Abstract

The burden of dementia in Japan is large and growing. With the world’s fastest aging population, it is estimated that one in five elderly people will be living with dementia in Japan by 2025. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), accounting for around two-thirds of dementia cases. A systematic review was conducted to examine the epidemiology and associated burden of AD in Japan and to identify how AD is diagnosed and managed in Japan. English and Japanese language databases were searched for articles published between January 2000 and November 2015. Relevant Japanese sources, clinical practice guideline registers, and reference lists were also searched. Systematic reviews and cohort and case–control studies were eligible for inclusion, with a total of 60 studies included. The most recent national survey conducted in six regions of Japan reported the mean prevalence of dementia in people aged ≥65 years to be 15.75% (95% CI: 12.4, 22.2%), which is much higher than the previous estimated rate of 10% in 2010. AD was confirmed as the predominant type of dementia, accounting for 65.8% of all cases. Advancing age and low education were the most consistently reported risk factors for AD dementia. Japanese guidelines for the management of dementia were released in 2010 providing specific guidance for AD about clinical signs, image findings, biochemical markers, and treatment approaches. Pharmacotherapies and non-pharmacotherapies to relieve cognitive symptoms were introduced, as were recommendations to achieve better patient care. No studies reporting treatment patterns were identified. Due to population aging and growing awareness of AD in Japan, health care expenditure and associated burden are expected to soar. This review highlights the importance of early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of AD as strategies to minimize the impact of AD on society in Japan.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly deteriorates the healthy brain, thereby affecting a person’s memory, thinking skills, emotions, behavior, and mood. Over time, a person’s ability to carry out daily activities becomes impaired. AD is the most common form of dementia, accounting for ~60%–80% of cases.Citation1 The 2015 World Alzheimer Report indicated there were 46.8 million people living with dementia worldwide, with the projected number of cases almost doubling every 20 years.Citation2 In Japan, a 2013 study commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) reported that more than 4.6 million Japanese were living with dementia.Citation3 This number is expected to reach 7 million in 2025, representing approximately one in five elderly people in Japan.Citation4

Patients who are memory impaired but have limited functional impairment and do not meet clinical criteria for dementia are classified as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI),Citation5–Citation7 or mild neurocognitive disorder as defined in the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V.Citation8 Increasingly, MCI is recognized as an important health care issue because of its association with significant morbidity, including the development of dementia and AD dementia.Citation9 MCI is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome, and new criteria for MCI due to AD are intended to help increase the accuracy of diagnosing AD in the pre-dementia stage.Citation7

In addition to cognitive impairments, more than 50% of patients with dementia experience behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), which include apathy, dysphoria (eg, depressive mood and sadness), euphoria, anxiety, irritability, social withdrawal, sundowning, sleep disorders, suspiciousness, disinhibition, disturbing behavior, delusions, hallucinations, stereotyped or repetitive behavior, and agitation or aggression.Citation10 BPSD are distressing for patients and their caregivers and are often the reason for admission of patients into residential care.Citation10,Citation11 Psychotropic medications have been extensively prescribed for the treatment of BPSD but are associated with increased mortality in patients. The death rate of elderly patients with dementia who were treated with atypical antipsychotic agents is estimated to be 1.6–1.7 times that of patients treated with placebo.Citation12 Additional comorbidities include pneumonia; cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and cardiac infarction; stroke; diabetes mellitus; and tumors.Citation13–Citation15 These concomitant diseases may play a role in increasing the mortality rate of dementia.

The specific aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of both the English and Japanese published literature on 1) the epidemiology of AD in Japan, including prevalence, incidence, conversion rate from MCI to dementia and/or AD dementia, comorbidity, mortality, and risk factors; 2) guidelines for treatment and real-world treatment patterns; and 3) the associated economic burden of AD in Japan, including direct and indirect costs, quality of life, and economic evaluations. The results of the first two reviews are presented here, with a follow-up report on the economic burden of AD in Japan to be published separately.

Materials and methods

Electronic searches of three English databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane library) and one Japanese database (ICHUSHI-WEB) were conducted in November 2015 for studies reporting on AD in Japan. The searches focused on the following: 1) epidemiology and 2) treatment guidelines and treatment patterns. EMBASE and MEDLINE searches were conducted via the OVID interface on November 11, 2015. The search strategies were modified and repeated in the Cochrane Library databases on November 17, 2015. The ICHUSHI-WEB database was searched on November 27, 2015. Each search comprised indexed keywords (subject headings) and free text terms appearing in titles and/or abstracts. Search terms included Alzheimer’s disease, treatment guidelines, treatment pattern, medication use, prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Details of each search strategy are provided in the Supplementary material.

Supplementary searches to identify any ongoing clinical trials, gray literature, or clinical practice guidelines were conducted using the following sources: University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR), World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), National Guidelines Clearing House, and Guidelines International Network. Reference lists of relevant articles identified for inclusion were also search for additional studies and reviews.

Records returned from each search were screened for eligibility using predefined reasons for exclusion. The main inclusion criteria included adults aged ≥18 years with AD in Japan. Articles were included if they were published in the English or Japanese language. Conference proceedings, books, and articles in press were eligible for inclusion, as were systematic reviews, prospective and retrospective population studies, and observational studies. Editorials, case reports, and general review articles were excluded. No date restrictions were applied to the search strategy; however, articles published prior to 2000 were not screened to avoid historical references to AD prevalence or treatment guidance provided prior to the approval of donepezil in Japan. The main exclusion criteria were as follows: non-human study, not a study of AD in adults, study that did not focus on Japanese population, or study that did not include at least one outcome relevant to this review, such as treatment patterns, guidelines for treatment, disease prevalence, incidence, morbidity, mortality, or factors influencing dementia or AD risk. Studies that enrolled fewer than 100 patients were excluded, as were studies with insufficient reporting of data. Relevant review articles were carefully screened to ensure that all primary studies were identified and that any duplicate citations were identified.

