Abstract

Background

As part of the efforts to curb obesity, a new focus seems to be put on taxing foods that are perceived as being associated with obesity (eg, sugar-sweetened beverages and foods high in fat, sugar, and salt content) as a policy instrument to promote healthier diets.

Objective

To assess the possible effects of such taxation policies by identifying and analyzing all studies which investigate the impact of price increases on consumption, caloric intake, or weight outcomes.

Methods

Electronic data bases were searched with appropriate terms and their combinations. Thereafter, abstracts were reviewed and studies were selected based on predefined criteria. The characteristics of the selected studies and the results were extracted in a special form and consequently were reviewed and synthesized.

Results

Price increase may lead to a reduction in consumption of the targeted products, but the subsequent effect on caloric intake may be much smaller. Only a limited number of the identified studies reported weight outcomes, most of which are either insignificant or very small in magnitude to make any improvement in public health.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of a taxation policy to curb obesity is doubtful and available evidence in most studies is not very straightforward due to the multiple complexities in consumer behavior and the underling substitution effects. There is need to investigate in-depth the potential underlying mechanisms and the relationship between price-increase policies, obesity, and public health outcomes.

Introduction

Obesity prevalence is increasing worldwide, affecting both developed and developing countries. The prevalence of overweight and obese adults was estimated at 1.5 billion globally in 2008 by the World Health Organization, and this figure is projected to reach 2.3 billion by 2015.Citation1 There is accumulated scientific evidence indicating that obesity is strongly related to a vast number of diseases, including hypertension, hypercholes-terolemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, respiratory conditions, arthritis, and certain types of cancer. Moreover, obesity reduces the quality of life of individuals.Citation2

Along with morbidity and mortality, obesity also imposes a great economic burden upon society, which stems from the resources expended in the health care system to manage it, the expenditures incurred by sufferers and their families to cope with its consequences, and also the lost production caused by informal care, premature death, and inability to work.Citation2 Several studies in European countries estimate the health care-related costs of obesity at 1.7%–3.0% of total health expenditure,Citation3 while in the USA, it has been estimated that obesity accounts for almost 5%–10% of the total health care expenditure.Citation4 At the individual level, studies indicate that an obese person incurs health care expenditures at least 25% higher than those of a normal-weight person.Citation5,Citation6 On the other hand, indirect cost, ie, increased production as a result of a health condition, is also significant. Notably, employers in some countries often pay higher insurance premiums for employees who are obese in comparison to employees who are not.Citation7 In this context, some studies have also shown that obesity is associated with lower wages and lower household income.Citation8,Citation9 In this light, obesity constitutes a growing public health problem and concern throughout the world. Therefore, strategies aiming to prevent obesity are of paramount importance for both health and economic reasons.

Several factors have been linked to obesity, including socioeconomic, environmental, behavioral, and genetic. Total energy intake increase in conjunction with physical activity decrease has been indicated as a contributor to the obesity trend.Citation10 In this context, it has been argued that overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and high-in-fat, salt, and sugar foods (HFSSFs) may be associated with excess caloric intake and eventually increases in body weight.Citation11,Citation12 Thus, some authors suggest that mediating consumption of SSBs and HFSSFs in populations that exhibit relatively excess consumption rates could prove an effective intervention in reducing subsequently obesity rates.Citation10 In this context, taxes on HFSSFs and SSBs, often called “fat or sugar taxes,” have been introduced or are being considered in several countries as a means to regulate the consumption of these products and eventually to curb obesity, to trim health care costs, to raise revenue, and ultimately improve public health.Citation13 On the other hand, a number of countries have abandoned the policy route of taxing foods either by abolishing existing taxes, eg, Denmark and the Netherlands, or by shelving respective ideas, eg, Italy.Citation14

In any case, such taxes have provoked considerable controversy among the various stakeholders: the government, academic, scientific, health, and medical communities, consumers and their associations, and the food industry. Based on economic theory, the main rationale underpinning the adoption of such policies is that a tax and price increase on the targeted products may avert consumers from their consumption and divert them to healthier alternatives, and in this way there may be improvements in diet quality, weight status, and health outcomes in the long-term. Supporters of the fat taxation often also emphasize its signaling power to the food industry and consumers and its efficiency in raising revenue.Citation15

On the other hand, opponents of such taxes argue that there are many factors which make such policies ineffective and even detrimental in certain circumstances.Citation16 Firstly, interventions of these kinds of taxes/policies represent a violation of consumer sovereignty, ie, the freedom of individuals to choose freely for themselves in order to satisfy their needs. Regardless, it is difficult to attain the desired results because consumer behavior is complex and multifactorial and there are notable substitution effects which make the reduction in total energy intake by specific taxes unattainable. Taxes are also regressive in nature and the burden is proportionally higher on lower-income households, which generates significant equity concerns. Also, the approach presumes well-informed and price-sensitive consumers, which is not always the case, and hence there is a market failure that makes the specific policy ineffective. Therefore, many commentators argue that the aim of improving public health is unquestionably important, but taxes may not be the most appropriate policy measure to attain it.Citation13

Hence, given the controversy around this issue, a systematic review was undertaken to synthesize the results of original studies examining the possible impact of tax policies and price increases upon the consumption of SSBs and HFSSFs and eventually upon caloric intake, weight, and outcomes in order to provide useful insights for decision makers and other stakeholders nationally and internationally.

