Abstract

Background

Torture is an important social and political problem worldwide that affects millions of people. Many host countries give victims of torture the status of refugee and take care of them as far as basic needs; health care, professional reinsertion, and education. Little is known about the costs of torture. However, this knowledge could serve as an additional argument for the prevention and social mobilization to fight against torture and to provide a powerful basis of advocacy for rehabilitation programs and judiciary claims.

Objectives

Development of a model for estimating the economic costs of torture and applying the model to a specific country.

Methods

The estimation of the possible prevalence of victims of torture was based on a review of the literature. The identification of the socioeconomic factors to be considered was done by analogy with various health problems. The estimation of the loss of the productivity and of the economic burden of disease related to torture was done through the human capital approach and the component technique analysis.

Case study

The model was applied to the situation in Switzerland of estimated torture victims Switzerland is confronted with.

Results

When applied to the case study, the direct costs – such as housing, food, and clothing – represent roughly 130 million Swiss francs (CHF) per year; whereas, health care costs amount to 16 million CHF per year, and the costs related to education of young people to 34 million CHF per year. Indirect costs, namely those costs related to the loss of the productivity of direct survivors of torture, have been estimated to one-third of 1 billion CHF per year. This jumps to 10,073,419,200 CHF in the loss of productivity if one would consider 30 years of loss per survivor.

Conclusion

Our study shows that a rough estimation of the costs related to torture is possible with some prerequisites, such as access to social and economic indicators at the country level.

Introduction

Torture is an important and terrible social and political problem. It is a major violation of basic human rights. It affects millions of people around the world.Citation1–Citation4 However, regarding torture, some questions are a matter of debate: how do we define it; how do we measure it; and how do we estimate its impact on individuals and communities?

The United Nations’ Convention against Torture is commonly used to define torture:

Torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.Citation5

This definition, however, raises some conceptual and operational difficulties: 1) it only considers violence inflicted by state representatives, though such violence can be perpetrated by nonstate actors; 2) it only considers severe suffering and pain without defining it more precisely, neither defining the limits between torture and other degrading and inhuman treatments; and 3) it excludes pain and suffering related to lawful sanctions, thus ignoring that nondemocratic states might adopt laws that allow the use of torture.

Thus, there is some semantic ambiguityCitation6 on torture. Yet, its practice is frequent throughout the world, and the situation might even have worsened. In 1973, it was reported from 51% of United Nations’ member states; whereas, in 2003, the proportion was up to 78%.Citation7–Citation10

Most victims of torture present physical as well as psychological sequels, which often leaves them in a fragile situation, both individually and socially. Most victims never get a chance to leave the country of torture; few manage to escape and find refuge in a host country.

Let us keep in mind that in 2010 there was an estimate of 10.5 million United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees-supported refugees worldwide. In addition, 62% lived in ten host countries (Pakistan, 1.9 million; Iran, 1.1 million; Syria, 1 million; Germany, 594,300; and, further down, USA, 265,000; and Great Britain, 238,000).Citation11

Some host countries give victims of torture the status of refugee and take care of them as far as their basic needs, health care, professional reinsertion, and education of children are concerned. This might represent a strain on the host country resources and contribute to the radicalization of migration policies.

Yet few host countries implement a coherent and tough policy condemning torture, nor do they put much pressure on countries where torture is the rule,Citation9,Citation10 leaving it to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to stand up against torture.Citation12 A model for estimating the economic burden of torture for a host country might contribute to a change of attitude in this regard, thus ultimately bringing down torture around the world.

Indeed, a better understanding of the economic cost of torture – which corresponds to the financial charges related to health care and the rehabilitation of victims of torture, but also to the financial charges related to their professional reorientation, to the education of their children, and to their basic needs, such as housing and food – is needed. But the economic cost of torture also includes prevention programs targeting torture, such as the education of potential executioners or of society at-large.

