Abstract

Aging is an inevitable process and represents the accumulation of bodily alterations over time. Depression and chronic pain are highly prevalent in elderly populations. It is estimated that 13% of the elderly population will suffer simultaneously from the two conditions. Accumulating evidence suggests than neuroinflammation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of both depression and chronic pain. Apart from the common pathophysiological mechanisms, however, the two entities have several clinical links. Their management is challenging for the pain physician; however, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches are available and can be used when the two conditions are comorbid in the elderly patients.

Introduction

Aging is an inevitable process and represents the accumulation of bodily alterations over time.Citation1 These changes include both somatic and emotional maturity; however, many pathologic processes also occur as part of the aging process to the point that the latter is among the greatest risk factors for most diseases.Citation2

The emotional burden of the accumulated negative experiences might lead to depressed mood, which although might just be a normal reaction to events such as bereavement, it can also be a feature of depression.Citation3 The end-of-life development of depressive symptoms has been thoroughly investigated,Citation4 and it is unanimously accepted that depression is the most prevalent and the most treatable mental health problem in old age.Citation5 Apart from its major emotional impact, depression can atypically also cause somatic symptoms such as fatigue.Citation6

Chronic pain, on the other hand, has many similarities with depression in old age. Chronic pain is common; although it is predominantly a somatic symptom, it might also have a detrimental emotional element. Indeed, pain is a universal experience and the human body’s most valuable alerting system.Citation7 According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, it is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or is described in terms of such damage.Citation8 Recently, also because chronic pain is not perceived anymore as a simple symptom but as a disease in its own right, there is increasing interest in the relationship between this disease and the modifications of the nervous system.Citation9 Apparently, many other diseases of elderly people seem to be part of the same process of general “chronification”. Many of the researchers interested in gerontology, but also in neurology and pain, are convinced that the common pathogenic factor would be neuroinflammation.

This comprehensive review of the current literature aims to explore the clinical links between chronic pain and depression and also to discuss the management challenges for the clinician when the two conditions are comorbid in the elderly patients. It will also analyze in depth the potentiality that neuroinflammation could represent the common element that put together the two pathologies: pain and depression.

Phenomenology and diagnostic challenges

Depression versus mild cognitive impairment

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the overall global burden of any disease.Citation10 The World Health Organization estimates that ~350 million people suffer from depression, while over 800,000 people die because of suicide every year.Citation11

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, a diagnosis of a major depressive disorder requires presence of symptoms such as depressed mood, sleep cycle disturbances, fatigue and poor concentration for at least 2 weeks, causing clinically significant distress or impairment in social functioning.Citation12 However, occult depressive-like behaviors remain a challenge to the clinician, especially because such behaviors are often manifestations of an underlying premature cognitive dysfunction.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) describes the gray zone between a normal cognitive function and dementia. Individuals with MCI can also experience difficulties in memory, language, thinking skills or judgment (4AD).Citation13 These difficulties, however, are not severe enough to interfere with daily life or independent functionality. The National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association defines MCI as the change in cognition reported by the patient or clinician, as well as objective evidence of impairment in one or more cognitive domains with preserved functionality.Citation14,Citation15

More than often, apathy, withdrawal and self-neglect are the first symptoms of MCI. Patients with neurodegenerative diseases, including MCI, have a difficulty in reporting their symptoms accurately. For example, instead of reporting or being able to recognize the feeling of sadness, they might present with anxiety.Citation12 Similarly, assessment of pain in people with dementia is particularly challenging because of the loss of communication ability, which limits the subjective reporting of pain that would normally be expected with cognitively healthy adults.Citation16

The relationship between depression and cognitive dysfunction is very complicated and not well decoded so far. Indeed, symptoms and clinical presentation often overlap, so clinicians face a challenging decision when it comes to choosing the appropriate treatment strategy.

Types and causes of chronic pain in the elderly

The distinction between acute and chronic pain is often determined by an arbitrary interval of time since onset, with the most commonly used marker being 3 months from its first appearance.Citation17 Further classification of pain is based on the clinical characteristics and etiology.

Neuropathic pain, nociceptive pain and mixed pain definitions

A broad categorization of pain which is useful in clinical practice is nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Nociceptive pain is the pain that arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors, while neuropathic pain is defined as the pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.Citation18 However, not uncommonly, chronic pain is the result of both neuropathic as well as nociceptive mechanisms and can be classified as a mixed pain syndrome on these occasions.Citation19

Causes of chronic pain in the elderly

A clinically useful categorization of pain syndromes based on the underlying etiology is the one proposed in the new version of the International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision, according to which pain syndromes can be classified into seven groups:Citation17

Chronic cancer pain: is caused either directly by the cancer (primary tumor invasion or metastases) or indirectly by the treatment (ie, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and radiotherapy).Citation20

Chronic neuropathic pain: is caused by any lesion in the somatosensory nervous system (ie, thalamic stroke, peripheral neuropathy and radiculopathy). Neuropathy is highly prevalent in old age,Citation21 and common causes of painful neuropathies include diabetic neuropathy,Citation22 alcohol-related neuropathy,Citation23 gluten neuropathyCitation24 and entrapment neuropathies.Citation25 However, up to one-third of neuropathies, which can be painful as well, will remain idiopathic (of unknown etiology) despite extensive investigations.Citation26

Chronic musculoskeletal pain: arises as part of diseases directly affecting the bones (ie, fractures), joints (ie, inflammatory and degenerative arthritis), muscles (ie, myositis) or related soft tissues (ie, tendonitis). Occasionally, chronic musculoskeletal pain can indirectly arise as part of diseases, because of bad posturing (ie, Parkinson’s disease).Citation27–Citation30

Chronic post-traumatic or postsurgical pain: is a definition by exclusion, when other causes of pain as well as a pre-existing pain syndrome are excluded and the patient suffers from pain that has developed after a surgical operation or a traumatic lesion.Citation17

Chronic visceral pain: is a predominantly nociceptive pain which originates from the internal organs, commonly because of inflammation (eg, chronic pancreatitis),Citation31 ischemic lesions (ie, chronic mesenteric ischemia)Citation32 or obstruction (ie, bowel obstruction).Citation33

Chronic headache and orofacial pain: This subcategory includes chronic headaches, which are not further discussed in this review, as the aim of this paper is to focus on the chronic-bodily pain and orofacial pain syndromes. The latter can be purely neuropathic secondary to cranial neuropathies (ie, trigeminal neuralgia)Citation34 or predominantly nociceptive secondary to temporomandibular disorders.Citation35

Chronic primary pain is a pain syndrome that cannot be explained by another chronic pain condition. In this category, syndromes such as low back pain,Citation36 identified as neither musculoskeletal nor neuropathic, can be found, as well as painful conditions causing significant emotional distress, such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.Citation37

summarizes the pain syndromes, their major causes and their pain characteristics.