Methods

Search strategy

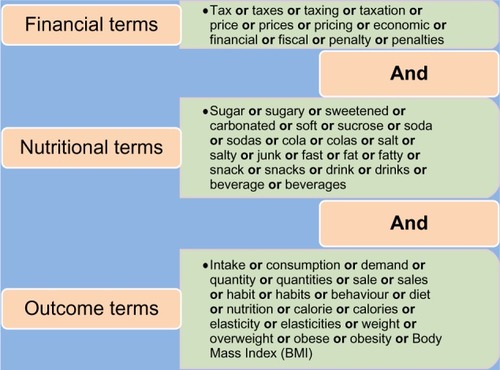

Research papers were identified through web-based searches in PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, AgEcon, EconLit, and the National Agricultural Library databases and searches in other potentially relevant internet sources such as Google®. Searching in the aforementioned bibliographical databases was conducted in the title and abstract on grounds of all potential combinations of three groups of terms presented in . The reference lists of all relevant papers originally selected for inclusion in the review and relevant reviews were also searched manually to identify potentially relevant articles which were not identified by the original electronic search. The search spanned from 1990 to February 2013. The stated aim of this fiscal measure was not only to offset this price imbalance but also – as is often the case with excise taxation – to raise revenue, in particular to collect resources to be invested in nutrition programs.Citation17,Citation18

Study selection and data extraction

Following the literature search, identified studies were checked to exclude duplicates. The remaining articles were independently screened by two researchers to identify studies that met the predetermined inclusion criteria. Original studies including the four types of primary research methods – existing data, experiments, surveys, and observation – that focused on the association between SSBs and HFSSFs prices and taxes and their corresponding consumption or energy intake or obesity-related outcomes were included in the present systematic review. On the other hand, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, qualitative studies, case studies, case reports, and letters to the editor were excluded. Moreover, only studies published in English with available full text and studies concerning human subjects were included.

The studies were selected following specific methodologically driven steps. Firstly, all identified studies were imported electronically into EndNote® bibliographic database (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) and were evaluated on the basis of titles and/or abstracts against the prespecified eligibility criteria. A check for double entries among the selected studies was made to ensure that the list contained unique studies for review. Subsequently, study abstracts and titles were reviewed and those which were deemed irrelevant were excluded and reasons for exclusion were noted. Obviously, rejected studies were those clearly not relevant to the subject of investigation. Whenever the information provided in titles/abstracts was insufficient to reach a clear decision on inclusion or exclusion or when the titles/abstracts indicated that studies met the inclusion criteria, the full papers were retrieved to be further screened. In cases where the information reported in the full text continued to be insufficient to make a decision about inclusion, studies were excluded. Then, essential details and data of studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted by two researchers into a spreadsheet and were classified according to their design – demand modeling, cross-sectional, longitudinal, mathematical modeling, cohort retrospective, and experimental. The overall study selection process was also documented through a flow chart showing the number of studies/papers remaining at each stage, although a screening process to identify articles using the studies bibliography had been done. The review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria.

Results

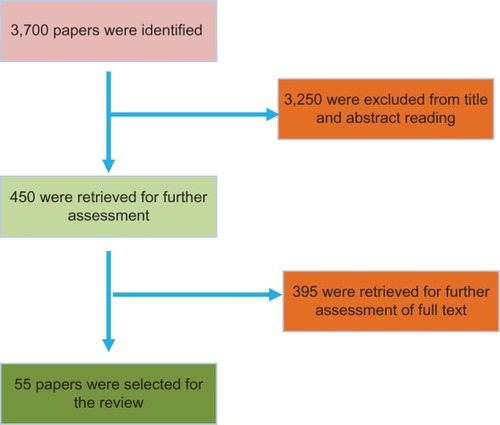

The initial literature review identified 3,700 citations for screening. Of these, 3,250 were excluded on the basis of title/abstract and 395 after screening the full paper. Subsequently, a total of 55 were finally included in the review ().

In terms of geographical location, most of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 40) and the remaining in the UK (n = 2), Norway, Italy (n = 2), Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Mexico (n = 2), Brazil, Taiwan, Singapore, and Australia. In terms of methodologies utilized, there was significant variation in terms of the research designs applied. In particular, there were several demand studies (n = 22), followed by longitudinal studies (n = 11), cross-sectional studies (n = 11), modeling studies (n = 6), experimental studies (n = 4), and cohort studies (n = 1). The majority of the studies were mainly focused on estimating price elasticity of demand (n = 30), others mainly focused on the effects of imposing certain taxation (n = 18), and the remaining studies considered both elements (n = 8). Health-related food taxes were either considered as excise or sales taxes. In terms of the targeted products, about half (n = 28) of the studies focused on SSBs only and the remaining (n = 36) either on HFSSFs alone or on HFSSFs in conjunction with SSBs.

In terms of the main outcomes considered, about half of the studies (n = 24) were concerned mainly with the effects of various interventions upon the consumption of products and the remaining (n = 31) upon other outcomes such as energy intake and/or weight and/or body mass index (BMI). Notably, some studies reported results for all three outcomes of interest: energy intake, weight, and BMI.

The studies considered are presented in the Supplementary material. In particular, among the demand studies, nine presented the association between prices and taxes with the consumption of SSBsCitation19–Citation27 and three with the consumption of HFSSFs.Citation28–Citation30 These studies indicated that the price elasticity of demand for beverages is in the range of −0.5 to −1.6 depending on the beverage considered, with most of them falling below 1.0. This implies that the percentage changes in the quantities demanded were proportionally lower than the corresponding changes in prices. It should be noted that there was a lot of variation across the studies. There were also notable substitution effects detected between different products. The studies also pointed out that the negative effects on the consumption by price increases and taxes depend on factors such as the income group, and are more regressive towards the lowest income categories. Similar effects were found in the studies that focused on foods, also indicating a small or modest impact from price increase and taxes on the consumption of the targeted foods.

Moreover, six studiesCitation28,Citation29,Citation31–Citation34 and five studiesCitation35–Citation39 examined the association between beverage/food prices and taxes and energy and weight outcomes, respectively. These studies indicated that there is a very small impact of prices and taxes on energy intake and weight outcomes. These studies indicated that the caloric effect of a 10% increase in prices or a corresponding imposition of a tax reduces energy intake by a maximum of 50 calories per day, 450 per month, and up to 0.3 kilograms or 1.5 pounds per year, which cannot be considered significant. The specific studies also indicated the regressive nature of taxes and that their use is promoted mostly in order to generate revenue for the public purse.