A better understanding of the costs related to torture might also raise strong economic arguments in favor of torture prevention programs and bring torture practice down as much as possible. It would also plead in favor of well-structured rehabilitation programs that allow victims and their families to live a normal life. Furthermore, a better understanding may also help to overcome the impunity of torture-practicing countries and to facilitate the development of rehabilitation programs in host countries.Citation13–Citation15 It might also initiate fairer reparation of victims of torture. Finally, it could possibly promote – on a larger level – the social mobilization of populations and concrete measures of governments against torture.Citation16

We present a model for the estimation of the costs related to torture that a host country of torture victims might face, as well as a case study with data from Switzerland. This has not specifically been done so far,Citation17 although there has been work done on the economics of torture, such as the work of Yakovlev.Citation18

A recent study, conducted by the African Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture Victims of Uganda, which estimated the economic costs related to victims of torture in their own country, demonstrates – using the human capital approach – that the “lost gross output is the major element in the overall loss output, regardless of severity of torture and sex of torture survivor”.Citation19

Methods

Model conception

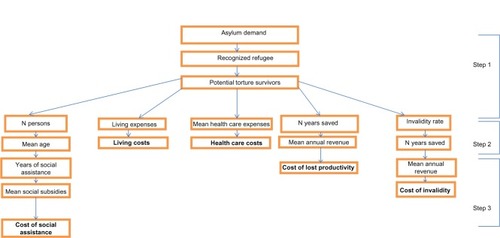

Estimation of prevalence of victims of torture in a host country (step 1)

The estimation of the possible prevalence of victims of torture was based on a review of the literature concerning studies mainly done among refugees seeking asylum in a host country, which prohibits torture.Citation20–Citation23 In our case, the number of potential torture survivors has been estimated on the basis of accepted refugees among the asylum seekers by the Swiss Confederation, as annually reported by the Federal Office of Migration.Citation24 On this population, several economic indicators have been applied, similar to those used to study the economic costs of drug abuse or some chronic diseases.Citation25–Citation30

Identification of socioeconomic indicators to be considered (step 2)

A review of the possible socioeconomic indicators to take into consideration was performed based on the literature investigating various health problems.Citation25–Citation30 The considered economic indicators were the mean age of torture survivors, mean wages, the invalidity rate, and mean living expenses. The sociodemographic indicators are based on the profile of torture survivors followed by the ambulatory service for victims of torture and war of the Swiss Red Cross and of the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics.

Estimation of social and economic costs related to torture (step 3)

The direct costs include the mean daily amount of money the state allocates to the health care costs of asylum seekers. They have been estimated based on the prevalence of torture survivors and their sociodemographic profile.

The indirect costs include the costs related to the loss of productivity and to invalidity. They have been estimated based on the human capital approach, according to which individuals who suffer from a disease or a disability are less productive, more prone to becoming an invalid, and to die early.Citation31–Citation35

Model application: Switzerland’s situation as a case study

These described approaches were applied to data from SwitzerlandCitation24,Citation36–Citation40 to get a global picture of the costs of torture for a host country.

Switzerland’s migration context and its survivors of torture profile

The law of the Asylum Act of June 26, 1998, and modified on July 1, 2013, rules the access to asylum and to the status of refugee, as well as the provisional protection given to those in need. This law defines the refugee as an individual who in his home country or his country of residence is exposed to serious prejudice because of his race, religion, nationality, ethnic, or social group membership. The law makes the distinction between asylum seekers (not yet accepted) and refugees (accepted).

shows the situation in Switzerland over the 2008–2010 period. The countries of origin of asylum seekers vary over time depending on the local social and political conditions. For example, in 2008, there were 17.2% from Eritrea; 12.1% from Somalia; 8.7% from Iraq; 7.8% from Serbia and Kosovo; 7.6% from Sri Lanka; 5.9% from Nigeria; 3.1% from Turkey; 2.9% from Afghanistan; and 2.4% from Iran.

