Abstract

Background:

The vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab (BEV) given in combination with interferon-α-2a (IFN), and the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sunitinib (SUN) and pazopanib (PAZ), have all shown significant increase in progression-free survival (PFS) in first-line metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (mRCC) therapy. These targeted therapies are currently competing to be primary choice; hence, in the absence of direct head-to-head comparison, there is a need for valid indirect comparison assessment.

Methods:

Standard indirect comparison methods were applied to independent review PFS data of the pivotal Phase III trials, to determine indirect treatment comparison hazard-ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). As BEV+IFN and SUN have been compared to IFN, indirect comparison was enabled by the common IFN comparator arms. As PAZ was compared to placebo (PLA), a connector trial (IFN vs PLA) was required for the indirect comparison to BEV+IFN. Sensitivity analyses taking into account real-life influence of patient compliance on clinical outcomes were performed.

Results:

The indirect efficacy comparison resulted in a statistically nonsignificant PFS difference of BEV+IFN vs SUN (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.78–1.45; P = 0.73) and of BEV+IFN vs PAZ (range based on different connector trials; HR: 0.74–1.03; P = 0.34–0.92). Simulating real-life patient compliance and its effectiveness impact showed an increased tendency towards BEV+IFN without reaching statistical significance.

Conclusions:

There is no statistically significant PFS difference between BEV+IFN and TKIs in first-line mRCC. These findings imply that additional treatment decision criteria such as tolerability and therapy sequencing need to be considered to guide treatment decisions.

Introduction

Metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (mRCC) has always been one of the most drug-resistant malignanciesCitation1 and the 5-year survival rates remain low at only around 10% and had not improved by 2008.Citation2,Citation3

Over the past two decades, immunomodulating drugs such as interferon-α-2a (IFN) have been the standard first-line mRCC treatment,Citation4 and have been considered the standard comparator in clinical trials.Citation5 Recent advances in understanding the molecular biology of kidney cancer have resulted in the development of drugs that target known molecular pathways which are believed to be important in this disease, such as vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors.

The vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab (BEV) given in combination with IFN, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sunitinib (SUN) and pazopanib (PAZ), have all shown significant increase in progression-free survival (PFS) in first-line mRCC therapy. These targeted therapies are currently competing to be the primary choice for the first-line therapy of mRCC patients presenting a good or intermediate prognosis. Hence, in the absence of direct head-to-head comparison, there is a need for valid indirect comparison assessment.

Material and methods

Pivotal trial outcomes

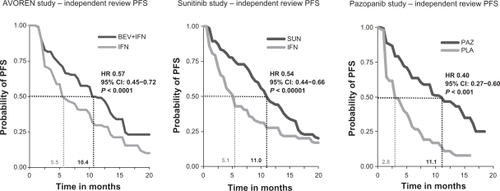

The published Phase III pivotal trial PFS outcomes have been selected as the basis of the indirect treatment comparison (ITC), as these present the highest quality data based on independent central review assessment. Within these pivotal trials BEV+IFNCitation6 and SUNCitation7 have each shown a significant increase in PFS vs IFN in first-line mRCC therapy, whereas PAZ has shown a significant PFS increase compared to placebo (PLA),Citation8 as shown in .

Figure 1 Pivotal Phase III progression-free survival outcomes in first-line mRCC therapy.

Abbreviations: AVOREN, AVastin fOr RENal cell cancer; BEV, bevacizumab; CI, confidence intervals; IFN, interferon-α-2a; HR, hazard ratio; PAZ, pazopanib; PFS, progression-free survival; PLA, placebo; SUN, sunitinib.

The PFS hazard ratios (HRs) were selected as the preferred outcome for the ITC, as this effect measure accounts for censoring and incorporates time to event information.Citation9

The independent review PFS HR of BEV+IFN vs IFN is 0.57 (95% confidence intervals [95% CI]: 0.45–0.72; P < 0.0001),Citation6 the PFS HR of SUN vs IFN is 0.54 (95% CI: 0.44–0.66; P < 0.00001)Citation7 and the PFS HR of PAZ vs PLA is 0.40 (95% CI: 0.27–0.60; P < 0.001),Citation8 respectively.