Two studies assessed the effect of prices and taxes on the consumption of beverages and foods based on longitudinal studies.Citation40,Citation41 These studies indicated that the price elasticity of demand for beverages and foods is in the range of −0.05 to −0.35 depending on the beverage and food considered. Notably, the figures reported are much lower than those reported in demand studies. The findings in this group of studies also indicated that there are negative effects on consumption in most cases, which are more significant in certain groups, eg, overweight.

All studies investigated the effect of beverages/food prices or taxes with possible outcomes. For two studies,Citation42,Citation43 the outcome was energy intake, while for 16 studies,Citation35–Citation50 weight outcomes were considered. Elasticities were low and in some cases not significant, and results were heterogeneous and dependent on income, weight, sex, and age group. Notwithstanding the above, these studies indicated that there is a modest and insignificant impact from price increases and taxes on energy intake, weight, and BMI, which makes the authors argue that any taxes would have to be quite large to generate any meaningful effect. These studies also highlighted the regressive nature of taxes and that their usefulness is to mostly generate revenue.

Barquera et alCitation51 and Claro et alCitation52 examined the effect of prices on beverages consumption; Sturm and DatarCitation53 examined the effect on food consumption only. However, elasticities on this occasion for beverages and foods were a bit contradictory. A Mexican and a Brazilian study derived elasticities for sodas to be about –1.0, indicating that soda consumption is elastic whilst other beverages are in the inelastic range. By contrast, a USA study indicated that the elasticity of fast foods and soda in students is inelastic and effects of prices are inconsistent and marginal.

Moreover, six cross-sectional studiesCitation54–Citation59 examined the association between prices and energy outcomes, while two other studiesCitation60,Citation61 examined the association between prices and weight outcomes. The majority of the studies concluded that taxes are having trivial or modest effects on weight outcomes. These studies also indicated the regressive nature of taxes and that their use is mostly to generate revenue.

Some of the studies included in the review conducted behavioral experiments in the Netherlands, Taiwan, Singapore, and the USA. Particularly, four studiesCitation62–Citation65 reported results on the effects of prices and taxes on the consumption and other outcomes of beverages and foods, respectively. Elasticities on this occasion between beverages and food were close to −1.0, ie, the association is in the elastic range. The effect on caloric intake and weight outcomes was higher in other studies, assumedly due to much higher taxes in the range of 35%–50%.

Finally, six of the 55 studies reviewed were modeling studies undertaken in the USA (n = 3), UK (n = 2), and Australia (n = 1). Two of them used cross-sectional data and the others were based on census data.

Discussion

The current study presents the results of a literature review undertaken to establish whether the available evidence supports use of fat taxes as a means to improve weight and health outcomes. The existing literature fails to draw consistent and undisputed evidence on the effectiveness of pricing and tax policies to reduce obesity rates. The heterogeneity observed in the findings of the included studies could be partially explained by the significant heterogeneity in policy settings and study designs employed to investigate the issue. It is evident that price and tax increases on beverages and fatty foods may reduce their consumption. However, there is controversy as to whether this also may result in meaningful reductions in caloric intake and weight. The studies that show some positive impact of economic policies also indicate that any potential reductions in weight are statistically insignificant to trigger desired effects. Moreover, elasticities indicate that significant weight outcome effects may be reached with very large tax rates, which would, however, exacerbate equity concerns related to their adverse implications for low-income groups.

At this point it should be noted that there are several important factors – obesity prevalence, consumption levels, behavioral patterns, and baseline tax rate – that should be considered within local contexts when contemplating the potential benefits of taxation.Citation66 When any of these factors shift, the potential impact of fat taxation becomes less certain and unpredictable. However, it is very difficult to estimate how a population would respond to a tax on certain foods.Citation67 Some consumers may respond by reducing their consumption of fruits and vegetables in order to pay for the more expensive HFSSFs, thus defeating the purpose of the tax. Others may seek substitutes for the taxed products, which may have similar or even higher fat, sugar, or salt content than the taxed products originally consumed. Thus, although there may be a decrease in the purchasing of the taxed food, consumers may end up consuming the same or even more calories from other substitute foods or drinks. This is in accordance with the findings of many studies in the literature.Citation57,Citation68–Citation72

Moreover, to effectively apply policies to reduce consumption of high-calorie, high-fat, or high-carbohydrates foods, policy analysts need to disaggregate food-specific demand estimates according to socioeconomic status and assess the possible impacts of policy changes on food consumption and welfare outcomes at a more disaggregated level in addition to the total effects. This could be explained by the fact that the expenditure shared for food and consumption behaviors may differ significantly among different socioeconomic groups.Citation73 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2010 reported that the impact of fiscal measures aiming to change behaviors may be unpredictable; because the price elasticity of demand varies across individuals and population groups, these measures can bear more heavily on low-income groups than on those with higher incomes, and substitution effects are not always obvious.Citation74 Further to considering the above, one needs to consider which products will be the targets of intervention.

Moreover, in regard to SSBs, the association between their consumption and overweight is a complex metabolic relationship and there are many behavioral and environmental factors that may be influencing beverage and food consumption and weight. Many of the food tax policies implemented are focusing on soft drinks as a number of influential reports assert that sugary drinks play a key role in the etiology of obesity. Contrary to this premise, a 2012 report from the National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined data on consumption of added sugars among US children and adolescents and reported that added sugar from food (59%) was higher than sugar from beverages (41%).Citation75 Moreover, research published in 2010 from Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, UK, shows that SSBs consumed in moderate quantities do not promote short-term weight gain, do not trigger additional carbohydrate intake, and do not generate changes in the moods of overweight women.Citation76 In 2007, there was a similar study performed on average-weight women and came out with similar conclusions.Citation77 Hence, evidence suggests that the hypothetic contribution of SSBs on weight gain perhaps has been overestimated.Citation78–Citation80

Moreover, broader taxes on HFSSFs would possibly allow less substitution than narrow taxes.Citation81 However, a concern with taxing a wide range of products would be the fact that people should be encouraged to consume a wide range of food and beverage products, eg, milk and olive oil, that would be difficult to include in the tax category.Citation81 Furthermore, in some cases, taxing many food groups could possibly lead to nutrient deficiencies, in which case economic policies may have harmful nutritional and health effects.Citation38,Citation82

