Abstract

Background

AML is a rapidly progressing bone marrow cancer, with poor survival rates compared to other types of leukemia. IC and NIC as well as BSC treatment options are available; however, there is scant published literature on the impact of disease and treatment on the HRQoL in patients receiving NIC.

Aim

This study determined the HRQoL among NIC AML patients.

Materials and methods

Embase, Medline, Cochrane database, and conference abstracts were searched using the prespecified PICOS criteria from January 2000 to November 2017 for studies reporting HRQoL and patient preference utilities in NIC AML. Studies on patients with RAEB-t MDS, randomized clinical trials (RCTs), prospective observational studies, and patient surveys were included, while systematic reviews and meta-analyses were used for bibliographic searching.

Results

Thirteen records from 12 original studies were identified. These included five records from four RCTs, three prospective studies, four patient survey studies, and one cost-effectiveness analysis. At baseline, NIC AML patients had poor HRQoL scores especially in fatigue (33) and GHS (50) on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better health. Low baseline HRQoL scores, especially PF and fatigue (<50) were shown to be significant independent predictors of poor survival. Clinical responders demonstrated meaningful improvements, especially in PF and fatigue, along with other health domains after being treated with NIC agents across several studies.

Conclusion

HRQoL is poor for patients with NIC AML; measures such as fatigue and PF at baseline have been identified as independent prognostic factors for overall survival with several studies showing improvement in both domains with treatment. RCTs should incorporate evaluation of treatment impact on patients’ PF and fatigue as important measures of effectiveness.

Introduction

AML is generally a disease of older people and is uncommon before the age of 45 years.Citation1,Citation2 Within USA, the average age of a patient with AML is 68 years, with about 19,520 new cases of AML patients and 10,670 deaths from AML.Citation3 AML is an aggressive disease with an unfavorable prognosis and accounts for 25% of acute leukemias in adults worldwide, with an estimated 5-year survival of 26% in USA.Citation3,Citation4 Prior epidemiological research has shown that age >70 years was the strongest predictor to receive nonintensive treatment compared to IC in patients newly diagnosed with AML based in an academic population-based registry study, whereas younger age (<60 years) was inversely associated with IC.Citation5 Treatments for these patients are limited, particularly for those with poor performance status, comorbidities, and unfavorable cytogenetic abnormalities.Citation6–Citation8

The standard of care for fit patients with AML is IC, which includes the “7+3” regimen, comprising 7 days of treatment with cytarabine combined with 3 days of treatment with an anthracycline.Citation7,Citation9,Citation10 For unfit patients with AML who are not eligible for IC, the NCCN guidelines include therapy with HMA such as decitabine, azacitidine, and low-dose cytarabine (LDAC); similarly, the ELN guidelines state that treatment alternatives for unfit patients are limited to BSC, low-intensity treatment, or clinical trials with investigational drugs.Citation11,Citation12 Low-intensity options are either LDAC or therapy with HMA. LDAC is generally well tolerated and produces complete remission rates in the order of 15–25%; however, overall survival (median, 5–6 months) is unsatisfactory.Citation12 Even though AML is primarily a disease of older adults,Citation1,Citation2,Citation7,Citation13 age is not the only factor for determining treatment with intensive or NIC or BSC. Treatment decisions for patients with AML may be impacted by patient-specific factors such as cytogenetics, initial blood counts, performance status, comorbidities, daily life activities that have led to the changes in chemotherapy regimens, treatment-related mortality, and toxicity risk.Citation13

