?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

The study objective was to develop an economic model to assess projected costs of lost productivity associated with premature deaths due to veno-occlusive disease (VOD)/ sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) with multiorgan dysfunction (MOD) among patients in the US who underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT) in 2013.

Methods

Data sources included the US Census Bureau and Department of Health, epidemiologic research organizations, and medical research literature. The model considered only lost productivity associated with premature death, with lifetime salary assumed to reflect productivity. Average annual salary was assumed to be the same for HSCT survivors and the general population, with a working age range between 18 and 65 years. Key data inputs included number of HSCTs by graft type (allogeneic and autologous) performed in the US in 2013, HSCT-related mortality, mortality associated with VOD/SOS with MOD, and life-expectancy reduction for HSCT survivors vs the general population. Excess mortality equaled total deaths among patients with VOD/SOS and MOD minus deaths in these patients due to causes other than VOD/SOS with MOD.

Results

Among 18,284 patients who underwent HSCT in the US in 2013, the model estimated that 361 excess deaths due to VOD/SOS with MOD occurred (158 following allogeneic and 203 after autologous transplants). These deaths accounted for total lost work productivity of 5,990 years and $124,212,173 in lost wages, averaging 17 years and $343,791 per patient. A sensitivity analysis incorporating adjustment factors for epidemiologic and economic inputs calculated total financial loss of $84 million to $194 million.

Limitation

Estimates of post-HSCT VOD/SOS with MOD incidence and mortality were approximated, due to changing HSCT practices.

Conclusion

Premature death due to VOD/SOS with MOD imposes a substantial economic burden in this population in terms of lost productivity. Additional studies of this economic burden are warranted.

Introduction

Hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD), also called sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS), is a potentially fatal complication of hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT).Citation1,Citation2 VOD/SOS results from a pathophysiological cascade characterized by toxic injury to sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes in zone 3 of the hepatic acinus caused by the HSCT-conditioning regimen, and has also been observed to occur after nontransplant-associated chemotherapy.Citation1,Citation2 The estimated incidence of VOD/SOS among patients undergoing HSCT varies, but a pooled analysis found rates of approximately 8.7% and 12.9% among patients receiving autologous and allogeneic transplants, respectively.Citation3 Clinical characteristics of VOD/SOS typically include hepatomegaly, weight gain, increased bilirubin (>2 mg/dL), and ascites that usually occur within 3 weeks post-HSCT.Citation3,Citation4 VOD/SOS has traditionally been diagnosed based on the Baltimore criteria (≤21 days post-HSCT, bilirubin ≥2 mg/dL, and two or more of hepatomegaly, ascites, and weight gain ≥5%)Citation5 or the modified Seattle criteria (≤20 days post-HSCT, with two or more of bilirubin ≥2 mg/dL, hepatomegaly/right upper-quadrant pain, and >2% weight gain [sometimes ≥5%]).Citation6,Citation7 However, experts have recently called for revision of these diagnostic criteria to include a broader range of clinical presentations and updates to increase diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.Citation2,Citation8,Citation9

The severity, course, and outcome of VOD/SOS have been difficult to predict.Citation4,Citation10,Citation11 Severe VOD/SOS was traditionally defined retrospectively as death or nonresolution of symptoms by day +100.Citation1 More recently, however, concomitant multiorgan dysfunction (MOD; eg, renal and/or pulmonary dysfunction) has been widely acknowledged to be a critical characteristic of severe VOD/SOS, irrespective of how the VOD/SOS pathophysiological cascade is triggered, allowing for practical, prospective assessment and treatment.Citation2,Citation4 Further, the European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation has proposed age-specific grading criteria for pediatric and adult patients, which may provide earlier identification of patients with severe disease prior to clinical MOD.Citation8,Citation9

VOD/SOS with MOD develops iñ20%–40% of patients with VOD/SOS who received HSCT, most frequently after allogeneic transplant,Citation11–Citation14 and may be associated with mortality rates >80%.Citation3 In addition, VOD/SOS was estimated to increase first-year, per-patient direct HSCT costs by 42% or US $41,702 and 150% for patients with VOD/SOS and MOD.Citation15 Therefore, VOD/SOS and MOD pose significant economic burdens in direct medical costs.