One systematic reviewer (SS) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified in the English databases to find citations that met the inclusion criteria and were relevant for full-text review. Quality checks to ensure whether inclusion criteria were appropriately applied were made by a second reviewer (MJ). Any disagreements regarding screening and study selection were resolved by consensus (SS, YC, MJ). The process for study selection was replicated for articles identified in the Japanese database by one independent reviewer (YC) with the exception that titles in Japanese were first screened in that language by an independent provider, and then abstracts identified for inclusion were translated into English and rescreened (YC) prior to full-text review.

After full-text review, relevant data were extracted into prespecified tables by one reviewer (SS) and checked by a second reviewer (YC). Quality appraisal of included studies was not conducted. Descriptive variables extracted for all included studies were author, year of publication, study design, and population characteristics (eg and age, disease severity). Additional variables extracted from epidemiology studies were prevalence, incidence, morbidity, mortality, and risk factors associated with dementia. Additional variables extracted from treatment guidelines were recommendations regarding diagnosis, pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions, and patient care. Studies reporting on mixed populations of dementia and AD were included, with the intention that data for AD be isolated from the broader population group. Attempts to derive information relating to the stages of AD (mild, moderate, and severe) were also to be made.

Results

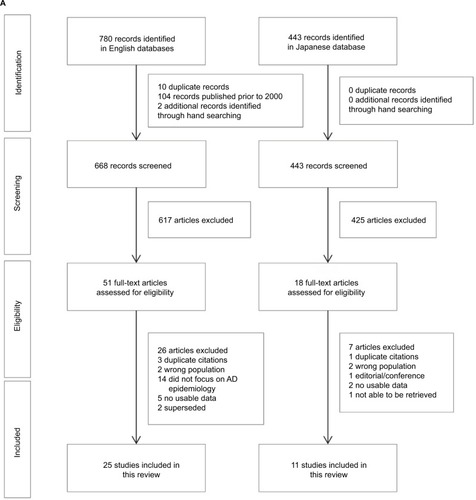

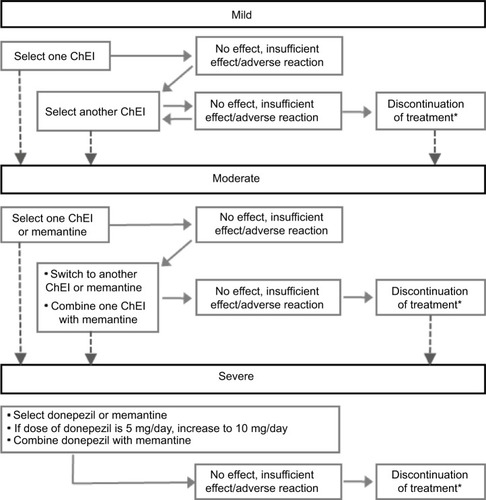

A PRISMA flowCitation16 presenting the results of the screening and selection process of articles identified in the English and Japanese databases is shown in . The combined English and Japanese language databases identified 1223 articles relating to prevalence, incidence, morbidity, mortality, and risk factors of AD in Japan. After removal of duplicates and studies published prior to 2000, 1111 citations were screened for inclusion, including two additional records identified through manual searching. Of these, 69 articles were identified as potentially relevant for inclusion, with 33 studies excluded after full-text review. A list of these studies, with reasons for exclusion, is presented in the Supplementary material. In total, there were 36 studies identified for inclusion that reported on the epidemiology of AD in Japan, including systematic reviews, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, and case–control studies.

Figure 1 Selection of studies relating to AD in Japan: (A) epidemiology and (B) treatment patterns and clinical practice guidelines.

From an initial 1567 citations relating to current clinical practice in Japan for the diagnosis and management of AD, 1525 citations were screened for suitability, including one article identified through manual searching. Of these, 43 articles were identified that potentially met the inclusion criteria, with 33 studies excluded after full-text review (Supplementary material). In total, 10 relevant papers relating to pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment of AD in Japan were identified. None of the identified studies provided information relating to real-world treatment patterns.

Epidemiology of AD in Japan

Prevalence

Studies that reported on dementia and/or AD prevalence across Japan are summarized in .Citation17–Citation21 Overall, the studies indicated the prevalence of all-cause dementia to be increasing in Japan, with a progressive rise in the prevalence of AD relative to vascular dementia (VaD) occurring. The evidence for a rise in AD is limited by variations in diagnostic criteria, changing age structures, and gender and regional variability.

Table 1 Reported prevalence of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease in Japan

A high-quality epidemiological survey on lifestyle-related diseases, ongoing since 1961 in Hisayama-cho, was identified to have conducted five prevalence studies of dementia (1985, 1992, 1998, 2005, and 2012) in all residents aged ≥65 years.Citation17,Citation22 The distribution of age, occupation, and nutrition intake of residents in Hisayama have remained at the mean level in Japan for the past 50 years and represent a typical Japanese sample population with few deviations. The prevalence studies were characterized by high accuracy, with high participation rates (92%–99%) and few dropouts from follow-up study (<1%), and included a morphological examination of the brain by cranial computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging and autopsy (80% of autopsy rate) for reevaluation of etiological dementia subtypes.Citation22

Based on the first four prevalence studies conducted in Hisayama between 1985 and 2005, Sekita et alCitation17 concluded that the prevalence of all-cause dementia and AD in the general Japanese population had significantly increased over the past two decades. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of all-cause dementia increased from 6.0% in 1985 to 8.3% in 2005 (p-trend=0.002) and was 1.34-fold higher in 2005 than in 1985 (p=0.08). This trend was observed in the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of all-cause dementia for both sexes but was only significant for women (p-trend=0.007). The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of AD increased from 1.1% in 1985 to 3.8% in 2005 (p-trend<0.001) and was 3.28-fold higher in 2005 than in 1985 (p<0.001). The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of VaD was reported to decrease from 2.3% in 1985 to 1.5% in 1998 and then increase to 2.5% in 2005. Thus, the ratio of VaD prevalence to that of AD prevalence decreased with time (2.1 in 1985, 1.2 in 1992, 0.7 in 1998, and 0.7 in 2005).

