Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) places a considerable burden on the US health care system, society, and individual patients due to its associated morbidity, mortality, and reduced health-related quality of life. AF increases the risk of stroke, which often results in lengthy hospital stays, increased disability, and long-term care, all of which impact medical costs. An expected increase in the prevalence of AF and incidence of AF-related stroke underscores the need for optimal management of this disorder. Although AF treatment strategies have been proven effective in clinical trials, data show that patients still receive suboptimal treatment. Adherence to AF treatment guidelines will help to optimize treatment and reduce costs due to AF-associated events; new treatments for AF show promise for future reductions in disease and cost burden due to improved tolerability profiles. Additional research is necessary to compare treatment costs and outcomes of new versus existing agents; an immediate effort to optimize treatment based on existing evidence and guidelines is critical to reducing the burden of AF.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the ineffective and uncoordinated contraction of the atria, is the most common sustained heart rhythm disturbance seen in clinical practice.Citation1,Citation2 An estimated 3.03 million Americans had AF in 2005, and the prevalence is expected to rise to 7.56 million by 2050.Citation3 Between 1985 and 1999, the number of hospitalizations with AF as a principal diagnosis increased by 144% according to the National Hospital Discharge Survey.Citation4 These numbers are probably even greater, since arrhythmias represented 10.6% of patients with a principal diagnosis related to the circulatory system.Citation5 Research demonstrates a potential link between AF and atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension, chronic inflammation, and metabolic syndrome.Citation6 AF is also associated with substantial morbidity (stroke, heart failure), mortality, and poor health-related quality of life.Citation7–Citation14 Based on these issues, AF imposes a considerable cost burden on the patient, the health care system, and society.Citation15–Citation17

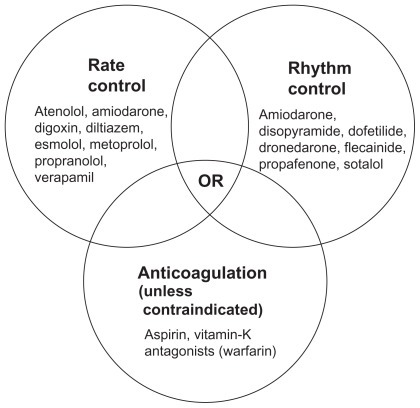

AF treatment is complex. Comprehensive management of the patient with AF requires a multifaceted approach directed at first identifying any underlying, reversible, treatable causes,Citation18 and then controlling symptoms and protecting the patient from central and peripheral embolism.Citation19,Citation20 The American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, and Heart Rhythm Society (ACCF/AHA/HRS) task force recommend that AF management involve three nonmutually exclusive objectives: rate control, prevention of thromboembolism, and correction of the rhythm disturbance ().Citation19 The initial management decision is either a rate-control or rhythm-control strategy. Using the rate-control strategy, the ventricular rate is controlled with no commitment to restore or maintain sinus rhythm, unlike the rhythm-control strategy, which attempts restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm.Citation19

Figure 1 AF treatment. Drugs are listed alphabetically.Citation19

Anticoagulation therapy is to be considered regardless of which rate or rhythm control therapy is prescribed, because current agents used for rate and rhythm control do not reduce stroke risk and cannot be substituted for antithrombotic treatment.Citation21,Citation22 The CHADSCitation2 scoring system, which utilizes age and comorbid conditions to stratify a patient’s stroke risk, is recommended to aid in the decision to use antithrombotic therapy ().Citation19,Citation23 Despite the guidelines, AF may be managed suboptimally due to the complexity of treatment. It has been shown that compliance with some antiarrhythmic agents is poor and patients who discontinue treatment are unlikely to restart therapy.Citation24 Suboptimal management of AF could result in a delay in reverting the patient to normal sinus rhythm, which in turn could promote atrial remodeling, making future sinus rhythm maintenance difficult.Citation25 This article discusses the clinical consequences and associated costs of suboptimal management of AF in the United States (US), as well as treatment strategies that may reduce the burden of AF and improve patient outcomes.

Table 1 CHADS2 index stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular AF not treated with anticoagulation and recommended antithrombotic therapy by risk factorsTable Footnotea

Overall economic burden of AF in the US

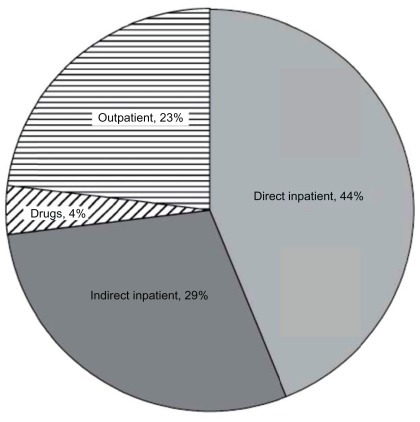

Although there are numerous cost-comparison studies of different AF treatments, there are few US-based direct cost assessments of AF treatments. A recent national survey estimated that direct medical costs were 73% higher in patients with AF compared with matched control subjects, representing a net incremental cost of $8705 per patient per year and a national incremental cost between $6.0 and $26.0 billion (2008 US dollars [USD]).Citation26 A 2001 study found that approximately 234,000 hospital outpatient department visits, 276,000 emergency room visits, 350,000 hospitalizations, and 5 million office visits were attributable annually to AF.Citation15 It has been shown that in the year following index hospitalization, 12.5% of chronic AF patients and 10.1% of newly diagnosed AF patients are readmitted for AF.Citation27 The total annual medical cost for the treatment of AF in the inpatient, emergency department, and hospital outpatient settings was estimated at $6.65 billion (2005 USD; inflation-adjusted to 7.71 billion 2011 USD) (), and is likely an underestimate as costs for long-term anticoagulation, stroke prevention, inpatient drugs, and hospital-based physician services were not included.Citation15 This assessment included billed hospital charges and costs of procedures for which AF was the principal discharge diagnosis ($2.93 billion), incremental inpatient costs due to AF as a comorbid diagnosis ($1.95 billion), and physician fees, drugs, procedures, and facility costs for ambulatory/outpatient treatment of AF ($1.76 billion).Citation15

Figure 2 Distribution of total medical costs for treating AF in the United States (2005).