Research to ascertain work-productivity loss associated with premature death due to VOD/SOS, however, is currently lacking. This parameter is particularly important to assess for post-HSCT patients, because ~70% of patients who receive HSCT are aged 60 years or younger,Citation16 ie, within or before the prime years of life for work productivity. The economic model used for this study was developed to evaluate the cumulative indirect costs of lost productivity associated with premature deaths due to VOD/SOS with MOD among HSCT patients in the US.

Methods

Overall design

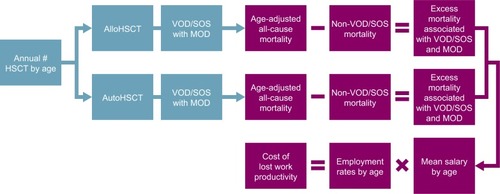

This was an Excel-based economic model of productivity loss due to premature death associated with VOD/SOS and MOD in patients who had undergone HSCT in the US (). Controls included HSCT survivors and were modeled using US population data, such as US census and economic data, on employment rates and wages. Only lost work-related productivity of the patient associated with premature death was considered. Lost productivity related to disability, school, or daily activities was not considered. The age of the working population was considered to be 18–65 years.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the model.

Abbreviations: alloHSCT, allogeneic HSCT; autoHSCT, autologous HSCT; HSCT, hematopoietic stem-cell transplant; MOD, multiorgan dysfunction; SOS, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; VOD, veno-occlusive disease.

Model inputs

Epidemiological model inputs for the total HSCT population included the number of transplants by type in the USCitation16 and overall posttransplant mortality ().Citation17

Table 1 Allogeneic and autologous HSCT and mortality by age-group (preretirement population)

Epidemiologic inputs for VOD/SOS populations included:

incidence of VOD/SOS by HSCT-graft type (12.9% allogeneic, 8.7% autologous;Citation3 hepatic VOD/SOS was first defined by the ICD 10 in October 2015)

○ incidence of VOD/SOS for allogeneic HSCT patients identified by modified Seattle criteria and Baltimore criteria were estimated to be 13.8% and 8.8%, respectivelyCitation12

incidence of VOD/SOS with MOD among HSCT patients with VOD/SOS (27.6%), based on results from a study using a retrospective definition of severityCitation11

mortality rate due to VOD/SOS with MOD (84.3%) from a pooled analysis of 19 studies, which used varied definitions of severityCitation3

○ mortality was assumed to be directly related to VOD/ SOS pathophysiology, irrespective of graft typeCitation19

Model inputs for control populations included:

life expectancy by age-group in the general populationCitation18

US general population averages for annual salary and employment rate by age-group ()

reduction in life expectancy for HSCT survivors vs the general population by age-group ()

reduced employment rate in HSCT survivors, defined as percentage of patients receiving HSCT who have not returned to their previous level of employment, presented as a weighted average of employment-rate reductions for autologous HSCT and allogeneic HSCT

reductions in employment rate in HSCT survivors by years following HSCT, estimated to be 40% after 1 year and 31% after 2 years, based on a published analysis in 328 patients;Citation24 the rate was assumed to be 0 after 3 years and onward

Table 2 General population average annual salary, employment rate, and reduction in life expectancy for HSCT patients by age-group

Model data-input sources

Sources of the data inputs for this model included published literature; the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Census Bureau, and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Model outputs

Excess mortality was calculated as the estimated total number of deaths among patients with VOD/SOS and MOD post-HSCT, based on incidence and mortality rates reported in the literature,Citation3,Citation11 minus the estimated number of deaths among patients with VOD/SOS and MOD due to factors other than VOD/SOS with MOD (eg, HSCT, progressive disease, infection, graft-versus-host disease, and natural causes):