In 2012, the fifth cross-sectional Hisayama study was conducted, with the point prevalence of dementia continuing to rise from 7.1% in 1998 to 12.5% in 2005 and to 17.9% in 2012.Citation22 After adjustments for age and sex, this increasing trend was reported to remain (data not reported) and it was suggested that the prevalence of all-cause dementia has increased beyond the speed of aging. A significant increase in AD prevalence was also evident (about ninefold over 25 years), starting from 1.4% in 1985, increasing to 1.8% in 1992, 3.4% in 1998, 6.1% in 2005, and 12.3% in 2012. Conversely, the crude prevalence of VaD was largely unchanged over time, fluctuating at 2.4% in 1985, 1.9% in 1992, 1.7% in 1998, 3.3% in 2005, and 3.0% in 2012. Similar fluctuations were observed for the prevalence of dementia associated with other causes and unknown disease types (data not reported). The author suggested that only AD has consistently increased over time and that environmental factors may play a greater role than expected.

Consistent with the fifth cross-sectional Hisayama study, data from a 2012 national survey involving about 5000 people in six regions in Japan (Joetsu City, Niigata; Tone-machi, Ibaraki; Obu City, Aichi; Ama-cho, Shimane; Kitsuki City, Oita; and Imari City, Saga) indicated that the mean dementia prevalence rate in people aged ≥65 years was 15.75% (95% CI: 12.4, 22.2).Citation18 The survey also reported AD to be the most common form of dementia, accounting for 65.8% of cases, followed by VaD (17.9%), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)/Parkinson disease (4.1%), and frontotemporal dementia (0.9%). It was noted that the population aging rate was higher in all cities involved in the survey compared to the national average (22.5%) with the exception of Obu City in Aichi, thereby limiting the generalizability of dementia prevalence at the national level.

Two reviews were identified that suggested that large variations in dementia and AD prevalence could be attributed to differences in diagnostic criteria, epidemiological methods, mortality rate, and demographics associated with the aging population, but that overall, the prevalence of dementia, particularly AD, was on the rise in Japan.Citation19,Citation20 The review by Catindig et alCitation19 focused on the prevalence of dementia, AD and VaD in Asia and included six studies conducted in Japan. Dementia prevalence in Japan ranged from 4.2% (Nakayama region) to 33.2% (Hisayama region), and AD prevalence ranged from 0.9% (Hiroshima region) to 16% (Osaki-Tajiri region). The review by Dodge et alCitation20 examined changes in dementia prevalence and the relative prevalence of AD compared with VaD over time using eight large Japanese prevalence studies. After controlling for age and sex, the authors found that studies conducted in 1994, 1998, 2005, and 2008 had a higher prevalence of all-cause dementia when compared with the Okinawa 1991–1992 study. Likewise, the proportion of dementia cases attributed to AD was about 20% in 1985 increasing to around 60% over two decades.

One large population-based study was identified that focused on the prevalence of early onset dementia (EOD) in five catchment areas in Japan: Ibaraki, Gunma, Toyama, Ehime, and Kumamoto.Citation21 EOD was defined as dementia with an onset age <65 years old. A study, conducted between April 1, 2006, and December 31, 2007, estimated the standardized prevalence of EOD to be 47.6 per 100,000 (95% CI: 47.1, 48.1), a rate similar to that reported in Western countries (such as UK, USA, the Netherlands, and Finland). Unlike university-hospital-based studies that suggested that AD was the leading underlying cause of EOD in Japan, this community-based study showed that VaD was the most frequent cause of EOD (40.1%), followed by AD (24.3%), head trauma (8.4%), and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (3.6%).

Incidence

Three studies examining the incidence of dementia and/or AD in Japan were identified and are summarized in .Citation23–Citation25 Matsui et alCitation23 followed the 1985 prevalence cohort from the Hisayama study for 17 years, Yamada et alCitation24 followed the 1992–1996 prevalence cohort from the Hiroshima study for 5.9 years, and Meguro et alCitation25 followed a sub-sample of the 1998 Osaki-Tajiri study cohort for up to 7 years. Overall, these studies indicated a high risk for the development of dementia in the Japanese elderly population, with a greater incidence of AD compared with VaD being noted among those with a lower level of education.

Table 2 Reported incidence of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease in Japan

The Hisayama studyCitation23 prospectively followed a cohort of 828 subjects aged ≥65 years without dementia to determine the incidence of dementia and its subtypes. During the 17-year follow-up period, 275 subjects developed dementia corresponding to an incidence rate of 32.3 per 1000 person-years. The most frequent underlying type was AD (14.6 per 1000 person-years; n=124), followed by VaD (9.5; n=81), DLB (1.4; n=12), combined dementia (3.8; n=33), and other types of dementia (3.1, n=16). The incidences of AD, combined dementia, and other types of dementia increased with increasing age, particularly after the age of 85 years. This trend was not observed for VaD or DLB.

The Hiroshima studyCitation24 studied a cohort of 2286 dementia-free subjects aged ≥60 years. In 2003, 206 cases of dementia were newly diagnosed, with AD being the predominant underlying cause. The incidence of all-cause dementia per 1000 person-years was 12.0 for men and 16.6 for women. The incidence of AD per 1000 person-years was 5.6 for men and 11.3 for women. Poisson regression models showed that increasing age and lower education were statistically significant risk factors for development of dementia and probable AD, whereas an association with gender did not reach statistical significance.Citation26

The Osaki-Tajiri studyCitation25 investigated the incidence and associated risk factors for dementia in a community-based population aged over 65 years in northern Japan (Osaki-Tajiri). After a prevalence study in 1998, the dementia-free population were assessed in 2003 (5-year follow-up) and 2005 (7-year follow-up). The final participants included 204 (65.2%) healthy adults (Clinical Dementia Rating, CDR 0) and 335 (73.1%) people with questionable dementia (CDR 0.5). During the 5-year period, 3.9% (8/204) of the CDR 0 and 37.0% (20/54) of the CDR 0.5 participants developed dementia and during the 7-year period 40.2% (113/281) of the CDR 0.5 participants developed dementia. AD was the predominant type of dementia (42.9%), followed by AD with cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (17.9%), VaD (17.9%), and DLB (7.1%). No CDR 0 participants in the 65–69 years group developed dementia, whereas rising incidence rates were observed in older age groups.