Based on the above, there is no doubt that a public health approach to develop population-based strategies for the prevention of excess weight gain is of great importance.Citation83,Citation84 Some effective strategies involve changes to personal, environmental, and socioeconomic factors associated with obesity. A proposed framework by Sacks et alCitation85 suggests that policy actions on the development and implementation of effective public health strategies on obesity prevention should (1) deal with the food environments, the physical activity environments, and the broader socioeconomic environments; (2) directly influence behavior, aiming at improving eating and physical activity behaviors; and (3) support health services and clinical interventions. There are abundant examples of the effectiveness of such measures.Citation85–Citation95 Lastly, a number of barriers to an effective obesity management program have been identified in the literature that policy makers need to be aware of in order to address them adequately.Citation96–Citation107 However, the development and implementation of obesity prevention strategies should target those factors that can effectively control obesity.

For instance, in Greece it is proven that obesity is a growing health problem and concern. However, there is accumulating evidence indicating that SSBs may not be a determinant of obesity in Greece. For instance, a 2006 study examined energy intake, energy expenditure, diet composition, and obesity of adolescents in northern Greece, and showed that cola drink consumption did not significantly differ between overweight and non-overweight adolescents.Citation108 Additionally, in another recent study in children aged 10–12 years old, it was found that although Spain and Greece had the highest obesity rates among the European countries examined, they also had the lowest soft drink daily consumption.Citation109 It is important to note, however, that Greek children had lower physical activity levels and were reported to skip breakfast more often than their counterparts in other countries.Citation109 Finally, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study showed that Greek adults over 35 years have the lowest consumption of sugar among the European countries that participated in the research program. Additionally, in the same study, it was also shown that nonalcoholic and carbonated drinks contribute a minor percentage of total carbohydrate daily intake – indicatively 2.8% of total carbohydrate intake in men and 1.8% of total carbohydrate intake in women – and an even lower percentage of total energy daily intake.Citation110 The above data suggest that soft drink consumption may be a minor contributor to energy and carbohydrate intake in Greece in children, adolescents, and adults. The high obesity phenomenon in Greece is probably due to excess fat consumption in combination with lack of exercise. Therefore, targeting SSBs for obesity management or prevention in Greece is not an effective approach to curtailing obesity epidemic trends. Proper policies and interventions need to be designed based on the grounds of this local evidence.

The results of this review must be interpreted cautiously. First of all, in many studies, transformation of consumption figures to energy and weight outcomes was often based on extrapolation models, which require careful consideration. Caution must be directed to the model that is used to translate energy intake changes to weight changes. Using static weight models may provide quite different estimates in comparison to dynamic weight models. Static models generate a linear reduction in body weight over time, based on the assumption that every pound in weight reduction accounts for almost 3,500 calories, which is an assumption that has been challenged in the literature, and if not true undermines many findings. On the other hand, dynamic models account for the effects of weight loss by assuming changes in energy requirements due to weight reduction and fat and lean mass proportion, but they also involve various assumptions.Citation35 Secondly, when weight outcomes in certain studies are obtained directly and not through modeling, it is important to consider whether the measurements were obtained with objective assessments or were based on self-reporting.

Thirdly, in regards to the estimation of caloric intake effects, it is important to consider whether any potential changes are referring to energy intake related to the targeted product taxed or to the total energy intake in general. Due to the substitution effects, the total outcome is far more interesting from a policy perspective. Additionally, when total energy intake is considered, it is essential to clarify how it was estimated and whether possible substitution was taken into account as there are strong substitution dynamics between different foods. For instance, a soft drink tax may lead to reduction in calories due to consumption of soft drinks, but this reduction may be completely offset by the increase in the consumption of milk.Citation56

Last but not least, in some studies, the populations investigated were not representative or adequately described and the studies have been undertaken in specific settings, which are difficult to extrapolate to European populations and policy environments in light of the fact that results are dependent on population behavioral aspects.

Conclusion

The systematic review of the literature demonstrated that the effect of price and tax increase upon the consumption of SSBs and HFSSFs and eventually upon caloric intake and obesity-related outcomes is controversial. To be more precise, there is strong evidence that such measures influence the consumption of SSBs and HFSSFs, but there is no significant effect on obesity-related outcomes, ie, weight, BMI, and obesity. Thus, more research is needed in this area to gain better insights on the use of economic policies aimed at addressing obesity trends, especially from a European perspective. Moreover, when considering environmental, socioeconomic, and genetic contributors to obesity, it is advisable that policies focus first on cognitive behavioral changes and then on environmental factors. Such policies would create conscious people who are aware of the obesity problem and the main cause of weight gain, which is energy imbalance, and also its possible solutions, including encumbrances due to genetic or habitual factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Medical Consensus.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Studies on price and tax interventions and their effects on different outcomes

References

- GustavsenGWPublic policies and the demand for carbonated soft drinks: a censored quantile regression approachPoster presented at: 11th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 23–27, 2005Copenhagen, Denmark

- YenSTLinBHSmallwoodDMAndrewsMDemand for nonalcoholic beverages: the case of low-income householdsAgribusiness2004203309321

- BrownMGLeeJYSealeJLDemand relationships among juice beverages: a differential demand system approachJournal of Agricul tural and Applied Economics1994262417429

- PofahlGMCappsOJrClausonADemand for non-alcoholic beverages: evidence from the ACNielsen Home Scan PanelPoster presented at: American Agricultural Economics Association Annual MeetingJuly 24–27, 2005Providence, RI

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrDemand interrelationships of at home nonalcoholic beverage consumpion in the United StatesPoster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association and American Council on Consumer Interests Joint Annual MeetingJuly 28, 2009Milwaukee, WI

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrOn taxing sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the obesity problemPoster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Canadian Agricultural Economics Society, and Western Agricultural Economics Association Joint Annual MeetingJuly 27, 2010Denver, CO