The BEV+IFN study named AVOREN and the SUN trial focused on treatment-naïve mRCC patients (first-line population), whereas the PAZ study included both treatment-naïve and pretreated mRCC patients. Hence for the ITC the pazopanib results of treatment-naïve patients have been applied, based on prespecified subgroup analysis.

As shown in study designs, patient characteristics, enrolment criteria, and study measurements are comparable, but not identical, between the AVOREN trial, the SUN trial, and the PAZ study.

Table 1 Comparison of the main study design, patient characteristics, enrolment criteria, and study measurements of the underlying pivotal trials

AVOREN and the PAZ trial were double-blinded placebo-controlled randomized trials, whereas the SUN study was a randomized open-label study. Furthermore, within the AVOREN trial 100% of patients were neph-rectomized (inclusion criteria) whereas in the SUN and the PAZ trial 88%–91% of patients had a previous nephrectomy. Another difference is that the SUN and the PAZ trials included more patients with a favorable prognosis (MSKCC risk score 0: 34%–39%) compared to the AVOREN study (27%–29%). Although both factors are regarded as predictive for the PFS outcome, the between-study differences are small, hence performing an indirect treatment comparison (ITC), without applying adjustments for patient characteristics variations, was regarded as an appropriate approach.

Indirect treatment comparison approach

The indirect treatment comparison of PFS outcomes of BEV+IFN vs SUN and vs PAZ uses the most widely applied indirect comparison approach by Bucher et al.Citation12 The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in HealthCitation13 and othersCitation14,Citation15 have recently identified this method as the most suitable approach for performing indirect treatment comparisons of randomized controlled trials.

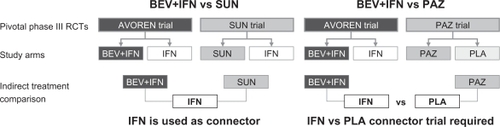

As BEV+IFN and SUN have been compared to IFN, indirect comparison was enabled by the common IFN control arms, whereas for comparing BEV+IFN vs PAZ a connector trial (IFN vs PLA) is required, as shown in .

Figure 2 Indirect treatment comparison: efficacy connections between the pivotal trials.

For the identification of suitable connector trials a systematic literature search was performed using the following literature databases: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. As a result only three IFN studies have been identified that provided a suitable PFS HR compared to the Phase III trial outcomes (median PFS of IFN ≈ 5 months and median PFS for PLA ≈ 3 months) in treatment-naïve mRCC patients. Although none of these compared IFN vs PLA, the selected studies compared IFN regimens either to placebo-like therapy (MRCRCC trialCitation16) or to other IFN regimens that had a placebo-like PFS outcome (Aass et alCitation17 and Mickisch et alCitation18). In the absence of a valid IFN vs PLA connector trial all of these studies have been used to perform the ITC of BEV+IFN vs PAZ. Furthermore a PFS HR was estimated (‘proxy comparison’) based on the median PFS time of IFN (5.4 monthsCitation6) and of placebo (2.8 monthsCitation8) by assuming constant hazards (HR IFN vs PLA = 2.8 m/5.4 m = 0.52). The selected connector trials and the PFS HRs applied for IFN vs PLA are shown in .

Table 2 Overview of selected connector trials

The indirect comparisons of BEV+IFN vs SUN and BEV+IFN vs PAZ were performed for two key scenarios:

Indirect efficacy comparison: comparison of the Phase III results as published.

Indirect effectiveness assessment based on simulating the impact of patient compliance.

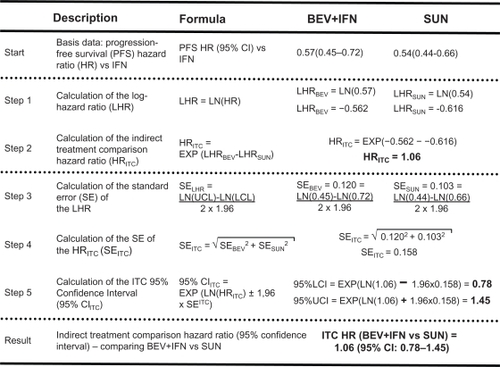

For both scenarios the indirect comparison HR of BEV+IFN vs TKIs with 95% CIs are provided. shows the detailed calculation pathway defined by Bucher et al,Citation12 including the BEV+IFN vs SUN comparison.