Conversion from MCI to dementia or AD dementia

A 5-year longitudinal epidemiological study was identified that estimated the rate at which subjects with MCI progress to dementia in Nakayama, Japan.Citation27 Community dwellers aged 65 years were invited to participate over a 14-month period (January 1997–March 1998). The baseline sample comprised 104 subjects with MCI: 59 women and 45 men. During the 5-year follow-up period, eleven (10.6%) subjects were diagnosed with AD, five (4.8%) with VaD, and six (5.8%) with dementia of other etiologies. There were nine (8.7%) subjects who remained with a diagnosis of MCI and a further 40 (38.5%) subjects who returned to normal. Overall, the annual conversion rate from MCI to dementia was reported to be 16.1% per 100 person-years and the conversion rate from MCI to AD dementia was 8.5% per 100 person-years. This conversion rate was reported to be consistent with those described previously (7%–20% per year), with variations likely related to different measures used to define MCI across the studies.

Mortality and comorbidities in dementia

Several studies were found linking dementia with higher morbidity and mortality. The Hisayama studyCitation23 involving 828 people over a 17-year period reported the risk of death in dementia patients to be 1.7-fold higher than those without dementia. Here, median survival was 3.5 years in subjects with dementia compared with 5.8 years in those without dementia. The 10-year survival rate was 13.6% in dementia patients, which was significantly lower than 29.3% observed in the age- and sex-matched controls (hazard ratio: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.13; p<0.0001). In a 7-year survival studyCitation28 involving 272 patients, age, male gender, and hospitalization were reported to be significantly and independently related to an increased risk of mortality among dementia patients, while institutionalization was related to a decreased risk of mortality.

Data from MHLW show that cancer, heart disease, and stroke are the main causes of death in the general Japanese population, but respiratory failure or pneumonia is common in patients with AD and vascular diseases such as stroke and heart disease are commonly accompanied by VaD.Citation15 A retrospective cohort studyCitation13 involving 121 patients reported severity of dementia, male gender, presence of CVD, and use of neuroleptics to be significantly and independently associated with aspiration pneumonia in AD.

Also, a positive effect of treatment on life-time expectancy after onset of AD has been reported with the life-time expectancy in dementia patients receiving treatment with donepezil estimated to be 7.9 years compared with 5.3 years in the non-donepezil group.Citation29

Risk factors

A large body of literature on potential risk factors associated with dementia/AD in Japan was identified, many with the aim to identify effective interventions that may prevent the onset of AD. Much of the evidence comes from two large high-quality epidemiological studies,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation30–Citation40 with several prospective, retrospective, and case–control studies of lower quality also identified.Citation25,Citation41–Citation50 A summary of risk factors reported for dementia and/or AD dementia is presented in .

Table 3 Reported risk factors associated with Alzheimer’s disease in Japan

Advanced age and lower education were consistently recognized as risk factors for AD.Citation24–Citation26,Citation42 A significant association between APOE-ε4 and the onset of AD was also reported.Citation30,Citation31,Citation43,Citation44 The APOE is a protein related to fat metabolism and its risk can be modified according to the amount of fat intake.Citation51 The literature suggested other key factors associated with increased risk for AD including diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance; cardiovascular markers such as high levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and hypertension; biomarkers such as increased plasma interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 values at the agitation stage; and dietary and lifestyle factors such as low dairy and omega-3 fatty acid consumption, high alcohol consumption, long-term smoking, and physical inactivity.

One reviewCitation49 suggested that the rising prevalence of AD in Japan was related to the transition from a traditional diet, which is predominantly high in vegetable and grains, to a Western diet, which is more focused on meat and dairy.

Diagnosis and treatment of AD in Japan

In 2010, clinical practice guidelines for the management of dementing diseases were developed by six major societies in Japan including the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology, the Japan Society for Dementia Research, the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, the Japan Geriatrics Society, the Japanese Society of Neurological Therapeutics, and the Japanese Society of Neurology, which outlined clinical signs, image findings, biochemical markers, and pharmacologic treatment guidance for AD.Citation11,Citation52 The 2010 guidelines also introduced non-pharmacologic therapies to relieve cognitive symptoms and provided recommendations for patient care. The 2010 guidelines and practical strategies identified in the literature are largely in line with the US Alzheimer’s Disease Management Council (ADMC) consensus for the management of AD.Citation53

Diagnosis

The 2010 guidelines recommended diagnosis of AD be based on psychiatric and neurological signs, imaging findings, and the presence of biomarkers, as summarized in . A pattern of cognitive impairment characterized by recent memory impairment and delayed recall of memory tasks was noted as a particularly useful method of discrimination from a healthy person or from other dementing diseases. In the case of early onset of AD, impairments other than the memory, such as aphasia, visuospatial cognition impairment, and visual constructional impairment, also often occur as the precursory symptoms. As AD progresses, disorientation and parietal lobe symptoms such as visuospatial impairment and constructional apraxia may be observed with a decline of insight into disease, psychiatric symptoms such as depression and apathy, and characteristic social behaviors such as “lie-to-cover-up” and “pretend-to-understand” reactions.Citation11,Citation52 In some cases, theft paranoia can be seen from a relatively early stage but significant focal neurological symptoms are rarely observed in the early stages of the disease.