Table 1 Pain syndromes, major causes and types of pain

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of depression in the elderly

In 2015, 12.3% of the world population consisted of people aged 60 or over.Citation38 This percentage will almost double by 2050 as by then, 21.5% of the world population will consist of people aged 60 or over.Citation38 This percentage increased further to 32.8% in the more developed regions.Citation38 Because of this and the increased life expectancy, numerous studies focusing on the epidemiology of the diseases of the aging population have been conducted.

Current estimates vary significantly from 4.3% in ChinaCitation39 to 63% in Korea.Citation40 These figures, though, should be interpreted with extreme caution, as the gold standard for diagnosing depression is not similar since some studies use only screening questionnairesCitation40–Citation44 while other studies use proper psychiatric interviews. Also, there is a significant selection bias of the studied population, as some studies have been conducted in nursing homes,Citation45 rehabilitation environment,Citation42 inpatientsCitation46 or community.Citation39,Citation40,Citation47,Citation48

In a recent meta-analysis focusing on the prevalence of depression, Volkert et alCitation49 estimated that the lifetime prevalence of major depression in people 50 years or older in the western countries is 16.5%. Solhaug et alCitation50 conducted a prospective cohort study and showed that the incidence of depression increases with age. This is one of the elements that make clear a relationship between at least some of the chronic pathologies of the elderly.

Although the prevalence varies significantly across countries and different elderly populations, the majority of studies concluded that depression in the elderly is highly associated with poorer cognitive status,Citation47 higher number of medical problems,Citation39,Citation48,Citation51 more severe disabilityCitation44,Citation52 and lower socioeconomic status.Citation44

Epidemiology of chronic pain in the elderly

The prevalence of chronic pain in the general population shows high variability mainly because of the differences across the studied populations and the methodology of the studies.Citation53 Heterogeneity in prevalence is also secondary to variable definitions of pain chronicity.Citation54 Over the last years, the methodology has improved significantly, as the studies are now population based (with the participants being representative of the general population), the duration criterion has been set to be pain of at least 3 months duration and the presence of pain and its characteristics has been evaluated by validated questionnaires. Based on these population studies,Citation55–Citation72 the prevalence of chronic pain in the general population is estimated to range from 15.1% in CanadaCitation66 to 48.9% in Sweden.Citation72 The majority, if not all, of these studies have identified female gender and age as the risk factors for developing chronic pain. Poor education and low socioeconomic status have been also identified as significant risk factors.

Data from general population studies have shown the prevalence of chronic pain in the elderly can be as high as 55% after the age of 60 yearsCitation67 and as high as 62% after the age of 75 years.Citation56 The prevalence of chronic pain remains the same in the age group 60–74 and the age group >75, however the data for this statement are limited.Citation67

Few studies have specifically looked into the elderly,Citation73–Citation80 and similar to the epidemiologic studies of the prevalence of chronic pain in the general population, the prevalence of chronic pain in the elderly also varies widely from 15.2% in MalaysiaCitation77 to 69.8% in Germany.Citation79 This percentage is even higher (up to 83%) among the elderly people living in nursing homes.Citation81,Citation82 This is expected, as people in nursing homes are less healthy and not representative of the general population. Also, similar to the general population studies, female gender, obesity and poor economic status are the risk factors for chronic pain in the elderly.

The commonest type of pain in the elderly is back pain;Citation74,Citation76 however, not many large studies of prevalence of the specific subtype and the etiology of pain have been conducted in the elderly.

Comorbidity of depression and chronic pain in the elderly

In some general populations, epidemiologic studies have shown that chronic pain increases the risk for depression between 2.5 and 4.1 times.Citation75,Citation79 Similarly, patients suffering from a major depressive disorder are three times more likely to suffer from non-neuropathic pain and six times more likely to suffer from neuropathic pain.Citation61 These data contribute to the hypothesis that the common pathogenic factor between chronic pain and depression could be represented by the chronic, subclinical, neuroinflammation.

As both depression and chronic pain are prevalent in the elderly, coexistence of the two entities is not uncommon.Citation83–Citation86 Using validated tools for the diagnosis of depression, it has been shown that 13% of the elderly suffer from both depression and chronic pain.Citation87

Pain severity is strongly associated with depression in the elderly, whereas this association is not demonstrated in younger people.Citation81,Citation88 Female gender is strongly associated with the comorbidity of the two entities, with women being more likely to suffer from chronic pain if they also suffer from depression.Citation89

Only limited data are available about the risk for depression based on the anatomic sites of pain. In one study, it was shown that chronic chest pain was independently associated with depression, while pain in other locations such as neck, back or joint pain was not.Citation90 No large studies have been published to date about the subtypes of chronic pain and their relation to depression in the elderly.

Perception of pain and the role of depression

Pain perception varies significantly among patients and is sensitive to various factors including genetic predispositionCitation91 and gender, with female patients experiencing greater clinical pain, suffering greater pain-related distress and showing heightened sensitivity to experimentally induced pain compared with men.Citation92 Also, perception of pain is sensitive to various mental processes such as the feelings and beliefs that someone has about pain.Citation93 It is, therefore, not exclusively driven by the noxious input.Citation93

A cognitive behavioral model has been proposed to explain the role of cognitive appraisal variables in mediating the development of emotional distress following pain of long duration. There is little evidence linking the prevalence of depression in chronic pain patients to life stage, but there are suggestions in the literature that the link between medical illness and depression may be stronger in elderly patients.Citation88

Although it was initially suggested that depressed subjects are less likely to perceive an experimental sensory stimulus as being painful compared with nondepressed controls,Citation94 subsequent studies showed that painful stimuli are processed differentially, depending on the localization of pain induction in depression.Citation95 Klauenberg et alCitation96 showed that in pain-free patients, signs of an enhanced central hyperexcitability are even more pronounced than usually found in chronic pain patients, indicating common mechanisms in depressive disorder and chronic pain in accordance with the assumption of non-pain-associated mechanisms in depressive disorder for central hyperexcitability, for example, by inhibited serotonergic function. Again, the common mechanism could be represented by neuroinflammation.

