Abstract

Background

Most studies focusing on improving the nutritional status of geriatric trauma patients exclude patients with cognitive impairment. These patients are especially at risk of malnutrition at admission and of worsening during the perioperative fasting period. This study was planned as a feasibility study to identify the difficulties involved in including this high-risk collective of cognitively impaired geriatric trauma patients.

Patients and methods

This prospective intervention study included cognitively impaired geriatric patients (Mini–Mental State Examination <25, age >65 years) with hip-related fractures. We assessed Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS 2002), body mass index, calf circumference, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification, and Braden Scale. All patients received parenteral nutritional supplementation of 800 kcal/d for the 96-hour perioperative period. Serum albumin and pseudocholinesterase were monitored. Information related to the study design and any complications in the clinical course were documented.

Results

A total of 96 patients were screened, among whom eleven women (median age: 87 years; age range: 74–91 years) and nine men (median age: 82 years; age range: 73–89 years) were included. The Mini–Mental State Examination score was 9.5 (0–24). All patients were manifestly undernourished or at risk according to MNA and NRS 2002. The body mass index was 23 kg/m2 (13–30 kg/m2), the calf circumference was 29.5 cm (18–34 cm), and the mean American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification status was 3 (2–4). Braden Scale showed 18 patients at high risk of developing pressure ulcers. In all, 12 patients had nonsurgical complications with 10% mortality. Albumin as well as pseudocholinesterase dropped significantly from admission to discharge. The study design proved to be feasible.

Conclusion

The testing of MNA and NRS 2002 was feasible. Cognitively impaired trauma patients proved to be especially at risk of malnutrition. Since 96 hours of parenteral nutrition as a crisis intervention was insufficient, additional supplementation could be considered. Laboratory and functional outcome parameters for measuring successive supplementation certainly need further evaluations involving randomized controlled trials.

Introduction

Owing to demographic changes, malnutrition is a continuing source of concern among older people.Citation1,Citation2 Data show that up to 55% of elderly hospitalized patients and up to 58% of patients with a hip fracture are undernourished on admission.Citation3–Citation6 Perioperative medical complications, perioperative periods of prolonged fasting while waiting for surgical treatment, and preexisting dementia may also restrict nutritional intake in the perioperative phase.Citation7,Citation8 It is estimated that ~30% of patients who sustain a hip fracture also have cognitive impairment.Citation9–Citation11 We know that, especially in cognitively impaired patients, oral food intake is challenging. During dementia progression, patients may no longer know what they are supposed to do with the food, and their eating skills are lost.Citation12 Thus, weight loss is a prominent clinical feature of dementia.Citation13,Citation14 There is evidence that the association between dementia and weight loss increases in the more severe stages of dementia.Citation15 There is also some evidence that a low body mass index (BMI) is associated with reduced survival and that older patients with dementia benefit from higher BMIs.Citation16,Citation17

For a large number of patients, poor nutritional status represents an underlying cause of falls and fractures.Citation18 According to a study by Eneroth et al,Citation19 the intake of energy during hospital stays is considerably lower than is needed. Postfracture loss of body mass and muscle strength causes further impairment of already impaired muscle function.Citation3 Furthermore, malnutrition has a strong negative impact on wound healingCitation20,Citation21 and is associated with prolonged hospital stays and higher mortality rates.Citation22 Thus, the improvement of patients’ nutritional status could help optimize care for geriatric trauma patients.

Many of the studies focusing on improving the nutritional status of geriatric trauma patients exclude patients with dementia or other kinds of cognitive impairment.Citation8,Citation19,Citation23 This is a common problem; in a recent review dealing with hip fracture patients, only 19 of 72 randomized controlled trial studies included both cognitively intact and impaired patients and only 14 reported the use of a validated cognitive assessment tool.Citation24

However, these patients are of particular interest, as they are at maximum risk of having malnutrition at admission and of worsening during the perioperative period. Studies focusing on nightly tube feeding have shown inconsistent results but have matched the reporting about some patients’ poor tolerance of nasogastric tubes.Citation25,Citation26 In the mentioned investigations, 25%–82% of included patients did not tolerate tubes until the end point of intervention. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines on nutrition in dementiaCitation27 suggest parenteral nutrition if there is an indication for artificial nutrition but tube feeding is contraindicated or not tolerated, if the period is shorter than 10 days, or if central venous line is already in place for other reasons.

