Abstract

Purpose

Injection with the bulking agent consisting of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid/dextranomer (NASHA®/Dx) is well tolerated and efficacious for the treatment of fecal incontinence (FI); however, the patient population that may derive maximum benefit has not been established. This post hoc responder analysis assessed demographic and baseline characteristics predictive of responsiveness to NASHA/Dx treatment.

Methods

Adults with a Cleveland Clinic Florida fecal incontinence score (CCFIS) ≥10 were randomized to receive NASHA/Dx or sham treatment. The primary end point was response to treatment (ie, decrease from baseline of ≥50% in number of FI episodes) at 6 months; a prespecified secondary end point was change in fecal incontinence quality of life (FIQL) score at 6 months. Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed for baseline and demographic characteristics and prior FI treatments.

Results

Overall, response to treatment was significantly greater with NASHA/Dx versus sham injection (52.7% vs 32.1%; P=0.0089). All subgroups analyzed demonstrated evidence of improvement, favoring NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment for both response to treatment and change in the FIQL coping/behavior subscale score. For the primary end point, a significantly greater percentage of patients with CCFIS ≤15, FI symptoms ≤5 years’ duration, or obstetric causes of FI responded to NASHA/Dx treatment versus patients receiving sham treatment (51.1% vs 28.3%, P=0.0169; 55.4% vs 25.7%, P=0.0026; and 53.6% vs 23.1%, P=0.0191, respectively). The mean change in the FIQL coping/behavior score significantly favored NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment for patients with CCFIS ≤15 (P=0.0371), FI symptoms ≤5 years’ duration (P=0.0289), or obstetric causes of FI (P=0.0384). Patients without a history of specific FI treatments (eg, antidiarrheal medications, biofeedback, surgery) were more likely to respond to NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment for both end points.

Conclusion

Although all subgroups analyzed showed evidence of quantitative and qualitative benefit from NASHA/Dx therapy, patients with characteristics indicative of mild-to-moderate FI may exhibit the greatest benefit.

Introduction

The prevalence of fecal incontinence (FI) is ~8.4% among noninstitutionalized adults, representing about 19 million people in the US,Citation1,Citation2 and increases with age, with ~17% of adults ≥65 years and as many as 50% of nursing home residents affected.Citation3–Citation6 FI is often a multifactorial disorder with a diverse etiology.Citation7 For example, a grade 3 or 4 episiotomy was an obstetric risk factor for pelvic floor injury, even decades after childbirth, in a population-based study comparing women with and without FI.Citation8 However, anal sphincter damage or injury unrelated to childbirth and neuromuscular and muscular diseases are also potential causes of FI.Citation7 The clinical symptoms of FI are compounded by negative psychosocial effects (eg, diminished self-esteem, social withdrawal, and anxiety), and total costs associated with FI (ie, direct medical and nonmedical costs, indirect costs) average $4,110 annually per patient in the US, with substantially higher costs in certain cases.Citation3,Citation9

Treatment options for patients with FI include pharmacologic and surgical approaches as well as dietary modification and alternative therapies (eg, biofeedback).Citation10,Citation11 The choice of treatment modality depends on multiple factors, including the cause(s) of incontinence; degree of impairment and impact on functional status; the setting (eg, community or nursing home); comorbidities; and, ultimately, patient preference.Citation10 Dietary modification, often coupled with fiber supplementation and bowel habit training, is recommended as a first-line treatment for patients with FI, and patients with diarrhea or loose stools may gain benefit from antidiarrheal medication as an early treatment measure.Citation12 Biofeedback is a potentially efficacious option in patients with mild-to-moderate FI but is largely dependent on proper training and patient adherence.Citation11 For some identifiable anal sphincter defects, surgical repair may be considered early in the treatment algorithm.Citation11,Citation13 The most common surgical intervention for patients with FI resulting from an injury to the external anal sphincter is sphincteroplasty;Citation14 however, studies have failed to demonstrate long-term durability of this treatment.Citation15–Citation17 It is interesting to note that current trends suggest that surgery is being reserved for patients who have more severe FI and/or those whose FI has been refractory to other treatments,Citation11 but it is unclear whether surgical intervention in general, which may be associated with increased morbidity and length of hospitalization, is more efficacious in the long term than nonsurgical (eg, minimally invasive) FI treatment approaches.Citation18