- BrownMGJaureguiCEConditional Demand System For BeveragesGainesville, FLFlorida Department of Citrus2011 Available from: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/104335/2/RP%202011-1.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- BrownGMImpact of income on price and income responses in the differential demand systemJournal of Agricultural and Applied Economics2008402593608

- ZhengYKaiserHMEstimating assymetric advertising response: an application to US nonalcoholic beverage demandJournal of Agricultural and Applied Economics2008403837849

- ZhenMBeghinJCJensenHHAccounting for Product Substitution in the Analysis of Food Taxes Targeting ObesityAmes, IACenter for Agricultural and Rural Development2011 Available from: http://www.card.iastate.edu/publications/dbs/pdffiles/10wp518.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- PieroniLLanariDSalmasiLFood prices and overweight patterns in ItalyEur J Health Econ201314113315121935716

- KuchlerFTegeneAHarrisJMTaxing snack foods: manipulating diet quality or financing information programs?Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy2005271420

- ChouinardHHDavisDELaFranceJTPerloffJMFat taxes: big money for small changeForum Health Econ Policy200710215589544

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrIntended and unintended consequences of a proposed national tax on sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the US obesity problemHealth Econ201221666969421538676

- GustavsenGWRickertsenKThe effects of taxes on purchases of sugar-sweetened carbonated soft drinks: a quantile regression approachAppl Econ2011436707716

- LinBHSmithTALeeJYHallKDMeasuring weight outcomes for obesity intervention strategies: the case of a sugar-sweetened beverage taxEcon Hum Biol20119432934121940223

- SmedSJensenJDDenverSDifferentiated food taxes as a tool in health and nutrition policyPoster presented at: 11th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 23–27, 2005Copenhagen, Denmark

- ThieleSFat tax: a political measurement to reduce overweight? The case of GermanyPoster presented at: 1st Joint European Association of Agricultural Economists and Agricultural and Applied Economics Association SeminarSeptember 15–17, 2010Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany

- MeyerhoeferCDLeibtagESA spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: the relationship between food prices and medical expenditures on diabetesAm J Agric Econ201092512711282

- ZhenMBeghinJCJensenHHAccounting for Product Substitution in the Analysis of Food Taxes Targeting ObesityAmes, IACenter for Agricultural and Rural Development2011 Available from: http://www.card.iastate.edu/publications/dbs/pdffiles/10wp518.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- AllaisOBertailPNicheleVThe effects of a “fat tax” on the nutri ent intake of French householdsPoster presented at: 12th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 26–29, 2008Ghent, Belgium

- Gordon-LarsenPGuilkeyDKPopkinBMAn economic analysis of community-level fast food prices and individual-level fast food intake: a longitudinal studyHealth Place20111761235124121852178

- KhanLKSobushKKeenerDRecommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United StatesMMWR Recomm Rep200958RR-712619629029

- SturmRPowellLMChriquiJFChaloupkaFJSoda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children’s body mass indexHealth Aff (Millwood)20102951052105820360173

- FinkelsteinEAZhenCNonnemakerJToddJEImpact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income householdsArch Intern Med2010170222028203421149762

- PowellLMFast food costs and adolescent body mass index: evidence from panel dataJ Health Econ200928596397019732982

- WendtMToddJEThe Effect of Food and Beverage Prices on Children’s WeightsWashington DCUS Department of Agriculture2011 Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/123670/err118.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- PowellLMChaloupkaFJFood prices and obesity: evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidiesMilbank Q200987122925719298422

- DuffeyKJGordon-LarsenPShikanyJMGuilkeyDJacobsDRJrPopkinBMFood price and diet and health outcomes: 20 years of the CARDIA StudyArch Intern Med2010170542042620212177

- WendtMToddJEDo low prices for sugar-sweetened beverages increase children’s weights?Poster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Canadian Agricultural Economics Society, and Western Agricultural Economics Association Joint Annual MeetingJuly 27, 2010Denver, CO

- AuldCMPowellLMEconomics of food energy density and adolescent body weightEconomica200976304719740

- ZhangQChenZDiawaraNWangYPrices of unhealthy foods, food stamp program participation, and body weight status among US low-income womenJ Fam Econ Issues2011322245256

- HanEPowellLMEffect of food prices on the prevalence of obesity among young adultsPublic Health2011125312913521272902

- BarqueraSHernandez-BarreraLTolentinoMLEnergy intake from beverages is increasing among Mexican adolescents and adultsJ Nutr2008138122454246119022972

- ClaroRMLevyRBPopkinBMMonteiroCASugar-sweetened beverage taxes in BrazilAm J Public Health2012102117818322095333

- SturmRDatarARegional price differences and food consumption frequency among elementary school childrenPublic Health2011125313614121315395

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDTefftNCan soft drink taxes reduce population weight?Contemp Econ Policy2010281233520657817

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDETefftNThe effects of soft drink taxes on child and adolescent consumption and weight outcomesJ Public Econ20109411–12967974

- PowellLMZhaoZWangYFood prices and fruit and vegetable consumption among young American adultsHealth Place20091541064107019523869

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDTefftNTaxing soft drinks and restricting access to vending machines to curb child obesityHealth Aff (Millwood)20102951059106620360172

- WangYCCoxsonPShenYMGoldmanLBibbins-DomingoKA penny-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would cut health and cost burdens of diabetesHealth Aff (Millwood)201231119920722232111

- BeydounMAPowellLMChenXWangYFood prices are associated with dietary quality, fast food consumption, and body mass index among US children and adolescentsJ Nutr2011141230431121178080

- ArroyoPLoriaAMendezOChanges in the household calorie supply during the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico and its implications on the obesity epidemicNutr Rev2004627 Pt 2S163S16815387484

- BeydounMAPowellLMWangYThe association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: is there modification by family income?Soc Sci Med200866112218222918313824

- BlockJPChandraAMcManusKDWilletWCPoint-of-purchase price and education intervention to reduce consumption of sugary soft drinksAm J Public Health201010081427143320558801