In a recent meta-analysis of experimental studies, Thompson et alCitation97 concluded that potential effects of depression on pain perception are variable and likely to depend upon multiple factors, including the stimulus modality. This conclusion could help explain the discrepancies across clinical and experimental findings;Citation97 however, further studies on the links between depression and pain perception area are needed in all age groups, including the elderly.

The role of neuroinflammation

In the last decades, a dramatic revolution within the scope of neurosciences and underlying immunologic mechanisms has been documented. The concept of central nervous system (CNS) immune privilege had been enormously questioned, as long as an ongoing scientific work managed to illustrate a clear interaction between CNS and the peripheral inflammatory response.Citation98 The congenital defensive system of the host, composed of the blood–brain barrier, cellular and molecular components, provides an immediate answer to pathogen-associated molecular patterns,Citation99 while the adaptive system produces a delayed, highly specialized response and also creates immunologic memory. Indeed, it begins as a beneficial process; however, an excessive and unresolved reply could have harmful outcome.Citation100

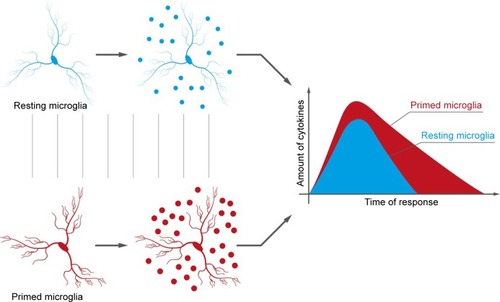

In chronic pain, neuroinflammation is often the result of peripheral damage and excessive neuronal activity of primary sensory neurons.Citation13 Glia and mast cells are the main coplayers of the somatosensory system,Citation101 while their miscommunication promotes impaired neuronal cell functionality. Microglia, in particular, are the main resident macrophage-like cells of the CNS. Their activation is quite a complex process that results in several phenotypes.Citation102 Interestingly, during chronic inflammation, microglia may exist in a range of phenotypic states. Specifically, in the aging brain, microglia are mostly present in a “primed” phenotype (),Citation103 meaning they are primed by previous pathology, or by genetic predisposition, to respond more vigorously to subsequent inflammatory stimulation.Citation104,Citation105 Recently, Loggia et alCitation106 documented in vivo the predominantly thalamic occurrence of glial activation, as measured by an increase in 11C-PBR28 binding using positron emission tomography-magnetic resonance imaging, in patients with chronic low back pain.

Figure 1 The differences between normal and “primed” microglia consist of an increased sensibility of the latter to any kind of stimulation. The consequence is an increased production of cytokines.

In addition, the mast cells make an essential contribution to the inflammatory process. Mast cells represent a potentially significant peripheral immune signaling link to the brain.Citation105 The increased endoneural number and their progressive hyperreactivity with age play a major role in the determination of the altered functionality of the pain receptors and the pain primary fibers.Citation9 Mast cell degranulation is known to activate pain pathways and elicit tactile pain hypersensitivity, possibly by releasing substances that interfere with or sensitize nociceptors.Citation105

Moreover, there is evidence that inflammation in the CNS may contribute to pain sensitization and chronification. In regards to neuropathic pain, human studies investigating cytokine profiles in the cerebrospinal fluid have indicated that it may be the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles.Citation107

Similarly, it has been proposed that the inflammatory processes in depression induce alterations of immune regulation in the CNS.Citation108 High corticosterone levels and peripheral increased expression of cytokines that are actively transported into the CNS may lead to microglia and astrocyte stimulation, which in turn produce further cytokines through a feedback mechanism.Citation109 This activation may then promote the suppression of neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, further enhancing the development of depression-like symptoms, suggesting that a prior inflammation may set the basis for the emergence of depression.Citation110

Since chronic pain and depression coexist with such high prevalence, it is rational to hypothesize that common underlying pathogenic mechanisms might exist.Citation107

Management

Managing an elderly patient with comorbid chronic pain and depression is often a challenge. Of course, a patient might receive treatment for each condition separately based on the relevant guidelines; however, there are pharmacologic and some nonpharmacologic approaches worth considering.

Pharmacologic approaches targeting both depression and chronic pain

Evidence to date indicates that pharmacotherapy focused on both depression and chronic pain in older adults may yield superior outcomes than focusing on only one condition.Citation111–Citation113

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Although there is no ideal antidepressant in the elderly, in general, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are tolerated better than others. However, SSRIs increase the risk of gastrointestinal and other bleeds (such as hemorrhagic stroke), particularly in the very elderly and those with established risk factors, and therefore should be used with caution.Citation114 Only a few trials of SSRIs have been conducted in the management of chronic pain. Fluoxetine was found to relieve low back pain and whiplash-associated cervical pain.Citation114 Also, fluoxetine was found to improve the overall quality of chronic pain; however, this observation depended more on an improvement in depressive symptoms of the patients.Citation115 Similarly, Aragona et alCitation116 showed that citalopram may have a moderate analgesic effect in patients with pain, and that this analgesic activity appeared to be not correlated to changes in depressive scores. Shimodozono et alCitation117 showed that fluvoxamine is useful for the control of central post-stroke pain, regardless of depression, when used relatively early after stroke. The therapeutic effect of fluvoxamine on the neuropathic component of pain was also observed by Ciaramella et al.Citation115 Finally, a placebo-controlled trial of sertraline showed a significant improvement in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome.Citation118

Although there are some reports supporting the effectiveness of SSRIs in the management of pain, they are few in number. Replication of larger randomized controlled trials is needed to prove the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of pain in the general population and in the elderly.