Copyright© 2006, John Wiley and Sons. Reprinted with permission from Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, Mercader M, Reynolds M, Zimetbaum P. Assessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health. 2006;9(5):348–356.Citation15

One study estimated the direct and indirect costs of AF (2002 USD) in a privately insured US population aged <65 years. The direct annual cost of AF was $15,553 per patient compared with $3204 for enrollees without AF. These costs were adjusted to $19,575 and $4809 in 2011 USD.Citation16 Indirect costs (ie, disability claims and absenteeism) were $2134 higher annually for AF patients compared with enrollees without AF ($2847 [$3583 2011 USD] vs $713 [$897 2011 USD], respectively). Regarding patients aged >65 years, a Medicare database study found that the adjusted mean incremental treatment cost of AF was $14,199 (2004 USD; $17,019 2011 USD) in patients diagnosed with AF and followed for 1 year.Citation17 Some of this cost was attributable to the incidence of stroke and heart failure 1 year after diagnosis.Citation17 In another study, inpatient costs were $11,307 (2006 USD; $12,699 2011 USD) and outpatient costs were $2827 ($3175 2011 USD) for primary AF hospitalization; for hospitalized patients with secondary AF, AF-related inpatient costs were $5181 ($5819 2011 USD) and outpatient costs were $1376 ($1545 2011 USD).Citation28 contains recently published data on direct health care costs attributable to an AF diagnosis, including cost adjustments to 2011 USD (differing costs may reflect variations in study designs and data sets).Citation28–Citation30

Table 2 Recently published AF health care costs

Inpatient drug initiation and costs of adverse events and adverse-event monitoring significantly add to the overall economic burden of AF treatment. A recent analysis examined the costs associated with initiating sotalol and dofetilide in the inpatient setting.Citation31 Treatment guidelines recommend inpatient initiation of dofetilide, while the initiation of sotalol is mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with a recommended minimum hospital stay of 3 days to assess for ventricular proarrhythmia.Citation19,Citation32,Citation33 Mean total inpatient costs per patient were $3278 in the sotalol group and $3610 in the dofetilide group (2007 USD; $3580 and $3942 2011 USD, respectively). The greatest costs were for room and board followed by cardiology/electrocardiograms.Citation31 The incidence and cost of suspected adverse events and adverse-event monitoring during AF rhythm control and/or rate-control therapy was also high.Citation34 Overall, 50.1% of treated patients had a suspected adverse event and/or function test for adverse-event monitoring (45.5% with rate control, 53.5% with rhythm control, and 61.2% with combined rhythm/rate control). The mean cost of adverse events and adverse-event monitoring among treated patients was $3089 per patient (2006 USD; $3469 2011 USD).Citation34

Cost of stroke in patients with AF

Stroke is a leading cause of death in the world and a leading cause of morbidity in adults aged >60 years.Citation35 AF independently increases the risk of ischemic stroke by four- to fivefold.Citation36 In the absence of antithrombotic therapy, the annual risk of stroke in patients with AF (with risk factors including history of hypertension, diabetes, and history of prior stroke/transient ischemic attack [TIA]) is 4.9% in patients aged <65 years and 8.1% in patients aged >75 years.Citation37 Because the prevalence of AF increases with age and older age confers an increased risk of stroke, the proportion of strokes attributable to AF increases with age.Citation37

Stroke is associated with substantial inpatient and long-term costs.Citation38 A review of published data on AF prevalence found that survivors of AF-related stroke were more likely to have longer hospital stays, disability, and need for long-term care, all of which increase health care costs.Citation39 A review of 14 studies found that patients with AF-related stroke had worse outcomes than patients with non-AF-related stroke, including higher mortality, severity, recurrence, functional impairment, and dependency.Citation40 A retrospective chart review showed that patients with AF-associated ischemic stroke were 2.23 times more likely to be bedridden than patients who had strokes from other causes.Citation41 Importantly, previously diagnosed AF patients in this chart review were not receiving therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of their stroke.Citation41

A recent retrospective observational cohort study utilized medical and pharmacy claims from a managed care organization to identify continuously benefit-eligible AF patients without prior valvular disease or warfarin use between 2000 and 2002 (costs adjusted to 2004 USD).Citation42 All patients were followed for at least 6 months, until plan termination or the end of study follow-up. Stroke risk was assessed using the CHADS2 index. Inpatient and outpatient cost benchmarks were utilized to estimate total direct health care costs (pre- and post-AF index claim). Total direct health care costs were also assessed for patients with TIA, ischemic stroke (IS), and major bleed (MB). Pre- versus post-AF diagnosis total direct health care costs were $412 and $1235 per member per month (pmpm), respectively ($494 and $1480 2011 USD, respectively). Of the 448 (12%) patients with a TIA, IS, or MB, pmpm costs post-AF diagnosis ranged from $2235 to $3135 ($2679–$3758 2011 USD) correlating with CHADS2 stroke-risk status and exposure to warfarin. Total cohort pmpm costs pre- and post-event increased 24% from $3447 to $4262 ($4132–$5109 2011 USD).Citation42

Cost benefits of optimal anticoagulation

In the US, increasing rates of AF-related stroke due to the aging population will come at a high cost to society given the overlap between AF-attributable stroke and the age of Medicare eligibility. The need for optimal anticoagulation was demonstrated in a pooled analysis of five large, randomized, controlled AF antithrombotic trials, which showed that warfarin reduced the frequency of all strokes by 68% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 50%–79%); the efficacy of aspirin was less consistent.Citation37 A conservative economic model estimated a Medicare saving of $1.14 billion annually (2003 USD; $1.4 billion 2011 USD) through maintaining patients eligible for anticoagulation on therapeutic doses of warfarin.Citation43 Depending on the study population, anticoagulant therapy has been shown to decrease the risk of stroke by 42% to 86%.Citation44