Perianal injection of bulking agents has been advanced as a minimally invasive treatment option for patients with FI, and studies evaluating a number of different bulking materials have been reviewed recently.Citation19 The bulking agent consisting of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid/dextranomer (NASHA®/Dx) is a relatively newer option that has been characterized as being efficacious in several uncontrolled studiesCitation20–Citation23 and randomized, controlled studies.Citation24,Citation25 In one randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical study of NASHA/Dx in 206 patients with FI, 52.7% of patients in the NASHA/Dx group had a decrease from baseline of ≥50% in the number of FI episodes compared with 32.1% of patients in the sham treatment group at 6 months post-injection.Citation25 Although almost all patients who received therapy derived at least some benefit from injection, it is unclear whether certain demographics, baseline characteristics, and/or previous FI treatments may be predictive of response to treatment with bulking agents such as NASHA/Dx.Citation19 Studies of other treatments for FI have suggested that baseline and demographic characteristics, such as age, severity of disease, and type of FI, may be predictive of response.Citation20,Citation26–Citation29 Accordingly, we conducted a post hoc responder analysis of data from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trialCitation25 to examine demographic and baseline characteristics, including previous treatments, that might predict optimal responsiveness to NASHA/Dx treatment.

Methods

Patients and study design

Details of the patient population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and study design have been described previously.Citation25 Briefly, patients 18 to 75 years of age with FI (Cleveland Clinic Florida fecal incontinence score [CCFIS] ≥10) and ≥4 episodes of FI during a 2-week time frame from the US and Europe were randomized (2:1) to receive transanal injections of NASHA/Dx or sham treatment. Immediately before receiving treatment, patients received a cleansing enema. Using an anoscope, four 1 mL injections were administered (1 mL in each quadrant [posterior, left lateral, anterior, and right lateral] of the submucosa of the anal canal), ~5 mm above the dentate line, without the use of anesthesia. The procedure for patients receiving sham treatment was similar, except that no substance was injected. At 1 month, patients with no persistent adverse events but persistent FI (CCFIS ≥10) were offered one retreatment procedure. Patients and study investigators were blinded to treatment administered during the first 6 months post-injection. During this 6-month period, patients underwent a clinical anorectal assessment and proctoscopy at 3 and 6 months.Citation25 The study was approved by the ethics committees and institutional review boards of all participating centers. All patients provided signed, informed consent.

Assessments

The primary efficacy end point was response to treatment, defined as a decrease from baseline of ≥50% in the number of FI episodes at 6 months.Citation25 A secondary end point was assessment of the fecal incontinence quality of life (FIQL) scores, which include four subscales (ie, lifestyle, coping/behavior, depression/self-perception, and embarrassment)Citation30 at 6 months. The primary end point and the FIQL coping/behavior subscale, chosen based on the significant improvement reported during the pivotal study,Citation25 were further analyzed by subgroups, which comprised baseline and demographic characteristics (ie, sex, age, body mass index, severity of FI, duration of FI, history of urinary incontinence, number of FI episodes, and cause of FI) and use of prior FI treatment modalities (ie, dietary avoidance, fiber supplementation, antidiarrheal medications, bowel habit training, biofeedback, and surgery).

Statistical analyses

For analysis of the primary end point, efficacy was evaluated in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population for each of the subgroups. As prespecified in the study protocol, odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were generated for each comparison between NASHA/Dx and sham treatment using the logistic model, with baseline number of FI episodes, sex, and treatment center as covariates. For the primary end point, missing data were handled with the primary imputation method. In this prespecified scheme, baseline diary data were carried forward to 6 months for patients who were withdrawn from the study for any reason before or at the 6-month visit and did not have valid 6-month diary data. If a patient had not withdrawn from the study before the 6-month visit but had no valid diary data at 6 months, the most recent data were carried forward for them. For analysis of the FIQL coping/behavior subscale, change from baseline to 6 months was calculated in the ITT population for each subgroup using the prespecified imputation method of last observation carried forward. Least-squares (LS) means were estimated for NASHA/Dx and sham treatments in a given subgroup using the analysis of covariance model with baseline FIQL subscale score, sex, and treatment center as covariates. Differences in LS means, corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and P-values were generated from the same analysis model.