Specifically, numbers of patients receiving allogeneic and autologous HSCT were multiplied by rates of VOD/SOS from the literature (12.9% and 8.7%, respectively), then for MOD (27.6%), and finally for death due to MOD (84.3%). These numbers were then adjusted by subtracting all-cause mortality post-HSCT (3%–43% depending on graft type and age). Lost productivity years resulting from premature death were calculated as the number of years between initial age or age 18 years, whichever was higher, and retirement age (65 years) or life-expectancy estimates, whichever was lower. Total lost productivity years and indirect costs by age were obtained by multiplying each per-patient value by the number of excess deaths in each age-group. Work-productivity loss was expressed as the cumulative lost salary for all projected work years contributed by a patient, with a 3% discount for each additional year. Productivity loss due to VOD/SOS with MOD was calculated in 2014 US$ and compared with HSCT survivors.

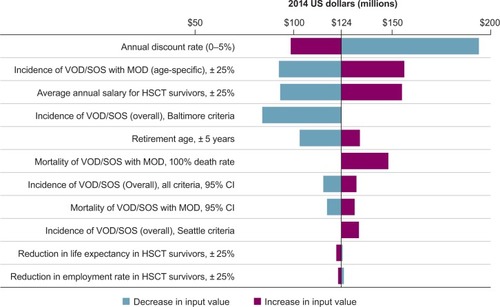

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the effect of various epidemiological and economic parameters, such as incidence and mortality of VOD/SOS with MOD, retirement age, average salaries, and reductions in employment rate and life expectancy, on the observed results, with a range of low and high costs estimated for each variable based on the sources used or model-based calculations ().

Table 3 Deterministic sensitivity analysis modeling variables of work-productivity loss due to premature death from VOD/SOS with MOD vs HSCT survivors without VOD/SOS

Results

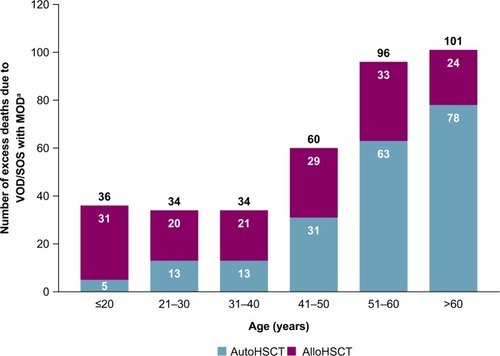

Based on this model for the year 2013, 361 excess deaths per year in the US are expected due to VOD/SOS with MOD in the HSCT population, including 203 excess deaths in patients undergoing autologous HSCT — the great majority in patients aged >50 years — and 158 excess deaths in patients receiving allogeneic HSCT (). As shown in , 18,284 patients received HSCT in 2013, including 10,542 who received autologous and 7,742 who received allogeneic HSCT.Citation17 Estimated incidence of VOD/SOS is incrementally higher in allogeneic vs autologous HSCT patients (12.9% vs 8.7%),Citation3 which resulted in a slightly higher estimated number of VOD/SOS cases in allogeneic vs autologous HSCT patients in the study sample (999 vs 917, respectively). In addition, given that the estimated incidence of VOD/SOS with MOD in patients with VOD/ SOS (27.6%)Citation11 and its associated mortality rate (84.3%)Citation3 were assumed to be the same in each group,Citation19 deaths for patients with VOD/SOS with MOD were estimated to be slightly higher in allogeneic vs autologous HSCT (232 vs 213, respectively). However, such deaths could be due to any causes among patients with VOD/SOS with MOD, and may include such reasons as HSCT itself. Therefore, the “excess” death due to VOD/SOS with MOD was further calculated by taking into consideration all-cause mortality among patients who received HSCT, which is reported to be much higher in patients who received allogeneic vs autologous HSCT (28%–43% vs 3%–8% across different age-groups; ).Citation17 Therefore, a larger proportion of patients with allogeneic vs autologous HSCT were estimated to die from reasons associated with HSCT itself or various causes other than VOD/SOS with MOD. After subtracting these patients, the estimated “excess” mortality from VOD/SOS with MOD was slightly lower in allogeneic vs autologous HSCT patients (158 vs 203, respectively).