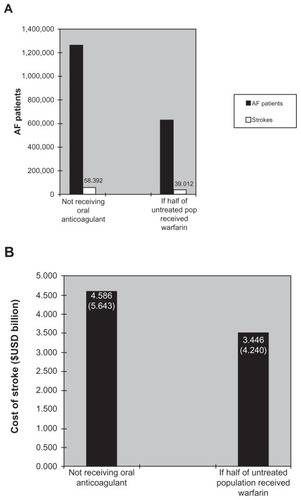

Although several randomized clinical trials have documented the benefits of warfarin in preventing AF-related stroke, a growing body of evidence indicates that anticoagulants are routinely underutilized for stroke prevention in patients with AF.Citation45,Citation46 It has been estimated that half of the patients receiving warfarin do not receive the appropriate anticoagulant therapy.Citation44 Anticoagulant therapy with warfarin has a narrow therapeutic index requiring coagulation monitoring by a physician or, in some cases, pharmacists and nurses;Citation47,Citation48 this requirement, along with the inherent properties of warfarin related to its bleeding risk, may contribute to its low levels of utilization.Citation45 A comparative study between usual medical care and a clinical pharmacistrun anticoagulation clinic showed that pharmacist supervision improved anticoagulation control, reduced bleeding and thromboembolic event rates, and saved $162,058 per 100 patients annually (1998 USD; $225,112 2011 USD) in reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.Citation49 presents a disease model showing the effects of suboptimal versus optimal oral anticoagulation on stroke rates. The economic model considers a stable population of patients with AF, such as that which might be found in a managed care organization or a state’s Medicare group; it allows for movement of individuals with AF in and out of the population during the course of a year. Scenarios are created (eg, “if half of all those who currently do not receive anticoagulation were to receive well-controlled warfarin”) to represent the current situation in the population of interest compared with other potential scenarios of care. According to this model, stroke rates and associated costs could decrease dramatically if 50% of warfarin-eligible patients were optimally coagulated. Approximately 1.265 million patients currently not receiving prophylaxis suffer over 58,000 strokes annually. If half of those not receiving warfarin were optimally anticoagulated, approximately 19,000 strokes would be prevented.Citation43

Figure 3 Model results: (A) reductions in AF-related stroke based upon half of untreated patients receiving warfarin and (B) cost of stroke.Citation43 The economic model considers a stable population of patients with AF, such as that which might be found in a managed care organization or a state’s Medicare group.

Abbreviation: AF, atrial fibrillation.

Warfarin therapy is monitored to ensure that patients remain within the target international normalized ratio (INR) range of 2.0 to 3.0. Studies of the quality of anticoagulation management in patients with AF found that up to 60% of patients receiving warfarin have INR outside the recommended therapeutic target range.Citation50–Citation52 It is likely that these studies can be generalized to the US population as they included AF patients in a range of settings (emergency department, long-term care, and community); one can therefore conclude that the majority of patients with an AF diagnosis in the US are not optimally treated with anticoagulant therapies. Such suboptimal therapy places patients at risk for complications and further management expenditures.Citation53

One real-world study estimated the cost effectiveness of different warfarin treatment scenarios.Citation53 A semi-Markov transition model (11 primary health states with four additional states representing temporary discontinuation of therapy) was designed due to the chronic nature of AF and its treatment and the varying but continuous risk of stroke and hemorrhage. The scenarios included in the model were: (1) perfect warfarin control (100% of patients within target INR and following guideline recommendationsCitation19,Citation54 for ideal treatment goal); (2) trial-like warfarin control (clinical trial conditions; INRs within target 68% of the time as reported in the Stroke Prevention by ORal Thrombin Inhibitor in atrial Fibrillation [SPORTIF] V trial);Citation55 (3) “real-world” warfarin control (routine clinical practice conditions; INRs within target 48% of the time based on data from a retrospective study of US outpatient physician practices);Citation56 and (4) real-world prescription (and control) of warfarin, aspirin, or neither for warfarin-eligible patients at moderate-to-high risk of stroke (routine clinical practice conditions, in which a proportion of warfarin-eligible patients were prescribed either aspirin [12%] or neither warfarin nor aspirin [23%]).Citation56 The total number of primary and recurrent ischemic strokes in a cohort of 1000 patients (age 70 years) was assessed, and the model showed increased numbers of strokes as real-world conditions increased and trial-like management declined. Both clinical and cost outcomes were found to be dependent on the quality of anticoagulation ().

Table 3 Results of a cost-effectiveness model predicting clinical trial versus “real-world” warfarin usage for AF-related stroke preventionCitation53

In another cost-effectiveness semi-Markov decision analysis model of patients with AF, the lifetime cost per patient for anticoagulation using a monitoring service was found to be $8661 versus $10,746 for usual care (2004 USD; $10,381 vs $12,880 2011 USD).Citation57 The model predicted that anticoagulation services improved the effectiveness (measured in quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs]) and reduced costs (estimated at $2100; $2517 2011 USD), and was therefore superior to usual care.

In terms of the cost of MB events with warfarin use, a recent database study of warfarin-treated patients with AF found that MB events associated with warfarin therapy, although nearly twice as costly compared with patients without MB events, were relatively rare; among 47,437 total patients, only 194 (0.4%) had intracranial MB events and 919 (1.9%) experienced gastrointestinal MB events.Citation58

In addition to warfarin and other anticoagulants (eg, unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin), direct thrombin inhibitors represent a newer class of anticoagulants.Citation59 Newer antithrombotic agents include rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran, which are selective for specific coagulation factors such as factor Xa and thrombin. Citation60–Citation62 Advantages shared by these newer anticoagulants over existing antithrombotic agents consist of selective targeting for a single coagulation factor, rapid onset of action, fewer drug interactions, and no required dosage adjustment according to patient age, gender, body weight, or mild renal impairment.Citation62 Clinical trials with these new anticoagulants in patients with AF include ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban vs warfarin), ARISTOTLE (apixaban vs warfarin) and AVERROES (apixaban vs aspirin in patients unsuitable for warfarin). The ROCKET-AF trial showed that rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin with regard to stroke or systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular AF.Citation63 Rivaroxaban is approved by the FDA for the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF.Citation64 In the AVERROES study, apixaban reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism without significantly increasing major bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage, Citation65 while the ARISTOTLE study demonstrated that apixaban was superior to warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism.Citation66 An important limitation to the use of these agents is the lack of readily available reversal agents or antidotes.