Results

Patient population

A total of 206 patients (NASHA/Dx, n=136; sham, n=70) were included in the ITT population. Demographic and baseline characteristics of the overall population were similar between the two treatment groups and have been previously reported.Citation25 Patients in the NASHA/Dx and sham treatment groups were mostly female (90% vs 87%, respectively) and of similar age (mean 61.8 vs 60.1 years, respectively), and had a similar body mass index (mean 25.8 vs 26.4, respectively). Baseline CCFIS (mean 14.0 vs 13.0, respectively) and number of FI episodes (15.0 vs 12.5, respectively) were comparable between groups. At least half of patients receiving NASHA/Dx or sham treatment had previously undergone dietary modification (62% vs 70%, respectively), fiber supplementation (81% vs 73%, respectively), use of antidiarrheal drugs (60% vs 69%, respectively), or biofeedback (60% vs 50%, respectively) as treatment for FI. Only 15% and 11% of patients receiving NASHA/Dx or sham treatment, respectively, had undergone prior surgical intervention for FI.

Efficacy

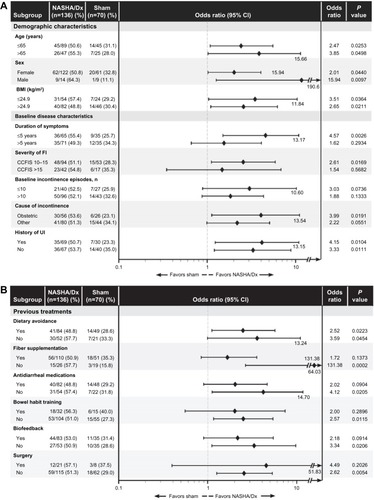

The data for each subgroup analyzed generally favored NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment for the primary end point (). A significantly greater percentage of patients with a CCFIS of 10–15, indicative of less severe disease,Citation28 responded to treatment with NASHA/Dx compared with patients receiving sham treatment (51.1% vs 28.3%, respectively; P=0.0169); a greater percentage of patients with CCFIS >15, or more severe FI, responded to treatment with NASHA/Dx compared with sham treatment, but this finding was not significant (54.8% vs 35.3%, respectively; P=0.5682). Patients with FI symptoms of ≤5 years’ duration had a significantly higher response rate with NASHA/Dx compared with sham treatment (55.4% vs 25.7%, respectively; P=0.0026). A greater percentage of patients with obstetric causes of FI responded to treatment with NASHA/Dx compared with sham treatment (53.6% vs 23.1%, respectively; P=0.0191).

Figure 1 Patient response (ie, a decrease from baseline of ≥50% in the number of fecal incontinence episodes) to NASHA/Dx or sham treatment at 6 months.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CCFIS, Cleveland Clinic Florida fecal incontinence score; FI, fecal incontinence; NASHA/Dx, non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid/dextranomer; UI, urinary incontinence.

While all patients were required to fail at least some form of previous therapy, in general, patients who had not received prior FI treatment via antidiarrheal medications, bowel habit training, biofeedback, or surgery were significantly more likely to respond to NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment (). With the exception of dietary avoidance, no significant differences were observed in patients with a medical history positive for other individual FI treatment.