- YangCCChiouWBSubstitution of healthy for unhealthy beverages among college students. A health-concerns and behavioral-economics perspectiveAppetite201054351251620156500

- NederkoornCHavermansRCGiesenJCJansenAHigh tax on high energy dense foods and its effects on the purchase of calories in a supermarket. An experimentAppetite201156376076521419183

- EpsteinLHDearingKKRobaLGFinkelsteinEThe influence of taxes and subsidies on energy purchased in an experimental purchasing studyPsychol Sci201021340641420424078

- AndreyevaTChaloupkaFJBrownellKDEstimating the potential of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce consumption and generate revenuePrev Med201152641341621443899

- MyttonOGrayARaynerMRutterHCould targeted food taxes improve health?J Epidemiol Community Health200761868969417630367

- SchroeterCLuskJTynerWDetermining the impact of food price and income changes on body weightJ Health Econ2008271456817521754

- NnoahamKESacksGRaynerMMyttonOGrayAModelling income group differences in the health and economic impacts of targeted food taxes and subsidiesInt J Epidemiol20093851324133319483200

- FinkelsteinEAZhenCBilgerMNonnemakerJFarooquiAMToddJEImplications of a sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) tax when substitutions to non-beverage items are consideredJ Health Econ201332121923923202266

- SacksGVeermanJLMoodieMSwinburnB“Traffic-light” nutrition labelling and “junk-food” tax: a modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity preventionInt J Obes (Lond)20113571001100921079620

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Obesity and overweight: fact sheet no 311 [webpage on the Internet]GenevaWorld Health Organization2012 [cited Nov 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.htmlAccessed August 13, 2013

- SassiFObesity and the Economics of Prevention: Fit Not FatParisOECD Publishing2010 Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/46044572.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- BrancaFNikogosianHLobsteinTThe Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies For ResponseGenevaWorld Health Organization2007 Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/98243/E89858.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- TsaiAGWilliamsonDFGlickHADirect medical cost of overweight and obesity in the USA: a quantitative systematic reviewObes Rev2011121506120059703

- WithrowDAlterDAThe economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesityObes Rev201112213114120122135

- CawleyJMeyerhoeferCThe medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approachJ Health Econ201231121923022094013

- TrogdonJGFinkelsteinEAHylandsTDelleaPSKamal-BahlSJIndirect costs of obesity: a review of the current literatureObes Rev20089548950018331420

- LehnertTSonntagDKonnopkaAReidel-HellerSKonigHEconomic costs of overweight and obesityBest Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab201327210511523731873

- HojgaardBOlsenKRSogaardJSorensonTIGyrd-HansenDEconomic costs of abdominal obesityObes Facts20081314615420054174

- MalikVSWillettWCHuFBGlobal obesity: trends, risk factors, and policy implicationsNat Rev Endocrinol201391132723165161

- VartanianLRSchwartzMBBrownellKDEffects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Public Health200797466767517329656

- MalikVSSchulzeMBHuFBIntake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic reviewAm J Clin Nutr200684227428816895873

- MyttonOTClarkeDRaynerMTaxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve healthBMJ2012344e293122589522

- BomsdorfCDenmark scraps much-aligned “fat tax” after a yearThe Wall Street Journal11112012Sect A12

- LeighS“Twinkie tax” worth a try in fight against obesityU S A Today1222004Sect A13

- CashSBSundingDLZilbermanDFat taxes and thin subsidies: prices, diet, and health outcomesActa Agriculturae Scandinavica Section C – Food Economics20052167174

- BrownellKDFarleyTWillettWCThe public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beveragesN Engl J Med2009361161599160519759377

- LeicesterAWindmeijerFThe “Fat Tax”: Economic Incentives To Reduce Obesity (Briefing Note 49)LondonThe Institute for Fiscal Studies2004 Available from: http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/14931/1/14931.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- BrownGMImpact of income on price and income responses in the differential demand systemJournal of Agricultural and Applied Economics2008402593608

- BrownMGJaureguiCEConditional Demand System For BeveragesGainesville, FLFlorida Department of Citrus2011 Available from: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/104335/2/RP%202011-1.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- Brown MarkGLeeJYSealeJLDemand relationships among juice beverages: a differential demand system approachJournal of Agricultural and Applied Economics1994262417429

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrDemand interrelationships of at home nonalcoholic beverage consumpion in the United StatesPoster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association and American Council on Consumer Interests Joint Annual MeetingJuly 28, 2009Milwaukee, WI

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrOn taxing sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the obesity problemPoster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Canadian Agricultural Economics Society, and Western Agricultural Economics Association Joint Annual MeetingJuly 27, 2010Denver, CO

- GustavsenGWPublic policies and the demand for carbonated soft drinks: a censored quantile regression approachPoster presented at: 11th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 23–27, 2005Copenhagen, Denmark

- PofahlGMCappsOJrClausonADemand for non-alcoholic beverages: evidence from the ACNielsen Home Scan PanelPoster presented at: American Agricultural Economics Association Annual MeetingJuly 24–27, 2005Providence, RI

- YenSTLinBHSmallwoodDMAndrewsMDemand for nonalcoholic beverages: the case of low-income householdsAgribusiness2004203309321

- ZhengYKaiserHMEstimating assymetric advertising response: an application to US nonalcoholic beverage demandJournal of Agricultural and Applied Economics2008403837849

- KuchlerFTegeneAHarrisJMTaxing snack foods: manipulating diet quality or financing information programs?Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy2005271420

- PieroniLLanariDSalmasiLFood prices and overweight patterns in ItalyEur J Health Econ201314113315121935716

- ZhenCWohlgenantMKKarnsSKaufmanPHabit formation and demand for sugar-sweetened beveragesAm J Agric Econ2010931175193

- ChouinardHHDavisDELaFranceJTPerloffJMFat taxes: big money for small changeForum Health Econ Policy200710215589544

- DharmasenaSCappsOJrIntended and unintended consequences of a proposed national tax on sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the US obesity problemHealth Econ201221666969421538676