Dabigatran is a novel oral direct thrombin inhibitor that is approved in the US (October 2010) to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with AF.Citation67 In the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial, two fixed doses of dabigatran (110 and 150 mg, administered in a blinded fashion) were compared with open-label use of warfarin in patients with AF and an increased risk for stroke.Citation68,Citation69 After a follow-up of 2 years, the primary endpoint of stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 182 patients in the dabigatran 110 mg group (1.53%/year), 134 patients in the dabigatran 150 mg group (1.11%/year), and 199 patients in the warfarin group (1.69%/year). Both dabigatran doses were found to be noninferior to warfarin (P < 0.001), and the dabigatran 150-mg dose was found to be superior to warfarin (P < 0.001). Hemorrhagic stroke rates were 0.38% per year in the warfarin group versus 0.12% per year in the dabigatran 110 mg group and 0.10% per year in the dabigatran 150 mg group (P < 0.001, both comparisons). This decrease in the number of strokes with dabigatran may decrease the costs and economic burden associated with stroke. The 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines recommend dabigatran as an alternative to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic thromboembolism in patients who have paroxysmal to permanent AF and risk factors for stroke/systemic embolization and who do not have a prosthetic heart valve, hemodynamically significant valve disease, severe renal failure, or advanced liver disease.Citation70

Cost effectiveness of treatment strategies for AF

The Fibrillation Registry Assessing Costs, Therapies, Adverse Events, and Lifestyle (FRACTAL) study showed that patients with AF who are managed with cardioversion and pharmacotherapy incur AF- and cardiovascular-related health care costs of $4000 to $5000 per year (2002 USD; $5034–$6293 2011 USD).Citation71 AF-related health care costs averaged $4700 ($5915 2011 USD) per patient per year during the first few years following diagnosis,Citation71 but subsequent annual costs varied greatly according to the AF clinical course, with hospital care contributing the largest and most variable component of total cost. Among patients with recurrent AF, the frequency of recurrence was strongly associated with higher resource utilization, with each recurrence increasing annual costs by an average of $1600 (2002 USD; $2014 2011 USD).Citation71 Several recent studies comparing rate and rhythm control strategies have found no meaningful differences in terms of mortality from cardiovascular causes and stroke.Citation8,Citation21,Citation72–Citation75 Additionally, drivers of cost in patients with AF are not fully elucidated.

A post-hoc cost-effectiveness analysis from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) study was published shortly after the FRACTAL study and demonstrated that patients randomized to pharmacologic rate control had less resource utilization and lower costs than patients randomized to rhythm control (cost savings range, $2189–$5481 per patient, 2002 USD; $2755–$6898 2011 USD).Citation76 Another post-hoc analysis of AFFIRM clinical treatment data suggested that the benefits of rhythm control may have been offset by the adverse effects of antiarrhythmic therapy, specifically amiodarone, which was used for rhythm control in the study.Citation77 Whether these AFFIRM cost data would be affected if different antiarrhythmic agents (with better adverse-effect profiles than amiodarone) were analyzed in the model is unknown; however, as the adverse effects had considerable influence over the cost model, cost data can be expected to be affected.Citation77

Newer anticoagulants and antiarrhythmic agents may present cost savings compared with older treatments. In an analysis including patients aged ≥65 years with AF who were at increased risk of stroke, dabigatran was shown to be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin.Citation78 The analysis estimated a cost of $45,372 per QALY (2008 USD; $47,715 2011 USD) gained with high-dose dabigatran (150 mg twice daily) compared with warfarin.Citation78 Another study compared the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran 150 mg twice daily with warfarin, employing a Markov decision-analysis model in a hypothetical cohort of 70-year-old patients with AF and a cost-effectiveness threshold of $50,000/QALY.Citation79 The analysis found dabigatran to be cost-effective in AF populations at high risk of hemorrhage or stroke (CHADS2 score ≥ 3) and warfarin to be cost-effective in moderate-risk AF populations (CHADS2 score 1 or 2). Dabigatran was cost-effective for patients with a CHADS2 score of 2 only if they were at a high risk of major hemorrhage or had poor INR control with warfarin.Citation79 In a separate cost-effectiveness analysis employing a Markov decision-analysis model in a hypothetical cohort of 70-year-old patients with AF and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, dabigatran provided 0.36 additional QALYs versus warfarin at a cost of $9000 (2010 USD; $9314 2011 USD), yielding an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $25,000 ($25,873 2011 USD). However, dabigatran was not cost-effective if its relative risk of stroke compared with warfarin exceeded 0.92.Citation80 Lastly, in a cost-effectiveness analysis in the United Kingdom of simulated patients at moderate-to-high risk of stroke with a mean baseline CHADS2 score of 2, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was associated with positive incremental net benefits versus warfarin, but was unlikely to be cost-effective in clinics able to achieve good INR control with warfarin.Citation81

Given the 24% relative reduction in hospitalizations demonstrated with dronedarone use in the A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Parallel Arm Trial to Assess the Efficacy of Dronedarone 400 mg bid for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Hospitalization or Death from any Cause in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation/Atrial Flutter (ATHENA) trial,Citation82 this agent has the potential to reduce costs in patients with AF. One retrospective study analyzed the incidence and direct costs of ATHENA-type outcomes in 15,552 patients with AF who were covered by Medicare supplemental insurance from 2004 to 2007.Citation83 Mean hospitalization cost per patient was $11,085 (2006 USD; $12,450 2011 USD). Mean costs per patient varied from $7476 (mean cost per hospitalization for AF/supraventricular rhythm disorder [primary diagnosis, nonfatal]) to $37,067 (mean hospitalization cost per death, cardiovascular transcutaneous intervention procedure, or cardiovascular surgical intervention) ($8396 to $41,631, respectively, 2011 USD).Citation83 Novel antiarrhythmic therapies such as dronedarone, with the potential to reduce cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality in similar patients, could decrease health care costs.