In this pilot study, we assessed a treatment of 96 hours of perioperative parenteral nutrition with standardized energy intake in a sample of cognitively impaired geriatric hip fracture patients who were undernourished or at risk of malnutrition. This study was planned as a feasibility study to detect the specific problems and difficulties related to screening, inclusion, nutritional intervention, and outcome measurement in this fragile, high-risk group of cognitively impaired geriatric trauma patients.

Patients and methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Philipps University of Marburg (Ethikkomission der Universität Marburg), and written informed consent was obtained from participants or from their legal guardians.

The screening procedure of this prospective single-center intervention study included all geriatric patients (age 60 years or older) with proximal femoral fractures (ICD 10 S 72.0–72.2) admitted to our emergency department. The exclusion criteria were pathological fractures or malignancy-associated fractures, multiple traumas, contraindications for parenteral nutrition (such as a soy protein or peanut allergy), and severe liver impairment.

We included all patients identified as being cognitively impaired by Mini–Mental State Examination (<25)Citation28 in our prospective study design. Subsequently, we used two screening questionnaires, the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) Elderly and the 2002 version of the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS 2002) to detect malnutrition. We also measured patients’ BMI, calf circumference (CC), prefracture Barthel Index, and American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification status.Citation29 The type of surgery (osteosynthesis or prosthesis) and the lengths of the patients’ stays in the intensive care unit and in the hospital were documented.

If patients were identified as being at risk of malnutrition or as being manifestly malnourished, they received parenteral nutritional supplementation (SmofKabiven Peripheral; Fresenius Kabi Austria GmbH, Graz, Austria) offering 800 kcal/d as well as 1.206 L of fluid supplementation for the 96-hour perioperative period. Laboratory parameters such as albumin, pseudocholinesterase (PCHE), and triglycerides were monitored at admission and discharge, and additionally albumin and triglycerides were monitored once a day during the intervention.

Intervention-associated local complications (eg, increased rate of intravenous accesses or local infections) and systemic complications (eg, hypervolemia and elevated liver enzymes or fatty acids) were documented. Further local and systemic complications as well as hospital mortality were recorded. Prefracture mobility was measured using the new mobility score as a validated predictor of long-term mortality and rehabilitation outcome in patients with hip fractures.Citation30 The scores ranged between 0 and 3 (0, “not at all”; 1, “with help from another person”; 2, “with an aid”; and 3, “with no difficulty”) for each function, resulting in a total score from 0 (indicating no walking ability at all) to 9 (indicating full independence). Our physiotherapists scored postfracture mobilization by assessing the following grades: 0, “no mobilization”; 1, “sitting”; 2, “standing”; 3, “walking”; and 4, “climbing stairs.” The Timed Up and Go (TUG) testCitation31 was used as well, if possible. Risk stratification for decubital ulcers was done according to the Braden Scale.Citation32

We collected data in an Excel 2013 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). We used double entry with a plausibility check to improve data quality. We used Predictive Analytics SoftWare Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for descriptive statistics and explorative data analysis.

Results

We screened 96 patients; after identifying the patients who were cognitively impaired and who did not meet the exclusion criteria, we sought permission from the patients’ legal guardians for inclusion. As a result, 25 qualified patients were identified; five of them were excluded due to their moribund status or their lack of the required legal guardianship. The baseline is given in . The sample included eleven women (median age: 87 years; age range: 74–91 years) and nine men (median age: 82 years; age range: 73–89 years). The median Mini–Mental State Examination score at admission was 9.5 (range: 0–24). All patients in the sample were undernourished or at risk of malnutrition on one or both of the MNA or the NRS 2002. All the tests were interviewer administered, with the assistance of an accompanying relative or legal guardian. In some cases, such as for institutionalized patients, the relatives or legal guardians could not provide enough information. In these cases, the staff of the nursing home helped to acquire further information using their own knowledge or available medical records. The patients’ median BMI was 23 kg/m2 (range: 12.9–29.9 kg/m2), with five patients being overweight and four patients being underweight. The median CC was 29.5 cm (range: 18–34 cm). All patients who were underweight according to BMI had diminished CC. Another eight patients had CCs >30 cm. The mean Barthel Index was 40 (range: 20–95), and the mean American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification status was 3 (range: 2–4). Of the patients in the sample, three received prostheses and 17 received osteosynthesis. The mean hospital stay lasted 13 days (range: 7–17 days), including a mean of 1 day in the intensive care unit (range: 0–17 days). One patient spent 17 days in the intensive care unit before dying due to pneumonia and respiratory failure. The sample included 12 patients with nonsurgical complications (); the mortality rate was 10%.