Figure 2 Annual number of excess deaths in the total population across all ages (including patients aged >65 years).

Abbreviations: alloHSCT, allogeneic HSCT; autoHSCT, autologous HSCT; HSCT, hematopoietic SCT; MOD, multiorgan dysfunction; SOS, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; VOD, veno-occlusive disease.

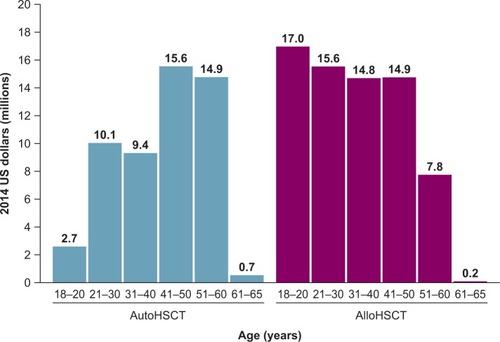

For patients who died in 2013, death due to VOD/SOS with MOD among HSCT patients was associated with a total of 5,990 lost work-productivity years and an indirect cost of $124,212,173 in 2014 US$ (autologous, $53,580,337; allogeneic, $70,631,836) compared with HSCT survivors, averaging 17 lost work-productivity years at an indirect cost of $343,791 per patient ().

Table 4 Lost work-productivity years and indirect costs (2014 US$) due to excess deaths from VOD/SOS with MOD vs HSCT survivors by age-group (preretirement population)

Patients with VOD/SOS and MOD who had undergone allogeneic HSCT were younger on average and had greater estimated work-productivity loss ($71 million over time for patients receiving HSCT in 2013) compared with patients who had received autologous HSCT ($54 million; ).

Figure 3 Total work-productivity loss associated with premature death due to VOD/SOS with MOD by age and graft type compared to HSCT survivors.

The deterministic sensitivity analysis using epidemiological and economic inputs (), including variations in the incidence and mortality of VOD/SOS with MOD, retirement age, average salaries, and reductions in employment rate and life expectancy, showed productivity loss of premature death due to VOD/SOS with MOD in all scenarios (). These ranged from a low of ~$84 million when confined to patients diagnosed with VOD/SOS via Baltimore criteriaCitation5 to a high of $194 million based on the high end of the annual discount rate. Other factors to which the model was most sensitive were incidence of VOD/SOS with MOD and average annual salary for HSCT survivors.

Discussion

Existing studies have reported high direct medical costs associated with HSCT, with VOD/SOS, and with VOD/SOS with MOD.Citation25,Citation26 Specifically, direct medical costs associated with hospitalization for those with VOD/SOS and MOD have been evaluated and reported to be $140,000–$250,000 per patient,Citation15,Citation27 However, data have not been available on the indirect costs expected to be a consequence of potentially fatal complications, such as VOD/SOS with MOD. Although VOD/SOS with MOD is a comparatively rare complication of HSCT, this model found that VOD/SOS with MOD represents a substantial indirect cost to society. The model estimates that in each year, patients who develop VOD/SOS with MOD will incur total lifetime work-productivity loss of over $124 million due to reduced life expectancy. Results of a sensitivity analysis demonstrated that total productivity loss could be as high as $194 million per year. The estimated average total productivity loss per patient was approximately $344,000. This model likely underestimates the total indirect costs of premature death due to VOD/SOS with MOD, as it does not include productivity loss among children and caregivers, patients aged >65 years who might otherwise continue to work (30%),Citation20,Citation21 or unpaid workers (eg, homemakers and stay-at-home parents). Moreover, VOD/SOS with MOD may occur outside the HSCT setting, such as high-dose chemotherapy alone.Citation2,Citation28

