiardielloFMCollagenous colitis with mucosal tears on endoscopic insufflation: a unique presentationGut200251460012235088

- van EijkRLBacDJMucosal tears and colonic perforation in a patient with collagenous colitisEndoscopy201446Suppl 1 UCTNE6424523187

- MagroFLangnerCDriessenAEuropean consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Crohns Colitis201371082785123870728

- O’MahonyOHBurgoyneMGoingJJSpecific histological abnormalities are more likely in biopsies of endoscopically normal large bowel after the age of 60 yearsHistopathology20126161209121322882180

- GeboesKLymphocytic, collagenous and other microscopic colitides: pathology and the relationship with idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseasesGastroenterol Clin Biol2008328–968969418538968

- LangnerCAustDEnsariAHistology of microscopic colitis-review with a practical approach for pathologistsHistopathology201566561362625381724

- TanakaMMazzoleniGRiddellRHDistribution of collagenous colitis: utility of flexible sigmoidoscopyGut199233165701740280

- JessurunJYardleyJHGiardielloFMHamiltonSRBaylessTMChronic colitis with thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer (collagenous colitis): histopathologic findings in 15 patientsHum Pathol19871888398483610134

- CarpenterHATremaineWJBattsKPCzajaAJSequential histologic evaluations in collagenous colitis. Correlations with disease behavior and sampling strategyDig Dis Sci19923712190319091361906

- ChettyRGovenderDLymphocytic and collagenous colitis: an overview of so-called microscopic colitisNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol20129420921822349169

- MunchALangnerCMicroscopic colitis: clinical and pathologic perspectivesClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201513222823624407107

- YantissRKOdzeRDOptimal approach to obtaining mucosal biopsies for assessment of inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tractAm J Gastroenterol2009104377478319209164

- HjortswangHTyskCBohrJDefining clinical criteria for clinical remission and disease activity in collagenous colitisInflamm Bowel Dis200915121875188119504614

- BeaugerieLPardiDSReview article: drug-induced microscopic colitis – proposal for a scoring system and review of the literatureAliment Pharmacol Ther200522427728416097993

- WallGCSchirmerLLPageMJPharmacotherapy for microscopic colitisPharmacotherapy200727342543317316153

- KinghamJGMicroscopic colitisGut19913232342352013415

- SlothHBisgaardCGroveACollagenous colitis: a prospective trial of prednisolone in six patientsJ Intern Med199122954434462040870

- GentileNMAbdallaAAKhannaSOutcomes of patients with microscopic colitis treated with corticosteroids: a population-based studyAm J Gastroenterol2013108225625923295275

- MunckLKKjeldsenJPhilipsenEFischer HansenBIncomplete remission with short-term prednisolone treatment in collagenous colitis: a randomized studyScand J Gastroenterol200338660661012825868

- ChandeNMacDonaldJKMcDonaldJWInterventions for treating microscopic colitis: a Cochrane Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Functional Bowel Disorders Review Group systematic review of randomized trialsAm J Gastroenterol20091041235241 quiz 4, 4219098875

- MiehlkeSMadischAVossCLong-term follow-up of collagenous colitis after induction of clinical remission with budesonideAliment Pharmacol Ther20052211–121115111916305725

- MiehlkeSHeymerPBethkeBBudesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trialGastroenterology2002123497898412360457

- BonderupOKHansenJBBirket-SmithLVestergaardVTeglbjaergPSFallingborgJBudesonide treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial with morphometric analysisGut200352224825112524408

- StewartMJSeowCHStorrMAPrednisolone and budesonide for short- and long-term treatment of microscopic colitis: systematic review and meta-analysisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201191088189021699817

- MiehlkeSMadischAKupcinskasLBudesonide is more effective than mesalamine or placebo in short-term treatment of collagenous colitisGastroenterology2014146512221230e1e224440672

- BaertFSchmitAD’HaensGBudesonide in collagenous colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial with histologic follow-upGastroenterology20021221202511781276

- MadischAHeymerPVossCOral budesonide therapy improves quality of life in patients with collagenous colitisInt J Colorectal Dis200520431231615549326