Table 1 Baseline data

Table 2 Analytical separation of complications

Parenteral nutrition was started in all cases directly after admission and provided for 96 hours. Two patients did not tolerate peripheral venous line and therefore did not receive more than 48 hours of parenteral nutrition. The venous line was not replaced if a patient reacted with confusion or aggression (as in both cases mentioned earlier).

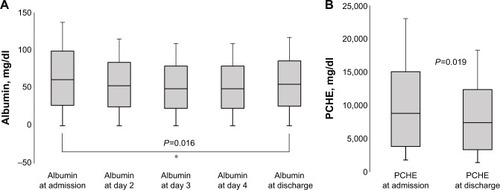

Hypoalbuminemia was defined as a serum albumin of <36 mg/dL.Citation33 The median albumin level was 34 mg/dL (range: 18–41 mg/dL) at admission and 29 mg/dL (range: 26–30 mg/dL) at discharge. This difference was statistically significant (; P=0.016). A similarly significant drop was detected in PCHE (). Triglycerides ranged mostly in physiological or mild elevated levels. None of the patients showed triglycerides >500 mmol/L; only one had two measurements >200 mmol/L. All other patients did not pass 200 mmol/L during the intervention. The complete amounts are given in .

Table 3 Analytical data of serological parameters

Figure 1 (A) Median albumin levels at admission; at days 2, 3, and 4 of nutritional supplementation; and at discharge. (B) Median PCHE = PCHE at admission and discharge.

Abbreviation: PCHE, pseudocholinesterase.

The median new mobility score for pretrauma mobility was only 0.5 (range: 0–5). Postoperative assessments showed that only one patient could perform the TUG test. The mobilization scores included some good results, with 15 patients achieving at least a standing position. The Braden Scale underlined the high risk of developing decubital ulcers, as 18 patients were in the high-risk group ().

Table 4 Outcome scores

Discussion

Although malnutrition is known to be a frequent finding in geriatric patients, data regarding cognitively impaired geriatric trauma patients are sparse, as this cohort is often excluded from nutritional supplementation studies.Citation20–Citation22

By present nutritional intervention pilot study, we aimed to detect the specific problems and difficulties related to screening, inclusion and nutritional intervention, and at least outcome measurement in this fragile, high-risk group of cognitively impaired geriatric trauma patients.

At first, some legal guardians were not available or not appointed at admission and therefore could not agree to participate at admission. Since ESPENCitation34 recommends screening for malnutrition to be an integrative part of geriatric assessment, including interventions for improvement of nutritional status in patients identified to be malnourished, a feasible study design for these patients should include the possibility for a subsequent approval when legal guardians are within reach.

Numerous tools are available in the literature to screen for malnutrition, but as mentioned in ESPEN’s guidelines on nutrition in dementia,Citation34 none of these tools have been specifically designed or validated for persons with dementia. Nevertheless, the MNA has shown wide acceptance among cognitively impaired patients, and the MNA Short Form has been validated especially for older people and is reported to be used frequently in populations both with and without dementia.Citation35–Citation38 Both of the screening tools used, the MNA and NRS 2002, are reported to be, especially, suitable for patients with proximal femoral fractures.Citation39 Nevertheless, information about a patient’s prefracture nutritional status was difficult and time consuming to determine when relatives were not present. Nevertheless, this could be accomplished in most cases, and since all the included patients were shown to be manifestly undernourished or at risk on at least one of the two tests, this study’s data underline the importance of this topic.

Furthermore, we tried to add information through anthropometric and serological screening parameters. Recent data showed that higher BMI is associated with decreased risk of mortality,Citation40 but simultaneously more obese and older patients are known to be more likely to develop adverse outcomes following a primary total hip replacement.Citation41 Concerning CC, a cutoff of 30.5 cm for both men and women is reported to provide a good diagnostic capacity.Citation42 Our results showed a correlation of CC among underweight patients (BMI <18 kg/m2) but not among all patients. Since some patients suffered from cardiac failure, peripheral edemas may have influenced these measurements.