Table 4 Diagnosis of AD in Japan as recommended by 2010 guidelines

In Japan, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is widely used for the diagnosis and clarification of dementia. SPECT can provide high specificity for AD against other types of dementia and can recognize diagnostic patterns in AD.Citation11,Citation52

Pharmacotherapy

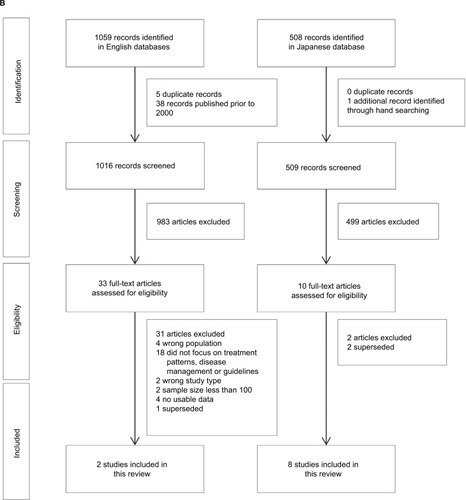

At the release of the 2010 guidelines,11 the cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI) donepezil was the sole medication approved in Japan and indicated for AD dementia. Recommendation for other ChEIs (eg, galantamine and rivastigmine) and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist (memantine) were made based on meta-analyses of safety and efficacy of each drug. In 2012, subsequent to the approval of galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, a compact version of the 2010 guidelines enclosed a treatment algorithm to inform the selection of therapeutic drugs based on disease progression,Citation54 as summarized in .

Figure 2 Treatment algorithm for the management of AD in Japan.

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ChEIs, cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine).

Given that the 2010 guidelines were released before the availability of these new medications, further guidance in drug selection, dose regimen, and drug switching in clinical practice has been provided, with several reviews and personal opinions on the practical treatment strategy for the management of AD identified in the systematic literature review.Citation55–Citation59

Most reviews focused on disease severity and patient characteristics as being the primary influence for drug selection.Citation55–Citation58 One authorCitation55 suggested that pharmacological properties of the drugs should also be taken into account, such as mechanism of action, half-life, and safety profile. From a caregiver’s point of view, another authorCitation57 suggested that galantamine was more effective than other drugs when administered in medium- and long term, resulting in a delay in admission to nursing home. A third authorCitation58 outlined a dose adjustment schedule based on the 2010 guidelines that suggested that drug doses should be started at a lower than recommended dose and then increased gradually to avoid adverse drug reactions.

Based on disease severity, ChEIs were recommended as the first-choice medicine. Donepezil was often mentioned as the first choice of medicine for mild AD dementia, as it is considered safe and efficacious even in patients aged >85 years;Citation56,Citation60 however, rivastigmine was also mentioned for use in patients with early symptoms of AD.Citation56 Both ChEIs and memantine were recommended for moderate AD dementia, with the combination of ChEIs and memantine also as an option for both moderate and severe AD dementia, particularly among those who have trouble with daily living.Citation56,Citation59 Among AD patients with CVD or with BPSD, both galantamine and memantine were recommended.Citation54,Citation56

Non-pharmacotherapy

A number of non-pharmacotherapies for AD were mentioned in the guidelines as a means of managing or improving patient symptoms.Citation11 For all therapies, it was noted that the strength of the evidence was weak due to lack of blinding and difficulty in efficacy measurement (Grade C1). A summary of non-pharmacotherapies used in the management of AD in Japan is provided in .

Table 5 Non-pharmacotherapies for AD assessed in the 2010 guidelinesTable Footnotea

Patient and caregiver care

The 2010 guidelines noted that no patient care programs specific for AD are established in Japan. General dementia care is applied, which includes caregiver education and stress management (Grade B) and patient-oriented care and validation therapy (Grade C1).

To reduce burden on the family and to relieve stress and depression caused by long-term care of AD patients, the guidelines highlighted the importance of providing caregivers access to stress management, support groups, and care resources that may include counseling, kinesitherapy, workshops, helpers, day service, and short stays for the family. Also, although there is no evidence indicating the efficacy, validity, or reliability of patient-oriented care, the guidelines recommend that patient-oriented care should be introduced from a humanitarian and ethical point of view, as it is essential to the establishment of self-respect in the advanced stage of AD patients. Patient-oriented care puts quality of person in the center of care in contrast to conventional care where medical correspondence is at the core. Validation therapy is an approach of dementia care similar to patient-oriented care, focusing on acceptance and sympathy.

General principles regarding the attitude of caregivers to patient care were introduced in the 2010 guidelinesCitation11 and were based on those recommended by the American Psychiatric Association. The recommendations were as follows: understand that the condition will involve a decline in the patient’s ability and not to have high expectations; be careful about the rapid progress and appearance of a new symptom; try simple instructions and demands, and when the patient is confused or angry, change the demand; avoid difficult work that may lead to a failure; do not force the patient to face their impairment; try to behave in a calm, stable, and supportive manner; avoid an unnecessary change; and explain things in as detailed a way as possible, giving hints to keep the patient orientated.

Alzheimer drugs in clinical practice

Based on published reviews and personal opinions, treatment initiation for dementia, MCI, or AD dementia is recommended to be initiated as early as possible,Citation56,Citation59 with treatment efficacy to be evaluated every 2–3 months. Switching medications is to be considered only when no response is observed following ~6 months of treatment and switching to a new drug that is indicated for the same disease severityCitation56 and to be administered immediately.Citation58 If the previous ChEI is discontinued due to adverse events (AEs), it is recommended that the new ChEI is administered after confirmation that the patients is free from the AEs.Citation58 Pharmacotherapy should be continued until either intolerance to AEs or when the disease progresses to the terminal stage (ie, unable to take food due to dysphagia or requiring nursing care).Citation56,Citation58

It should be noted that the majority of pharmacotherapies recommended for the treatment of AD dementia (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine) act by treating AD symptoms. Disease-modifying therapies that target the underlying etiologies of the disease are still under development. Patients treated with the four currently licensed drugs will eventually experience deterioration of their symptoms due to the natural progression of the disease process. Therefore, drug treatments for cognitive symptoms, controlling of BPSD, non-pharmacological intervention, and care programs to improve the quality of life for both patients and caregivers are of equal importance.