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Duloxetine is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor which has been shown to be effective both as an antidepressant and for chronic pain in the elderly.Citation119 The analgesic effect includes both its effect on neuropathic pain, such as pain secondary to diabetic neuropathy,Citation120 and in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain.Citation121

Venlafaxine is a safe and well-tolerated serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that can be used for the symptomatic treatment of neuropathic pain.Citation122 Venlafaxine exerts its effects on the modulation of spinal nociceptive transmission, which may reflect changes in balance between descending inhibition and descending facilitation.Citation123 Experimental rat studies showed that when venlafaxine is administered as an adjuvant to tramadol, additive action in reducing hyperalgesia and allodynia has been observed.Citation124 However, a study conducted by Cegielska-Perun et alCitation125 has shown that whereas acute coadministration of venlafaxine increases the analgesic activity of morphine, chronic treatment with venlafaxine attenuates opioid efficacy.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline, clomipramine and nortriptyline are the most commonly used tricyclic antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants can decrease the pain perception,Citation126 and are used in various forms of pain including cancer pain,Citation126 orofacial pain,Citation127,Citation128 fibromyalgia,Citation129 central neuropathic painCitation130 and peripheral neuropathic pain.Citation131 In the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain, amitriptyline and nortriptyline have equivalent overall adverse effects and discontinuation rates, and both can be equally considered either as monotherapy or as part of combination therapy.Citation131 For the treatment of central pain, clomipramine is significantly more effective compared to nortriptyline.Citation130

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants

Mirtazapine is the most commonly used antidepressant in this category. It has been shown that mirtazapine can increase the pain tolerance in healthy people.Citation132 Yet, limited studies of the effectiveness of mirtazapine in pain are available. In an open-label crossover trial, it was shown that mirtazapine might relieve pain in cancer patients.Citation133

Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

Buproprion is primarily used as an antidepressant and smoking cessation aid. No human studies of its analgesic properties have been conducted; however, a study in mice showed that it has a significant antiallodynic effects.Citation134

Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors

Trazodone is the most commonly used antidepressant in this category. Trazodone is equally efficacious to amitriptyline in cancer pain,Citation135 and it is efficacious in fibromyalgia.Citation136 However, no therapeutic effect was shown in chronic low back painCitation137 and orofacial pain.Citation138

Nonpharmacologic approaches targeting both depression and chronic pain

Psychotherapeutic approaches

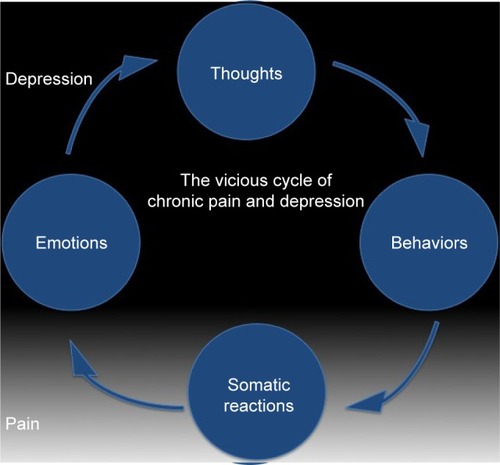

A vicious cycle of chronic pain and depression () involved a constant interaction between cognitions (thoughts), behaviors, somatic reactions (ie, pain) and emotions. As pain has cognitive and emotional components, a psychotherapeutic approach to its management can be justified. Reappraisal of the negative experiences of pain can lead to reduction of pain perception. Recent studies have observed that brain activation is more related to the intensity of expected pain than to the real intensity of the noxious stimuli. In other words, positive expectations reduce the severity of pain perception.Citation139 Reformulating the significance of an event and reinterpreting its meaning is the principal aim of any psychotherapeutic intervention. A number of psychotherapeutic and adjunctive techniques can, therefore, be used to address the psychological and social features associated with and contributing to pain.Citation111,Citation139

Figure 2 Relationship between chronic pain and depression, and the vicious cycle existing between the two pathologies.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has demonstrated clinical benefit for both depression and chronic pain.Citation140–Citation143 CBT for chronic pain and major depressive disorder utilizes similar techniques such as learning to pace activities, reinforcement of adaptive responses, reframing cognitive responses, learning coping and problem-solving skills, and relaxation techniques.Citation144,Citation145

Computerized CBT programs are also becoming increasingly availableCitation146 and should be considered for elderly patients who are computer savvy and/or have limited access to mental health care. A recent meta-analysis examined the effect of computerized CBT on chronic pain and concluded that web-based interventions for chronic pain yield small reduction in pain in the intervention group compared with the waiting-list control groups.Citation147

Acceptance and commitment therapy is another form of psychotherapy that can be used in depression and chronic pain. Several studies have shown that greater acceptance of pain is associated with reports of lower pain intensity, less pain-related anxiety and avoidance, less depression, less physical and psychosocial disability, and greater physical and social ability.Citation148,Citation149

Brief psychodynamic approach is usually combined with psychopharmacologic treatments for the treatment of elderly patients with oncologic pain. It has demonstrated a significant reduction in pain perception and depression, when compared to the pharmacologic treatment alone.Citation150

Acupuncture

Accumulating evidence suggests that acupuncture can be very effective in the treatment of chronic pain and depression, even in the primary care.Citation151 Usually, acupuncture is used as an adjuvant approach, and it has been shown that it is effective in both reducing depression and pain, compared to counseling or usual care alone.Citation152

Other nonpharmacologic approaches

Good quality studies on other nonpharmacologic approaches are lacking; however, some reports suggest that hypnotherapy,Citation153 physical exerciseCitation154 and relaxation techniquesCitation155 might be helpful in targeting depression and pain.

Conclusion

This review indicates the following key points:

Both chronic pain and depression are prevalent in old age and they have a bidirectional relationship. Both depression and pain might be risk factors for each other.

Robust epidemiologic data focusing on the prevalence of chronic pain subtypes and comorbid depression are lacking. Epidemiologic studies from different countries are not only of help to tailor management strategies, but also useful in understanding other underlying risk factors, which may account for the wide range of prevalence of chronic pain and depression in the elderly that has been reported so far.

There is increasing evidence of the role of neuroinflammation for the development of both chronic pain and depression.

Pharmacologic studies of antidepressant agents targeting chronic pain and depression simultaneously are lacking, especially in the elderly populations.

The role of nonpharmacologic approaches in the management of pain and depression is increasingly drawing attention. These approaches not only include psychotherapeutic interventions, but also acupuncture, hypnotherapy, physical exercise and relaxation techniques. However, better quality studies would be necessary.