Table 1 Asylum demands and recognized refugees in Switzerland (2008–2010)

In 2001, the situation was quite different: 16% of asylum seekers from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia; 9.4% from Turkey; 6% from Bosnia–Herzegovina; 5.8% from Guinea; 4.3% from Macedonia; and 2.9% from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.Citation41

Roughly 80% of the survivors of torture are males with a mean age of 35 years; 40% have a higher education (vocational or university); 70% have no job; and the proportion of invalids is 10%.Citation42 In addition, the proportion of children is around 35%.Citation42

Results

Model applied to case study

Prevalence of victims of torture in Switzerland

Many authors report that – on average – 30% of refugees in a Western country have been victims of torture in their home country.Citation15,Citation21–Citation23 Their estimation of the number of potential victims of torture is based on the total number of refugees in a given host country. Their socioeconomic characteristics are assimilated to the subgroup of refugees;Citation33 thus, our estimation is of 24,000 refugees on average and 7,200 potential survivors of torture.

Socioeconomic indicators

Estimations of living costs, health care costs, costs related to the education of children, and the invalidity ratio were all based on the data of the administrative sources and on data from the specific studies. Details are given in the section “Case study.”

The mean age, average income, handicap ratio, and amount of money to cover basic needs were all considered as key factors to take into account in the cost estimation, as suggested in the literature considering various health problems.Citation28–Citation30

Estimation of productivity loss and the economic burden of disease

The analysis of the various components of the costs related to torture was adopted and allowed the estimation of the direct and indirect costs – such as loss of productivity, costs of health care, and costs related to education.

Case study

The model was applied to the situation in Switzerland. It was conducted in a three-step sequence.

First, the number of potential victims was determined based on the total average number of refugees in Switzerland over a three-year period from 2008–2010. The number of refugees was established from the data of the Swiss Federal Office for Migration, which examines the request of each asylum seeker and decides to accept him or her as a refugee.Citation33

Second, the basic socioeconomic indicators were determined regarding the various costs to be estimated. The daily cost for basic needs was established on the basis of the average daily allowance for each asylum seeker of the federal state to the cantons. Concerning the living costs, we applied the mean daily allowance the Swiss Federal Government allocates to the cantons for each asylum seeker. For example, this amounted to 55.64 Swiss francs (CHF), according to an official report to the Swiss Federal Committee for Migration.Citation43

Concerning health care costs, we settled on 2,277 CHF, based on several data sources data from the Swiss Federal Office of Migration which puts forward yearly costs of 2,280 CHF per refugee in 2000.Citation24 From a study in the canton of Zurich in 2010, the estimation was 2,445 CHF.Citation40 Costs for the education of the children of the survivors of torture were estimated on the basis of what the costs are for schooling a child per year as published by the Swiss Federal Administration as 13,700 CHF.Citation24

Concerning invalidity, we applied a ratio of 10% based on the data of some authors who proposed 13%.Citation44

Concerning the costs related to nonproductivity (the human capital approach), the amount of healthy productive life-years lost among adult victims of torture was used. The loss of productivity was estimated, taking into account the mean age of victims of torture and the legal age of retirement in Switzerland (65 years for men; 64 for women). Data from the Federal Office of Migration and the Swiss Red Cross Ambulatory Service for Victims of Torture and Warfare reported that only 30% of victims of torture are professionally active and the 10% invalid rate was also taken into account to estimate loss of productivity.Citation24,Citation39,Citation40 Also, we considered the costs related to the education and social integration of the children of victims of torture, ie, considering that 35% of the population of refugees is under 18, considering also the average number of schooling years, and the yearly costs of schooling in Switzerland.

Third, data concerning these indicators have been applied to the sociodemographic characteristics of survivors of torture in Switzerland. The costs are summarized in and . The estimated number of potential survivors of torture (direct victims of torture, eg, proved victims of torture with sequelae, or indirect victims of torture, eg, children of a proved victim of torture) is 7,200 at present in Switzerland; 4,680 of this 7,200 belong to the age group of the active population (>20 and <65 years old), with a mean of 35 years of age. Children, either direct victims of torture or indirect ones, amount to 2,520 ().

