Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease and the most common form of dementia in elderly people. It is an emerging public health problem that poses a huge societal burden. Linkage analysis was the first milestone in unraveling the mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 that cause early-onset AD, followed by the discovery of apolipoprotein E-ε4 allele as the only one genetic risk factor for late-onset AD. Genome-wide association studies have revolutionized genetic research and have identified over 20 genetic loci associated with late-onset AD. Recently, next-generation sequencing technologies have enabled the identification of rare disease variants, including unmasking small mutations with intermediate risk of AD in PLD3, TREM2, UNC5C, AKAP9, and ADAM10. This review provides an overview of the genetic basis of AD and the relationship between these risk genes and the neuropathologic features of AD. An understanding of genetic mechanisms underlying AD pathogenesis and the potentially implicated pathways will lead to the development of novel treatment for this devastating disease.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Currently, there are ~46.8 million dementia cases worldwide, with that number projected to reach 74.7 million in 2030 and over 131.5 million by 2050.Citation1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major public health problem in the world. Health care costs of dementia in 2015 surpassed $818 billion (USD), and this figure is estimated to be as high as $2 trillion by 2030.Citation1 AD is the most common form of dementia and one of the most common diseases in the developed countries. AD is defined clinically by gradual decline in memory and progressive loss of cognitive functions. Neuropathologically, AD is characterized by gross cortical atrophy and ventricular dilatation and pathological hallmarks of accumulation of Aβ protein in the form of senile plaques and intraneuronal tangles of hyperphosphorlylated tau (t) protein. AD is a multifactorial and complex disease and leading cause of dementia among elderly people. Although advanced age is the best known risk factor for AD, some individuals may develop AD at younger age. Hence, based on the time of onset, AD is classified into two types.Citation2 Early-onset AD (EOAD), which typically develops before the age 65 years, and late-onset AD (LOAD) in those older than 65 years. EOAD is caused by rare and dominantly inherited mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2. LOAD has a strong genetic component, and it is also called sporadic AD. Up to 60%–80% of LOAD is inheritable, but genetic and environmental factors play a key role in onset, progression, and severity of disease.Citation3

The ε4 allele of the APOE gene is the major risk factor for pathogenesis of LOAD.Citation4,Citation5 Using revolutionizing technologies such as genome-wide association study (GWAS), researchers have identified a number of regions of interest in the genome that may increase a person’s risk for LOAD to varying degrees.Citation6,Citation7 Furthermore, next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have identified rare susceptibility modifying alleles in different AD genes.Citation8 However, other causative and risk genes are involved in AD and need to be identified to fully elucidate the etiology of AD. In this review, we provide a summary of the genetic basis of both EOAD and LOAD, the relationship between these risk genes and the pathogenesis of AD.

Types of studies in AD genetics

Mainly four strategies have governed the field of AD genetics: genetic linkage analysis, study of candidate genes, GWASs, and NGS technology. Genetic linkage family studies have led to the identification of dominantly inherited, rare mutations in genes of EOAD (APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2). The development of whole-genome genotyping by several independent GWASs has allowed for the study of the involvement of common variants with low risk in disease.

Genetic linkage analysis

Linkage analysis was the first milestone in unraveling the genetic basis of AD studies of families displaying autosomal dominant inheritance. Genetic linkage studies aim to identify chromosomal regions associated with disease but do not identify one gene or one mutation associated with a disease. Genetic linkage studies in families led to the identification of dominantly inherited mutations in APP on chromosome 21q, PSEN1 on 14q, and PSEN2 on 1q that are associated with EOAD.Citation9 The ε4 allele of the APOE, which is considered as only one genetic risk factor for LOAD, was also identified with the help of genetic linkage studies.Citation10 Nonetheless, linkage mapping has been very useful in identifying monogenic traits in EOAD, but it has largely failed to identify risk factors in LOAD, probably due to the complex trait with unidentified variants.

Study of candidate genes

In candidate gene studies, genetic variants of people with a particular disease are genotyped and compared with a similar group of healthy individuals. Susceptibility genes are revealed when case and control frequencies differ significantly. Candidate gene approach elucidated that APOE risk alleles are firmly implicated in LOAD. Over 1,000 candidate genes were tested for AD susceptibility, with mostly inconsistent results. The success of this approach relies on the existing knowledge on disease pathogenesis. Because of small sample size, inadequately evaluated population groups, and insufficient P-value threshold, most of the candidate studies could not be replicated.Citation11

Genome-wide association studies

The development of microarray technology revolutionized genetics research, allowing for the simultaneous evaluation of millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in thousands of samples. Such cheap and comprehensive GWAS allows one to perform genome-wide association testing in a hypothesis-free manner. Besides APOE, GWAS has allowed identification of >20 genetic loci associated with increased susceptibility for LOAD.Citation12 GWAS has successfully identified numerous susceptibility genes for AD, but, rare variants will not be detectable by GWAS. Thus, the success of GWAS depends on sample size, frequency of risk alleles, and individual effect sizes.

NGS technologies

NGS technologies provide fast and cost-effective sequencing strategies that allow an entire genome to be sequenced in <1 day. NGS technology has important implications in understanding the basis of many Mendelian neurological conditions and complex neurological diseases that have enabled the identification of rare disease variants, including unmasking small mutations. Recently, NGS has been applied to identify genetic factors in small families with unexplained EOAD. The primary success of NGS in AD has been the identification of rare susceptibility modifying alleles in APP, TREM2, and PLD3.Citation8

EOAD susceptibility genes

Studies of families with autosomal dominant patterns of inheritance were a cornerstone in understanding the genetics of AD. Three genes are considered the main risk factors for EOAD: APP on chromosome 21q, PSEN1 on 14q, and PSEN2 on 1q that are associated with EOAD (). To date, >270 highly penetrant mutations have been described in these genes that cause familial AD and many more are discovered each yearCitation13 (http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/admutations/).

Table 1 Genes implicated in risk of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

APP

The gene encoding APP is located on chromosome 21q21.3. The three isoforms, APP751, APP770, and APP695, are produced by splicing of APP. The major isoform found in brain is APP695.Citation14 APP is proteolytically cleaved following nonamyloidogenic or amyloidogenic pathway by three enzymes, known as α-, β-, and γ-secretases. Proteolysis of APP by α- and γ-secretases results in nonpathogenic fragments (sAPPα and α-C-terminal fragment) in non-amyloidogenic pathway. In the amyloidogenic pathway, proteolysis of APP by β-secretase and γ-secretase results in two major Aβ species that include sAPPβ and β-CTF.Citation15 The action of γ-secretases on β-CTF generates Aβ, which forms a key component of amyloid plaques known as extracellular fibrils in AD brain.Citation16 To date, 49 APP mutations in 119 families are known to cause AD.Citation13 Most of the APP mutations are dominantly inherited but two recessive mutations, A673V and E693Δ have been reported to cause EOAD.Citation17 The clustering of most pathogenic APP mutations either adjacent to or within the cleavage sites of β- and γ-secretase (exons 16 and 17 of APP) shows that they might be involved in AD pathogenesis.Citation13,Citation18 Swedish APP Mutation (KM670/671NL) is a double point mutation located at the N-terminus of the Aβ domain adjacent to the β-secretase site in which lysine–methionine is replaced by asparagine–leucine. In Swedish mutation, total Aβ level increases by twofold to threefold, thus affecting the efficiency of β-secretase cleavage.Citation19 In a case with Swedish mutation, autopsy revealed cortical atrophy, enlargement of the cerebral ventricles, and sulcal widening. Studies have shown that patients with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) develop AD pathology earlier than the normal person.Citation17,Citation20 Thus, AD pathology may be related to overexpression of APP. Along with Swedish APP Mutation, Tottori mutation (Asp678Asn) and Leuven mutations (Glu682Lys) are located at the N-terminus of the Aβ domain adjacent to the β-secretase site. London mutation (V717I) is one of the most common APP mutations worldwide. APP mutation at or after C-terminus of the Aβ domain alters the γ-secretase function with increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio by increasing Aβ42 levels and decreasing Aβ40 levels. Neuropathological findings in an English family were cortical Lewy bodies and mild amyloid angiopathy. β-Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangle were found in the American family, with the absence of amyoid angiopathy or Lewy bodies.Citation21 Arctic mutation (E693G) occurs in the coding region of Aβ domain. This mutation fails to alter total Aβ level or the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40. Arctic mutation results in increased aggregation rate of mutant peptide.Citation22 Brain imaging showed no signs of strokes or vascular lesions but neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles consistent with a diagnosis of AD were seen in one mutation carrier.Citation23 Flemish mutation (A692G) falls within the region of Aβ domain and increases the level of Aβ42 and Aβ40 by twofold to fourfold, affecting γ-secretase activity for Aβ production. Flemish mutation results in Aβ deposition in the blood vessels of the brain and senile plaques.Citation24 Jonsson et alCitation25 found a rare mutation (A673T) in the APP gene that showed a strong protective effect against AD.

Abovementioned examples show that altered APP processing and Aβ accumulation are key in the AD pathogenesis.