It has also become increasingly important to assess the impact of AML and its treatments on HRQoL since not all patients are eligible for IC. The awareness of HRQoL is a broad concept that covers different domains such as physical, mental, social, and role functioning.Citation14,Citation15 Information about the impact on HRQoL can be used for different purposes. First, this information is useful for treatment allocation; currently, treatment allocation in AML depends largely on the effectiveness of the different treatments in terms of survival.Citation14,Citation16,Citation17 Furthermore, HRQoL information provides insight into specific health problems and treatment needs of patients with AML. The identification of these health problems can help in the effort to improve current treatments and develop new treatment modalities.Citation14,Citation18,Citation19 For example, results from a prospective evaluation indicated that negative effects of treatment on MDS patient’s quality of life were limited to the time in the hospital, specifically intensively treated patients spent 79% of their remaining lifetime in hospitals, whereas nonintensively treated patients spent 14%.Citation20,Citation21 The HRQoL of these patients and their ability to function improved since they left the hospital and scores after discharge were similar as to pretreatment scores.Citation20,Citation21 The symptom burden for AML patients is significant and involves some of the following: general (weight loss/loss of appetite, fever); low count of red blood cells (anemia); tiredness/fatigue, weakness, and dyspnea (shortness of breath); low count of white blood cells (leukopenia/neutropenia): infections, fever; low count of blood platelet counts (thrombocytopenia): excess bruising/bleeding; increase in blast counts; disturbed sleep; and dry mouth.Citation6–Citation8 To the authors’ knowledge, there are no prior systematic reviews published evaluating the impact of disease and treatment on the HRQoL in AML patients who are not eligible for IC. The aim of this study was to conduct a SLR to determine the reported HRQoL among patients with AML receiving NIC.

Materials and methods

A SLR of evidence was conducted on HRQoL reported in patients with AML receiving NIC using matches on prespecified PICOS approach. In addition, the PRISMA was used as a guide to ensure that the current standard for systematic review methodology was met.Citation22 In this review, Embase, Medline, and the Cochrane collaboration databases were searched using the Ovid platform, covering ~10 years, from January 2007 to November 2017 to identify relevant studies reporting HRQoL and patient preference utilities and to ensure that all relevant studies included the HMA regimens used in NIC AML. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were utilized for bibliography searching to identify additional relevant studies. In addition, conference abstracts were searched to retrieve studies that had not yet been published as full-text articles and to supplement results of previously published studies. Abstracts from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, European Hematology Society, European Society of Medical Oncology, and American Society of Hematology for the period 2014–2017 were searched. The detailed search strategy is presented in Table S1. For disease, “LEUKEMIA, MYELOID”, “ACUTE/”, “LEUKEMIA, MYELOID/”, and ACUTE DISEASE/” were the MeSH terms we used. For the quality of life, we used “quality of life/” and “quality adjusted life year/” as MeSH terms.

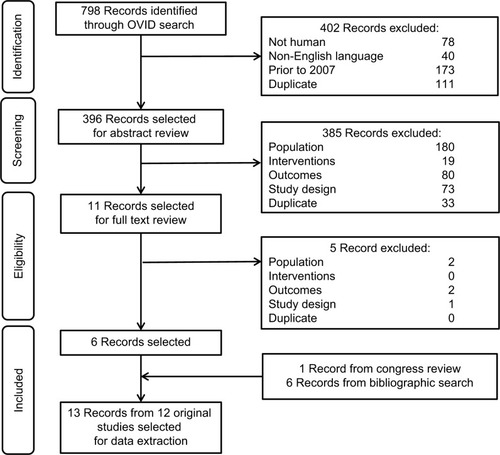

Study designs that were likely to report HRQoL and utility data for AML were included in this review. Based on the WHO AML criteria, studies on patients with RAEB-t MDS (≥20% bone marrow blast) also were included. Studies that did not have NIC AML populations and those not reporting HRQoL were excluded. Only publications written in English and published starting from January 2007 were considered since evidence older than 10 years may not be relevant as treatment practice may have changed. Shortlisted articles were initially assessed based on title and abstract. Publications not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded and listed along with the reason for study exclusion. Full-text publications were then retrieved and assessed based on the full text. Publications identified through the systematic review were evaluated in a three-step process (abstract review, full text review, and data extraction) to assess whether they should be included for data extraction. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used against the publications were developed using the PICOS format (). All steps were conducted by two independent reviewers, and any discrepancies in article selection were reassessed by a third reviewer. After the full-text review, all papers meeting inclusion criteria were retained for data extraction. Papers that were excluded in each step were listed, along with their reason for exclusion was documented for use in the PRISMA flow diagram ().