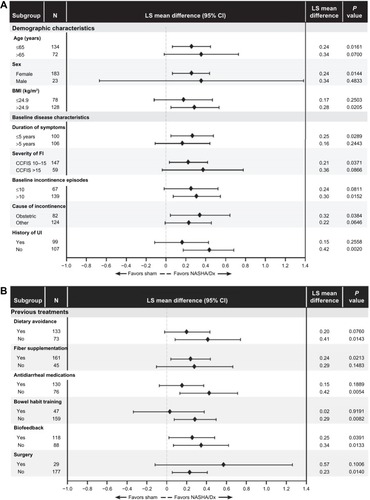

Overall, subgroup analyses of the change from baseline to 6 months in the FIQL coping/behavior subscale favored treatment with NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment (). For patients with a CCFIS of 10 to 15 and duration of disease ≤5 years, indicators of mild-to-moderate disease, treatment with NASHA/Dx was significantly favored compared with treatment with sham (LS means difference in FIQL subscale score, 0.21 [P=0.0371] and 0.25 [P=0.0289], respectively). Patients with an obstetric etiology of FI had a greater change in the FIQL coping/behavior subscale following treatment with NASHA/Dx compared with sham treatment (LS means difference, 0.32; P=0.0384). Patients without a history of treatment consisting of any one or more of antidiarrheal medications, bowel habit training, biofeedback, or surgery were also significantly more likely to respond to NASHA/Dx versus sham treatment ().

Figure 2 Change in FIQL coping/behavior subscale score from baseline to 6 months in patients receiving NASHA/Dx or sham treatment.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CCFIS, Cleveland Clinic Florida fecal incontinence score; CI, confidence interval; FI, fecal incontinence; FIQL, fecal incontinence quality of life; LS, least-squares; NASHA/Dx, non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid/dextranomer; UI, urinary incontinence.

Discussion

Results of a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial in patients with FI showed that injection with NASHA/Dx decreased the number of FI episodes by at least 50% in 52.7% of patients at 6 months compared with 32.1% of patients receiving sham treatment.Citation25 Previous studies have suggested that treatment response in patients with FI may be affected by demographic and baseline disease characteristics, including age, severity of disease, and type of FI.Citation20,Citation26 Because clinical trials may be designed to select for a homogeneous population of patients with FI, rather than for specific baseline or demographic characteristics,Citation31 post hoc analyses may provide insight into the profile of patients who may derive the maximum benefit from a specific treatment. This post hoc responder analysis of data from the randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical study of NASHA/Dx in patients with FICitation25 was conducted to examine demographic and baseline disease characteristics, including previous FI treatments, that might be predictive of treatment success.

Regardless of subgroup analyzed, there was a general trend in favor of NASHA/Dx versus sham for the treatment of FI. Interestingly, patients who had symptoms consistent with mild-to-moderate FI at baseline (ie, CCFIS ≤15,Citation28 duration of FI ≤5 years, exposure to few prior FI treatment modalities), and those in whom the primary cause of FI was obstetric-related were more likely to benefit from treatment with NASHA/Dx compared with sham treatment. A similar profile of subgroup responsiveness was observed for the FIQL coping/behavior subscale, where patients with mild-to-moderate FI at baseline (CCFIS ≤15, duration of FI ≤5 years, exposure to few prior FI treatment modalities) and an obstetric etiology of FI had a significant change in the FIQL coping/behavior subscale score at 6 months. These data suggest that the optimal patient population for treatment with NASHA/Dx may be patients with mild-to-moderate FI, and that reductions in FI episodes may translate into meaningful enhancements in some FI-related quality of life measures. It should be noted that there were no changes in other FIQL subscales (ie, lifestyle, depression, and self-perception) at 6 months in the overall population,Citation25 although significant improvements were observed at 12 months in all of these domains.

The potential treatment benefit observed with NASHA/Dx in patients who had an obstetric FI etiology is interesting and may be related to the nature of the trauma incurred during childbirth. As a neurologic etiology of FI following childbirth (eg, pudendal neuropathy) is different than a sphincter tear during childbirth, it would be valuable to further understand potential treatment benefits for this obstetric-related FI population when subgrouped by etiology. However in the current study, additional data on the etiology of obstetric trauma were unavailable for further analysis of potential differences. Maintenance of anal pressure in the anal canal is important for continence,Citation32 as anal pressure has been shown to decrease in many patients following vaginal delivery for at least 6 to 10 weeks compared with anal pressure before childbirth.Citation33 Further, mechanical or neurologic damage to the anal sphincter following vaginal delivery (eg, forceps delivery, tears) is not uncommon and has been shown to affect 35% of patients with no previous pregnancies in one study;Citation32,Citation34 instrumentation-assisted vaginal delivery has been significantly associated with FI 5 to 10 years after childbirth.Citation35 These data are not entirely surprising, given that normal anorectal function relies on the neuromuscular integrity of the anal canal and surrounding sphincter muscle.Citation32 The benefit observed in patients with obstetric damage may be related, at least in part, to the mechanism of action of NASHA/Dx. The dextranomer microspheres establish a scaffold for fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and collagen to grow around, stabilizing the tissue near the injection sites, and sealing the anal canal to an extent,Citation20,Citation21,Citation36–Citation38 thus restoring anal pressure.Citation32,Citation37 Obstetric trauma and injury is a risk factor for FI,Citation39 and these findings suggest that this patient population may be likely to benefit from treatment with NASHA/Dx.