The patient should always be part of the decision making in terms of management. With numerous pharmacologic agents and nonpharmacologic approaches in their armamentarium, the pain physicians can tailor the treatment based on each patient’s needs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WallaceDCThe inevitability of growing oldJ Chronic Dis19672074754866028267

- NiccoliTPartridgeLAgeing as a risk factor for diseaseCurr Biol20122217R741R75222975005

- MaerckerAForstmeierSEnzlerAAdjustment disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depressive disorders in old age: findings from a community surveyCompr Psychiatry200849211312018243882

- DiegelmannMSchillingOKWahlHWFeeling blue at the end of life: trajectories of depressive symptoms from a distance-to-death perspectivePsychol Aging201631767268627684104

- AndersonDNTreating depression in old age: the reasons to be positiveAge Ageing20013011317

- SmithORKupperNSchifferAADenolletJSomatic depression predicts mortality in chronic heart failure: can this be explained by covarying symptoms of fatigue?Psychosom Med201274545946322511727

- SykiotiPZisPVadaloucaAValidation of the Greek Version of the DN4 diagnostic questionnaire for neuropathic painPain Pract201515762763224796220

- Classification of chronic painDescriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on TaxonomyPain Suppl19863S1S2263461421

- VarrassiGFuscoMCoaccioliSPaladiniAChronic pain and neurodegenerative processes in elderly peoplePain Pract20151511325353291

- FerrariAJCharlsonFJNormanREBurden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010PLoS Med20131011e100154724223526

- World Health Organization. Media CentreDepression Fact Sheet Reviewed April2016 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/Accessed February 1, 2017

- BaqueroMMartínNDepressive symptoms in neurodegenerative diseasesWorld J Clin Cases20153868269326301229

- JiRRXuZZGaoYJEmerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic painNat Rev Drug Discov201413753354824948120

- PetersenRCCaraccioloBBrayneCGauthierSJelicVFratiglioniLMild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolutionJ Intern Med2014275321422824605806

- PalmerKBergerAKMonasteroRWinbladBBäckmanLFratiglioniLPredictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer diseaseNeurology200768191596160217485646

- AchterbergWPPieperMJvan Dalen-KokAHPain management in patients with dementiaClin Interv Aging201381471148224204133

- TreedeRDRiefWBarkeAA classification of chronic pain for ICD-11Pain201515661003100725844555

- TreedeRDJensenTSCampbellJNNeuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposesNeurology200870181630163518003941

- BaronRBinderAHow neuropathic is sciatica? The mixed pain conceptOrthopade2004335568575 German15067505

- VadaloucaARaptisEMokaEZisPSykiotiPSiafakaIPharmacological treatment of neuropathic cancer pain: a comprehensive review of the current literaturePain Pract201212321925121797961

- HanewinckelRDrenthenJvan OijenMHofmanAvan DoornPAIkramMAPrevalence of polyneuropathy in the general middle-aged and elderly populationNeurology201687181892189827683845

- SchreiberAKNonesCFReisRCChichorroJGCunhaJMDiabetic neuropathic pain: physiopathology and treatmentWorld J Diabetes20156343244425897354

- ChopraKTiwariVAlcoholic neuropathy: possible mechanisms and future treatment possibilitiesBr J Clin Pharmacol201273334836221988193

- HadjivassiliouMGrünewaldRAKandlerRHNeuropathy associated with gluten sensitivityJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200677111262126616835287

- ZisPZisVXirouSKemanetzoglouEZambelisTKarandreasNRapid screening for carpal tunnel syndrome: a novel method and comparison with established othersJ Clin Neurophysiol201532437537926241247

- ZisPSarrigiannisPGRaoDGHewamaddumaCHadjivassiliouMChronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy: a systematic reviewJ Neurol2016263101903191026961897

- ZisPRizosAMartinez-MartinPNon-motor symptoms profile and burden in drug naïve versus long-term Parkinson’s disease patientsJ Parkinsons Dis20144354154724927755

- ZisPMartinez-MartinPSauerbierANon-motor symptoms burden in treated and untreated early Parkinson’s disease patients: argument for non-motor subtypesEur J Neurol20152281145115025981492

- ZisPSokolovEChaudhuriKRAn overview of pain in Parkinson’sBattagliaAAAn Introduction to Pain and Its Relation to Nervous System DisordersUKJohn Wiley & Sons2016387

- ZisPErroRWaltonCCSauerbierAChaudhuriKRThe range and nature of non-motor symptoms in drug-naive Parkinson’s disease patients: a state-of-the-art systematic reviewParkinson’s Disease2015115013

- GulloLSipahiHMPezzilliRPancreatitis in the elderlyJ Clin Gastroenterol199419164687930438

- HohenwalterEJChronic mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis and treatmentSemin Intervent Radiol200926434535121326544

- MillerGBomanJShrierIGordonPHNatural history of patients with adhesive small bowel obstructionBr J Surg20008791240124710971435

- StavropoulouEArgyraEZisPVadaloucaASiafakaIThe effect of intravenous lidocaine on trigeminal neuralgia: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trialISRN Pain2014201485382627335883

- SchiffmanEOhrbachRTrueloveEInternational RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental ResearchOrofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of PainDiagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD consortium network* and orofacial pain special interest groupJ Oral Facial Pain Headache201428162724482784

- ZisPBernaliNArgiraESiafakaIVadaloukaAEffectiveness and impact of capsaicin 8% patch on quality of life in patients with lumbosacral pain: an open-label studyPain Physician2016197E1049E105327676676

- ZisPBrozouVStavropoulouEValidation of the Greek Version of the fibromyalgia rapid screening toolPain Pract Epub20161220

- United NationsWorld population ageing2015Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York, NYUnited Nations2015

- MaXXiangYTLiSRPrevalence and sociodemographic correlates of depression in an elderly population living with family members in Beijing, ChinaPsychol Med200838121723173018366820

- KimJIChoeMAChaeYRPrevalence and predictors of geriatric depression in community-dwelling elderlyAsian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci)20093312112925030470

- WongSYMercerSWWooJLeungJThe influence of multi-morbidity and self-reported socio-economic standing on the prevalence of depression in an elderly Hong Kong populationBMC Public Health2008811918410677