New antiarrhythmic agents for the treatment of AF

Data demonstrate limited efficacy and partially deleterious adverse-effect profiles for conventional antiarrhythmic agents for AF.Citation84 Antiarrhythmic agents that have atrial-selective actions and target multiple ion channels may be more tolerable and free of proarrhythmic effects.Citation85 New agents (ie, dronedarone and vernakalant) offer promise in optimizing the management of AF by potentially reducing AF burden and costs through more favorable tolerability profiles.

Dronedarone

Dronedarone, a noniodinated benzofuran derivative, is a recently (2009) approved multichannel antiarrhythmic agent. Dronedarone is indicated in the US to reduce the risk of hospitalization for AF in patients in sinus rhythm with a history of paroxysmal or persistent AF.Citation86 According to the 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS guidelines, dronedarone is recommended as first-line therapy in patients with AF who have no or minimal heart disease, hypertension without left ventricular hypertrophy, or coronary heart disease (class IIa recommendation).Citation70 In the ATHENA trial, dronedarone demonstrated a significant risk reduction (24%, P < 0.001) in hospitalizations due to cardiovascular events or deaths from any cause compared with placebo in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF/AFL.Citation82 In an analysis of stroke in the ATHENA trial, dronedarone reduced the risk of stroke from 1.8% per year to 1.2% per year (P = 0.027).Citation87 In the Efficacy and Safety of Dronedarone for the Control of Ventricular Rate During Atrial Fibrillation (ERATO) study, dronedarone was found to control ventricular rate in patients diagnosed with permanent AF already treated with standard therapies.Citation88

Dronedarone was demonstrated to be effective in maintaining sinus rhythm in The European Trial in Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter Patients Receiving Dronedarone for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm (EURIDIS) study and the American–Australian–African Trial with Dronedarone in Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter Patients for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm (ADONIS) study.Citation89 The most common adverse events seen with dronedarone include gastrointestinal problems including diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain.Citation82,Citation88–Citation91 Dronedarone is contraindicated in patients with symptomatic heart failure with recent decompensation requiring hospitalization or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV heart failure and in patients with AF who will not or cannot be cardioverted into normal sinus rhythm.Citation86

The PALLAS study, a trial assessing potential cardiovascular outcomes in patients with permanent AF, was prematurely terminated due to increased adverse cardiovascular events in the dronedarone arm.Citation92 There were 25 deaths in the dronedarone group (21 from cardiovascular causes) and 13 in the placebo group (10 from cardiovascular causes) (P = 0.046). The coprimary outcome, a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, or death from cardiovascular causes, occurred in 43 patients receiving dronedarone and 19 patients receiving placebo (P = 0.002). These data indicate that dronedarone should not be used in patients with permanent AF who are at risk for major vascular events.Citation92

There have been several postmarketing reports of hepatocellular liver injury and hepatic failure in patients receiving dronedarone, including two reports of acute hepatic failure that required transplantation and new-onset or worsening heart failure.Citation93,Citation94 Obtaining periodic hepatic serum enzymes, especially during the first 6 months of treatment with dronedarone, is recommended.Citation86 Postmarketing cases of increased INR with or without bleeding events have also been reported in patients on warfarin initiated on dronedarone.Citation86,Citation95 Postmarketing cases of interstitial lung disease including pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis have also been reported.Citation86 Exposure to dabigatran is also higher when it is administered with dronedarone than when it is administered alone.Citation86

The US FDA recently completed a safety review of dronedarone based on data from the PALLAS and ATHENA trials. This review showed that dronedarone increased the risk of serious cardiovascular events, including death, when used by patients with permanent AF.Citation96 The prescribing information for dronedarone has been revised to include recommendations from the FDA regarding the use of dronedarone to manage the potential serious cardiovascular risks with the drug.Citation86,Citation96 These recommendations include: dronedarone should not be used in patients with AF who cannot or will not be converted into normal sinus rhythm (permanent AF); heart rate should be monitored by electrocardiogram at least once every 3 months, and if the patient is in AF, dronedarone should be stopped or, if clinically indicated, the patient should be cardioverted; dronedarone is indicated to reduce hospitalization for AF in patients in sinus rhythm with a history of nonpermanent AF (known as paroxysmal or persistent AF); and patients taking dronedarone should receive appropriate antithrombotic therapy.Citation86,Citation96

Vernakalant

Intravenous vernakalant, a sodium and potassium channel blocker with atrial-selective action, is approved in the European Union, Iceland, and Norway for the rapid conversion of recent-onset AF to sinus rhythm in adult nonsurgery patients with AF of ≤7 days duration and for adult post-cardiac surgery patients with AF of ≤3 days duration.Citation97 In the AVRO study, intravenous vernakalant was more effective than amiodarone for acute conversion of recent- onset AF.Citation98 For the oral formulation, early phase II studies demonstrated that oral vernakalant successfully maintained sinus rhythm compared with placebo, and no proarrhythmias relating to vernakalant have been reported to date.Citation99 There were also no serious adverse events related to vernakalant in phase II trials.Citation100 Vernakalant was found to be an effective agent for conversion to normal sinus rhythm in patients with recent-onset AF.Citation99 In a review of six early-phase clinical trials, vernakalant rapidly and effectively terminated recentonset AF and was found to be well tolerated and efficacious at AF conversion in patients with postoperative AF.Citation99 Further studies are warranted to better define the role of vernakalant in the management of AF in order to determine whether its benefits translate into a decreased cost burden.