The inclusion of a sham control arm in this study was a strength that allowed for control of selection and response biases by investigators and patients. The assessment of subgroup responsiveness under such randomized, controlled conditions was, therefore, clinically meaningful. Nevertheless, this analysis has limitations. Due to the post hoc nature of the assessments, one limitation is that the study was not specifically powered to test for efficacy in various subgroups. Further, some of the subgroups had a small number of patients, thus limiting ability to interpret the results. Another limitation is that durability of response with NASHA/Dx has been shown for up to 3 years,Citation40 but data for sham treatment beyond 6 months are lacking in the current study because patients in the sham treatment arm were offered open-label treatment with NASHA/Dx after the short (6-month) blinding period and were excluded from further analysis.Citation25 Finally, given that post hoc analyses are hypothesis-generating endeavors, the results described herein warrant a well-powered, prospective, controlled study in patients with mild-to-moderate FI.

Conclusion

Injection with NASHA/Dx is an efficacious treatment for patients with FI, and data suggest that patients with mild-to-moderate FI may represent the population that would be most likely to respond to treatment. Future prospective studies are warranted to support these findings and help identify the factors that determine responsiveness to injectable bulking agents.

Acknowledgments

Technical editorial and medical writing assistance was provided, under the direction of the authors, by Sophie Bolick, PhD, for Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA, USA. Funding for this support was provided by Salix, a Division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, Bridgewater, NJ, USA. ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00605826.

Disclosure

Howard Franklin and Andrew C Barrett are former employees of Salix. Ray Wolf is an employee of Valeant Pharmaceuticals. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BharuchaAEWaldAEnckPRaoSFunctional anorectal disordersGastroenterology200613051510151816678564

- DitahIDevakiPLumaHNPrevalence, trends, and risk factors for fecal incontinence in United States adults, 2005–2010Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol201412463664323906873

- BharuchaAEFecal incontinenceGastroenterology200312461672168512761725

- NelsonRFurnerSJesudasonVFecal incontinence in Wisconsin nursing homes: prevalence and associationsDis Colon Rectum19984110122612299788384

- MarklandADGoodePSBurgioKLIncidence and risk factors for fecal incontinence in black and white older adults: a population-based studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20105871341134620533967

- LeungFWSchnelleJFUrinary and fecal incontinence in nursing home residentsGastroenterol Clin North Am200837369770718794004

- TanJJChanMTjandraJJEvolving therapy for fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum200750111950196717874167

- BharuchaAEFletcherJGMeltonLJIIIZinsmeisterARObstetric trauma, pelvic floor injury and fecal incontinence: a population-based case-control studyAm J Gastroenterol2012107690291122415196

- XuXMeneesSBZochowskiMKFennerDEEconomic cost of fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum201255558659822513438

- ShahBJChokhavatiaSRoseSFecal incontinence in the elderly: FAQAm J Gastroenterol2012107111635164622964553

- Van KoughnettJAWexnerSDCurrent management of fecal incontinence: choosing amongst treatment options to optimize outcomesWorld J Gastroenterol201319489216923024409050

- MadoffRDParkerSCVarmaMGLowryACFaecal incontinence in adultsLancet2004364943462163215313364

- AltomareDFDeFMGiulianiRTCatalanoGCucciaFSphincteroplasty for fecal incontinence in the era of sacral nerve modulationWorld J Gastroenterol201016425267527121072888

- GalandiukSRothLAGreeneQJAnal incontinence-sphincter ani repair: indications, techniques, outcomeLangenbecks Arch Surg2009394342543318458939