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJPrevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in elderly patients admitted in post-acute intermediate careInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200823111141114718457336

- HelvikASSkanckeRHSelbaekGScreening for depression in elderly medical inpatients from rural area of Norway: prevalence and associated factorsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201025215015919551706

- ImranAAzidahAKAsreneeARRosedianiMPrevalence of depression and its associated factors among elderly patients in outpatient clinic of Universiti Sains Malaysia HospitalMed J Malaysia200964213413920058573

- LevinCAWeiWAkincigilALucasJABilderSCrystalSPrevalence and treatment of diagnosed depression among elderly nursing home residents in OhioJ Am Med Dir Assoc20078958559417998115

- MichopoulosIDouzenisAGournellisRMajor depression in elderly medical inpatients in Greece, prevalence and identificationAging Clin Exp Res201022214815120440101

- BaiyewuOSmith-GambleVLaneKAPrevalence estimates of depression in elderly community-dwelling African Americans in Indianapolis and Yoruba in Ibadan, NigeriaInt Psychogeriatr200719467968917506912

- RajkumarAPThangaduraiPSenthilkumarPGayathriKPrinceMJacobKSNature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian communityInt Psychogeriatr200921237237819243657

- VolkertJSchulzHHärterMWlodarczykOAndreasSThe prevalence of mental disorders in older people in Western countries – a meta-analysisAgeing Res Rev201312133935323000171

- SolhaugHIRomuldEBRomildUStordalEIncreased prevalence of depression in cohorts of the elderly: an 11-year follow-up in the general population – the HUNT studyInt Psychogeriatr201224115115821767455

- GanatraHAZafarSNQidwaiWRoziSPrevalence and predictors of depression among an elderly population of PakistanAging Ment Health200812334935618728948

- HornstenCMolanderLGustafsonYThe prevalence of stroke and the association between stroke and depression among a very old populationArch Gerontol Geriatr201255355555922647381

- SchopflocherDTaenzerPJoveyRThe prevalence of chronic pain in CanadaPain Res Manag201116644545022184555

- JacksonTThomasSStabileVHanXShotwellMMcQueenKPrevalence of chronic pain in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet2015385Suppl 2S10

- Leão FerreiraKABastosTRAndradeDCPrevalence of chronic pain in a metropolitan area of a developing country: a population-based studyArq Neuropsiquiatr2016741299099827991997

- CheungCWChoiSWWongSSLeeYIrwinMGChanges in prevalence, outcomes, and help-seeking behavior of chronic pain in an aging population over the last decadePain Pract Epub20161013

- FayazACroftPLangfordRMDonaldsonLJJonesGTPrevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studiesBMJ Open201666e010364

- DueñasMSalazarAOjedaBA nationwide study of chronic pain prevalence in the general spanish population: identifying clinical subgroups through cluster analysisPain Med201516481182225530229

- CabralDMBracherESDepintorJDEluf-NetoJChronic pain prevalence and associated factors in a segment of the population of São Paulo CityJ Pain201415111081109125038400

- HäuserWWolfeFHenningsenPSchmutzerGBrählerEHinzAUntying chronic pain: prevalence and societal burden of chronic pain stages in the general population – a cross-sectional surveyBMC Public Health20141435224725286

- OhayonMMStinglJCPrevalence and comorbidity of chronic pain in the German general populationJ Psychiatr Res201246444445022265888

- JacksonTChenHIezziTYeeMChenFPrevalence and correlates of chronic pain in a random population study of adults in Chongqing, ChinaClin J Pain201430434635223887340

- HarifiGAmineMAit OuazarMPrevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the Moroccan general population: a national surveyPain Med201314228729223241023

- AzevedoLFCosta-PereiraAMendonçaLDiasCCCastro-LopesJMEpidemiology of chronic pain: a population-based nationwide study on its prevalence, characteristics and associated disability in PortugalJ Pain201213877378322858343

- ReitsmaMTranmerJEBuchananDMVanDenKerkhofEGThe epidemiology of chronic pain in Canadian men and women between 1994 and 2007: longitudinal results of the National Population Health SurveyPain Res Manag201217316617222606681

- ReitsmaMLTranmerJEBuchananDMVandenkerkhofEGThe prevalence of chronic pain and pain-related interference in the Canadian population from 1994 to 2008Chronic Dis Inj Can201131415716421978639

- JakobssonUThe epidemiology of chronic pain in a general population: results of a survey in southern SwedenScand J Rheumatol201039542142920476853

- SáKBaptistaAFMatosMALessaIPrevalence of chronic pain and associated factors in the population of Salvador, BahiaRev Saude Publica2009434622630 English, Portuguese19488666

- BouhassiraDLantéri-MinetMAttalNLaurentBTouboulCPrevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general populationPain2008136338038717888574

- TorranceNSmithBHBennettMILeeAJThe epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population surveyJ Pain20067428128916618472

- RustøenTWahlAKHanestadBRLerdalAPaulSMiaskowskiCPrevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the general Norwegian populationEur J Pain20048655556515531224

- GerdleBBjörkJHenrikssonCBengtssonAPrevalence of current and chronic pain and their influences upon work and healthcare-seeking: a population studyJ Rheumatol20043171399140615229963

- dos SantosFAde SouzaJBAntesDLd’OrsiEPrevalence of chronic pain and its association with the sociodemographic situation and physical activity in leisure of elderly in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina: population-based studyRev Bras Epidemiol2015181234247 English, Portuguese25651024

- DellarozaMSPimentaCAMatsuoTPrevalence and characterization of chronic pain among the elderly living in the communityCad Saude Publica20072351151116017486237

- McCarthyLHBigalMEKatzMDerbyCLiptonRBChronic pain and obesity in elderly people: results from the Einstein aging studyJ Am Geriatr Soc200957111511919054178

- DellarozaMSPimentaCADuarteYALebrãoMLChronic pain among elderly residents in São Paulo, Brazil: prevalence, characteristics, and association with functional capacity and mobility (SABE Study)Cad Saude Publica2013292325334 Portuguese23459818

- Mohamed ZakiLRHairiNNChronic pain and pattern of health care utilization among Malaysian elderly population: National Health and Morbidity Survey III (NHMS III, 2006)Maturitas201479443544125255974