Figure 3 Indirect comparison methodology according to Bucher et alCitation12 showing the calculations for the comparison of BEV+IFN vs SUN.

Abbreviations: BEV, bevacizumab; IFN, interferon-α-2a; ITC, indirect treatment comparison; SUN, sunitinib.

For the comparison of BEV+IFN vs PAZ the same methodology was applied, but two ITCs needed to be performed in contrast to the SUN comparison. In a first step, the ITC HR of PAZ vs IFN was calculated (using the published PAZ PFS HR and the connector trials’ PFS HR) and in a second step this ITC HR result was compared to the published PFS HR of BEV+IFN.

All calculations have been performed in Excel 2003 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The ITC calculations can be reperformed using the ITC toolCitation20 available from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, which ensures maximum transparency.

Patient compliance

As the TKIs, SUN and PAZ are oral medications that are self-administered by the patient and show a considerable adverse event profileCitation7,Citation8, compliance effects are expected in real-world settings.

In order to estimate patient compliance under routine conditions, data obtained from IMS Health were used as the basis for the estimation. These data were obtained on the basis of 1869 Dutch mRCC patients treated with sunitinib. Physician records have been used in order to determine patient compliance at different points in time. According to these data the median SUN compliance rate at 3, 6, and 9 months of SUN therapy was 74%, 72%, and 71%, respectively.

As there are currently no published data on PAZ patient compliance available, it was assumed that the compliance rates are comparable to SUN. We performed analyses using the conservative estimates of 90%, 80%, and 70% patient compliance for the TKIs, respectively.

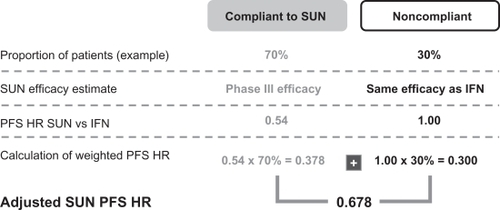

In order to simulate the compliance impact on the PFS of the TKIs an adjustment of the PFS HR was performed. As no clinical trial data are available that show the effectiveness impact of noncompliance, it was conservatively assumed that the PFS HR of noncompliant patients is ‘1’, which means the same efficacy as for IFN, and that the published Phase III efficacy refers to the compliant patients.

The detailed steps taken to estimate the real-world effectiveness (adjusted TKI PFS HR), depending on patient compliance, are shown in , using a 70% SUN patient compliance as an example. The same approach was applied for all scenarios analyzed.

Figure 4 Patient compliance PFS adjustment methodology.

As BEV is infused intravenously, the patient either visits the physician to receive the injection or decides to stop therapy by not attending. Even though many patients self-administer the subcutaneous IFN injections (in combination with BEV), which might be a potential compliance issue, downdosing of IFN has been shown to improve tolerability and maintain efficacy.Citation21 Hence it was assumed that missing an IFN injection has a limited impact on the PFS HR of BEV+IFN, so no patient compliance impact on BEV+IFN therapy was simulated.

Results

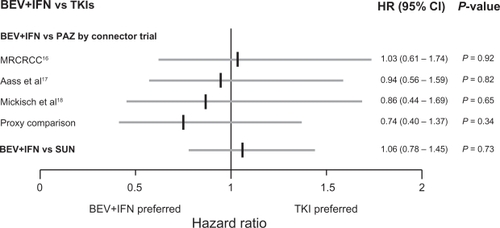

The indirect efficacy comparison, shown in , resulted in a statistically nonsignificant PFS difference of BEV+IFN vs SUN (ITC HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.78–1.45; P = 0.73) and of BEV+IFN vs PAZ (range based on different connector trials; ITC HR: 0.74–1.03; P = 0.34–0.92).

Figure 5 Indirect efficacy comparison results PFS HR of BEV+IFN vs TKIs.

For the BEV+IFN vs PAZ comparison the two extreme scenarios are based on the selected connector trials, whereby using the MRCRCC trial resulted in an ITC HR of 1.03 (95% CI: 0.61–1.74; P = 0.92) and using the ‘proxy comparison’ resulted in an ITC HR of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.40–1.37; P = 0.34).