Catheter ablation

For AF patients whose symptoms are not well controlled with pharmacologic therapy, catheter ablation is an increasingly used treatment option. According to the 2011ACCF/AHA/HRS guideline update, catheter ablation may be useful to maintain sinus rhythm in selected patients with significantly symptomatic, paroxysmal AF who have failed treatment with an antiarrhythmic agent and have normal or mildly dilated left atria, normal or mildly reduced left ventricular function, and no severe pulmonary disease (class I recommendation upgraded from class IIa, but remaining a class IIa recommendation in both Europe and Canada); to treat symptomatic persistent AF (class IIa recommendation); and to treat symptomatic paroxysmal AF in patients with significant left atrial dilatation or with significant left ventricular dysfunction (class IIb recommendation).Citation70 Recent studies have reported that catheter ablation successfully treats paroxysmal AF in >80% of cases and persistent AF in >70% of cases.Citation101 However, catheter ablation is associated with major complications (reported in about 6% of procedures) such as pulmonary vein stenosis, thromboembolism, atrioesophageal fistula, and left atrial flutter.Citation19,Citation102

The cost-effectiveness of catheter ablation is difficult to determine due to a number of factors, including differences in the experience levels of centers, use of technology, and rates of reimbursement, which affect cost calculations.Citation101 Studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of AF ablation compared with rhythm control or antiarrhythmic agents have shown that ablation treatment results in improved quality-adjusted life expectancy, but at a higher cost.Citation103–Citation105

Conclusion

Recent data present a compelling picture of the burden of AF on the US health care system and society. As the US population ages and the prevalence of AF increases, it is clear that AF management strategies need to be optimal. Suboptimal management of AF places patients at risk for AF-associated stroke, the most costly AF-associated event. Numerous studies demonstrate the efficacy of anticoagulation in reducing the risk of AF-related embolic events and preventing hospitalizations, but efficacy is compromised by inadequate and suboptimal treatment patterns. Therapeutic strategies such as rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation provide cost-effective means to optimally manage the patient with AF, as do treatment options such as new antiarrhythmic agents or catheter ablation. Given that nearly 75% of the total costs associated with AF are attributed to direct and indirect hospitalization costs,Citation15 clinical strategies that can reduce AF-related hospitalizations may optimize care by improving clinical outcomes and reducing costs. Further research is necessary to compare new antiarrhythmic agents with existing therapies to assess clinical and economic differences in real-world settings.

Acknowledgments/Disclosure

Editorial support for this article was provided by Vrinda Mahajan, PharmD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC. Editorial support for this article was funded by sanofi-aventis US. The opinions expressed in the current article are those of the author. The author received no honoraria or other form of financial support related to the development of this manuscript.

References

- BajpaiASavelievaICammAJEpidemiology and economic burden of atrial fibrillationTouch Briefings20071417

- DorianPMangatIPinterAKorleyVThe burden of atrial fibrillation: should we abandon antiarrhythmic drug therapy?J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther20049425726215678244

- NaccarelliGVVarkerHLinJSchulmanKLIncreasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United StatesAm J Cardiol2009104111534153919932788

- WattigneyWAMensahGACroftJBIncreasing trends in hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 1985 through 1999: implications for primary preventionCirculation2003108671171612885749

- BialyDHospitalization for arrhythmias in the United States: Importance of atrial fibrillation [abstract 716–714]J Am Coll Cardiol199219341A

- WyseDGGershBJAtrial fibrillation: a perspective: thinking inside and outside the boxCirculation2004109253089309515226225

- ChatapGGiraudKVincentJPAtrial fibrillation in the elderly: facts and managementDrugs Aging2002191181984612428993

- HagensVERanchorAVVan SonderenEEffect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) StudyJ Am Coll Cardiol200443224124714736444

- DorianPJungWNewmanDThe impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation: implications for the assessment of investigational therapyJ Am Coll Cardiol20003641303130911028487

- PaquetteMRoyDTalajicMRole of gender and personality on quality-of-life impairment in intermittent atrial fibrillationAm J Cardiol200086776476811018197

- KannelWBAbbottRDSavageDDMcNamaraPMEpidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham studyN Engl J Med198230617101810227062992

- WattigneyWAMensahGACroftJBIncreased atrial fibrillation mortality: United States, 1980–1998Am J Epidemiol2002155981982611978585

- Atrial fibrillation as a contributing cause of death and Medicare hospitalization – United States, 1999MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep200352712813012813112617537

- SinghSNTangXCSinghBNQuality of life and exercise performance in patients in sinus rhythm versus persistent atrial fibrillation: a Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program SubstudyJ Am Coll Cardiol200648472173016904540

- CoyneKSParamoreCGrandySMercaderMReynoldsMZimetbaumPAssessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United StatesValue Health20069534835616961553

- WuEQBirnbaumHGMarevaMEconomic burden and co-morbidities of atrial fibrillation in a privately insured populationCurr Med Res Opin200521101693169916238910

- LeeWCLamasGABaluSSpaldingJWangQPashosCLDirect treatment cost of atrial fibrillation in the elderly American population: a Medicare perspectiveJ Med Econ200811228129819450086

- AnisRRRole of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in the management of atrial fibrillationExp Clin Cardiol2009141e1e719492029

- FusterVRydenLECannomDS2011ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Updates Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm SocietyJ Am Coll Cardiol20115711e101e19821392637

- TengMPCatherwoodLEMelbyDPCost effectiveness of therapies for atrial fibrillation. A reviewPharmacoeconomics200018431733315344302

- WyseDGWaldoALDiMarcoJPA comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2002347231825183312466506

- BushnellCDMatcharDBPharmacoeconomics of atrial fibrillation and stroke preventionAm J Manag Care200410Suppl 3S66S7115152748

- GageBFWatermanADShannonWBoechlerMRichMWRadfordMJValidation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial FibrillationJAMA2001285222864287011401607

- IshakKJProskorovskyIGuoSLinJPersistence with antiarrhythmics and the impact on atrial fibrillation-related outcomesAm J Pharm Benefits200914193200

- NaccarelliGVDell’OrfanoJTWolbretteDLPatelHMLuckJCCost-effective management of acute atrial fibrillation: role of rate control, spontaneous conversion, medical and direct current cardioversion, transesophageal echocardiography, and antiembolic therapyAm J Cardiol20008510A36D45D

- KimMHJohnstonSSChuBCDalalMRSchulmanKLEstimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United StatesCirc Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes20114331332021540439