- BarbosaMHBolinaAFTavaresJLCordeiroALLuizRBde OliveiraKFSociodemographic and health factors associated with chronic pain in institutionalized elderlyRev Lat Am Enfermagem201422610091016 English, Portuguese, Spanish25591097

- BauerHEmenyRTBaumertJLadwigKHResilience moderates the association between chronic pain and depressive symptoms in the elderlyEur J Pain20162081253126526914727

- LarssonCHanssonEESundquistKJakobssonUChronic pain in older adults: prevalence, incidence, and risk factorsScand J Rheumatol201619

- RoyRThomasMA survey of chronic pain in an elderly populationCan Fam Physician19863251351621267146

- ZanocchiMMaeroBNicolaEChronic pain in a sample of nursing home residents: prevalence, characteristics, influence on quality of life (QoL)Arch Gerontol Geriatr200847112112818006088

- RoyRA psychosocial perspective on chronic pain and depression in the elderlySoc Work Health Care198612227363616890

- HerrKAMobilyPRChronic pain and depressionJ Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv1992309712

- KlingerLSpauldingSJPolatajkoHJMacKinnonJRMillerLChronic pain in the elderly: occupational adaptation as a means of coping with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or kneeClin J Pain199915427528310617255

- TsaiPFTakSMooreCPalenciaITesting a theory of chronic painJ Adv Nurs200343215816912834374

- MosseyJMGallagherRMThe longitudinal occurrence and impact of comorbid chronic pain and chronic depression over two years in continuing care retirement community residentsPain Med20045433534815563319

- TurkDCOkifujiAScharffLChronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohortsPain1995611931017644253

- SchererMHansenHGensichenJAssociation between multi-morbidity patterns and chronic pain in elderly primary care patients: a cross-sectional observational studyBMC Fam Pract2016176827267905

- OladejiBDMakanjuolaVAEsanOBGurejeOChronic pain conditions and depression in the Ibadan Study of AgeingInt Psychogeriatr201123692392921241528

- DiatchenkoLNackleyAGTchivilevaIEShabalinaSAMaixnerWGenetic architecture of human pain perceptionTrends Genet2007231260561318023497

- PallerCJCampbellCMEdwardsRRDobsASSex-based differences in pain perception and treatmentPain Med200910228929919207233

- WiechKPlonerMTraceyINeurocognitive aspects of pain perceptionTrends Cogn Sci200812830631318606561

- DickensCMcGowanLDaleSImpact of depression on experimental pain perception: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysisPsychosom Med200365336937512764209

- BärKJBrehmSBoettgerMKBoettgerSWagnerGSauerHPain perception in major depression depends on pain modalityPain20051171–29710316061323

- KlauenbergSMaierCAssionHJDepression and changed pain perception: hints for a central disinhibition mechanismPain2008140233234318926637

- ThompsonTCorrellCUGallopKVancampfortDStubbsBIs pain perception altered in people with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental pain researchJ Pain201617121257127227589910

- CarsonMJDooseJMMelchiorBSchmidCDPloixCCCNS immune privilege: hiding in plain sightImmunol Rev2006213486516972896

- LymanMLloydDGJiXVizcaychipiMPMaDNeuroinflammation: the role and consequencesNeurosci Res20147911224144733

- RogersJMastroeniDLeonardBJoyceJGroverANeuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: are microglia pathogenic in either disorder?Int Rev Neurobiol20078223524617678964

- PaladiniAFuscoMCoaccioliSSkaperSDVarrassiGChronic pain in the elderly: the case for new therapeutic strategiesPain Physician2015185E863E87626431140

- HenekaMTCarsonMJEl KhouryJNeuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s diseaseLancet Neurol201514438840525792098

- PaladiniAMarinangeliFCoaccioliSFuscoMPiroliAGiustinoVNew perspectives in chronic and neuropathic pain in older populationSOJ Anesthesiol Pain Manag20152313

- CunninghamCMicroglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammationGlia2013611719022674585

- SkaperSDFacciLGiustiPMast cells, glia and neuroinflammation: partners in crime?Immunology2014141331432724032675

- LoggiaMLChondeDBAkejuOEvidence for brain glial activation in chronic pain patientsBrain2015138Pt 360461525582579

- WalkerAKKavelaarsAHeijnenCJDantzerRNeuroinflammation and comorbidity of pain and depressionPharmacol Rev20136618010124335193

- HongHKimBSImHIPathophysiological role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disordersInt Neurourol J201620Suppl 1S2S727230456

- RéusGZFriesGRStertzLThe role of inflammation and microglial activation in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disordersNeuroscience201530014115425981208

- BritesDFernandesANeuroinflammation and depression: microglia activation, extracellular microvesicles and microRNA DysregulationFront Cell Neurosci2015947626733805

- CarleyJAKarpJFGentiliADeconstructing chronic low back pain in the older adult: step by step evidence and expert-based recommendations for evaluation and treatment: part IV: depressionPain Med201516112098210826539754

- BarryLCGuoZKernsRDDuongBDReidMCFunctional self-efficacy and pain-related disability among older veterans with chronic pain in a primary care settingPain20031041–213113712855322

- RoweJWKahnRLSuccessful agingAging Clin Exp Res1998102142144

- SchreiberSVinokurSShavelzonVPickCGZahaviEShirYA randomized trial of fluoxetine versus amitriptyline in musculo-skeletal painIsr J Psychiatry Relat Sci2001382889411475920

- CiaramellaAGrossoSPoliPFluoxetine versus fluvoxamine for treatment of chronic painMinerva Anestesiol2000661–25561 Italian10736983

- AragonaMBancheriLPerinelliDRandomized double-blind comparison of serotonergic (Citalopram) versus noradrenergic (Reboxetine) reuptake inhibitors in outpatients with somatoform, DSM-IV-TR pain disorderEur J Pain200591333815629872

- ShimodozonoMKawahiraKKamishitaTOgataATohgoSTanakaNReduction of central poststroke pain with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamineInt J Neurosci2002112101173118112587520

- LeeRAWestRMWilsonJDThe response to sertraline in men with chronic pelvic pain syndromeSex Transm Infect200581214714915800093

- RaskinJWiltseCGSiegalAEfficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialAm J Psychiatry2007164690090917541049

- HossainSMHussainSMEkramARDuloxetine in painful diabetic neuropathy: a systematic reviewClin J Pain201632111005101026710221

- SmithHSSmithEJSmithBRDuloxetine in the management of chronic musculoskeletal painTher Clin Risk Manag2012826727722767991

- AiyerRBarkinRLBhatiaATreatment of neuropathic pain with venlafaxine: a systematic reviewPain Med Epub20161111

- LelicDFischerIWOlesenAEVenlafaxine and oxycodone effects on human spinal and supraspinal pain processing: a randomized cross-over trialEur J Neurosci201644112966297427748551

- WrzosekAObaraIWordliczekJPrzewlockaBEfficacy of tramadol in combination with doxepin or venlafaxine in inhibition of nociceptive process in the rat model of neuropathic pain: an isobolographic analysisJ Physiol Pharmacol20096047178

- Cegielska-PerunKBujalska-ZadrożnyMMakulska-NowakHEModification of morphine analgesia by venlafaxine in diabetic neuropathic pain modelPharmacol Rep20126451267127523238483

- MagniGConlonPArsieDTricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of cancer pain: a reviewPharmacopsychiatry19872041601643303068

- KreisbergMKTricyclic antidepressants: analgesic effect and indications in orofacial painJ Craniomandib Disord1988241711773076592

- BrownRSBottomleyWKUtilization and mechanism of action of tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of chronic facial pain: a review of the literatureAnesth Prog19903752232292096745

- GodfreyRGA guide to the understanding and use of tricyclic antidepressants in the overall management of fibromyalgia and other chronic pain syndromesArch Intern Med199615610104710528638990

- PaneraiAEMonzaGMoviliaPBianchiMFrancucciBMTiengoMA randomized, within-patient, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial on the efficacy and tolerability of the tricyclic antidepressants chlorimipramine and nortriptyline in central painActa Neurol Scand199082134382239134

- LiuWQKanungoATothCEquivalency of tricyclic antidepressants in open-label neuropathic pain studyActa Neurol Scand2014129213214123937282

- ArnoldPVuadensPKuntzerTGobeletCDeriazOMirtazapine decreases the pain feeling in healthy participantsClin J Pain200824211611918209516

- TheobaldDEKirshKLHoltsclawEDonaghyKPassikSDAn open-label, crossover trial of mirtazapine (15 and 30 mg) in cancer patients with pain and other distressing symptomsJ Pain Symptom Manage200223544244712007762

- JesseCRWilhelmEANogueiraCWDepression-like behavior and mechanical allodynia are reduced by bis selenide treatment in mice with chronic constriction injury: a comparison with fluoxetine, amitriptyline, and bupropionPsychopharmacology (Berl)2010212451352220689938

- VentafriddaVBonezziCCaraceniAAntidepressants for cancer pain and other painful syndromes with deafferentation component: comparison of amitriptyline and trazodoneItal J Neurol Sci1987865795873323130

- CalandreEPMorillas-ArquesPMolina-BareaRRodriguez-LopezCMRico-VillademorosFTrazodone plus pregabalin combination in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a two-phase, 24-week, open-label uncontrolled studyBMC Musculoskelet Disord2011129521575194

- GoodkinKGullionCMAgrasWSA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of trazodone hydrochloride in chronic low back pain syndromeJ Clin Psychopharmacol19901042692782149565

- Tammiala-SalonenTForssellHTrazodone in burning mouth pain: a placebo-controlled, double-blind studyJ Orofac Pain1999132838810425979

- TortaRGMunariJSymptom cluster: depression and painSurg Oncol201019315515920106657

- KarlinBEBrownGKTrockelMCunningDZeissAMTaylorCBNational dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system: therapist and patient-level outcomesJ Consult Clin Psychol201280570771822823859

- GouldRLCoulsonMCHowardRJCognitive behavioral therapy for depression in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trialsJ Am Geriatr Soc201260101817183023003115

- LintonSJNordinEA 5-year follow-up evaluation of the health and economic consequences of an early cognitive behavioral intervention for back pain: a randomized, controlled trialSpine200631885385816622371

- GlombiewskiJAHartwich-TersekJRiefWTwo psychological interventions are effective in severely disabled, chronic back pain patients: a randomised controlled trialInt J Behav Med20101729710719967572

- WilliamsACEcclestonCMorleySPsychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev201211CD00740723152245

- ButlerACChapmanJEFormanEMBeckATThe empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analysesClin Psychol Rev2006261173116199119

- ProudfootJClarkeJBirchMRImpact of a mobile phone and web program on symptom and functional outcomes for people with mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: a randomised controlled trialBMC Psychiatry20131331224237617

- MaceaDDGajosKDaglia CalilYAFregniFThe efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Pain2010111091792920650691

- KernsRSellingerJGoodinBRPsychological treatment of chronic painAnnu Rev Clin Psychol2011741143421128783

- McCrackenLMLearning to live with the pain: acceptance of pain predicts adjustment in persons with chronic painPain199874121279514556

- BoveroATortaRFerreroAA new approach on oncological pain in depressed patients: data from a clinical study using Brief Adlerian Psychodynamic PsychotherapyPsychooncology200615S1e478

- MacPhersonHVickersABlandMAcupuncture for chronic pain and depression in primary care: a programme of researchSouthampton, UKNIHR Journals Library2017 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK409491/Accessed March 30, 2017

- HoptonAMacphersonHKedingAMorleySAcupuncture, counselling or usual care for depression and comorbid pain: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trialBMJ Open201445e004964

- ElkinsGJensenMPPattersonDRHypnotherapy for the management of chronic painInt J Clin Exp Hypn200755327528717558718

- BrosseALSheetsESLettHSBlumenthalJAExercise and the treatment of clinical depression in adultsSports Med2002321274176012238939

- BairdCLSandsLA pilot study of the effectiveness of guided imagery with progressive muscle relaxation to reduce chronic pain and mobility difficulties of osteoarthritisPain Manag Nurs2004539710415359221

- FuscoMPaladiniASkaperSDVarrassiGChronic and neuropathic pain syndrome in the elderly: Pathophysiological basis and perspectives for a rational therapyPain Nursing Magazine2014394104