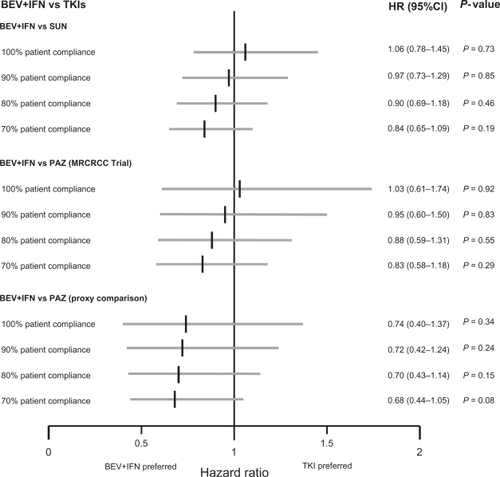

Simulating real-life patient compliance and its effectiveness impact on PFS showed an increased tendency towards BEV+IFN without reaching statistical significance, as shown in .

Figure 6 Indirect effectiveness comparison results PFS HR of BEV+IFN vs TKIs.

For the comparison of BEV+IFN vs PAZ simulations have been performed for the extreme scenarios, which means the connector trials producing the highest ITC HR (MRCRCC Trial) and the lowest ITC HR (proxy comparison) have been analyzed.

Discussion

Comparing the PFS efficacy and effectiveness of BEV+IFN vs the TKIs SUN and PAZ in first-line mRCC therapy failed to show a significant tendency in favor of one particular targeted therapy approach. Additionally, the influence of patient compliance on the PFS was investigated. This indirect effectiveness assessment indicates that the PFS outcomes with regard to TKIs might be lower in real-world settings. However the observed tendency towards a better effectiveness of BEV+IFN failed to reach statistical significance.

The main limitation is that our findings are based on indirect evidence. Such an indirect treatment comparison has to be regarded as a complementary assessment to clinical trials, because it cannot substitute direct evidence. However, in the absence of any head-to-head comparison, the indirect treatment comparison approach should be regarded as the most valuable way of estimating treatment effects in a statistically accurate manner.

Another limitation is that there is no matching connector trial available in order to determine an exact ITC hazard ratio for the comparison of BEV+IFN vs PAZ. The lack of an adequate connector trial, comparing IFN vs PLA, was overcome by using different but the most suitable IFN studies in order to enable a bridge to be built between the PAZ and the BEV+IFN PFS outcomes. Furthermore, an additional ‘proxy comparison’ was performed that is based on assuming constant hazards to estimate a HR of IFN vs PLA based on the available Phase III evidence. The authors would like to point out that the application of constant hazards should be performed very carefully but in this special case (no adequate connector trial available) it was decided to perform this analysis to test the credibility of the bridging trials’ HR on the ITC results. As no statistically significant difference was observed when comparing the PFS HR of BEV+IFN vs PAZ, irrespective of the connector trial used, the lack of an adequate bridging trial is regarded as having a limited impact on the ITC results.

Another limitation is that data on patient compliance to TKIs are currently rare. We used IMS data, which refers to the Dutch health care system, to estimate the proportion of patients who show a limited compliance to TKI therapy. As there are no real world investigations available that determine the impact of patient compliance on the PFS, we used a conservative assumption. However, further research is required in order to evaluate a more accurate link between patient compliance and its impact on efficacy.

Another aspect to be considered is the difference in patient characteristics between the pivotal trials used. According to the patient’s risk profile, the AVOREN study included fewer patients with a favorable disease prognosis; hence the PFS outcomes might be underestimated in comparison to SUN and PAZ. However, as all patients have been nephrectomized in the AVOREN trial, which is regarded as an indicator for a better disease prognosis, these small differences in prognostic patient characteristics are estimated to compensate each other.