- LehtoKHyotyMCollinPHuhtalaHAitolaPSeven-year follow-up after anterior sphincter reconstruction for faecal incontinenceInt J Colorectal Dis201328565365823440365

- ZutshiMTraceyTHBastJHalversonANaJTen-year outcome after anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum20095261089109419581851

- GlasgowSCLowryACLong-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic reviewDis Colon Rectum201255448249022426274

- BrownSRWadhawanHNelsonRLSurgery for faecal incontinence in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20137CD00175723821339

- MaedaYLaurbergSNortonCPerianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20132CD00795923450581

- DanielsonJKarlbomUSonessonACWesterTGrafWSubmucosal injection of stabilized nonanimal hyaluronic acid with dextranomer: a new treatment option for fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum20095261101110619581853

- DodiGJongenJde la PortillaFRavalMAltomareDFLehurPAAn open-label, noncomparative, multicenter study to evaluate efficacy and safety of NASHA/Dx gel as a bulking agent for the treatment of fecal incontinenceGastroenterol Res Pract2010201046713621234379

- SchwandnerOBrunnerMDietlOQuality of life and functional results of submucosal injection therapy using dextranomer hyaluronic acid for fecal incontinenceSurg Innov201118213013521245071

- La TorreFde la PortillaFLong-term efficacy of dextranomer in stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA/Dx) for treatment of faecal incontinenceColorectal Dis201315556957423374680

- DehliTStordahlAVattenLJSphincter training or anal injections of dextranomer for treatment of anal incontinence: a randomized trialScand J Gastroenterol201348330231023298304

- GrafWMellgrenAMatzelKEHullTJohanssonCBernsteinMEfficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trialLancet20113779770997100321420555

- TanENgoNTDarziAShenoudaMTekkisPPMeta-analysis: sacral nerve stimulation versus conservative therapy in the treatment of faecal incontinenceInt J Colorectal Dis201126327529421279370

- Fernández-FragaXAzpirozFApariciACasausMMalageladaJRPredictors of response to biofeedback treatment in anal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum20034691218122512972966

- StojkovicSGLimMBurkeDFinanPJSagarPMIntra-anal collagen injection for the treatment of faecal incontinenceBr J Surg200693121514151817048278

- FeretisMChapmanMThe role of anorectal investigations in predicting the outcome of biofeedback in the treatment of faecal incontinenceScand J Gastroenterol201348111265127124063579

- RockwoodTHChurchJMFleshmanJWFecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum200043191610813117

- UmscheidCAMargolisDJGrossmanCEKey concepts of clinical trials: a narrative reviewPostgrad Med2011123519420421904102

- AndromanakosNFilippouDSkandalakisPPapadopoulosVRizosSSimopoulosKAnorectal incontinence: pathogenesis and choice of treatmentJ Gastrointestin Liver Dis2006151414916680232

- WynneJMMylesJLJonesIDisturbed anal sphincter function following vaginal deliveryGut19963911201248881822

- SultanAHKammMAHudsonCNThomasJMBartramCIAnal-sphincter disruption during vaginal deliveryN Engl J Med199332926190519118247054

- HandaVLBlomquistJLKnoeppLRHoskeyKAMcDermottKCMunozAPelvic floor disorders 5–10 years after vaginal or cesarean childbirthObstet Gynecol2011118477778421897313

- StenbergALäckgrenGA new bioimplant for the endoscopic treatment of vesicoureteral reflux: experimental and short-term clinical resultsJ Urol19951542 Pt 28008037541869

- WatsonNFKoshyASagarPMAnal bulking agents for faecal incontinenceColorectal Dis201214Suppl 3293323136822

- Solesta® [package insert]Edison, NJOceana Therapeutics, Inc.2011

- BohleBBelvisFVialMMenopause and obstetric history as risk factors for fecal incontinence in womenDis Colon Rectum201154897598121730786

- MellgrenAPollackJMatzelKHullTBernsteinMGrafWLong-term efficacy of NASHA/Dx injection therapy (Solesta) for treatment of fecal incontinenceDis Colon Rectum201255535