Table 1 Study eligibility criteria

The quality assessment for the HRQoL studies was assessed using the Efficace framework, which aims to determine the robustness, consistency, and relevance of such studies to support decision-making.Citation23 The search for this SLR was conducted in December 2017, and the search strategy is provided in Table S1.

Results

A total of 13 records from 12 original studies were identified, which are listed in . These included five records from four original randomized clinical trials (RCTs), three prospective studies, four patient survey studies, and one cost-effectiveness analysis reporting utility values. Ten studies utilized the EORTC QLQ-C30 and five studies reported EQ-5D values. Other scales used included HRQoL questionnaire for patients with hematological diseases (QoL-E), QoL Cancer Survivor, FACT-leukemia, FACT-fatigue, global fatigue scale, FACIT Fatigue, activities of daily living index, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The following four QLQ-C30 domains were considered most relevant: fatigue, PF, GHS, and dyspnea.Citation9 A 10-point minimally important difference threshold on a 100-point scale was assumed by the majority of studies to represent meaningful change.Citation9

Table 2 Included studies

The HRQoL results from the four original RCTs informed the reviewers that some NIC treatments achieved a meaningful improvement in the fatigue of EORTC QLQ-C30, while other patients achieved meaningful improvement in both fatigue (cycles 7 and 9) and GHS.Citation9,Citation17,Citation24–Citation26 Patients aged ≥60 years with MDS or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (intermediate 1/2, or high risk), who were ineligible for intensive treatment, showed a significant improvement in their PF and borderline improvement in GHS of EORTC QLQ-C30.Citation17

There were similar findings from HRQoL prospective studies, of which one study conducted a longitudinal, observational prospective assessment of the EORTC QLQ-C30, FACT-fatigue, EQ-5D, and global fatigue scale in patients with MDS treated with azacitidine. The results informed the reviewer that responders to therapy had significantly superior EQ-5D scores (P=0.0002) and lower scores in FACIT-fatigue (P<0.0001) vs patients who did not respond to therapy.Citation27 Another longitudinal study with MDS patients found that clinically significant improvements were achieved in the physical functioning and fatigue subscales of EORTC QLQ-C30.Citation28 The final reviewed prospective study evaluated the relationship between HRQoL and survival where it was found that HRQoL scores at diagnosis discriminated patients according to overall survival.Citation29 Patients with low scores including functional, PF, role function, and fatigue scores (<60) had shorter survival compared to those with higher scores: QOL-E functional score (median 15 weeks, 95% CI 12–17 weeks vs 55 weeks, 95% CI 42–69 weeks; P=0.002), QOL-E physical score (median 18 weeks, 95% CI 0–37 weeks vs 60 weeks, 95% CI 34–87 weeks; P=0.038), EORTC QLQ-C30 PF (median 14 weeks, 95% CI 5–24 weeks vs 60 weeks, 95% CI 44–77 weeks; P<0.0001), EORTC QLQ-C30 role function (median 21 weeks, 95% CI 7–36 weeks vs 55 weeks, 95% CI 32–79 weeks; P=0.015), and EORTC QLQ-C30 fatigue score (median 14 weeks, 95% CI 13–15 weeks vs 55 weeks, 95% CI 46–65 weeks; P=0.004).Citation29