These data are all the more important to consider, given the high and growing prevalence of patients undergoing HSCT.Citation4,Citation29,Citation30 Of the 11.7 million people who had cancer in the US in 2007, 8% (936,000) were estimated to have hematologic cancers.Citation29 In addition, CIBMTR data indicate that use of HSCT has increased steadily over the past 30 years, with a current annual rate of more than 21,000 patients receiving this procedure in the US, and is projected to continue increasing.Citation31–Citation33 Along with this general increase, the proportion of patients aged ≥60 years among all patients receiving autologous and allogeneic HSCT rose markedly, from less than 20% and 5%, respectively, in the period 1993–1999 to 50% and 30%, respectively, in 2015.Citation33 Nonetheless, the majority of HSCT patients receiving either type of transplant remain of working age or have their entire working lives before them: as of 2009, CIBMTR data showed that 14% of all HSCT recipients were aged <18 years.Citation29 Therefore, the productivity loss due to premature death in the total HSCT population is likely to be of considerable magnitude, as demonstrated by the present data.

Among long-term HSCT survivors, 10- to 20-year survival has generally been estimated in studies to be in the range of 70%–90%.Citation22,Citation34–Citation40 For patients surviving 10 years, life expectancy may approach that of the general population, although this cohort continues to experience increased morbidity and mortality risks.Citation22,Citation23,Citation34,Citation40–Citation42 Therefore, premature death occurring shortly after HSCT imposes a considerable indirect cost in lost decades of productive life for a large number of patients in the US, as indicated by this analysis.

The current analysis outlines the expected indirect costs associated with VOD/MOD-related mortality. However, the difficulties among the overall population of HSCT survivors are important to consider in the present context, because they illustrate that premature death represents only a portion of the total indirect cost related to VOD/SOS with MOD. Some studies in the literature have demonstrated the adverse impact on work productivity in the years following HSCT. For example, one study found that ~40%–60% of adult survivors of allogeneic transplant who were employed pretransplant were employed at 1 year post-HSCT.Citation24,Citation43 Further, among those with full-time employment, survivors reported that they could accomplish 80%–87% of what they had been able to achieve before the transplant.Citation43 In another study, a third of allogeneic transplant recipients who had been employed prior to HSCT were no longer employed in the following year; in the overall survey population, 26% reported that household income had decreased >50%.Citation44 However, a separate study looking at longer-term outcomes found that 72% of HSCT patients were working at 10 years posttransplant, which was similar to the 74% rate in matched controls.Citation23 A Swiss study in 203 patients at 12-years post-HSCT (median age 50 years) found that while 77% were working full- or part-time, 37% were receiving a work-disability pension compared to an expected pension incidence of 3.2% of the Swiss working population.Citation45 Employment was also examined in a study of adult survivors of pediatric allogeneic transplantation, which found that secondary-school graduation rates for girls were similar to those of the general population, but the rate for boys was approximately half of population norms; even so, job distribution was similar to that of the general population.Citation46 Besides employment difficulties, HSCT survivorship may be associated with costs and work productivity loss due to hospitalizations and follow-up care resulting from infectious and noninfectious complications frequently encountered with HSCT.Citation24,Citation34

The present analysis helps quantify an important aspect of the burden of illness of VOD/SOS with MOD, advance this area of research, and provide a basis for future studies. The estimated work-productivity losses per patient of approximately $344,000 associated with death due to VOD/SOS with MOD found in this study, combined with direct costs over time of $100,000 to more than $400,000 for HSCT aloneCitation15,Citation25,Citation26 and approximately $150,000 more for additional hospital costs due to VOD/SOS and MOD,Citation15,Citation27 provide a more complete and accurate assessment of the total potential costs of HSCT. The present sensitivity analysis also demonstrates the qualitative robustness of the model. In addition, these data serve to remind physicians of an important clinical association — the potential for VOD/SOS to lead to MOD — which may be overlooked in general assessments of the economic burden of HSCT.