Table 2 Basic indicators for cost analysis of torture in host country (Switzerland)

Table 3 Estimated yearly costs related to torture in Switzerland

The costs related to torture can be split into direct costs and indirect costs (). Direct costs, such as housing, food, and clothing, represent roughly 130 million CHF per year, whereas health care costs amount to 16 million CHF per year, and the cost related to education of young people amounts to 34 million CHF per year. Indirect costs, namely those costs related to the loss of productivity of direct survivors of torture, have been estimated to one-third of 1 billion CHF per year. This jumps to 10,073,419,200 CHF in loss of productivity if one would consider 30 years of loss per survivor (mean age, 35 years; age of retirement, 65 years).

Discussion

Prior to any interpretation and utilization of the results of our study, one should keep in mind certain considerations. In any population, there are pathologies that trigger costs for the society. As an example, one might consider the economic costs of brain disorders reported by some authorsCitation45 in the European region in 2010. The total cost of brain disorders was “€798 billion, of which direct health care cost 37%, direct nonmedical cost 23%, and indirect cost 40%; average cost per inhabitant was €5,550”.Citation45

Our study only considers costs related to the formal sector, not taking into account costs that are related to the informal sector; for example, the health care provided to a victim of torture by family members.

The estimation of the costs related to the torture in a host country with a well-developed social system needs to take into account a series of factors, such as: the access to demographic data related to migrant populations, such as refugees and asylum seekers (); economic and social data related to the general population; the access to data related to working conditions, social security, health care organization, and the legal framework regulating social security; and the rights of citizens as well as the situation of asylum seekers and refugees.

Figure 1 Socioeconomic costs of torture: model of cost estimation of survivors of torture in a host country. Costs appear in bold text.

Yet the nature of the indicators used calls for some explanation as well as the sources they are based on: the prevalence of the victims of torture among refugees represents the base on which our model is constructed; the number of asylum seekers and accepted refugees is very country dependent; and various studies have shown important fluctuations. For example, in 2010, there were: 15,567 asylum demands in Switzerland; in France, 52,762 demands were made the same year.Citation24,Citation46 In Switzerland, the estimated number of accepted refugees residing at a given moment in the country is close to 24,000, as reported by the Swiss Federal Office for Migration.Citation24 The prevalence of potential victims of torture among those refugees is estimated at 30% in Switzerland as reported in various studies,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation38 but the data varies from study to study, country to country, and time period to time period.

Masmas et al,Citation47 for example, reported 45% in Denmark. Quiroga et alCitation17 from Sweden report even higher percentages, for example, 51% among a cohort of 2,930 refugees who arrived to the country by air. Thus, the 30% we used in our model is an estimation that might change according to specific situations. This estimation might even be an underestimation. Indeed, the prevalence of victims of torture can vary greatly depending on the country of origin of the survivors as well as the period of time.

The sociodemographic indicators used in our study, such as the age of retirement, the average income, and the percentage of professional activity, are based on data from the Swiss Federal Office for Statistics, the Swiss Forum on Migration Studies, and the Swiss legislation on the age of retirement;Citation24,Citation38,Citation39 those indicators might present some variations when new laws are introduced, for example, or if the age structure of the migrant population was to change drastically or if the economy went down. This has not been the case over the studied period. The differences from one host country to another will, of course, impact costs.

The costs related to the schooling of the children of victims of torture are rough estimates, because there is no specific data on the costs of early integration classes, which those children go to for a few weeks/months before being integrated into normal classes. One should also keep in mind the high percentage of children of foreign origin who are integrated into special classes with more teaching personnel per child and fewer learning objectives. The numbers have been on the increase since 1980 (4% in 1980; 8% in 1996; and 43% in 2004).Citation48,Citation49

Furthermore, torture experiences are difficult to quantify, and the individual responses vary enormously, depending – among many other things – on support from family and friends, on the level of education, and on concrete employment opportunities. These factors, of course, all influence possible costs.

As one can see from these described situations, the developed model for estimating the economic costs of torture in a host country is, therefore, very much country-dependent and in close relation to the legal, social, economic, and humanitarian frameworks of each country. Yet, we consider that our study might be of interest to clinicians, social workers, and politicians in charge of the survivors of torture, even though there are many limits in our approach.