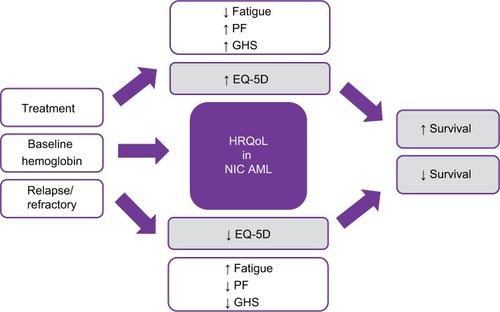

The HRQoL results from the four patient survey studies presenting the median fatigue scores of EORTC QLQ-C30 were 53.3, 66.6, and 44.3 in newly diagnosed MDS and AML patients (aged ≥60 years) receiving BSC, HMAs, and IC, respectively. The score in all patients was 53.3.Citation30 Relapsed/refractory patients were significantly more likely to be affected physically than patients with first-line disease;Citation31 the utility value for first-line patients were higher (EQ-5D =0.75) vs relapsed/refractory patients (EQ-5D =0.71) suggesting that first-line patients may have had better HRQoL scores than those on later therapies.Citation31 Fatigue and distress (followed by pain) were the symptoms reported most often among patients with AML and MDS.Citation32 According to Leunis et al,Citation14 fatigue was the most frequently reported symptom in patients with AML (78%) and other frequently reported symptoms were pain, dyspnea, insomnia, and financial difficulties. Patients with AML had significantly more problems with fatigue, pain, dyspnea, and appetite loss than the general population.Citation14 The utility value for the overall population was 0.82, patients with relapse had lower utility values vs those without a relapse (0.78 vs 0.83) and there was no much difference seen in the utility values between patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy plus hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) vs HSCT alone.Citation14 Overall, at baseline, NIC AML patients had poor HRQoL scores especially in fatigue (33) and GHS (50) on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating better health. Low baseline HRQoL scores, especially PF and fatigue (<50) were shown to be significant independent predictors of poor survival. Clinical responders demonstrated meaningful improvements in QLQ-C30 physical, role, cognitive, and social functioning, GHS, fatigue, and EQ-5D scores from baseline after being treated with chemotherapy. Clinically meaningful and significant improvements in fatigue and PF were observed with nonintensive chemotherapeutic agents across several of these studies.

The single cost-effectiveness analysis compared an HMA with conventional care regimens, including BSC, and low or standard-dose chemotherapy plus BSC in the treatment of higher risk AML with 20–30% of blasts. The utility analysis results show that, compared with patients receiving BSC, patients treated with the HMA had a better quality of life with the utility values increasing from day 0 onward to day 183, and the difference increased with increasing length of treatment; the utility values for patients treated with the HMA were 0.67 at baseline and increased to 0.80 at day 182 vs BSC with the utility value of 0.67 at baseline and increased to 0.72 at day 182.Citation33

Interestingly, we found that baseline factors such as fatigue, gender, comorbidities, bone marrow blasts, and secondary AML were not related to HRQoL in one study.Citation24 However, other studies showed these factors along with others to be correlated to HRQoL, such as baseline hemoglobin (Hg) levels and scores of QOL-E functional (r=0.0216, P=0.14), fatigue (r=0.256, P=0.002), and disease specific (r=0.247, P=0.010) were shown to be statistically correlated. Furthermore, scores from the EORTC QLQ-C30 of GHS (r=0.270, P=0.001), physical (r=0.304, P<0.0001), role (r=0.281, P=0.001), cognitive (r=0.262, P=0.003), social (r=0.229, P=0.010), functions and fatigue (r=−0.280, P=0.001), dyspnea (r=−0.287, P=0.001), and appetite loss (r=0.244, P=0.007) were statistically related to HRQoL. Age was also found to be correlated with QOL-E disease-specific scores (r=0.242, P=0.012). Finally, higher scores in HRQoL can be seen over time if transfusion dependence status is collected at the time of HRQoL assessments, displaying a possible strong HRQoL relationship between response and transfusion dependence, which could be a factor for NIC AML patients ().Citation27