- KimMHLinJHusseinMBattlemanDIncidence and temporal pattern of hospital readmissions for patients with atrial fibrillationCurr Med Res Opin20092551215122019327101

- KimMHLinJHusseinMKreilickCBattlemanDCost of atrial fibrillation in United States managed care organizationsAdv Ther200926911119129998

- PatelPPJohnstonSJLinJSchulmanKLNaccarelliGVCost burden of hospitalization and mortality in United States atrial fibrillation/flutter patients [abstract PO03-53]Presented at: Heart Rhythm 2009May 13–16, 2009Boston, MA

- KimMHKlingmanDLinJBattlemanDSPatterns and predictors of discontinuation of rhythm-control drug therapy in patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillationPharmacotherapy200929121417142619947801

- KimMHKlingmanDLinJPathakPBattlemanDSCost of hospital admission for antiarrhythmic drug initiation in atrial fibrillationAnn Pharmacother200943584084819417111

- Berlex LaboratoriesBetapace [package insert]Wayne, NJBerlex Laboratories, Inc2010

- PfizerTikosyn [package insert]New York, NYPfizer Labs2006

- KimMHLinJHusseinMBattlemanDIncidence and economic burden of suspected adverse events and adverse event monitoring during AF therapyCurr Med Res Opin200925123037304719852699

- World Health OrganizationShaping the Future The World Health Report 2003Geneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization20031204

- WolfPAAbbottRDKannelWBAtrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham StudyStroke19912289839881866765

- The Atrial Fibrillation InvestigatorsRisk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trialsArch Intern Med199415413144914578018000

- SzucsTDBramkampMPharmacoeconomics of anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a reviewJ Thromb Haemost2006461180118516706956

- RyderKMBenjaminEJEpidemiology and significance of atrial fibrillationAm J Cardiol1999849A131R138R

- MillerPSAnderssonFLKalraLAre cost benefits of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation underestimated?Stroke200536236036615637326

- DulliDAStankoHLevineRLAtrial fibrillation is associated with severe acute ischemic strokeNeuroepidemiology200322211812312629277

- BoccuzziSJMartinJStephensonJRetrospective study of total healthcare costs associated with chronic nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and the occurrence of a first transient ischemic attack, stroke or major bleedCurr Med Res Opin200925122853286419916729

- CaroJJAn economic model of stroke in atrial fibrillation: the cost of suboptimal oral anticoagulationAm J Manag Care200410Suppl 14S451S45815696909

- EzekowitzMDFalkRHThe increasing need for anticoagulant therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillationMayo Clin Proc200479790491315244388

- WittkowskyAKEffective anticoagulation therapy: defining the gap between clinical studies and clinical practiceAm J Manag Care200410Suppl 10S297S30615605700

- ThosaniAJXiongYLinJKothawalaPZimetbaumPJAre atrial fibrillation patients receiving anticoagulation in accordance with their stroke risk? [abstract PO06-60]Presented at: Heart Rhythm 2009May 13–16, 2009Boston, MA

- DamaskeDLBairdRWDevelopment and implementation of a pharmacist-managed inpatient warfarin protocolProc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)200518439740016252031

- NYSED.govPractice Alerts and Guidelines: Coumadin (Warfarin) Managed Dosing by NursesJune 252009New York State Education Department Office of the Professions Available from: http://www.op.nysed.gov/prof/nurse/nurse-coumadin.htmAccessed December 12, 2011

- ChiquetteEAmatoMGBusseyHIComparison of an anticoagulation clinic with usual medical care: anticoagulation control, patient outcomes, and health care costsArch Intern Med199815815164116479701098

- ScottPAPancioliAMDavisLAFrederiksenSMEckmanJPrevalence of atrial fibrillation and antithrombotic prophylaxis in emergency department patientsStroke200233112664266912411658

- McCormickDGurwitzJHGoldbergRJPrevalence and quality of warfarin use for patients with atrial fibrillation in the long-term care settingArch Intern Med2001161202458246311700158

- SamsaGPMatcharDBGoldsteinLBQuality of anticoagulation management among patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a review of medical records from 2 communitiesArch Intern Med2000160796797310761962

- SorensenSVDewildeSSingerDEGoldhaberSZMonzBUPlumbJMCost-effectiveness of warfarin: trial versus “real-world” stroke prevention in atrial fibrillationAm Heart J200915761064107319464418

- SingerDEAlbersGWDalenJEGoASHalperinJLManningWJAntithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic TherapyChest2004126Suppl 3429S456S15383480

- AlbersGWDienerHCFrisonLXimelagatran vs warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a randomized trialJAMA2005293669069815701910

- BoulangerLKimJFriedmanMHauchOFosterTMenzinJPatterns of use of antithrombotic therapy and quality of anticoagulation among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in clinical practiceInt J Clin Pract200660325826416494639

- SullivanPWArantTWEllisSLUlrichHThe cost effectiveness of anticoagulation management services for patients with atrial fibrillation and at high risk of stroke in the USPharmacoeconomics200624101021103317002484

- GhateSRBiskupiakJYeXKwongWJBrixnerDIAll-cause and bleeding-related health care costs in warfarin-treated patients with atrial fibrillationJ Manag Care Pharm201117967268422050392

- BaetzBESpinlerSADabigatran etexilate: an oral direct thrombin inhibitor for prophylaxis and treatment of thromboembolic diseasesPharmacotherapy200828111354137318956996

- FranchiniMMannucciPMA new era for anticoagulantsEur J Intern Med200920656256819782914

- De CaterinaRKristensenSDRendaGNew anticoagulants for atrial fibrillationJ Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown)200910644645319365276

- SamamaMMGerotziafasGTNewer anticoagulants in 2009J Thromb Thrombolysis20102919210419838770

- PatelMRMahaffeyKWGargJRivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20113651088389121830957

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA approves Xarelto to prevent stroke in people with common type of abnormal heart rhythm [press release]November 42011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm278646.htmAccessed November 7, 2011

- ConnollySJEikelboomJJoynerCApixaban in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2011364980681721309657