PSEN1

PSEN1 gene is located on chromosome 14q24.3, and it is a vital component of the γ-secretase complex, which cleaves APP into Aβ fragments. PSEN1 is localized primarily to the endoplasmic reticulum and helps in protein processing. To date, 215 pathogenic mutations have been identified in PSEN1, of which >70% mutations occur in exons 5, 6, 7, and 8.Citation13 Mutations in PSEN1 account for up to 50% of EOAD, with complete penetrance and early age of onset. Mutant γ-secretase increases Aβ42 level while it decreases Aβ40 level, leading to an increase in the Aβ 42/40 ratio. Studies have shown that Aβ42 is more amyloidogenic and more prone to aggregate in brain than Aβ40.Citation9,Citation26,Citation27 Morphologic variants in Aβ plaques due to PSEN1 mutations may result in cotton wool plaques. Cotton wool plaque is formed by large rounded Aβ deposits, and it tends to be immunopositive for Aβ42 rather than for Aβ40.Citation28–Citation30 The vast majority of PSEN1 mutations are missense mutations, but a few insertion and deletions have also been detected. Neuronal loss of 30% in the hippocampal CA1 region, decreased synaptic plasticity, and 18% of hippocampus atrophy was demonstrated by Breyhan et alCitation31 due to the intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ peptides and fibrillary accumulation species. In addition to their role in γ-secretase activity, PSEN1 mutations may compromise neuronal function, affecting GSK-3β activity and kinesin-I-based motility, thus leading to neurodegeneration.Citation32

PSEN2

PSEN2 gene is located on chromosome 1q31-q42, and it is very similar in structure and function to PSEN1. PSEN2 mutations are very rare, and to date 13 pathogenic PSEN2 mutations have been detected in 29 families.Citation13 PSEN2 is a main component of the γ-secretase complex along with PSEN1, nicastrin, Aph-1, and PEN-2.Citation33 PSEN2 mutation alters the γ-secretase activity and results in increase in the Aβ 42/40 ratio in similar manner to the PSEN1 mutation.Citation9,Citation26,Citation27 PSEN2 mutations carriers have older age of onset with a wide range from 39 years to 75 years. Neuritic plaque formation and neurofibrillary tangle accumulation may be seen as neuropathological changes in some people with PSEN2 mutations.Citation34 Park et alCitation35 demonstrated that β-secretase activity is enhanced by PSEN2 mutation, through reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Although, PSEN2 shows close homology to PSEN1, but less amyloid peptide is produced by PSEN2.Citation36

LOAD susceptibility genes

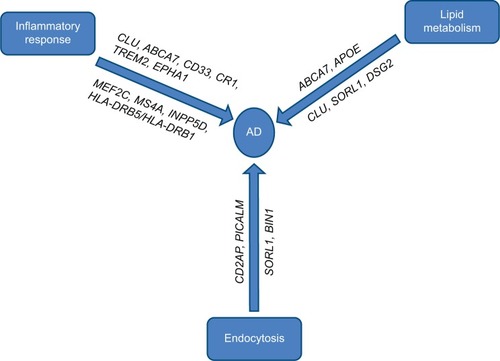

LOAD is genetically far more complex than EOAD with the possible involvement of multiple genes and environmental factors. Most LOAD cases are sporadic with no family history of the disease. Before the era of large-scale GWAS, ε4 allele of the APOE gene was the only well-established risk factor for the pathogenesis of LOAD, but with technological advances, researchers have identified a number of regions of interest in the genome that may increase a person’s risk for LOAD to varying degrees. It was striking to note that most of the genes identified by GWAS that could be linked with the Aβ cascade or tau pathology roughly cluster within three pathways (). We will briefly describe the known genes of LOAD, biological pathways, and mechanisms that might be relevant to AD biology.

Genes involved in cholesterol metabolism

The genes implicated in cholesterol metabolism are APOE, SORL1, ABCA7, and CLUCitation6,Citation37–Citation39 (). Solomon et alCitation40 demonstrated that having high cholesterol levels in midlife increased the risk of developing AD in late life.

Table 2 Common and rare variants associated with Alzheimer’s disease

APOE gene

The APOE gene, located on chromosome 19q13.2, is the strongest genetic risk factor for LOAD. APOE protein is the major cholesterol carrier in the brain. There are three common alleles of APOE called ε2, ε3, and ε4 alleles. APOE ε4 increases LOAD risk, whereas APOE ε2 is associated with decreased LOAD risk.Citation41–Citation44 There is a threefold increased risk of AD by one copy of APOE ε4 and 12-fold by two APOE ε4 alleles. APOE is involved in the control of inflammation, cholesterol metabolism, lipid transport, synaptic function, neurogenesis, or the generation and trafficking of APP and Aβ.Citation45–Citation47 In the study of large Colombian kindred, APOE ε4 was associated with earlier onset of dementia in individuals with PSEN1 mutation.Citation48 More recently, Vélez et alCitation49 reported ApoE2 allele delays age of onset for carriers of the Paisa mutation (PSEN1 E280A). The mechanism that underlies the link between APOE4 genotype and AD is complex. Studies in humans and transgenic mice showed that APOE influences Aβ clearance, aggregation, and deposition in an isoform-dependent manner.Citation50–Citation52 Studies suggest that ApoE4 inhibits Aβ clearance and is less efficient in mediating Aβ clearance compared with ApoE3 and APOE2. ApoE4 also contributes to AD pathogenesis by Aβ-independent mechanisms that involve synaptic plasticity, cholesterol homeostasis, neurovascular functions, and neuroinflammation. In APOE4 carriers, there is accelerated Aβ deposition as senile plaques compared with noncarriers.Citation53,Citation54 Recently, Dorey et alCitation55 showed that APOE isoforms differentially regulate and modify the Aβ-induced inflammatory response in neural cells in AD, with ApoE2 suppressing and ApoE4 promoting the response. Levels of total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 181 were increased in AD patients who were APOE4 homozygotes.Citation56 Conversely, lower cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) p-tau and t-tau concentrations and decreased rate of hippocampal atrophy were seen in APOE2 carriers. This shows that APOE ε2 is associated with decreased AD pathology.Citation57 APOE2 has higher affinity for Aβ than does APOE4.Citation58 Therefore, APOE2 may be more efficient than APOE4 at clearing Aβ fragments from the extracellular space.Citation59 Neuroimaging study of APOE ε4 carriers showed gray matter volume decline with age, elevated hippocampal atrophy, increased amyloid load, impaired glucose metabolism, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy with increased microbleeds.Citation60–Citation63

CLU

The clusterin (CLU) gene has been identified as an important risk locus for AD in more than two GWASs.Citation37,Citation64 In these GWASs, three SNPs within CLU (rs11136000, rs2279590, and rs9331888) showed statistically significant association with AD. CLU, also known as apolipoprotein J, is an apolipoprotein that is widely expressed in both the periphery and the brain.Citation65 CLU is situated on chromosome 8p21-p12. CLU is hypothesized to act as an extracellular chaperone that plays an important role in lipid transport, complement regulation, apoptosis, sperm maturation, endocrine secretion, and membrane protection.Citation66,Citation67 AD patients have elevated levels of CLU in the frontal cortex and hippocampus.Citation68 CLU concentration is increased in the CSF of patients with AD, suggesting its utility as a prognostic or diagnostic biomarkers in AD. Plasma CLU level was shown to be linked with brain atrophy, disease severity, and clinical progression in AD patients. AD patients with increased CLU mRNA expression deteriorate faster than normal.Citation69,Citation70 Similar to APOE, CLU is present in amyloid plaques, binds to Aβ peptides, and interacts with Aβ40 and Aβ42. Thus CLU might play an important role in AD pathology. Recently, Deming et alCitation71 found that CLU levels were significantly associated with AD status and CSF tau/Aβ ratio, thus influencing the immune system and neurogenesis in AD. CLU suppresses Aβ deposition, inhibits the complement system to prevent inflammation, and decreases apoptosis and oxidative stress in AD. These findings generally support a biochemical role for CLU in the development of AD pathogenesis.

ABCA7

ABCA7, located on chromosome 19p13.3, has recently been identified as a strong genetic locus associated with LOAD in GWASs.Citation37,Citation72 ABCA7 is a member of the ATP-binding cassette genes, and its expression was detected in hippocampal and microglia cells in the brain.Citation73 ABCA7 mediates transport of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, effluxes lipids from cell into lipoprotein particle, and generates phospholipids. It can also play a vital role in cholesterol homeostasis and the immune system. Meta-analyses of all data provided compelling evidence that SNPs rs3752246 and rs3764650 near ABCA7 have been associated with LOAD.Citation38,Citation74 Recently, ABCA7 variant SNP (rs115550680) was found to nearly double the risk of LOAD in African-Americans.Citation75 ABCA7 also regulates phagocytosis by macrophage uptake of Aβ and mediates processing of APP.Citation76,Citation77 The recent study by Steinberg et alCitation78 in Icelandic population identified ABCA7 as the most significant gene for AD. Studies in adult mice showed that ABCA7 is expressed most abundantly by macrophages (ie, tenfold higher than neurons), and Aβ is accumulated in brain of ABCA7-deficient mice.Citation76 Emerging data suggest that ABCA7 could be associated with AD via various pathways, possibly including Aβ accumulation, lipid metabolism, and phagocytosis.