- GustavsenGWRickertsenKThe effects of taxes on purchases of sugar-sweetened carbonated soft drinks: a quantile regression approachAppl Econ2011436707716

- SenarathDDavisGCCappsOJrPartial versus general equilibrium calorie and revenue effects of a sugar-sweetened beverage taxPoster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association and Northeastern Agricultural and Resource Economics Association Joint Annual MeetingJuly 26, 2011Pittsburgh, PA

- LinBHSmithTALeeJYHallKDMeasuring weight outcomes for obesity intervention strategies: the case of a sugar-sweetened beverage taxEcon Hum Biol20119432934121940223

- MeyerhoeferCDLeibtagESA spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: the relationship between food prices and medical expenditures on diabetesAm J Agric Econ201092512711282

- SmedSJensenJDDenverSDifferentiated food taxes as a tool in health and nutrition policyPoster presented at: 11th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 23–27, 2005Copenhagen, Denmark

- ThieleSFat tax: a political measurement to reduce overweight? The case of GermanyPoster presented at: 1st Joint European Association of Agricultural Economists and Agricultural and Applied Economics Association SeminarSeptember 15–17, 2010Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany

- ZhenMBeghinJCJensenHHAccounting for Product Substitution in the Analysis of Food Taxes Targeting ObesityAmes, IACenter for Agricultural and Rural Development2011 Available from: http://www.card.iastate.edu/publications/dbs/pdffiles/10wp518.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- AllaisOBertailPNicheleVThe effects of a “fat tax” on the nutrient intake of French householdsPoster presented at: 12th Congress of the European Association of Agricultural EconomistsAugust 26–29, 2008Ghent, Belgium

- Gordon-LarsenPGuilkeyDKPopkinBMAn economic analysis of community-level fast food prices and individual-level fast food intake: a longitudinal studyHealth Place20111761235124121852178

- KhanLKSobushKKeenerDRecommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United StatesMMWR Recomm Rep200958RR-712619629029

- SturmRPowellLMChriquiJFChaloupkaFJSoda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children’s body mass indexHealth Aff (Millwood)20102951052105820360173

- AuldCMPowellLMEconomics of food energy density and adolescent body weightEconomica200976304719740

- DuffeyKJGordon-LarsenPShikanyJMGuilkeyDJacobsDRJrPopkinBMFood price and diet and health outcomes: 20 years of the CARDIA StudyArch Intern Med2010170542042620212177

- FinkelsteinEAZhenCNonnemakerJToddJEImpact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income householdsArch Intern Med2010170222028203421149762

- PowellLMFast food costs and adolescent body mass index: evidence from panel dataJ Health Econ200928596397019732982

- PowellLMChaloupkaFJFood prices and obesity: evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidiesMilbank Q200987122925719298422

- WendtMToddJEThe Effect of Food and Beverage Prices on Children’s WeightsWashington DCUS Department of Agriculture2011 Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/123670/err118.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- WendtMToddJEDo low prices for sugar-sweetened beverages increase children’s weights?Poster presented at: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Canadian Agricultural Economics Society, and Western Agricultural Economics Association Joint Annual MeetingJuly 27, 2010Denver, CO

- BarqueraSHernandez-BarreraLTolentinoMLEnergy intake from beverages is increasing among Mexican adolescents and adultsJ Nutr2008138122454246119022972

- ClaroRMLevyRBPopkinBMMonteiroCASugar-sweetened beverage taxes in BrazilAm J Public Health2012102117818322095333

- SturmRDatarARegional price differences and food consumption frequency among elementary school childrenPublic Health2011125313614121315395

- BeydounMAPowellLMChenXWangYFood prices are associated with dietary quality, fast food consumption, and body mass index among US children and adolescentsJ Nutr2011141230431121178080

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDTefftNTaxing soft drinks and restricting access to vending machines to curb child obesityHealth Aff (Millwood)20102951059106620360172

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDTefftNCan soft drink taxes reduce population weight?Contemp Econ Policy2010281233520657817

- FletcherJMFrisvoldDETefftNThe effects of soft drink taxes on child and adolescent consumption and weight outcomesJ Public Econ20109411–12967974

- PowellLMZhaoZWangYFood prices and fruit and vegetable consumption among young American adultsHealth Place20091541064107019523869

- WangYCCoxsonPShenYMGoldmanLBibbins-DomingoKA penny-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would cut health and cost burdens of diabetesHealth Aff (Millwood)201231119920722232111

- ArroyoPLoriaAMendezOChanges in the household calorie supply during the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico and its implications on the obesity epidemicNutr Rev2004627 Pt 2S163S16815387484

- BeydounMAPowellLMWangYThe association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: is there modification by family income?Soc Sci Med200866112218222918313824

- BlockJPChandraAMcManusKDWilletWCPoint-of-purchase price and education intervention to reduce consumption of sugary soft drinksAm J Public Health201010081427143320558801

- EpsteinLHDearingKKRobaLGFinkelsteinEThe influence of taxes and subsidies on energy purchased in an experimental purchasing studyPsychol Sci201021340641420424078

- NederkoornCHavermansRCGiesenJCJansenAHigh tax on high energy dense foods and its effects on the purchase of calories in a supermarket. An experimentAppetite201156376076521419183

- YangCCChiouWBSubstitution of healthy for unhealthy beverages among college students. A health-concerns and behavioral-economics perspectiveAppetite201054351251620156500

- JouJTechakehakijWInternational application of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxation in obesity reduction: factors that may influence policy effectiveness in country-specific contextsHealth Policy20121071839022727243

- HawkesCFood taxes: what type of evidence is available to inform policy development?Nutr Bull20123715156

- WaterlanderWESteenhuisIHde BoerMRSchuitAJSeidellJCIntroducing taxes, subsidies or both: the effects of various food pricing strategies in a web-based supermarket randomized trialPrev Med201254532333022387008

- SmithTALinBHMorrisonRMTaxing caloric sweetened beverages to curb obesityAmber Waves2010832227