Despite increasing evidence that hepatic protein levels do not depend only on nutritional intake, these proteins continue to be used to assess patients’ nutritional states and to diagnose malnutrition.Citation43,Citation44 Serum albumin levels at admission are known to be a significant independent predictor of complications in geriatric trauma patients.Citation29 In our collective, one of eleven patients showing hypoalbuminemia at admission died during the study. Keeping in mind that four patients were shown to be underweight according to BMI, three of these patients had hypoalbuminemia and all of them were at risk or malnourished according to MNA and NRS 2002. BMI and albumin proved not to be suitable as the sole screening parameters for malnutrition in our cohort. These findings are in line with the current literature reporting that in the perioperative situation, neither hypoalbuminemia nor BMI is reliable for the diagnosis of protein energy malnutrition.Citation45

The outcome parameters for the measurement of the success of short-term nutritional supplementation during hospitalization proved to be difficult to identify. Following patients’ protein levels in serum was feasible, but as albumin has a long half-life of 18–20 days,Citation46 it may have reduced sensitivity for detection of recent changes in the nutritional state.

Subsequently, we observed that short-term parenteral supplementation as a crisis intervention did not prevent patients’ albumin and PCHE levels from dropping during the 7–17 days between admission and submission. This finding is in line with other intervention studies.Citation47 Albumin shows an immediate response to surgical stress,Citation48–Citation50 and the findings of a recent pilot study suggest that postoperative albumin decrease reliably quantifies the magnitude of a surgery.Citation51 The underlying reasons for postoperative albumin decreases are summarized as an interplay of a decreased fractional synthesis rate, a capillary leak due to the metabolic stress response,Citation52–Citation54 and hemodilution as a potential confounder. Fractional albumin synthesis increases again during the early postoperative period proportionally to the degree of inflammation; additionally, production can be further stimulated by perioperative nutrition and nutrition being initiated before the operation, as done in our intervention. Recently, it has been published that isolated fracture of the femur elicits an inflammatory response in geriatric trauma patients similar to low injury severity in polytrauma patients.Citation55 This may explain the decrease in albumin levels that were observed in our high-risk cohort despite nutritional supplementation. Maybe additional oral nutritional supplements (ONS) would prove the effects, as ONS already proved beneficial in gaining weight in frail or malnourished patients. Nevertheless, improvement in functional status or mortality by ONS was not seen in hip fracture or demented populations.Citation56 In a meta-analysis of 22 trials, seven reported that nutritionally supplemented patients had shorter overall lengths of their hospital stays.Citation3 In line with other publications,Citation57–Citation59 the mean length of stay in our cohort was 13 days but as diagnosis-related groups system used in Germany requires a minimum of 13 days to determine the estimated costs of each stay, this parameter is difficult to interpret.Citation60 Since the TUG test requires no special equipment or training, we tried to assess it in our cohort. This failed due to prefracture immobility and cognitive decline, which caused patients to simply not understand the instructions. Finally, the intervention-related complications were sparse; we had only few patients who did not tolerate venous line and there was no catheter-associated infection. Severe hyperlipidemia did not occur. Therefore, we can recommend parenteral nutritional intervention as a safe and feasible perioperative crisis intervention but may be not sufficient without further aftercare in this collective.

Our pilot study had some limitations. First, our local ethical authorities allowed including only a small number of patients for pilot study. As we primarily aimed to detect the pitfalls in inclusion of cognitively impaired patients, we did not have a control group. Therefore, we could not compare clinical courses of our patients to those without intervention. Besides, we had ethical concerns, depriving patients classified as malnourished from nutritional supplementation. Finally, two patients were not able to complete more than 48 hours of parenteral nutrition; this may have biased the laboratory outcome parameters.

Conclusion

Summing up the mentioned findings, cognitively impaired trauma patients showed to be especially at risk of malnutrition and at high risk of developing decubital ulcers and experiencing a comparatively high rate of nonsurgical complications. MNA and NRS 2002 proved to be feasible screening methods for identifying these patients. Because 96 hours of parenteral nutrition alone failed to bring out a significant improvement in our cohort, additional application of ONS could be considered in further clinical courses. Laboratory and functional outcome parameters for measuring successive supplementation surely need further evaluations involving randomized controlled trials.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SullivanDHSunSWallsRCProtein-energy undernutrition among elderly hospitalized patients: a prospective studyJAMA1999281212013201910359390

- Royal College of PhysiciansNutrition and Patients: A Doctor’s ResponsibilityLondon, EnglandRoyal College of Physicians2003

- AvenellAHandollHHGNutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in older people (review)Cochrane Database Syst Rev20101186

- PaillaudEBoriesPNLe ParcoJCCampilloBNutritional status and energy expenditure in elderly patients with recent hip fracture during a 2-month follow-upBr J Nutr20008329710310743488

- McWhirterJPPenningtonCRIncidence and recognition of malnutrition in hospitalBMJ19943089459488173401