SORL1

SORL1 (also known as SorLA and LR11) is located on chromosome 11q23.2-q24.2, and it is a member of the Vsp10p domain receptor family and is involved in intracellular transport and processing of APP, resulting in decreased production of Aβ peptide.Citation79,Citation80 Although the actual functional risk loci within the SORL1 gene still remain unknown, studies have showed that SORL1 plays a key role in AD susceptibility.Citation81–Citation83 Disruption of SORL1 has also been shown to influence Aβ pathway and tau-related cellular processes.Citation84,Citation85 Significant associations between SORL1 genetic variants and AD have been reported in several ethnic groups.Citation86,Citation87 SORL1 risk variants have also been associated with hippocampal atrophy, and altered CSF Aβ level, suggesting its potential role in LOAD pathogenesis.Citation88 The current data suggest that underexpression of SORL1 leads to overexpression of Aβ, which has been associated with a higher risk of developing AD.Citation84,Citation89 SORL1 also mediates APP processing via endocytotic pathways and plays a key role in Aβ production.Citation84 Meta-analysis of the association between variants in SORL1 and AD has identified that SNP rs12285364 was significantly associated with increased risk of AD.Citation90

Genes involved in immune response

Involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of LOAD was revealed in several GWASs. Neuroinflammation is a pathological hallmark of AD. LOAD genes implicated in immune response are CR1, CD33, MS4A, ABCA7, EPHA1, TREM2, and CLUCitation6,Citation37–Citation39,Citation72 ().

CR1

CR1 (also known as C3b/C4b receptor or CD35) is located on chromosome 1q32, and it is a member of the receptors of complement activation family. CR1 is a single-chain type I transmembrane glycoprotein comprising four main structural domains and mainly expressed on erythrocytes, leukocytes, and splenic dendritic cells.Citation91 CR1 acts as a receptor in classical pathway and alternative pathway; CR1 on phagocytes facilitates the uptake and removal of immune complexes; CR1 components have neuroprotective effect in AD. Thus, CR1 functions as a complement regulatory protein and helps in immune regulation.Citation92,Citation93 In recent GWASs, SNPs in CR1 have been associated with LOAD risk.Citation38,Citation64,Citation72 It has been reported that SNPs rs3818361 and rs6656401 in CR1 are associated with increased risk of AD.Citation64 SNP rs1408077 was associated with plaque load in the brain of patients with AD.Citation94 The deposition of smaller local gray matter volume in the entorhinal cortex of carriers of the CR1 rs6656401 might lead to an increased risk of AD later in life.Citation95 CR1 plays a key role in AD pathogenesis via reducing activation of complement cascade activity. CR1 variant is associated with increased CSF Aβ42 levels, and some variants lead to vascular amyloid deposition.Citation96,Citation97 CR1 mRNA is involved in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and thus results in cognitive decline.Citation70

CD33

CD33 is located on chromosome 19q13.3, and it is a type I transmembrane protein, which belongs to the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins, and it is expressed on myeloid cells and microglia. CD33 plays an important role in mediating cell–cell interaction, facilitates clathrin-independent endocytosis, inhibits immune cell functions, and regulates cell growth and survival, via induction of apoptosis.Citation98,Citation99 Recent GWASs have identified CD33 as a strong genetic locus associated with LOAD. The two SNPs at the CD33 gene cluster, rs3865444 and rs3826656, have been associated with LOAD.Citation39,Citation72 In AD patients, the minor allele of the CD33 SNP rs3865444 was associated with reductions in both CD33 level and amyloid plaque burdens in the brain.Citation100 There is positive correlation between CD33 expression in microglia with plaque burden and declined cognitive function. Bradshaw et alCitation101 demonstrated that the CD33 risk allele rs3865444 increases CD33 expression in monocytes and is associated with increased amyloid pathology in patients with AD. CD33 contributed to the pathogenesis of LOAD by impairing microglia-mediated clearance of Aβ. Furthermore, the increased Aβ clearance and reduced Aβ levels in vitro and in vivo are due to deletion of CD33.

MS4A

The MS4A gene is located on chromosome 11q12.2, and it encodes protein that contains at least four potential transmembrane domains, two extracellular loops with cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domain, and one intracellular loop. MS4A genes are highly expressed in hematopoietic cells such as myeloid cells and monocytes. Although MS4A genes are poorly characterized, MS4A1 (CD20), MS4A2 (FcεRIβ), and MS4A3 (HTm4) play an important role in immunity.Citation102 MS4A1 was found to interact with activated B-cell antigen receptor complex to regulate calcium influx. Dysregulation of intracellular calcium signaling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. Recent GWASs have identified three members of MS4A family; MS4A4A, MS4A4E, and MS4A6E associated with LOAD.Citation6,Citation103 To date, many SNPs have been identified in LOAD GWASs, including rs670139 in MS4A4E, rs4938933, and rs1562990 located within the region between MS4A4E and MS4A4A, and rs610932 and rs983392 in MS4A6A.Citation6,Citation103 Aside from rs983392 in MS4A6A, the SNP rs4938933 was also associated with reduced AD risk, while SNPs rs670139 and rs610932 were associated with increased LOAD risk. Recently, Karch et alCitation70 found that MS4A6A expression level and minor allele of rs670139 in MS4A6E were associated with increased Braak tangle and plaque in AD patients. MS4A families affect AD progression and pathogenesis including Aβ generation, tau phosphorylation, and apoptosis by regulating calcium homeostasis. Elevated levels of MS4A4A and MS4A6A may cause detrimental effect on LOAD pathogenesis.

TREM2

TREM2 gene is located on chromosome 6q21.1, which encodes a single-pass type I membrane protein made up of an extracellular immunoglobulin-like domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail, which interacts with DAP12 or TYROBP for its signaling function.Citation104 TREM2 is one of the highly expressed cell surface receptors on microglia that facilitates phagocytosis and downregulation of inflammation. TREM2 is expressed throughout the central nervous system, with highest concentrations in white matter and lowest concentrations in the cerebellum.Citation7 Jonsson et alCitation104 performed whole-genome sequencing in Icelandic population and reported that a missense mutation R47H (rs75932628) within TREM2 was strongly associated with AD with an odds ratio as strong as that for APOE ε4. Similar associations were found in cohorts from the US, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway.Citation104–Citation106 Missense mutation R47H in TREM2 has been reported to increase LOAD risk in a meta-analysis of three imputed data sets of GWASs (EADI, GERAD, and ANM).Citation105 Among six additional variants found by Guerreiro et al,Citation107 three variants (Q33X, Y38C, and T66M) had been related to a frontotemporal dementia-like syndrome without bone involvement in the homozygous state. Recent study by Jin et alCitation106 found 16 rare coding variants in TREM2, of which two variants R47H and R62H were associated with increased LOAD risk. A homozygous mutation in TREM2 was associated with an autosomal recessive form of early-onset dementia called Nasu–Hakola disease.Citation108,Citation109 These patients have multifocal bone cysts predisposing to pathological fracture. Patients with heterozygous loss-of-function mutations have increased risk for LOAD.Citation104,Citation105 TREM2 variant R47H increased risk of neurodegenerative disorders such as frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.Citation107,Citation110,Citation111 TREM2 R47H variant showed accelerated CSF tau and hyperphosphorylated tau protein.Citation112 More extensive brain atrophy was seen in AD patients who carry a TREM2 mutation than noncarriers.Citation113

Genes involved in endocytosis/vesicle-mediated transport

Endocytosis is a critical process in synaptic transmission and response to neural damage. In recent LOAD GWASs, several genes were revealed, which are involved in regulating endocytosis, including BIN1, CD2AP, PICALM, EPHA1, SORL1, etcCitation6,Citation37,Citation38,Citation64,Citation72 (). Most of these genes are involved in APP trafficking, which plays a key role in AD pathogenesis.

BIN1

BIN1 is located on chromosome 2q14.3, and it has more than ten isoforms produced by alternative splicing. BIN1 is implicated in synaptic vesicle endocytosis, intracellular APP trafficking, immune response, apoptosis, and clathrin-mediated endocytosis.Citation114,Citation115 The BIN1 gene locus was initially identified as having a possible association with AD in large GWASs.Citation6,Citation116 Several independent candidate gene studies have replicated and confirmed that SNPs rs744373 and rs7561528 located near BIN1 coding region are associated with LOAD risk. Neuroimaging measures have shown that BIN1 risk variant (SNP rs7561528) was associated with thickening of temporal pole and entorhinal cortex.Citation117 In AD patients, upstream of SNP rs59335482 within the BIN1 was associated with increased tau loads but not with Aβ, suggesting that BIN1 might modulate tau-related AD pathogenesis.Citation118 BIN1 knockdown suppresses tau-mediated neurotoxicity; therefore, BIN1 can act as a therapeutic target for AD. Little is known about the role of BIN1 in neurodegeneration. Therefore, further investigation is required to reveal the role of BIN1 in AD pathogenesis.