However, because the economic impact of VOD/SOS with MOD is not well characterized in the literature, there are limitations on the available input data. For example, reporting to CIBMTR is voluntary, and it is estimated that the database captures 60%–90% of related donor allogeneic transplants and 65%–75% of autologous transplants.Citation33 Further, the diagnostic code for VOD/SOS was introduced in the ICD10, complicating identification of VOD/SOS (and VOD/SOS with MOD and VOD/SOS-associated mortality) before 2015. Estimates for incidence of VOD/SOS, associated MOD, and mortality due to VOD/SOS with MOD have been variable over time as clinical practice in HSCT has changed: some researchers have found higher incidence of VOD/SOS over time and across studies,Citation3 while others have reported decreasing incidence in single-center settings.Citation12 Although increasing the use of reduced intensity conditioning may affect incidence of VOD/SOS,Citation2 one study in postallogeneic patients reported an overall VOD/SOS rate of 9% in those given reduced-intensity conditioning.Citation47 Mortality due to causes other than VOD/SOS and MOD was estimated, and was assumed to be the same as HSCT patients who had died from causes other than VOD/SOS and MOD. Therefore, additional research is needed to assess more completely the total costs of this important, high-risk complication of HSCT. In addition, as this model does not include productivity loss among children and caregivers, patients aged >65 years who might otherwise continue to work (30%),Citation20,Citation21 and unpaid workers (eg, homemakers and stay-at-home parents), it likely underestimates total indirect costs. Of note, VOD/SOS in the absence of MODCitation12,Citation48 is also associated with early mortality; however, this lost productivity is not included in the model. The reductions in employment rate in HSCT survivors by years following HSCT, estimated to be 40% after 1 year and 31% after 2 years, were also based on limited data: a study in 328 patients.Citation24

Conclusion

VOD/SOS with MOD imposes a substantial economic burden in terms of excess deaths and lost productivity. This model, focusing on work-productivity loss due to premature death, found that VOD/SOS with MOD could represent a cumulative indirect cost of $124 million and as high as $194 million for US patients treated in 2013 in 2014 US$, with an estimated average cost of approximately $344,000 per patient. This cost is in addition to an estimated mean direct hospitalization cost of $250,000 per patient associated with VOD/SOS and MOD post-HSCT. Future research is warranted to assess the additional indirect costs associated with VOD/SOS with and without MOD.

Author contributions

All authors were responsible for the study conception and design, involved in the collection and assembly of data, participated in study-data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing, and provided their final approval of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals Inc, the manufacturer of defibrotide. The authors thank Larry Deblinger and The Curry Rockefeller Group, LLC of Tarry-town, NY for providing medical writing support and editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, and copy editing, and fact-checking, which was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). Jazz Pharmaceuticals also reviewed and edited the publication for scientific accuracy.

Disclosure

WT and ZYZ are consultants for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. KFV is an employee of Jazz Pharmaceuticals and holds stock and/ or stock options in Jazz Pharmaceuticals. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BearmanSIThe syndrome of hepatic veno-occlusive disease after marrow transplantationBlood19958511300530207756636

- MohtyMMalardFAbecassisMSinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease: current situation and perspectives-a position statement from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT)Bone Marrow Transplant201550678178925798682

- CoppellJARichardsonPGSoifferRHepatic veno-occlusive disease following stem cell transplantation: incidence, clinical course, and outcomeBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201016215716819766729

- DignanFLWynnRFHadzicNHaemato-oncology task force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology and the British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. BCSH/BSBMT guideline: diagnosis and management of veno-occlusive disease (sinusoidal obstruction syndrome) following haematopoietic stem cell transplantationBr J Haematol2013163444445724102514