- WeekesEThe incidence of malnutrition in medical patients admitted to hospital in south LondonProc Nutr Soc199958126A

- FossNBJensenPSKehletHRisk factors for insufficient preoperative oral nutrition after hip fracture surgery within a multi-modal rehabilitation programAge Ageing200736553854317660529

- Koren-HakimTWeissAHershkovitzAThe relationship between nutritional status of hip fracture operated elderly patients and their functioning, comorbidity and outcomeClin Nutr201231691792122521470

- StenvallMBerggrenMLundstromMA multidisciplinary intervention program improved the outcome after hip fracture for people with dementia – subgroup analyses of a randomized controlled trialArch Gerontol Geriatr2012543e284e28921930310

- JuliebøVKrogsethMSkovlundEEngedalKRanhoffAHWyllerTBDelirium is not associated with mortality in elderly hip fracture patientsDement Geriatr Cogn Disord201030211212020733304

- LundströmMOlofssonBStenvallMPostoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention studyAging Clin Exp Res20071917818617607084

- ChangCCRobertsBLFeeding difficulty in older adults with dementiaJ Clin Nurs2008172266227418705703

- BelminJPractical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of weight loss in Alzheimer’s disease: a consensus from appropriateness ratings of a large expert panelJ Nutr Health Aging2007111333717315078

- WhiteHPieperCSchmaderKFillenbaumGWeight change in Alzheimer’s diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc19964432652728600194

- AlbaneseETaylorCSiervoMStewartRPrinceMJAcostaDDementia severity and weight loss: a comparison across eight cohorts. The 10/66 studyAlzheimers Dement20139664965623474042

- GambassiGLandiFLapaneKLSgadariAMorVBernabeiRPredictors of mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease living in nursing homesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1999671596510369823

- Faxen-IrvingGBasunHCederholmTNutritional and cognitive relationships and long-term mortality in patients with various dementia disordersAge Ageing200534213614115644407

- HedströmMLjungqvistOCederholmTMetabolism and catabolism in hip fracture patients: nutritional and anabolic intervention – a reviewActa Orthop200677574174717068704

- EnerothMOlssonUBThorngrenKGNutritional supplementation decreases hip fracture-related complicationsClin Orthop Relat Res200645121221716770284

- GheriniSVaughnBKLombardiAVMalloryTHDelayed wound healing and nutritional deficiencies after total hip arthroplastyClin Orthop Relat Res19932931881958339480

- RussellLThe importance of patients’ nutritional status in wound healingBr J Nurs2001106 supplS44S4912146181

- KovalKJMaurerSGSuETAharonoffGBZuckermanJDThe effects of nutritional status on outcome after hip fractureJ Orthop Trauma199913316416910206247

- AnbarRBelooseskyYCohenJTight calorie control in geriatric patients following hip fracture decreases complications: a randomized, controlled studyClin Nutr2014331232823642400

- MundiSChaudhryHBhandariMSystematic review on the inclusion of patients with cognitive impairment in hip fracture trials: a missed opportunity?Can J Surg2014574E141E14525078940

- BastowMDRawlingsJAllisonSPBenefits of supplementary tube feeding after fractured neck of femur: a randomized controlled trialBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)198327815891592

- SullivanDHNelsonCLKlimbergVSBoppMMNightly enteral nutrition support of elderly hip fracture patients: a pilot studyJ Am Coll Nutr200423668369115637216

- VolkertDChourdakisMFaxen-IrvingGESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementiaClin Nutr20153461052107326522922

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPRMini-Mental State (a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician)J Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- HaynesSRLawlerPGAn assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocationAnaesthesia1995503S195S199

- ParkerMJPalmerCRA new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fractureJ Bone Joint Surg Br1993757977988376443

- PodsiadloDRichardsonSThe timed “up & go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly personsJ Am Geriatr Soc19913921421481991946

- BergstromNBradenBJLaguzzaAHolmanVThe Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore riskV Nurs Res1987364205210

- GarweTAlbrechtRMStonerJAMitchellSMotgharePHypoalbuminemia at admission is associated with increased incidence of in-hospital complications in geriatric trauma patientsAm J Surg2015212110911526414690

- VolkertDChourdakisMFaxen-IrvingGESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementiaClin Nutr20153461052107326522922

- van Bokhorst-de van der SchuerenMAEGuaitoliPRJansmaEPde VetHCWNutrition screening tools: does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital settingClin Nutr2014331395823688831