As shown in our case study, the costs related to torture for a host country of the victims of torture could be quite important. Compressing such cost might be possible in some areas, such as health care, through early detection of survivors of torture and through the development of therapy centers that are specialized in the rehabilitation of victims of torture. However, compressing costs related to basic needs (housing, food, clothing) might be more difficult. Indeed, a vast majority of host countries have ratified international protocols and conventions that fix the obligations that states have regarding their citizens, but also migrant populations established on their territory (the Geneva Convention, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, etc), such as ensuring basic needs, but also ensuring the basic education of children or ensuring their access to primary health care.

The loss of productivity of the victims of torture is a major source of indirect costs for a host country. Therefore, professional integration and reorientation of the survivors of torture should be a priority for any host country – all the more that such an approach contributes to the overall well-being of a survivor of torture.Citation39

The economic costs of systematic torture are so enormous that politicians and the international community should integrate them in their discussions on international cooperation and development. Indeed, torture should be part of the negotiation when the financing of cooperation projects is considered – not only out of a human rights perspective but also because of those enormous costs. The states that have instituted torture as a way of governing should be accountable – not only for the cost related to the care and the rehabilitation of victims of torture but also for the costs related to the asylum and the chronic nonproductivity of victims of torture.

According to our estimates, in the case of Switzerland, the annual costs related to the rehabilitation of victims of torture correspond to roughly one-half of the budget allocated to cooperation and development and three times to the budget allocated to the promotion of peace and security worldwide.Citation50 In a more restrictive health perspective, the costs related to the rehabilitation of victims of torture in Switzerland correspond more or less to ten hospitals of reference for 20 million people in an African country.

In our views, torture has a major negative impact on the peace and the development of states where it is systematically practiced, but torture also is responsible for collateral damage in the host countries of the victims of torture. These host countries could and should consider the states practicing torture as fully accountable for such a situation.

Torture could even represent much higher costs, should intangible costs related to chronic pain be taken into consideration (which we did not consider in our study). Indeed, it is well-known that victims of torture very often suffer from chronic pain related to various psychological and physical sequels.Citation51 In the literature, authors report between 63%–80% of victims of torture who suffer from long-lasting chronic pain that needs specific care.Citation52,Citation53 One should keep in mind that one single chronic pain patient (all pathologies included) represents yearly costs related to health care of 5,665 CHF (twice as high in the case of elevated depression scores), as reported from Ireland,Citation54 or that 61% of people with chronic pain have trouble holding a job, as reported in a European study.Citation55

But it could be argued that taking well-integrated and healthy individuals as a baseline for comparison of costs to the social system of a country is a biased view and artificially raises global social costs of survivors of torture; perhaps it would be more reasonable to consider as a baseline controls with similar life courses except for torture. This is an interesting argument that indeed can be made. We took the option in our case study to compare the survivors of torture to the general population, since data of the Swiss Red Cross shows that survivors of torture were previously rather well-integrated and educated individuals in their home countries.Citation22,Citation38

What could help in reducing the costs of torture? Prevention surely could. Indeed, costs could be easily reduced if prevalence and incidence of torture were to come down throughout the world, especially in countries where torture is very common.

Nonetheless, let’s consider some limits of our approach. One limiting factor might be the various existing definitions of torture: from straightforward torture to nonhuman treatment, such as psychological manipulation, though someCitation44,Citation56 – who have worked in extreme situations in former Yugoslavia – have come to the conclusion that both cause much suffering and, therefore, might be considered as similar. Another critical point that might greatly affect the global cost estimations of victims of torture in a host country is the estimation of the number of victims of torture, based on the number of accepted and officially recognized refugees, a number that represents 10%–20% of asylum seekers in Switzerland over the past decadeCitation33 and 1%–39% among the European Union member countries in 2007.Citation52