In the past there was a consensus that SUN and BEV+IFN are equally effective in terms of PFS in first-line mRCC therapy,Citation22 which is in line with our findings. However, recent publicationsCitation23,Citation24 raised doubts about this comparable efficacy. Both papersCitation23,Citation24 focused only on investigator-assessed PFS values and pooled BEV+IFN PFS outcomes from a strictly controlled pivotal Phase III trialCitation10 and an investigator-initiated trial.Citation25 As a result of this pooling, the efficacy of BEV+IFN was decreased on the basis of a lower PFS observed in the investigator-initiated trialCitation25 compared to the pivotal trial outcomes.Citation10

In order to ensure comparability, it was expected that the authors would apply the same procedure for SUN, using the pivotal trialCitation11 and the first-line outcomes from the SUN expanded-access-study,Citation26,Citation27 but only the pivotal trial outcomes were used for SUN.

An adequate indirect comparison approach should take into account pivotal trials performed under the same conditions to be comparable and use the highest quality data (independent radiology review of PFS). Hence our approach focused on the comparison of the pivotal Phase III trials, using the highest data quality, in order to ensure comparability of therapy outcomes.

Our findings have been confirmed by another recently published indirect treatment comparison performed from the perspective of PAZ. McCann et alCitation28 concluded “that pazopanib demonstrates no reduction in efficacy compared to other approved angiogenesis inhibitors”, which is in line with our findings that say ‘there is no significant difference in first-line PFS outcomes between BEV+IFN and the TKIs SUN and PAZ’. As a consequence there is a need for other clinical decision criteria that might allow an adequate therapy selection in first-line mRCC patients. Possible guidance might be offered by aspects of available therapy sequencing options, sequential therapy outcomes, and by tolerability issues.Citation29

For example there is evidence that BEV+IFN shows a better tolerability profile if indirectly compared to SUN, which also impacts the costs of managing side effects.Citation30,Citation31 In addition, there are first retrospective analyses indicating that BEV+IFN first-line enables effective subsequent TKI therapy,Citation6,Citation32 which may lead to improved patient outcomes, taking into account the complete sequence of mRCC therapies.Citation33,Citation34

Conclusions

In conclusion, in the light of the currently available evidence, there is no statistically significant PFS difference between BEV+IFN and TKIs in first-line mRCC therapy. In terms of patient compliance there is an efficacy tendency in favor of BEV+IFN, but this fails to reach statistical significance.

These findings imply that other treatment decision criteria such as tolerability and therapy sequencing opportunities need to be considered in order to guide adequate therapy decisions.

Disclosure

This work was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche Pharmaceuticals AG.

References

- CoppinCPorzsoltFAwaAKumpfJColdmanAWiltTImmunotherapy for advanced renal cell cancerCochrane Database Syst Rev20043CD00142510908496

- Commission on Cancer, American Cancer Society. National Cancer Data Base (NCDB)2008 Available from: http://www.facs.org/cancer/ncdb/. Accessed 2010 Dec 6.

- NeseNPanerGPMallinKRitcheyJStewartAAminMBRenal cell carcinoma: assessment of key pathologic prognostic parameters and patient characteristics in 47,909 cases using the National Cancer Data BaseAnn Diagn Pathol20091311819118775

- GarciaJARiniBIRecent progress in the management of advanced renal cell carcinomaCA Cancer J Clin200757211212517392388

- MickischGHRational selection of a control arm for randomised trials in metastatic renal cell carcinomaEur Urol200343667067912767369

- EscudierBBellmuntJNegrierSFinal results of the phase III, randomized, double-blind AVOREN trial of first-line bevacizumab (BEV) + interferon-alpha-2a (IFN) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting Chicago, IL, 2009 May 29–Jun 2J Clin Oncol20092715S5020

- MotzerRJHutsonTETomczakPOverall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinomaJ Clin Oncol200927223584359019487381

- SternbergCNDavisIDMardiakJPazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trialJ Clin Oncol20102861061106820100962

- WoodsBSHawkinsNScottDANetwork meta-analysis on the log-hazard scale, combining count and hazard ratio statistics accounting for multi-arm trials: a tutorialBMC Med Res Methodol2010105420537177

- EscudierBPluzanskaAKoralewskiPBevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trialLancet200737096052103211118156031

- MotzerRJFiglinRAHutsonTESunitinib versus interferon-alfa (IFN-a) as first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Updated results and analysis of prognostic factors: Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting Chicago, IL, 2007 Jun 1–5J Clin Oncol20072518S502417971603

- BucherHCGuyattGHGriffithLEWalterSDThe results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Clin Epidemiol19975066836919250266

- WellsGASultanSAChenLKhanMCoyleDIndirect evidence: indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis2009 Available from: http://www.cadth.ca/index.php/en/hta/reports-publications/search/publication/884. Accessed 2010 Dec 6.