- de CastroJMGenetic influences on daily intake and meal patterns of humansPhysiol Behav19935347777828511185

- HasselbalchALGenetics of dietary habits and obesity – a twin studyDan Med Bull2010579B418220816022

- BellCGWalleyAJFroguelPThe genetics of human obesityNat Rev Genet20056322123415703762

- AmarasingheAD’SouzaGObesity Prevention: A Review of the Interactions and Interventions, and some Policy ImplicationsMorgantown, WVWest Virginia University Regional Research Institute2010 Available from: http://rri.wvu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/wp2010-2_Amarasinghe_DSouza_Obesity.pdfAccessed August 13, 2013

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentHealthy choicesPoster presented at: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Health Ministerial MeetingOctober 7–8, 2010Paris, France

- ErvinRBKitBKCarrollMDOgdenCLConsumption of added sugar among US children and adolescents, 2005–2008NCHS Data Brief2012871822617043

- ReidMHammersleyRHillAJSkidmorePLong-term dietary compensation for added sugar: effects of supplementary sucrose drinks over a 4-week periodBr J Nutr200797119320317217576

- ReidMHammersleyRDuffyMEffects of sucrose drinks on macro-nutrient intake, body weight, and mood state in overweight women over 4 weeksAppetite201055113013620470840

- ForsheeRAAndersonPAStoreyMLSugar-sweetened beverages and body mass index in children and adolescents: a meta-analysisAm J Clin Nutr20088761662167118541554

- GibsonSSugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventionsNutr Res Rev200821213414719087367

- BarclayAWBrand-MillerJThe Australian paradox: a substantial decline in sugars intake over the same timeframe that overweight and obesity have increasedNutrients20113449150422254107

- FletcherJSoda taxes and substitution effects: will obesity be affected?Choices2011263

- CrowleJTTurnerEChildhood Obesity: An Economic PerspectiveMelbourneAustralian Government Productivity Commission2010

- World Health OrganizationObesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic Technical Report Series 894GenevaWorld Health Organization2000

- ArancetaJMorenaBMoyaMAnadonAPrevention of overweight and obesity from a public health perspectiveNutr Rev200967Suppl 1S83S8819453686

- SacksGSwinburnBLawrenceMObesity Policy Action framework and analysis grids for a comprehensive policy approach to reducing obesityObes Rev2009101768618761640

- SwinburnBEggerGPreventive strategies against weight gain and obesityObes Rev20023428930112458974

- DietzWHBenkenDEHunterASPublic health law and the prevention and control of obesityMilbank Q2009879121522719298421

- CravenBMMarlowMLShiersAFFat taxes and other interventions won’t cure obesityEconomic Affairs20123223640

- SallisJFGlanzKPhysical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemicMilbank Q200987112315419298418

- FosterGDShermanSBorradaileKEA policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesityPediatrics20081214e794e80218381508

- van ZutphenMBellACKremerPJSwinburnBAAssociation between the family environment and television viewing in Australian childrenJ Paediatr Child Health200743645846317535176

- GolanMWeizmanAFamilial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity: conceptual modeJ Nutr Educ200133210210712031190

- ColbyJJElderJPPetersonGKnisleyPMCarletonRAPromoting the selection of healthy food through menu item description in a family-style restaurantAm J Prev Med1987331711773452355

- WinettRAWagnerJLMooreJFAn experimental evaluation of a prototype public access nutrition information system for supermarketsHealth Psychol199110175782026133

- ChuCDriscollTDwyerSThe health-promoting workplace: an integrative perspectiveAust N Z J Public Health1997214 Spec3773859308202

- VillagraVGAn obesity/cardiometabolic risk reduction disease management program: a population-based approachAm J Med20091224 Suppl 1S33S3619410675

- FrankAA multidisciplinary approach to obesity management: the physician’s role and team care alternativesJ Am Diet Assoc19989810 Suppl 2S44S489787736

- MacLeanLEdwardsNGarrardMSims-JonesNClintonKAshleyLObesity, stigma and public health planningHealth Promot Int2009241889319131400

- VillagraVStrategies to control costs and quality: a focus on outcomes research for disease managementMed Care200442Suppl 4III24III3015026668

- AlemannoACarrenoIFat taxes in the European Union between fiscal austerity and the fight against obesityEuropean Journal of Risk Regulation201124571576

- ShieldsMTremblayMSSedentary behaviour and obesityHealth Rep2008192193018642516

- LajunenHRKeski-RahkonenAPulkkinenLRoseRJRissanenAKaprioJAre computer and cell phone use associated with body mass index and overweight? A population study among twin adolescentsBMC Public Health200772417324280

- FotheringhamMJWonnacottRLOwenNComputer use and physical inactivity in young adults: public health perils and potentials of new information technologiesAnn Behav Med200022426927511253437

- McDonaldCMBaylinAArsenaultJEMora-PlazasMVillamorEOverweight is more prevalent than stunting and is associated with socioeconomic status, maternal obesity, and a snacking dietary pattern in school children from Bogota, ColombiaJ Nutr2009139237037619106320

- Berteus ForslundHTorgersonJSSjostromLLindroosAKSnacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and women compared to a reference populationInt J Obes (Lond)200529671171915809664

- BlockJPHeYZaslavskyAMDingLAyanianJZPsychosocial stress and change in weight among US adultsAm J Epidemiol2009170218119219465744

- De VriendtTMorenoLADe HenauwSChronic stress and obesity in adolescents: scientific evidence and methodological issues for epidemiological researchNutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis200919751151919362453

- HassapidouMFotiadouEMaglaraEPapadopoulouSKEnergy intake, diet composition, energy expenditure, and body fatness of adolescents in northern GreeceObesity (Silver Spring)200614585586216855195

- BrugJvan StralenMMTe VeldeSJDifferences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the ENERGY projectPLoS One201274e3474222558098

- von RuestenASteffenAFloegelATrend in obesity prevalence in European adult cohort populations during follow-up since 1996 and their predictions to 2015PLoS One2011611e2745522102897