There were no studies identified in the systematic literature review that reported on treatment or prescribing patterns in the management of cognitive function among patients with AD dementia in Japan. However, one claims database analysis was located that examined trends in the use of psychotropic medications for tackling severe agitation, aggression, and psychosis associated with BPSD in Japanese patients.Citation61 The study utilized data from a 2002–2010 survey of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of claims data for the month of June in every year. Data from 15,591 patients with dementia aged ≥65 years who were prescribed ChEIs at ambulatory care visits revealed, in 2008–2010, that the most frequently prescribed psychotropic medications were sedative-hypnotics (37.5%), antipsychotics (24.9%), antidepressants (13.0%), and mood-stabilizers (2.9%). Between 2002–2004 and 2008– 2010, use of second-generation antipsychotics increased from 5.0% to 12.0%, while use of first-generation antipsychotics decreased from 20.6% to 12.9%. The results suggested a slight increase in the off-label use of antipsychotics over time.

Discussion

This systematic literature review provides a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology and recommended clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of AD in Japan and reveals a paucity of evidence relating to real-world treatment patterns for this disease in Japan. With life expectancy in Japan among the highest in the world, AD will increasingly become a significant health care problem. This is because disability associated with dementia, and the resources needed to care for patients with AD, increases with age. Indeed, the social burden associated with dementia in Japan is reported to have increased 2.2 times from ¥755.9 billion in 2002 to ¥1,653.4 billion in 2011.Citation62

Several studies were identified that demonstrate the prevalence of dementia to be increasing in Japan, driven by population aging, growing awareness of AD, and a variety of other potential risk factors.14,17–21,23,24,27,57 These findings are in contrast to that reported in the USA, where the prevalence and incidence of dementia have been stable or declining, and the risk of AD is presumed to remain constant.Citation63,Citation64 A key contributor to the rise in overall dementia in Japan is the steady increase in AD prevalence, with AD taking over from VaD as the most commonly cited cause of dementia. In the Hisayama study, AD prevalence among those aged ≥65 years increased from 1.4% in 1985 to around 12.3% in 2012; correlating with an increase in overall dementia from 6.7% in 1985 to 17.9% in 2012.Citation20,Citation22

Trends in incidence of dementia in Japan illustrate older age and female gender to be associated with AD more than VaD, with reasons for growth in AD beyond the speed of aging or protective factors for dementia continuing to be explored.Citation23–Citation26 Several studies showed education level, presence of diabetes, transition to a more Western diet, and lifestyle factors such as high alcohol intake and low physical activity to be associated with an increased risk of AD in Japan.Citation22,Citation25,Citation32–Citation34,Citation49,Citation50 Many of these risk factors correlate with those identified elsewhere, where changes in education and socioeconomic status, a decline in CVD, and an increasing prevalence of hypertension and diabetes have been offered as possible explanations for influencing the development of dementia in North America, the UK, and Europe.Citation64–Citation71

The identification of numerous risk factors for AD in Japan provides multiple pathways to potentially target to prevent or reduce the risk of developing AD dementia in later age. Public health interventions directed at improving diet and the level of physical activity and continued focus on identifying and managing cardiovascular and CVD are some examples that may provide benefit by slowing the development of AD. Continuous research to strengthen the evidence to ascertain causality and to identify genetic risk factors for AD is also needed.

Early detection and early treatment are considered highly important in the management of AD and dementia.Citation11,Citation52 The current diagnosis of AD relies on the presence of cognitive impairment and ruling out of other diseases. Patients who do not meet the clinical criteria for dementia or AD dementia may be classified as having MCI; however, the diagnosis of MCI does not necessarily predict the development of dementia or AD dementia.Citation27 The development of more reliable tests to improve confidence in AD diagnosis, including improvements in biomarker tests to detect Aβ, would allow for initiation of early intervention and improved patient outcomes and quality of life.Citation72

The current focus of research for many AD treatments is to delay the development of the disease. Indeed, if interventions could either delay the onset of dementia or disease progression by one or two years, it is projected that the global burden of this disease would be significantly reduced, with more than 20% fewer cases of AD occurring in 2050.Citation73 The ChEIs (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and NMDA receptor antagonists (memantine) are currently approved in Japan and indicated for AD dementia. Of note, these pharmacotherapies treat the symptoms of AD but have not been shown to prevent the progression of AD itself. Therefore, non-pharmacological interventions and patient care programs focused on controlling behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia play an important role in improving quality of life for patients and their caregivers. Disease-modifying therapies that target the underlying etiologies of the disease are still in development.

Clinical guidelines for the management of dementia were released in 2010 providing general treatment guidance for AD. A revised version of the guidelines was published in August 2017, which updated the chapters on diagnosis, pharmacotherapy, non-pharmacotherapy, and patient and caregiver care.Citation74 Diagnosis of AD cited upgraded diagnostic criteria and the usage of amyloid PET. There was no significant change in the treatment algorithm for AD, but recent evidence from RCTs, systematic literature reviews, and meta-analysis were added on the anti-AD medications. This systematic review identified a paucity of data on the real-world clinical practice pattern of AD in Japan. Claims database analyses are warranted to provide a treatment pattern and the market uptake of those anti-AD medications.

Our study has limitations, with the focus being on the qualitative synthesis of English and Japanese literature. Due to the nature of the evidence, no meta-analyses or publication tests such as a funnel plot analysis were conducted. Also, there is an assumption that Japanese articles were correctly identified and translated into the English language. Our review is, therefore, potentially subject to publication bias and selective reporting within studies.