CD2AP

CD2AP is an 80 kDa cytoplasmic scaffolding protein located on chromosome 6p12, and it is responsible for regulation of the cytoskeletal structure. CD2AP is also involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis, cell adhesion, intracellular trafficking, cytokinesis, and apoptosis.Citation119 Recently, CD2AP was detected as a risk factor for AD by several GWASs.Citation6,Citation38,Citation72 GWASs of LOAD have identified SNPs rs9296559 and rs9349407 in CD2AP as AD susceptibility loci. CD2AP is expressed in brain and in AD patients. SNP rs9349407 is associated with increased neuritic plaque pathology.Citation120 CD2AP interacts with the presynaptic transmembrane protein called neurexin and thus helps in vesicle trafficking and cell adhesion. A recent APP transgenic mouse model revealed that suppressing CD2AP expression altered Aβ levels and decreased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in vitro. In vivo CD2AP was associated with subtle alteration in the level of Aβ.Citation121 Previous GWASs have failed to show significant association between SNP rs9349407 and CD2AP in Chinese, Japanese, African-American, Canadian, and European populations.Citation6,Citation72 Recently, Chen et alCitation122 reported significant association between CD2AP rs9349407 polymorphism and AD in East Asian, American, Canadian, and European populations.

PICALM

The PICALM gene is situated on chromosome 11q14, and it is ubiquitously expressed with particularly high levels in neurons. Similar to BIN1, PICALM is also implicated in clathrin-mediated endocytosis and intracellular trafficking. The SNPs rs3851179 and rs541458 were found to be associated with LOAD in GWASs for AD risk factors.Citation37,Citation38 PICALM plays a key role in synaptic transmission by the trafficking of VAMP2. In cell culture models and APP/PS1 mice, Xiao et alCitation123 revealed that PICALM facilitates Aβ production by internalizing APP but knockdown of PICALM influenced APP internalization and decreased Aβ production and release. Therefore, PICALM was regarded as a key regulator of brain Aβ production, amyloid plaque load, and APP internalization. SNP rs3851179 in PICALM has been associated with thickening of entorhinal cortex and hippocampal degeneration.Citation117,Citation124 Schjeide et alCitation125 have revealed that the risk allele of PICALM SNP rs541458 was associated with decreased levels of CSF Aβ42 in a dose-dependent manner. Studies have failed to find any associations between PICALM SNPs and tangles, but the PICALM expression was increased in the frontal cortex in AD.Citation126 PICALM plays an important role in Aβ blood–brain barrier transcytosis and clearance.Citation127 PICALM also plays a role in autophagy and tau clearance.Citation128 Treusch et alCitation129 revealed that PICALM modulates Aβ-induced toxicity in a yeast model by impairing endocytosis. Morgen et alCitation130 showed that synergistic interaction of PICALM (rs3851179) and APOE ε4 allele was associated with declined cognitive function and brain atrophy in AD.

EPHA1

EPHA1, located on chromosome 7q34, is a member of the tyrosine kinase family and plays a crucial role in synapse formation and development of the nervous system.Citation131 EPHA1 has high affinity for membrane-bound ligand, ephrins-A1, which regulates bidirectional signaling to adjacent cells via synapse formation.Citation132 EPHA1 is widely expressed in differentiated epithelial cells and lymphocytes. EPHA1 SNPs rs11771145 and rs11767557 were documented to be associated with decreased LOAD risk.Citation6,Citation38,Citation72 Recently, Wang et alCitation133 demonstrated that EPHA1 (rs11771145) genetic variant reduced LOAD risk by functional modification of hippocampus, lateral occipitotemporal, and inferior temporal gyri in AD. EPHA1 is implicated in immune function, synaptic plasticity, chronic inflammation, and cell membrane processes.

Other genes implicated in LOAD

Recent meta-analysis of GWASs identified additional genes implicated in LOAD: HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1, INPP5D, MEF2C, CASS4, PTK2B, NME8, ZCWPW1, CELF1, FERMT2, SLC24H4-RIN3, and DSG2Citation6,Citation37–Citation39 (). Functions of most of these genes are unknown or poorly characterized. These genes may be involved in different possible pathways.Citation134 HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1, INPP5D, and MEF2C are involved in immune response and inflammation. NME8, CELF1, and CASS4 are implicated in cytoskeletal function and axonal transport. PTK2B is involved in hippocampal synaptic function. ZCWPW1 is an epigenetic regulator. FERMT2 is involved in tau pathology and angiogenesis. SLC24H4-RIN3 has possible cardiovascular risk.

HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1

HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1 is situated on chromosome 6p21.3, and it is a member of the major histocompatibility complex class II. HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1 plays an important role in immune response and histocompatibility.Citation135 HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1 is expressed on microglia in the brain. An association of HLA-DRB1 rs9271192 with LOAD was reported in a meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals.Citation38 HLA-DRB1/DRB5 polymorphism was associated with multiple sclerosis.Citation136 Recent GWASs have also shown association between rs3129882 polymorphism in intron 1 of HLA-DRA gene and Parkinson’s disease.Citation137 HLA-DRB5/HLA-DRB1 is also implicated in antigen presentation, inflammation, and complement system.

INPP5D

INPP5D is located on chromosome 2q37.1, and it encodes the SH2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1). INPP5D, also known as SHIP1, is a key regulator of cytokine signaling. The SNP rs35349669, near INPP5D, is associated with increased LOAD risk.Citation38 In addition to the hematopoietic compartment, SHIP is also present in osteoblasts, mature granulocytes, and macrophages. Recently, Chen et alCitation138 found that inhibitor of INPP5D can be used in acute lymphoblastic leukemia to overcome drug resistance. Diseases such as cancer, inflammatory diseases, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and AD may be treated with the help of SHIP modulation.Citation139 SHIP is implicated in multiple signaling pathways, such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, and PI3K is central to signal transduction pathway.

MEF2C

MEF2C is located on 5q14.3, and it encodes a member of the MADS box transcription enhancer factor 2. MEF2C is involved in myogenesis, neurogenesis, and development of multiple organ system. A GWAS in 74,046 individuals revealed that SNP rs190982 near MEF2C is associated with increased LOAD risk.Citation38 MEF2C mutations are associated with severe mental retardation, seizure, cerebral malformation, and stereotypic movements.Citation140 In addition to hematopoietic role, MEF2C regulates B cell proliferation. MEF2C is a regulator of adipose metabolism in vertebrates, and it is a core transcriptional component of the innate immune response of the adult fly.Citation141

CASS4

CASS4 is located on chromosome 20q13.31, and it is also known as HEPL. CASS4 is widely expressed in the lung and spleen, and CASS4 mRNA expression is highest in leukemia cell lines.Citation142 Although the exact function of CASS4 is unknown, it appears to play an important role in focal adhesion kinase regulation, cellular adhesion, cell migration, and motility.Citation142 In a meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals, CASS4 SNP rs7274581 has been associated with decreased LOAD risk.Citation38 Recently, CASS4 was associated with neuritic plaques burden and neurofibrillary tangles in brains with AD.Citation143 The SNPs rs6024870 and rs16979934 near CASS4 were identified as AD risk alleles in GWASs in LOAD.Citation134,Citation144 CASS4 plays a vital role in inflammation, calcium signaling, and microtubule stabilization, suggesting that CASS4 might be associated with AD pathogenesis.Citation145

PTK2B

PTK2B (also known as PYK2, Cak2β, or RAFTK) is located on chromosome 8p21.1, and it encodes a cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinase, which is involved in calcium-induced regulation of ion channels and activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathway.Citation146 PTK2B is highly expressed in the central nervous system. SNP in PTK2B (rs28834970) was associated with LOAD risk in 74046 individuals from diverse ethnicities.Citation38 SNP–SNP interaction between rs28834970–rs6656401 (PTK2B-CR1) and rs28834970–rs6656401 (PTK2B-CD33) was associated with increased LOAD risk.Citation147 Recently, Kaufman et al demonstrated that downstream signaling from Fyn to the AD risk gene product, Pyk2, was blocked by Fyn kinase inhibitor, AZD0530, in Alzheimer mice. Fyn kinase inhibitions improved the learning and memory impairment in Alzheimer mice.Citation148 There is a strong interaction between calcium homeostasis and NEDD9 and PTK2B.Citation145 Hence, PTK2B might be of immense value to investigate its functional role in the context of AD.