- GrangerCBAlexanderJHMcMurrayJJApixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med20113651198199221870978

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA approves Pradaxa to prevent stroke in people with atrial fibrillationOctober 192010 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm230241.htmAccessed July 13, 2011

- EzekowitzMDConnollySParekhARationale and design of RE-LY: randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy, warfarin, compared with dabigatranAm Heart J2009157580581019376304

- ConnollySJEzekowitzMDYusufSDabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2009361121139115119717844

- WannLSCurtisABJanuaryCT2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (updating the 2006 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelinesCirculation201112310412321173346

- ReynoldsMREssebagVZimetbaumPCohenDJHealthcare resource utilization and costs associated with recurrent episodes of atrial fibrillation: the FRACTAL registryJ Cardiovasc Electrophysiol200718662863317451468

- GronefeldGCLilienthalJKuckKHHohnloserSHImpact of rate versus rhythm control on quality of life in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from a prospective randomized studyEur Heart J200324151430143612909072

- CarlssonJMiketicSWindelerJRandomized trial of rate-control versus rhythm-control in persistent atrial fibrillation: the Strategies of Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (STAF) studyJ Am Coll Cardiol200341101690169612767648

- van GelderIHagensVEBoskerHAA comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2002347231834184012466507

- RoyDTalajicMNattelSRhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failureN Engl J Med2008358252667267718565859

- MarshallDALevyARVidailletHCost-effectiveness of rhythm versus rate control in atrial fibrillationAnn Intern Med2004141965366115520421

- CorleySDEpsteinAEDiMarcoJPRelationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) StudyCirculation2004109121509151315007003

- FreemanJVZhuRPOwensDKCost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillationAnn Intern Med2011154111121041570

- ShahSVGageBFCost-effectiveness of dabigatran for stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillationCirculation2011123222562257021606397

- KamelHJohnstonSCEastonJDKimASCost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and prior stroke or transient ischemic attackStroke201243388188322308255

- PinkJLaneSPirmohamedMHughesDADabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analysesBMJ2011343d633322042753

- HohnloserSHCrijnsHJvan EickelsMEffect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2009360766867819213680

- NaccarelliGVJohnstonSSLinJPatelPPSchulmanKLCost burden of cardiovascular hospitalization and mortality in ATHENA-like patients with atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter in the United StatesClin Cardiol201033527027920513065

- EhrlichJRNattelSAtrial-selective pharmacological therapy for atrial fibrillation: hype or hope?Curr Opin Cardiol2009241505519077816

- BajpaiASavelievaICammAJTreatment of atrial fibrillationBr Med Bull2008881759419059992

- sanofi-aventisMultaq [package insert]Bridgewater, NJsanofi-aventis US LLC2012

- ConnollySJCrijnsHJTorp-PedersenCAnalysis of stroke in ATHENA: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm trial to assess the efficacy of dronedarone 400 mg BID for the prevention of cardiovascular hospitalization or death from any cause in patients with atrial fibrillation/atrial flutterCirculation20091201174118019752319

- DavyJMHeroldMHoglundCDronedarone for the control of ventricular rate in permanent atrial fibrillation: the Efficacy and safety of dRonedArone for The cOntrol of ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation (ERATO) studyAm Heart J2008156352752918760136

- SinghBNConnollySJCrijnsHJDronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutterN Engl J Med20073571098799917804843

- TouboulPBrugadaJCapucciACrijnsHJEdvardssonNHohnloserSHDronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a dose-ranging studyEur Heart J200324161481148712919771

- KoberLTorp-PedersenCMcMurrayJJIncreased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failureN Engl J Med2008358252678268718565860

- ConnollySJCammAJHalperinJLDronedarone in high-risk permanent atrial fibrillationN Engl J Med2011365242268227622082198

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA Drug Safety Communication: Severe liver injury associated with the use of dronedarone (marketed as Multaq)January 142011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm240011.htmAccessed July 13, 2011

- US Food and Drug AdministrationPotential signals of serious risks/new safety information identified by the adverse event reporting system (AERS) between July–September 2010January 112011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm237585.htmAccessed March 21, 2011

- QuarterWatchQuarterWatch: 2010 Quarter 1. Monitoring MedWatch ReportsSignals for acetaminophen, dronedarone and botulinum toxin products [executive summary]November 42010 Available from: http://freepdfhosting.com/078147c86d.pdfAccessed March 21, 2011

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA Drug Safety Communication: review update of multaq (dronedarone) and increased risk of death and serious cardiovascular adverse eventsDecember 212011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm283933.htmAccessed January 3, 2012

- MerckMerck to Acquire Rights to Vernakalant i.v. in Canada, Mexico and the United States from AstellasJul 262011 Available from: http://www.merck.com/newsroom/news-release-archive/research-and-development/2011_0726.htmlAccessed November 1, 2011

- CammAJCapucciAHohnloserSHA randomized active-controlled study comparing the efficacy and safety of vernakalant to amiodarone in recent-onset atrial fibrillationJ Am Coll Cardiol201157331332121232669

- ChengJWVernakalant in the management of atrial fibrillationAnn Pharmacother200842453354218334607

- EhrlichJRNattelSNovel approaches for pharmacological management of atrial fibrillationDrugs200969775777419441867

- NaultIMiyazakiSForclazADrugs vs ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: the evidence supporting catheter ablationEur Heart J20103191046105420332181

- CappatoRCalkinsHChenSAWorldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillationCirculation200511191100110515723973

- ChanPSVijanSMoradyFOralHCost-effectiveness of radio frequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillationJ Am Coll Cardiol200647122513252016781382

- ReynoldsMRZimetbaumPJosephsonMEEllisEDanilovTCohenDJCost-effectiveness of radiofrequency catheter ablation compared with antiarrhythmic drug therapy for paroxysmal atrial fibrillationCirc Arrhythm Electrophysiol20092436236919808491

- RodgersMMcKennaCPalmerSCurative catheter ablation in atrial fibrillation and typical atrial flutter: systematic review and economic evaluationHealth Technol Assess20081234iiixiii1