- MiehlkeSHansenJBMadischARisk factors for symptom relapse in collagenous colitis after withdrawal of short-term budesonide therapyInflamm Bowel Dis201319132763276724216688

- MunchABohrJMiehlkeSLow-dose budesonide for maintenance of clinical remission in collagenous colitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, 12-month trialGut2014 Epub 2014 Nov 25

- SarikayaMSevincAUluRAtesFAriFBismuth subcitrate nephrotoxicity. A reversible cause of acute oliguric renal failureNephron200290450150211961412

- Fernandez-BanaresFSalasAEsteveMEspinosJForneMViverJMCollagenous and lymphocytic colitis. Evaluation of clinical and histological features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-upAm J Gastroenterol200398234034712591052

- UngKAKilanderANilssonOAbrahamssonHLong-term course in collagenous colitis and the impact of bile acid malabsorption and bile acid sequestrants on histopathology and clinical featuresScand J Gastroenterol200136660160911424318

- UngKAGillbergRKilanderAAbrahamssonHRole of bile acids and bile acid binding agents in patients with collagenous colitisGut200046217017510644309

- CalabreseCFabbriAAreniAZahlaneDScialpiCDi FeboGMesalazine with or without cholestyramine in the treatment of microscopic colitis: randomized controlled trialJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200722680981417565633

- Bajor A1KAGälmanCRudlingMUngKABudesonide treatment is associated with increased bile acid absorption in collagenous colitisAliment Pharmacol Ther20062411–121643164917094773

- FineKDLeeELEfficacy of open-label bismuth subsalicylate for the treatment of microscopic colitisGastroenterology1998114129369428215

- WildtSMunckLKVinter-JensenLProbiotic treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. LactisInflamm Bowel Dis200612539540116670529

- MadischAMiehlkeSEicheleOBoswellia serrata extract for the treatment of collagenous colitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trialInt J Colorectal Dis200722121445145117764013

- PardiDSKellyCPMicroscopic colitisGastroenterology201114041155116521303675

- PardiDSLoftusEVJrTremaineWJSandbornWJTreatment of refractory microscopic colitis with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurineGastroenterology200112061483148411313319

- MunchAFernandez-BanaresFMunckLKAzathioprine and mercaptopurine in the management of patients with chronic, active microscopic colitisAliment Pharmacol Ther201337879579823432370

- MunchABohrJVigrenLTyskCStromMLack of effect of methotrexate in budesonide-refractory collagenous colitisClin Exp Gastroenterol2013614915224039441

- EsteveMMahadevanUSainzERodriguezESalasAFernandez-BanaresFEfficacy of anti-TNF therapies in refractory severe microscopic colitisJ Crohns Colitis20115661261822115383

- PolaSFahmyMEvansETippsASandbornWJSuccessful use of infliximab in the treatment of corticosteroid dependent collagenous colitisAm J Gastroenterol2013108585785823644970

- MunchAIgnatovaSStromMAdalimumab in budesonide and methotrexate refractory collagenous colitisScand J Gastroenterol2012471596322149977

- FisherNCTuttASimEScarpelloJHGreenJRCollagenous colitis responsive to octreotide therapyJ Clin Gastroenterol19962343003018957735

- ScheidlerMDMeiselmanMUse of verapamil for the symptomatic treatment of microscopic colitisJ Clin Gastroenterol200132435135211276283

- BowlingTEPriceABal-AdnaniMFaircloughPDMenzies-GowNSilkDBInterchange between collagenous and lymphocytic colitis in severe disease with autoimmune associations requiring colectomy: a case reportGut19963857887918707130

- WilliamsRAGelfandDVTotal proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis to successfully treat a patient with collagenous colitisAm J Gastroenterol2000958214710950095

- JarnerotGTyskCBohrJErikssonSCollagenous colitis and fecal stream diversionGastroenterology199510924494557615194

- MunchASoderholmJDWallonCOstAOlaisonGStromMDynamics of mucosal permeability and inflammation in collagenous colitis before, during, and after loop ileostomyGut20055481126112816009686