NME8

NME8 is located on chromosome 7p14.1, and it encodes a protein with an N-terminal thioredoxin domain and C-terminal nucleoside diphosphate kinase domains. NME8 is member of NM23 family, and it is involved in proliferation and differentiation of neuronal cells.Citation149 SNP (rs2718058) adjacent to NME8 was associated with decreased LOAD risk.Citation38 Liu et alCitation150 found that there is positive correlation between NME8 (rs2718058) genetic variants and AD pathological features such as cognitive decline, the elevated tau levels in CSF, and the hippocampus atrophy. NME8 has also been associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia and knee osteoarthritis.Citation151,Citation152

ZCWPW1

Zinc finger CW (zf-CW) domain consists of 60 amino acids. Although the function of zf-CW domain is unknown, it might be regarded as a new histone modification reader. zf-CW domain is found in methylation or demethylation enzymes and several other proteins.Citation153 ZCWPW1 is located on chromosome 7q22.1, and it may be involved in epigenetic regulation by histone modification.Citation153 Rosenthal et alCitation144 reported genome-wide significant SNPs (ZCWPW1/rs1476679) associated with LOAD. Protective LOAD allele SNP rs1476679 at ZCWPW1 affects binding of CTCF and RFX3 in K562 by acting expression quantitative trait loci for GATS, PILRB, and TRIM4.Citation143 Recently, ZCWPW1/PILRB locus mapping showed that SNP rs1476679 was associated with decreased level of PILRB and LOAD risk in one group, while in another group with increased levels of PILRB and no association with LOAD.Citation154

CELF1

CELF1, located on chromosome on 11p11, is a member of the CELF/BRUNOL protein family that is implicated in the regulation of pre-mRNA alternative splicing, mRNA editing, and mRNA translation.Citation155 The SNP rs10838725 located in an intron of the CELF1 gene was associated with LOAD risk.Citation144 Recent studies have shown that CELF1 is overexpressed in many human malignant tumors, and it is also upregulated in glioma and promotes glioma cell proliferation.Citation156,Citation157 The role of CELF1 in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), cytoskeletal function, and axonal transport was also reported.Citation158 LOAD susceptible gene CELF1 mediates tau toxicity in drosophila.Citation159

FERMT2

FERMT2 (also known as kindlin-2, KIND2) is located on chromosome 14q22.1, and it regulates integrin activation by binding to the integrin β cytoplasmic tail via a C-terminal domain.Citation160 Kindlin-2 was involved in the progression of non-small-cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and gastric cancer.Citation161–Citation163 Kindlin-2 is also essential for myogenesis and angiogenesis.Citation164,Citation165 The SNP rs17125944 located in FERMT2 gene was associated with LOAD risk.Citation134 Study in flies showed that tau toxicity is modulated by altered expression of CELF1 and FERMT2, suggesting a potential role of FERMT2 in AD pathogenesis.Citation159

SLC24A4/RIN3

SLC24A4 (also known as NCKX4) is located on chromosome 14q32.12, and it encodes a member of the potassium-dependent sodium/calcium exchanger. SLC24A4 is associated with neural development, hair color, and skin pigmentation.Citation166,Citation167 SNP rs10498633 located at intron of SLC24A4 is associated with LOAD risk.Citation134 Yu et alCitation168 found the association of SLC24A4 with methylation, and brain DNA methylation has a role in the pathology of AD. RIN3 is located near SNP rs10498633 of SLC24A4. Interaction of RIN3 and BIN1 plays an important role in endocytic pathway.Citation169 SLC24A4 is also involved in lipid metabolism.Citation170

DSG2

DSG2 is located on chromosome 18q12.1, and it encodes calcium binding transmembrane glycoprotein desmoglein. Desmoglein-2 expression is abundant in epithelial cells and cardiomyocytes. SNP rs8093731 at DSG2 reached genome-wide significance for LOAD in stage 1 but was not replicated in stage 2.Citation38 Mutations in DSG2 have been associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and sudden unexplained death.Citation171 Alterations in the expression of desmogleins have been reported for a variety of cancers. There is reduced expression of DSG2 in pancreatic cancer and overexpression of DSG2 in squamous cell carcinomas of the skin.Citation172,Citation173

Novel sequencing technologies and rare variants

GWASs successfully identified many common variants with low penetrance, not the rare variants associated with LOAD. However, advances in sequencing techniques such as whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome sequencing have proven to be very powerful techniques to identify novel genes with low-frequency variants associated with both EOAD and LOAD. Using novel sequencing technologies, the following genes have been identified: TREM2, PLD3, UNC5C, AKAP9, and ADAM10Citation104,Citation107,Citation174 ().

PLD3

PLD3 is located at chromosome 19q13.2, and it encodes a nonclassical PLD3 protein associated with the endoplasmic reticulum. PLD3 is highly expressed in brain (such as frontal, temporal, and occipital cortices and hippocampus), and it may be involved in neurotransmission, cell differentiation, epigenetic modifications, and signal transduction.Citation175 Whole-exome sequencing performed by Cruchaga et alCitation175 found that the rare missense variant V232M (rs145999145) in exon 7 of PLD3 was associated with increased risk of LOAD. PLD1 and PLD2 have been associated with Aβ pathology; little is known about the actions of PLD3 in AD. Cruchaga et alCitation175 revealed that PLD3 may be involved in APP processing and is overexpressed in brain tissue from AD patients.Citation174 Satoh et alCitation176 found that accelerated accumulation of PLD3 on neuritic plaques in AD brains may be associated with AD pathology. Compared with control brains, PLD3 is expressed at lower level in neurons from AD brains. Decreased expression of PLD3 is associated with increase in extracellular Aβ42 and Aβ40.Citation174

UNC5C

UNC5C gene is located on chromosome 4q22.3, and it is highly expressed in the adult hippocampus and cerebellum neurons. Whole-genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing in European ancestry revealed the rare coding variant T835M (rs137875858) in netrin receptor UNC5C gene that showed significant association with LOAD.Citation177 A study by Wetzel-Smith et alCitation177 revealed that neurons with overexpression of T835M UNC5C are more prone to Aβ-mediated cell death, and T835M carriers with enhanced expression of UNC5C in the hippocampus are at increased risk of AD. In Chinese Han population, four rare variants were detected near rs137875858, of which rs137875858 variant showed association with AD.Citation178 Hunkapiller et alCitation179 showed that protein structure and death domain are affected by overexpression of UNC5C variant T835M, and T835M carriers are more vulnerable to LOAD.

APP rare variant A673T

Jonsson et alCitation25 performed whole-genome sequencing in Icelandic population, and they found that a rare APP A673T substitution (rs63750847) confers protection against LOAD. This variant was found to be more common in healthy elderly controls than in AD and was associated with decreased cognitive decline among elderly subjects without a diagnosis of AD, suggesting the protective role of rare APP A673T variant in LOAD.Citation25 A673T variant reduces BACE1 cleavage of APP in primary neurons, resulting in decreased production and aggregation of Aβ in A673T carrier.Citation180 In contrast to other Nordic populations, the A673T variant appears to be extremely rare in Danish and Asian population.Citation181,Citation182

AKAP9

AKAP9 is located on chromosome 7q21-q22, and it encodes a member of the AKAP family. AKAP9 is alternatively spliced into many isoforms that localize to cellular compartments such as centrosome and the Golgi apparatus. Logue et alCitation183 conducted whole-exome sequencing in African American cases and identified two rare variants (rs144662445 and rs149979685 within AKAP9) associated with AD. AKAP9 is expressed in the hippocampus, cerebellum, and the cerebral cortex and interacts with numerous signaling proteins from multiple signal transduction pathways. Recently, Venkatesh et alCitation184 found that deletion of AKAP9 in mice resulted in marked alterations in the organization of microtubules affecting blood–testis barrier function and subsequent germ cell development during spermatogenesis. Mutation in AKAP9 was also associated with long QT syndrome-11 and congenital long QT syndrome type 1 might be genetically modified by AKAP9.Citation185

ADAM10

ADAM10 is located on chromosome 15q22, and it is ubiquitously expressed in a wide range of cell types, such as the neuroblastoma, kidney cell line, and the hepatocytes. Kim et alCitation186 conducted genotyping and targeted sequencing in 995 cases and 411 controls of European American origin and revealed that rare variant rs2305421 was associated with AD. However, Cai et alCitation187 found that rare coding variation in ADAM10 was not associated with sporadic AD. Suh et alCitation188 found two rare mutations (Q170H and R181G) related to LOAD in ADAM10 and demonstrated that ADAM10 mutations increased plaque load and Aβ levels and affect hippocampal neurogenesis in Tg2576 AD mice.

Challenges, controversies, and future insights

Despite years of research, much of the heritability of AD remains unexplained. Currently, most of the known genes are unable to explain a large proportion of the heritability for LOAD. Linkage studies have not been effective in elucidating the genetic basis of LOAD due to small sample size and vulnerability to locus heterogeneity. Candidate gene studies have not been successful in replicating genes consistently due to small sample size, locus heterogeneity, and false-positive results. Due to poor understanding of roles of encoded proteins, underlying biology, and effects of risk variants in AD pathogenesis, no therapeutic interventions have been developed to treat AD. Although mouse knockout models have be used to study normal biology and the pathology of AD, the AD field as a whole has struggled to develop drugs and potential novel targets from mouse models into effective therapies.

Recent studies have raised questions regarding the validity of the amyloid hypothesis that has driven drug development strategies for AD for >20 years but has not been unequivocally disproven, despite multiple clinical failures.Citation189,Citation190 They concluded that the amyloid hypothesis may be failing therapeutically and suggest we expand our view of pathogenesis beyond Aβ and tau pathology for the understanding of AD pathogenesis.