Discussion

HRQoL is a multi-dimensional concept encompassing the patient’s perception of functioning and well-being. To account for this complexity, HRQoL instruments capture certain domains, at a minimum, physical, emotional, and social functioning. Collecting and publishing HRQoL data are very important to both understand the patient’s perspective and evaluate any impact or correlation of treatment that may have on a patient’s condition. Currently, there are no prior SLRs focusing on HRQoL data in NIC AML patients; therefore, the need for this information is valuable. In this SLR, we identified only 12 studies reporting HRQoL and patient preference utilities in NIC AML patients; this clearly demonstrates that there is scant published literature on the impact of disease and treatment on the HRQoL in NIC AML patients. Having an instrument that succinctly and reliably captures the impact of AML disease and treatment in the NIC AML population would help investigators incorporate HRQoL endpoints into clinical trials and help inform health care decision makers to make better treatment plans. Helping people to maintain or have improvement in HRQoL and to live longer is clearly a goal of AML therapy, even for patients not eligible for IC. Failing to understand the HRQoL implications of different treatments may mean that it could be difficult to provide this information to future AML patients facing decisions who are not eligible for IC.

Although there is scarcity of published HRQoL reported data in the NIC AML patients, from the few studies that were reviewed, we found that HRQoL was correlated with better overall survival.Citation9,Citation17,Citation26,Citation33 Survival was independently predicted by the QoL-E scores of PF when controlling for factors such as age, concomitant diseases, and treatment options.Citation29 Patients with short MDS duration had worse outcomes and was shown to be an independent adverse prognosticator.Citation17 Even though HRQoL is highly subjective, this subjectivity can be alleviated since majority of these studies were randomized controlled trials. It has become clear that the role of HRQoL in the elderly AML patients has value at diagnosis as a prognostic factor for overall survival and, thus, a potential variable that may be integrated in the process of decision-making for treatment allocation.Citation25

Understanding baseline factors can assist with individual patient treatment allocation and can provide additional information to a physician’s assessment. For example, older age, impairments in activities of daily living, Karnofsky index <80%, and HRQoL/fatigue ≥50 are likely to have poor outcomes.Citation30 Also, NIC AML patients had poor HRQoL scores (<50) on a 0–100 scale, especially in fatigue (33) and GHS (50), which were shown to be significant independent predictors of poor survival.Citation30 Prior studies, as Deschler et al, have found patient characteristics such as fatigue, PF, gender, comorbidities, bone marrow blasts, and secondary AML to be highly related to HRQoL outcomes; however, we found additional baseline HRQoL parameters to be possible independent prognostic factors in AML patients such as Hg level, age, and transfusion dependence. Including these additional baseline parameters when collecting HRQoL assessment could facilitate decision makers to assist with better treatment outcomes for NIC AML patients.

Patients diagnosed with AML are older and generally have poor prognosis. While treatment may extend overall survival for patients with AML, it may also cause significant toxicity and impairment of HRQoL;Citation17,Citation26,Citation34 therefore, using less IC agents has shown to be associated with general improvement in HRQoL in the relevant domains of fatigue, PF, and GHS.Citation14,Citation24 Other studies observed clinically meaningful and significant improvements in fatigue and PF with nonintensive chemotherapeutic agents.Citation17 These studies discussed how clinical responders demonstrated meaningful improvements in QLQ-C30 physical, role, cognitive, and social functioning, GHS, fatigue, and EQ-5D scores from baseline after being treated with nonintensive chemotherapeutic agents.

Finally, AML patients who have relapsed or become refractory to first-line treatment report worse HRQoL than those still on first-line treatments.Citation31 These observational data showed a need for effective and tolerable treatments that can maintain or improve patients’ HRQoL, especially for patients with relapsed or refractory disease. Thus, it is important to understand the impact of AML on patients receiving first-line treatment vs those who were relapsed/refractory to first-line treatment.Citation31 Although there is heterogeneity of data reporting across published studies, there is a consistent message that the HRQoL is poor, worsened by comorbidities, disease progression, or relapse in disease. Utility values and HRQoL have shown improvement with successful treatment; therefore, therapies that can help control symptom burden without negative adverse events and prevent relapses are needed.