- JonesRJLeeKSBeschornerWEVenoocclusive disease of the liver following bone marrow transplantationTransplantation19874467787833321587

- McDonaldGBHindsMSFisherLDVeno-occlusive disease of the liver and multiorgan failure after bone marrow transplantation: a cohort study of 355 patientsAnn Intern Med199311842552678420443

- CorbaciogluSCesaroSFaraciMDefibrotide for prophylaxis of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in paediatric haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trialLancet201237998231301130922364685

- MohtyMMalardFAbecassisMRevised diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a new classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow TransplantationBone Marrow Transplant201651790691227183098

- CorbaciogluSCarrerasEAnsariMDiagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in pediatric patients: a new classification from the European society for blood and marrow transplantationBone Marrow Transplant201853213814528759025

- BearmanSIAndersonGLMoriMHindsMSShulmanHMMcDonaldGBVenoocclusive disease of the liver: development of a model for predicting fatal outcome after marrow transplantationJ Clin Oncol1993119172917368355040

- CarrerasEBertzHArceseWIncidence and outcome of hepatic veno-occlusive disease after blood or marrow transplantation: a prospective cohort study of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Chronic Leukemia Working PartyBlood19989210359936049808553

- CarrerasEDíaz-BeyáMRosiñolLMartínezCFernández-AvilésFRoviraMThe incidence of veno-occlusive disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has diminished and the outcome improved over the last decadeBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201117111713172021708110

- StrouseCRichardsonPPrenticeGDefibrotide for treatment of severe veno-occlusive disease in pediatrics and adults: an exploratory analysis using data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant ResearchBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20162271306131227108694

- CesaroSPillonMTalentiEA prospective survey on incidence, risk factors and therapy of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in children after hematopoietic stem cell transplantationHaematologica200590101396140416219577

- CaoZVillaKFLipkinCBRobinsonSBNejadnikBDvorakCCBurden of illness associated with sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantationJ Med Econ201720887188328562132

- PasquiniMCWangZCurrent uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR summary slides [webpage on the Internet]2013 [cited 2016 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.cibmtr.org/ReferenceCenter/SlidesReports/SummarySlides/Documents/2013%20Summary%20Slides-%20Final%20Web%20Version%20%20V2%204.14.2014.pptxAccessed November 22, 2017

- Health Resources and Services AdministrationUS patient survival report [webpage on the Internet]RockvilleUS Department of Health and Human Services [cited 2016 20 Apr]. Available from: http://blood-cell.transplant.hrsa.gov/RESEARCH/Transplant_Data/US_Tx_Data/Survival_Data/survival.aspxAccessed November 22, 2017

- XuJMurphySLKochanekKDBastianBADeaths: final data for 2013Natl Vital Stat Rep2016642111926905861

- CarrerasERosiñolLTerolMJVeno-occlusive disease of the liver after high-dose cytoreductive therapy with busulfan and melphalan for autologous blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patientsBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200713121448145418022574

- United States Census BureauHistorical income tables: people. Table P-10. Age—people (both sexes combined) by median and mean2013 webpage on the InternetWashington, DCUS Department of Commerce [updated Aug 10, 2017] Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-people.htmlAccessed November 22, 2017

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [webpage on the Internet]Labour force statistics by sex and age Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=LFS_D#Accessed 2015 Feb23

- MartinPJCountsGWAppelbaumFRLife expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantationJ Clin Oncol20102861011101620065176

- SyrjalaKLLangerSLAbramsJRStorerBEMartinPJLate effects of hematopoietic cell transplantation among 10-year adult survivors compared with case-matched controlsJ Clin Oncol200523276596660616170167

- LeeSJFaircloughDParsonsSKRecovery after stem-cell transplantation for hematologic diseasesJ Clin Oncol200119124225211134219