Experience from other complex diseases suggests that genes emerging from several studies require further validation via genetic replication and through functional assessment by in vitro and in vivo approaches to uncover common genetic factors for AD. NGS can be used to detect rare and structural variations in candidate regions. Novel approach can be developed to reassess the GWAS. Use of endophenotype including cerebral spinal fluid biomarker data, quantitative neuropathology measures, and phenotypes may be powerful tools for the identification of genetic factors that influence AD risk and plausible biological pathways. Future research should be focused on identifying low effect size and rare variants that may explain missing heritability. In future, deep resequencing can be used for an effective and accurate approach to identify novel rare variants associated with AD, which might provide further insights into the underlying mechanisms of disease. It is evident that epistatic interaction is involved in complex diseases such as AD, and this should not be ignored. Furthermore, novel risk genes for AD can be identified by gene profiling. Additionally, missing AD heritability can be addressed with the development of more sophisticated statistical analyses.

Conclusion

AD is a complex neurodegenerative disease with a strong genetic component. AD is a major public health problem, and currently, there is no treatment to slow down the progression of AD. With the advance of molecular genetics, many studies are widely performed in search of the genes responsible for both autosomal dominant forms of AD and sporadic AD. Linkage studies revealed APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and APOE as AD genes. GWASs have identified >20 loci associated with AD risk. The majority of genes associated with AD roughly cluster within three pathways: lipid metabolism, inflammatory response, and endocytosis. Sequencing technologies have enabled the identification of rare disease variants, such as PLD3, TREM2, UNC5C, AKAP9, and ADAM10. Future studies will likely use more sophisticated methods of GWAS and whole-genome sequencing to reveal more risk loci for AD. Hence, a better understanding of genetic complexity of AD and the elucidation of possible molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in AD are the cornerstone for the development of effective prevention and treatment strategies for AD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from National Key Clinical Specialties Construction Program of China (no [2013]544), Application Program of Chongqing Science & Technology Commission (cstc2014yykfA110002), Sub-project under Science and Technology Program for Public Well-being of Chongqing Science & Technology Commission (cstc2015jcsf10001-01-01), and Sub-project of National Science and Technology Supporting Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2015BAI06B04).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease International Consortium [webpage on the Internet]World Alzheimer Report 2015 Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdfAccessed April 11, 2016

- BlennowKde LeonMJZetterbergHAlzheimer’s diseaseLancet2006368953338740316876668

- GatzMReynoldsCAFratiglioniLRole of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer diseaseArch Gen Psychiatry200663216817416461860

- BuGApolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapyNat Rev Neurosci200910533334419339974

- HuangYMuckeLAlzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategiesCell201214861204122222424230

- NajACJunGBeechamGWCommon variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet201143543644121460841

- SeshadriSFitzpatrickALIkramMAGenome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer diseaseJAMA2010303181832184020460622

- BertramLNext generation sequencing in Alzheimer’s diseaseMethods Mol Biol2016130328129726235074

- TanziREBertramLTwenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspectiveCell2005120454555515734686

- VerghesePBCastellanoJMHoltzmanDMApolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disordersLancet Neurol201110324125221349439

- HattersleyATMcCarthyMIA question of standards: what makes a good genetic association study?Lancet200536694931315132316214603

- KarchCMCruchagCGoateAMAlzheimer’s disease genetics: from the bench to the clinicNeuron2014831112624991952

- CrutsMTheunsJVan BroeckhovenCLocus-specific mutation databases for neurodegenerative brain diseasesHum Mutat20123391340134422581678

- YoshikaiSSasakiHDoh-uraKFuruyaHSakakiYGenomic organization of the human amyloid beta-protein precursor geneGene19908722572632110105

- ThinakaranGKooEHAmyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing and functionJ Biol Chem200828344296152961918650430

- BekrisLMYuCEBirdTDTsuangDWGenetics of Alzheimer diseaseJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol201023421322721045163

- GuerreiroRJGustafsonDRHardyJThe genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease: beyond APP, PSENs and APOENeurobiol Aging201233343745620594621

- De JongheCEsselensCKumar-SinghSPathogenic APP mutations near the gamma-secretase cleavage site differentially affect Abeta secretion and APP C-terminal fragment stabilityHum Mol Genet200110161665167111487570

- MullanMCrawfordFAxelmanKA pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer’s disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of β-amyloidNat Genet1992153453471302033

- PrasherVPFarrerMJKesslingAMMolecular mapping of Alzheimer-type dementia in Down’s syndromeAnn Neurol19984333803839506555

- GoateAChartier-HarlinMCMullanMSegregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s diseaseNature199134963117047061671712

- NilsberthCWestlind-DanielssonAEckmanCBThe ‘Arctic’ APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer’s disease by enhanced Abeta protofibril formationNat Neurosci20014988789311528419

- KaminoKOrrHTPayamiHLinkage and mutational analysis of familial Alzheimer disease kindreds for the APP gene regionAm J Hum Genet199251599810141415269

- HendriksLvan DuijnCMCrasPPresenile dementia and cerebral haemorrhage linked to a mutation at codon 692 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein geneNat Genet1992132182211303239

- JonssonTAtwalJKSteinbergSA mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive declineNature20124887409969922801501

- EslerWPWolfeMSA portrait of Alzheimer secretases – new features and familiar facesScience200129355341449145411520976

- SteinerHUncovering gamma-secretaseCurr Alzheimer Res20041317518115975065

- SteinerHReveszTNeumannMA pathogenic presenilin-1 deletion causes aberrant Abeta 42 production in the absence of congophilic amyloid plaquesJ Biol Chem2001276107233723911084029

- TakaoMGhettiBHayakawaIA novel mutation (G217D) in the Presenilin 1 gene (PSEN1) in a Japanese family: presenile dementia and parkinsonism are associated with cotton wool plaques in the cortex and striatumActa Neuropathol2002104215517012111359

- VerkkoniemiAKalimoHPaetauAVariant Alzheimer disease with spastic paraparesis: neuropathological phenotypeJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol200160548349211379823

- BreyhanHWirthsODuanKMarcelloARettigJBayerTAAPP/PS1KI bigenic mice develop early synaptic deficits and hippocampus atrophyActa Neuropathol2009117667768519387667

- PiginoGMorfiniGPelsmanAMattsonMPBradySTBusciglioJAlzheimer’s presenilin 1 mutations impair kinesin-based axonal transportJ Neurosci200323114499450812805290

- WakabayashiTDe StrooperBPresenilins: members of the gamma-secretase quartets, but part-time soloists tooPhysiology (Bethesda)200823419420418697993

- JayadevSLeverenzJBSteinbartEAlzheimer’s disease phenotypes and genotypes associated with mutations in presenilin 2Brain201013341143115420375137

- ParkMHChoiDYJinHWMutant presenilin 2 increases β-secretase activity through reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinaseJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol201271213013922249458

- BentahirMNyabiOVerhammeJPresenilin clinical mutations can affect gamma-secretase activity by different mechanismsJ Neurochem200696373274216405513

- HaroldDAbrahamRHollingworthPGenome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet200941101088109319734902

- LambertJCIbrahim-VerbaasCAHaroldDEuropean Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative (EADI)Genetic and Environmental Risk in Alzheimer’s DiseaseAlzheimer’s Disease Genetic ConsortiumCohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic EpidemiologyMeta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet201345121452145824162737

- BertramLLangeCMullinKGenome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOEAm J Hum Genet200883562363218976728

- SolomonAKivipeltoMWolozinBZhouJWhitmerRAMidlife serum cholesterol and increased risk of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia three decades laterDement Geriatr Cogn Disord2009281758019648749

- CorderEHSaundersAMStrittmatterWJGene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset familiesScience199326151239219238346443

- SaundersAMStrittmatterWJSchmechelDAssociation of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s diseaseNeurology1993438146714728350998

- SaundersAMApolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: an update on genetic and functional analysesJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol200059975175811005255

- RosesADApolipoprotein E alleles as risk factors in Alzheimer’s diseaseAnnu Rev Med1996473874008712790

- MahleyRWWeisgraberKHHuangYApolipoprotein E: structure determines function, from atherosclerosis to Alzheimer’s disease to AIDSJ Lipid Res200950supplS183S18819106071

- HerzJChenYMasiulisIZhouLExpanding functions of lipoprotein receptorsJ Lipid Res200950supplS287S29219017612

- GajeraCREmichHLioubinskiOLRP2 in ependymal cells regulates BMP signaling in the adult neurogenic nicheJ Cell Sci2010123111922193020460439

- PastorPRoeCMVillegasAApolipoprotein Eepsilon4 modifies Alzheimer’s disease onset in an E280A PS1 kindredAnn Neurol200354216316912891668

- VélezJILoperaFSepulveda-FallaDAPOE*E2 allele delays age of onset in PSEN1 E280A Alzheimer’s diseaseMol Psychiatry Epub2015121

- CastellanoJMKimJStewartFRHuman apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearanceSci Transl Med201138989ra57

- KimJBasakJMHoltzmanDMThe role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s diseaseNeuron200963328730319679070

- BalesKRLiuFWuSHuman APOE isoform-dependent effects on brain β-amyloid levels in PDAPP transgenic miceJ Neurosci200929216771677919474305

- KokEHaikonenSLuotoTApolipoprotein E–dependent accumulation of Alzheimer disease–related lesions begins in middle ageAnn Neurol200965665065719557866