The estimation of health care costs might also be difficult since often health care costs are not specifically identified for legally recognized refugees but rather for asylum seekers, as is the case in Switzerland.Citation32 The estimation of the costs related to basic needs, such as housing, clothing, and food, might also heavily be influenced by local factors, as it is the case in Switzerland where important differences between cantons (from 320–768 CHF per person per month) have been reported by the Swiss Federal Commission on Migration.Citation37 Furthermore, no estimation of intangible costs – such as the ones related to physical pain or psychological distress – have been considered in our study, though pain and psychological distress are certainly major problems to survivors of torture.Citation52

We are aware that the results of our study might be used in different ways. Some might use them to justify restrictive migration policies; this is by no means our position. Others might consider these results as a basis for the development of specific care services for victims of torture as well as a strong argument in favor of the fight against torture, an approach we share.

Conclusion

It has been argued that the complexity of the practice of torture, the variety of health problems related to torture, the different approaches in taking care of victims of torture, the huge differences in wealth among countries, and the variety of economic problems among host countries are major obstacles to the estimation of costs related to torture.

Our study shows that a rough estimation of such costs is possible with some prerequisite, such as the access to social and economic indicators at the country level.

On a more political level, our study should be considered as a plea to host countries to get more strongly and deeply involved in the prevention and elimination of torture – and not as a possible justification in discouraging and refusing refugee claims.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Swiss Red Cross Ambulatory Service for Victims of Torture and Warfare for its help.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MoisanderPAEdstonETorture and its sequel–comparison between victims from six countriesForensic Sci Int20031372–313314014609648

- ScottRGThe History of Torture Throughout the AgesWhitefish, MontanaKessinger Publishing2003

- DaudASkoglundERydeliusPAChildren in families of torture victims: transgenerational transmission of parents’ traumatic experiences to their childrenInternational Journal of Social Welfare20051412332

- EinolfCJThe Fall and Rise of Torture: A Comparative and Historical AnalysisSociological Theory2007252101121

- un.org [homepage on the Internet]Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ResolutionUnited Nations General Assembly1984 Available from: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/39/a39r046.htmAccessed March 2, 2013

- GreenDRasmussenARosenfeldBDefining torture: a review of 40 years of health science researchJ Traumatic Stress2010234528531

- Amnesty InternationalCombating Torture: A Manual for ActionLondonAmnesty International UK2003

- MpingaEKZesigerVArzelBGolayMChastonayPDe l’épidémiologie à la réhabiltation des victimes des tortures: quels rôles pour les professionnels de santé [The epidemiology of rehabilitation of the victims of torture: roles for health professionals]Bulletin des Médecins Suisses2005861810861089 French

- ConradCRMooreWHWhat Stops the Torture?American Journal of Political Science2010542459476

- WelchMThe re-mergence of torture in political culture: tracking its discourse and genealogyCapítulo Criminológico: Revista de las Disciplinas del Control Social2007354471505

- HristovaMAnalyse démographique des demandeurs d’asile et des réfugiés au Canada (2000–2010) [Demographic analysis of asylum seekers and refugees in Canada (2000–2010)] [master’s thesis]MontréalUniversity of Montréal2012 French

- FarissCJSchnakenbergKEA Human Rights Network Influences Countries’ Torture Policies: Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 3–6 September 2009New York, NYCambridge University Press2009

- Hjorth-MadsenMThe cost of coherence: the case of EU-funding for rehabilitation of torture victimsTorture20051515158

- RodleyNSecuring, redress and overcoming immunity – some reflectionsThe International Journal of Human Rights2012165691693

- van BovenTThe need to repairThe International Journal of Human Rights2012165694697

- EcheverriaGDo victims of torture and other serious human rights violations have an enforceable right to reparation?The International Journal of Human Rights2012165698716

- QuirogaJJanransonJMPolitically motivated torture and its survivors: a desk study review of the literatureTorture2005162–31112

- YakovlevPThe economics of tortureCoyneCJMathersRLThe Handbook on the Political Economy of WarNorthampton, MAEdward Elgar Publishing2011109125