- MajhailNSMauLWDenzenEMArnesonTJCosts of autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States: a study using a large national private claims databaseBone Marrow Transplant201348229430022773126

- BroderMSQuockTPChangEThe cost of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in the United StatesAm Health Drug Benefits201710736637429263771

- DvorakCCNejadnikBCaoZRobinsonSBLipkinCVillaKFHospital cost associated with veno-occlusive disease (VOD) in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT)Poster presented at: 57th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and ExpositionDecember 7 2015Orlando, FL

- KantarjianHMDeangeloDJAdvaniASHepatic adverse event profile of inotuzumab ozogamicin in adult patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results from the open-label, randomised, phase 3 INO-VATE studyLancet Haematol201748e387e39828687420

- MajhailNSTaoLBredesonCPrevalence of hematopoietic cell transplant survivors in the United StatesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201319101498150123906634

- GooleyTAChienJWPergamSAReduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantationN Engl J Med2010363222091210121105791

- D’SouzaALeeSZhuXPasquiniMCurrent use and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United StatesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20172391417142128606646

- MajhailNSFarniaSHCarpenterPAIndications for autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: guidelines from the American Society for Blood and Marrow TransplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant201521111863186926256941

- PasquiniMCZhuXCurrent uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): 2016 summary slides [webpage on the Internet]2016 Available from: https://www.cibmtr.org/referencecenter/slides-reports/summaryslides/Pages/index.aspx#DownloadSummarySlidesAccessed October 31, 2017

- MajhailNSRizzoJDSurviving the cure: long term followup of hematopoietic cell transplant recipientsBone Marrow Transplant20134891145115123292238

- MajhailNSBajorunaiteRLazarusHMLong-term survival and late relapse in 2-year survivors of autologous haematopoietic cell transplantation for Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomaBr J Haematol2009147112913919573079

- MajhailNSBajorunaiteRLazarusHMHigh probability of long-term survival in 2-year survivors of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for AML in first or second CRBone Marrow Transplant201146338539220479710

- BhatiaSFranciscoLCarterALate mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor StudyBlood2007110103784379217671231

- GoldmanJMMajhailNSKleinJPRelapse and late mortality in 5-year survivors of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phaseJ Clin Oncol201028111888189520212247

- WingardJRMajhailNSBrazauskasRLong-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantationJ Clin Oncol201129162230223921464398

- Nivison-SmithISimpsonJMDoddsAJMaDDSzerJBradstockKFRelative survival of long-term hematopoietic cell transplant recipients approaches general population ratesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant200915101323133019747641

- VanderwaldeAMSunCLLaddaranLConditional survival and cause-specific mortality after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematological malignanciesLeukemia20132751139114523183426

- BakerKSArmenianSBhatiaSLong-term consequences of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: current state of the scienceBiol Blood Marrow Transplant2010161 SupplS90S9619782145

- KirchhoffACLeisenringWSyrjalaKLProspective predictors of return to work in the 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantationJ Cancer Surviv201041334419936935

- KheraNChangYHHashmiSFinancial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantationBiol Blood Marrow Transplant20142091375138124867778

- TichelliAGerullSHolbroAInability to work and need for disability pension among long-term survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantationBone Marrow Transplant201752101436144228650451

- FreyconFTrombert-PaviotBCasagrandaLAcademic difficulties and occupational outcomes of adult survivors of childhood leukemia who have undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and fractionated total body irradiation conditioningPediatr Hematol Oncol201431322523624087985

- TsirigotisPDResnickIBAvniBIncidence and risk factors for moderate-to-severe veno-occlusive disease of the liver after allogeneic stem cell transplantation using a reduced intensity conditioning regimenBone Marrow Transplant201449111389139225068424

- YakushijinKAtsutaYDokiNSinusoidal obstruction syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and outcomesBone Marrow Transplant201651340340926595082