- PolvikoskiTSulkavaRHaltiaMApolipoprotein E, dementia, and cortical deposition of beta-amyloid proteinN Engl J Med199533319124212477566000

- DoreyEChangNLiuQYYangZZhangWApolipoprotein E, amyloid-beta, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s diseaseNeurosci Bull201430231733024652457

- HanMRSchellenbergGDWangLSAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeGenome-wide association reveals genetic effects on human Aβ42 and τ protein levels in cerebrospinal fluids: a case control studyBMC Neurol2010109020932310

- ChiangGCInselPSTosunDAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeHippocampal atrophy rates and CSF biomarkers in elderly APOE2 normal subjectsNeurology201075221976198120980669

- LaDuMJFaldutoMTManelliAMReardonCAGetzGSFrailDEIsoform-specific binding of apolipoprotein E to beta-amyloidJ Biol Chem19942693823403234068089103

- PoirierJApolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease. A role in amyloid catabolismAnn N Y Acad Sci2000924819011193807

- LuPHThompsonPMLeowAApolipoprotein E genotype is associated with temporal and hippocampal atrophy rates in healthy elderly adults: a tensor-based morphometry studyJ Alzheimers Dis201123343344221098974

- PotkinSGGuffantiGLakatosAAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeHippocampal atrophy as a quantitative trait in a genome-wide association study identifying novel susceptibility genes for Alzheimer’s diseasePLoS One200948e650119668339

- RamananVKRisacherSLNhoKAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeAPOE and BCHE as modulators of cerebral amyloid deposition: a florbetapir PET genome-wide association studyMol Psychiatry201419335135723419831

- YatesPADesmondPMPhalPMAIBL Research GroupIncidence of cerebral microbleeds in preclinical Alzheimer diseaseNeurology201482141266127324623839

- LambertJCHeathSEvenGGenome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet200941101094109919734903

- NuutinenTSuuronenTKauppinenASalminenAClusterin: a forgotten player in Alzheimer’s diseaseBrain Res Rev20096128910419651157

- JonesSEJomaryCClusterinInt J Biochem Cell Biol200234542743111906815

- RosenbergMESilkensenJClusterin: physiologic and pathophysiologic considerationsInt J Biochem Cell Biol19952776336457648419

- LidströmAMBogdanovicNHesseCVolkmanIDavidssonPBlennowKClusterin (apolipoprotein J) protein levels are increased in hippocampus and in frontal cortex in Alzheimer’s diseaseExp Neurol199815425115219878186

- SchrijversEMKoudstaalPJHofmanABretelerMMPlasma clusterin and the risk of Alzheimer diseaseJAMA2011305131322132621467285

- KarchCMJengATNowotnyPCadyJCruchagaCGoateAMExpression of novel Alzheimer’s disease risk genes in control and Alzheimer’s disease brainsPLoS One2012711e5097623226438

- DemingYXiaJCaiYAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)A potential endophenotype for Alzheimer’s disease: cerebrospinal fluid clusterinNeurobiol Aging201637208.e1208.e926545630

- HollingworthPHaroldDSimsRCommon variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet201143542943521460840

- KimWSGuilleminGJGlarosENLimCKGarnerBQuantitation of ATP-binding cassette subfamily-A transporter gene expression in primary human brain cellsNeuroreport200617989189616738483

- HoltonPRytenMNallsMInitial assessment of the pathogenic mechanisms of the recently identified Alzheimer risk LociAnn Hum Genet20137728510523360175

- ReitzCJunGNajAAlzheimer Disease Genetics ConsortiumVariants in the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA7), apolipoprotein E∈4, and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease in African AmericansJAMA2013309141483149223571587

- KimWSLiHRuberuKDeletion of Abca7 increases cerebral amyloid-β accumulation in the J20 mouse model of Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Neurosci201333104387439423467355

- ChanSLKimWSKwokJBATP-binding cassette transporter A7 regulates processing of amyloid precursor protein in vitroJ Neurochem2008106279380418429932

- SteinbergSStefanssonHJonssonTLoss-of-function variants in ABCA7 confer risk of Alzheimer’s diseaseNat Genet201547544544725807283

- AndersenOMReicheJSchmidtVNeuronal sorting protein-related receptor sorLA/LR11 regulates processing of the amyloid precursor proteinProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200510238134611346616174740

- FjorbackAWSeamanMGustafsenCRetromer binds the FANSHY sorting motif in SorLA to regulate amyloid precursor protein sorting and processingJ Neurosci20123241467148022279231

- GustafsenCGlerupSPallesenLTSortilin and SorLA display distinct roles in processing and trafficking of amyloid precursor proteinJ Neurosci2013331647123283322

- RogaevaEMengYLeeJHThe neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer diseaseNat Genet200739216817717220890

- TsolakidouAAlexopoulosPGuoLHBeta-Site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 activity is related to cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of sortilin-related receptor with A-type repeats, soluble amyloid precursor protein, and tauAlzheimers Dement20139438639123127467

- OffeKDodsonSEShoemakerJTThe lipoprotein receptor LR11 regulates amyloid beta production and amyloid precursor protein traffic in endosomal compartmentsJ Neurosci20062651596160316452683

- CapsoniSCarloASVignoneDSorLA deficiency dissects amyloid pathology from tau and cholinergic neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Alzheimers Dis201333235737122986780

- LeeJHBarralSReitzCThe neuronal sortilin-related receptor gene SORL1 and late-onset Alzheimer’s diseaseCurr Neurol Neurosci Rep20088538439118713574

- ReitzCChengRRogaevaEGenetic and Environmental Risk in Alzheimer Disease 1 ConsortiumMeta-analysis of the association between variants in SORL1 and Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol20116819910621220680

- CuencoKTLunettaKLBaldwinCTAssociation of distinct variants in SORL1 with cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative changes related to Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol200865121640164819064752

- De StrooperBAnnaertWProteolytic processing and cell biological functions of the amyloid precursor proteinJ Cell Sci2000113pt 111857187010806097

- WangZLeiHZhengMLiYCuiYHaoFMeta-analysis of the Association between Alzheimer Disease and Variants in GAB2, PICALM, and SORL1Mol Neurobiol Epub20151127

- WilsonJGAndriopoulosNAFearonDTCR1 and the cell membrane proteins that bind C3 and C4. A basic and clinical reviewImmunol Res1987631922092960763

- KheraRDasNComplement Receptor 1: disease associations and therapeutic implicationsMol Immunol200946576177219004497

- BonifatiDMKishoreURole of complement in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammationMol Immunol2007445999101016698083

- KokEHLuotoTHaikonenSGoebelerSHaapasaloHKarhunenPJCLU, CR1 and PICALM genes associate with Alzheimer’s-related senile plaquesAlzheimers Res Ther2011321221466683

- BraltenJFrankeBArias-VasquezACR1 genotype is associated with entorhinal cortex volume in young healthy adultsNeurobiol Aging201132112106.e72106.e1121726919

- BrouwersNVan CauwenbergheCEngelborghsSAlzheimer risk associated with a copy number variation in the complement receptor 1 increasing C3b/C4b binding sitesMol Psychiatry201217222323321403675

- BiffiAShulmanJMJagiellaJMGenetic variation at CR1 increases risk of cerebral amyloid angiopathyNeurology201278533434122262751

- JandusCSimonHUvon GuntenSTargeting Siglecs – a novel pharmacological strategy for immuno- and glycotherapyBiochem Pharmacol201182432333221658374

- TatenoHLiHSchurMJDistinct endocytic mechanisms of CD22 (Siglec-2) and Siglec-F reflect roles in cell signaling and innate immunityMol Cell Biol200727165699571017562860

- GriciucASerrano-PozoAParradoARAlzheimer’s disease risk gene CD33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid betaNeuron201378463164323623698

- BradshawEMChibnikLBKeenanBTCD33 Alzheimer’s disease locus: altered monocyte function and amyloid biologyNat Neurosci201316784885023708142

- ZuccoloJDengLUnruhTLExpression of MS4A and TMEM176 genes in human B lymphocytesFront Immunol2013419523874341

- AntunezCBoadaMGonzalez-PerezAAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeThe membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A (MS4A) gene cluster contains a common variant associated with Alzheimer’s diseaseGenome Med2011353321627779

- JonssonTStefanssonHSteinbergSVariant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med2013368210711623150908

- GuerreiroRWojtasABrasJAlzheimer Genetic Analysis GroupTREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med2013368211712723150934

- JinSCBenitezBAKarchCMCoding variants in TREM2 increase risk for Alzheimer’s diseaseHum Mol Genet201423215838584624899047

- GuerreiroRJLohmannEBrásJMUsing exome sequencing to reveal mutations in TREM2 presenting as a frontotemporal dementia-like syndrome without bone involvementJAMA Neurol2013701788423318515

- PalonevaJKestiläMWuJLoss-of-function mutations in TYROBP (DAP12) result in a presenile dementia with bone cystsNat Genet200025335736110888890

- PalonevaJManninenTChristmanGMutations in two genes encoding different subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical disease phenotypeAm J Hum Genet200271365666212080485