Conclusion

HRQoL plays a crucial role in the treatment of AML patients. Currently, there are no prior SLRs conducted in evaluating HRQoL within NIC AML patients and from this SLR exercise, we found very scant literature assessing this information. Fatigue and PF at baseline have been identified as independent prognostic factors for overall survival with several studies showing improvement in both domains with treatment. Alongside the evaluation of treatment-related efficacy and safety, randomized controlled studies should also incorporate and assess the impact of treatment on patient’s PF and fatigue with the aim to improve overall HRQoL.

Author contributions

AF, CSK, and TB made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the article. TAS analyzed and interpreted the data and critically revised the article for important content. BA contributed to data interpretation and drafting of the article. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Abbreviations

| AML | = | acute myeloid leukemia |

| BSC | = | best supportive care |

| ELN | = | European LeukemiaNet |

| EORTC QLQ | = | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| EQ-5D | = | EuroQOL-5 Dimensions |

| FACIT | = | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy |

| FACT | = | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy |

| GHS | = | global health status |

| HMA | = | hypomethylating agents |

| HRQoL | = | health-related quality of life |

| IC | = | intensive chemotherapy |

| LDAC | = | low-dose cytarabine |

| MDS | = | myelodysplastic syndrome |

| NCCN | = | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| NIC | = | nonintensive chemotherapy |

| PF | = | physical function |

| PICOS | = | population, intervention, comparator, outcome and study design |

| RAEB-t | = | refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation |

| SLR | = | systematic literature review |

Acknowledgments

Parts of this study were previously published in an abstract submitted to the 2018 Congress of the European Hematology Association (https://learningcenter.ehaweb.org/eha/2018/stockholm/215952/anna.forsythe.health.related.quality.of.life.28hrqol29.in.acute.myeloid.leukemia.html). Editorial support was provided by Nazia Merritt at Purple Squirrel Economics. This study was funded by Pfizer.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Search strategy

Disclosure

TB, TAS, and BA are employees of Pfizer. AF and CSK are the employees of Purple Squirrel Economics who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the conduct of the study and development of this article. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DombretHRaffouxEGardinCAcute myeloid leukemia in the elderlySemin Oncol200835443043818692693

- JuliussonGLazarevicVHörstedtASHagbergOHöglundMSwedish Acute Leukemia Registry GroupAcute myeloid leukemia in the real world: why population-based registries are neededBlood2012119173890389922383796

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) [homepage on the Internet] Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-myeloid-leukemia/about.htmlAccessed April, 2018

- MaynadiéMDe AngelisRMarcos-GrageraRHAEMA-CARE Working GroupSurvival of European patients diagnosed with myeloid malignancies: a HAEMACARE studyHaematologica201398223023822983589

- NagelGWeberDFrommEGerman-Austrian AML Study Group (AMLSG)Epidemiological, genetic, and clinical characterization by age of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia based on an academic population-based registry study (AMLSG BiO)Ann Hematol201796121993200329090343

- KantarjianHRavandiFO’BrienSIntensive chemotherapy does not benefit most older patients (age 70 years or older) with acute myeloid leukemiaBlood2010116224422442920668231

- OhSBParkSWChungJSHematology Association of South-East Korea (HASEK) study groupTherapeutic decision-making in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: conventional intensive chemotherapy versus hypomethylating agent therapyAnn Hematol201796111801180928828639

- WalterRBOthusMBorthakurGPrediction of early death after induction therapy for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia with pretreatment risk scores: a novel paradigm for treatment assignmentJ Clin Oncol201129334417442421969499

- DombretHSeymourJFButrymAInternational phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blastsBlood2015126329129925987659