- VandewoudeMVan GossumANutritional screening strategy in nonagenarians: the value of the MNA-SF (mini nutritional assessment short form) in NutriActionJ Nutr Health Aging201317431023538651

- PhillipsMBFoleyALBarnardRIsenringEAMillerMDNutritional screening in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic literature reviewAsia Pac J Clin Nutr201019344044920805090

- IsaiaGMondinoSGerminaraCMalnutrition in an elderly demented population living at homeArch Gerontol Geriatr201153324921236503

- MurphyMCBrooksCNNewSALumbersMLThe use of the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) tool in elderly orthopaedic patientsEur J Clin Nutr200054755556210918465

- Garcia-PtacekSKareholtIFarahmandBCuadradoMLReligaDEriksdotterMBody-mass index and mortality in incident dementia: a cohort study on 11,398 patients from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia RegistryJ Am Med Dir Assoc2014156447.e1447.e724721339

- MnatzaganianGRyanPNormanPEDavidsonDCHillerJEUse of routine hospital morbidity data together with weight and height of patients to predict in-hospital complications following total joint replacementBMC Health Serv Res20121238023116422

- BonnefoyMJauffretMKostkaTJusotJFUsefulness of calf circumference measurement in assessing the nutritional state of hospitalized elderly peopleGerontology200248316216911961370

- MoshageHJJanssenJAFranssenJHHafkenscheidJCYapSHStudy of the molecular mechanism of decreased liver synthesis of albumin in inflammationJ Clin Invest1987796163516413584463

- FuhrmanMPCharneyPMuellerCMHepatic proteins and nutrition assessmentJ Am Diet Assoc200410481258126415281044

- DrevetSBioteauCMazièreSPrevalence of protein-energy malnutrition in hospital patients over 75 years of age admitted for hip fractureOrthop Traumatol Surg Res2014100666967424998085

- FosterMRHeppenstallRBFriedenbergZBHozackWJA prospective assessment of nutritional status and complications in patients with fractures of the hipJ Orthop Trauma19904149572107289

- Botella-CarreteroJIIglesiasBBalsaJAZamarrónIArrietaFVázquezCEffects of oral nutritional supplements in normally nourished or mildly undernourished geriatric patients after surgery for hip fracture: a randomized clinical trialJPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr200832212012818407904

- SmeetsHJKievitJDulferFTHermansJMoolenaarAJAnalysis of post-operative hypalbuminaemia: a clinical studyInt Surg19947921521577928151

- RyanAMHeartyAPrichardRSCunninghamARowleySPReynoldsJVAssociation of hypoalbuminemia on the first postoperative day and complications following esophagectomyJ Gastrointest Surg200711101355136017682826

- FleckARainesGHawkerFIncreased vascular permeability: a major cause of hypoalbuminaemia in disease and injuryLancet198532584327817842858667

- HübnerMMantziariSDemartinesNPralongFCoti-BertrandPSchäferMPostoperative albumin drop is a marker for surgical stress and a predictor for clinical outcome: a pilot studyGastroenterol Res Pract20162016874318726880899

- FleckAColleyCMMyersMALiver export proteins and traumaBr Med Bull19854132652733896382

- HülshoffASchrickerTElgendyHHatzakorzianRLattermannRAlbumin synthesis in surgical patientsNutrition201329570370723333435

- RussellJAManagement of sepsisN Engl J Med2006355161699171317050894

- VesterHHuber-LangMSKidaQThe immune response after fracture trauma is different in old compared to young patientsImmun Ageing20141112025620994

- GammackJKSanfordAMCaloric supplements for the elderlyCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care2015181323625474011

- BueckingBWackCOberkircherLRuchholtzSEschbachDDo concomitant fractures with hip fractures influence complication rate and functional outcome?Clin Orthop Relat Res2012470123596360622707068

- EschbachDAOberkircherLBliemelCMohrJRuchholtzSBueckingBIncreased age is not associated with higher incidence of complications, longer stay in acute care hospital and in hospital mortality in geriatric hip fracture patientsMaturitas201374218518923218684

- AQUA [home page on the Internet]Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im GesundheitswesenBundesauswertung zum Erfassungsjahr 2011 17/1 – Hüftgelenksnahe FemurfrakturQualitätsindikatoren2012 Available from: http://www.aqua-institut.deAccessed May 31, 2012

- LawrenceTMWhiteCTWennRMoranCGThe current hospital costs of treating hip fracturesInjury200536889115589923