- MaswereWDWamonoFEstimating the Socio Economic Effects of torture in UgandaAfrican Centre for treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture VictimsKampala2013 Available from: http://www.actvuganda.org/sites/default/files/Estimating%20the%20Socio-Economic%20Effects%20of%20Torture%20in%20Uganda_ACTV-March%202013.pdfAccessed June 13, 2013

- van der VeerGCounselling and Therapy with Refugees and Victims of Trauma: Psychological Problems of Victims of War, Torture and Repression (Wiley Series in Psychotherapy and Counselling)New YorkJohn Wiley and Sons1992

- WickerHRDie Sprache Extremer Gewalt: Studie Zur Situation von gefolterten Flüchtlingen in der Schweiz und zur Therapie von Folterfolgen [The Language of Extreme Violence: Study on the situation of tortured refugees in Switzerland and on the treatment of torture consequences]BernInstitute of Ethnology, University of Bern1993 German

- FreyCLe traitement des Victimes des Tortures et des Victimes de Guerre en exil: Premières Expériences du Centre de Thérapie CRS [The treatment of victims of torture and victims of warfare in exile: first experiences of the Center of Therapy CRS]Bulletin des Médecins Suisse1998S52S58 French

- BakerRPsychosocial consequences for tortured refugees seeking asylum and refugee status in EuropeBasogluMTorture and its Consequences: Current Treatment ApproachesCambridgeCambridge University Press200383106

- OFM, Office Fédéral des migrationsStatistique du domaine de l’asile. Rapports annuels Available from: http://www.bfm.admin.ch/content/bfm/fr/home/dokumentation/zahlen_und_fakten/asylstatistik/jahresstatistiken.htmlAccessed December 12, 2012

- CollinsDJLapsleyHMThe Costs of Tobacco, Alcohol and Illicit Drugs Abuses in Australian SocietyCanberraCommonweatlh of Australia2008 Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/34F55AF632F67B70CA2573F60005D42B/$File/mono64.pdfAccessed April 13, 2013

- American Diabetes AssociationEconomic costs of diabetes in the US in 2007Diabetes Care200831359661518308683

- WimoAWinbladBJönssonLThe worldwide societal costs of dementia: Estimates for 2009Alzheimers Dement2010629810320298969

- SolomonSDDavidsonJRTrauma: prevalence, impairment, service use, and costJ Clin Psychiatry199758Suppl 95119329445

- LebrunTSelkeBL’évaluation du coût social de l’alcoolisme en France [Evaluation of the social cost of alcoholism in France]Actualité et Dossier en Santé Publique20043467780 French

- PatraJPopovaSRehmJBondySFlintRGiesbrechtNEconomic cost of chronic disease in Canada 1995–2003OntarioPublic Health Agency2007 Available from: http://www.cdpac.ca/media.php?mid=260Accessed May 5, 2013

- LandefeldJSSeskinEPThe economic value of life: linking theory to practiceAm J Public Health19827265555666803602

- HutubessyRCvan TulderMWVondelingHBouterLMIndirect costs of back pain in the Netherlands: a comparison of the human capital method with the friction cost methodPain1999801–220120710204732

- GoereeRO’BrienBJBlackhouseGAgroKGoeringPThe valuation of productivity costs due to premature mortality: a comparison of the human-capital and friction-cost methods for schizophreniaCan J Psychiatry199944545546310389606

- HoganPDallTNikolovPAmerican Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002Diabetes Care200326391793212610059

- ShlensJA Tutorial on Principal Component Analysis. Derivation, Discussion and Singular Value DecompositionSystems Neurobiology LaboratoryUniversity of California at San Diego2003 Available from: http://www.cs.princeton.edu/picasso/mats/PCA-Tutorial-Intuition_jp.pdfAccessed March 19, 2012

- PiguetEMistelliRL’intégration des requérants d’asile et des refugiés sur le marché du travail [Integration of applicants for asylum and refugees into the labor market]NeuchâtelForum Suisse pour l’etude des migrations1996 French