- ZiogasDCVoulgarelisMZintzarasEA network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of induction treatments in acute myeloid leukemia in the elderlyClin Ther201133325427921600383

- National Comprehensive Cancer NetworkNCCN Guidelines for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Version 2 ed Plymouth MeetingPANational Comprehensive Cancer Network2016 Available from: https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml.pdfAccessed December 20, 2018

- DöhnerHEsteyEGrimwadeDDiagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panelBlood2017129442444727895058

- WalterRBEsteyEHManagement of older or unfit patients with acute myeloid leukemiaLeukemia201529477077525005246

- LeunisARedekopWKUyl-de GrootCALöwenbergBImpaired health-related quality of life in acute myeloid leukemia survivors: a single-center studyEur J Haematol201493319820624673368

- RevickiDAOsobaDFaircloughDBarofskyIBerzonRLeidyNKRothmanMRecommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United StatesQual Life Res20009888790011284208

- EsteyEHAcute myeloid leukemia: 2013 update on risk-stratification and managementAm J Hematol2013884317327

- LübbertMSuciuSBailaLLow-dose decitabine versus best supportive care in elderly patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: final results of the randomized phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Leukemia Group and the German MDS Study GroupJ Clin Oncol201129151987199621483003

- BevansMHealth-related quality of life following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantationHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program20102010124825421239801

- EfficaceFNovikAVignettiMMandelliFCleelandCSHealth-related quality of life and symptom assessment in clinical research of patients with hematologic malignancies: where are we now and where do we go from here?Haematologica200792121596159818055981

- DeschlerBde WitteTMertelsmannRLübbertMTreatment decision-making for older patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia: problems and approachesHaematologica200691111513152217082009

- PitakoJAHaasPSvan den BoschJQuantification of outpatient management and hospitalization of patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome treated with low-dose decitabineAnn Hematol200584Suppl 12531

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaborationJ Clin Epidemiol20096210e1e3419631507

- EfficaceFBottomleyAOsobaDGotayCFlechtnerHD’haeseSZurloABeyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials-does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making?J Clin Oncol200321183502351112972527

- OlivaENSalutariPCandoniAQuality of life in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapyBlood20151262321202120

- SekeresMALancetJEWoodBLGroveLESandalicLSieversELJurcicJGRandomized phase IIb study of low-dose cytarabine and lintuzumab versus low-dose cytarabine and placebo in older adults with untreated acute myeloid leukemiaHaematologica201398111912822801961

- MindenMDombretHSeymourJFThe effect of azacitidine on health-related quality of life (HRQL) in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results from the AZA-AML-001 trialHaematologica2015221004041

- TsengEWellsRAAlibhaiSMThe effects of azacitidine on quality of life: a prospective longitudinal assessmentBlood2012120214938493823100310

- IngberSAThompsonKLamAThe effects of azacitidine on quality of life measured longitudinally in MDS patients treated at a tertiary care centerBlood20101162125712571

- OlivaENNobileFAlimenaGQuality of life in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: patients may be more accurate than physiciansHaematologica201196569670221330327

- DeschlerBIhorstGPlatzbeckerUParameters detected by geriatric and quality of life assessment in 195 older patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia are highly predictive for outcomeHaematologica201398220821622875615

- PandyaBJHadfieldAMedeirosBCQuality of life of acute myeloid leukemia patients in a real-world settingJ Clin Oncol20173515 Supple18525

- WilliamsLAAhanekuHCortesJEComparison of symptom burden in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)Blood20141242126522652

- LevyARZouDRisebroughNBucksteinRKimTBreretonNCost-effectiveness in Canada of azacitidine for the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromesCurr Oncol20142112940

- ChengMJSmithBDHouriganCSA single center survey of health-related quality of life among acute myeloid leukemia survivors in first complete remissionJ Palliat Med201720111267127328537498