- SongFAltmanDGGlennyAMDeeksJJValidity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analysesBMJ2003326738747212609941

- TudurCWilliamsonPRKhanSBestLYThe value of the aggregate data approach in meta-analysis with time-to-event outcomesJ Royal Stat Soc20021642357370

- Medical Research Council Renal Cancer CollaboratorsInterferon-alpha and survival in metastatic renal carcinoma: early results of a randomised controlled trialLancet19993539146141710023944

- AassNde MulderPHMickischGHRandomized phase II/III trial of interferon alfa-2a with and without 13-cis-retinoic acid in patients with progressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Tract Cancer Group (EORTC 30951)J Clin Oncol200523184172417815961764

- MickischGHGarinAvanPHde PrijckLSylvesterRRadical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trialLancet2001358928696697011583750

- SnedecorGWCochranWGTests of hypothesesStatistical Methods8th edAmes, IAIowa State University Press19896482

- WellsGASultanSAChenLKhanMCoyleDIndirect treatment comparison software application (version 1.0)2009 Available from: http://www.cadth.ca/index.php/en/itc-user-guide/download-software. Accessed 2010 Jul 20.

- MelicharBKoralewskiPRavaudAFirst-line bevacizumab combined with reduced dose interferon-alpha2a is active in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinomaAnn Oncol20081981470147618408224

- CoppinCLeLPorzsoltFWiltTTargeted therapy for advanced renal cell carcinomaCochrane Database Syst Rev20082CD00601718425931

- MillsEJRachlisBO’ReganCThabaneLPerriDMetastatic renal cell cancer treatments: an indirect comparison meta-analysisBMC Cancer200993419173737

- Thompson CoonJSLiuZHoyleMSunitinib and bevacizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and indirect comparison of clinical effectivenessBr J Cancer2009101223824319568242

- RiniBIHalabiSRosenbergJEBevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206J Clin Oncol200826335422542818936475

- GoreMEPortaCOudardSSunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Preliminary assessment of toxicity in an expanded access trial with subpopulation analysis: Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting Chicago, IL, 2007 Jun 1–5J Clin Oncol20072518S5010

- GoreMESzczylikCPortaCSafety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded-access trialLancet Oncol200910875776319615940

- McCannLAmitOPanditeLAmadoRAn indirect comparison analysis of pazopanib versus other agents in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers SymposiumSan Francisco, CA2010 Mar 5–7 [Suppl; abstr # 413].

- PortaCBellmuntJEisenTSzczylikCMuldersPTreating the individual: The need for a patient-focused approach to the management of renal cell carcinomaCancer Treat Rev2010361162319819078

- ProcopioGVerzoniEBajettaECosts of managing side effects in the treatment of first line metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Italy: Bevacizumab + Interferon alpha2a compared with Sunitinib: Proceedings of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress, Stockholm, Sweden, 2008 Sep 12–16Ann Oncol2008198601P

- MickischGGoreMEscudierBProcopioGWalzerSNuijtenMCosts of managing adverse events in the treatment of first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma: bevacizumab in combination with interferon-alpha2a compared with sunitinibBr J Cancer20101021808619920817

- BracardaSBellmuntJNegrierSWhat is the impact of subsequent antineoplastic therapy on overall survival (OS) following first-line bevacizumab (BEV)/interferon-alpha2a (IFN) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)? Experience from AVOREN: Proceedings of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Multidisciplinary Congress, Berlin, Germany, 2009 Sep 20–24Eur J Cancer200972P7126

- MelicharBHow can second-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma help to define an overall management strategy?Oncology2009772829119602908

- EscudierBGoupilMGMassardCFizaziKSequential therapy in renal cell carcinomaCancer200911510 Suppl2321232619402067