- RayaproluSMullenBBakerMTREM2 in neurodegeneration: evidence for association of the p.R47H variant with frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s diseaseMol Neurodegener201381923800361

- CadyJKovalEDBenitezBATREM2 variant p.R47H as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosisJAMA Neurol201471444945324535663

- CruchagaCKauweJSHarariOGERAD ConsortiumAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)Alzheimer Disease Genetic Consortium (ADGC)GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s diseaseNeuron201378225626823562540

- RajagopalanPHibarDPThompsonPMTREM2 and neurodegenerative diseaseN Engl J Med2013369161565156724131186

- PantSSharmaMPatelKCaplanSCarrCMGrantBDAMPH-1/Amphiphysin/Bin1 functions with RME-1/Ehd1 in endocytic recyclingNat Cell Biol200911121399141019915558

- TanMSYuJTTanLBridging integrator 1 (BIN1): form, function, and Alzheimer’s diseaseTrends Mol Med2013191059460323871436

- KambohMIDemirciFYWangXGenome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s diseaseTransl Psychiatry20122e11722832961

- BiffiAAndersonCDDesikanRSGenetic variation and neuroimaging measures in Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol201067667768520558387

- ChapuisJHansmannelFGistelinckMIncreased expression of BIN1 mediates Alzheimer genetic risk by modulating tau pathologyMol Psychiatry201318111225123423399914

- MonzoPGauthierNCKeslairFClues to CD2-associated protein involvement in cytokinesisMol Biol Cell20051662891290215800069

- ShulmanJMChenKKeenanBTGenetic susceptibility for Alzheimer disease neuritic plaque pathologyJAMA Neurol20137091150115723836404

- LiaoFJiangHSrivatsanSEffects of CD2-associated protein deficiency on amyloid-β in neuroblastoma cells and in an APP transgenic mouse modelMol Neurodegener2015101225887956

- ChenHWuGJiangYAnalyzing 54,936 samples supports the association between CD2AP rs9349407 polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease susceptibilityMol Neurobiol20155211725092125

- XiaoQGilSCYanPRole of phosphatidylinositol clathrin assembly lymphoid-myeloid leukemia (PICALM) in intracellular amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and amyloid plaque pathogenesisJ Biol Chem201228725212792128922539346

- MelvilleSABurosJParradoARAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeMultiple loci influencing hippocampal degeneration identified by genome scanAnn Neurol2012721657522745009

- SchjeideBMSchnackCLambertJCThe role of clusterin, complement receptor 1, and phosphatidylinositol binding clathrin assembly protein in Alzheimer disease risk and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker levelsArch Gen Psychiatry201168220721321300948

- BaigSJosephSATaylerHDistribution and expression of picalm in Alzheimer diseaseJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol201069101071107720838239

- ZhaoZSagareAPMaQCentral role for PICALM in amyloid-β blood-brain barrier transcytosis and clearanceNat Neurosci201518797898726005850

- MoreauKFlemingAImarisioSPICALM modulates autophagy activity and tau accumulationNat Commun20145499825241929

- TreuschSHamamichiSGoodmanJLFunctional links between Abeta toxicity, endocytic trafficking, and Alzheimer’s disease risk factors in yeastScience201133460601241124522033521

- MorgenKRamirezAFrölichLGenetic interaction of PICALM and APOE is associated with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement2014105 supplS269S27624613704

- LaiKOIpNYSynapse development and plasticity: roles of ephrin/Eph receptor signalingCurr Opin Neurobiol200919327528319497733

- YamazakiTMasudaJOmoriTUsuiRAkiyamaHMaruYEphA1 interacts with integrin-linked kinase and regulates cell morphology and motilityJ Cell Sci2009122pt 224325519118217

- WangHFTanLHaoXKEffect of EPHA1 genetic variation on cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers in healthy, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease cohortsJ Alzheimers Dis201544111512325182741

- RuizAHeilmannSBeckerTFollow-up of loci from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease Project identifies TRIP4 as a novel susceptibility geneTransl Psychiatry20144e35824495969

- GuerreiroRBrásJHardyJSnapShot: genetics of Alzheimer’s diseaseCell20131554968968.e124209629

- LangHLJacobsenHIkemizuSA functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosisNat Immunol200231094094312244309

- HamzaTHZabetianCPTenesaACommon genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson’s diseaseNat Genet201042978178520711177

- ChenZShojaeeSBuchnerMSignalling thresholds and negative B-cell selection in acute lymphoblastic leukaemiaNature2015521755235736125799995

- ViernesDRChoiLBKerrWGChisholmJDDiscovery and development of small molecule SHIP phosphatase modulatorsMed Res Rev201434479582424302498

- NowakowskaBAObersztynESzymanskaKSevere mental retardation, seizures, and hypotonia due to deletions of MEF2CAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2010153b51042105120333642

- ClarkRITanSWPéanCBMEF2 is an in vivo immune-metabolic switchCell2013155243544724075010

- SinghMKDadkeDNicolasEA novel Cas family member, HEPL, regulates FAK and cell spreadingMol Biol Cell20081941627163618256281

- BeechamGWHamiltonKNajACGenome-wide association meta-analysis of neuropathologic features of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementiasPLoS Genet2014109e100460625188341

- RosenthalSLBarmadaMMWangXDemirciFYKambohMIConnecting the dots: potential of data integration to identify regulatory SNPs in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease GWAS findingsPLoS One201494e9515224743338

- BeckTNNicolasEKoppMCGolemisEAAdaptors for disorders of the brain? The cancer signaling proteins NEDD9, CASS4, and PTK2B in Alzheimer’s diseaseOncoscience20141748650325594051

- AlierKAMorrisBJDivergent regulation of Pyk2/CAKbeta phosphorylation by Ca2+ and cAMP in the hippocampusBiochim Biophys Acta20051745334234916120467

- JiaoBLiuXZhouLPolygenic analysis of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease from mainland ChinaPLoS One20151012e014489826680604

- KaufmanACSalazarSVHaasLTFyn inhibition rescues established memory and synapse loss in Alzheimer miceAnn Neurol201577695397125707991

- KimSHFountoulakisMCairnsNJLubecGHuman brain nucleoside diphosphate kinase activity is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndromeBiochem Biophys Res Commun2002296497097512200143

- LiuYYuJTWangHFAssociation between NME8 locus polymorphism and cognitive decline, cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers in Alzheimer’s diseasePLoS One2014912e11477725486118

- DuriezBDuquesnoyPEscudierEA common variant in combination with a nonsense mutation in a member of the thioredoxin family causes primary ciliary dyskinesiaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A20071043336334117360648

- ShiDNakamuraTNakajimaMAssociation of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in RHOB and TXNDC3 with knee osteoarthritis susceptibility: two case-control studies in East Asian populations and a meta-analysisArthritis Res Ther2008103R5418471322

- HeFUmeharaTSaitoKStructural insight into the zinc finger CW domain as a histone modification readerStructure20101891127113920826339

- AllenMKachadoorianMCarrasquilloMMLate-onset Alzheimer disease risk variants mark brain regulatory lociNeurol Genet201512e1527066552

- BeisangDReillyCBohjanenPRAlternative polyadenylation regulates CELF1/CUGBP1 target transcripts following T cell activationGene201455019310025123787

- HouseRPTalwarSHazardESHillEGPalanisamyVRNA-binding protein CELF1 promotes tumor growth and alters gene expression in oral squamous cell carcinomaOncotarget2015641436204363426498364

- XiaLSunCLiQCELF1 is up-regulated in glioma and promotes glioma cell proliferation by suppression of CDKN1BInt J Biol Sci201511111314132426535026

- Kuyumcu-MartinezNMWangGSCooperTAIncreased steady-state levels of CUGBP1 in myotonic dystrophy 1 are due to PKC-mediated hyperphosphorylationMol Cell2007281687817936705

- ShulmanJMImboywaSGiagtzoglouNFunctional screening in Drosophila identifies Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility genes and implicates Tau-mediated mechanismsHum Mol Genet201423487087724067533

- KahnerBNKatoHBannoAGinsbergMHShattilSJYeFKindlins, integrin activation and the regulation of talin recruitment to αIIbβ3PLoS One201273e3405622457811

- ZhanJZhuXGuoYOpposite role of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 in lung cancersPLoS One2012711e5031323209705

- YuYWuJGuanLKindlin 2 promotes breast cancer invasion via epigenetic silencing of the microRNA200 gene familyInt J Cancer201313361368137923483548

- ShenZYeYKauttuTNovel focal adhesion protein kindlin-2 promotes the invasion of gastric cancer cells through phosphorylation of integrin beta1 and beta3J Surg Oncol2013108210611223857544

- DowlingJJVreedeAPKimSGoldenJFeldmanELKindlin-2 is required for myocyte elongation and is essential for myogenesisBMC Cell Biol200893618611274

- PluskotaEDowlingJJGordonNThe integrin coactivator kindlin-2 plays a critical role in angiogenesis in mice and zebrafishBlood2011117184978498721378273

- LarssonMDuffyDLZhuGGWAS findings for human iris patterns: associations with variants in genes that influence normal neuronal pattern developmentAm J Hum Genet201189233434321835309