Conclusion

With the world’s fastest aging population, the burden of AD in Japan is growing. Strategies to improve diagnosis, treatment, and manage risk factors have the potential to reduce the overall burden on families, caregivers, and the health care system. New interventions that slow disease progression or delay disease onset would have a major impact on reducing the burden of this disease on the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wei Du from TransPerfect for assistance with translations of Japanese language articles. This review was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure

William Montgomery, Tomomi Nakamura, and Kaname Ueda are all employees at Eli Lilly and Company. Margaret Jorgensen, Shari Stathis, and Yuanyuan Cheng are employed by Health Technology Analysts Pty Ltd, which was commissioned by Eli Lilly and Company to undertake this review of Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figuresAlzheimers Dement201612445950927570871

- Alzheimers Disease InternationalImproving healthcare for people living with dementia: Coverage, quality and costs now and in the futureWorld Alzheimer Report 2016: The Global Voice on Dementia2016 Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016Accessed May 11, 2017

- Kyodo Staff ReportJapan grapples with ¥14.5 trillion dementia costsThe Japan Times5292015National, Science and Health Available from: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/05/29/national/science-health/japan-grapples-with-%C2%A514-5-trillion-dementia-costs/#.WDy8o0YyaaoAccessed June 25, 2016

- Kyodo Staff ReportNumber of dementia patients to reach around 7 million in Japan in 2025The Japan Times182015National, Science and Health http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/01/08/national/number-dementia-patients-reach-around-7-million-japan-2025/#.WDzC4EYyaaoAccessed June 25, 2016

- PetersenRCMild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entityJ Intern Med2004256318319415324362

- GauthierSReisbergBZaudigMMild cognitive impairmentLancet200636795181262127016631882

- AlbertMSDeKoskySTDicksonDThe diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement20117327027921514249

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- BozokiAGiordaniBHeidebrinkJBerentSFosterNMild cognitive impairments predict dementia in nondemented elderly patients with memory lossArch Neurol20015841141611255444

- HerschECFalzgrafSManagement of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementiaClin Interv Aging20072461162118225462

- Japanese Society of NeurologyChapter V: Alzheimer’s diseaseDementia Disease Treatment Guidelines2010 Available from: https://www.neurology-jp.org/guidelinem/nintisyo.htmlAccessed December 24, 2015 Japanese

- AlertFDAInformation for healthcare professionals: conventional antipsychotics2008 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htmAccessed May 10, 2016

- WadaHNakajohKSuzukiTOhruiTRisk factors of aspiration pneumonia in Alzheimer’s disease patientsGerontology20014727127611490146

- MeguroKIshiiHYamaguchiSPrevalence of dementia and dementing diseases in Japan: the Tajiri projectArch Neurol20025971109111412117358

- Ministry of Health Labour and WelfareStatistics of annual population census2010 Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/suikei10/index.htmlAccessed May 5, 2016

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGGroupPPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementJ Clin Epidemiol200962101006101219631508

- SekitaANinomiyaTTanizakiYTrends in prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in a Japanese community: the Hisayama StudyActa Psychiatr Scand2010122431932520626720

- AsadaT[Prevalence of dementia in Japan: past, present and future]Rinsho Shinkeigaku20125211962964 Japanese23196483

- CatindigJAVenketasubramanianNIkramMKChenCEpidemiology of dementia in Asia: insights on prevalence, trends and novel risk factorsJ Neurol Sci201232112111622857988

- DodgeHHBuracchioTJFisherGGTrends in the prevalence of dementia in JapanInt J Alzheimers Dis2012201295635423091769

- IkejimaCIkedaMHashimotoMMulticenter population-based study on the prevalence of early onset dementia in Japan: vascular dementia as its prominent causePsychiatry Clin Neurosci201468321622424372910

- KiyoharaY[Life science to support preemptive medicine: environmental determinants of Alzheimer’s disease]Exp Med201533710321037 Japanese

- MatsuiYTanizakiYArimaHIncidence and survival of dementia in a general population of Japanese elderly: the Hisayama studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200980436637018977814

- YamadaMMimoriYKasagiFIncidence of dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia in a Japanese population: Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health StudyNeuroepidemiology200830315216018382114

- MeguroKIshiiHKasuyaMIncidence of dementia and associated risk factors in Japan: the Osaki-Tajiri ProjectJ Neurol Sci20072601217518217507030

- YamadaMMimoriYKasagiFMiyachiTOhshitaTSasakiHIncidence and risks of dementia in Japanese women: Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health StudyJ Neurol Sci200928312576119394050

- IshikawaTIkedaMMild cognitive impairment in a population-based epidemiological studyPsychogeriatrics20077104108

- NohtomiATsukamotoSPredictors of mortality in patients with dementia: a seven-year survival studyPsychogeriatrics200441A37

- MeguroKKasaiMAkanumaKMeguroMIshiiHYamaguchiSDonepezil and life expectancy in Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective analysis in the Tajiri ProjectBMC Neurol20141483

- OharaTNinomiyaTKuboMApolipoprotein genotype for prediction of Alzheimer’s disease in older Japanese: the Hisayama studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20115961074107921649613

- IwakiTGlucose tolerance disorder as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Clin Experiment Med20122428604605 Japanese

- OharaT[Glucose tolerance status and risk of dementia in the community: the Hisayama study]Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi: Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica201311519097 Japanese23691800

- OzawaMNinomiyaTOharaTDietary patterns and risk of dementia in an elderly Japanese population: the Hisayama studyAm J Clinic Nutrit201397510761082

- OzawaMOharaTNinomiyaTMilk and dairy consumption and risk of dementia in an elderly Japanese population: the Hisayama studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20146271224123024916840

- KiyoharaY[Background factors and risk factors for dementia as seen from the Hisayama-machi study]Biomed Therap2008426635638 Japanese

- KiyoharaY[Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease]Bio Clinica2009243280284 Japanese

- KiyoharaY[Dementia up to date: epidemiology of dementia – based on Hisayama study]Mol Cerebrovasc Med201092147153 Japanese

- KiyoharaY[Cognitive function and hypertension: epidemiology of dementia – Hisayama study]Blood Pressure2012198684688 Japanese

- NinomiyaTOharaTHirakawaYMidlife and late-life blood pressure and dementia in japanese elderly: the Hisayama studyHypertension2011581222821555680