- WichmannNHermannMD’AmatoGLes marges de manoeuvre au sein du fédéralisme: la politique de migration dans les cantons [Room for maneuver in the heart of federalism: canton migration policy]ZurichCommission fédérale pour les questions de migration CFM2011 Available from: https://www.ekm.admin.ch/content/dam/data/ekm/dokumentation/materialien/mat_foederalismus_f.pdfAccessed April 15, 2013

- Croix-Rouge Suisse, Service Ambulatoire pour les Victimes de Tortures et de GuerreRapport Annuel 2011 [Annual Report 2011]BerneCroix-Rouge Suiss2012 French

- GerberACL’intégration professionnelle des réfugiés en Suisse: situation en 2000 [Professional integration of refugees in Switzerland] [master’s thesis]GenevaUniversité de Genève2008

- MaierTSchmidtMMuellerJMental health and health care utilization in adult asylum seekersSwiss Med Wkly2010140w1311021104473

- FibbiRPolitique d’asile et questions migratoires [Asylum policy and migration issues]Annuaire Suisse de Politique de Développement2008271197217

- Croix-Rouge Suisse, Service Ambulatoire pour les Victimes de Tortures et de GuerreStatistiques 2011 [Statistics 2011]BerneCroix-Rouge Suiss2012 French

- OFS Office fédéral de la statistiqueAnnuaire statistique de la Suisse [Swiss Annual Statistics]BerneHans Huber Verlag2009 Available from: http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/dienstleistungen/publikationen_statistik/statistische_jahrbuecher/stat__jahrbuch_der.htmlAccessed December 20, 2012

- ŠpiricZKneževicGThe socio-demographic and psychiatric profiles of clients in the centre for rehabilitation of torture victims- IAN BelgradeŠpiricZKneževicGJovicVOpacicGTorture in War: Consequences and Rehabilitation of Victims – Yugoslav ExperienceBelgrade, SerbiaInternational Aid Network2004121152

- OlesenJGustavssonASvenssonMWittchenHUJönssonBCDBE2010 study group; European Brain CouncilThe economic cost of brain disorders in EuropeEur J Neurol2012191152162

- OFPRA Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatridesRapport d’activité 2011 [Activity report 2011] Available from: http://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/documents/OfpraRA2011.pdfAccessed April 13, 2013

- MasmasTNMøllerEBuhmannrCAsylum seekers in Denmark – a study of health status and grade of traumatization of newly arrived asylum seekersTorture2008182778619289884

- OFS Office fédéral de la statistiqueIntégration: une histoire d’échecs? Les enfants et les adolescents étrangers face au système Suisse de formation [Integration: a failure story? Children and teenagers confronted by the Swiss education system]BerneOffice fédéral de la statistique1997 French

- OFM, Office fédéral des migrationsProblèmes d’intégration des ressortissants étrangers en Suisse [Integration problems of foreigners in Switzerland]BerneOffice fédéral des migrations2006 Available from: http://www.ejpd.admin.ch/content/dam/data/kriminalitaet/jugendgewalt/ber-integration-bfm-f.pdfAccessed June 2, 2013

- Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDCAnnual Report 2011BerneSwiss Agency for Development and Cooperation2011 Available from: http://www.sdc.admin.ch/en/Home/Documentation/Publications/Annualreports/Annual_reports_archiveAccessed December 12, 2012

- CarinciAJMehtaPChristoPJChronic pain in torture victimsCurr Pain Headache Rep2010142737920425195

- ThomsenABEriksenJSmidt-NielsenKChronic pain in torture survivorsForensic Sci Int2000108315516310737462

- WilliamsACPeñaCRRiceASPersistent pain in survivors of torture: a cohort studyJ Pain Symptom Management2010405715722

- RafteryMNRyanPNormandCMurphyAWde la HarpeDMcGuireBEThe economic cost of chronic noncancer pain in Ireland: results from the PRIME study part 2J Pain201213213914522300900

- BreivikHCollettBVentafriddaVCohenRGallacherDSurvey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatmentEur J Pain200610428733316095934

- BaşoğluMLivanouMCrnobarićCTorture vs other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment: is the distinction real or apparentArch Gen Psychiatry200764327728517339516