- YamadaMKasagiFSasakiHMasunariNMimoriYSuzukiGAssociation between dementia and midlife risk factors: the Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc200351341041412588587

- HonmaTHattaKHitomiYIncreased systemic inflammatory interleukin-1s and interleukin-6 during agitation as predictors of Alzheimer’s diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201328323324122535710

- SakuraiHHanyuHSatoTVascular risk factors and progression in Alzheimer’s diseaseGeriatr Gerontol Int201111221121421143566

- FujiwaraYTakahashiMTanakaMHoshiTSomeyaTShinkaiSRelationships between plasma beta-amyloid peptide 1–42 and athero-sclerotic risk factors in community-based older populationsGerontology200349637437914624066

- UrakamiKWakutaniYNakajimaKPathogenetic mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease – epidemiology and risk factors of dementiaJpn J Neuropsychopharmacol2001216222 Japanese

- ShibataNOhnumaTBabaHAraiHGenetic association analysis between TDP-43 polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease in a Japanese populationDement Geriatr Cogn Dis2009284325329

- TsutsumiANishiguchiMKikuyamaHHoukyouAKohIYonedaHTumor necrosis factor-alpha-863A/C polymorphism is associated with Alzheimer’s diseasePsychiatry Clin Neurosci2007612S16

- WatanabeTMiyazakiAKatagiriTYamamotoHIdeiTIguchiTRelationship between serum insulin-like growth factor-1 levels and Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementiaJ Am Geriatr Soc200553101748175316181175

- TanahashiHAsadaTTabiraTAssociation between Tau polymorphism and male early-onset Alzheimer’s diseaseNeuroReport200415117517915106853

- GrantWBTrends in diet and Alzheimer’s disease during the nutrition transition in Japan and developing countriesJ Alzheimers Dis201438361162024037034

- AsadaTPrevention of Alzheimer’s disease: putative nutritive factorsPsychogeriatrics200773125131

- LiuCCLiuCCKanekiyoTXuHBuGApolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapyNat Rev Neurol20139210611823296339

- TokudaT[Disease review: diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease]SRL Hokan Quarterly20133341929 Japanese

- MuramatsuKYoshizakiTTherapeutic drug selection for Alzheimer’s disease treatmentShinryo [Diagnosis and Treatment]20151037889894 Japanese

- Japanese Society of NeurologyChapter V: Alzheimer’s diseaseDementia disease treatment guidelines 2010: Compact Edition2012 Available from: https://www.neurology-jp.org/guidelinem/nintisyo_compact.htmlAccessed May 10, 2016

- AraiHPractical strategy of pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease – from the clinical point of viewCogn Dement201110Suppl 13539 Japanese

- EndoH[Selection criteria of drugs for Alzheimer’s disease treatment]J New Remed Clinics2013621101103 Japanese

- EndoHMiuraHSatakeSNew development of therapuetic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease – the merit of drugs for care giver of Alzheimer’s diseaseCogn Dement201110Suppl 15558 Japanese

- NakamuraYNew era of drugs for Alzheimer-type dementia: practical strategy for four antidementia drugs and classification of disease severity of dementiaMedicinal2012258288 Japanese

- MoritaKShojiYFujikiRHiroyukiYMasayukiITherapeutic strategy for Alzheimer-type dementiaJpn J Clin and Experiment Med2014911216411646 Japanese

- AraiHCurrent therapies in dementiaNihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi200441310313 Japanese15237749

- OkumuraYTogoTFujitaJTrends in use of psychotropic medications among patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors in Japan from 2002 to 2010Int Psychogeriatr201527340741525213318

- HanaokaOMatsumotoKKitazawaTSetoKFujitaSHasegawaTSocial burden associated with dementia in JapanJ Jpn Soc Healthcare Manage20152-K-3216 (Suppl)280 Japanese

- BrookmeyerRGraySKawasCProjections of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onsetAm J Public Health1998889133713429736873

- RoccaWAPetersenRCKnopmanDSTrends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United StatesAlzheimers Dement201171809321255746

- OttAStolkRPvan HarskampFPolsHAHofmanABretelerMMDiabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: the Rotterdam studyNeurology19995391937194210599761

- OttAvan RossumCTvan HarskampFvan de MheenHHofmanABretelerMMEducation and the incidence of dementia in a large population-based study: the Rotterdam StudyNeurology199952366366610025813

- SternYCognitive reserve and Alzheimer diseaseAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord200620211211716772747

- GamaldoAMoghekarAKiladaSResnickSMZondermanABO’BrienREffect of a clinical stroke on the risk of dementia in a prospective cohortNeurology20066781363136917060561

- IvanCSeshadriSBeiserADementia after stroke: the Framing-ham StudyStroke20043561264126815118167

- FratiglioniLPaillard-BorgSWinbladBAn active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementiaLancet Neurol20043634335315157849

- QiuXu WLWahlinCXWinbladAFratiglioniBLDiabetes mellitus and risk of dementia in the Kungsholmen project: a 6-year follow-up studyNeurology20046371181118615477535

- HornbergerJBaeJWatsonIJohnstonJHappichMClinical and cost implications of amyloid beta detection with amyloid beta positron emission tomography imaging in early Alzheimer’s disease – the case of florbetapirCurr Med Res Opin201733467568528035842

- BrookmeyerRJohnsonEZiegler-GrahamKArrighiHMForecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement20073318619119595937

- Japanese Society of NeurologyChapter 6: Alzheimer’s diseaseDementia Disease Treatment Guidelines 2017: Igaku-shoin Japanese. Available from: https://www.neurology-jp.org/guidelinem/index.htmlAccessed October 10, 2017

- McKhannGDrachmanDFolsteinMKatzmanRPriceDStadlanEMClinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s DiseaseNeurology19843479399446610841

- RomanGCTatemichiTKErkinjunttiTVascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International WorkshopNeurology19934322502608094895

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed text revWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000